1. Introduction

The structure of competition wheelchairs for ball games, such as tennis, basketball, and rugby, is different from standard wheelchairs due to their use for wheelchair competition. Competition wheelchairs are required to have various functions, such as quick turn, sudden start, sudden braking, and high-speed driving. In wheelchair competitions, such as wheelchair rugby (WR), the wheelchair is required to have operability to avoid collision as well as durability for impacts.

A previous study which examined wheelchair athletes found them to have a high rate of injury to the shoulder, elbow, and wrist [

1]. Furthermore, a study which examined athletes’ muscle strength and shoulder pain revealed that the relationship between muscle weakness and shoulder pain was due to atrophy of the muscles around the shoulder blades [

2]. In these studies, one of the proposed causes was that suitable wheelchairs for the athletes’ physical characteristics may not have been used. There is currently no standard that reflects the physical characteristics, such as height, skeleton, and degree of disability, of athletes for the structure of the wheelchair despite the existence of safety standards for the wheelchair [

3].

Therefore, if it would be possible to evaluate competition wheelchairs by taking into account the physical load of the athlete, finding a suitable wheelchair for the athlete individually may lead to the reduction of injury risk and improvement of the performance. In our previous study [

4], although the muscle activity during the forward linear operation was estimated using the musculoskeletal simulation, the wheelchair operation was expressed not by the real measured motion but by the virtual motion. In addition, the relationship between the physical load and the operability could not be discussed in detail due to a lack of sufficient accuracy validation of the simulation results as well as the virtual motion.

Studies focusing on an evaluation of operability for robot arm manipulators were conducted using the manipulability [

5,

6]. As an example applying evaluation of the manipulability of robot arm manipulators to the human body, there have been some studies on the evaluation of the manipulability of the upper limbs in the operation space while sitting in the wheelchair [

7], the development of the method for prediction of the manipulability of the upper limbs for improving the operability [

8], and the design of vehicle shift’s characteristics based on the mechanical properties of the upper limbs [

9]. This research shows that the evaluation of the operability of robot arm manipulators can be applicable to an evaluation of the operability of the motion of the human body, and in particular, the upper limbs.

It is, therefore, desirable to understand the relationship between the physical load and the manipulability for evaluating the motion of wheelchair operation and selecting a suitable wheelchair for each user. In this study, hand manipulability was defined by adapting the evaluation of the manipulability. From the relationship between the hand manipulability and design parameters, this study investigated effects of the posture of the upper limbs during wheelchair operation.

2. Method

2.1. An Overview of Musculoskeletal Simulation

In this study, Anybody Modeling System (Anybody Technology Inc., Aalborg, Denmark, Anybody) was used for the musculoskeletal simulation based on inverse dynamics. In Anybody, a musculoskeletal model is constructed by inputting body parameters, such as height and weight, of a target human body. The body model, which consists of rigid segments (bones), junctions (joints) between segments, and muscle tendons composed of physiological specificity, is constructed based on human anatomy. The muscles of the musculoskeletal model have redundancy of joint degrees of freedom. Therefore, in Anybody, the muscular force of each muscle is estimated so as to minimize an objective function which is represented by the cube of the ratio of muscle force to maximum muscle force.

2.2. Construction of Body Model

The body model was constructed by scaling the body size and reducing the muscle strength from the standard model, which was installed in Anybody, based on the height and weight, and the disability of the subject, respectively. The degree of disability was represented by setting a decreased muscular strength to the target muscle part.

Classes in WR are set at seven levels (0.5 increments) from 0.5 to 3.5 based on the degree of disability [

10]. This score is set from the sum of scores based on degrees of the disability of the upper limbs and trunk. Therefore, even if the class is the same, the degree of disability of the upper limbs and trunk is different. The body model was aimed at the greatest number of players, which were categorized in class 2.0, with the upper limbs and trunk allocation of 2.0 and 0.0, respectively. As shown in

Table 1, the muscle strength of each part is set as a percentage of healthy subjects according to the class of the disability. The reason is that our previous study identified the trend that the triceps muscle plays a role in maintaining posture in addition to propulsion when the trunk muscle strength is lower [

4].

2.3. Construction of Wheelchair Model

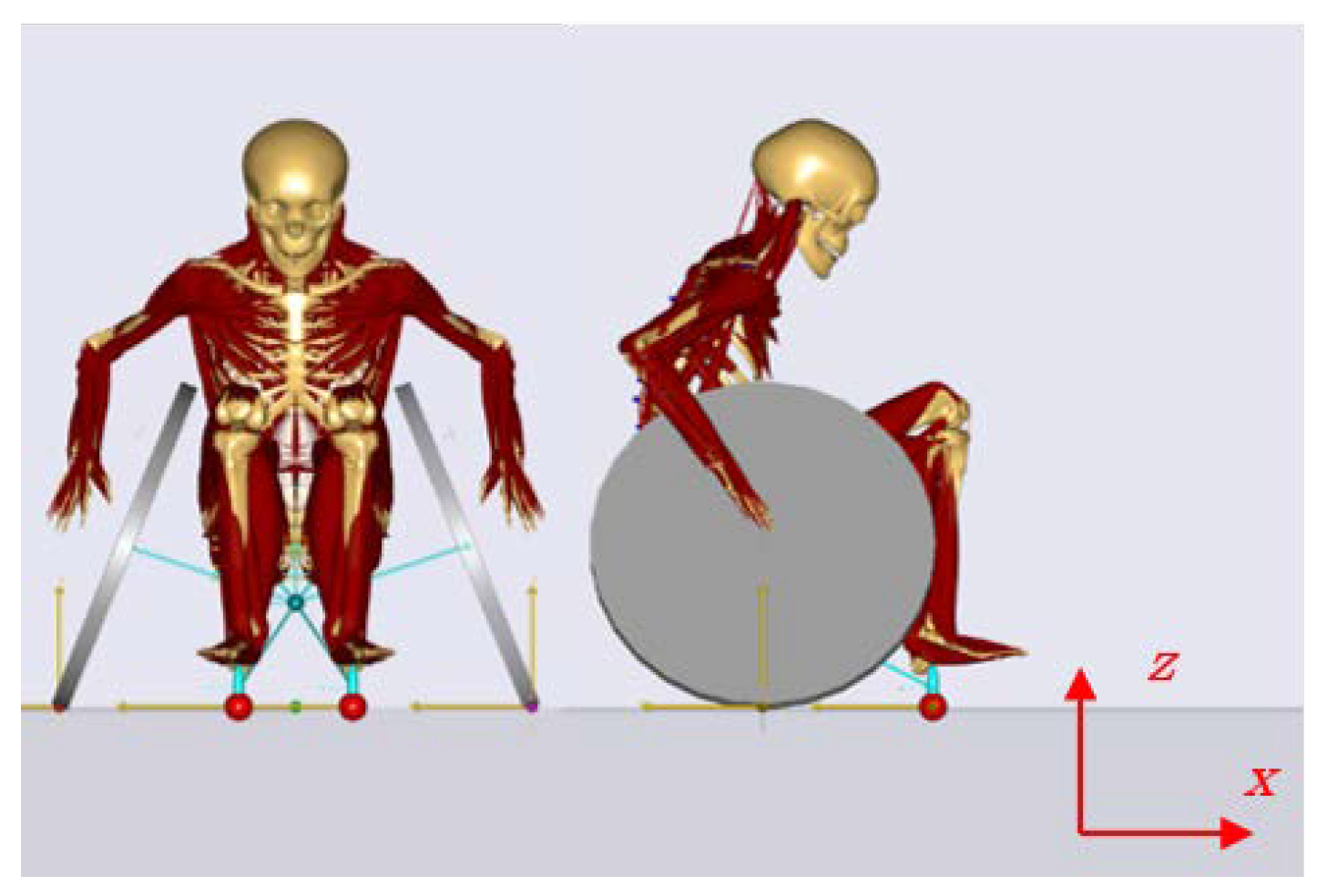

Figure 1 shows the construction of a competition wheelchair.

Table 2 shows the design parameters of the wheelchair. The wheelchair model was based on the wheelchair used in the measurement. The axle position was located at 40 mm forward and 50 mm upward from the center of the seat. In addition, the structure unique to the wheelchair for competition was not expressed in the model. The simulation was conducted with changes in the height of axle position from the standard at 50 mm intervals.

2.4. Measurement by Subject

In order to obtain the motion data necessary for the analysis, the 3D motion of the WR wheelchair was measured by a subject. The measurement was conducted using an optical motion capture system (MAC3D System, manufactured by Motion Analysis, MoCap). Twelve cameras (Kestrel 2200) were used for measurement at a sampling frequency of 100 Hz.

The subject was a male classified into class 2.0. The subject received an explanation about the experimental contents, and the measurements were taken after obtaining his consent. The implementation of this measurement had approval from the research ethics committee in our university. Reflective markers were attached on 36 locations throughout the body in accordance with Plug-in-Gait to measure the movement of the subject. In addition, in order to measure the movement of the wheelchair, markers were attached on four locations on the left and right with the axle and the wheel. The body’s markers were measured using capture suit with markers. The lower half of the body, which was hidden in the seat and frame of the wheelchair, was not tracked by MoCap.

The torque response around the axle of the right wheel was simultaneously measured using a strain gauge torque transducer (sampling frequency: 100 Hz) to validate the accuracy of the model.

2.5. Expression of Wheelchair Forward Linear Operation

A simulation model was constructed where the body model was seated on the constructed wheelchair model. The wheelchair model was given a forward linear operation and rotational motion of the wheel. The motion of the body was represented by introducing the time histories of joint angles of the shoulder, elbow, and wrist obtained based on the positional data of each marker into the body model. The time histories were approximated using a periodic function. The history data were inputted to the shoulder joint with 3 degrees of freedom (DOF), elbow joint with 2 DOF, and wrist joint with 2 DOF. The restraint between the body and the wheelchair was expressed by connecting the pelvis and seat, as well as the foot sole and footrest. The reaction force was estimated using a force element, which was constructed to the restraint part, and by conducting the optimized calculation at each force element so as to minimize the cube of the ratio of the reaction force to the maximum reaction force which was set for each force element in advance.

5. Conclusions

In this study, in order to investigate the evaluation of operability for a competition wheelchair using manipulability, the manipulating force ellipsoid and the hand force were estimated during the wheelchair operation using musculoskeletal simulation. Hand manipulability was defined as the angles between its vector and the vector of hand force estimated from the simulation. The effects of the design parameter for the wheelchair on manipulability were investigated by conducting simulations with changes in axle positions. As a result, the following conclusions were found:

Changes in the contact point between the hand and the wheel with changes in axle positions have an effect on the hand manipulability α.

Setting a higher axle position may lead to an increase in energy efficiency of the wheelchair operation.

Setting a lower axle position may lead to a reduction in the physical load.

In conclusion, the present study has demonstrated that it is possible to evaluate an optimum structure for a competition wheelchair by investigating the relationship between hand manipulability α and design parameters. It is suggested that an optimum contact point between the hand and the wheel could lead to increased energy efficiency and reduce the physical load on the wheelchair operation.