3.1. Production Process of Slides de Cavalete

On the first page of the file recording the production process of the work Slides de cavalete, dated from 1988 and signed, the artist briefly describes the process and the materials he used. He also explains that preliminary tests were necessary to master issues of filtering, exposure times, film characteristics, etc. In the same file, more information could be found, such as: (i) typed texts (that appear at the beginning and at the end of the work); (ii) hypotheses for the script (not the final script); (iii) information about the conducted tests (carried out between 11th February and 4th March 1979) and some examples of the resulting slides; (iv) schemes and notes mentioning the equipment needed to produce the slides and their precise positions; (v) shape proportion; and (vi) sketches explaining how to obtain the desired luminous gradations. Based on this documentation, it can be concluded that Slides de cavalete resulted from extensive planning and experimentation. In the turn of the 1970s, Ângelo de Sousa would have to wait several days or weeks for the film to be processed abroad before assessing the obtained results. The images were therefore only existent in his head and sketches. This idea was made clear in the title resorted by the artist for the first presentation of the artwork, previously mentioned. Considering the test slides that remain in his archive (about 260 slides), it is also possible to conclude that other compositions were tested, with different shapes and contrasts. Thus, the slideshow would have been the outcome of a selection of images chosen from the obtained results.

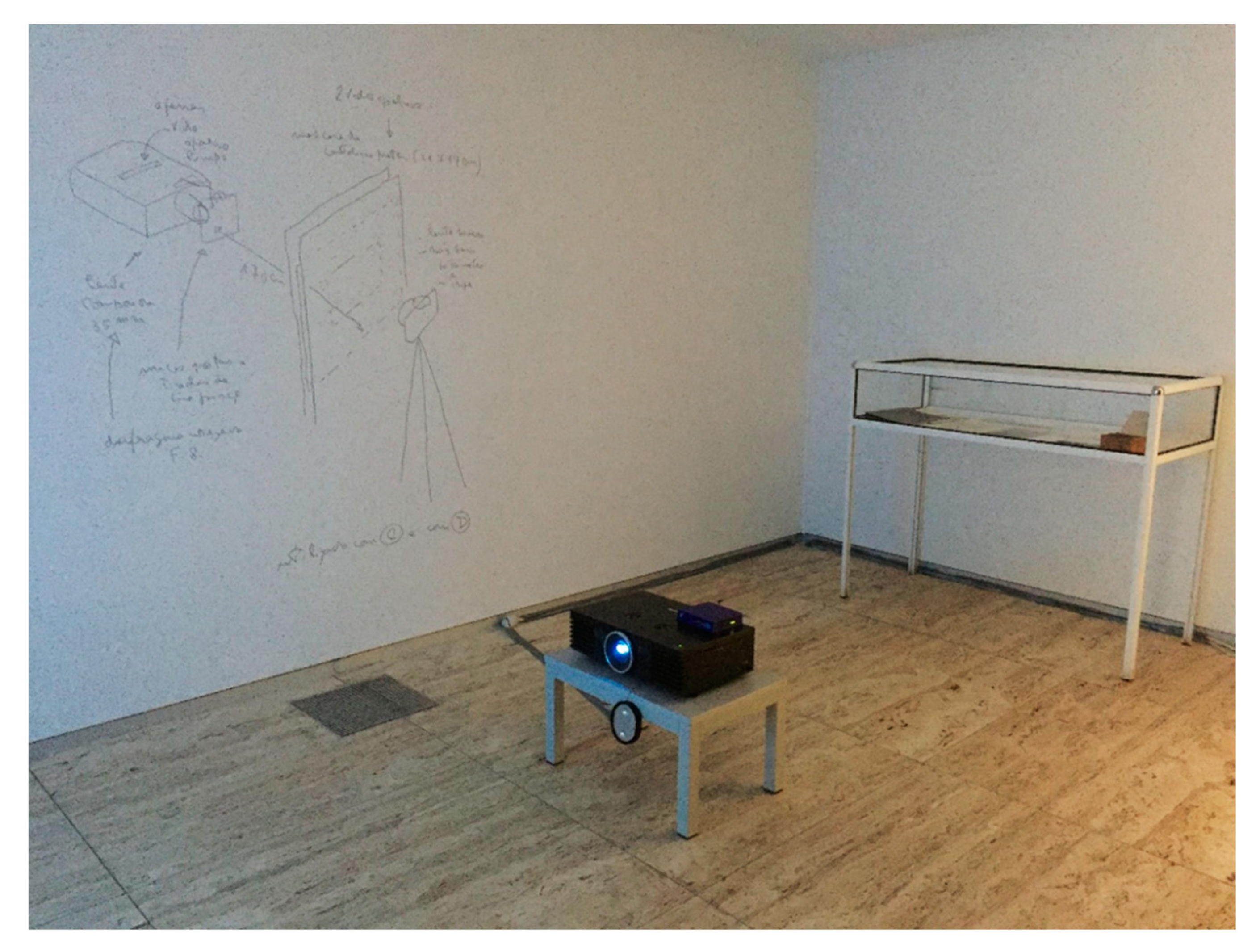

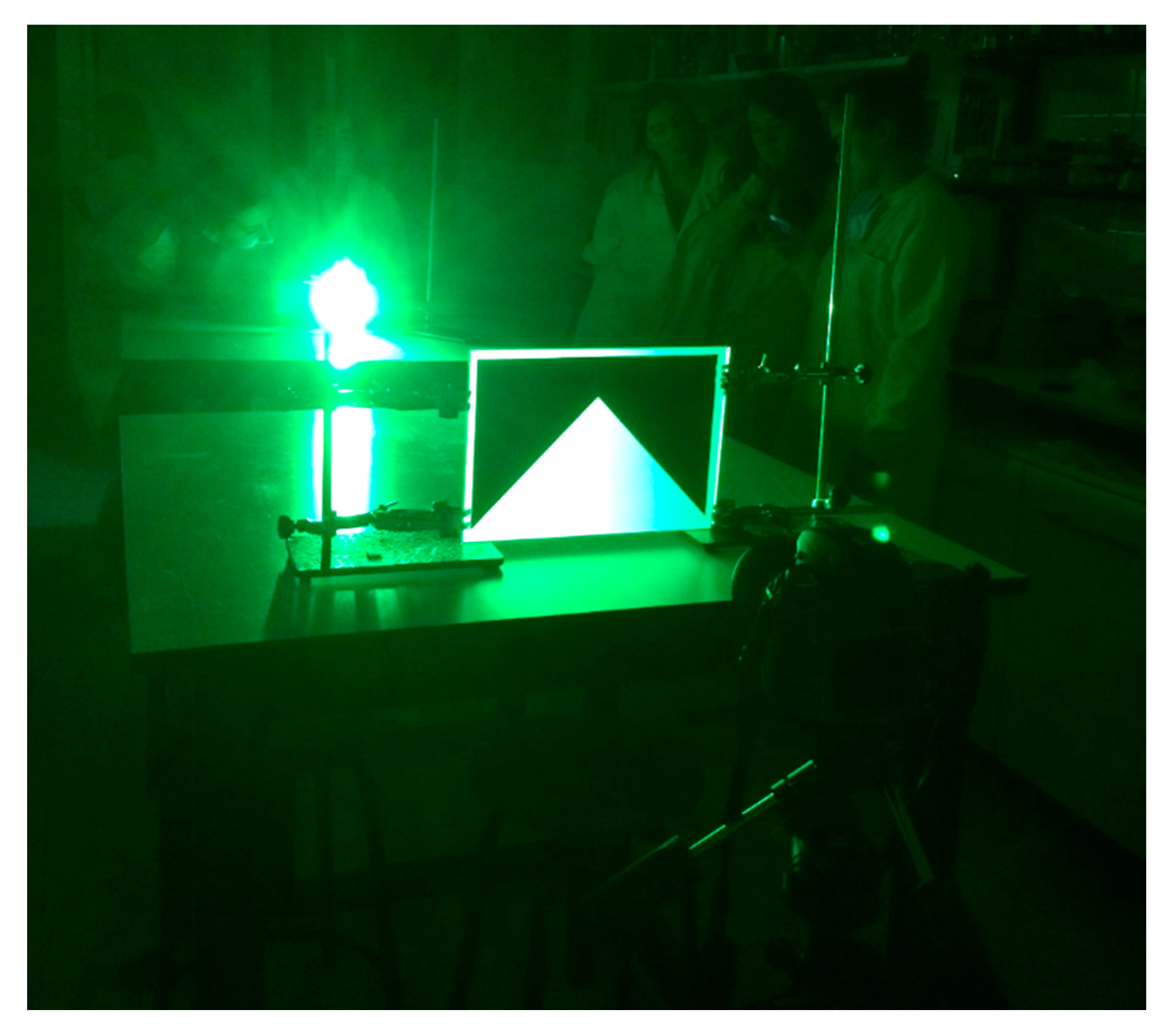

After analysing the documentation and materials left by the Ângelo de Sousa, the reproduction of the production process was carried out to achieve an understanding of the artwork as complete as possible. Although the layout of the equipment was arranged according to the documentation left by the artist, some adaptations had to be done due to the specificities of the apparatuses and materials at use (distance between equipment, exposure times, lens aperture, etc.), which were different from those used by the artist (

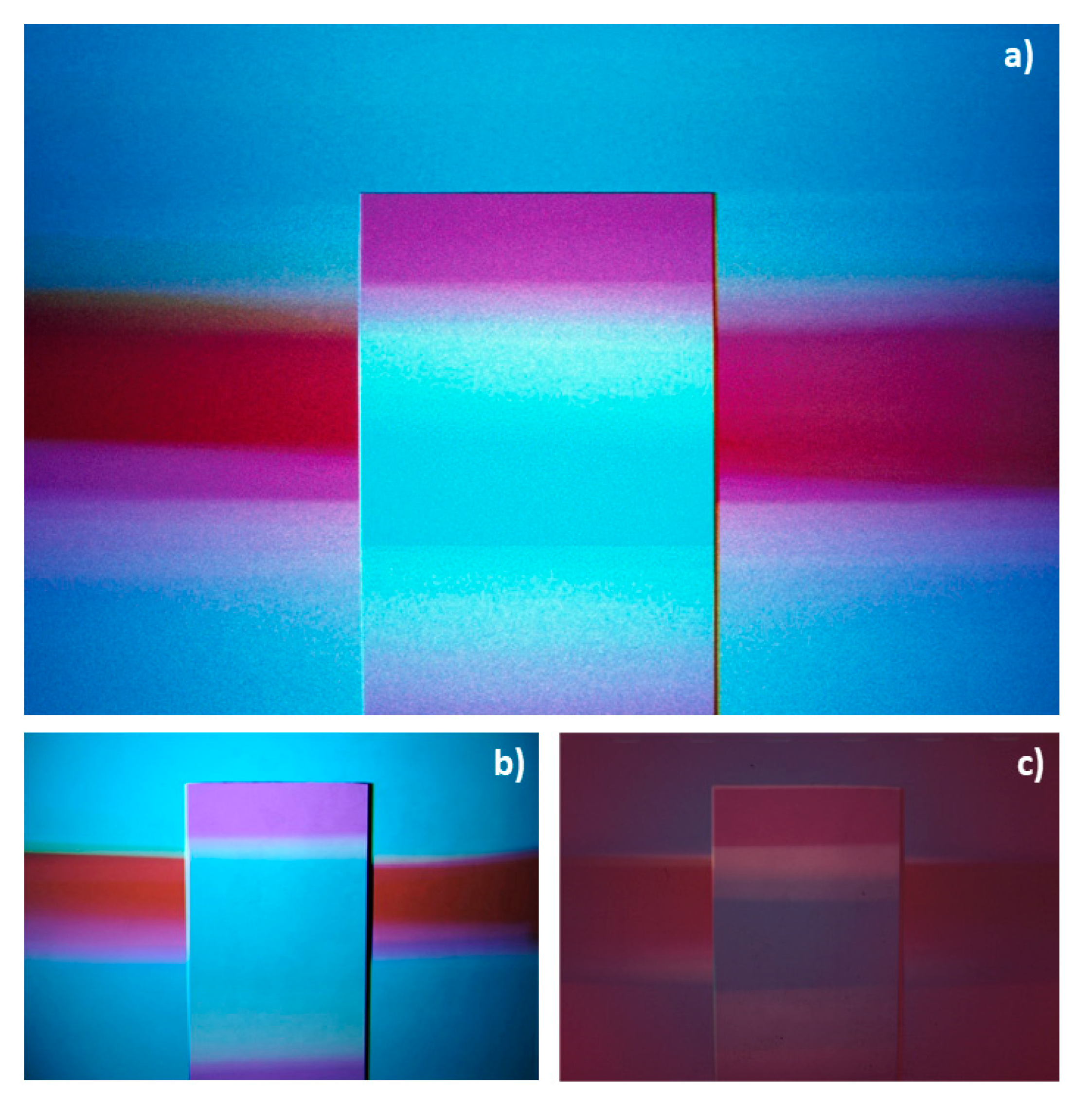

Figure 5). The obtained reproductions for slide 58 (both digital and analogue) can be seen in

Figure 6. The first tests were carried out by using a digital camera (multiple-exposure mode), to immediately assess the obtained results. Interestingly, in the documentation left by the artist, he refers that: “by using other resources-electronic, a computer-I could have obtained results, not only faster, but also with other ambitions with regard to the details′ treatment.” After mastering the technique, the process was repeated with an analogue photographic camera. However, the results obtained with this camera were not so satisfactory since the images were obscured. This may be due to technical problems related to the photographic camera (exposure time) or to the chromogenic reversal film (inadequate film type, incorrect development, etc.).

Nevertheless, this practical experiment was very helpful in recognizing certain subtleties required while obtaining colour gradations, which were not explicit in the documentation left by the artist. The reproductions also enabled to understand the complexity of the images composing the work, both in terms of its concept and execution process. It should be emphasised that, contrarily to Ângelo de Sousa who worked alone (as far as it is known), the reproduced images were obtained with the participation of several students managing the different tasks implied in the process (shooting, changing filters, changing masks, applying secondary masks to produce light gradations, etc.).

Based on the research that has been conducted, it is now possible to come forward with a proposition on how the work

Slides de cavalete was produced, described below, and outlined in

Figure 7:

A slide projector was used to project R, G, and B lights, on two frosted glass panes (on a roughly A4 format). To do so, filters with these colours, as primary as possible, were placed inside slide mountings, and projected, one at a time, during the exposure;

Filters (e.g., frosted glass with and/or without painted grids) were used to reduce the amount of light reaching the glass panes, and make it possible to increase the exposure time;

Cardboard masks (triangular or rectangular) were fixed between the glass panes to alternately block the light in the shape or in the background and expose the two areas, separately;

Secondary masks were used to block the light in selected areas and to obtain colour gradations, usually very subtle, as if applying the technique of “sfumato.” These could be opaque objects such as hands or cardboards, slowly moving in front of the lights during the exposure time;

A photographic camera was placed at a certain distance behind the glass to successively capture multiple exposures of the R, G, and B lights. Three exposures for the shape and three for the background are needed. Coloured lights were captured on chromogenic reversal film, each frame/slide being composed of six exposures.

For example, by successively projecting each coloured light for the same proportion of time, through multiple exposures in the same frame, the pure white colour could be obtained. If the artist played with different proportions of the three filters, which he controlled by using opaque secondary masks to reduce light exposure in certain areas, he would obtain different tones and gradations. By complying to the principle of additive mixing, and according to his own words, he would be able to predict the result of the sum of the primary colours [

20]. The production process was described by him as very simple and quite predictable, but with a certain degree of randomness, which he also controlled through experimentation. In our experiments, the colour gradations were obtained by moving cardboards, in front of the glass panes during the exposure time, usually very slowly.

Figure 8 shows the secondary masks used for each one of the coloured filters (RGB) for the background and shape to obtain the colour gradations and reproduce the selected slide.

It should be highlighted that, besides being an important piece for the display of the artwork, the slide projector was essential for its production.

3.2. Display Testing at FCT NOVA

The two scenarios of this exhibition were supposed to be built with the exact same characteristics. However, some technical constraints have arisen during the process of installing the exhibition, making this goal difficult to achieve. Nevertheless, the variations described below were considered not to affect the results of the study.

According to an investigation conducted by Haida Liang, Pip Laurenson, and David Saunders [

24], in a partnership between the Tate and the National Gallery (London, UK), digital duplication of slide-based artworks has led to accurate copies. As stated by Tina Weidner [

25], this solution allows for the maintenance of the original physical support and it can be considered a good alternative to analogue duplication. Unfortunately, the obtained colours of the exhibition set were not very accurate: the copies presented less vivid and darker colours than the original artwork. Due to a lack of resources and time, these slides were presented at the exhibition. Contrarily to what might be supposed, colour accuracy was not easier to achieve with the digital projection; it was difficult to obtain a good reproduction of all the colours in the same image within the several modes and adjustments tested. If good profiling and light intensity adjustments would have been assigned to the projector, a better dynamic range and rendering of colours would have probably been achieved. However, no technicians with this type of knowledge were available. Since the carousel of the projector could only hold eighty slides, a selection of the slides to be projected had to be made (Removed slides: 5, 8, 14, 17, 19, 32, 36, 40, 41, 46, 51, 53, 57, 59, 64, 69, 76, 91, 93, and 95). Although the artwork should be presented in a suitable carousel, as it was unavailable and deemed not to affect the result of the experiment, the work was presented in the above-mentioned way. The images were selected as to maintain the proportion of images with triangular and rectangular shapes and the representativeness of the images to be presented. The latter was quite difficult to achieve, especially for the second part of the work, since the images with rectangles have a higher chromatic complexity, and therefore, a higher variability from image to image. The global work could have been projected with the digital projector; however, it was decided to present the same images in both projections to avoid undesirable differences in the two scenarios of experimentation.

Additionally, according to the projector at use, different stands had to be employed. In scenario A, the digital projector was placed over a small grey table, and in scenario B, the slide projector was set over a white plinth.

The difficulties encountered during the preparation of this experimental study illustrates the kind of issues faced by institutions when exhibiting slide-based artworks, due to the obsolescence of the image carriers and display equipment.

The target population of this experimental study was the public at large. However, an intentional sampling was collected by personally inviting some individuals, such as professionals from the conservation field outside of the academic world, as well as university professors and colleagues. This sampling was intended to put together a group of people who was familiar with art and frequently visit exhibitions, being particularly able to respond to the present investigation. Nevertheless, there was no intention of analysing differences in responses by area of training or level of education. In addition, first year Master students from the Department of Conservation and Restoration (DCR) were formally invited to participate in the study, as part of their academic training. At the end, the sample consisted of thirty-nine persons (number of persons who observed the two scenarios of presentation and filled out the questionnaire), twenty-five of which participated in the workshop. The total number of visitors is unknown.

The characterization of the interviewees is presented in

Figure 9. Most people who participated in the study are Portuguese. The age of the respondents ranged from 21 and 70 years (average: 34). The great majority are from the conservation and restoration field, either conservators or (mainly) students. Since the conservation and restoration degree is, statistically speaking, predominantly attended by female students, these were the majority amongst the respondents.

The respondents are people who often visit exhibitions, as expected. All questionnaires were filled in by persons with a higher education diploma.

An attempt to correlate the characterization of the respondents with the obtained results was made. However, no statistically relevant relationships could be established. The results obtained by comparing the two scenarios of experimentation against the evaluation criteria (i) image quality and beauty, and (ii) global scenario/installation, are summarized in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. When comparing the two scenarios of experimentation, within the various parameters, a significant difference emerge by applying a nonparametric test for matched or paired data, the Wilcoxon signed rank test (

p < 0.001) [

26]. Overall, the respondents had a better appreciation of the experience of the artwork presented with the slide projector than with the digital projector.

Regarding the image quality and beauty, most respondents classified the several variables of the digital projection as having good quality, with the slide projection as having excellent quality. Regarding the slide projection, the variable “colour beauty” can be highlighted, having 84.6% of the respondents classifying it as having excellent quality. The “colour brightness” had the worst classification among the slide projection, with only 51.3% of the respondents considering it as having excellent quality. Nevertheless, this variable had a far better classification than it had with the digital projection. In general, the evaluation of the digital projection is more distributed amongst all variables (values spread between excellent and mean quality), than it is for the slide projection. Regarding the global scenario/installation, the same trend was observed in a more discernible way. In the slide projection, all variables were classified above 70% as having excellent ambience. Thus, there was a very clear positive appreciation of the global scenario/installation for the slide projection. In the classification of the digital projection, the opposite emerges. The evaluation is distributed between excellent and bad ambience. The variable “harmony between work and projection” in the slide projection should be highlighted since 94.6% of the respondents classified it as having excellent ambience. This classification shows a high contrast with the classification of the same variable in the digital projection, in which only 23.1% of the respondents considered it as having excellent ambience and 10.3% considered it as having a bad ambience. Regarding the variable “sound of the projection,” 28.6% of the respondents considered that in the digital projection there was a bad ambience, whereas in the slide projection 78.4% considered that there was an excellent ambience. Nevertheless, this variable was quite ambiguous for a certain number of people, since the sound was absent in the digital projection. This fact is reflected in the percentage of respondents that did not classify this variable (10.3% missing). Similarly, it can be concluded that certain people also had difficulty in classifying the variable “beauty of the projection,” since 5.1% of the sample did not respond.

The impact of the attendance of the workshop in the perception of the artwork was studied by applying a nonparametric test used to compare two samples and detect non-normality, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, to each presentation scenario and evaluation parameter [

26]. In general, it can be stated that the attendance of the workshop had no statistical relevance in how respondents evaluated the various parameters. This finding might indicate that, independently of the visitors being informed about the production process of the artwork, they still prefer it presented with the slide projector.

It is important to emphasize that the described information was obtained from questionnaires made to a very specific population. As previously mentioned, most of the people who visited the exhibition came from the conservation field. Normally, conservators are trained to observe and study the materiality of objects. Therefore, this characteristic almost certainly influenced their perception of the artwork under consideration. People from other fields, however, were also part of the population who answered the questionnaires and shared their experience of the work within the two scenarios. Moreover, according to the statistical treatments applied to the obtained data, no special trends could be established for the different professions or fields of expertise of the respondents.

In addition to the statistical treatment of the questionnaires, sixteen oral testimonies (41% of the respondents) were collected to enrich the obtained data. From these testimonies, eleven people clearly showed their preference for the slide projection, which is in line with the results obtained from the questionnaires. A few individuals claimed that the work does not make sense presented with the digital technology, especially if projected on a canvas over an easel. Some people also mentioned the importance of the slide projector as a testimony to the production process. Thus, the removal of the slide projector from the presentation of the artwork would mean the removal of a significant part of the work. Following the same idea, some people also mentioned the importance of the original technology in the historicity of the work. Additionally, some respondents raised the importance of the slide projector for the maintenance of the materiality of the work. A slide projection is a result of the passage of light through a chromogenic reversal film, which is matter, while a digital projection is based on the emission of light, which has a different appearance. One respondent also argued that the digital projector somehow removes the installation character of the artwork. Some people, however, considered that the use of a digital projector to present the artwork is an acceptable possibility. Some people, knowledgeable of Ângelo de Sousa’s work, claimed that the artist would have been amenable to the mutation of the work into a digital format. Regarding the perception of the image in both scenarios of experimentation, in a general way, people preferred the quality and beauty of the image projected with the slide projector. Three people noted that the most important aspect to consider in the evaluation of the artwork is the quality of the image. Several people mentioned, as positive outputs, that the slide projection produced an image with more granularity, with warmer hue, and was less flat and homogeneous when compared with the digital projection. Some people also highlighted the fact that a higher depth of the images was achieved with the slide projection (conferred by the darkness of the corners), an aspect lost in the digital projection. The sound of the projection was a variable often mentioned in the oral testimonies. Two respondents noted that the sound from the slide projector could be somehow disturbing, distracting the attention from the images themselves. In one testimony, it was noted that the absence of sound could lead to a sort of a sublime state during the observation of the sequence of the images. However, the majority of people considered the presence of the sound, so characteristic of the slide projector, as an important factor, by conferring a narrativity to the artwork and capturing the visitor’s attention. The rhythm of the slide projection, induced by the passage of the slides, was also mentioned as a positive outcome that would create the feeling of a sequence or a narrative. One respondent mentioned that the digital projection looked faster than the slide projection, possibly due to a more sudden transition between images.

Besides the oral testimonies, relevant information that arose from conversations between visitors during the exhibition time was collected. From this observation, it is worth mentioning that various students had never seen a slide projector before this exhibition. Some did not even understand, at first, if the artwork was being displayed with a digital or a slide projector. When some of the students saw the slide projector, they were very enthusiastic about it. This leads to the conclusion that the subtraction of the original technology might bring especially significant consequences for the future (and current) generations. Even if it is explicit to the public that the original technology consisted of projected slides, people who do not know what a slide projector is might not be able to understand what it entails since this technology is no longer part of our everyday lives.