Abstract

In the Roman Empire, lead tags were used for various purposes, one of which was to label textiles that needed cleaning, repairing or dyeing. So far, these tesserae have been found at over 90 sites in 13 Roman provinces. The cities of Siscia and Carnuntum in Pannonia Superior have the highest number of finds. In 2011, a Roman cesspit was excavated in the civil city of Carnuntum and dated to the mid-2nd century CE. The latrine contained household and food waste, human faeces, pottery shards, pollen, lime, amber and 179 lead tags. The tags bear inscriptions consisting of personal names, prices, and abbreviations of terms relating to garments, colours and services such as cleaning, mending, repairing, fulling, fumigating, perfuming, dyeing, and redyeing. The findings of Roman textiles unearthed in Carnuntum are too degraded to allow a successful dye analysis to be carried out. Therefore, the inscriptions are important sources for drawing conclusions about dyeing materials and techniques. This information was supplemented by ancient written sources as well as archaeobotanical finds of dye plants and dye analyses of archaeological textiles found in Central Europe dating from the same period or earlier.

1. Introduction

In the Roman Empire, commercial tags made of lead labelled trade products as well as personal belongings. These tags, also known as lead tesserae or lead labels, usually have a hole so that they can be attached to objects with a string or a metal wire. The systematic study of inscriptions is an important area of epigraphic research [,,,,,,,,]. Lead tesserae have been excavated in many Roman provinces [] (pp. 144–147), in the provinces of Britannia [,], Hispania Tarraconensis [,], Lusitania [], Gallia Belgica, Gallia Lugdunensis and Gallia Narbonensis [,,,,,,,,,,,], Germania Superior [,,,], Germania Inferior [], Raetia [,,], Italia [] (p. 122, footnote 8) [,,,,,,,,], Noricum [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,], Pannonia Inferior [,] and Pannonia Superior [,,,,,,,,,,]. Most of them date between the 1st and 3rd century CE []. To date, approximately 2,200 lead tags originating from the Roman provinces have been identified.

The majority of the labels originate from two Roman cities in Pannonia Superior. 1123 were found in Siscia (now Sisak, Croatia) and date to the 1st and early 2nd centuries CE, whereas 179 were found in Carnuntum (now Petronell-Carnuntum, Austria) and date to the mid-2nd century CE [,]. The labels from both archaeological sites suggest a local use in a textile workshop for services such as fulling, cleaning, repairing, fumigating, perfuming, dyeing and redyeing. The craftsmen attached the lead tags to the textiles to make them easily returnable to customers. These workshops are known from written sources for fulling (fullonicae), for dyeing (officinae infectoriae) and for redyeing of worn clothes (officinae offectoriae). Other tesserae used in textile production or dyeing are known from Gallia Narbonensis: Fréjus (France) [], Germania Superior: Vitudurum-Oberwinterthur (Switserland) [,], Raetia: Forggensee bei Dietringen (Germany) [], Italia: Feltria-Feltre (Italy) [], and Noricum (Austria): Aelium Cetium-St. Pölten [], Immurium-Moosham [], Magdalensberg [,] and Kalsdorf [,,,,]. K. Gostenčnik provides an overview of lead labels found in Austria and related to textile production [] (pp. 94–102).

2. Materials and Methods

In 2011, a Roman cesspit was excavated near Petronell Castle, which was built in the 17th century CE (Figure 1) [,].

Figure 1.

Profile of the Roman cesspit, located in Carnuntum near Petronell Castle, Photo: © B. Petznek, ARDIG—Archäologischer Dienst GesmbH.

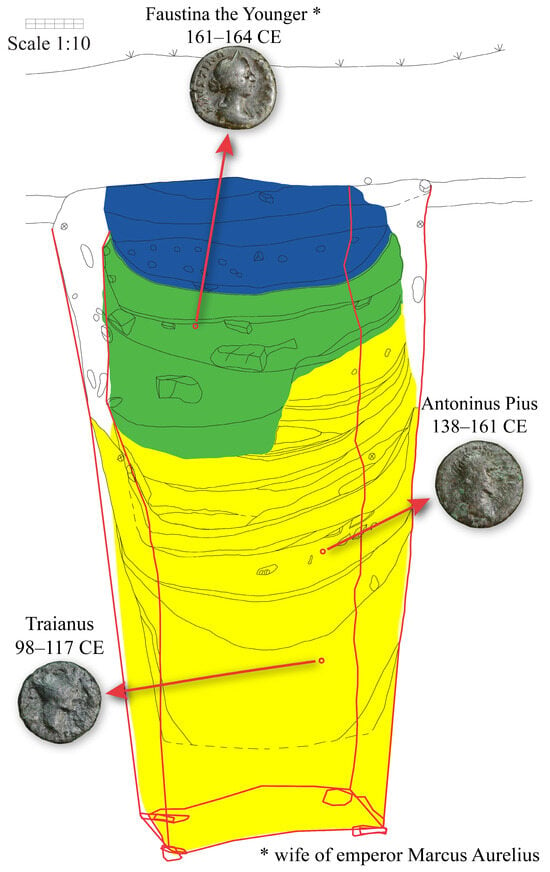

This site was part of the Roman civil town of Carnuntum, the provincial capital of Pannonia Superior with a population of around 50,000 inhabitants. Three coins fell into the latrine in Roman times: a dupondius of Trajan (minting phase II: 98–117 CE), a dupondius from the reign of Antoninus Pius (minting period: 138–161 CE) and an As showing Faustina the Younger, wife of Marcus Aurelius (minting period: 161–164 CE) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Layer plan of the Roman cesspit, supplemented by the information from numismatic dating. The lead tesserae originate from the yellow-coloured strata. Colour coding: yellow = primary backfill (phase I: up to mid-2nd century CE), green = secondary backfill (phase II: beginning with mid-2nd century CE), blue = final backfill (phase III: mid-3rd century CE). Profile drawing: B. Petznek [] (p. 123, modified).

Investigations into the finds from the latrine were carried out as part of numerous interdisciplinary research projects. The results will soon be published in a German anthology on the trade, economy, culture and natural environment in the Carnuntum Region during the Middle Imperial period. This will include the lead tags from Carnuntum (Petronell Castle) []. This article provides an overview of research into lead labels, with a focus on textile services, colours and dyeing. It also mentions analyses of coins conducted by U. Schachinger and isotope analyses of the lead carried out by R. Schwab and E. Pernicka [].

On the basis of the found coins, the cesspit is dated to the mid-2nd century CE. The date is supported by pottery shards from the first half of the 2nd century CE. In addition to the coins and pottery shards, the cesspit contained human faeces, disinfecting lime, parasites, pollen, animal and plant food waste, household waste and lost and discarded objects including a dice, bone needles, shoe nails, pearls, hair pins, amber and 256 lead finds. Archaeozoological, archaeobotanical, palynological, parasitological and chemical investigations have provided information about the flora and fauna, the state of health and the eating and living habits of the Carnuntum population in the 2nd century CE and the origin of the metal lead. The provenance of the metal lead was investigated using lead isotope analysis. It was found that the lead used for the Carnuntum tags originated from the silver-bearing lead mines of the Roman province of Moesia Superior, which is now part of Serbia.

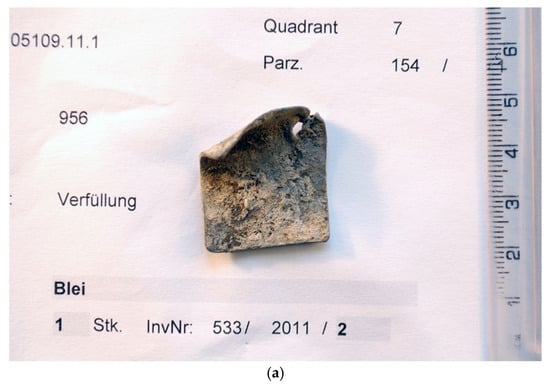

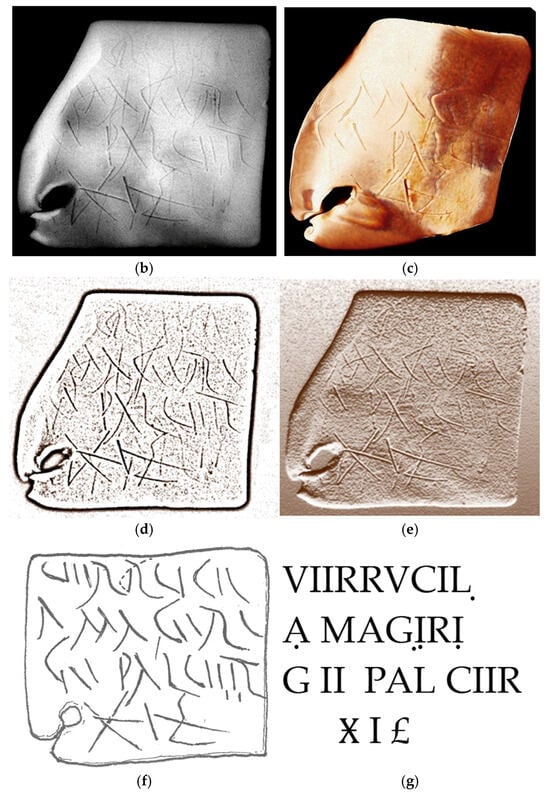

A total of 179 of these metal finds are lead tags with engraved inscriptions on one or both sides. The lead labels are rectangular to square, approximately 40 mm long and 35 mm wide, and most of them have a hole. The inscriptions, completely or partially preserved, consist of letters written in Old Roman cursive, 2–4 mm high, with many abbreviations. One of the properties of lead is its softness, which enables inscriptions to be easily engraved. Another advantage is that a lead label could be reused after heating and hammering. Due to the environment in the latrine, the labels were badly corroded and encrusted with sediment. After cleaning and restoring the objects, X-ray images and CT-scans enabled I. Radman-Livaja to draw, transcribe and interpret the inscriptions []. Lead tag FN533-211-02 illustrates the steps required to make the inscription legible (see Figure 3a–g). Further information about the inscription on this label can be found in Section 12.

Figure 3.

Lead tag FN533-2011-02 (a) non-restored. Photo: © M. Raab, ARDIG—Archäologischer Dienst GesmbH. (b) X-ray image. © M. Schäfer, University of Vienna, Department of Prehistoric and Historical Archaeology. (c) Computer tomography. © S. Handschuh, University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna. (d,e) X-ray images, post-processed with image editing software. Photos: © B. Petznek. (f,g) Drawing and reading. © M. Galić and I. Radman-Livaja.

The article focuses on terms related to fumigating, mending and perfuming, as well as colours and Roman textile dyeing (see Section 5, Section 6 and Section 7 and Section 9, Section 10, Section 11, Section 12, Section 13, Section 14, Section 15 and Section 16 below). Examples are provided, and the find number (FN) indicates the corresponding label.

The inscriptions on the Carnuntum labels were investigated based on bibliographical references [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,] as well as by consulting ancient written sources, reports about archaeological finds and publications about dye analyses of archaeological textiles (see Section 6 and Section 8).

3. Results and Discussion

Roman lead labels are important objects for epigraphic research, providing information about daily life in the Roman provinces. Despite being known and recognised from numerous Roman sites long before that, lead labels were the subject of systematic research for the first time in the 1950s and 1960s. The investigation into lead labels is a work in progress. Researchers are attempting to decipher the inscriptions of new excavated labels as well as those that still defy meaningful reading. They also sometimes offer new interpretations of previously researched labels. One example is a label from Trier. The term PIPIIR was originally interpreted as piper (pepper), from which it was concluded that the label was affixed to an object in which pepper was imported to Trier [] (pp. 36–37) [,] (pp. 123–129) [] (pp. 425, 433). Nowadays, experts tend to believe that the term means piperinus (pepper-coloured) and that it was once attached to a piece of fabric [] (p. 74) [] (pp. 289–293).

The more inscribed labels that are examined systematically, the greater the chance of deciphering inscriptions that have not yet been clearly understood. It would be interesting to find out if workshops in the Roman provinces used the same abbreviations.

Examining the terms and abbreviations on the Carnuntum lead labels drew on a wealth of experience. The palaeographic notes in the monograph on the tesserae from Siscia offer a comprehensive overview of the abbreviations appearing on the labels and their respective meanings [] (pp. 52–90). It is also an advantage, that the inscriptions always follow a specific sequence. First comes the name of a person, presumably a client, followed by the textile, usually a garment, the service, the colour and finally the price. Making matters worse, there is sometimes no entry in one of these categories. While only a few personal names are abbreviated, information on textiles, services and colours consists of just a few letters, or sometimes even a single letter. It is reasonable to assume that these abbreviations were clear and unambiguous to the people working with the textiles in Roman times. Therefore, an abbreviation should always have the same meaning. However, in some cases, research has not yet been able to determine the meaning of abbreviations. For example, an abbreviation that refers to a textile can have different meanings: PA can mean either palla (a cloak) or pannum (a cloth), and B can mean two different cloaks, a banata or birrus. There are even more abbreviations that have multiple meanings (see Section 5 and Section 7). However, different abbreviations were also used for the same term, which presumably did not cause any confusion in the workflow. For sulfure suffire (fumigate with sulphur), the abbreviations SULFUR, SULFU, SUL, SU and possibly also the letter S appear. It is also possible for an abbreviation to be interpreted as a colour adjective or dyeing process, or as another service. Various abbreviations were used for purple shades or for dyeing in purple shades, such as PURP, PUR and PU, as well as the letter P. Alternatively, PUR, PU and P could also mean purgare (to clean).

Despite the many uncertainties, an attempt was made to systematically record and graphically represent the terms (see Section 6 and Section 7). Abbreviations consisting of only one letter can be open to too much interpretation. For this reason, they have not been included in the graphs. However, even those consisting of multiple letters can refer to different terms. In the case of terms relating to colours and dyeing, some belonged to different colour categories. As the aim was to assign each term to a single category, the following solution was implemented. These abbreviations were assigned to the most likely meaning and counted in only one colour category. The other meanings are mentioned in Section 7. The results and discussions are continued in the following sections.

4. Clients and Prices

Personal names are present on at least 142 lead tags. They usually mention one person, but sometimes two or even three, who are considered to be clients. On two labels, the word fullo is written after the names Euchilus (FN438-2011-48) and Rest(it)utus (FN532-2011-02). This could mean that the service should be carried out by the fullo, the fuller, in the workshop. It is also possible that this individual’s profession is simply a descriptive detail used to distinguish them from other clients with the same name. This could be true for Rest(it)utus, a name that is very common in Pannonia. Conversely, it is unclear why the profession of Euchilus should have been emphasised to avoid potential confusion. This name appears to have been used very rarely. It seems to be a Hapax legomenon.

The gender and origin of the names can be deduced from personal names. Customers are categorised into four groups based on their individual names []: 45 people are Roman citizens, 38 men and 7 women. They usually have a nomen gentile (family or clan name) and a cognomen (third name), but they occasionally appear bearing a praenomen (first name) and a nomen gentile, and only seldom bearing tria nomina, i.e., all three names. A total of 49 people, including 29 men and 20 women, belong to the so-called peregrini. These are free people but without Roman citizenship. Their name (idiom) is followed by a patronym. A total of 48 individuals, 35 men and 13 women, have only a single name. It is unclear whether they were peregrini, Roman citizens or slaves. 56 names have been partially preserved, giving hardly any information about their gender, status or origin. This article mentions names of the Roman citizens Albanius Marcus, Ulpius Bato, Valerius Porilus and Iustia Saturnina, names of the peregrini Adnuo? Maturi, Fortis Terti(i), Iulius Capitonis und Tismmo Anionis, names of the peregrinae Florentina Campestris, Proba Secundini, Ureluna Valentis and Verrucila Magiri and the single name Mirio.

The prices on the Carnuntum labels are given in Roman currency of the time, based on the denarius: 1 denarius is divided in 4 sestertii and 1 sestertius corresponds to 2 dupondii. To get an idea of the cost of the services, the prices on the Carnuntum tags are compared with those from Siscia []. Most prices are relatively low, suggesting that they cover common services like cleaning, mending and dyeing. Higher prices likely correspond to more expensive services, i.e., more expensive dyes. While prices of more than 7 denarii are rare in Siscia, they seem to be more common in Carnuntum. The labels from Siscia belong to an earlier period (most of them being dated to the 1st and early 2nd century CE), while the find context of the Carnuntum labels would date them to the beginning of the second half of 2nd century CE. Therefore, it can be presumed that the costs of such services in Pannonia Superior increased between the late 1st and the mid-2nd centuries CE. [].

5. Terms Related to Textiles and Services

The most common abbreviations of textiles on Carnuntum labels refer to different types of cloaks such as banata, calthula and casula (19 in total), 10 concern other garments like tunica (see Table 1). Other terms, such as lana (wool), lodix (blanket) or vellus (fleece), are less frequently mentioned (8 in total). Orders for craft services concern about 20 different treatments of garments and textiles (Table 2).

Table 1.

Abbreviations and possible readings related to textiles. The table is based on Römer-Martijnse (1990) [], Radman-Livaja (2014) [], Hermann 2023 [] and Petznek et al. (to be submitted) []. The abbreviation is placed before the parentheses, and the suggested reading is between round brackets.

Table 2.

Abbreviations and possible readings related to services. The table is based on Radman-Livaja (2014) [] and Petznek et al. (to be submitted) []. The abbreviation is placed before the parentheses, and the suggested reading is between round brackets. Any additions that are useful for interpreting the text, such as tingere (to dye), are placed entirely within round brackets.

6. Terms Related to Fumigating, Mending and Perfuming

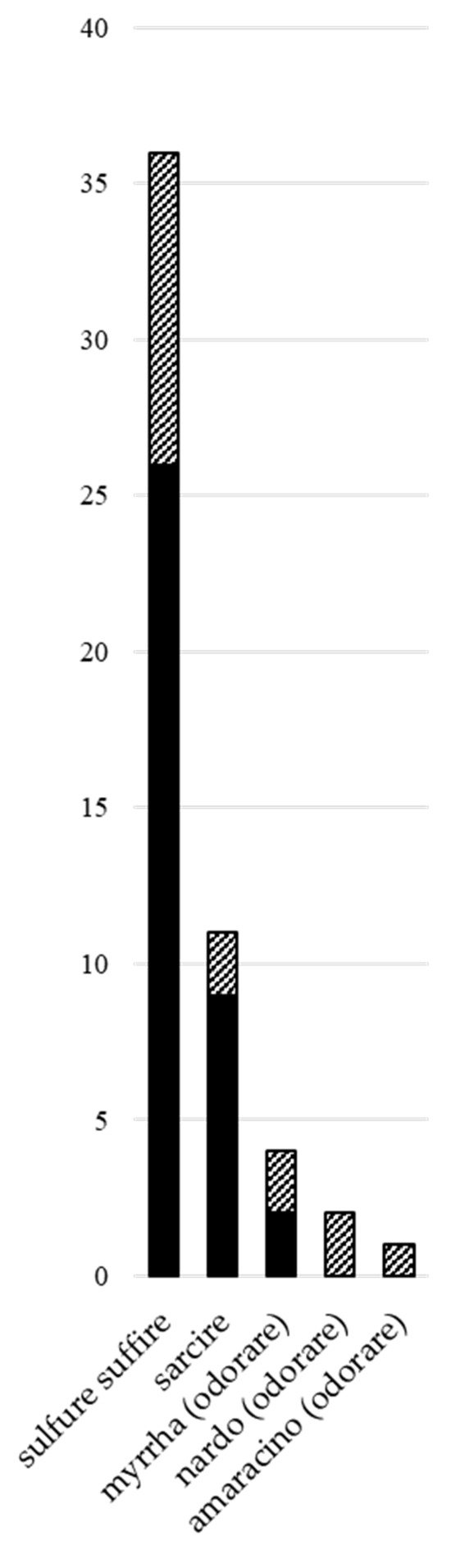

The lead tags mention services related to fumigating textiles with sulphur (sulfure suffire), mending (sarcire) and perfuming (odorare) (Figure 4) [].

Figure 4.

Number of terms on the tesserae related to fumigating with sulphur (sulfure suffire), mending (sarcire), perfuming with myrrh (myrrha odorare), perfuming with nard (nardo odorare) and perfuming with marjoram (amaracino odorare); uncertain readings are highlighted with a hatched pattern.

The abbreviations SVLFVR, SVL and SV (sulfure suffire) refer to the fumigation of clothing with sulphur dioxide (SO2). The inscription on FN523-2011-483 points to the fumigation with sulphur (SV). The client Valerius Porilus had to pay 2 denarii for a garment, which is not further specified. However, some inscriptions can also be interpreted as dyeing of a textile in sulphur yellow (sulfureus). Sulfuring was performed by burning sulphur underneath textiles that were spread out over a portable, igloo-shaped wicker frame (viminea cavea, wicker cage) [] (pp. 30, 114, 117–119, 319, 341–344). It is unclear how commonly fullers actually treated clothes with sulphur and if the portable frame was carried outside the workshop or outside the town walls to do the treatment. The sulphur dioxide was used for bleaching, disinfecting and softening woollen fabrics. A viminea cavea is famously depicted on a Pompeian fresco from fullonica VI 8, 20–21.2, now held at the Naples Archaeological Museum (inv. no. 9974). It shows a worker carrying a viminea cavea and a sulphur-containing pot. The sulphur treatment of dyed woollens made the wool softer, but the colours faded. The Roman politician and scholar Gaius Plinius Secundus (Pliny the Elder, 23/24–79 CE) provided a solution to this problem. In his Naturalis Historia, he describes how faded colours should be refreshed with ‘Cimolian earth’ (creta cimolia), a clay mineral (Plin. NH 35.198) [] (pp. 61, 118, 120) [].

The term mending appears in the inscription ALBANIVS|MARCVS|SAR P|Ӿ I S of FN438-2011-03, suggesting that Albanius Marcus had his garment mended for one and a half denarii. There are two possible interpretations of the abbreviation ‘P’: either the garment began with the letter ‘p’ such as a paenula; or the customer ordered ‘mending and cleaning’, sar(cire) (et) p(urgare). Repairing textiles was already practised in prehistoric times, as evidenced by Hallstatt textiles from the Bronze Age (1500–1200 BCE: HallTex 44, HallTex 236) and the Early Iron Age (800–400 BCE: HallTex 30) [] (pp. 113–115).

Some labels suggest that clothing was perfumed with myrrh, the aromatic resin of the common myrrh (Commiphora myrrha (T.Nees) Engl.), native to Ethiopia, Kenya and the Arabian Peninsula. Perfuming was one of the services provided in fullonicae and seems to be confirmed by the inscription EVCHILVS FVLLO MṾR on tag FN438-2011-48, which can be interpreted that the perfuming with myrrha should be performed by the fuller. Alternatively, it is possible that the client Euchilus is a fullo.

The abbreviation NA, na(rdo) (odorare), on label FN533-2011-10 and N O, n(ardo) o(dorare), on tag FN536-2011-03 could possibly be interpreted as perfuming with the aromatic rhizomes of the Indian nard (Nardostachys jatamansi (D.Don) DC.). There seems to be evidence that the plant was imported from Asia as early as the 1st century CE, since it is referenced as a commercial product in the Periplus Maris Erythraei, a navigation handbook of the Red Sea, (peripl. m.r. 39, 48, 49, 56, 63) []. Nard is also listed among the many trade goods procured from India in the so-called ‘Muziris Papyrus’ from the Vienna Papyrus Collection (SB XVIII 13167) []. Pliny the Elder, however, refers to various materials and their different prices under the term nardus (Plin. NH 12.43, 12.45; cf. Dsc. 1.7–8) [] []. Pliny also mentions saliunca, the Valerian spikenard (Valeriana celtica L.), which grows in regions of Pannonia, Noricum and the Alps, and writes that it was common to place the roots (actually rhizomes) between clothes (Plin. NH 21.43) [] (p. 253) [,,]. The rhizomes are rich in essential oils and have a moth-repellent effect [] (p. 71). H. Genaust generally doubts that nardus refers to Indian nard at all, on the one hand based on its native range in the Himalayas being too remote from the ancient trade routes, and on the other hand because the Indian nard’s morphology bears no resemblance to a spike (nardus) [] (pp. 410–411, 552). He suggests that the term may rather refer to lemon grass (Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf), imported from India. In addition to the Valerian spikenard, he proposes two other sources for nardus native to Europe: lavender (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) and rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus Spenn.).

A reading of ẠMS, occurring on tag FN357-2011-03 is am(aracino) (odorare) s(agum), perfuming a sagum with ointment made from marjoram (Origanum majorana L.).

7. Terms Related to Colours and Textile Dyeing

More than 30 terms on the tesserae refer to colours or dyeing. They were grouped into eight colour categories: yellow, red, blue, purple, green, brown, grey/black and white [,] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Abbreviations and possible readings related to colours and dyeing. The table is based on Radman-Livaja (2014) [], Graßl (2017) [] and Petznek et al. (to be submitted) []. The abbreviation is placed before the parentheses, and the suggested reading is between round brackets. Square brackets indicate alternative meanings of abbreviations and terms belonging to a different colour category to the one in which they were placed and counted. Abbreviations consisting of just one letter (c, f, m or p) are not counted.

In principle, the colour adjectives on the tags can have two meanings. They either describe the colour of the textile or indicate the colour in which the textile should be dyed. For example, caeruleus (blue) could refer to a blue coat, or to dyeing a coat blue. The meaning is usually clear from the context of the entire inscription. Sometimes, inscriptions contain colour terms alongside textile terms and references to services other than dyeing or redyeing. In this case, a colour adjective may have been used to describe the colour of a textile brought to the workshop. If no other service is specified on the tag, it can be assumed that the abbreviation forms part of a dyeing order.

In addition to the colour adjectives, there are also terms that may indicate a dyeing material, such as marigold (caltha), smoke tree, dyer’s sumach or young fustic (cotinus), saffron (crocus), weld (lutum) and kermes (coccineus and cusculium).

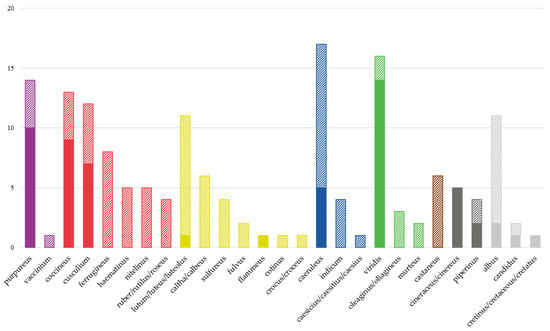

The colour adjectives and dyeing materials were assigned to one of eight colour categories, and the number of times each term appeared on the tesserae was counted (Figure 5). Abbreviations consisting of just one letter were not counted.

Figure 5.

Number of terms on the tesserae related to colours or dyeing materials; uncertain readings are highlighted with a hatched pattern.

8. Dying Techniques, Dyes and Colours

Findings of Roman textiles in Carnuntum do exist [,]. However, they are too degraded to allow a successful dye analysis to be carried out. Therefore, the knowledge of the colourants used in this period is based on ancient written sources and modern research on natural colourants [,,]. Particular attention was paid to the analysis of dyes in archaeological textiles from Central European sites from the same or an earlier period [] [] [] (pp. 148–149) []. Additional knowledge is based on the dye analyses of late antique textiles from Egypt and the Mediterranean region [] (pp. 37–39). Other important sources include archaeobotanical finds of weld (Section 9) and woad (Section 12), and the archaeological finds of marine snails used for producing molluscan purple (Section 13).

Written sources as well as the dye analysis of archaeological textiles shows that dyeing techniques were highly developed long before Roman times. The oldest preserved dyeing recipes for wool are found on a 6th century BCE Late Babylonian cuneiform clay tablet probably from Sippar, a city on the east bank of the river Euphrates in modern Iraq [,,,]. It is housed at the British Museum in London (Inv.-no. BM 62788; BM 82978). This clay tablet mentions vat dyeing, alum as a mordant, mordant dyeing for red with three different madder types, mordant dyeing for yellow, and double dyeing for green and purple.

The following ancient writings were used as sources when researching the inscriptions of the Carnuntum lead labels: The seventh book of De architectura, a ten-volume treatise on architecture by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (about 80/70–after about 15 BCE) is focused on pigments and refers to molluscan purple, woad, and indigo (Vitr. De arch. 7.13–14) []. In 77 CE, Pliny the Elder published the encyclopaedia Naturalis Historia in 37 books, in which he describes dyeing materials and processes from Europe, Egypt and the Near East [,,,,,,]. The five-volume encyclopaedia De Materia Medica, written by the Greek physician, pharmacologist and botanist Pedanius Dioscorides (about 40–about 90 CE) reflects the pharmacological knowledge of antiquity [,,]. However, he also mentions that some medicinal plants can be used for dyeing [] (pp. 26–28). Pliny the Elder and Dioscorides are both important sources of information on dyeing materials and techniques. Section 8, Section 9, Section 10, Section 11, Section 12 and Section 13 provide detailed information on the references for alum, alkanet, madder, kermes, woad, indigo, molluscan purple, cotinus and vaccinium.

Although the Papyrus Graecus Holmiensis and the Papyrus Leidensis X were created later than the Carnuntum lead labels, they are good sources of information on dyeing. They were discovered in tombs, presumably near Thebes, and contain recipes for colouring metals, stones and minerals, imitating gold and silver and dyeing textiles. Dating from the 3rd and 4th centuries CE, some of these recipes may originate from an earlier period [,,,]. Of the 156 recipes in the Papyrus Graecus Holmiensis, 71 concern dyeing, including dyeing with woad, madder, and kermes. The Papyrus Leidensis X contains 99 recipes, eleven of which are for dyeing wool [] (pp. 29–35). The papyri mainly contain instructions for dyeing purple shades with vegetable dyes (Section 13) and to a lesser extent for creating shades of blue, red, yellow, brown and green.

Two written sources refer to Asian trade goods used in textile production. The Periplus Maris Erythraei (Periplus of the Red Sea) is a Graeco-Roman navigation handbook written in Greek in the mid-1st century CE, which provides information on ports along the coasts of the Red Sea, Northeast Africa, Arabia and Southwest India []. It mentions trade goods from India such as pepper, nard, lac dye, indigo, cotton and silk. The so-called Muziris Papyrus (SB XVIII 13167), written in Greek in the mid-2nd century CE is housed at the Papyrus Collection in Vienna []. It documents a contract with an Alexandrian merchant, who imported merchandise from Muziris on the Malabar coast in South India, and the goods traded included nard, pepper, ivory, precious stones and fabric.

Ancient and historic textile dyeing uses colourants, which include soluble dyes, soluble tannins and insoluble organic pigments as well as three dyeing techniques—direct, mordant and vat dyeing [,,,,,,]. The colour palette was created by applying these techniques and combining them in double dyeing (Table 4).

Table 4.

Colours and ancient textile dyeing. Column 1 attempts to reproduce the approximate colour tone that can be achieved with the dyeing materials and dyeing processes. The table is based on the main sources on natural dyes and their analysis [,,,] and on publications about dyes in archaeological textiles [,,,].

8.1. Direct Dyes and Direct Dyeing

Tannins and some natural soluble dyes bind directly to fibres, creating various colour shades without a mordant or additive [] (pp. 25–26). The brown tones dyed with tannins are colourfast, while direct dyes provide non-colourfast shades. Yellow can be produced with the carotenoid dye crocetin from saffron (Crocus sativus L.), red with the chalcone dye carthamin from safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.), and brown with the green parts of common walnut (Juglans regia L.), which contain tannins and the naphthoquinone dye juglone.

Orchil (fucus), which is prepared from lichens such as Roccella tinctoria DC., produces purple shades [,] (pp. 274–283, pp. 485–503). Pliny the elder mentions the purple colour obtained with orchil (Plin. NH 13.136, 26.103, 32.66) [,,]. However, it is thought that this material was primarily used for pre-dyeing molluscan purple [] (p. 244). This suggests that the poor colourfastness of this dyeing material was known in ancient times. Another plant, the dyer’s alkanet (Alkanna tinctoria (L.) Tausch, see Section 8.2), was also used to create purple tones. However, these colours were not permanent either. The Papyrus Graecus Holmiensis and the Papyrus Leidensis X both refer to orchil and alkanet in recipes for shades ranging from purple to red [] (pp. 29–34, 49–50, 83–85).

8.2. Mordant Dyes and Mordant Dyeing with Alum

Most natural dyes are mordant dyes. In principle, these dyes can be used without mordants, but this results in pale colours that are not permanent. Intense and durable colours can only be achieved by fixing the dyes to the fibres with mordants [] (pp. 25–27). These dyes include yellow flavonoid dyes as well as red anthraquinone dyes derived from scale insects (dye insects) and plants belonging to the Rubiaceae family.

Flavonoids are widespread in the plant kingdom. Therefore, it can be challenging to identify plant species based on dye analysis of yellow-dyed archaeological textiles. Since prehistoric times, weld (Reseda luteola L.) has been the most important dye plant for yellow in Europe [] (pp. 175–177). The green parts of the plant contain the yellow flavones luteolin and apigenin as main dyes. Both the dyer’s broom (Genista tinctoria L.) and the common sawwort (Serratula tinctoria L.) are also sources of luteolin and apigenin [] (pp. 214–231). The common marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) the field marigold (Calendula arvensis (Vaill.) L.) and the heartwood (young fustic) of the dyer’s sumac or European smoketree (Cotinus coggygria Scop.) provide yellow flavonols [,] (pp. 175–176, pp. 176–181) [].

Dye insects, belonging to the superfamily Coccoidea (scale insects) are sources of anthraquinones and were applied in ancient textile dyeing [,] (pp. 52–91, pp. 607–656) []. Kermes (Kermes vermilio Planchon, 1864) consists of adult females that were collected from the branches of kermes oaks (Quercus coccifera L.). The main dye identified in kermes-dyed textiles is kermesic acid. Armenian cochineal (Porphyrophora hamelii Brandt 1833) lives on the roots of grasses in the region of Mount Ararat and the Caucasus, and Polish cochineal (Porphyrophora polonica (Linnaeus, 1758)) is found on the roots of perennial knawel (Scleranthus perennis L.) and various other plants in north-eastern Europe. Both species are known as ‘root cochineal’ because they live on plant roots, and the dyeings produced with them are usually impossible to distinguish by dye analysis. The characteristic minor dyes present alongside with the main dye carminic acid are often no longer detectable in archaeological textiles. As long as the textiles are not too degraded, it is possible to identify the species of the dye insect that has been used worldwide for dyeing [] (pp. 66–72).

The rhizomes of Rubiaceae species contain various red anthraquinone dyes and have been worldwide used for dyeing since prehistoric and ancient times [,] (pp. 92–110, pp. 107–129). In ancient Europe, dyer’s madder (Rubia tinctorum L.) was the most important plant of this family. Textiles dyed with the rhizomes of this plant usually contain more alizarin than purpurin, or an equal amount of both dyes. However, there are numerous red-dyed textiles that contain purpurin as the main dye [] (pp. 148–153) The terms ‘madder type’ or ‘Rubiaceae species’ are used in cases where the species Rubia tinctorum L. cannot be clearly identified [,] (pp. 374–376, pp. 6–12). Current research aims to reveal the causes. Other species of the Rubiaceae family, such as dyer’s woodruff (Asperula tinctoria L.) and bedstraw species (Galium spp.) contain purpurin as the main dye. Could they have been used alone or mixed with madder? Other theories suggest that the composition of the dyes may be affected by the way the rhizomes are treated or by particular dyeing techniques [,] (pp. 109–110, pp. 79–81) [].

Red to purple and violet colours with low colourfastness are created by anthocyanins from fruits like the bilberry or European blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) [] (pp. 243–245) and maybe from leaves of the European smoketree (Cotinus coggygria Scop.) (see Section 13). Non-colourfast purple shades can also be obtained from the roots of dyer’s alkanet (Alkanna tinctoria (L.) Tausch), which contain the naphthoquinone dye alkannin [,] (pp. 44–47, pp. 60–63).

What can be said about the mordants available during Roman times? The use of club mosses, which accumulate aluminium salts in the cell sap [] (pp. 33–34), was probably limited to domestic dyeing. Tannins can be used as mordants, but they produce darker, less vivid shades because of their brown natural colour. The most important mordants are metal salts, whose polyvalent metal ions form strong bonds between dye and fibre molecules. Alum (KAl(SO4)2·12H2O) is a potassium aluminium sulphate. It has been the most commonly used mordant since ancient times. The Greek historian Herodotus (around 484–around 425 BCE), Pliny the Elder and Pedanius Dioscorides describe various kinds of alum, their deposits in the Mediterranean region and the good quality of Egyptian alum (Plin. NH 33.94, 35.183–190; Dsc. 5.106) [,,]. Alum has little effect on the colours but intensifies them. By contrast, colour changes are caused by iron and copper ions, whether they come from mordants (salts), metal vessels, or metal waste (see Table 4).

8.3. Vat Dyes and Vat Dyeing

Vat dyeing is a dyeing technique for insoluble organic pigments (vat dyes, indigoid dyes). Two techniques had to be developed. The first concerns the preparation of organic pigments from water-soluble precursors (chromogens) present in indigo plants and snails from the Muricidae family (molluscan purple), and the second technique is vat dyeing. By reduction in an alkaline solution, the water-insoluble pigments convert into water-soluble, greenish-yellow leuco forms. When the textile is immersed in the vat, the leuco-forms are absorbed by the fibres. After a while, the textile is taken out of the vat and exposed to the air. The contact with oxygen in the air causes oxidation and reconverts the greenish-yellow water-soluble leuco-forms into water-insoluble pigments, which adhere to the fibres [] (pp. 26–29).

Indigotin, a vat dye obtained from the leaves of indigo plants, is the only natural colourant for dyeing blue. The most important sources in Roman times were woad (Isatis tinctoria L.) in Europe and Indian indigo (Indigofera tinctoria L.) in India. It should be noted that dye analysis cannot determine whether woad, indigo, or another indigotin source was used to dye a textile [] (p. 257).

6,6’-dibromoindigotin, 6-monobromoindigotin, indigotin and related indigoids of molluscan purple are derived from hypobranchial glands of marine snails from the Mediterranean Sea, mainly from the banded dye-murex (Hexaplex trunculus Linnaeus, 1758) [,,] (pp. 553–586, pp. 56–65, p. 203). This species has been identified in archaeological textiles as the primary source of both indigotin-rich blue-purple and dibromoindigotin-rich red-purple [] (p. 87). The spiny dye-murex (Bolinus brandaris (Linnaeus, 1758) and the red-mouthed rock shell (Stramonita haemastoma (Linnaeus, 1767)) provide dibromoindigotin-rich red-purple and could be added to the Hexaplex trunculus pigment to create more reddish-purple tones [] (pp. 256, 288–300).

8.4. Double Dyeing and Shading of Colours by Copper- and Iron-Based Mordants

The range of textile colours could be expanded by dyeing in two or more different dye baths (double dyeing, top dyeing, over-dyeing, multiple dyeing process) [] (pp. 21–23). Orange shades were created using yellow and red mordant dyes. True greens were achieved by double dyeing, blue in a woad vat and yellow in a dye bath prepared with weld or another flavonoid-containing plant. In antiquity, it was common to produce purple nuances by dyeing blue in a woad vat and dyeing red with mordant dyes from a Rubiaceae species or a dye insect.

Shading of colours with mordants is also an old technique. Treating a textile with an iron or copper salt solution changes the colour. The yellow flavonoid dyes give brown shades with iron-containing mordants and olive-green tones with copper-containing mordants. Red anthraquinone dyes with iron-based mordants lead to brown, purple and violet hues. Dark brown to black colours can be achieved by combining tannins with iron-based mordants to create the so-called ‘iron-gall black’.

It is assumed that the colours mentioned on the Carnuntum tags were created using these dyeing methods, or a combination of them. Brown, yellow and red could be achieved by direct dyeing, blue and purple by vat dyeing and red and yellow by mordant dyeing based on alum-mordant. The range of textile colours could be expanded to include green, purple and black by double dyeing. The application of iron- and copper-based mordants resulted in shades of olive, purple and black (Table 4).

9. Terms Related to Yellow

Many abbreviations on the Carnuntum tags refer to yellow colours or dyes, such as calbeus (green-yellow), croceus, crocinus or crocatus (saffron yellow), croco tingere (to dye with saffron) flammeus (flaming yellow or flaming red), fulvus (a shade of yellow), luteolus (yellowish), luteus (golden yellow), lutum (weld), murreus or myrreus (myrrh-coloured, brownish to yellowish) and sulfureus (sulphur-coloured).

The abbreviation FV can be interpreted as fulvus (yellow tone) or fuscus (brown tone) and SV and S could mean sulfureus (sulphur yellow) but also sulfure suffire (fumigating with sulphur).

Label FN532-2011-15 contains PAN (pannum, cloth) together with FLAM (flammeus, flaming), meaning flaming yellow or flaming red. This colour adjective was classified as yellow based on Pliny the Elder. He states that yellow was highly esteemed and was the exclusive colour of the bridal veil (flammeum) (Plin. NH 21.46) [], which was probably dyed with weld (lutum) [] (p. 250).

The abbreviations LVT or LV could refer to lutum (weld) but also to luteus (golden yellow) or luteolus (yellowish). The reading of lutum is very likely on tag FN553-2011-153 (COLOṚ Ṭ Ị∣C̣VM LV∣Ӿ IIII S =−) and could mean dyeing with weld, color(e) ti(ngere) cum lu(to), for the price of 4 denarii and 3 sestertii. Since antiquity, weld (Reseda luteola L.) has been the most important source for yellow. The species, originally distributed in West Asia and the Mediterranean region, has spread to large parts of Europe by cultivation. Seed finds from the Neolithic to the Roman period prove its distribution in Central and Western Europe [,] (pp. 151–157, pp. 44–46).

The inscription C̣R on tag FN532-2011-17 could be read as dyeing saffron-yellow or dyeing yellow with the red stigmas of saffron crocus, cr(oceo) or cr(oco) (tingere). Ancient sources refer to saffron yellow robes [] (p. 250). However, it is uncertain whether these garments were dyed with the precious saffron or with other yellow-dyeing plants. In the case of the label from Carnuntum, it can also be assumed that textiles were not dyed with the expensive saffron, but saffron yellow with another plant, such as weld. Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) was mentioned by ancient writers. The epic poem Aeneid, written by the Roman poet Publius Vergilius Maro (70–19 BCE), describes saffron as a dyeing material (9.614) []. In Naturalis Historia, Pliny the Elder mentions wild saffron and the cultivation of saffron in Cilicia and Lycia (Asia Minor), Thera (Santorini), Sicily and Italy, but not its use for dyeing (Plin. NH 21.31) []. Saffron crocus is native to Greece and is one of the oldest cultivated plants, growing in Syria and Egypt. In the Middle Ages, the plant was cultivated and traded in Lower Austria, but there is no evidence yet that it was grown in Pannonia during antiquity.

The abbreviation CAL on tag FN438-2011-08 refers to another plant for yellow: the common marigold (Calendula officinalis L.), which could also include the field marigold (Calendula arvensis (Vaill.) L.) [] (p. 69) []. E. Miramontes Seijas also considers the yellow button (Anacyclus radiatus Loisel) to be a possible interpretation for caltha [] (pp. 32–33). On this label, the client Aurelius Iustianus is mentioned together with the inscription M VI R M CAL∣Ӿ II £. An interpretation is m(antella) sex r(etingere) m(antella) cal(beo), cal(laino) or (cum) cal(tha). Six mantles should be redyed, the mantles should be dyed green-yellow or light-green, or yellow with caltha. Another interpretation is m(antellum) vir(idi) m(antellum) cal(beo), cal(laino) or (cum) cal(tha) (tingere) and would mean that he wanted a mantle to be dyed green and another mantle to be dyed green-yellow or light green or yellow with caltha.

The inscription on tag FN357-2011-01 (LẠCOTR) could be read as redyeing a lacerna with cotinus, la(cernam) cot(ino) r(etingere). Dyeing can be performed with different parts of dyer’s sumac or European smoketree (Cotinus coggygria Scop.). The abbreviation was assigned to yellow, because the heartwood (young fustic), containing the flavonol fisetin, dyes yellow. However, the tannin- and anthocyanin-rich leaves (sumach) give textiles a reddish-brown (purple) colour (see Section 13).

10. Terms Related to Scarlet Red

The abbreviations COC (coccineus, scarlet, crimson) and CVS (cusculium, kermes) are often found on the lead tags referring to popular reds from dye insects.

The inscription on tag FN438-2011-13 contains the term coccineus (FORTIS∣TIRTI∣C M COC∣Ӿ II £) and could mean that Fortis Terti(i) ordered the dyeing of a mantle in scarlet, c(olorare) m(antellum) coc(cineo) (tingere) at a cost of 2 denarii and 1 dupondius.

Label FN438-2011-67 refers to kermes and perfuming. The inscription AḌNV.Ọ MA∣TVRI CVS∣MVR∣Ӿ S could indicate that Adnuo? Maturi, wanted an unspecified garment dyed scarlet with kermes, cus(culio) (tingere) and perfumed with myrrh, myr(rha) (odorare). He had to pay 2 sestertii (1/2 denarius).

In antiquity, red anthraquinone dyes were derived from scale insects (dye insects) which dye various shades of scarlet red. Besides molluscan purple, these dyeing materials were highly esteemed and delivered colours of excellent quality. Furthermore, they were expensive and enjoyed a high status. In ancient times, a distinction was made between purple obtained from sea snails and the ‘Phoenician colour’ from kermes [] (p. 249). Kermes (Kermes vermilio Planchon, 1864), the most important dye insect in antiquity, was native to the Mediterranean region. Pedanius Dioscorides wrote about kermes (Dsc. 4.48) []; and Pliny the Elder mentions the material as granum (grain, seed) and coccus (von griechisch κόκκος, berry) due to the grain-like appearance of the female insects (Plin. NH 9.141, 22.3), and only once he used the term cusculium (or scoletium: see Plin. NH 16.32) [,,]. Pliny describes its feeding on hostplants in Asia Minor (Galatia, Pisidia, Cilicia), Sardinia and Africa as well as its application for military cloaks for high-ranking officials (paludamenta imperatoria: see Plin. NH 16.32, 22.3). Kermes has been identified by dye analyses in textiles from the Celtic settlements in Eberdingen-Hochdorf in Germany (530–520 BCE) and Dürrnberg in Austria (6th–2nd centuries BCE), indicating that kermes, kermes-dyed yarns or textiles had already been imported from the Mediterranean region in the Iron Age [,] (p. 244, pp. 169–170). It remains an open question whether kermes or other dye insects were imported to Carnuntum.

11. Terms Related to Red

In addition to the terms relating to kermes, the adjectives ruber (red), rutilus (reddish), roseus (rose-coloured, rosy, pink) and haematinus (blood-red) appear on the Carnuntum tags. The colour adjective nitelinus (dormouse coloured) means a reddish or reddish-brown shade. Ferrugineus can be interpreted as rust-like (rust-red to rust-brown) or iron-like (grey) and is placed into the colour category red.

An example of ruber is the inscription on tag FN532-2011-03 (FLORIINTINA∣ CAMPIISTRIS∣ S M T I N R Ӿ IIII). It seems that Florentina Campestris wanted two garments dyed red, s(agum) (et) m(antellum) tin(gere) r(ubro), for the price of 4 denarii. It can be assumed that dyer’s madder (Rubia tinctorum L.) was available to the dyers. This plant is native to an area extending from south-east Europe and the Mediterranean region to the western Himalayas. It has been introduced to other parts of Europe and Africa through cultivation. In De Materia Medica (Dsc. 3.160), Pendanius Dioscorides refers to madder as erythrodanon and mentions its cultivation in Thabana (Galilee), Ravenna (Italy) and Caria (Asia Minor) []. Pliny the Elder mentions rubia as a trade product as well as for dyeing wool and leather. He writes about the excellent quality of madder grown near Rome and states that almost all provinces are full of it: “... et omnes paene provinciae scatent ea” (Plin. NH 19.47, 24.94) [,] [] (p. 250). It can be assumed that textiles were dyed red with dyer’s madder in Carnuntum, but there is so far no evidence of its cultivation in Upper Pannonia.

12. Terms Related to Blue

Terms for blue on the lead tags are caeruleus (blue), caesius, caesicius or caesitius (greyish or greenish blue), and the letter I could be interpreted as a colour like i(ndicum).

The adjective caeruleus occurs on tag FN533-2011-02 (VIIRRVCIḶ∣Ạ MAG̣ỊRỊ∣G II PAL CIIR Ӿ I £). A proposed reading is: Verrucila Magiri ordered two gausapae and one pallium to be dyed blue for the price of 1 denarius and 1 dupondius (Figure 3a–g). In the European regions of the Roman Empire, the organic pigment (vat dye) indigotin was obtained from the leaves of woad (Isatis tinctoria L.), native to eastern and south-eastern Europe [,] (pp. 141–147, pp. 52–53). Dyeing with woad was already known in the Bronze Age (1500–1200 BCE), as proven by dye analyses of Hallstatt textiles. Numerous finds of woad, woad seeds and their imprints in ceramics are known from prehistoric Europe dating back to the Iron Age (6th to 5th century BCE) [] (pp. 52–53). Archaeologists working on a rural settlement site at Roissy north of Paris, excavated 104 woad seeds together with other cultivated plants—mostly emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccum Schrank)—in a storage pit dated to the 5th or 4th century BCE []. This suggests that woad was cultivated and intentionally sown as early as the La Tène culture in Iron-Age Europe (around 450–40 BCE).

From India, the Romans imported another blue colourant, indigo. It is obtained particularly from Indigofera tinctoria L., native to Asia and Africa. De Architectura by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio mentions woad (precipitated on chalk) and indigo as pigments for fresco painters (Vitr. De arch. 7.13–14) []. The Periplus Maris Erythraei lists indigo (indikon melan) among other trade goods, such as lac dye, cotton, silk and nard, transported from India to the West (chapt. 39) [] (p. 75). Pedanius Dioscorides refers to indigo by the Greek term indikon (Dsc. 5.107) and Pliny the Elder by the Latin term indicum (Plin. NH 33.163, 35.46) [,,]. Both writers describe two origins of indigo, namely plants native to India and scum floating on top of copper kettles. In the parlance of modern indigo dyers, this foam is known as the ‘flower’. It was collected by ancient painters and used, in particular, to create lines that separated shadow from light [,] (p. 285, pp. 254–256). However, there is no written evidence that indigo was used in Roman textile dyeing. If the ‘I’ on the tags FN438-2011-29, FN438-2011-30 and FN532-2011-39 is interpreted as ‘indicum’, this would most likely mean an indigo-blue colour, but not the use of indigo as a dyeing material.

13. Terms Related to Purple

The colour purpureus (purple) is one of the most frequently mentioned colour names on the Carnuntum lead tags. It should be mentioned that purgare (to clean) or purus (pure) cannot be completely excluded as a meaning of PVR. Other abbreviations indicating purple colours are COT, meaning cotinus, and VA, meaning vaccinium.

Ulpius Bato appears on the front and back of tag FN483-2011-08. He wanted his textiles dyed purple or an unspecified service for his purple textiles, for a cloth (pannum) he had to pay 3 denarii (front: PẠṆ PṾR∣Ӿ III) and for a cloak (pallium) three and a half denarii (back: PAL PVR∣Ӿ III S).

The frequent occurrence of the term purpureus suggests that purple shades were popular, but it does not indicate which dyeing techniques and materials were applied. The most precious dyeing material of antiquity is molluscan purple, also known as Tyrian purple, named after the Phoenician city of Tyre. Another origin is the Minoan civilisation of the Aegean. The earliest textile finds dyed with molluscan purple are known from the settlement mound of Chagar Bazar in northern Syria (18th–16th centuries BCE); the earliest evidence of molluscan purple in wall paintings are from the Aegean Sea (17th century BCE or earlier) [,,]. Marcus Vitruvius Pollio refers to this material used as a pigment (Vitr. De arch. 7.13–14) []. Archaeological finds and contemporaneous texts indicate centres of purple production and purple dyeing, situated on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, as far north as the Adriatic Sea [] (p. 574) []. Pliny the Elder writes about the colourfast purple dye of marine creatures, their origin, qualities and dyeing methods (Plin. NH 9.124–141) [] [,] (pp. 11–14, pp. 235, 242). The use of molluscan purple reached a peak in the 1st century CE, which Pliny the Elder describes as purpureae insania, literally “purple mania” (Plin. NH 9.127). It seems that a great variety of purple shades, from molluscan purple and/or combinations of plant dyes, was not only worn by the highest rank of society. The Papyrus Graecus Holmiensis contains recipes for creating purple to reddish tones using alkanet, orchil, madder, kermes and woad. Multiple dyeing with woad, kermes and ‘rustic’ orchil produced a scarlet shade (P. Holm. 122) [] (p. 77, no. 117), while double dyeing with woad (‘blued’ wool) and madder gave a purple shade (P. Holm. 159) [] (pp. 84–85).

It is reasonable to assume that the people of Carnuntum wore imported clothing dyed with real purple. For textile dyeing in Carnuntum, it seems more likely that other dyeing techniques were used to achieve purple shades, such as dyeing with madder and an iron mordant or double dyeing, blue in a woad vat and red with madder or perhaps kermes.

The inscription COT on tag FN357-2011-01 (LẠCOTR) could be read as redyeing a lacerna with cotinus, la(cernam) cot(ino) r(etingere). Dyeing yellow with the heartwood (young fustic) of the European smoketree (Cotinus coggygria Scop.) was already discussed before (see Section 9 above). Pliny the Elder mentions cotinus, a shrub growing in the Apennines that is suitable to dye linen purple (Plin. NH 16.73-74) []. He is presumably referring to the leaves of this plant. They mainly contain tannins, as well as flavonols and anthocyanins and due to their high tannin content, they were primarily used together with iron-based mordants to dye black [] (pp. 383–384). Without an iron-based mordant, the presence of anthocyanins alongside tannins and flavonols could have resulted in purple (reddish-brown) hues.

The abbreviation VA on tag FN532-2011-19 could be understood as varius (multi-coloured), but vaccinium is also an option. According to Pliny the Elder, the vaccinium plant is found in damp places. In Italy, it grows near bird snares; in Gaul, it provides a purple dye for slave clothes (Plin. NH 16.77) []. This plant is usually interpreted as bilberry, the European blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) [,] (p. 98, pp. 253–254). However, the identification is uncertain. H. Genaust, a researcher of plant name etymology, claims that vaccinium probably does not refer to blueberries, but to the deep blue flowers of an unidentified plant [] (pp. 295–297, 673).

14. Terms Related to Green

Colour adjectives which point to green shades are viridis (green), oleaginous or oliagineus (olive green) and murteolus, murteus, myrteolus or myrteus (myrtle-coloured, greenish to brownish). The abbreviation P is sometimes interpreted as prasinus, leek green.

Many labels show the abbreviation VIR for viridis. The client Iulius Capitonis appears on tag FN438-2011-44 together with BẠṆ∣VIR Ӿ II S =−, which could mean that he ordered a cloak to be dyed green, ban(atam) vir(idi) (tingere), for the price of 2 denarii and 3 sestertii.

Tag FN546-2011-644 belonged to Tismmo Anionis, who wanted a tunica dyed in olive green, TṾN ỌLA, tun(icam) ol(e)a(gineo) (tingere). MV on tags FN438-2011-06 and FN553-2011-153 is interpreted as murteus, a greenish, perhaps brownish colour.

True green tones can only be achieved by double dyeing, while olive green and brownish green shades could be achieved by combining yellow flavonoid dyes with copper- or iron-based mordants.

15. Terms Related to Brown, Grey and Black

These colour categories include the adjectives castaneus (chestnut brown), fuscus (dark brown), cineraceus or cinereus (ash grey), piperinus (pepper-coloured, grey to black or brown), murinus (mouse grey, marten-coloured means a brownish shade), murreus or myrreus (myrrh-coloured, brownish) and murteolus, murteus, myrteolus or myrteus (myrtle-coloured, greenish to brownish).

An example for brown is tag FN438-2011-32 (ṾRIILVNA ṾALIIN∣TIS ḄAN CAST∣Ӿ VIIII). The most likely reading is, that Ureluna Valentis ordered a banata to be dyed chestnut brown, ban(atam) cast(aneo) (tingere).

The abbreviation CIN (cinereus) occurs in combination with another colour, together with COC (coccineus) on the tags FN438-2011-32, FN438-2011-33, FN438-2011-34, FN532-2011-42 and together with VIR (viridis) on tag FN532-2011-19. It is assumed that the garments show a grey colour and are decorated in scarlet or green.

An example of piperinus is tag FN438-2011-20 (IVSTIA SATVRNINA∣LOD PIPIR∣Ӿ I S). An interpretation is that Iustia Saturnina brought a blanket to be dyed in a pepper-coloured shade (grey to black or brown), lod(dicem) pipir(ino) (tingere). She had to pay one and a half denarii. Pipirinus is either a vulgar form of the adjective piperinus, or simply a slip of the pen (lapsus calami).

Brown shades can be obtained by using tannins without additives or by yellow flavonoids with iron-based mordants. Dark brown, grey and black shades are achieved by double dyeing, dyeing blue to dark blue in a woad vat, combined with dyeing in a dye bath prepared with red mordant dyes and/or a dye bath with yellow mordant dyes. The other technology combines tannins and iron-based mordants to creates ‘iron-gall blacks’, ranging from dark brown and dark grey to black.

16. Terms Related to White

Three terms for the colour white appear on the Carnuntum tags, albus (dull white), candidus (bright white) and cretaceus (white similar to chalk).

It is assumed that the abbreviation TA, which appears on several tags, means t(unica) a(lba).

The inscription on tag FN438-2011-46 (MIṚIO∣G̣Ṿ SV∣Ӿ XII CAN) could mean that a g(a)u(sapa) of Mirio was treated with sulphur, su(lfure suffire), to obtain can(didus), a brilliant white, and he paid 12 denarii for this service.

PROBA SIICVNDI∣NI S CRIITIṆVM occurs on the back of tag FN438-2011-37. It should be noted that there are no recorded adjectives like cretinus, a, um in literary Latin. However, we would suggest that this is a vulgar form of familiar adjectives such as cretaceus (similar to chalk) or cretatus (white-chalked). Proba Secundini either brought a chalky-white cloak, s(agum) ‘cretaceum’, for an unspecified service, or she wanted her sagum to be whitened with chalk, s(agum) ‘cretatum’. The price was 3 denarii. The treatment with chalk gives a lustre to clothing and was one of the last steps in the fulling process [] (pp. 119–121).

Natural dyes and dyeing processes cannot achieve white shades. Non-pigmented wool and white linen were regarded as the most favourable raw materials for dyeing. In prehistoric times, white wool was obtained for dyeing by separating it from the multicoloured fleeces of ancient sheep breeds. Later, humans started to breed white sheep. The invention of bleaching processes enabled the natural beige colours of plant and wool fibres to be changed into white.

The importance of white has been described by the Roman author Lucius Iunius Moderatus Columella († around 70 CE) in his De re rustica (7.3.4): color albus cum sit optimus, tum etiam est utilissimus, quod ex eo plurimi fiunt, neque his ex alio, “While white is the best colour, it is also the most useful, because very many colours can be made from it; but it cannot be produced from any other colours.” English translation: [] (p. 235).

17. Conclusions

A cesspit excavated in 2011 at Petronell Castle in Austria was located in the former Roman civil town of Carnuntum, Pannonia Superior, and was dated to the mid-2nd century CE based on coin finds and ceramics. The cesspit served as a latrine, and the artefacts found in it provided valuable insights into the flora and fauna, the health, eating habits and the way of life of the inhabitants of ancient Carnuntum. A total of 179 inscribed lead tesserae were discovered, providing historical insights into the activities of an ancient workshop specialising in fulling and cleaning (fullonica), as well as dyeing and redyeing (officina infectoria and officina offectoria). The labels contain a rich terminology relating to textiles, garments, services, colours, client names and prices. The lead tags enable to reconstruct the workshop’s workflow and the exchange between client and contractor. The terms for services, clothing and colours expand the knowledge of the textile industry during the Roman imperial period. While the prices indicate the cost of the services provided at the workshop, the personal names offer a particularly interesting insight into the average population of Carnuntum in the mid-2nd century CE. They include people who may not have had the financial means to erect funerary stones or votive monuments, meaning they would otherwise have been invisible in the epigraphic record.

The terms related to colours and dyeing offer insight into the colourful clothing worn in the 2nd century Carnuntum. They also allow to draw conclusions about the materials and techniques used for dyeing. The frequently attested colour adjective caeruleus (blue) refers to different blue tones that could be produced by vat dyeing using woad (Isatis tinctoria L.), the locally grown dye plant. Perhaps the dyers were also familiar with the blue colour of indigo, even though they did not use the dyeing material from India for textiles. The numerous names pointing to yellow hues suggest that several plant materials were available for yellow mordant dyeing. The tesserae’s inscriptions seem to feature plants such as weld (Reseda luteola L.), marigold (Calendula spp.), smoke tree (Cotinus coggygria Scop.) and saffron (Crocus sativus L.). When it comes to green, viridis (green) is the most common umbrella term. Most of the green shades could only be achieved by double dyeing, combining dyeing in a woad vat for blue and the dyeing with yellow mordant dyes. On the other hand, olive green tones could be achieved using yellow mordant dyes and copper-based mordants.

The largest numerical group comprises the colours purpureus (purple), coccineus and cusculium (scarlet red) and ruber (red). The popularity of red and purple tones, as documented in written and art historical evidence, is likely also true for the province of Pannonia Superior. Red and scarlet tones were dyed with mordant dyes. It can be assumed that red shades were created with dyer’s madder (Rubia tinctorum L.) and scarlet shades with kermes (Kermes vermilio Planchon, 1864). The dyers in Carnuntum probably produced purple tones, primarily by combining dyeing blue in a woad vat with dyeing red using mordant dyes.

Brown, grey and black tones are rarely mentioned on the tesserae. This may be because these colours were readily available in undyed sheep’s wool, so that no elaborate dyeing process was required. White fibre materials, which were particularly suitable for dyeing, could be obtained in various ways. White sheep’s wool could be sorted from the fleece of piebald breeds or obtained from white sheep breeds. Last but not least, the wool and linen fibres, which originally had a rather beige or grey colour, could be bleached.

The Roman textiles excavated in Carnuntum have degraded so badly that it is impossible to analyse their dyes successfully. Therefore, the inscriptions on the lead tags are a particularly valuable source of information on the dyeing materials and techniques used at the time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.H.-d.K. and B.P.; methodology, I.R.-L., B.P., R.H.-d.K. and I.B.; validation, R.H.-d.K., I.R.-L., B.P., I.B. and A.G.H.; formal analysis, I.R.-L., B.P., I.B., A.G.H. and R.H.-d.K.; investigation, I.R.-L., B.P., R.H.-d.K., I.B. and A.G.H.; resources, B.P.; data curation, I.R.-L., B.P., R.H.-d.K., I.B. and A.G.H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.H.-d.K.; writing—review and editing, A.G.H., I.R.-L., I.B. and B.P.; supervision, A.G.H.; project administration, B.P.; funding acquisition, B.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Jubiläumsfonds der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank (Anniversary Fund of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank, OeNB), project title: Handel, Wirtschaft, Kultur und Naturraum in der mittleren Kaiserzeit im Raum Carnuntum, funding number: 15007, project coordinator: Beatrix Petznek).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data presented in this study are available on request from the authors. A book will be published that will contain all the data resulting from this research: Petznek, B.; Heiss, A. G.; Schwab, R.; Hofmann-de Keijzer, R.; Radman-Livaja, I., Eds. Handel, Wirtschaft, Kultur und Naturraum in der mittleren Kaiserzeit im Raum Carnuntum. Interdisziplinäre Analysen der römischen Latrine mit Preisschildern in Carnuntum (Schloss Petronell). Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2026, manuscript to be submitted.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Egger, R. Epigraphische Nachlese, Bleietiketten aus dem rätischen Alpenvorland. In Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Institutes in Wien 1961–1963; Austrian Archaeological Institute: Vienna, Austria, 1963; Volume 46, pp. 190–191. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, E. Beschriftete Bleitesserae, eine bisher wenig beachtete Denkmälergruppe. In Proceedings of the VIIe Congrès International D’épigraphie Grecque et Latine, Constantza, 7th International Congress of Greek and Latin Epigraphy, Constanța, Romania, 9–15 September 1977; Editura Academiei: București, Romania; Société d’édition Les Belles Lettres: Paris, France; pp. 489–490. [Google Scholar]

- Römer-Martijnse, E. Beschriftete Bleietiketten der Römerzeit in Österreich. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Paci, G. Etichette plumbee iscritte. In Commentationes Humanarum Litterarum 104, Proceedings of the Colloquii Epigraphici Latini, Helsingiae, Finland, 3–6 September 1991; Suomen Tiedeseura: Helsinki, Finland, 1995; pp. 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pfahl, S.F. Instrumenta Latina et Graeca Inscripta des Limesgebietes von 200 v. Chr. bis 600 n. Chr.; Bernhard, A.V., Ed.; Greiner: Weinstadt, Germany, 2012; pp. 203–207. ISBN 978-3-86705-056-2. [Google Scholar]

- Radman-Livaja, I. Olovne tesere iz Siscije, Les plombs inscrits de Siscia. In Musei Archaeologici Zagrabiensis Catalogi et Monographiae 9; Archaeological Museum: Zagreb, Croatia, 2014; ISBN 978-953-6789-82-5. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, E.A. Socially Embedded Work Practices and Production Organization in the Roman Mediterranean: Beyond Industry Lines. J. Mediterr. Archaeol. 2015, 28, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graßl, H. Zur Textilterminologie auf römischen Bleitäfelchen: Probleme der Lesung und Interpretation. In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD; Gaspa, S., Michel, C., Nosch, M.-L., Eds.; Zea Books: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2017; pp. 250–255. ISBN 978-1-60962-112-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, F. Kleininschriften auf Römischen Bleietiketten als Quellengruppe. Master’s Thesis, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Frere, S.S.; Tomlin, R.S.O. The Roman Inscriptions of Britain, II: Instrumentum Domesticum (in Eight Fascicules) 1990–1995; Sutton Publishing Ltd.: Stroud, UK, 1995; Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- Roman Inscriptions of Britain, 2024. Available online: https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/ (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Fabre, G.; Mayer, M.; Roda, I. Inscriptions Romaines de Catalogne III. Gérone; Boccard: Paris, France, 1991; p. 167. ISBN 84-7929-154-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pi, D.G.; de Llanza, I.R. Une etiqueta de plomo con fitónimos procedente de Mas Vell (Vallmoll, ager Tarraconensis). Espac. Tiempo Forma Ser. II Hist. Antig. 2012, 25, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, L.A.; Bustamante, M.; Bernal, D. Etiquetas comerciales de plomo para textiles en Augusta Emerita. In Purpureae Vestes V, Textiles, Basketry and Dyes in the Ancient Mediterranean World, Proceedings of the Vth International Symposium on Textiles and Dyes in the Ancient Mediterranean World, Montserrat, Spain, 19–22 March 2014; Ortiz, J., Alfaro, C., Turell, L., Martínez, M.J., Eds.; Universitat de València: Valencia, Spain, 2016; pp. 221–237. ISBN 978-84-370-9451-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld, O.; Zangemeister, K.F.W.; von Domaszewski, A. Corpus Inscriptionum Latinum (CIL), Volume XIII, Inscriptiones Trium Galliarum et Germaniarum Latinae; Nabu Press: Charleston, SC, USA, 2013; ISBN 1295113465. [Google Scholar]

- Steyert, A. Nouvelle Histoire de Lyon et des Provinces de Lyonnais-Forez-Beaujolais, Franc-Lyonnais et Dombres; Bernoux et Cumin: Lyon, France, 1895; Volume 1, p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- Schwinden, L. Handel mit Pfeffer und anderen Gewürzen im römischen Trier. Funde Ausgrabungen Bez. Trier. (Aus Arb. Rheinischen Landesmus. Trier) 1983, 15, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinden, L. Römerzeitliche Bleietiketten aus Trier, Zum Handel mit Pfeffer, Arznei und Kork. Trierer Zeitschrift 1985, 48, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feugère, M. Une étiquette inscrite en plomb. In Les Fouilles de la Z.A.C. des Halles à Nîmes (Gard); Monteil, M., Ed.; Bulletin de l’École Antique de Nîmes: Nîmes, France, 1993; pp. 301–303. [Google Scholar]

- Schwinden, L. Zwei römische Bleietiketten mit Graffiti aus Bliesbruck. In Festschrift für Jean Schaub. Études Offertes à Jean Schaub, Blesa 1; Massing, J.M., Petit, J.-P., Eds.; Veröffentlichungen des Europäischen Kulturparks Bliesbruck-Reinheim; Publication du Parc Archeologique Europeen Bliesbruck-Reinheim: Metz, France, 1993; pp. 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Schwinden, L. Asparagus—Römischer Spargel—Ein neues Bleietikett mit Graffiti aus Trier. Funde Ausgrabungen Bez. Trier. (Aus Arb. Rheinischen Landesmus. Trier.) 1994, 26, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božič, D.; Feugère, M. Les instruments de l’écriture. Gallia 2004, 61, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, A.; Hoët-Cauwenberghe, C. Artisanat et commerce: Les étiquettes de plomb inscrites découvertes à Arras (Nemetacum). Rev. Etudes Anciennes 2010, 112, 295–317. [Google Scholar]

- Bats, M. Témoignages d’activités artisanales: Les étiquettes en plomb inscrites des fouilles de l’espace Mangin à Fréjus. In Fréjus Romaine, La Ville et Son Territoire, Agglomérations de Narbonnaise, des Alpes-Maritimes et de Cisalpine à Travers la Recherche Archéologique, Proceedings of the 8ème Colloque Historique de Fréjus, Fréjus, France, 8–10 October 2010; Pasqualini, M., Ed.; Publication de l’APDCA: Antibes, France, 2011; pp. 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Schwinden, L. Vom Ganges an den Rhein. Warenetiketten und Bleiplomben im Fernhandel. In Warenwege—Warenflüsse. Handel, Logistik und Transport am Römischen Niederrhein; Eger, C., Ed.; Nünnerich-Asmus: Oppenheim, Germany, 2018; pp. 423–441. [Google Scholar]

- Graßl, H. Römische Bleietiketten aus Trier: Neue Lesungen und Interpretationen. Z. Papyrol. Epigr. 2021, 219, 289–298. [Google Scholar]

- Frei-Stolba, R. Bleietiketten von Oberwinterthur—Vitudurum. Annu. Rev. Swiss Archaeol. 1984, 7, 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Frei-Stolba, R. Eine Paläographische Bemerkung zu den Bleietiketten aus Oberwinterthur-Vitudurum. Epigraphica 1985, 47, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hampel, A.; Scholz, M. Reiter und ihre Pferdeknechte—Ein neues Bleietikett aus NIDA. In Hessen Archäologie 2012. Jahrbuch für Archäologie und Paläontologie in Hessen; Schallmayer, E., Ed.; hessenARCHÄOLOGIE des Landesamtes für Denkmalpflege Hessen in Kommission bei Theiss: Freiburg, Germany, 2013; pp. 118–121. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, T.; Scholz, M. Decken für die Truppe. Ein Bleietikett aus Groß-Gerau. In Hessen Archäologie 2015. Jahrbuch für Archäologie und Paläontologie in Hessen; Recker, U., Ed.; hessenARCHÄOLOGIE des Landesamtes für Denkmalpflege Hessen in Kommission bei Theiss: Freiburg, Germany, 2015; pp. 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Henrich, P. Bleiplomben und Warenetiketten als Quellen zur Wirtschaftsgeschichte im vicus von Bonn. In Archäologie im Rheinland 2008 (2009); Amt für Bodendenkmalpflege im Rheinland, Landesverband Rheinland, Ed.; Verlag Theiss in Herder: Freiburg, Germany, 2009; pp. 101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Czysz, W. Eine frühkaiserzeitliche Handelsstation an der via Claudia Augusta im Forggensee bei Dietringen, Ldkr. Ostallgäu, Teil I. In Jahrbuch des Historischen Vereins Alt Füssen; Historischer Verein Alt Füssen: Füssen, Germany, 1996; pp. 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Römer-Martijnse, E. Eine frühkaiserzeitliche Handelsstation an der Via Claudia Augusta im Forggensee bei Dietringen, Lkr. Ostallgäu, Teil II—Die beschrifteten Bleietiketten. Jahrbuch des Historischen Vereins Alt Füssen; Historischer Verein Alt Füssen: Füssen, Germany, 1997; pp. 5–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, B. Inschriften auf Metallgegenständen aus dem römischen Vicus Tasgetium (Eschenz TG). Annu. Rev. Swiss Archaeol. 2014, 97, 172–179. [Google Scholar]

- Solin, H. Tabelle plumbee di Concordia. Aquileia Nostra 1977, 48, 145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, P. Bleietiketten mit Warenangaben aus dem Umfeld von Rom. Tyche 1991, 6, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, C. Tre lamellae perforatae da Savazzona-Quistello (Mantova). Epigr. Riv. Ital. Epigr. 1996, 58, 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Buonopane, A. La produzione tessile ad Altino: Le fonti epigrafiche. In Produzione, Merci e Commerci in Altino Preromana e Romana, Atti del Covegno, Venezia 2001, Proceedings of the Conference from Venezia, Venezia, Italy, 12–14 December 2001; Marrone, G.C., Tirelli, M., Eds.; Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2003; pp. 285–297. ISBN 88-7140-244-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bizzarini, L. Quattro laminette plumbee da Altino. Ann. Mus. Civ. Rovereto. Sez. Archeol. Stor. Sci. Nat. 2005, 21, 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Buchi, E.; Buonopane, L. Le etichette plumbee rinvenute a Feltre: Aspetti onomastici, lessicali, economici e tecnici. In I territori della Via Claudia Augusta: Incontri di Archeologia/Leben an der Via Claudia Augusta: Archäologische Beiträge; Ciurletti, G., Pisu, N., Eds.; Tipolit; TEMI: Trento, Italy, 2005; pp. 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Marrone, G.C.; Pettenò, E. Supellex ex plumbo. Laminae Concordienses. Le laminette commerciali da Iulia Concordia. Atti R. Ist. Veneto Sci. Lett. Arti 2010, 168, 43–110. [Google Scholar]

- Annibaletto, M.; Pettenò, E. Laminette plumbee da Iulia Concordia: Alcune riflessioni sui commerci e sulla lana. In La Lana Nella Cisalpina Romana—Economia e Società—Studi in Onore di Stefania Pesavento Mattioli, Atti del Convegno Internazionale, Padova-Verona, Italy, 18–20 Maggio 2011; Busane, M.S., Basso, P., Eds.; Collana Antenor Quaderni 27; Padova University Press: Padova, Italy, 2012; pp. 435–449. ISBN 978-8897385-30-1. [Google Scholar]

- Buonopane, A.; Cresci Marrone, G.; Tirelli, M. Etichette plumbee iscritte e commercio della lana ad Altinum (Italia, regio X). In Instrumenta Inscripta VIII. Plumbum Litteratum. Studia Epigraphica Giovanni Manella Oblata; Baratta, G., Ed.; Scienze e Lettere: Roma, Italy, 2021; pp. 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, R. Fünf Bleietiketten und eine Gussform. Die neuesten Magdalensbergfunde. Anz. Philol.-Hist. Kl. Osterr. Akad. Wiss. 1967, 104, 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, E. Beschriftete Bleitäfelchen. In Proceedings of the 1. Österreichischen Althistorikertreffen am Retzhof/Leibnitz, Retzhof/Leibnitz, Austria, 27–29 May 1983; Publikationen des Instituts für Alte Geschichte und Altertumskunde der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz: Graz, Austria, 1983; Volume 3, pp. 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, E. Ein Bleietikett aus Immurium-Moosham. In Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Institutes in Wien 1968–1971; Austrian Archaeological Institute: Vienna, Austria, 1971; Volume 49, pp. 229–234. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, E. Das Bleitäfelchen mit einem Liebeszauber aus Mautern an der Donau. In Veröffentlichungen des Verbandes österreichischer Geschichtsvereine 25, Proceedings of 16. österreichischen Historikertag in Krems/Donau, Krems/Donau, Austria, 3–7 September 1984; Verband Österreichischer Geschichtsvereine: Vienna, Austria, 1985; pp. 62–65, 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Römer- Martijnse, E. Römerzeitliche Bleietiketten aus Kalsdorf, Steiermark. In Proceedings of the 3. Österreichischen Archäologentages Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria, 3–5 April 1987; Österreichisches Archäologisches Institut: Vienna, Austria, 1989; pp. 171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Farka, C.; Kladnik, O.; Kladnik, S. KG Maria Saal. Fundberichte Osterr. 1989, 28, 212. [Google Scholar]

- Römer-Martijnse, E. Römerzeitliche Bleietiketten aus Kalsdorf, Steiermark. In Denkschriften der Philosophisch-Historischen Klasse 205, 1st ed.; Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften: Vienna, Austria, 1990; ISBN 783700115809. [Google Scholar]

- Alföldy, G. Die Personennamen auf den Bleietiketten von Kalsdorf (Steiermark) in Noricum (Kurzfassung). Specimina Nova 1991, VII/I, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Römer-Martijnse, E. Fullones ululamque cano, non arma virumque (CIL IV 9131). Specimina Nova 1991, VII/I, 111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Römer-Martijnse, E. Blei in der Antike. In Instrumenta Inscripta Latina, das Römische Leben im Spiegel der Kleininschriften; Hainzmann, M., Visy, Z., Eds.; Gradis: Pécs, Hungary, 1991; pp. 46–48/148–151. ISBN 9789636412821. [Google Scholar]

- Römer-Martijnse, E. Auf den Spuren des Textilgewerbes im römischen St. Pölten. In Landeshauptstadt St. Pölten—Archäologische Bausteine; Scherrer, P., Ed.; Sonderschrift, Österreichisches Archäologisches Institut: Vienna, Austria, 1991; pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-3900305116. [Google Scholar]

- Alföldy, G. Die Personennamen auf den Bleietiketten von Kalsdorf (Steiermark) in Noricum. In Sprachen und Schriften des Antiken Mittelmeerraums. Festschrift für Jürgen Untermann zum 65. Geburtstag; Heidermanns, F., Rix, H., Seebold, E., Eds.; Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft: Innsbruck, Austria, 1993; Volume 78, pp. 1–32. ISBN 978-3851246438. [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer, P.; Kronberger, M.; Riegler, Ch.; Risy, R.; Jilek, S.; Zabehlicky, H. Katalogbeitrag I/14 Bleietiketten für Textilien Etikette B. In Florian 2004 Entflammt; Catalogue of the exhibition in Enns-Lorc-St.Florian; Dimt, H., Ed.; Denkmayr: Linz, Austria, 2004; p. 121. ISBN 3-85483-040-8. [Google Scholar]

- Horvat, J. Navport med Jadranom in Donavo, Nova Arheološka Raziskovanja na Vrhniki (Navport Between the Adriatic and the Danube, New Archaeological Research in Vrhnika), Catalogue to the Exhibition, 14 November–6 December 2006, Galerija Cankarjevega Doma; Inštitut za Arheologijo ZRC SAZU: Ljubljana, Slovania, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Graßl, H. Eine littera Claudiana am Magdalensberg. Z. Pap. Epigr. 2005, 153, 241–242. [Google Scholar]

- Dolenz, H. Die Ausgrabungen im Tempelbezirk bei St. Michael am Zollfeld im Jahre 2005. Rudolfinum Jahrb. Landesmus. Kärnten 2005, 2007, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lohner-Urban, U. Untersuchungen im römerzeitlichen Vicus von Kalsdorf bei Graz. Die Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen auf der Parz. 421/1. Baubefunde und Kleinfunde. In Forschungen zur Geschichtlichen Landeskunde der Steiermark 50, Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Archäologie der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz 9; Phoibos Verlag: Vienna, Austria, 2009; ISBN 978-3-85161-018-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lovenjak, M. Four inscribed plates. In The Ljubljanica—A River and Its Past, Catalogue of the Exhibition in National Museum of Slovenia; Turk, P., Istenič, J., Knific, T., Nabergoj, T., Eds.; CIP—Kataložni Zapis o Publikaciji Narodna in Univerzitetna Knjižnica: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2009; pp. 268–271. ISBN 978-961-6169-66-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lamm, S. Die römische Villa von Grünau. Funde und Befunde der Grabungssaisonen 1991, 1992, 2001 und 2002. Ph.D. Thesis, Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz, Graz, Austria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wedenig, R. Kleininschriften auf Keramik- und Bleifunden vom Makartplatz. In Salzburg, Makartplatz 6, Römisches Gewerbe—Stadtpalais—Bankhaus Spängler; Höglinger, P., Ed.; Fundberichte aus Österreich, Materialhefte, Reihe A, Sonderheft 20; Verlag Ferdinand Berger & Söhne GmbH: Horn, Austria, 2012; pp. 50–53. [Google Scholar]