Highlights

The paper’s relevance to the Smart Cities journal lies in its focus on enhancing the resilience and sustainability of critical infrastructure (CI) networks against flooding. It introduces advanced CI network modeling methods to evaluate natural hazards and addresses the gap between analytical methods and practical, multi-sectoral flood measures. The research compiles a comprehensive flood measure catalog through stakeholder interviews and literature review, tailored to various CI sectors. A proof-of-concept study validates the catalog, demonstrating its practical applicability. By considering disruption duration and recovery capability, the study links risk and resilience, contributing to all phases of the disaster risk management cycle. This interdisciplinary approach and practical focus make the study highly pertinent for smart city research and implementation.

What are the main findings?

- Flood Mitigation Measures need to be collected systematically to utilize the benefits of critical infrastructure network models for flood risk management.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- Enhanced Decision-Making and Coordination: Systematically collecting flood mitigation measures enables more informed decision-making and fosters intersectoral coordination, ensuring effective and context-appropriate flood risk management strategies across various CI sectors.

- Improved Resilience and Resource Optimization: This approach enhances the resilience of CI networks to flooding events and optimizes resource allocation by identifying the most cost-effective and efficient mitigation measures, supporting robust policy development and implementation.

Abstract

Critical infrastructure (CI) networks face diverse natural hazards, such as flooding. CI network modeling methods are used to evaluate these hazards, enabling the analysis of cascading effects, flood risk, and potential flood risk-reducing measures. However, there is a lack of linkage between analytical methods and potential multisectoral, structural, and nonstructural measures. This deficiency impedes the development of CI network (CIN) models as robust tools for active flood risk management. CI operators have significant expertise in managing and implementing flooding-related measures within their sectors. The objective of this study is to bridge the gap between the application of CIN modeling and the consideration of flood measures in three steps. The first step is conducting a literature review and CI stakeholder interviews in Central Europe on flood measures. The second step is the culmination of the findings in a comprehensive catalog detailing flood measures tailored to five CI sectors, with a generalized category spanning each phase of the disaster risk management cycle. The third step is the validation of the catalog’s utility in a proof-of-concept study along the Vicht River in Western Germany with a model-based flood risk analysis of five flood measures. The application of the flood measure catalog improves the options available for active and residual flood risk management. Additionally, the CI flood risk modeling approach presented here allows for consideration of disruption duration and recovery capability, thus linking the concept of risk and resilience.

1. Introduction

Infrastructure and organizations supplying essential services to society are described as critical infrastructure (CI) or critical entities. In an environment with a changing climate, extreme weather events cause more frequent or extreme flooding events that disrupt CI [1]. CIs are organized in sectors such as electricity, information, and communication technology (ICT), freshwater supply, sewage water treatment, and gas supply. These form networks through their dependencies [2]. Disruptions to individual CI elements caused by flooding cascade through these dependencies both within CI sectors and outside these sectors [3]. These effects are referred to as cascading effects and are characteristic of the arrangement of CI sectors in networks or critical infrastructure networks (CIN).

A generalized flood risk management (FRM) workflow consists of three elements: analysis, assessment, and action-taking [4]. In this framework, the flood risk is defined as the product of the flood consequences as well as the probability of their occurrence [5]. The flood consequences can include several dimensions of consequences such as economic damages, the consequences for the population affected or endangered, or the consequences for the critical infrastructure services [4]. To analyze and assess the risk to CIN caused by flooding and other natural hazards, network modeling techniques are utilized to assess the highly complex interactions in closely webbed networks [6,7,8]. Depending on their design, modeling approaches allow consideration of the characteristics of individual CI sectors, of direct disruptions caused by flooding, and of indirect disruptions caused within a sector (sectoral) and across multiple sectors (trans-sectoral). These effects are referred to as cascading effects and can be quantified as time of disruption per person, as demonstrated in the study conducted by [9,10]. A range of network modeling approaches are available, and a handful of them also focus on flood consequences, but these modeling approaches rarely concentrate on the testing and implementation of flood measures.

After determining the flood risk for the CI, an assessment is conducted. This requires public or political representatives to decide on the acceptance or refusal of a current flood risk situation. Acceptance involves dealing with residual flood risk and defining preparation, response, and recovery measures to address the remaining risk. The refusal of flood risk situations leads to the development of prevention and mitigation measures to invoke changes [11]. Case studies analyzing flood risk for CIN often overlook potential measures or fail to assess the potential benefits of measures in their modeling frameworks [12]. CIN, by their definition, overarch different CI sectors; thus, knowledge of the specific CI sectors is necessary in order to include appropriate measures. Another challenge is that conventional flood risk adaptation does not consider measures embedded in an interdependent supply network of CI, which necessitates a systematic understanding of potential measures. Additionally, input and validation data are scarce and limit not only the analysis but also the inclusion of potential measures [13,14].

Measures vary according to each stage of the disaster risk reduction (DRR) management cycle. In the context of this work and considering CI as a thematic background, five stages of the DRR cycle are defined, in accordance with the studies conducted by [15,16]. These stages define time periods in the progression of actions necessary after a disaster event or, as defined here, impact. The next stage is defined as response, describing the actions or strategies that respond and adapt immediately to the adverse impacts of an event. Subsequently, the stage of recovery and rehabilitation is highlighted, focusing on returning CI services to acceptable and constant conditions for end users and chain partners. The stage of prevention and mitigation progresses to increase resistance, adapt to the impact, or avert it in other ways. The final stage before closing the DRR management cycle describes the preparation during which all measures are taken in the immediate anticipation of an event (cf. Figure 1). Further, all measures in the DRR management cycle for flooding are referred to as flood measures.

Figure 1.

Disaster risk management cycle as suggested by [15].

The consideration of measures is what differentiates the term risk from the term resilience. Ref. [17] defines resilience as the “capacity of a system to return to desired conditions after disturbance”, which not only includes the capacity itself but also the time until a system is returned to a desired state. This definition of resilience is applied in this manuscript, as also applied by [18]. The Sendai Framework’s definition states that systems are able to react more resiliently to disruptions if they are equipped to “build back better” after disruptions [19].

Cataloging of flood measures has been frequently used by homeowners at the property level to increase the resilience of properties [20,21]. Previous events and the experiences of CI operators and stakeholders can also be used to catalog measures taken. Ref. [22] identified measures for a case study in a participatory environment with CI operators and compared the numbers of people and duration of disruption with and without measures. Sector-specific associations, such as the German Association for Water, Wastewater and Waste (DWA) and the German Technical and Scientific Association for Gas and Water (DVGW), take a normative approach to measure collection by defining technical recommendations to manage flood risk for the operators of their supply networks. The study by [23] concentrated on seven measures across three CI sectors to increase resilience with respect to sea level rise. However, conventional measures, such as linear protection structures, have been tested in the hydraulic domain and chosen based on their effect on CI networks [24]. Conventional flood protection, mitigation, or recovery measures not considering CI—as gathered in other studies such as [25,26]—are not the focus of this study. Flood measures have been collected systematically previously in research manuscripts and practice, but what is currently missing is a collection of flood measures specific to CI.

In summary, the current literature reveals a significant gap between FRM and CI, indicating a need for closer integration. CIN modeling methods are inadequately aligned with the objective of evaluating flood measures. Additionally, there is a lack of systematic collection of flood measures across CI sectors for this purpose.

To address these gaps, it is essential to establish a comprehensive integration between FRM and CI, considering both technical and organizational aspects. The current state-of-the-art risk-based evaluation of measures must be expanded to incorporate those from the CI domain. This requires the structural definition of measures, categorized by CI sectors and specified by their implementation timelines.

In the present study, the focus is on sectors with a high level of physical and logical interdependencies, such as electricity, ICT, freshwater supply, sewage water treatment, and gas supply. These are referred to as primary sectors because of their high potential to disrupt other sectors. Secondary sectors, which are defined by their characteristics of mostly relying on incoming physical and logistical dependencies and severity for the civil population, are excluded (e.g., health or public administration). Additionally, the transportation sector and linear structures of the previously highlighted sectors, such as pipes, cables, and road networks, were not specifically considered.

The present work has already provided an introduction covering the thematic background, current knowledge gaps, and the first part of a literature study on critical infrastructure protection and adaptation measures. The objective of this manuscript to bridge the gap between CIN modeling for FRM and the consideration of flood risk-reducing measures is addressed in two sections: Section 2 describes the systematic collection of flood measures through a second, systematic part of the literature review, expert interviews, and a third part of the literature study based on the input of the interviews. The findings of this section funnel into a measure catalog for each CI sector, as well as a generalized category, and for every stage of the DRR management cycle. In the following section, a flood risk management approach including CIN modeling methods is introduced to enable a risk-based evaluation of potential flood measures. Subsequently, a case study is presented in Section 4 for the low-mountain range stream Vicht near Stolberg, Germany. A flood risk analysis is conducted utilizing a CIN model, together with an assessment of the effectiveness of measures taken from the catalog to reduce flood risk. In the subsequent section, the findings of this study are discussed, and an outlook is provided for potential future developments and challenges. Finally, the presented work is concluded.

2. Flood Measures for Critical Infrastructure Networks

Flood measures specific to critical infrastructures are cataloged in this section using literature and expert interviews as sources. The methodology used to conduct the interviews and the derivation of the catalog are briefly described. Generalized CI measures are deducted from sector-specific CI measures with equivalent approaches. Subsequently, the results for each CI sector are clarified individually.

2.1. Methodology for the Derivation of a Measure Catalog

The catalog, literature review, and interviews are structured in accordance with the stages of the DRR management cycle above: impact, response, recovery and rehabilitation, prevention and mitigation, and preparation (cf. Figure 1). The hierarchical structure of each CI sector and the idealized elements are outlined to fully understand the impact and subsequent steps of the DRR management cycle. The measures in each of the CI sectors are identified in a three-step process: (1) systematic literature study on CI sector elements and hierarchical structure; (2) validation and complementation of the hierarchy and measures in the interviews; (3) complementation through a second literature review.

The first step, an initial systematic literature study, is carried out to identify CI elements and hierarchical structures across primary CI sectors. The systematic literature review examined the results for the term ‘critical infrastructure hierarchy’ and was complemented by the terms ‘measures’, ‘natural hazards’, and ‘flooding’ on a scientific search engine. In a subsequent step, the ‘electricity’, ‘ICT’, ‘freshwater’, ‘gas’, and ‘wastewater’ sectors were added as a word to the search term. These sectors were selected for further analysis due to their alignment with the selected modeling method from [10]. Relevant literature defining CI sector hierarchies and potential measures was considered prior to conducting interviews. This included publications and reports on sectoral damage and adaptation studies [27,28,29], multi-sectoral studies on network and protection measures [30,31], and recommendations from public authorities [15,32,33,34].

In the second step, interviews are conducted to validate the findings from the first step and complement the understanding of the hierarchical network systems for five CI sectors (electricity, ICT, freshwater, gas, and wastewater). Once the network system has been validated with the interviewees, potential flood risk reduction measures or literature pointing towards additional measures are identified. The interviewees are international experts and operators in the field of CI operations and flood risk management in Central Europe. Therefore, the measures collected are most applicable in industrialized environments. Table 1 provides an overview of the occupations of the interviewees and asterisks are used to indicate who has practical experience in managing flooding. The interview methodology follows [35] and is integrated into the presented study following the approach taken by [36]. The interviewees are presented with four questions structuring the conversation: (1) Which elements of the hierarchy in the CI sector are vulnerable to flooding? (2) What is the structure of the critical infrastructure sector? (3) Which options are available for a specific sector as flood management measures? (4) Is it possible to quantify the effects of these measures? As an outcome of the interviews, a hierarchical network structure is presented for each sector along with the measures that were identified and described. Other statements made by interviewees are considered briefly during the discussion of this manuscript (cf. Section 4.).

Table 1.

Interview partners for the compilation of flood risk measures specific to critical infrastructures. The X indicates the affiliation with certain sectors.

In the third step of compiling a catalog of measures, additional measures were gathered based on the literature recommendations from the interviewees. This literature study focused on guidelines and reports from critical infrastructure operators [37,38,39].

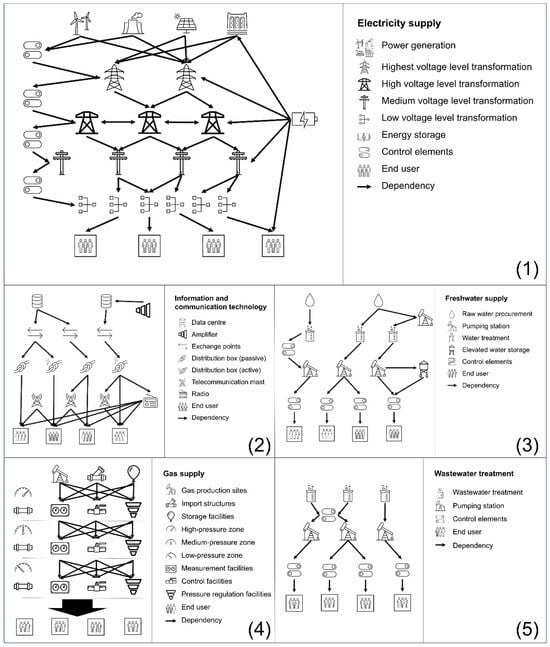

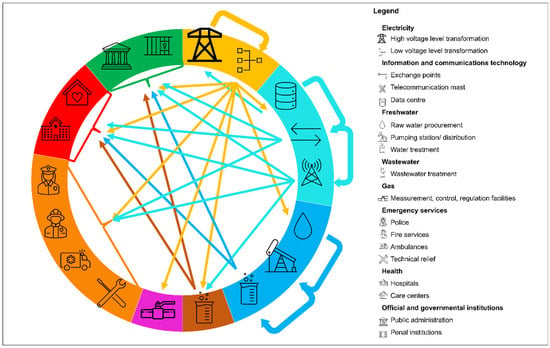

As a result of all three steps outlined above, a hierarchical structure for each sector is identified in Figure 2. Another result is the measure catalog presented in Table 2 showing the possible impacts as well as the measures identified throughout the literature study. The catalog does not describe the continuous development of the measures catalog from steps 1 to 3 in order to keep the results section clear and concise. A range of measures or measure types occurs in every sector and is thus summarized as generalized measures in the following Section 2.2. For each individual sector, a hierarchical system is introduced and one measure from Table 2 is focused on as an example.

Figure 2.

Hierarchy of network elements for electricity supply (1), information and communication technology (2), freshwater supply (3), gas supply (4), and wastewater treatment (5).

Table 2.

(A). Catalog of flood risk measures for a range of CI sectors and a generalized type. (B). Catalog of flood risk measures for a range of CI sectors and a generalized type.

The objective of this study is not to replicate the hierarchical structure and granularity of each CI sector as precisely as possible but to do so at the level of detail necessary to comprehend the influence of the measures on the network as a whole. The knowledge of CI operators plays a pivotal role in understanding, safeguarding, and managing CI assets during extreme events. Therefore, interviews with CI operators are conducted to confirm and complement the hierarchical structures across various CI sectors and the potential impacts on the relevant CI network elements, and to identify measures for each step of the DRR management cycle.

2.2. Generalized Measures

Generalized measures are introduced for each stage of the DRR management cycle. Before elaborating on the DRR management stages that link to the measures, it is important to understand the dynamics of the flood impacts:

Impact: Across all sectors, inundations disrupt punctual assets and impact CI services. However, the impacts on electricity and wastewater treatment facilities are exceptional because these facilities present immediate health risks when impacted. Most operators do not focus on damage to linear structures for risk management or identification of potential measures during the interview.

Response: Network replacement units (NRU) are of the highest importance to all sectors and play a key role in the response to flooding events. NRUs refer to the different types of services that they replace (e.g., generators, pumps, or ICT components). In addition to the availability of NRUs, sufficient availability of fuel and the possibility of connecting NRUs to CI structures are important to all sectors. The NRUs significantly reduce the response and recovery times. Regional social networks of critical infrastructure operators inform each other about the availability and needs of the NRUs’ systems and fuel reserves. Another point mentioned by experts from all sectors is that technical maintenance teams gather at predefined locations during disruptive events to receive and follow up on action and priority lists. The availability of a priority list of measures to be taken by each CI operator during the response phase is connected to the previous two measures.

Recovery and Rehabilitation: The last point referring to priority lists of the response phase mentioned above also applies to the recovery and rehabilitation phase. In addition, the generalized measures in this stage refer to the restoration of the CIN networks’ functionality and the dismantling of the NRU.

Prevention and Mitigation: The first measure in this stage, valid for all CI sectors, is to not build in flood-prone areas in the first place and not build linear structures (cables, pipes, roads, etc.) parallel to river bodies. The second generalized measure is to elevate or protect punctual CI assets to prevent impacts from inundation. Both measures can also be assigned to the conventional flood measures. The third generalized measure is more network-specific and refers to higher redundancy in the CI network by increasing the number of connections to other network islands to better compensate for service disruptions caused by high-level impacts.

Preparation: All CI stakeholders and operators highlighted the importance of inclusion in crisis management committees during the preparation phase. Close collaboration with meteorological services and frequent scanning of flood information systems are also relevant. Another part of the preparedness stage for all CI operators is to organize sufficient NRUs and to make arrangements with service providers required during crisis response and recovery (security firms, technical contractors for repair services, administrators of permits for maintenance vehicles, etc.). A more technical measure that overarches all operators is to organize the availability and operability of mobile flood defense systems and sandbags. For sandbags, it is important to store sufficient bags and sand and organize suitable placement on the CI operator properties. Raising awareness of prevention and mitigation measures at the individual and household levels of CI employees is another measure that increases the availability of these employees during extreme events.

2.3. Hierarchical Structures, Flood Impacts, and Exemplary Measures of Critical Infrastructure Sectors

The following sub-section includes a brief explanation of the hierarchical structure of the CI sectors considered (cf. Figure 2) as well as a description of the impact dynamics that occur during a flood. Subsequently, one example of a measure is given that is specific to the CI sector. The complete extent of the measures per sector can be taken from Table 2(A,B). Due to the limited extent of this manuscript, the results for the gas sector will not be further discussed but are still present in Figure 2 and Table 2(B).

2.3.1. Electricity Sector

The electricity supply network consists of several levels of electricity distribution or voltage levels which are connected through transformation stations, also called substations, transformer stations, or on the lowest level street cabinets (cf. Figure 2(1)). Between the voltage levels are the control elements that manage the electricity streams and ensure functionality. These can be operations centered on the highest voltage levels down to remote shutdown devices for the low-voltage level. Energy storage and power generation can be connected at all voltage levels but will not be considered in detail in this study. The specialty of the electricity network is that, from the lowest level, an electrical current, and thus also a dependency, can be directed to the upper transformation levels. Other modeling approaches differentiate the electricity network with a higher granularity, e.g., [40].

Impact: Electricity components and water are incompatible because of the high conductivity of water. The presence of water can compromise electrical insulation and increase the risk of electrical accidents at all levels of transformation and control elements.

In addition to the general measures already listed, electricity suppliers must release the threatened transformer stations from the network as a response measure. On the one hand, this prevents health risks through electric shocks; on the other hand, fault currents in installations cannot be passed on to other networks in parallel routing.

2.3.2. Information and Communication Technology Sector

The hierarchical system of the ICT sector is understood in the context of this study as follows (see Figure 2(2)). ICT services can be divided into mobile network services and cable- or fiber-based Internet and telephone services. Radio stations are also regarded as an important aspect of the ICT sector. The highest punctual assets are the data centers connected to each other through glass fiber connections and amplifiers that maintain signal strength. Cable and fiber networks connect data centers to exchange points, and exchange points with distribution boxes. Distribution boxes can be classified as active (electrically charged) and passive (not electrically charged). From the distribution boxes, telecommunication masts or antennas are supplied; these provide mobile networks to end users. At the same time, distribution boxes also supply end users with cable- or fiber-based internet and telephones.

Impact: Most components mentioned in the ICT sector hierarchy rely on electricity and are thus easily impacted by inundation or disruption in the electricity sector. Only for passive distribution boxes is the impact more related to debris as a side effect of inundation. In addition, telecommunication towers can be affected because they usually need a connection to the wired system and are also active-running currents.

For recovery efforts, active distribution boxes must be repaired using spare parts, which takes a day if sufficient staff and materials are available. Cleaning is sufficient for passive distribution boxes.

2.3.3. Freshwater Supply

Freshwater supply sector assets are arranged in three layers. The first layer is raw water procurement, which can be well facilities, surface water intakes, or desalination plants. The second layer is the water treatment level, usually represented by waterworks. Under specific conditions, the first and second layers may need to be connected via pumping stations. The third layer represents the water distribution to end users via pumping stations and control elements. In some surroundings, elevated water storage connects end users (cf. Figure 2(3)).

Impact: Flooding affects all layers of the freshwater supply system. For the water procurement well, facilities near water bodies (shore filtrate facilities) are damaged for an indefinite period by the contamination of floodwaters. Water treatment facilities are impacted not only by the water but also by the entry of pollutants and contaminants that the treatment plant cannot remove. Damaged or disrupted pumping stations cause a pressure drop in the supply lines, cutting the supply for end users. A pressure drop also leads to the entry of foreign substances from outside into the pipeline system.

One potential measure to prevent disruption in the freshwater supply sector is to detach all assets from dependency on the ICT sector. All assets can be operable using mobile networks, but this should be optional. Staff expertise and technical design should ensure that the supply system can be operated without ICT functionality.

2.3.4. Wastewater Treatment

The structure of the wastewater treatment system consists of three layers, with the water treatment facility at the top level. Wastewater treatment facilities rely on the functionality of a multitude of pumps that transport sewage water from households to end users (cf. Figure 2(5)). Between these levels, control elements are placed that connect the levels of treatment facilities, pumping stations, and end users.

Owing to the proximity of water treatment facilities to water bodies, backwater quickly enters the treatment facilities where electrical components are damaged, and the different stages of the treatment are biologically or physically damaged. Pumping stations that transfer wastewater fail as a result of direct impact or power failure. This causes wastewater reservoirs to overfill and float, thereby causing health issues. However, it should be noted that the wastewater volume can decrease by 50% in affected areas. The control elements often depend on the power and ICT supply, and thus can fail indirectly.

One preparedness measure specific to the wastewater sector is the closing of backflow preventers, which of course also requires previous installation at the prevention stage as well as the opening of the backflow preventers as a response immediately after the flooding.

3. Risk-Based Evaluation of Flood Measures for Critical Infrastructures

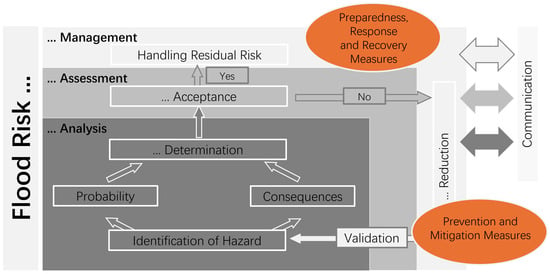

The presented section shows a FRM process that considers CIN to evaluate flood measures specific to CI. Two manuscripts deliver the basis for the risk-based evaluations of previously identified flood measures. One manuscript outlines the integration of CIN in FRM [4], and the second manuscript defines the modeling approach of CIN for flood risk analysis [11].

3.1. Consideration of Flood Measures in Flood Risk Management

Flood risk management is grounded in a comprehensive flood risk analysis (FRA) as visualized in Figure 3. This analysis consists of identifying flood-prone areas and combining probabilities for recurrence intervals or failure probabilities with the potential consequences of flooding. The FRA uses these values to determine the flood risk for the current situation. The decision to accept or reject the current flood risk necessitates identifying appropriate types of measures along the DRR management cycle (cf. Figure 1). As described in the previous section, these measures were identified in this manuscript through a participatory approach. The FRA describing the current situation is then also used to test the effectiveness of various flood measures.

Figure 3.

Flood measures placement in the process of flood risk management [4].

3.2. Model-Based Evaluation of Flood Measures for Critical Infrastructures

The comparison of the effectiveness of flood measures requires quantification of the flood risk, which is especially challenging with a focus on critical infrastructure services. In the presented case study, a topology-based network modeling approach that has been defined elaborately previously by [10] is used to analyze the consequences of flooding on multisectoral CIN. The CIN modeling approach is connected to the ProMaIDes framework, which combines hydraulic and consequence modeling capabilities, as well as probabilistics, to derive flood risk at a catchment-based level [11].

The modeling approach utilizes three types of network elements to represent CI networks: point elements, polygon elements, and connector elements. Point elements represent CI structures using attributes and are assigned to sectors and levels within their sector. The threshold attribute of the point element determines the water depth, which causes complete failure of the point element, and the recovery time attribute defines the time a point element is disrupted after threshold values are crossed. The connector elements link the point and polygon elements. Moreover, the connector elements transmit disruptions to the interconnected elements. Polygon elements establish the spatial scope of their connections with point elements, either entirely or partially. Furthermore, the polygon definition is based on the number of end users or consumers it serves with a particular service.

The three types of elements and their attributes allow the modification of the CIN model in its current state to represent a range of measures. For example, accelerated response measures can be represented by a decreased recovery time of point elements. Mobile flood protection walls and elevation of critical components can be represented in the model by increasing the threshold value. Additional redundancies or emergency structures can be represented by newly added point and connector elements. Therefore, the chosen modeling approach enables the quantification of a wide range of measures previously identified in Table 2.

The quantifiable output of the modeling approach delivers Pdis,sec [people], the area and number of disrupted people per element i and sector sec. The recovery time of the center element indicates the time of disruption ti [d] for the other network elements. The multiplication of Pdis,sec and tsec for all end-user elements per sector e results in the population time per sector TPop [people × d]; see also [9].

Tpop is used in combination with the hydrological probability phyd per return period scenario k to derive the risk as a decision-making unit. The sum of all products of TPop and phyd per return period scenario k results in the risk of consequences for CI RCI [people × d/a]:

After determining the flood risk for the current state, measures can be introduced into the CIN model, as previously described. The flood risk for the current state can then be compared with the flood risk under consideration of measures to determine the potential benefit of measures and deliver a basis for more objective decision-making for the implementation of measures [4].

4. Case Study—Potential of Flood Measures in the Vicht Catchment

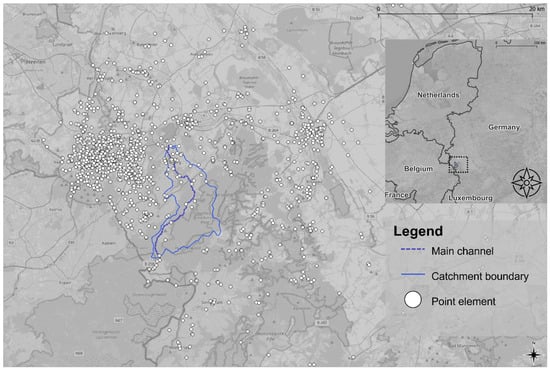

In this section, a proof-of-concept is introduced for the application of the catalog for CI flood measures in combination with a flood risk management model workflow. The focus of the study encompasses the catchment area of Vichtbach or Vicht, which covers a region of approximately 68 km2 and features a medium-sized mountain stream with a length of 23 km (cf. Figure 4). The Vicht’s source is close to the Belgian border and the main channel passes through five localities before flowing through the town center of Stolberg and finally joining the Inde River.

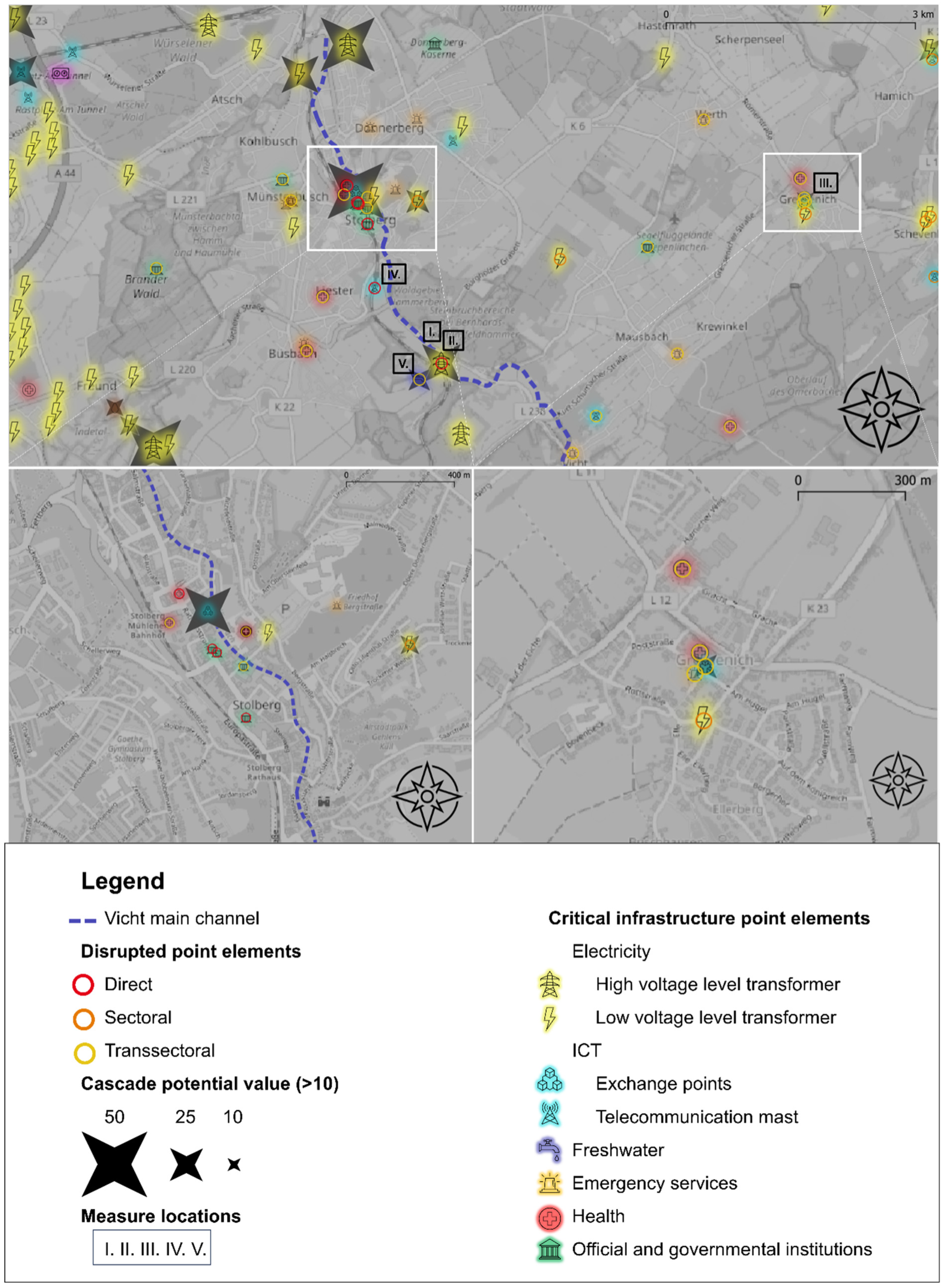

Figure 4.

Catchment boundary for the area of investigation at the western border of Germany, next to Belgium and the Netherlands. The point elements represent CI assets that are represented in the critical infrastructure network model.

The case study area was chosen along a river body that had significant impacts during flooding events in Western Europe in 2021. Comparable studies used the flooding in 2021 as a benchmark for what-if analyses, such as [41]. At the same time, the catchment offers a testing ground of a relatively small size and is thus comprehendible. The combination of recent flooding and good news coverage, in combination with a small catchment area, allows for good checks of plausibility. Additionally, a quality check of the availability of OSM data coverage showed good results [42]. The electricity and telecommunications sectors were represented by a sufficient number and type of point elements to form a hierarchical system.

This section consists of the introduction of the network model, its elements, and their associated attributes, as well as a hydraulic model including hydrological probabilities. Consecutively, the network model and hydraulic model are used to test potential measures. The free software ProMaIDes, version 0_10 vc, is used for hydraulic modeling, CI consequence modeling, and derivation of the risk, as introduced in Section 1 and by [43].

4.1. Critical Infrastructure Network Model

The network model for this proof-of-concept overarches the catchment area by at least 30 km to ensure that cascading effects are not cut by the boundary of the hydrological catchment boundary (cf. Figure 4). Only structures within Germany are considered because sectors and sector-level assets in the catchment are assumed to not have major cross-country dependencies. All point elements shown in Figure 4 are derived from the OSM database [42]. The point elements, as well as the polygon and connector elements, are differentiated for every sector-level asset, as shown in Table 3. Point-specific attributes such as threshold and repair time were derived for point elements from a range of sources such as [44,45]. Freshwater, wastewater, and gas supply are not represented in the model as a hierarchical system, as introduced in Section 2, because the data density was not sufficient. The polygon elements are derived using the closest distance method (Voronoi polygons) for every point element necessary as done by [6,10]. In combination with population density data, a number of end users are associated with each polygon element [46]. The connector elements are visualized in Figure 5 showing the dependencies of every point element per sector and level in that sector as identified during the interviews in Section 2. The dependencies are derived from a common infrastructure grid operated in Germany. Dependencies from the electricity, ICT, and wastewater sectors apply to all elements of the secondary CI sectors (emergency services, health, and official and governmental institutions).

Table 3.

Represented sectors and sector-level assets, number of CI network elements, and associated model attributes. The bottom line represents the total number of CI elements and for the element attributes the average or mean value for all sectors.

Figure 5.

Connector elements show which point element types have dependencies on each other in the Vicht case study. Trans-sectoral connector elements are represented by arrows inside the circle and sectoral connector elements are represented by arrows outside the circle.

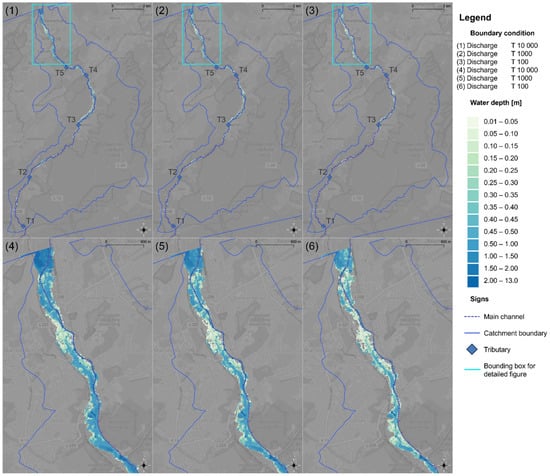

4.2. Hydraulic Model: Input and Output

Another component for the flood risk analysis is the hydraulic model, which consists of a 1D part for the Vicht main channel and 2D rasters covering the entire catchment. The purpose of the hydraulic model is to derive inundations and velocity 2D information and superpose them with the CI network. The results of the hydraulic model additionally allow the assessment of the time course of a flood event. As an input for the hydraulic model, a digital elevation model with 10 m resolution is used. The 1D river model consists of 99 profiles with a width of 50 m and a distance of ~230 m in between profiles. For the hydraulic boundary, a synthetic discharge was used as a T100 event, and based on a logarithmic distribution, T1000 and T10,000 discharges are derived (cf. Table 4). No measurements were used to derive the hydraulic boundary since the differentiation from fluvial and pluvial effects of historic events was not possible. Therefore, the hydraulic boundary and the return periods are not the most reliable because a long set of measurements is necessary in order to derive reliable return periods. However, the purpose of this proof-of-concept is not to derive the most accurate values for return periods but to show the risk-based approach of CI analysis and measure planning by calculating water depths associated with different probabilities of occurrences (cf. Table 4). Therefore, a wide range of return periods is essential. The hydraulic model uses discharges as boundary conditions, which were added to the main channel of the Vicht in five tributary inflows (cf. Figure 6 (1–3)). A detailed view of the city of Stolberg shows the inundated areas in Figure 6 (4–6). The values of the discharge boundary conditions for each tributary are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Boundary condition discharge for the hydraulic model per tributary.

Figure 6.

Water depth from the Vicht derived from the hydraulic model for three return periods; (1–3) show the result for the entire catchment; (4–6) show the result for the detailed view of the city center of Stolberg. T1–T5 describe the tributaries entering the main channel.

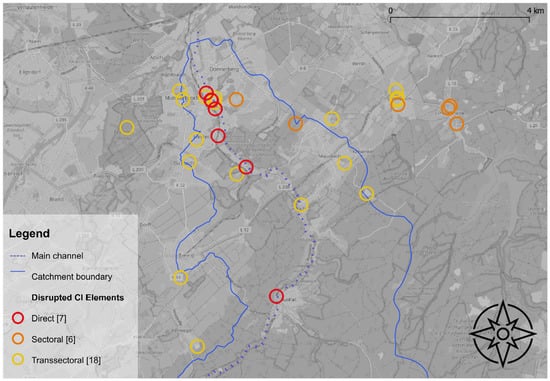

4.3. Current Risk

The combination of the hydraulic model and the CI network model delivers an analysis of the current flood risk situation for the area of interest. Figure 7 shows the directly disrupted CI point elements in the catchment area for a T10,000 flood event and indirect sectoral and indirect trans-sectoral failures outside the catchment area. The results for a T10,000 yearly flood event help identify a worst-case scenario. Table 5 shows the total number of impacted CI point elements and each failure type for every return period. Another output is the yearly risk of people disrupted from critical infrastructure services per year RCI, pop as well as the population time disruption from the CI services RCI. Table 4 shows RCI,pop, and RCI for each sector in the current state. For comprehension, the sectors of emergency services, hospitals, and care centers have been cumulated to health, governmental institutions, and penal facilities to social. The method for deriving the RCI has been introduced previously (cf. Section 1). The most severely affected sector according to RCI,pop, and RCI is the health sector, which is also a result of the bundling of specific sector services (four different emergency services, hospitals, and care centers).

Figure 7.

Disrupted critical infrastructure elements based on a T10,000 flood event in the Vicht catchment.

Table 5.

Impacted CI point elements for each return period and failure type.

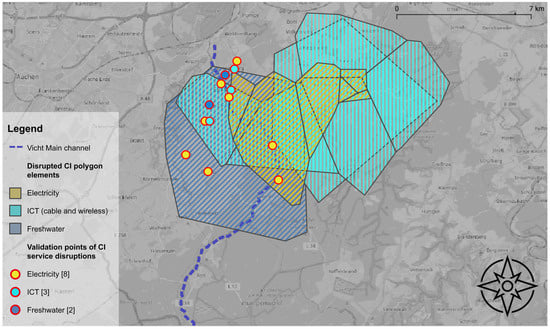

In addition to the quantitative results of the model, spatial extents of CI disruptions are highlighted as shown in Figure 8, where the CI service disruptions for the electricity, ICT, and freshwater sectors are shown through the CI polygon elements. A T1000 event is chosen for Figure 8 as the medium-intensity scenario of the three available ones, although, as indicated previously, the discharges are not empirical. The model results show that in parts of the city center of Stolberg, all three mentioned sectors are disrupted simultaneously. The ICT polygons are shown double-layered because they refer to wireless and cable-based internet.

Figure 8.

CI polygon elements were disrupted through the T1000 flood event for the electricity, ICT, and freshwater sectors. Points indicate locations and sectors where a disruption was indicated in social media posts.

Owing to the limited availability of integrated datasets for validation, only anecdotal validation for the model results is executed. Posts in a Stolberg-focused social media group were analyzed during the flooding in July 2021 [47]. The hydraulic boundary does not fit the flooding in 2021 but can give an impression of the sectors that are involved. Posts that commented on a disrupted CI service and a specific location are shown in Figure 8 as validation points. Most posts were concentrated in the three CI sectors previously mentioned. The comparison with the model results confirms the accuracy of the modeling results in seven of 13 validation points. However, the validation can only confirm that a disruption occurred, and not the duration of the disruption.

4.4. Testing Measure for Effectiveness

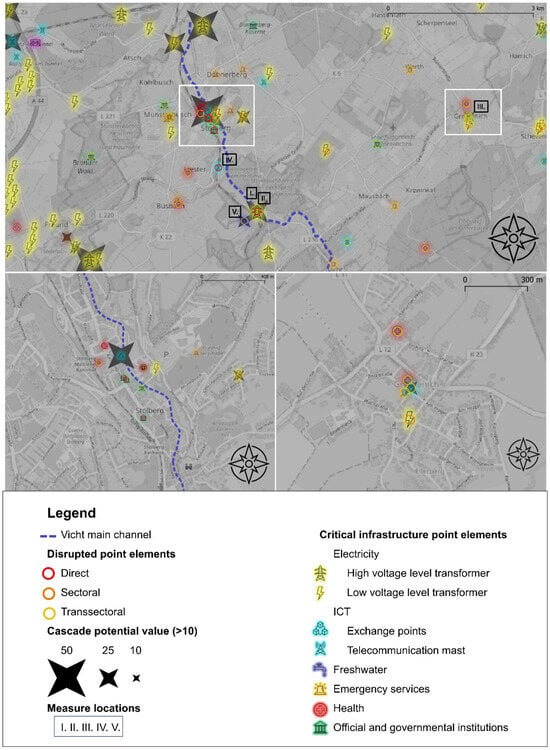

In this part of the case study, the flood measure catalog was utilized to identify potential measures. The network model in combination with the hydraulic model provides evidence about the potential benefits of the measures. Flood measures are necessary to improve the current situation, as analyzed in Section 3.2, and to make a shift from mere flood risk analysis towards flood risk management (cf. Section 1). Some of the measures collected can be tested in the CIN model environment (cf. Section 3.2) and compared to each other for decision-makers to choose the most suitable solutions. Table 2 is used to determine the measures that could be considered for the case study. In addition to the table, the Cascade Potential Value (CPV) is used to highlight which CI point elements have high potential for measures to be effective. The CPV of each point element determines the number of dependent CI point elements [10]. A high CPV indicates that the failure of a point disperses further and causes indirect sectoral or trans-sectoral disruptions. A high CPV and a direct disruption highlight the necessity to check for measures. Figure 9 shows a spatial overview of these points, as well as the locations chosen for five potential measures (Measure I–V) from three different sectors. Table 6 describes the measures that have been considered and links each measure to the cell from which they originate in Table 2.

Figure 9.

View of a section of the catchment area of the Vicht, including the CI point elements, cascade potential values, disruptions, and locations of considered measures.

Table 6.

Measures considered in the benefit analysis of the CIN model framework.

Measure I considers a shorter recovery time of the electricity substation owing to the storage of spare transformers. Measure II applies to the same substation but prevents disruptions by raising the disruption threshold value by elevating the active components and installing watertight cable entries. Measure III refers to an ICT exchange point that is additionally connected to an electricity source in another catchment. It is well noted that flooding within the neighboring catchment is not analyzed, and thus Measure III inherits an additional unknown risk. Measure IV concerns a directly disrupted telecommunication mast, which is elevated. Measure V involves the acquisition of network replacement units that have the potential to decrease the disruption time as long as operating resources, such as fuel, are available, which is usually 48 h. Measure I and V both cause the reduction of recovery time but with different mechanisms. Whereas Measure I is effective due to the fast replacement of damaged components in a network element, Measure II uses a temporary measure to replace a broken network element temporarily.

The inclusion of the scenarios in the modeling framework results in numbers for the risk of disrupted people RCI,Pop, and the risk for population time disruption RCI as introduced in Section 1. RCI,Pop is a simplified version of RCI that focuses solely on the cumulative risk to the number of people affected, without considering their associated disruption time. Table 7 summarizes the risk for each sector or cluster and shows the effective difference in the current situation caused by the specific measures. The results show that Measure I and II are most effective in decreasing the risk. However, the remaining Measures III, IV, and V can also help to reduce the sector-specific risk.

Table 7.

Risk of population disruption and risk of population time of disruption from CI services per year through flooding in the Vicht catchment for the current situation and with consideration of flood measures for CI.

5. Discussion & Outlook

The present study is separated into two parts. In part one, a literature study and interviews with CI stakeholders and experts are used to derive a catalog of potential flood measures. In part two, a case study showcases how measures are included in a network model. Both parts are discussed, and an outlook is provided in the following section. The measures collected were not quantified during the interview with regard to the potential of increasing the threshold of resistance to flood water depth or recovery time. The interview partners indicated that this remains a highly specific attribute. It is recommended that a systematic collection of measures, including quantification of their attributes, be continued to reduce this uncertainty. Additionally, it is recommended to represent the temporal progression of the setup and dismantling of measures in the CIN modeling approach in more detail, for example, in a system response function as done by [9,48]. The basis for such temporal progression could be reports written by CI operators or public administration on previous flood events, such as the flood chronic from the drainage and wastewater treatment enterprise of Dresden, Germany [49].

During interviews, it was frequently mentioned that the acquisition of funding for flood measures remains a challenge. Following the principle that ‘there is no glory in prevention’, there is no reward for a more robust and resilient CI service. It has even been stated for some CI sectors in Germany that investments in disaster resilience cannot be passed on to consumer prices. However, ensuring the stability of CI services also during extreme events has been shown to be extremely important due to cascading effects and costs [50]. Therefore, the World Bank asks for the risk and potential cost to be understood before disasters occur [51]. The present study shows how to quantify the effectiveness of flood measures for CI and provides a basis for the acquisition of funding that supports policy- and decision-makers in the CI domain.

Very few studies combine a hierarchical system for more than two CI sectors [6,52]. In this case study, the representation of the freshwater, wastewater, and gas sectors was not possible in a hierarchical system due to data availability. Therefore, it is recommended to collect and provide CIN data from multiple sectors. Additionally, it is recommended to extend the presented case study by comparing the potential costs of the suggested measures and improve the linkage to funding the implementation stage and support the decision making. Another addition worth considering for future case studies is testing the quantifiable risk reduction that is achievable by combining measures in the model. An overlap of areas of impact could result in lower effectiveness than the sum of individual measures might suggest. Conversely, particularly broad measures could be identified that, despite being combined in the model representation, approach the sum of their individual results.

Nevertheless, the case study introduces a range of uncertainties and assumptions that should be clearly communicated to decision-makers to ensure they understand the quality of the results when implementing measures. These assumptions and uncertainties have an influence on the model output which needs to be communicated to the recipients of the model outcome [14]. As a part of a disclaimer of model outputs, it is recommended to execute sensitivity analyses to assess the model quality. Although these inaccuracies exist, the method still provides a strong foundation for stakeholders to make informed decisions about which measures could impact these complex systems.

For the investigated area, only publicly available data and information were used. Validation of the network model and hierarchical system for each CI sector was not possible without the participation of CI operators. The results of the flood risk network analysis were verified anecdotally by checking social media posts during that time. This verified the disruption of electricity and ICT supply in three specific locations and showed that disruption in the freshwater supply could not be shown in the results but was mentioned in social media posts. When deriving general statements from this study, it must be considered that this proof-of-concept is applied to a relatively small catchment area and that only fluvial flooding is considered. For more general discussions, it is recommended to consider other spatial extents and types of natural hazards.

The flood measure catalog can be divided into two types of measures. Firstly, flood risk-reducing measures that prevent harmful consequences, and secondly, resilience-enhancing measures that focus on capacity and adaptive capabilities. The presented case study showed that the recovery time can be included in a modeling approach and be quantified in the flood risk for population disruption time (cf. Equation (2)). Therefore, measures initially regarded as resilience-enhancing are included in the risk concept. Nevertheless, the modeling approach does not have the capability to incorporate all resilience-enhancing measures (cf. Table 2) that have been identified, which outlines the limitation of the presented method. More data-determining attributes such as recovery time or threshold values are needed and can help extend what is to be considered in a model-based flood risk management approach.

6. Conclusions

It is concluded that a flood measure catalog for critical infrastructures can be applied in network model-driven flood risk analysis.

A literature study and interviews with CI experts were conducted and assembled into a CI flood measure catalog. The catalog is structured for five CI sectors and offers a generalized category. This structure was further differentiated for each stage of the DRR cycle. Thus, the catalog can be used to further develop CI network case studies for the implementation stage by suggesting practical measures to the scientific community. At the same time, the catalog helps to verify the applicability of CI network analysis methods: the more measures that can be included, the more applicable an analysis method may be. However, a range of measures remains either unquantifiable or, at the very least, presents significant challenges in quantification, particularly concerning organizational measures

The measure catalog is used to extend a state-of-the-science flood risk analysis for CIN by considering potential flood measures, thus paving the way from flood risk analysis to flood risk management for CI. The presented case study of a small catchment in the west of Germany provides a proof-of-concept for the application of the measure catalog. The CIN Module from the ProMaIDes framework is used to combine the CI network modeling, hydrological probabilities, and spatial and quantitative hydraulic model results. It is shown that flood risk as a concept can be used to derive a solid metric to describe flood consequences in the CI domain including the consideration of probabilities. A network modeling approach was used to check the effectiveness of some CI measures, while at the same time, the limitations of the chosen network modeling method have been explored in the discussion. Effective measures could be checked, and a significant reduction in the affected population could be proven for the catchment area, and the overall resilience of the CI network could increase.

This method ultimately provides policymakers and stakeholders in the CI domain with a quantified, risk-based foundation for making informed decisions on sector-specific measures to enhance infrastructure resilience in each step of the DRR management cycle.

Author Contributions

R.S.: conceptualization, methodology visualization, writing—original draft; D.B.: writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Germany’s Federal Ministry of Education and Research within the framework of IKARIM and the PARADeS Project (Grant Number 13N15273).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to the associated security risk of assembled critical infrastructure datasets.

Acknowledgments

Map data copyrighted by OpenStreetMap contributors and available from www.openstreetmap.org (accessed on 6 January 2023). During the preparation of this study, the authors used GPT-3.5 from OpenAI and Paperpal to rephrase specific statements. After using these tools, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UNDRR. Addressing the Infrastructure Failure Data Gap: A Governance Challeng. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/addressing-infrastructure-failure-data-gap-governance-challenge (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- Rinaldi, S.; Peerenboom, J.; Kelly, T. Identifying, understanding, and analyzing critical infrastructure interdependencies. IEEE Control. Syst. 2001, 21, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, A. Critical infrastructure and flood resilience: Cascading effects beyond water. WIREs Water 2019, 6, e1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotten, R.; Bachmann, D. Integrating Critical Infrastructure Networks into Flood Risk Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klijn, F.; Kreibich, H.; de Moel, H.; Penning-Rowsell, E. Adaptive flood risk management planning based on a comprehensive flood risk conceptualisation. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Chang. 2015, 20, 845–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, R.; Thacker, S.; Hall, J.; Alderson, D.; Barr, S. Critical infrastructure impact assessment due to flood exposure. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2018, 11, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlhofer, E.; Koks, E.E.; Kropf, C.M.; Sansavini, G.; Bresch, D.N. A generalized natural hazard risk modelling framework for infrastructure failure cascades. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 234, 109194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Cha, E.J. Modeling the damage and recovery of interdependent civil infrastructure network using Dynamic Integrated Network model. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2018, 5, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, H.J.; De Bruijn, K.M.; Gersonius, B. Assessment of Critical Infrastructure Resilience to Flooding Using a Response Curve Approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotten, R.; Bachmann, D. Critical infrastructure network modelling for flood risk analyses: Approach and proof of concept in Accra, Ghana. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2023, 16, e12913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, D. Contribution to the Development of a Decision Support System for the Assessment and Planning of Flood Protection Measures (Beitrag zur Entwicklung eines Entscheidungsunterstützungssystems zur Bewertung und Planung von Hochwasserschutzmaßnahmen). Ph.D. Thesis, RWTH Aachen, Aachen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ani, U.D.; Watson, J.D.M.; Nurse, J.R.C.; Cook, A.; Maples, C. A review of critical infrastructure protection approaches: Improving security through responsiveness to the dynamic modelling landscape. In Proceedings of the Living Internet Things IoT 2019, London, UK, 1–2 May 2019; p. 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, V.; Long, S.; Shoberg, T.; Corns, S.; Carlo, H. Post-Disaster Supply Chain Interdependent Critical Infrastructure System Restoration: A Review of Data Necessary and Available for Modeling. Data Sci. J. 2016, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotten, R.; Mühlhofer, E.; Chatzistefanou, G.-A.; Bachmann, D.; Chen, A.S.; Koks, E.E. Data for critical infrastructure network modelling of natural hazard impacts: Needs and influence on model characteristics. Resilient Cities Struct. 2024, 3, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German Federal Office of Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance (BBK). Definition of CI Hazards—KRITIS-Gefahren , BBK. Available online: https://www.bbk.bund.de/DE/Themen/Kritische-Infrastrukturen/KRITIS-Gefahrenlagen/kritis-gefahrenlagen_node.html (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Petit, F.D.; Bassett, G.W.; Black, R.; Buehring, W.A.; Collins, M.J.; Dickinson, D.C.; Fisher, R.E.; Haffenden, R.A.; Huttenga, A.A.; Klett, M.S.; et al. Resilience Measurement Index: An Indicator of Critical Infrastructure Resilience; Argonne National Laboratory: Argonne, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- St-Laurent, G.P.; Oakes, L.E.; Cross, M.; Hagerman, S. R–R–T (resistance–resilience–transformation) typology reveals differential conservation approaches across ecosystems and time. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourbesville, P.; Batica, J. Flood Resilience Index—Methodology And Application. In International Conference on Hydroinformatics; CUNY Academic Works: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. 2015. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030 (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Attems, M.; Thaler, T.; Genovese, E.; Fuchs, S. Implementation of property-level flood risk adaptation (PLFRA) measures: Choices and decisions. WIREs Water 2020, 7, e1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H.; Hartmann, T. The FLOODLABEL as a social innovation in flood risk management to increase homeowners’ resilience. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2023, e12962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruijn, K.M.; Maran, C.; Zygnerski, M.; Jurado, J.; Burzel, A.; Jeuken, C.; Obeysekera, J. Flood Resilience of Critical Infrastructure: Approach and Method Applied to Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Water 2019, 11, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, B.A.; Mostafavi, A. Resilience of Infrastructure Systems to Sea-Level Rise in Coastal Areas: Impacts, Adaptation Measures, and Implementation Challenges. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamvakeridou-Lyroudia, L.; Chen, A.; Khoury, M.; Gibson, M.; Kostaridis, A.; Stewart, D.; Wood, M.; Djordjevic, S.; Savic, D. Assessing and visualising hazard impacts to enhance the resilience of Critical Infrastructures to urban flooding. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 707, 136078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lendering, K.; Jonkman, S.; Kok, M. Effectiveness of emergency measures for flood prevention. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2015, 9, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreibich, H.; Bubeck, P.; Van Vliet, M.; De Moel, H. A review of damage-reducing measures to manage fluvial flood risks in a changing climate. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Chang. 2015, 20, 967–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anakhov, P.; Zhebka, V.; Grynkevych, G.; Makarenko, A. Protection of telecommunication network from natural hazards of global warming. East. Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2020, 3, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröbel, J. Documentation of Typical Damages and Impairments Caused by Flood Events in Gas Supply, Derivation of Preventive and Acute Action Recommendations—Dokumentation von Typischen Schäden und Beeinträchtigungen durch Hochwasserereignisse in der Gasversorgung, Ableitung von vorbeugenden und akuten Handlugnsempfehlungen; DBI Gasund Umwelttechnik GmbH: Leipzig, Germany, 2003; Available online: https://www.dvgw.de/medien/dvgw/gas/sicherheit/hochwasser-dbi.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Wricke, B.; Tränckner, J.; Böhler, E. Documentation of Typical Damages and Impairments of Water Supply Due to Flood Events, Derivation of Action Recommendations; German Association for Gas and Water—DVGW: Dresden, Germany, 2003; Available online: https://www.dvgw.de/medien/dvgw/gas/sicherheit/hochwasser-tzw.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Kong, J.; Zhang, C.; Simonovic, S.P. Optimizing the resilience of interdependent infrastructures to regional natural hazards with combined improvement measures. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 210, 107538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühne, L.M. Catalog of Measures for the Protection of Critical Infrastructure in the Event of a Flood—Maßnahmenkatalog Für den Schutz kritischer Infrastrukturen im Hochwasserfall. BSc. Thesis, University of Applied Sciences Magdeburg-Stendal, Magdeburg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- German Federal Ministry of the Interior (BMI). Protection of Critical Infrastructures—Risk and Crisis Management—Guide for Companies and Authorities—Schutz Kritischer Infrastrukturen—Risiko—Und Krisenmanagement. In Leitfaden für Unternehmen und Behörden; Bundesministerium des Innern: Berlin, Germany, 2011; Available online: https://www.bbk.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Mediathek/Publikationen/KRITIS/bmi-schutz-kritis-risiko-und-krisenmanagement.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=9 (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- German Federal Office for Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance (BBK). Stromausfall—Grundlagen und Methoden zur Reduzierung des Ausfallrisikos der Stromversorgung. 2019. Available online: https://www.bbk.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Mediathek/Publikationen/WF/WF-12-stromausfall.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=6 (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- German Federal Ministry for Housing, Urban Development, and Building (BMWSB). Flood Protection Primer—Object Protection and Structural Precautions—Hochwasserschutzfibel—Objektschutz und bauliche Vorsorge. February 2022. Available online: https://www.fib-bund.de/Inhalt/Themen/Hochwasser/2022-02_Hochwasserschutzfibel_9.Auflage.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Gläser, J.; Laudel, G. Expert interviews and Qualitative Content Analysis—Experteninterviews und Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse; VS Verlag: Zurich, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Folkens, L.; Bachmann, D.; Schneider, P. Driving Forces and Socio-Economic Impacts of Low-Flow Events in Central Europe: A Literature Review Using DPSIR Criteria. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German Association for Water, Wastewater and Waste (DWA). Guideline DWA-M 103—Flood Protection for Sewage Systems—Merkblatt DWA-M 103—Hochwasserschutz für Abwasseranlagen. October 2013. Available online: https://shop.dwa.de/DWA-M-103-Hochwasserschutz-Abwasser-10-2013/M-103-PDF-13 (accessed on 21 February 2024).

- German Technical and Scientific Association for Gas and Water (DVGW). Technical Note—Guideline DVGW G 479 (M) Planning, Construction, and Operation of Gas Installations in Flood-Prone Areas—Technischer Hinweis—Merkblatt DVGW G 479 (M) Planung, Errichtung und Betrieb von Gasanlagen in Hochwassergefährdungsbereichen. February 2017. Available online: https://shop.wvgw.de/G-479-Merkblatt-02-2017/309853 (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Assmann, A.; Beck, R.; Buschlinger, M.; Dörr, A.; Fuchs, L.; Göppert, H.; Göttlicher, J.; van Riesenbeck, G.G.; Hille, H.; Illgen, M.; et al. Heavy Rainfall and Urban Flash Floods—Practical Guide for Flood Protection—Starkregen und urbane Sturzfluten—Praxisleitfaden zur Überflutungsvorsorge; DWA: Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Asaridis, P.; Molinari, D. A conceptual model for the estimation of flood damage to power grids. Adv. Geosci. 2023, 61, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruijn, K.; Hurk, B.V.D.; Slager, K.; Rongen, G.; Hegnauer, M.; Van Heeringen, K.J. Storylines of the impacts in the Netherlands of alternative realizations of the Western Europe July 2021 floods. J. Coast. Riverine Flood Risk 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenStreetMap Contributors. Planet Dump Retrieved from Planet OSM. 2017. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org/ (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Bachmann, D. ProMaIDes—Knowledge Base & User Documentation. Available online: https://promaides.myjetbrains.com/youtrack/articles/PMID-A-7/General (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Poirier, L.; Knox, P.; Murphy, E.; Provan, M. Flood Damage to Critical Infrastructure; National Research Council Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koks, E.E.; van Ginkel, K.C.H.; van Marle, M.J.E.; Lemnitzer, A. Brief communication: Critical infrastructure impacts of the 2021 mid-July western European flood event. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 22, 3831–3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meta—Data for Good. High Resolution Population Density Maps. Available online: https://dataforgood.facebook.com/dfg/docs/methodology-high-resolution-population-density-maps (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Facebook. Stolberg (Rhld.)—Our City, Our Home—Unsere Stadt, Unsere Heimat Facebook. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/659421950813305 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Sathurshan, M.; Saja, A.; Thamboo, J.; Haraguchi, M.; Navaratnam, S. Resilience of Critical Infrastructure Systems: A Systematic Literature Review of Measurement Frameworks. Infrastructures 2022, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, R. Chronicle detailing the progression of the floods of the Weißeritz and Elbe rivers in August 2002 within the territory of the state capital Dresden as observed by the municipal enterprise “Stadtentwässerung Dresden”—Chronik zum Verlauf des Hochwassers von Weißeritz und Elbe im August 2002 auf dem Territorium der Landeshauptstadt Dresden aus Sicht des Eigenbetriebes “Stadtentwässerung Dresden”. In State capital—Landeshauptstadt Dresden; Urban drainage—Stadtentwässerung Dresden: Dresden, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank and Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation. Financial Protection of Critical Infrastructure Services PreventionWeb. Washington, March 2021. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/publication/financial-protection-critical-infrastructure-services (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Calcutt, E.; Ranger, N. Five Reasons You Should Be Thinking About Compounding Risks Now. Financial Protection Forum. Available online: https://www.financialprotectionforum.org/blog/five-reasons-you-should-be-thinking-about-compounding-risks-now (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Emanuelsson, M.; McIntyre, N.; Hunt, C.; Mawle, R.; Kitson, J.; Voulvoulis, N. Flood risk assessment for infrastructure networks. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2014, 7, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).