Social Frailty Leads to the Development of Physical Frailty among Physically Non-Frail Adults: A Four-Year Follow-Up Longitudinal Cohort Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

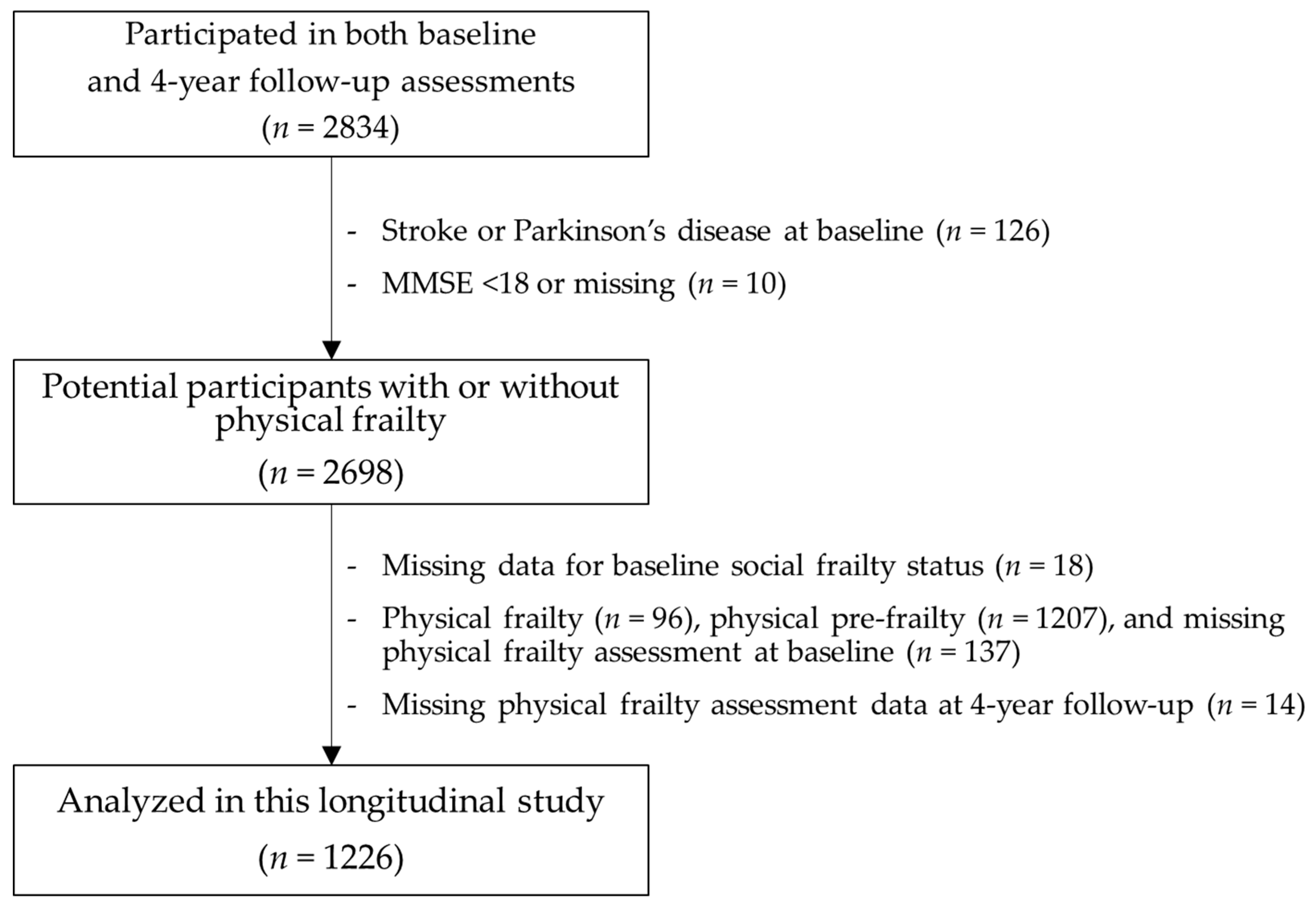

2.1. Participants

2.2. Physical Frailty

2.3. Social Frailty

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Subsection Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Associations between Social Frailty and the Development of Physical Frailty

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clegg, A.; Young, J.; Iliffe, S.; Rikkert, M.O.; Rockwood, K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013, 381, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tom, S.E.; Adachi, J.D.; Anderson, F.A., Jr.; Boonen, S.; Chapurlat, R.D.; Compston, J.E.; Cooper, C.; Gehlbach, S.H.; Greenspan, S.L.; Hooven, F.H.; et al. Frailty and fracture, disability, and falls: A multiple country study from the global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garre-Olmo, J.; Calvo-Perxas, L.; Lopez-Pousa, S.; de Gracia Blanco, M.; Vilalta-Franch, J. Prevalence of frailty phenotypes and risk of mortality in a community-dwelling elderly cohort. Age Ageing 2013, 42, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeiren, S.; Vella-Azzopardi, R.; Beckwee, D.; Habbig, A.K.; Scafoglieri, A.; Jansen, B.; Bautmans, I. Gerontopole Brussels Study Group. Frailty and the prediction of negative health outcomes: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 1163e1–1163e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockwood, K. What would make a definition of frailty successful? Age Ageing 2005, 34, 432–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobbens, R.J.; Luijkx, K.G.; Wijnen-Sponselee, M.T.; Schols, J.M. Toward a conceptual definition of frail community dwelling older people. Nurs. Outlook 2010, 58, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogan, D.B.; MacKnight, C.; Bergman, H. Steering Committee, Canadian Initiative on Frailty and Aging. Aging: Models, definitions, and criteria of frailty. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2003, 15 (Suppl. 3), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Levers, M.J.; Estabrooks, C.A.; Ross Kerr, J.C. Factors contributing to frailty: Literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 56, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, N.; Gao, Q.; Nyunt, M.S.Z.; Wee, S.L.; Ng, T.P. Social frailty and functional disability: Findings from the Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Studies. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 637e13–637e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makizako, H.; Shimada, H.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Lee, S.; Doi, T.; Nakakubo, S.; Hotta, R.; Suzuki, T. Social frailty in community-dwelling older adults as a risk factor for disability. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 1003.e7–1003.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew, M.K.; Mitnitski, A.B.; Rockwood, K. Social vulnerability, frailty and mortality in elderly people. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew, M.K. Frailty and social vulnerability. Interdiscip. Top. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2015, 41, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Shinkai, S.; Kumagai, S.; Amano, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Kim, H.; Suzuki, T.; Ishizaki, T.; Haga, H.; et al. Longitudinal changes in higher-level functional capacity of an older population living in a Japanese urban community. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2003, 36, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, J.S.; Oude Voshaar, R.C.; Zuidema, S.U.; Stolk, R.P.; Zuidersma, M.; Smidt, N. The relationship between social functioning and subjective memory complaints in older persons: A population-based longitudinal cohort study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 32, 1059–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchman, A.S.; Boyle, P.A.; Wilson, R.S.; Fleischman, D.A.; Leurgans, S.; Bennett, D.A. Association between late-life social activity and motor decline in older adults. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchman, A.S.; Boyle, P.A.; Wilson, R.S.; James, B.D.; Leurgans, S.E.; Arnold, S.E.; Bennett, D.A. Loneliness and the rate of motor decline in old age: The Rush Memory and Aging Project, a community-based cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2010, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zunzunegui, M.V.; Alvarado, B.E.; Del Ser, T.; Otero, A. Social networks, social integration, and social engagement determine cognitive decline in community-dwelling Spanish older adults. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2003, 58, S93–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaka, J.; Thompson, S.; Palacios, R. The relation of social isolation, loneliness, and social support to disease outcomes among the elderly. J. Aging Health 2006, 18, 359–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsutsumimoto, K.; Doi, T.; Makizako, H.; Hotta, R.; Nakakubo, S.; Makino, K.; Suzuki, T.; Shimada, H. Association of social frailty with both cognitive and physical deficits among older people. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, H.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Lee, S.; Doi, T.; Makizako, H.; Lee, S.; Harada, K.; Hotta, R.; Bae, S.; Nakakubo, S.; et al. Driving continuity in cognitively impaired older drivers. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2016, 16, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, H.; Makizako, H.; Lee, S.; Doi, T.; Lee, S.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Harada, K.; Hotta, R.; Bae, S.; Nakakubo, S.; et al. Impact of Cognitive Frailty on Daily Activities in Older Persons. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2016, 20, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, H.; Makizako, H.; Doi, T.; Yoshida, D.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Anan, Y.; Uemura, K.; Ito, T.; Lee, S.; Park, H.; et al. Combined prevalence of frailty and mild cognitive impairment in a population of elderly Japanese people. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.K.; Liu, L.K.; Woo, J.; Assantachai, P.; Auyeung, T.W.; Bahyah, K.S.; Chou, M.Y.; Chen, L.Y.; Hsu, P.S.; Krairit, O.; et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: Consensus report of the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014, 15, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukutomi, E.; Okumiya, K.; Wada, T.; Sakamoto, R.; Ishimoto, Y.; Kimura, Y.; Chen, W.L.; Imai, H.; Kasahara, Y.; Fujisawa, M.; et al. Relationships between each category of 25-item frailty risk assessment (Kihon Checklist) and newly certified older adults under Long-Term Care Insurance: A 24-month follow-up study in a rural community in Japan. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2015, 15, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, H.; Makizako, H.; Doi, T.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Suzuki, T. Incidence of disability in frail older persons with or without slow walking speed. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 690–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makizako, H.; Shimada, H.; Doi, T.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.C.; Harada, K.; Hotta, R.; Nakakubo, S.; Bae, S.; et al. Age-dependent changes in physical performance and body composition in community-dwelling Japanese older adults. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2017, 8, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobbens, R.J.; van Assen, M.A.; Luijkx, K.G.; Wijnen-Sponselee, M.T.; Schols, J.M. Determinants of frailty. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2010, 11, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunt, S.; Steverink, N.; Andrew, M.K.; Schans, C.P.V.; Hobbelen, H. Cross-cultural adaptation of the social vulnerability index for use in the Dutch context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, I.A.; Hubbard, R.E.; Andrew, M.K.; Llewellyn, D.J.; Melzer, D.; Rockwood, K. Neighborhood deprivation, individual socioeconomic status, and frailty in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2009, 57, 1776–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado, B.E.; Zunzunegui, M.V.; Beland, F.; Bamvita, J.M. Life course social and health conditions linked to frailty in Latin American older men and women. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2008, 63, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makizako, H.; Shimada, H.; Doi, T.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Suzuki, T. Impact of physical frailty on disability in community-dwelling older adults: A prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, C.L.; Sniehotta, F.F.; Vadiveloo, T.; Argo, I.S.; Donnan, P.T.; McMurdo, M.E.T.; Witham, M.D. Factors associated with change in objectively measured physical activity in older people—Data from the physical activity cohort Scotland study. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, Y.; Park, N.S.; Dominguez, D.D.; Molinari, V. Social engagement in older residents of assisted living facilities. Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Holle, V.; Van Cauwenberg, J.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Deforche, B.; Van de Weghe, N.; Van Dyck, D. Interactions between neighborhood social environment and walkability to explain Belgian older adults’ physical activity and sedentary time. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, E569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McAuley, E.; Blissmer, B.; Marquez, D.X.; Jerome, G.J.; Kramer, A.F.; Katula, J. Social relations, physical activity, and well-being in older adults. Prev. Med. 2000, 31, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.L.; Robitaille, A.; Zelinski, E.M.; Dixon, R.A.; Hofer, S.M.; Piccinin, A.M. Cognitive activity mediates the association between social activity and cognitive performance: A longitudinal study. Psychol. Aging 2016, 31, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Kwon, E.; Lee, H. Life course trajectories of later-life cognitive functions: Does social engagement in old age matter? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuiper, J.S.; Zuidersma, M.; Oude Voshaar, R.C.; Zuidema, S.U.; van den Heuvel, E.R.; Stolk, R.P.; Smidt, N. Social relationships and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 22, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saczynski, J.S.; Pfeifer, L.A.; Masaki, K.; Korf, E.S.; Laurin, D.; White, L.; Launer, L.J. The effect of social engagement on incident dementia: The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 163, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marioni, R.E.; Proust-Lima, C.; Amieva, H.; Brayne, C.; Matthews, F.E.; Dartigues, J.F.; Jacqmin-Gadda, H. Social activity, cognitive decline and dementia risk: A 20-year prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Mao, G.; Leng, S.X. Frailty syndrome: An overview. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Makizako, H.; Doi, T.; Shimada, H.; Park, H.; Uemura, K.; Yoshida, D.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Anan, Y.; Suzuki, T. Relationship between going outdoors daily and activation of the prefrontal cortex during verbal fluency tasks (VFTs) among older adults: A near-infrared spectroscopy study. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 56, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suda, M.; Takei, Y.; Aoyama, Y.; Narita, K.; Sato, T.; Fukuda, M.; Mikuni, M. Frontopolar activation during face-to-face conversation: An in situ study using near-infrared spectroscopy. Neuropsychologia 2010, 48, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hikichi, H.; Kondo, N.; Kondo, K.; Aida, J.; Takeda, T.; Kawachi, I. Effect of a community intervention programme promoting social interactions on functional disability prevention for older adults: Propensity score matching and instrumental variable analyses, JAGES Taketoyo study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2015, 69, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Social Non-Frailty (n = 932) | Social Pre-Frailty (n = 250) | Social Frailty (n = 44) | p a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD (years) | 70.4 ± 4.1 | 70.4 ± 4.0 | 71.3 ± 5.8 | 0.340 |

| Women, n (%) | 482 (51.7%) | 126 (50.4%) | 25 (56.8%) | 0.871 |

| Medical history, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 353 (37.9%) | 99 (39.6%) | 18 (40.9%) | 0.541 |

| Heart disease | 138 (14.8%) | 39 (15.6%) | 4 (9.1%) | 0.654 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 86 (9.2%) | 24 (9.6%) | 4 (9.1%) | 0.914 |

| Osteoporosis b | 91 (9.8%) | 32 (12.8%) | 2 (4.5%) | 0.785 |

| Prescribed medications, mean ± SD (number) | 1.5 ± 1.7 | 1.7 ± 2.0 | 1.8 ± 1.5 | 0.191 |

| BMI, mean ± SD (kg/m2) | 23.3 ± 3.0 | 23.3 ± 3.1 | 23.3 ± 3.0 | 0.959 |

| Physical performance | ||||

| Grip strength, mean ± SD (kg) | 29.0 ± 7.4 | 28.5 ± 7.5 | 28.1 ± 7.4 | 0.567 |

| Walking speed, mean ± SD (m/s) | 1.32 ± 0.17 | 1.30 ± 0.17 | 1.25 ± 0.16 | 0.009 |

| Baseline Status of Social Frailty | Dependent Value: Incidence of Physical Frailty | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Not socially frail | 1 | [Reference] | 1 | [Reference] | 1 | [Reference] |

| Socially pre-frail | 1.50 | 0.58–3.92 | 1.49 | 0.57–3.90 | 1.22 | 0.45–3.25 |

| Socially frail | 4.47 * | 1.25–16.06 | 3.98 * | 1.09–14.59 | 3.93 * | 1.02–15.15 |

| Baseline Status of Social Frailty | Dependent Value: Incidents Related to Physical Frailty or Pre-Frailty | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Not socially frail | 1 | [Reference] | 1 | [Reference] | 1 | [Reference] |

| Socially pre-frail | 1.26 | 0.94–1.67 | 1.27 | 0.95–1.69 | 1.17 | 0.87–1.58 |

| Socially frail | 2.84 ** | 1.53–5.29 | 2.75 ** | 1.46–5.19 | 2.50 ** | 1.30–4.80 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makizako, H.; Shimada, H.; Doi, T.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Hotta, R.; Nakakubo, S.; Makino, K.; Lee, S. Social Frailty Leads to the Development of Physical Frailty among Physically Non-Frail Adults: A Four-Year Follow-Up Longitudinal Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030490

Makizako H, Shimada H, Doi T, Tsutsumimoto K, Hotta R, Nakakubo S, Makino K, Lee S. Social Frailty Leads to the Development of Physical Frailty among Physically Non-Frail Adults: A Four-Year Follow-Up Longitudinal Cohort Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(3):490. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030490

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakizako, Hyuma, Hiroyuki Shimada, Takehiko Doi, Kota Tsutsumimoto, Ryo Hotta, Sho Nakakubo, Keitaro Makino, and Sangyoon Lee. 2018. "Social Frailty Leads to the Development of Physical Frailty among Physically Non-Frail Adults: A Four-Year Follow-Up Longitudinal Cohort Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 3: 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030490