A Study on the Applicability of Kinetic Models for Shenfu Coal Char Gasification with CO2 at Elevated Temperatures

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Models

| Models | Integral expression | Differential expression | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUCM | k is the average reaction rate constant. | ||

| RPM | τ, A0 and ψ are respectively the dimensionless time, the initial reaction rate and the pore structural parameter. | ||

| MVM | A and B are two constants and determined from the conversion versus time data by the least-squares method. |

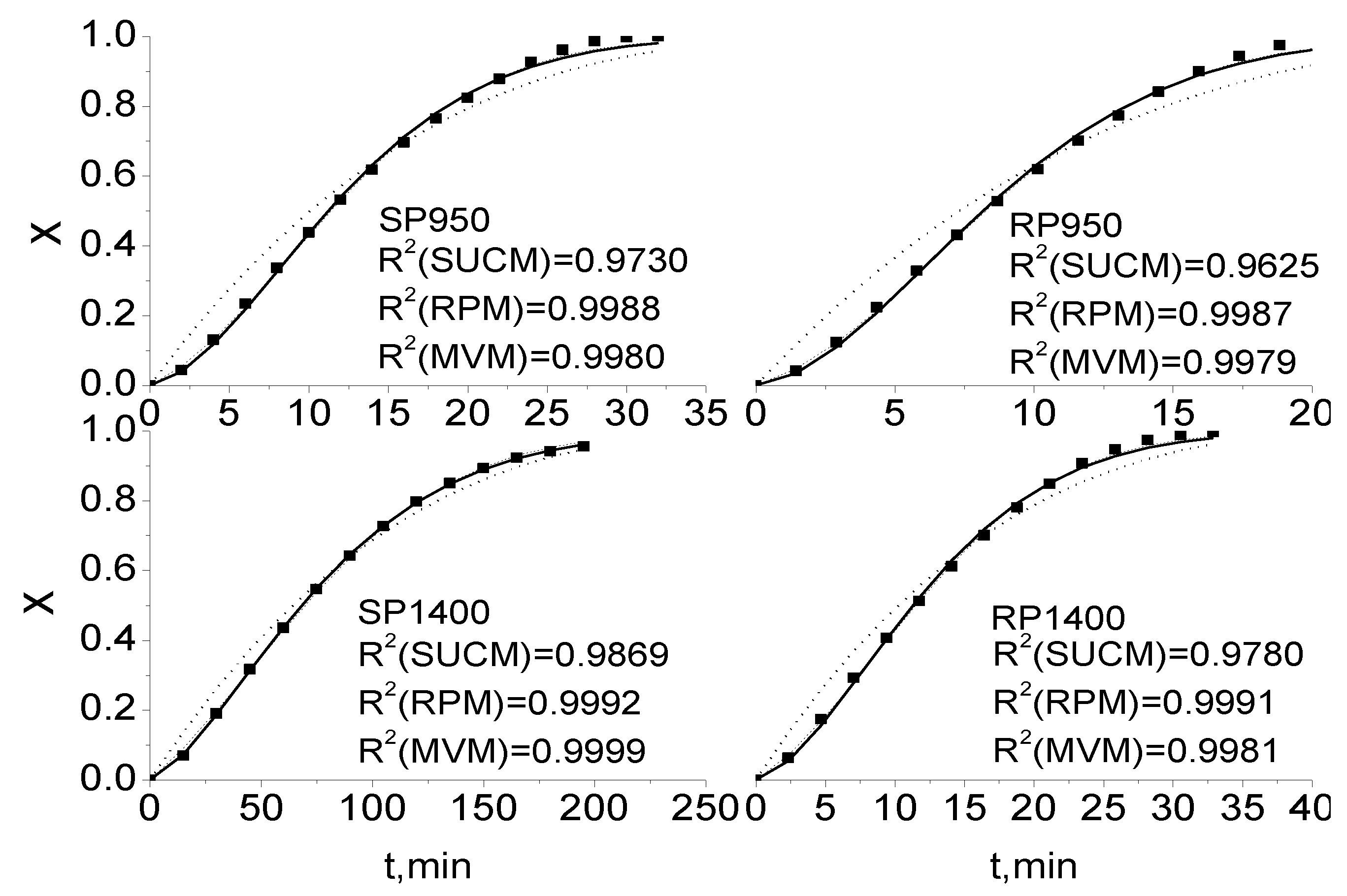

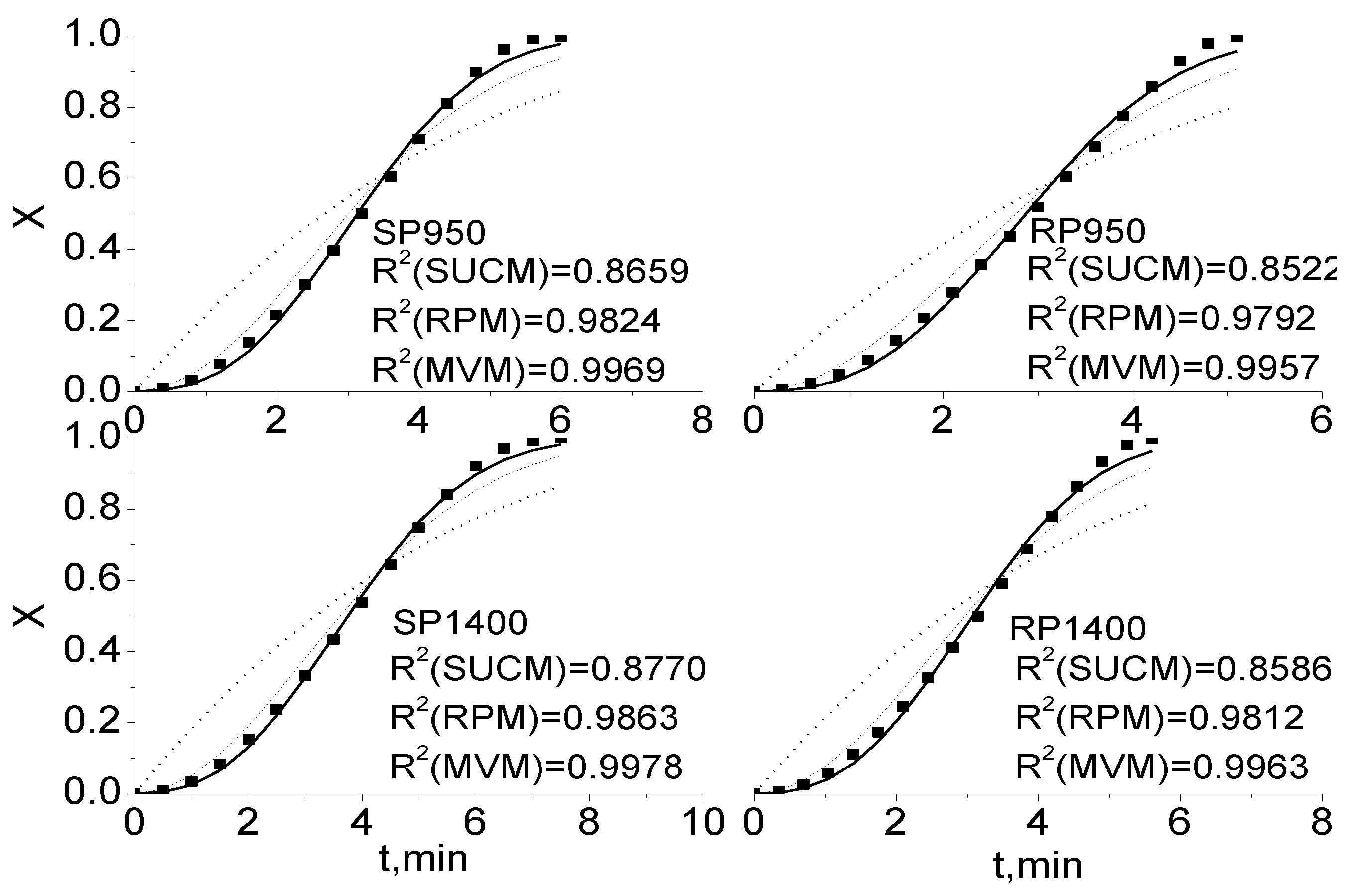

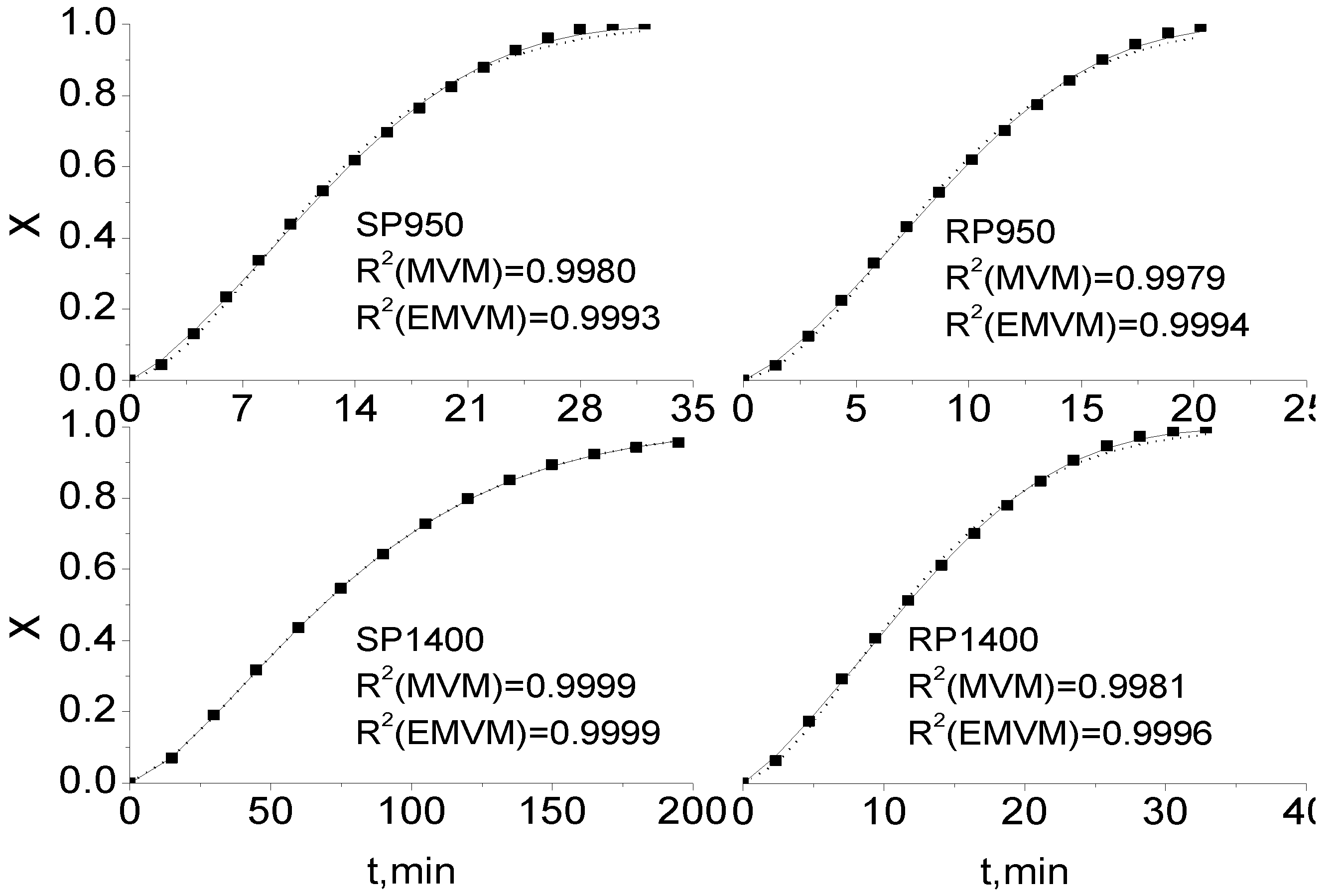

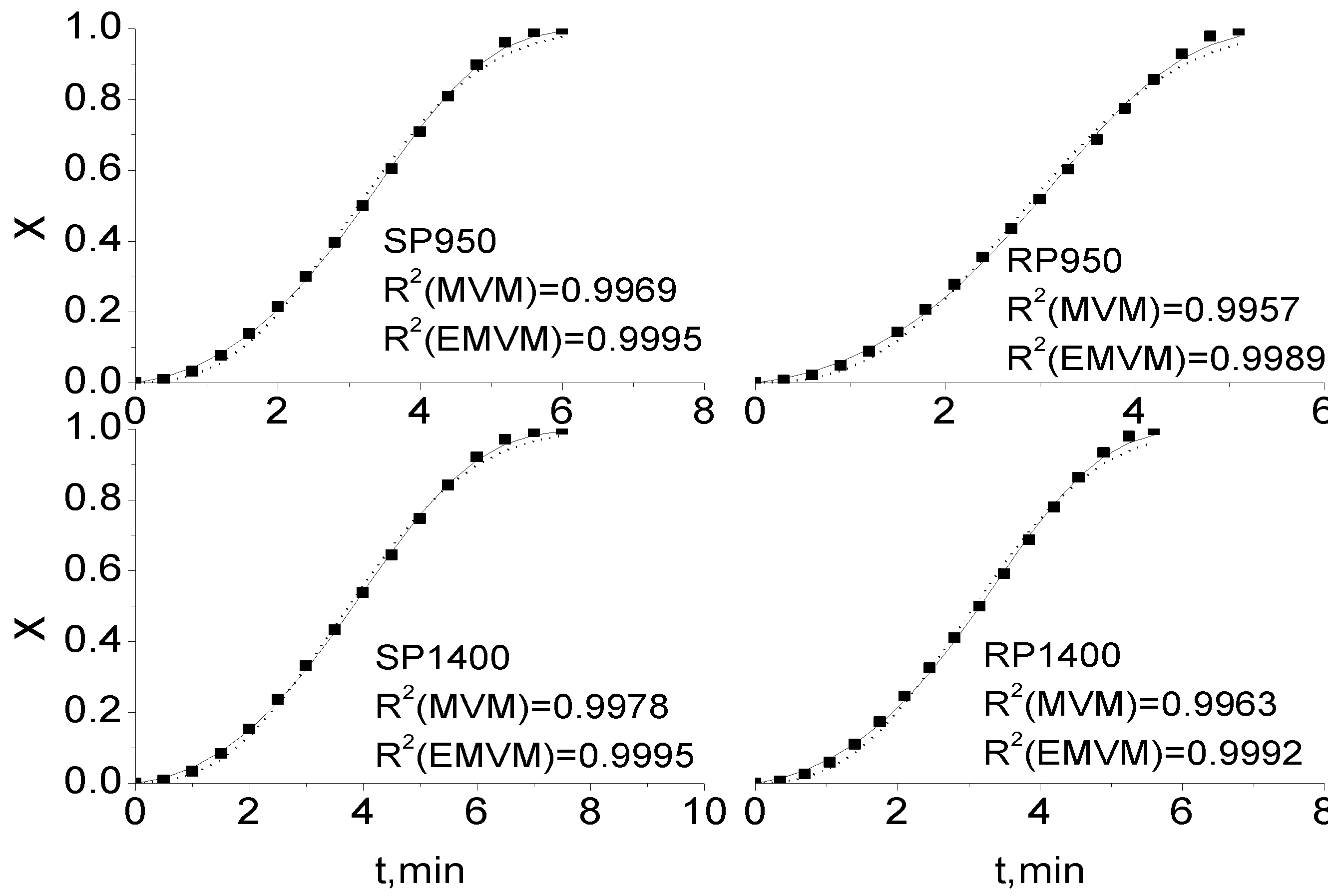

2.2. Comparisons of SUCM, RPM and MVM for Coal Char Gasification

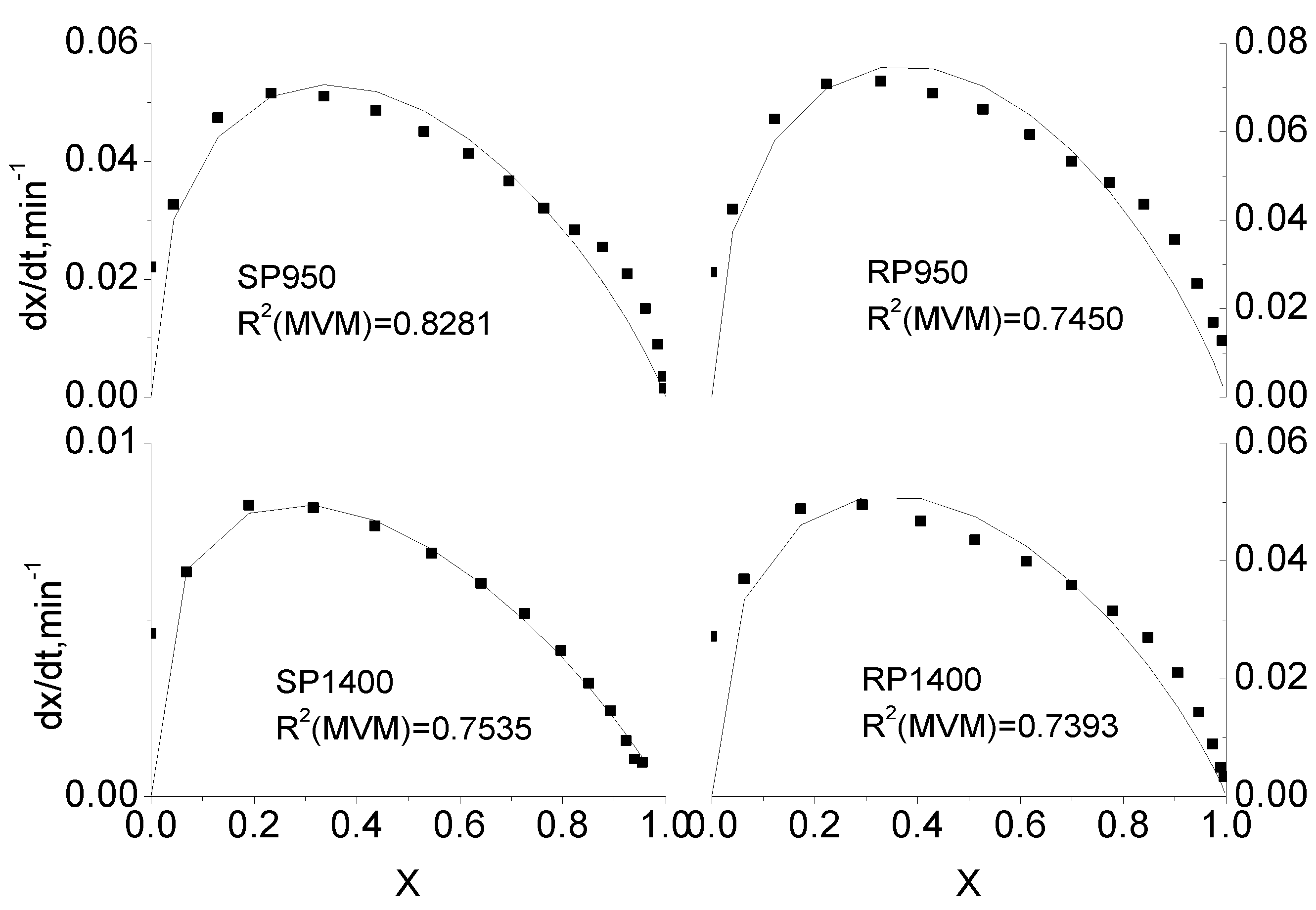

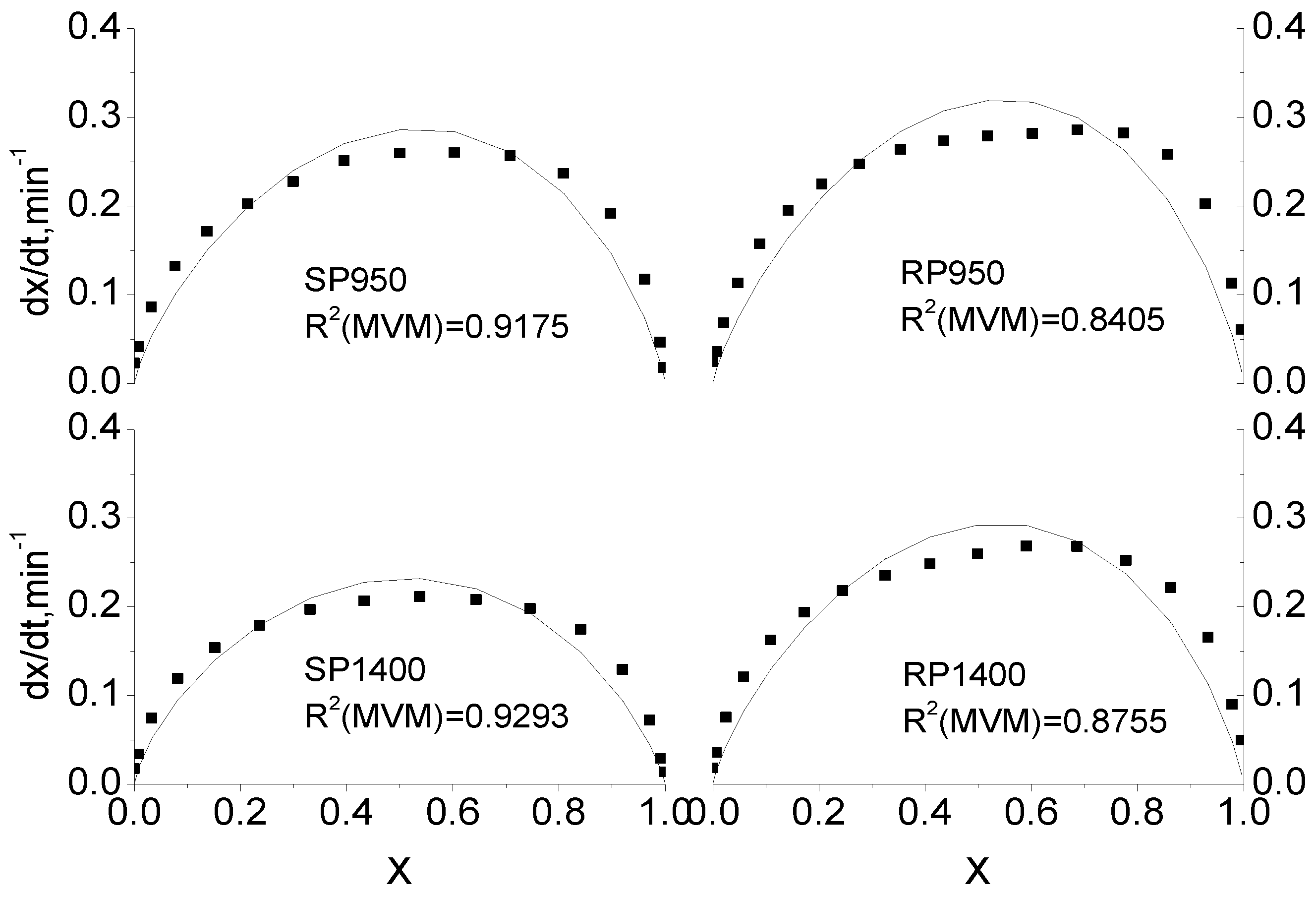

2.3. Comparison of Integral and Differential Expressions of the MVM for Coal Char Gasification

2.4. Extension of Modified Volumetric Model for Coal Char Gasification

| SP950 | RP950 | SP1400 | RP1400 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gasification temperature (°C) | MVM | EMVM | MVM | EMVM | MVM | EMVM | MVM | EMVM |

| 950 | 0.99799 | 0.99932 | 0.99787 | 0.99940 | 0.99991 | 0.99991 | 0.99805 | 0.99963 |

| 1,000 | 0.99783 | 0.99949 | 0.99815 | 0.99975 | 0.99994 | 0.99996 | 0.99922 | 0.99986 |

| 1,100 | 0.99742 | 0.99968 | 0.99754 | 0.99964 | 0.99989 | 0.99990 | 0.99897 | 0.99991 |

| 1,200 | 0.99730 | 0.99976 | 0.99769 | 0.99964 | 0.99953 | 0.99986 | 0.99854 | 0.99980 |

| 1,300 | 0.99734 | 0.99961 | 0.99702 | 0.99931 | 0.99841 | 0.99981 | 0.99725 | 0.99940 |

| 1,400 | 0.99690 | 0.99948 | 0.99574 | 0.99890 | 0.99775 | 0.99954 | 0.99627 | 0.99922 |

| Gasification temperature (°C) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 950 | 1000 | 1100 | 1200 | 1300 | 1400 | |

| Constant A | ||||||

| SP950 | 0.01261 | 0.02110 | 0.02817 | 0.03290 | 0.02956 | 0.03501 |

| RP950 | 0.01839 | 0.0302 | 0.03446 | 0.03055 | 0.03879 | 0.04363 |

| SP1400 | 0.00141 | 0.00501 | 0.02272 | 0.02335 | 0.02191 | 0.02428 |

| RP1400 | 0.01404 | 0.02464 | 0.03434 | 0.03362 | 0.03751 | 0.03725 |

| Constant A★ | ||||||

| SP950 | 0.02413 | 0.03656 | 0.04266 | 0.04426 | 0.03966 | 0.04217 |

| RP950 | 0.03230 | 0.04786 | 0.04690 | 0.03994 | 0.04408 | 0.04564 |

| SP1400 | 0.00146 | 0.00544 | 0.02183 | 0.03031 | 0.03289 | 0.03475 |

| RP1400 | 0.02772 | 0.03549 | 0.04457 | 0.04354 | 0.04483 | 0.04319 |

3. Preparation of Chars and Gasification Experiments

| Samples | Proximate analysis (wt%, d) | Ultimate analysis (wt%, d) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | V | FC | C | H | St | N | |

| SP950 | 10.30 | 3.22 | 86.48 | 87.00 | 0.64 | 0.38 | 0.30 |

| SP1400 | 10.56 | 1.07 | 88.44 | 89.53 | 0.11 | 0.38 | 0.02 |

| RP950 | 10.41 | 6.14 | 83.45 | 83.68 | 1.73 | 0.33 | 1.04 |

| RP1400 | 11.32 | 3.07 | 85.61 | 87.05 | 0.51 | 0.38 | 0.08 |

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References and Notes

- Liu, G.; Tate, A.G.; Bryant, G.W.; Wall, T.F. Mathematical modeling of coal char reactivity with CO2 at high pressures and temperatures. Fuel 2000, 79, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Watanabe, T.; Nakamura, M.; Uemiya, S.; Kojima, T. Gasification kinetics of coal chars carbonized under rapid and slow heating conditions at elevated temperatures. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2001, 123, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowok, J.W; Hurley, J.P.; Bensen, S.A. The role of physical factors in mass transport during sintering of coal ashes and deposit deformation near the temperature of glass transformation. Fuel Process. Technol. 1998, 56, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhou, Z.J.; Gong, X.; Yu, Z.H. Study of char-CO2 gasification (I) by isothermal thermogravimetry. Coal Conversion 2002, 25, 66–69. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Kaneko, M.; Luo, C.; Kato, S.; Kojima, T. Effect of pyrolysis time on the gasification reactivity of char with CO2 at elevated temperatures. Fuel 2004, 83, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajitani, S.; Hara, S.; Matsuda, H. Gasification rate analysis of coal char with a pressurized drop tube furnace. Fuel 2002, 81, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.P.; Agnew, J.B.; Zhang, D.K. Gasification of an Austrailian low-rank coal with carbon dioxide and steam: kinetics and reactivity studies. Fuel 1998, 77, 1209–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Watkinson, A.P. Gasification reactivity of some Western Canadian coals. Fuel 1994, 73, 1786–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.F.; Sun, R.Z. Kinetic studies of a lignite char pressurized gasification with CO2, H2 and steam. Fuel 1994, 73, 413–416. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.F.; Liu, H.B. The application of unreacted-core shrinking model to coal chars with CO2 pressurized gasification reaction. Gas & Heat 1993, 13, 3–9. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wen, C.Y. Noncatalytic heterogeneous solid fluid reaction models. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1968, 60, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, W.; Perlmutter, D.D. The effect of pore structure on char-steam reaction. AIChE J. 1989, 35, 1791–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavalas, G.R. A random capillary model with application to char gasification at chemically controlled rates. AIChE J. 1980, 26, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Luo, C.H.; Kaneko, M.; Kato, S.; Kojima, T. Unification of gasification kinetics of char in CO2 at elevated temperatures with a modified random pore model. Energy Fuels 2003, 17, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, J.; Cassanello, M.C.; Bonelli, P.R.; Cukierman, A.L. CO2 gasification of Argentinean coal chars: a kinetic characterization. Fuel Process. Technol. 2001, 74, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasaoka, S.; Sakata, Y.; Tong, C. Kinetic evaluation of the reactivity of various coal chars for gasification with carbon dioxide in comparison with steam. Int. Chem. Eng. 1985, 25, 160–175. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.J.; Kim, S.D. Catalytic activity of alkali and transition metal salt mixtures for steam-char gasification. Fuel 1995, 74, 1387–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.H.; Sang, D. Catalytic activity of alkali and iron salt mixtures for steam-char gasification. Fuel 1993, 72, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.K.; Perlmutter, D.D. A random pore model for fluid-solid reactions: I isothermal, kinetic control. AIChE J. 1980, 26, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.Y.; Gu, J.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.Q.; Gao, J.S. Variation of the crystalline structure and CO2 gasification reactivity of Shenfu coal chars at elevated temperatures. Energy Fuels 2008, 22, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2009 by the authors. Licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.; Wu, S.; Gao, J. A Study on the Applicability of Kinetic Models for Shenfu Coal Char Gasification with CO2 at Elevated Temperatures. Energies 2009, 2, 545-555. https://doi.org/10.3390/en20300545

Wu Y, Wu S, Gao J. A Study on the Applicability of Kinetic Models for Shenfu Coal Char Gasification with CO2 at Elevated Temperatures. Energies. 2009; 2(3):545-555. https://doi.org/10.3390/en20300545

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Youqing, Shiyong Wu, and Jinsheng Gao. 2009. "A Study on the Applicability of Kinetic Models for Shenfu Coal Char Gasification with CO2 at Elevated Temperatures" Energies 2, no. 3: 545-555. https://doi.org/10.3390/en20300545