Being-in-the-Chemotherapy-Suite versus Being-in-the-Oncology-Ward: An Analytical View of Two Hospital Sites Occupied by People Experiencing Cancer †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Palliative care is the total care of people who are dying from active, progressive diseases or other conditions when curative or disease-modifying treatment has come to an end. Palliative care services are generally provided by a multidisciplinary team that works with the person who is dying and their family/whanau(2001, p. 2).

Hospital technology and institutional settings embody the ideologies of modern medicine in which the promise of cure is premised on the requirement of cooperation. To engage that ideology in hospital is not just to sign up to a set of beliefs but, in one’s own turn, to embody them in acts of acquiescence and resistance at a corporeal level. This bodily endorsement of the object’s constraint or intrusion is the anticipation of its purpose. Taken as a totalizing exercise, this is the act of becoming and remaining a hospital patient([16], pp. 93–94).

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Participants

2.3. Location

2.4. Ethnographic Data Collection

In actuality, from a purely ethnological, neutral-observer point of view, the behaviour occurring in the settings varies over a wide range and the recording of that variation… is extremely difficult. A portion of what people do and say may not be critical to either incorporating or challenging the emerging definition(p. 426).

3. Findings and Theoretical Framework

3.1. Transition and Rite of Passage—Van Gennep’s Theory

Helen’s statement shows how separation from familiar settings affected the participants, insofar as she perceived this separation as detrimental. Numerous other examples provide a sense of isolation and marginalisation felt by the participants. The following examples are also drawn from the researcher’s notes on Helen:“It was the bone cancer that threw me because it meant a whole change of lifestyle. We used to go away skiing all the time and I knew that I wouldn’t be able to do that anymore. I also used to work in the garden a lot and used to be able to haul huge wheelbarrows of mulch and stuff. Now suddenly I couldn’t do any of those things. I had to change my life”.[33]

Helen explained that she had been living with cancer for almost three years and mentioned that she no longer attended the cancer support group that she used to go to regularly. She said that she just kept in touch by phone with a few of the women who were still alive. When asked by the researcher why she had stopped going to the group, she explained that as time passed she went to the group less and less as it became an emotional struggle for her to hold onto hope that she might live, when so many of the women in the group died of their disease[33].

Helen also talks about a cross-stitch group she belonged to. They have lunch, a natter, and then sew from 12.30 to 3 p.m. Helen used to go there during chemo and they all knew she had cancer but no one ever asked her about it. ‘They didn’t even ask about the tumour in my head.’ Helen stopped going every week and attended fortnightly instead. Then she went less and less, as she couldn’t stand their lack of acknowledgement of her illness[33].

We walked into the dining room and took our usual seats at the table. As Jack sat down, he said, “my memory is getting so bad, I have an appointment at work at 1pm and I need to hang the washing out first”… I (researcher) asked him what the work appointment was about, was it a farewell, and he said, “You might be right. They have been holding my job open for me, but I don’t think they can do it anymore. I could never go back now, anyway”[33].

After a while, a nurse came in and got a box of gowns out, and then another nurse came in and got some chairs. Jack didn’t mind, though, because the room was familiar to him. He said, “this used to be my chemotherapy room”. He sounded a bit wistful, as chemotherapy is now a thing of the past for him. You could almost hear the lost hope in his voice[33].

“It’s strange, but I like coming here and I don’t find it morbid, because all the nurses are so nice and the people here are all going through the same thing as me. I will really miss this place and seeing the other patients”.

The nurse had come over to speak to Daniel while I was out getting him a cup of tea. When I came back and sat down he said, “The nurse said that’s it. No more work for Daniel. She said you’re on your way out. She said your days are over”. Daniel added, “I’m still going to keep pushing, don’t you worry. I don’t want to go yet”. I asked Daniel how he felt about her saying that. Daniel said he needed to know. He said he will slow down and still keep pushing for that goal[33].

Alice has made the decision to stop treatment because the side effects are making her so ill. She said that she didn’t think that she realized before that she was actually going to die because she was so used to being sick, so used to having cancer, and even though she knew she would never survive the cancer, she never really accepted the fact that she was going to die from it. She feels now that there is no future. That there is no hope. She thinks it will be fairly soon[33].

Alice said that Dennis’s friends think that she is insecure and neurotic but they don’t understand that if Dennis leaves in the morning and things are not okay, that could be the last time they see each other and it would be horrible if she died on the day they had had an argument[33].

She said that she has tried to encourage Chris [her husband] to take up golf and play more often. She said: “he needs to get into the habit of doing things on his own because I’m not going to be around for much longer”. She said that although she sees friends on her own, Chris doesn’t really, and she worries about how he will get on when she is gone. She said that she knew he would be very lonely. She also said that he would meet someone else one day. I asked her how she felt about that. She said that he was young enough and she hoped that he would find someone else to be happy with. She said that she hoped he would wait at least a year, though[33].

Jenni (Tom’s, sister) says that they have all been hanging out with each other since Tom died and it has been really nice. I asked her if they took him home and she said that they had taken him back to his place and he was in a room just off the lounge. She said it was a really nice feeling to have him there. I asked her how her sister Sara coped with it because she had made the comment at the hospice that she wouldn’t be going near him when he was dead. Jennie said that Sara had been great too and asked me if I knew that Sara had been there when he died, and I said no. She said, yeah Sara said that he just took one final breath and sighed and then he was gone. She said it was really nice and peaceful[30].

3.2. Material Culture—Introducing Richardson’s Theoretical Framework

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of the Two Primary Sites

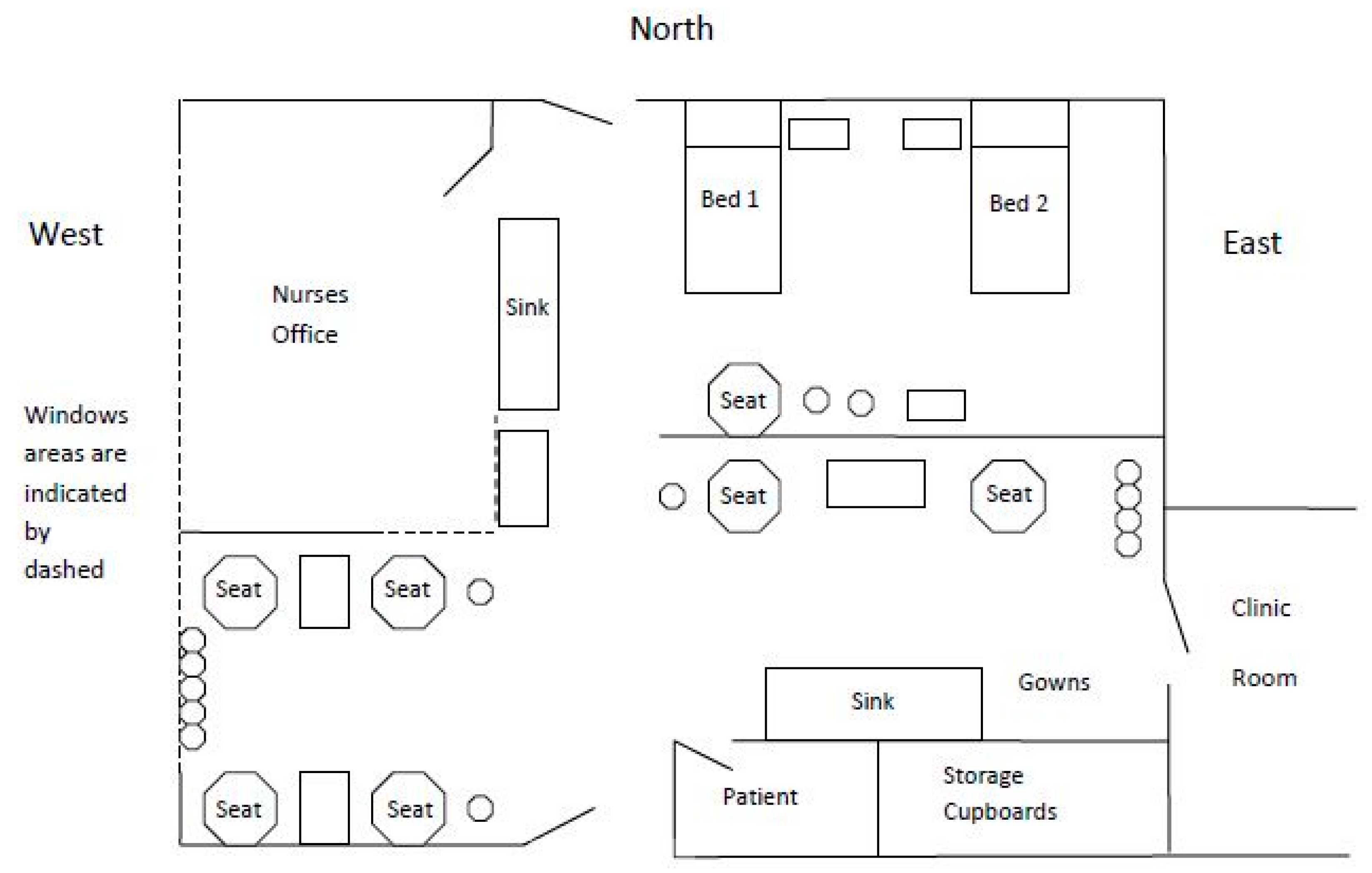

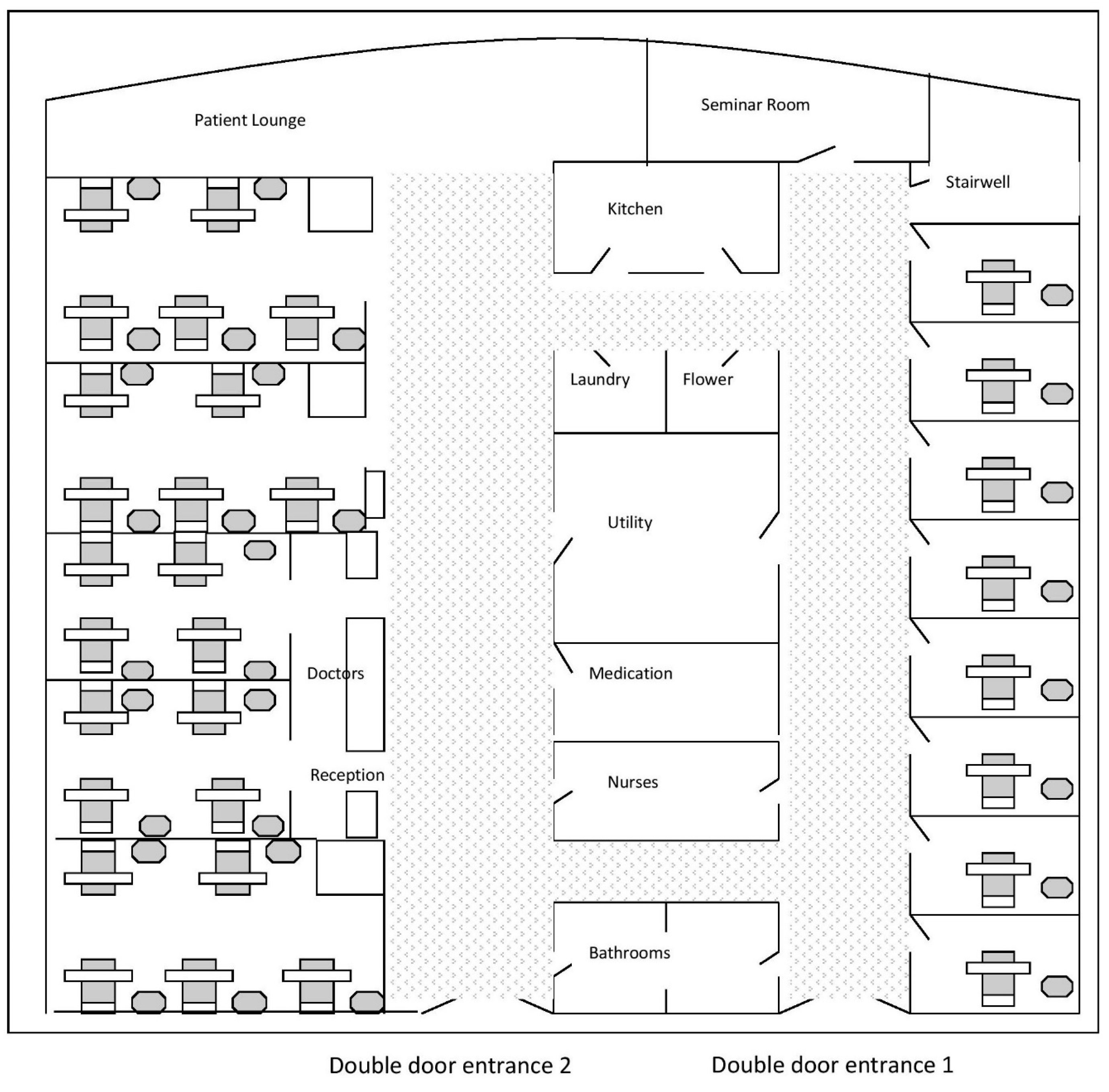

4.1.1. The Chemotherapy Suite

4.1.2. The Oncology Ward

4.1.3. Critical Contrast of the Two Material Settings

Since the ethnographer obviously wants to avoid the imposition of categories that do violence to the process he is trying to understand, the best way to handle both the “in” and “of” problem and the in-place and out-of-place distinction is to contrast a broad sample of market behaviour with that of the plaza and extract from that contrast critical interactions that illustrate the incorporation of the material setting into the emerging situations. This is attempted by making a more systematic comparison to underscore the contrast between market and plaza behaviour([31], p. 427).

4.1.4. Comparison of Interaction in the Two Settings

Alice has been admitted to the Oncology Ward. When I visit, she explains that she is writing a letter to the hospital board about the colour of the room and how she calls it the death ward. I said to her, well if you have to be admitted again, I will do what I can to brighten up the room.[33]

4.1.5. Theoretical Considerations of Interactions

The final step in the process of incorporating the setting into the ongoing situation is the objectification of the sense of the situation upon the setting so that the setting becomes a material image of the emerging situation([31], p. 85).

Alice says, I know she wasn’t good but I was just talking to her 5 min before she fell. I know people die in hospitals, but you just don’t expect to see it. I didn’t know she had died but the nurse told me when I asked where she had gone. After she fell, her family all arrived and were here for four hours. They had moved her to the side rooms, so I should have known.[33]

4.1.6. Contrast of the Two Images

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Health (MOH). The New Zealand Palliative Care Strategy; Ministry of Health: Wellington, New Zealand, 2001.

- Small, N. Social work and palliative care. Br. J. Soc. Work 2001, 31, 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, C.; Swami, N.; Krzyzanowska, M.; Leighl, N.; Rydall, A.; Rodin, G.; Tannock, I.; Hannon, B. Perceptions of palliative care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2016, 188, E217–E227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellershaw, J.; Ward, C. Care of the dying patient: The last hours or days of life. Br. Med. J. 2003, 326, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, M.; Rollison, B. A comparison of patients dying at home and patients dying at a hospice: Sociodemographic factors and caregivers’ experiences. Palliat. Support. Care 2003, 1, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, B.; Higginson, I. Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: Systematic review. Br. Med. J. 2006, 332, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, D. Between hope and acceptance: The medicalisation of dying. Br. Med. J. 2002, 324, 905–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSpelder, L.; Strickland, A. The Last Dance: Encountering Death and Dying; Palo Alto: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Fordham, S.; Dowrick, C. Is care of the dying improving? The contribution of specialist and non-specialist to palliative care. Fam. Pract. 1999, 16, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, A.; Zhang, B.; Keating, N.; Weeks, J.; Prigerson, H. Associations between palliative chemotherapy and adult cancer patients’ end of life care and place of death: Prospective cohort study. Br. Med. J. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broad, J.B.; Gott, M.; Kim, H.; Boyd, M.; Chen, H.; Connolly, M.J. Where do people die? An international comparison of the percentage of deaths occurring in hospital and residential aged care settings in 45 populations, using published and available statistics. Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copp, G. A review of current theories of death and dying. J. Adv. Nurs. 1998, 28, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, P.; Williams, H.; Maharaj, I. Patterns of end-of-life care. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2015, 17, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysaght, S.; Ersek, M. Settings of care within hospice. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2013, 15, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radley, A.; Taylor, D. Images of recovery: A photo-elicitation study on the hospital ward. Qual. Health Res. 2003, 13, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, P. Making sense: Embodiment and the sensibilities of the everyday. Environ. Plan. D 2000, 18, 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.R. Palliative Care in Context: An Ethnographic Account of the Journey from Diagnosis to the End of Life. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maso, I. Phenomenology and ethnography. In Handbook of Ethnography; Atkinson, A.C.P., Lofland, J., Lofland, L., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2001; pp. 136–144. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, K. Ethnographic Methods; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, C.R.; van Heugten, K.; Keeling, S. Cultural meaning-making in the journey from diagnosis to end of life. Aust. Soc. Work 2015, 68, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okely, J. Love, care and diagnosis. In Extending the Boundaries of Care: Medical Ethics and Caring Practices; Kohn, T., McKechnie, R., Eds.; Berg: Oxford, UK, 1999; pp. 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey, A. Ethnography and self: Reflections and representations. In Qualitative Research in Action; May, T., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2002; pp. 313–331. [Google Scholar]

- Referral Criteria for Adult Palliative Care Services in New Zealand. Available online: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/referral-criteria-for-adult-palliative-care-services-in-new-zealand.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2016).

- Christchurch Botanical Gardens. Available online: http://www.ccc.govt.nz/parks-and-gardens/christchurch-botanic-gardens (accessed on 26 June 2016).

- Hagley Park. Available online: https://www.ccc.govt.nz/parks-and-gardens/explore-parks/hagley-park/ (accessed on 26 June 2016).

- About CDHB. Available online: http://www.cdhb.health.nz/About-CDHB/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 26 June 2016).

- 2013 Census Quickstats about Greater Christchurch. Available online: http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/profile-and-summary-reports/quickstats-about-greater-chch/population-change.aspx (accessed on 28 August 2016).

- Lofland, J.; Lofland, L.H. Analyzing Social Settings: A Guide to Qualitative Observation and Analysis, 3rd ed.; Wadsworth: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Emmerson, R.M.; Fretz, R.I.; Shaw, L.L. Participant observation and field notes. In Handbook of Ethnography; Atkinson, A.C.P., Lofland, J., Lofland, L., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2001; pp. 352–367. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, P.; Dyck, I. Journeying through M.E.: Identity, the body and women with chronic illness. In Embodied Geographies: Spaces, Bodies and Rites of Passage; Teather, E.K., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 154–174. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, M. Being-in-the-market versus being-in-the-plaza: Material culture and the construction of social reality in Spanish America. Am. Ethnol. 1982, 9, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gennep, A. The Rites of Passage; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, C.R. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes; University of Canterbury: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Froggatt, K. Rites of passage and hospice culture. Mortality 1997, 2, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, M. Being and Time; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

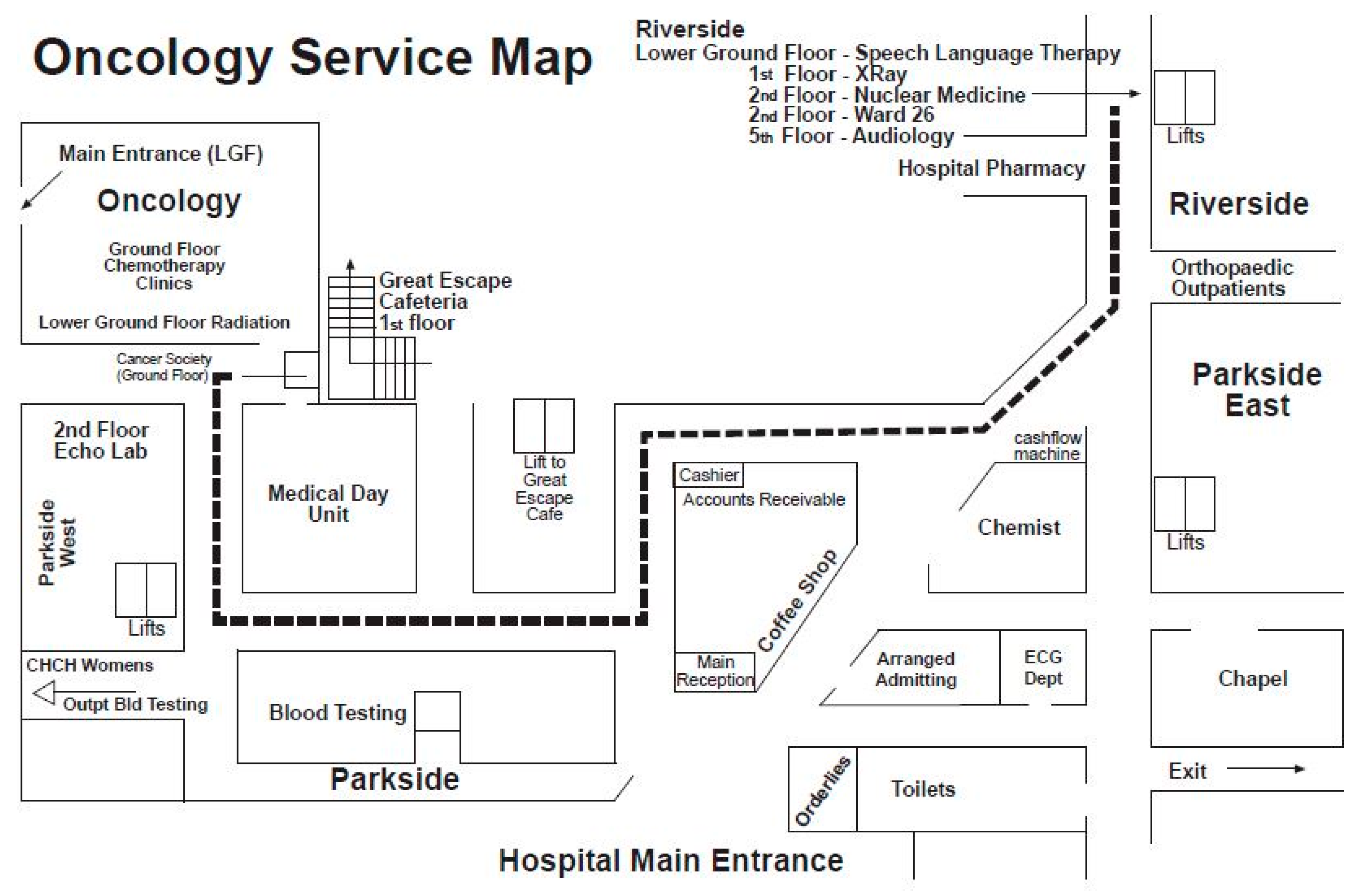

- Oncology Service Location Map. Available online: http://www.cdhb.health.nz/Hospitals-Services/Cancer-Blood-Services/Canterbury-Regional-Cancer-Blood-Service/Medical-Oncology/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 28 August 2016).

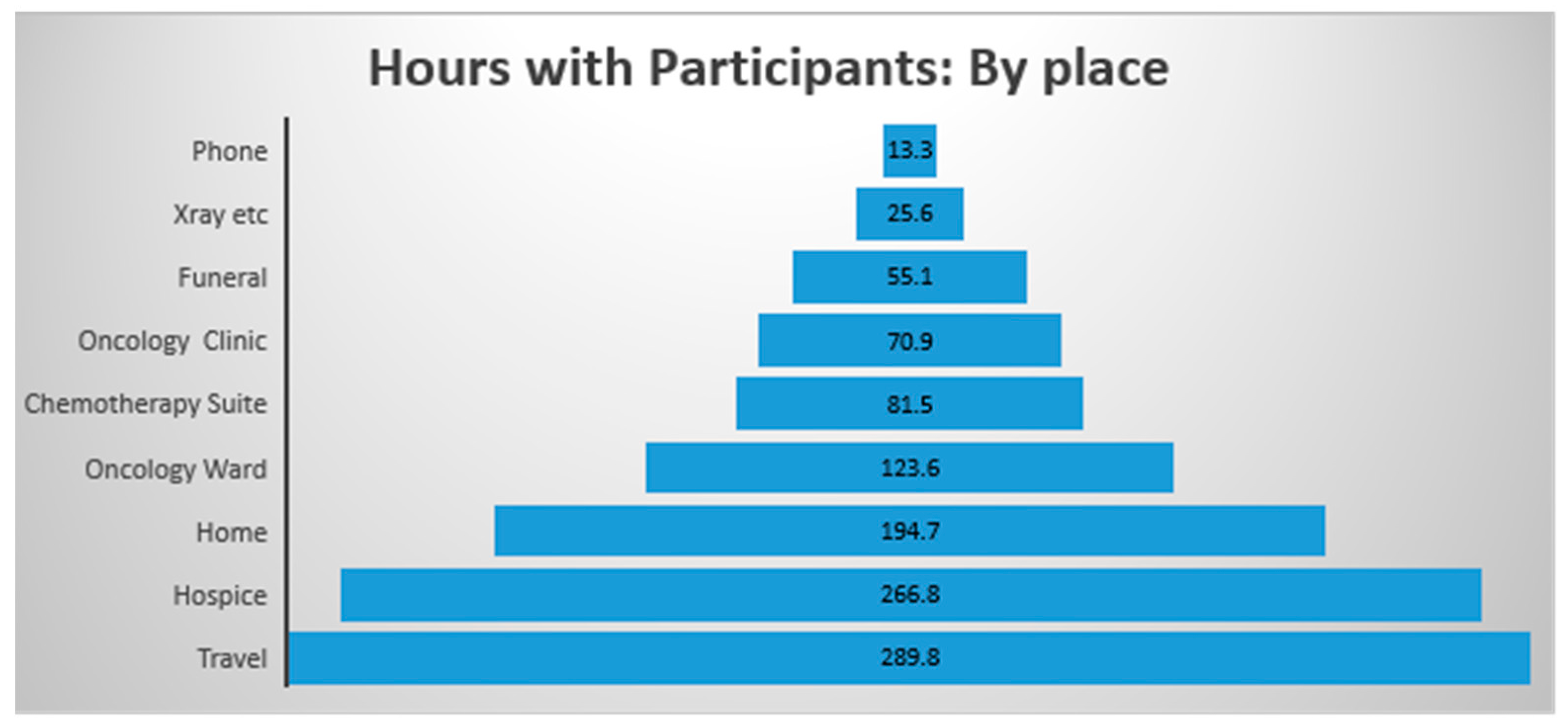

| Participant | Phone | Home | Oncology Clinic | Chemotherapy Suite | X-ray etc. | Oncology Ward | Local Hospice | Funeral | Travel | Sub-Total | Writing up | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact Time | Data Collection | |||||||||||

| 1 | 57 | 1037 | 715 | 0 | 365 | 1530 | 0 | 120 | 1490 | 5314 | 4641 | 9955 |

| 2 | 85 | 1155 | 150 | 1350 | 0 | 1865 | 0 | 720 | 2220 | 7545 | 7282 | 14,827 |

| 3 | 62 | 481 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 150 | 753 | 1326 | 2079 |

| 4 | 135 | 3760 | 2520 | 2154 | 1170 | 2765 | 135 | 1095 | 5640 | 19,374 | 15,244 | 34,618 |

| 5 | 45 | 2419 | 270 | 1385 | 0 | 140 | 0 | 120 | 2480 | 6859 | 7386 | 14,245 |

| 6 | 45 | 890 | 120 | 0 | 0 | 1055 | 0 | 120 | 980 | 3210 | 2934 | 6144 |

| 7 | 320 | 1800 | 480 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15,510 | 900 | 4220 | 23,230 | 33,294 | 56,524 |

| 8 | 50 | 140 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 360 | 240 | 205 | 995 | 1090 | 2085 |

| 799 | 11,682 | 4255 | 4889 | 1535 | 7415 | 16,005 | 3315 | 17,385 | 67,280 | 73,197 | 140,477 |

| Time | Phone | Home | Oncology Clinic | Chemotherapy Suite | X-ray etc. | Oncology Ward | Local Hospice | Funeral | Travel | Sub-Total | Writing up | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact Time | Data Collection | |||||||||||

| Minutes | 799 | 11,682 | 4255 | 4889 | 1535 | 7415 | 16,005 | 3315 | 17,385 | 67,280 | 73,197 | 140,477 |

| hours | 13.32 | 194.7 | 70.92 | 81.48 | 25.6 | 123.59 | 266.75 | 55.12 | 289.75 | 1121.23 | 1219.95 | 2341.18 |

| 8-h days | 2 | 24.3 | 8.8 | 10.185 | 3.2 | 15.44 | 33.34 | 6.89 | 36.21 | 140 | 152.49 | 293 |

| 5-day weeks | 0.33 | 4.9 | 1.8 | 2.04 | 0.64 | 3.1 | 6.7 | 1.4 | 7.2 | 28.11 | 30.5 | 58.61 |

| Months | 0.08 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 7 | 7.6 | 14.6 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hughes, C.; Van Heugten, K.; Keeling, S.; Szekely, F. Being-in-the-Chemotherapy-Suite versus Being-in-the-Oncology-Ward: An Analytical View of Two Hospital Sites Occupied by People Experiencing Cancer. Cancers 2017, 9, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers9060064

Hughes C, Van Heugten K, Keeling S, Szekely F. Being-in-the-Chemotherapy-Suite versus Being-in-the-Oncology-Ward: An Analytical View of Two Hospital Sites Occupied by People Experiencing Cancer. Cancers. 2017; 9(6):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers9060064

Chicago/Turabian StyleHughes, Catherine, Kate Van Heugten, Sally Keeling, and Francisc Szekely. 2017. "Being-in-the-Chemotherapy-Suite versus Being-in-the-Oncology-Ward: An Analytical View of Two Hospital Sites Occupied by People Experiencing Cancer" Cancers 9, no. 6: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers9060064