1. Introduction

Readers of James Joyce’s works come upon a multitude of animals, birds, and insects, and this diversity holds great allure for current criticism. According to Robert Haas’s tabulation, there are “over a thousand animal images” in

Ulysses—“dogs, cats, cows, pumas, alligators, horses, whales, camels, bees, flies, elephants...” (

Haas 2014, p. 31). Haas lists the “major animal symbols” in each episode and explores their expression of “traits and forces both within and outside of his heroes Stephen and Bloom” (

Haas 2014, p. 37). Maud Ellmann, focusing on animality in the “Circe” episode, takes up a wide range of issues including human superiority over animals, “pets or

animaux familiers” like Bloom’s cat and Giltrap’s “Garryowen,” and the “foot and mouth disease” among cattle. She discusses these issues specifically to elucidate the encroachment of animals onto the anthropocentric fortress, drawing on what she calls the “beast-admiring philosophical tradition” (

Ellmann 2006, p. 76) of Montaigne, Giovannni Battista Gelli, Rousseau, and Voltaire, as well as on Jacques Derrida’s seminal work

L’Animal que donc je suis.

The plentiful supply of animals in

Ulysses has occasioned a number of previous studies analyzing and annotating individual creatures, but attention seems to be skewed toward either living animals or animal symbols. For example, almost all the favored animals to be examined in

Ulysses are symbols or appear alive, and except for cattle and the black panther, they often have owners and names—the Blooms’ cat “pussens,” “Garryowen,” a Proteus dog called “Tatters,” and the racehorse “Throwaway” in the Ascot Gold Cup race. This also may be the case with

Finnegans Wake. When Margot Norris attempts to evaluate the ecological aspect of the work, she begins her argument by questioning whether Joyce refers to an animal “as a living thing” or merely “as a symbol or figurative abstraction” (

Norris 2014, p. 528) before emphasizing the interplay between the two. Confining the concept of “animals” to living creatures or animal symbols can narrow our awareness of the diversity of animals found in Joyce’s works and underestimate the significance of many other animals that lack names, human owners, or the kind of description that makes them distinct characters. For this reason, one of the aims in this paper is to broaden such awareness by looking at minor animals which neither appear alive nor are conspicuous, but have significant roles. Joyce’s Dublin is populated not only with live animals, but also those that are dead or extinct, as well as those “reincarnated” as commodities.

1Some of these animals do not appear as living characters, but are only talked about or described in scientific and popular discourses, drawn in posters and pictures, and consumed as commodities. This study focuses on the extinct proboscideans (mammoths and mastodons), extant elephants, their tusks, and ivory, all of which are important in considering the subject of “Joyce and animals.” These can be gathered together under the rubric of

tuskers, based on the word mistakenly used by the character Boyle in

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (hereinafter

A Portrait), in which he says that an elephant had “two tuskers instead of two tusks” (

Joyce 2007, p. 37). Along with the pared fingernails reminding Stephen of Eileen’s ivory-like hands, the

tuskers serves in this paper as a useful umbrella term to observe specific aspects of the cultural, social, and commercial value of animals in the modern society in which Joyce lived.

In order to emphasize the significance of these elements of Joyce’s writing, this paper will also use the term modern animals, by which I wish to highlight the newness or conspicuousness of animals that evoke excitement, curiosity or marketability stemming from their frightening, queer, or exotic images, zoological peculiarity, and not-yet-fully controllable ferocity. These terms and the perspective they highlight is based on my assumption that the gaze to which the animals depicted in Joyce’s texts were exposed was rather different from that of today. Therefore, another aim of this paper is to “unearth” these tuskers within the discourses of the time and examine them as they are shaped by the cultural forces or by human violence. What is revealed is an important association of the tuskers with the “fearfully unknown,” the newly discovered and curiously gazed at, and the violently consumed.

“Force,” an early essay Joyce wrote at the age of sixteen and the theory of subjugation that he developed therein, will serve as a mainstay for the overall discussion, suggesting many animal-related issues as well as key terms and platforms for analysis.

Section 2 summarizes the subjugation theory and considers Joyce’s peculiar concern with the extinct mammoth and mastodon as exemplifying

the unsubjugated along with his knowledge about them at the time.

Section 3 looks at elephants, or more broadly, at “queer creatures,” as they illustrate his theory. After historicizing the experience of seeing the pachyderm exposed to curious gaze, I turn to an elephant episode in a Mullingar fragment of

Stephen Hero, which not only reveals the elephant as

the subjugated but also has a curious connection with “Force.” The last tusker to be examined is elephant tusks themselves and processed ivory as

the consumed. In the same manner that Leopold Bloom sees the donkey in a drum (the “[a]sses skin. Welt them through life, then wallop after dead”;

Joyce 1986, p. 237), here we will find the elephant in ivory. Through the gaze of Bloom, who sees “[c]ruelty behind it all” (

Joyce 1986, p. 52), the reader will obtain a different perspective of Dublin located in the broader map of the turn-of-the-twentieth century world. Finally, these tuskers will signal the author’s developing concern with animals and the theme of subjugation.

2. Joyce’s “Force” and Fear of Extinct Monsters

At first glance, one might think that Joyce had little to say about animal issues in the early stage of his writing, but my pursuit of the subject of animals in his writings brought me back to one of his earliest essays, now entitled “Force,” written in September 1898 for his matriculation course at University College Dublin. Fragmental and premature as it is, the essay should be considered the first source to examine because it concerns the subjugation or domestication of the kingdom of animals and vegetation, and even the extinction of certain species, foreshadowing several motifs developed in Joyce’s later writing. Especially useful for the purpose of this paper is that the essay mentions both extant and extinct proboscideans.

A brief outline of the essay might be necessary as it is still considered a minor work. The surviving manuscript begins in the middle of a statement that all subjugation by force produces a repetitive cycle of rebellion, violence, and bloodshed. To his argument about “an oppressing force,” Joyce adds the effective use of “influence.” The example given is the “diplomatic” use of nature or the elements, like a gardener trimming trees and shrubs into a neat garden or a sailor steering a ship using the force of the wind. Human technology, such as miller’s wheels, can harness the “fierce power” of water for commercial uses such as making flour and bread. Joyce then proceeds to the second category of subjugation, the domestication and taming of animals, which he describes as the human mission since the time of Adam, and then to the third subjugation of other races by white men, “the predestined conqueror” (

Joyce 1959, p. 20). One-half page is missing, and then Joyce introduces another form of subjugation, the control of a great artistic gift. Having pointed out the virtue of controlling prolific or explosive imagination and the benefit of avoiding extremes, he moves to the topic of subduing passion and reason, and somewhat abruptly reaches his conclusion: “The essence of subjugation lies in the conquest of the higher” (

Joyce 1959, p. 24). The desire to overcome

the higher is inherent in the human spirit, Joyce argues, and it can flourish politically in imperialism or national issues, and individually exercise “a great influence.” His long-winded style, compounded by the missing sections, makes his conclusion rather obscure, but considering his concern about the vicious cycle of oppressive forces and violence, the last sentence of the essay seems to welcome power, persuasion, and kindness as a new form of subjugation.

Let me examine the second category of subjugation more in detail. Here Joyce starts his argument from the opening of human mastery over animals beginning with Adam’s mission in Eden where “every animal,” including even the lion, “was his willing servant.” After Adam disobeyed his Creator by committing the sin, however, “the unknown dregs of ferocity” spread among the beasts, changing them from friendly servants to bitter enemies, and thereafter humans were destined to struggle against them for superiority (

Joyce 1959, pp. 18–19). Successful domestication can be seen in the case of dogs guarding their owner’s property or horses and oxen working as farming or industry draft animals. Yet among the beasts, some could not be subjugated, and the young author here names the mammoth and the mastodon.

The Zoo elephants are the sorry descendants of those mighty monsters [mammoth and mastodon] who roamed in hordes, tameless and fearless, proud in their power, through fruitful regions and forests,...who spread themselves over whole continents and carried their terror to the north and south, bidding defiance to man that he could not subjugate them; and finally in the wane of their day, though they knew it not, trooped up to the higher regions of the Pole, to the doom that was decreed for them. There what man could not subdue, was subdued, for they could not withstand the awful changes that came upon the earth.

“[T]he lord of the creation,” Joyce suggests, seemed to protect human dignity from

the unsubjugated, “the fear of mammoth and of mastodon,” driving the great beasts to extinction in the “unkind” climates of frigid regions. Joyce then envisions the remnants of their bodies as they appeared in the New Siberian Islands where “colossal tusks and ivory bones are piled up in memorial mounds” (

Joyce 1959, pp. 18–19).

2 He describes how they were doomed to utterly awful and complete subjugation, vanishing from the earth with no trace save for their fearful tusks, which were destined to be greedily gathered up as lucrative commodities. He concludes his explanation of the second category of subjugation by saying that all common animals are subjugated to human force, and that even those that are now free from human mastery will eventually be driven out of their habitats and threatened with extinction like the American bison. He described how domestic cats, the despised pig, poisonous snakes, lions with their spirits broken in shows and circuses, and “the ungraceful bear” in the streets—all are cowed into proving the power of man.

Strangely, “Force” has been slipping away from critical attention, perhaps because of the youth of the author when it was produced or the fragmental quality of the manuscript. Indeed, Mason and Ellmann note its immaturity, saying “he [Joyce] had not yet liberated his language, and could still use conventional rhetoric in a classroom exercise” (

Joyce 1959, p. 17). Notwithstanding, it can be argued that the essay provides a major source for speculation on the significance of animals in Joyce’s works, especially to gauge his early knowledge and concern with animals. Below, I discuss his reference to mammoths and mastodons as “what man could not subdue” and examine what constitutes the

fear and

terror in these extinct creatures.

The iconic imagery of mammoth and mastodon is by now rather familiar, but they were long shrouded in mystery. It was not until around 1800 that the concept of extinction was established in George Cuvier’s treatise

Mémoires sur les espèces d’éléphants et fossils, what Claudine Cohen calls “the cornerstone of scientific paleontology” (

Cohen 2002, p. 106). Cuvier proved on the basis of comparative anatomy that Indian and African elephants do not belong to the same species, and that the fossils of the Siberian mammoth and the mastodon found in America were distinct from two surviving species of elephants, for the first time offering crucial evidence of the phenomenon of extinction. The impact of Cuvier’s writings and his principle of the correlation of parts was so great that the idea of extinction merged in the romantic imagination, making Honoré de Balzac in his La Peau de chagrin (1831) call Cuvier “the great poet of our era,” who “has reconstructed the past worlds...and has rebuilt cities [i.e., lost worlds populated with prehistoric creatures]” from monster’s teeth and bones (

Cohen 2002, p. 121).

By 1800 many kinds of huge, unspecified fossils had been unearthed in the vast frigid-zone areas of Siberia, northern parts of Europe, and America, but discoveries of mere bones and teeth without remains of bodies stimulated mainly fear, excitement, and curiosity, spinning superstitions and producing inaccurate restorations as well as faulty hypotheses. In the New World, for example, the mastodon was known as an

incognitum and considered to be carnivorous judging from the bumpy molar teeth that were excavated, and was even envisioned to have “claws” (

Semonin 2000, pp. 288–314). The unknown animal thus signified “a symbol of both

the violence of the newly discovered prehistoric world and the emerging nation’s own dreams of an empire in the western wilderness” (

Semonin 2000, p. 3; emphasis mine). The American Founding Father Thomas Jefferson, famously counters Buffon’s assertion of a degenerated America, denying the concept of extinction and siding with the belief that the extinct animal “still exists in the northern and western parts of America” (

Jefferson 1984, pp. 165, 176–77).

3 Even if it was extinct, some believed “it was providentially so because God had cleared those dangerous animals away to allow the nation to prosper” (

Nance 2013, p. 22;

Semonin 2000, pp. 264–65). Interestingly, the American discourse echoed in young Joyce’s description of extinction by the “lord of the creation,” a forced effort to include the newly discovered prehistoric creatures in the existing epistemological framework.

Of the two extinct animals, it is mammoths that Joyce seemed to find most fearful. Mammoths, in fact, had been embellished with ominous and horrible images. Some natives in Siberia called the supposed animal “Momont” or “Mamot,” and believed that it looked like a big rat living underground and avoiding sunlight, and that exposure to light caused it to die. In addition, the “holy terror” inspired by their excavated remains was enough at the time to discourage the cossacks from hunting their tusks (

Cohen 2002, pp. 65–66).

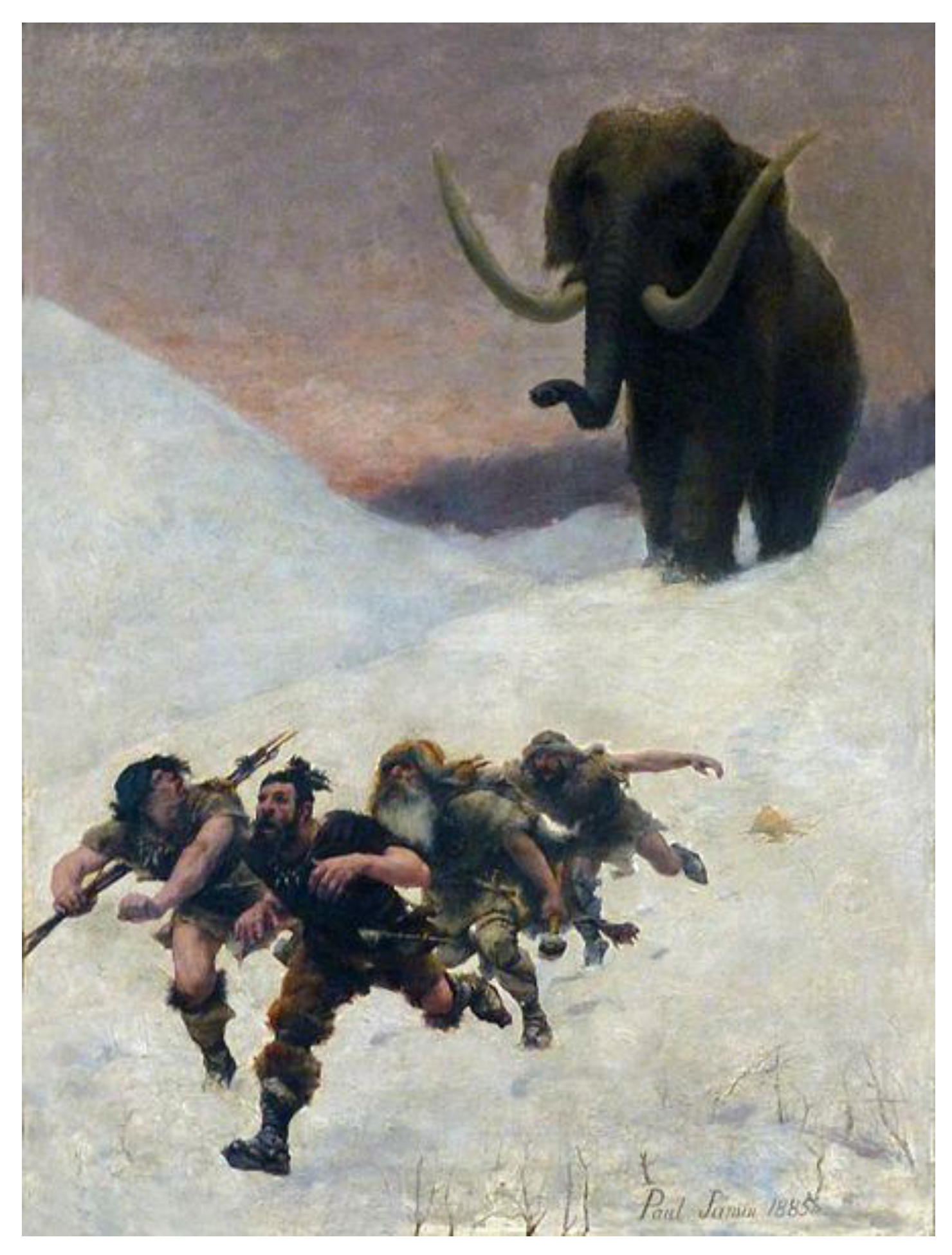

4 The fear was dramatic in its representation when the huge remains of their bodies and colossal tusks were unearthed in the permafrost. Based on the specimen that was discovered in 1799 near Lena River in Siberia (wrongly reconstructed with regard to the direction of the tusks), the French painter Paul Joseph Jamin made a sketch version,

Le Mammouth (1885), and a painted version,

La Fuite devant un mammouth (1906), which depicts four hunters desperately fleeing from an approaching mammoth in the snowy hills (

Figure 1). The “sense of desolation and terror” (

Cohen 2002, pp. 1–2) emanating from the giant quadrupeds illustrates the way Joyce defines in “Force” the two monsters as those “who...carried their

terror to the north and south, bidding defiance to man that he could not subjugate them” (

Joyce 1959, p. 19; emphasis mine). It seems likely that Joyce’s fear of the prehistoric animals was colored by popular discourse at a time when the whole picture about them had yet to be brought to light. At least to the sixteen-year-old student, the mammoth and mastodon were what a human “was not able to make his slaves when they lived,” and a symbol of

the unsubjugated.

Significantly, he did not forget his fear of these creatures. They reappear in “Oxen of the Sun” in

Ulysses as the vengeful “ghost of the beasts”:

Elk and yak, the bulls of Bashan and of Babylon, mammoth and mastodon, they come trooping to the sunken sea, Lacus Mortis. Ominous revengeful zodiacal host! They moan, passing upon the clouds, horned and capricorned, the trumpeted with the tusked, the lionmaned, the giantantlered, snouter and crawler, rodent, ruminant and pachyderm, all their moving moaning multitude, murderers of the sun.

A march of the mighty; compounded by Bloom’s concern about “cows that are to be butchered along of the plague [foot and mouth disease]” (

Joyce 1986, p. 326), and embellished by a De Quincy-like phantasmagorical style

5 as well as a Homeric parallel of this episode, the passage brings the cattle heading for Liverpool that Bloom saw in the daytime into an imagery of merciless slaughter. Mammoths and mastodons are conjured up in an ominous vision of slaughter on a greater scale, the “unkind” extinction that can be considered Joyce’s enduring anxiety about violent force and

the unsubjugated. Here “Force” turns out to be not simply the idle scribbles of a young student, but something in the process of developing. If we regard the style as “[c]onventional rhetoric in a classroom exercise,” his incipient concern with animals would be overlooked. Among the key terms that we have so far “unearthed” and purveyed are subjugation, domestication, extinction, terrible prehistoric creatures, greed for ivory, and the New Siberian Islands; these will be further examined and connected with each other in the following sections.

3. Elephants, or Queer Creatures, as the Subjugated

Harriet Ritvo’s influential book

The Animal Estate is devoted to a detailed analysis of the aspects of human-animal relationships that experienced radical change in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; she deals with scientific stock and pet breeding, the rabies panic, the English anti-cruelty movement, zoos as imperial institutions of domination, and big game hunting (

Ritvo 1987). The historical approach in her investigation on animal-related rhetorical strategies and metaphors is helpful for understanding how the elephant was represented in themes of domination and exploitation in the Victorian age. Among the natural history and popular zoology discourses on animals she quotes, there is a summary of one writer’s comment: “The ‘perfect subjugation’ of the elephant by ‘a creature so inferior in bodily strength as man’ was a powerful confirmation of the natural hierarchy, in which the human ‘head and hand subdue all living things, however enormous, to his will’” (

Ritvo 1987, p. 25). The pachyderm was easy prey to the urge to prove mastery, superiority, and manliness, being the ultimate game in the sport of hunting (

Rothfels 2007), the super-star of circuses (like the celebrated “couple” of Jumbo and Alice;

Joyce 1986, p. 273), or the lucrative cynosure of menageries and zoos. Therefore, when Joyce pities the zoo elephants as “sorry descendants” of extinct fearful proboscideans, and remembers “broken-spirited lions” in “shows and circuses before large crowds,” he recognizes the modern forces of exhibition (

Joyce 1959, pp. 19–20). Here let me examine elephants as

the subjugated. After historicizing the experience of “seeing elephants” in the nineteenth century, we discover how the subjugation theme emerges in an elephant episode in

Stephen Hero.

Once again, it is better to bear in mind the risk of projecting what we see today onto a text produced a century ago. A short poem of recent authorship entitled “At Dublin Zoo” by Irish Poet Paula Meehan, included in

Painting Rain (2009) (

Meehan 2009, p. 18), highlights the contrast with seeing elephants in the Victorian age.

- A four-year-old

- Seeing elephants

- For the first time

- ‘But they’re not blue.’

The poem portrays a twenty-first-century child’s first experience of seeing an elephant in the zoo at the Phoenix Park (first established in 1831 as Zoological Garden Dublin; hereinafter “Dublin Zoo”). Into the blank space in the middle is inscribed the cognitive fissure that mercilessly severed the actual and the surrogate, bringing home the child’s disappointment that the color of an actual elephant is not blue—perhaps, neither the beautiful blue in a picture book nor the blue with which it was recreated in drawings. Seeing actual animals, after having first been exposed to their surrogates, may be a crucial experience that could be shared across time. We will recall the little boy who in

A Portrait once enjoyed the “moocow” in a fairy tale, grew up to change not only the way he saw the animals but also its products: “the first sight of the filthy cowyard at Stradbrook...sickened Stephen’s heart. The cattle which had seemed so beautiful in the country on sunny days revolted him and he could not even look at the milk they yielded” (

Joyce 2007, p. 55). However, what is important in reading Meehan’s poem is to recognize the fact that in the nineteenth century,

seeing elephants for the first time meant something completely different.

Susan Nance, in her excellent book on the heyday of the American circus-elephant industry (1796–1907), emphasizes the initial novelty of seeing elephants. For example, when a ship named

The America carrying the first elephant to come into the United States arrived at port on April 1796, a New York newspaper reported under the headline: “

The America has brought home an ELEPHANT, from Bengal, in perfect health. It is

the first ever seen in America and a great curiosity,” and the reason for the novelty was that “in all probability,

almost no one in the country knew in detail what a wild young elephant looked, moved, or sounded like” (

Nance 2013, p. 20; emphasis mine).

6 The curiosity to see the modern animal was also shared in London and Dublin. Lord Byron noted in a November 1813 diary entry the regular trick performed by the intelligent animal in a menagerie at Exeter Change (

Byron 1982, p. 84). At the London Zoo in the 1850s, an elephant calf from Calcutta attracted attention, since “so small an elephant had rarely been seen in Europe” (

Ito 2014, pp. 121–22). Meanwhile, the first elephant to appear in the Dublin Zoo arrived in 1835, on loan for £100 a month from a travelling animal keeper. After that, several elephants were housed in the Albert Tower (set aside to house exotic animals), and their popularity was tremendous. An elephant on loan from a circus that stayed during only the summer months in 1871 was said to attract “huge numbers of visitors” (

De Courcy 2009, p. 49). What is notable is that their newness or conspicuousness was so consumable. Robert W. Jones describes the strategies of zoos in the Victorian age as wedded to the British imperial endeavor in displaying “the sight of creatures strange to our clime and notions”; the exotic animals became commodities displayed “to be looked at, to be consumed, as a sign of pleasurable difference” (

Jones 1997, p. 11).

7 The pachyderm on exhibition is only a de-tusked beast. In fact, at the Dublin Zoo, the points of the elephant tusks were capped so that they could not hurt the visitors and trainers. See photographs in

De Courcy (

2009, pp. 16, 66).

As for seeing an elephant in Dublin, another example would be of interest to Joycean readers. When the funeral carriage “in Hades” moving along Sackville street passes the two statues of Daniel O’Connell and Sir John Gray, Bloom and others see the figure of Leuben J. Dodd “stumping around the corner of Elvery’s elephant house,” (

Joyce 1986, p. 77). Elvery’s was Ireland’s oldest sports shop, founded in 1847 or 1850,

8 and dealing in waterproof clothing and sportswear. One other statue that the occupants of the funeral carriage must have been able to see may well be mentioned. Brenda Malone’s blog (

Malone 2013), which displays objects and photographs from the Historical Collections of the National Museum of Ireland, shows us that Elvery’s building once had a rubber statue of an elephant above the front door.

9 As to this sculpture, an intriguing 1954 article in the

Irish Times reports on the origin of the “elephant house”:

As far as the origin of the name is concerned, there are several stories in existence. The most widely accepted one is that the building got its name from a tea importer’s shop which used to be either next door to the present building, or in the building itself. This enterprising tea importer attracted visitors to his shop, they say, by keeping a live elephant in it. The elephant was, it seems, a retired circus animal, and accounts differ on the question of whether the tea importer charged admission to view it, or whether it was simply a publicity stunt. At any rate, when Elvery’s bought the building, so the story goes, it was already known to Dubliners as Elephant House, and the firm decided to retain the name and give it official backing by building a statue of an elephant over it.

Considering that its business was selling durable rubber goods like galoshes and mackintoshes, Elvery’s elephant sculpture would have been entirely suitable in light of its catchy alliteration and the marketing function the elephant icon had acquired by then (

Nance 2013, pp. 20–21). Notable here is the cultural aspect of seeing an exotic animal at the time. The elephant remains exposed to curious gaze, first when performing in the circus, then before the crowds visiting the tea importer’s shop, and finally is

reincarnated into a rubber sculpture: it exists to be seen—always serving as a commodity to catch the eye, in life and after death.

Having pointed out the novelty of the elephants, I would now like to move on to an episode included in

Stephen Hero (

Joyce 1963, pp. 242–45) that underpins the points observed above. The extant parts of the novel, set in a period of Stephen’s university life around 1898–99, consist of several pages (supposed to be Chapter XIII) describing his short trip to a village in Mullingar in County Westmeath, a suburban rural area to the northwest of Dublin. There, Stephen has a chance to listen to an officer named Captain Starkie narrate a “humorous episode.” One day, the officer and his friend, “a learned young lady,” seeking cover from rain, find shelter in the cabin of an old peasant. While drying herself before the fireplace, the woman notices an unintelligible chalk scrawl on the wall and asks the old man what it is. He explains that it is a drawing by his grandson Johnny. The old man explains that the boy saw a circus poster on the walls in the town, and went to the venue “to see th’ elephants.” To his disappointment, however, there was no elephant in the circus, and the boy came home discouraged and drew a scribble of the animal instead. The old man then proceeds to talk about the genial, even pious quadrupeds, and compares the tasks of imposing discipline upon elephants and children:

“I’ve heerd [heard] tell them elephants is most natural things, that they has the notions of a Christian

10...I wanse [once] seen meself a picture of niggers riding on wan[one] of ‘em-aye and beating blazes out of ‘im with a stick. Begorra ye’d have more trouble with the children [sic] is in it now that with one of thim [them] big fellows.”

Amused by the tale, “the learned lady” shows her knowledge of “the animals of prehistoric times,” and then the old man replies with his surprise: “—Aw, there must be terrible quare craythurs [queer creatures] at the latther ind [latter end] of the world.” Stephen praises the punchline and joins in the laughter at the ignorance of the old man who still believes—like Thomas Jefferson—that prehistoric animals survive on the earth. Meanwhile, indignant Mr. Fulham, Stephen’s nationalist godfather, insists that Irish peasants should have a truer ideal of the Christian life than Captain Starkie, calling them “the backbone of the nation.”

11 The word “backbone” gives Stephen the chance to insert his derision of the physical traits of the peasants in Mullingar, but, at the same time, they are portrayed as also gazing at the young man with metropolitan features “as if he were some rare animal.” This episode is immediately followed by another incident of a lame beggar with a stick, who threatens the children with curses. The beggar’s malicious visage reminds Stephen of those “pandied” boys and the prefects with broad leather bats in Clongowes Wood College; especially the beggar’s “sharp eyes” leave him with “a fine chord of terror” (

Joyce 1963, pp. 242–45).

Reading “Force” before revisiting this episode, narrated in just four pages, sheds light on so-far invisible themes. One of the themes is subjugation by means of one disciplinary stick or other. That the grandson could not see an elephant and ended up drawing its surrogate sustains the novelty of the animal and its cultural status exposed to a curious gaze. The drawing reminds the old man of “a picture of niggers riding on” elephants beaten by a

stick (or maybe “a hendoo,” the hook-like implement wielded by a mahout), which he immediately links to the disciplining of one’s child. One page later, the sharp-eyed beggar intimidates the children with his

stick, saying “I’ll cut the livers and the lights out of ye.” This evokes the castrating eagle and the voice in

A Portrait (

Joyce 2007, p. 6) repeating “[p]ull out his eyes,” foreshadowing the theme of subjugation. In fact, the beggar’s malicious expression reminds Stephen of another “civilizing”

stick, the punishing pandybats and floggings of his school days. Here Joyce connects the subjugation of animals to that of children, juxtaposing the images of the elephant beaten with a stick and Stephen on his knees being beaten by the pandybat as one among

the subjugated.

This theme of subjugation also unveils the unsubjugated in the conversation carried on in the old man’s cabin. When Johnny’s drawing reminds the learned lady of “animals in prehistoric times,” the old man’s replies to her, saying that “terrible quare craythurs” still survive in “the latther ind [latter end] of the world.” We who have reread “Force” have ample reason to believe that what the woman and the old man are talking about is the fearsome mammoths (which she might have referred to as untamable with a stick). And the specific location of “the latther ind [latter end] of the world” is presumably some islands near the North Pole, or possibly the New Siberian Islands. The adjective “terrible” that the old man used to describe the animals echoes Joyce’s terror explained in the previous section, and “quare craythurs” is loosely related to the “rare animals” mentioned soon after, making both the elephants and Stephen exposed to curious gaze. Thus, “Force” illuminates the references to the more “terrible tuskers” that appear in Stephen Hero.

4. Ivory as Colonial Commodity

The last section is also concerned with seeing, but more specifically, with the perspective to see elephant tusks and ivory. It is no doubt that “the white thing” plays a significant role in

A Portrait, serving to evoke Stephen’s memory and senses. The soft-hued, white, smooth, and cold texture of the material, and the easily rhymed sound of the word are employed to express the hands of Eileen and Emma and the thighs of the bird-girl on the seashore. Stephen’s earlier repulsion of real cows and the milk they yield (

Joyce 2007, p. 55) may have prompted him to prefer metaphysical to physical ivory, as manifested in his search for poetic diction: “The word [ivory] now shone in his brain, clearer and brighter than any ivory sawn from the mottled tusks of elephants” (

Joyce 2007, p. 184). This is ivory processed for poetry so that the elephants killed for the purpose can be rendered invisible. What this section will try to do, on the contrary, is to see ivory as the very material “sawn from the mottled tusks of elephants.” Leopold Bloom, as noted in the introduction, is the character that offers us this gaze. He reflects on the vegetarian advice not to eat beefsteak, warning that you will be followed by “the eyes of that cow.” And seeing branded cattle brings to his mind their slaughter and byproducts: “Roastbeef for old England...all that raw stuff, hide, hair, horns...Dead meat trade. Byproducts of the slaughterhouses for tanneries, soap, margarine” (

Joyce 1986, p. 81). His gaze goes beyond what he sees before his eyes, and penetrates beneath what is on the surface. Especially in the case of animals, he sees “[c]ruelty behind it all” (

Joyce 1986, p. 52). The aim of this section is to see what is behind the ivory products that appear in Joyce’s novels.

In

A Portrait, young Stephen recalls Eileen’s hands: “...long and white and thin and cold and soft. That was ivory: a cold white thing” (

Joyce 2007, p. 31). Such descriptions presuppose that he previously had the experience of touching ivory products. Unlike today, when there are few chances to touch a material now banned in international trade, a wide variety of ivory goods were part of daily life. For example, an 1882 article “The World Ivory Trade” that appeared in the

New York Times—the year when Joyce was born—mentions the differences among Indian and East/West African ivory and lists various common ivory items.

The differences which exist in the quality and color of various assortments of ivory are great, and vary according to the producing country. Not only is there a marked difference between Indian and African Ivory, but East African ivory is readily distinguishable from West African. East African ivory, known in the trade as “soft, white ivory,” is the product of Eastern Africa from Egypt down to the Cape. It is particularly well adapted for use in the manufacture of piano-forte keys, billiard balls, and combs...The coarser variety of ivory from these regions is chiefly used for knife, cane, and umbrella handles, while the finer portions are used for prayer book covers, the backs of brushes, and fans.

It is tempting to imagine that either Dante’s two brushes or the knife with (not yet broken) ivory handle is the item from which Stephen had learned what ivory is (

Joyce 2007, pp. 5, 14, 142). But the most likely item will be the piano keys in the Dedaluses. Several words indicate the close relationship among hands, ivory, and the instrument. In chapter five, when Stephen plays “chords

softly from the

speckled piano keys” in Emma’s house, his hands seem to remember “a

soft merchandise,” i.e., “her hand lain in his” during the carnival ball (

Joyce 2007, p. 193; emphasis mine). In fact, certain adjectives match the characteristics of “tripy ivory,” as it is called in trader’s parlance, which, Clive Spinage explains, is ivory with “a mottled or speckled appearance” as the sign of a deficiency [of calcium] (

Spinage 1994, p. 220).

Ivory products depicted in a novel set at the turn of the twentieth century merit special attention. Based on the data of Martin and Vigne (1989), Raman Sukumar gives a graph plotting the two centuries from 1803–1986, showing the annual quantity of ivory that India imported (

Sukumar 2003; see the top graph, Figure 8.11 on p. 335).

12 While the quantity for the period of the 1800s-70s fluctuated between almost 200 to 400 tonnes, the figures show the literally skyrocketing increase in the period of the 1880s to 1900s from 800 to 1200 tonnes, suddenly plunging to approximately 100 tonnes at the end of the 1900s. What was happening in that period? Sukumar explains the sharp rise by ascribing it to the new regime in Africa: “the volumes of ivory emanating from Belgian Congo were especially large at 352 tonnes per year (during 1888–1909), representing about half of Africa’s total exports at this time” (

Sukumar 2003, p. 333).

As has been well documented, the Congo Free State was governed by the cruelest of methods. King Leopold II of Belgium, after elaborate preliminary investigations in the name of “humanitarian” philanthropy and under the flag of the International Association of the Congo (with yellow star representing civilization against a blue background signifying the dark continent), founded the Free State in 1885, and the private colonization of what was still

terra incognita to Europeans at that time began. In 1888, in order to exploit Congolese natural resources, the king set up the

Force Publique, which organized the systematic use of indigenous forced labor for the supply of what was soon to be explosive demand for rubber to make pneumatic bicycle tires. As their atrocious deeds are told in the “Cyclops” episode, the soldiers were not only “[r]aping the women and girls and flogging the natives on the belly to squeeze all the red rubber they can out of them” (

Joyce 1986, p. 274), but also mutilating body parts (including genitals) as punishment for unsatisfactory fulfilment of quotas imposed on them. But what symbolized the atrocities in the Congo most was “severed hands,” which “served as proof that the

Force Publique soldiers were doing their job” and even “became a sort of currency” (

Forbath 1977, pp. 373–75;

Hochschild 2012, pp. 164–66). This colonial regime was soon to be denounced by journalists and writers, as seen in George W. Williams’s “An Open Letter” to Leopold II (1890), Joseph Conrad’s three-parts serialization of “The Heart of Darkness” (1899) in

Blackwood’s Magazine, E. D. Morel’s

King Leopold’s Rule in Africa (1904) and

Red Rubber (1906), Roger Casement’s report (1904), Mark Twain’s

King Leopold’s Soliloquy (1905), Conan Doyle’s

The Crime of the Congo (1909), and other works. The appearance of these works of the anti-Congo movement makes more significant the year 1904 setting of the world of

Ulysses, in which Father Conmee keeps an “ivory book mark” in his red-edged breviary for ecclesiastical use, and Phantom Rudy wears a suit with diamond and ruby buttons and has “a slim ivory cane,” showing the symbolic trappings of the wealthy (

Joyce 1986, pp. 184, 497).

While “red rubber” was the most infamous item in the Congo regime, ivory continued to be the most profitable item exported by the Free State until the mid-1890s. In fact, consumption of ivory for a variety of uses in the latter half of the nineteenth century was so lavish that extinction of the African elephant became a matter of international concern. As the above-mentioned figures attest, the major reason for its endangerment was the exports of the Congo Free State. An article in the

Irish Times in June 1897 warned of the probable extinction of elephants, quoting an expert as saying, “[a]t present the natives, actuated by the high price for ivory or by the cruelties of Belgian officials, devote themselves more and more to elephants hunting” (

Anonymous 1897). The following year, the

New York Times reported on the same issue with the striking title of “To Save the Elephants: The African Animals Nearly All Killed off by the Ivory Traders—Their Brutal Massacre...,” and predicted that the merciless slaughter of the tusker in the Congo would lead to its extinction “in less than ten years” (

Anonymous 1898). In this regard, Conrad did not exaggerate in creating ivory-obsessed character Krutz, inscribing the image of the volumes of stacked ivory so copious that “[y]ou would think there was not a single tusk left either above or below the ground in the whole country” (

Conrad 1988, p. 49). Krutz’s “appetite for more ivory” (

Conrad 1988, p. 57) itself is an example of a greedy force driving elephants to the verge of extinction. Seeing this tremendous consumption of tusks and ivory in the period through Bloom’s gaze at the “[c]ruelty behind it all,” the goods so commonplace in Joyce’s texts—”knife handles, billiard balls, combs, fans, napkin rings, piano and organ keys, chess pieces, snuffboxes, brooches, and statuettes” and even “false teeth” (

Hochschild 2012, p. 64)—may look rather different. Though it is not written whether or not the items are made of ivory, they now signal the reader to imagine the tusker and the violence that was perpetrated to produce them.

At sixteen, Joyce wrote about the greed for wealth that drove people to the New Siberian Islands in search of the ivories of extinct mammoths, although he probably did not know at the time what was happening to the Congolese population and its elephants; it would be a few more years until he learned of those atrocities. Instead, the 1898 essay includes the bigoted definition of white men as the “predestined conqueror,” which, as Vincent Cheng points out, was “a product of the racist discourse of nineteenth century white, European culture” (

Cheng 1995, p. 15): the very notion that justifies white supremacy to enlighten “the horror of savage unrule” (

Joyce 1959, p. 22), echoing the rhetoric of the “humanitarian” policy of King Leopold II. Although the young Joyce denounces the system as the worst form of subjugation, his assumption itself would have been frowned upon by the older Joyce, or by Bloom, who belongs to a race “that is hated and persecuted” and who “resent[s] violence and intolerance in any shape or form” (

Joyce 1959, pp. 273, 525). Yes, Joyce was partly wrong. Just as he was writing in Dublin the optimistic sentence assuming that “nor any longer does he [the white race] or may he practice the abuse of subjugation—slavery,” the colonial regime was forcing Congolese people shackled at the neck to work and slaughtering elephants to the point that their species became endangered. It was almost ten years later that the subjugation theory he first devised in 1898 would be somewhat updated or amended. In one of three lectures that he delivered at the Università Popolare Trieste in 1907—the year just before King Leopold II relinquished his private ownership of the State—he stated “…for so many centuries the Englishman has done in Ireland only what the Belgian is doing today in the Congo Free State” (

Joyce 1959, p. 166), enunciating one of the recurring subjects of his later novels.

5. Conclusions

By revisiting Joyce’s “Force” and utilizing his subjugation theory, this paper has demonstrated a way to locate minor animals in Joyce studies and examine their significance in the historical context and in the discourse of the time. As observed in the first section, Joyce’s reference to the extinct, and fearful mammoth and mastodon monsters is never whimsical but is an indication of his concern about extinction and his anxiety about what human beings cannot subdue. Meanwhile, he was aware of the forces being inflicted upon the proboscideans of his time. As I have illustrated, elephants were once a rarity and a cynosure in circuses and zoos, and even a shopping establishment like Elvery’s heavily preyed upon them with the curious gaze of shoppers and exhibition-goers. This analysis allows us to see Joyce’s recurrent theme of his subjugation theory, which not only connects the episode in Stephen Hero to “Force,” but also discovers the “terrible tuskers.” As the final tusker, section four looks at ivory as a colonial commodity. Normally, the raw materials from which consumer goods are made leave scant trace of the living creatures from which they came, and therefore are hardly recognizable as animals. However, with an attempt to “unearth” such buried items, the section employs Leopold Bloom’s gaze to expose the greed of the King Leopold II’s imperial system, its cruelty to the Congolese population and to elephants, and the all-too-violent consumption of ivory. What is betrayed there is the human greed for more and the violence that causes certain species of animals to be extinguished. Through these analyses, we can now see the mammoth and mastodon as the unsubjugated, elephants as the subjugated, and ivory as the consumed, each revolving around modernity, and gravitating toward each other to form the constellation of “Joyce’s tuskers.”

Joyce failed to predict the future of the slavery system, and yet his insight into the phenomenon of extinction and the insatiable desire for the subjugation of the higher turns out to be valid today, and it is helpful in detailing

modern animals. We will recall the dinosaurs, “the terrible lizards,” in film

Jurassic World (2015), where the DNA scientists possess the advanced technology of de-extinction for resurrecting lost species and create new creatures by genome editing to attract more visitors. At the beginning of the film, recollecting the excitement of the days of

Jurassic Park (1993), operations manager Claire Dearing points out the new demand on the park and introduces their cutting-edge method to the funders:

...no one is impressed by a dinosaur anymore. Twenty years ago, de-extinction was right up there with magic. These days, kids look at a Stegosaurus like an elephant from the city zoo...consumers want them bigger, louder, more teeth. The good news? Our advances in gene splicing have opened up a whole new frontier.

Note the indifferent gaze of the children, not at Stegosaurus, but at elephants. Consumers’ or visitors’ desire

for more renders the animal that was the star two centuries before a mediocre creature. What the scientists created instead is

Indominus rex (“untamable king”). The contradictory name given to the product of that desire would endorse Joyce’s formula: “[t]he essence of subjugation lies in the conquest of the higher” (

Joyce 1959, p. 24). As the terrible lizard-like creature exemplifies,

modern animals are those that are newly discovered or newly focused on by the society and members within, and therefore show the use of newness or conspicuousness to mirror the desire or mentality of people of a certain time.

Considering that Joyce mentions the endangerment of the American bison and the phenomenon of extinction, and ascribes the disappearance of mammoth and mastodon to both “the lord of creation” and the cold climate, “Force” may be able to attract more critical attention in view of the recently popularized notion of the “Anthropocene,” the newly proposed geological epoch when human beings have become the telluric force that changes the natural environment or entire Earth’s system (

Bonneuil and Fressoz 2017). As unstable and disputable as the definition of Anthropocene is, the idea does sensitize us not only to Joyce’s ecological concerns but also to his anxieties about extinction, which we can find even in that oft-cited statement: “I want...to give a picture of Dublin so complete that if the city one day suddenly disappeared from the earth it could be reconstructed out of my book [

Ulysses]” (

Budgen 1972, p. 69). Yet, if Dublin were reconstructed literally or mechanically from the text of

Ulysses, the city would never be as lively as expected, but would be quite boring owing to many omissions and deficiencies. Responsible in that rich and colorful reconstruction will be the readers themselves, those who will be capable of seeing “behind it all”—noticing what remains inconspicuous or buried under the surface of the literary text—and those who will see something new and still unknown.