Growing Economic Inequality and Its (Partially) Political Roots

Abstract

:- ❖

- In 2013, America’s 25 highest-paid hedge fund managers made more than twice as much as all the kindergarten teachers in the country taken together (Krugman 2014).

- ❖

- In 2013, the combined family wealth of just six members of the Walton family added up to more than the wealth of 52.5 million, or 42.9 percent, of American families1.

- ❖

- The minimum wage was $2.65 per hour in 1978. Had it kept up with the cost of living, it would have been $9.62—not $7.25—in 2014. If it had kept up with the increase in compensation of CEOs of large corporations, it would have been $95.97 in 20142.

- ❖

- As measured by the poverty gap—that is, the percentage by which the mean income of the poor falls below the poverty line—the poor in the United States are quite poor indeed. In a group of 34 rich countries, only in Korea, Mexico, and Spain is the poverty gap higher3.

- ❖

- In state university systems, merit aid flows disproportionately to those who are less needy: about 1 in 5 students from households with incomes over $250,000 receive merit aid—in contrast to 1 in 10 from families making less than $30,000 (Rampell 2013).

1. Increasing Economic Inequality

1.1. Earnings

- ❖

- In the nation’s largest firms, CEO compensation rose 941 percent between 1978 and 2015, a rate far higher than the increase in the stock market (543 percent) or the pay of the top 0.1 percent of earners (320 percent).

- ❖

- Between 1973 and 2015, productivity increased 73 percent in the United States—at the same time that the average hourly earnings of nonsupervisory workers went up a mere 11 percent.

1.2. Wealth

2. The United States in Comparative Perspective

3. Does American Affluence Compensate?

4. What about the American Dream?

- Grow up with two biological parents;

- Live in a home environment that cultivates attitudes, interests, habits, and personality traits that are helpful in school and the marketplace;

- Benefit from parental investments in their development ranging from stimulating conversations to music lessons to summer camp;

- Attend schools with experienced teachers, educationally engaged fellow students, AP courses, and organized sports;

- Achieve academically in school;

- Be able to afford rising college tuitions and to have advisors at home and school able to guide them through the process of applying to college and finding financial aid, if needed;

- Matriculate in college and, ultimately, graduate;Be located in social networks that provide mentors and contacts along the way18.

| The class-based gap in parental expenditures on their children’s development—in such things as books, high-quality child care, summer camp, and private school—has grown. In the 1972–1973 period, families in the highest income group spent $2701 more per year on child enrichment than did families in the lowest income group. By the 2005–2006 period, the disparity had grown to $7,557. |

| Source: (Duncan and Murnane 2011b, p. 11). Data for lowest and highest income quintiles in 2008 dollars. |

5. How Do We Explain Increasing Economic Inequality?

5.1. Benefits and Taxes

5.2. Government Policy and the Shaping of Market Outcomes

5.3. Declining Unions and Growing Economic Inequality

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atkinson, Anthony. 2015. Inequality: What Can Be Done? Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Dean, and Jared Bernstein. 2013. Getting Back to Full Employment. Washington: Center for Economic and Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, Larry M. 2016. Unequal Democracy, 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bebchuk, Lucian, and Jesse Fried. 2004. Pay without Performance: The Unfulfilled Promise of Executive Compensation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bitler, Marianne, and Hilary Hoynes. 2016. The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same? The Safety Net and Poverty in the Great Recession. Journal of Labor Economics 34: S403–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivens, Josh. 2014. Walton Family Net Worth is a Case Study Why Growing Wealth Concentration Isn’t Just an Academic Worry. Economic Policy Institute Working Economics Blog. October 3. Available online: http://www.epi.org/blog/walton-family-net-worth-case-study-growing/ (accessed on 18 December 2015).

- Blau, Peter M., and Otis Dudley Duncan. 1967. The American Occupational Structure. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, Samuel, Herbert Gintis, and Melissa Osborne Groves, eds. 2005. Unequal Chances: Family Background and Economic Success. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, Mark D. 2007. Split: Class and Cultural Divides in American Politics. Washington: CQ Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges, Benjamin, and Robert V. Gesumaria. 2015. The Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) and Children: How and Why the SPM and Official Poverty Estimates Differ. Social Security Bulletin 75: 55–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2015. CPI Inflation Calculator. Available online: http://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm (accessed on 26 December 2015).

- Burtless, Gary, and Christopher Jencks. 2003. American Inequality and Its Consequences. In Agenda for the Nation. Edited by Henry J. Aaron, James M Lindsay and Pietro S. Nivola. Washington: Brookings Institution. [Google Scholar]

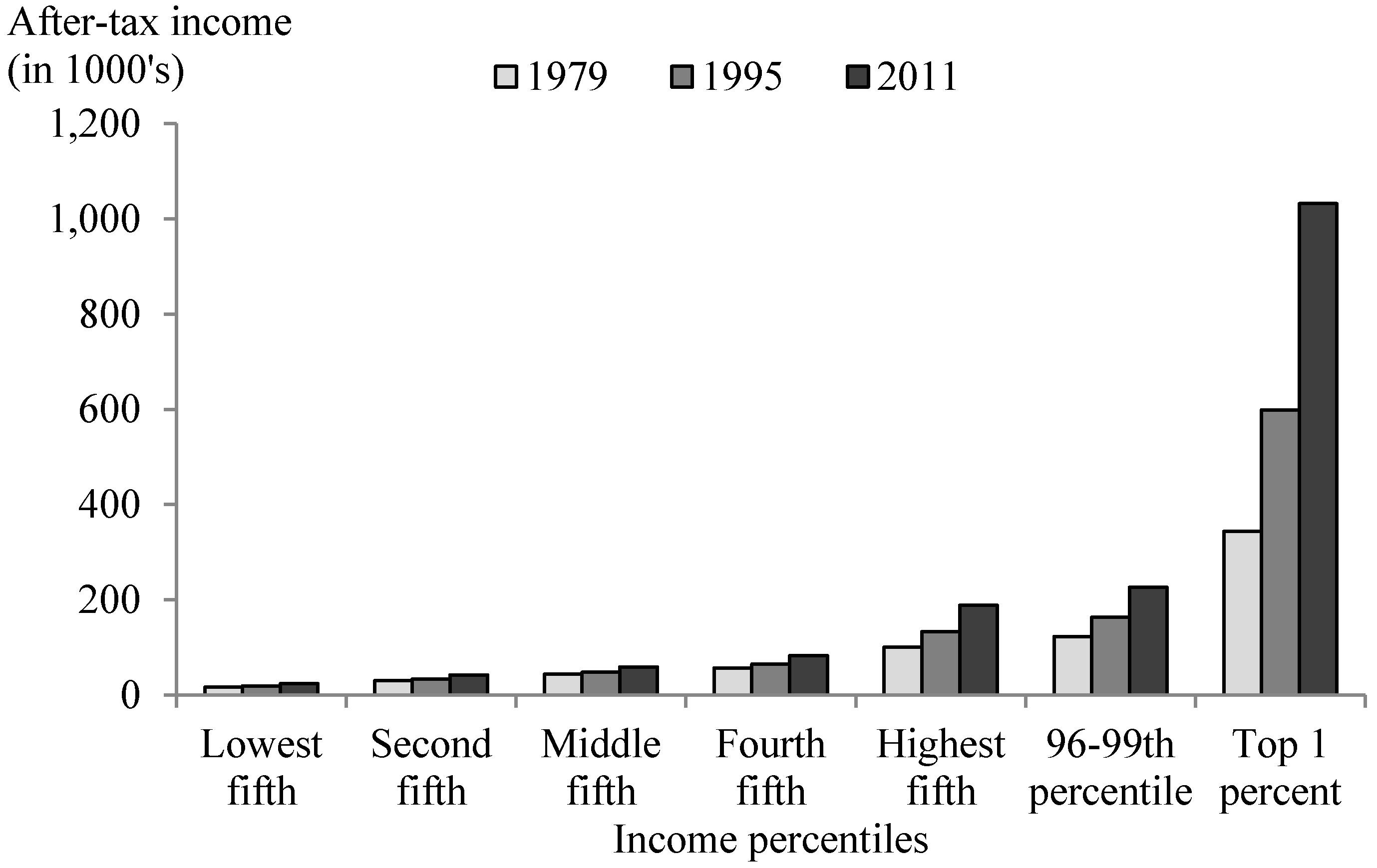

- Congressional Budget Office. 2011. Trends in the Distribution of Household Income between 1979 and 2007. October 25, Xii. Available online: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/42729 (accessed on 2 January 2016).

- Congressional Budget Office. 2014. The Distribution of Household Income and Federal Taxes, 2011. November 12. Available online: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/49440 (accessed on 2 January 2016).

- Corak, Miles. 2013. Income Equality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility. Journal of Economic Perspectives 27: 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Economic Advisers Brief. 2016. Labor Market Monopsony: Trends, Consequences, and Policy Responses. October. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/page/files/20161025_monopsony_labor_mrkt_cea.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2017).

- Dadush, Uri, Kemal Dervis, Sarah Puritz Milsom, and Bennett Stancil. 2012. Inequality in America: Facts, Trends, and International Perspectives. Washington: Brookings. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Julie Hirschfield, and Patricia Cohen. 2017. Trumps Plan Shifts Trillions to Wealthiest. New York Times, April 28. [Google Scholar]

- Drutman, Lee. 2015. The Business of America Is Lobbying. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, Greg J., and Richard J. Murnane, eds. 2011a. Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances. New York: Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, Greg J., and Richard J. Murnane. 2011b. Introduction: The American Dream, Then and Now. In Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances. Edited by Greg J. Duncan and Richard J. Murnane. New York: Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Economic Policy Institute. 2015. CEO Pay Has Grown 90 Times Faster than Typical Worker Pay Since 1978. July 1. Available online: http://www.epi.org/publication/ceo-pay-has-grown-90-times-faster-than-typical-worker-pay-since-1978/ (accessed on 26 December 2015).

- Economic Policy Institute. 2016. The Productivity–Pay Gap. August. Available online: http://www.epi.org/productivity-pay-gap/ (accessed on 14 January 2017).

- Edin, Kathryn J., and H. Luke Shaefer. 2015. $2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Elwell, Craig K. 2014. Inflation and the Real Minimum Wage: A Fact Sheet. Congressional Research Service. Available online: https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42973.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2016).

- Employment Benefit Research Institute. 2015. EBRI Databook on Employee Benefits. Available online: https://www.ebri.org/pdf/publications/books/databook/DB.Chapter%2005.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2016).

- Fieldhouse, Andrew. 2013. Rising Income Inequality and the Role of Shifting Market-Income Distribution, Tax Burdens, and Tax Rates. Economic Policy Institute, June 14. Available online: http://www.epi.org/publication/rising-income-inequality-role-shifting-market/ (accessed on 2 January 2016).

- Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. 2011. The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report. In U.S. Government Printing Office. Available online: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPO-FCIC/pdf/GPO-FCIC.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2016).

- Flanagan, Robert J. 2005. Has Management Strangled U.S. Unions? Journal of Labor Research 26: 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formisano, Ronald P. 2015. Plutocracy in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, Richard B. 1997. When Earnings Diverge: Causes, Consequences, and Cures for the New Inequality in the United States. Washington: National Policy Association, p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, Richard B. 2007. America Works: The Exceptional U.S. Market. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, Richard B., and Lawrence Katz. 1994. Rising Wage Inequality: The United States vs. Other Advanced Countries. In Working under Different Rules. Edited by Richard B. Freeman. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Ganzeboom, Harry B. G., Donald J. Treiman, and Wout C. Ultee. 1991. Comparative Intergenerational Stratification Research: Three Generations and Beyond. Annual Review of Sociology 17: 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfield, Michael. 1987. The Decline of Organized Labor in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gornick, Janet C., and Branko Milanovic. 2015. Income Inequality in the United States in Cross-National Perspective: Redistribution Revisited. LIS Center Research Brief. May 4. Available online: https://www.gc.cuny.edu/CUNY_GC/media/CUNY-Graduate-Center/PDF/Centers/LIS/LIS-Center-Research-Brief-1-2015.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2017).

- Gross, James A. 1995. Broken Promise: The Subversion of U.S. Labor Relations Policy, 1947–1994. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, Jacob S. 2006. The Great Risk Shift: The Assault on American Jobs, Families, Health Care, and Retirement and How You Can Fight Back. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, Jacob S., and Paul Pierson. 2010. Winner-Take-All Politics. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, Robert M., and David L. Featherman. 1977. The Process of Stratification. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, Barry, and David Macpherson. 2015. Union Membership and Coverage Database from the CPS. Available online: http://www.unionstats.com/ (accessed on 31 December 2015).

- Hout, Michael. 1988. More Universalism, Less Structural Mobility. American Journal of Sociology 93: 1358–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Chye-Ching, and Brandon DeBot. 2015. Ten Facts You Should Know About the Federal Estate Tax. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 23. Available online: http://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/1-8-15tax.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2016).

- Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. 2015. Who Pays?: A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All Fifty States, 5th ed. January. Available online: http://www.itep.org/whopays/full_report.php (accessed on 2 January 2016).

- Isaacs, Julia B., Isabel V. Sawhill, and Ron Haskins, eds. 2008. Getting Ahead or Losing Ground: Economic Mobility in America. Washington: Brookings Institution and Economic Mobility Project. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, Darien B., Brian G. Raub, and Barry W. Johnson. 2007. The Estate Tax: Ninety Years and Counting. Internal Revenue Service. In Compendium of Federal Transfer Tax and Personal Wealth Studies. Available online: https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/11pwcompench1aestate.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2017).

- Jencks, Christopher. 2005. Why Do So Many Jobs Pay So Badly? In Inequality Matters. Edited by James Lardner and David A. Smith. New York: New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, David Cay. 2007. The Great Tax Shift. In Inequality Matters. Edited by Lardner and Smith. New York: The New Press, pp. 168–73. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Michael B. 2001. The Price of Citizenship: Redefining the American Welfare State. New York: Henry Holt. [Google Scholar]

- Kens, Paul. 1998. Lochner v. New York: Economic Regulation on Trial. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, Alan. 2012. The Rise and Consequences of Inequality. Presentation Made to the Center for American Progress. January 12. Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/events/2012/01/12/17181/the-rise-and-consequences-of-inequality/ (accessed on 30 December 2015).

- Krugman, Paul. 2014. Now That’s Rich. New York Times, May 9. [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt, David, and Kevin Quealy. 2014. U.S. Middle Class Is No Longer the World’s Richest. New York Times, April 23. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Paul Alan. 1985. The Unidimensional Perspective of the Reagan Labor Board. Rutgers Law Journal 16: 269–390. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, Nelson. 2002. State of the Union. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, Ron. 2010. Student Debt and a Push for Fairness. New York Times, June 5. [Google Scholar]

- Mishel, Lawrence. 2012. Unions, Inequality, and Faltering Middle-Class Wages. Economic Policy Institute. August 29. Available online: http://www.epi.org/publication/ib342-unions-inequality-faltering-middle-class/ (accessed on 4 January 2016).

- Mishel, Lawrence, and Jessica Schieder. 2016. Economic Policy Institute. CEO Compensation Grew Faster Than The Wages of the Top 0.1 Percent and the Stock Market. July 13. Available online: http://www.epi.org/publication/ceo-compensation-grew-faster-than-the-wages-of-the-top-0-1-percent-and-the-stock-market/ (accessed on 16 May 2017).

- Mishel, Lawrence, and Ross Eisenbrey. 2015. How to Raise Wages: Policies That Work and Policies That Don’t. Briefing Paper #391. Washington: Economic Policy Institute, March 16. [Google Scholar]

- Mishel, Lawrence, Jared Bernstein, and Heidi Shierholz. 2009. The State of Working America, 2008/2009. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, ILR Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mishel, Lawrence, Josh Bivens, Elise Gould, and Heidi Shierholz. 2012. The State of Working America, 12th ed. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mishel, Lawrence, John Schmitt, and Heidi Shierholz. 2014. Wage Inequality: A Story of Policy Choices. New Labor Forum 23: 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, Terry. 1987. Interests, Institutions, and Positive Theory: The Politics of the NLRB. Studies in American Political Development 2: 266–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenson, Gretchen. 2015. Comparing Paychecks with CEOs. New York Times, April 12. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2014. OECD Factbook 2014: Economic, Environmental and Social Statistics. Paris: OECD Publishing, pp. 66–67. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/factbook-2014-en (accessed on 18 December 2015).

- Opfer, Chris. 2017. Trump Freezes Overtime, Pay Regulations. Bloomberg BNA. January 24. Available online: https://www.bna.com/trump-freezes-overtime-n73014450151/ (accessed on 26 April 2017).

- Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Piketty, Thomas, and Emmanuel Saez. 2003. Income Inequality in the United States, 1913–1998. Quarterly Journal of Economics 118: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Robert D. 2015. Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Rampell, Catherine. 2013. Freebies for the Rich. New York Times Magazine, September 29, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, Robert B. 2012. Beyond Outrage. New York: Random House, Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, Robert B. 2015. The Political Roots of Widening Inequality. The American Prospect, April 28, 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, Dottie, and Brynne Keith-Jennings. 2016. SNAP Costs and Caseloads Declining. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 8. Available online: http://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-costs-and-caseloads-declining (accessed on 16 August 2016).

- Rosenfeld, Jake. 2014. What Unions No Longer Do. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saez, Emmanuel, and Gabriel Zucman. 2016. Wealth Inequality in the United States since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized Income Data. Quarterly Journal of Economics 131: 519–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger-Katz, Margot. 2016. Bucking a Health Trend, Fewer Kids Are Dying. New York Times, June 19. [Google Scholar]

- Schlozman, Kay Lehman, Sidney Verba, and Henry E. Brady. 2012. The Unheavenly Chorus: Unequal Political Voice and the Broken Promise of American Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Short, Kathleen. 2015. The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2014. In Current Population Reports; September. Available online: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p60-254.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2017).

- Smeeding, Timothy M. 2005. Public Policy, Economic Inequality, and Poverty: The United States in Comparative Perspective. Social Science Quarterly 86: 955–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. 2013. The Price of Inequality. New York: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. 2015. Rewriting the Rules of the American Economy. The Roosevelt Institute. Available online: http://rooseveltinstitute.org/rewriting-rules-report/ (accessed on 14 January 2017).

- Stonecash, Jeffrey M. 2010. Class in American Politics. In New Directions in American Politics. Edited by Jeffrey M. Stonecash. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wage and Hour Division. 2015. History of Federal Minimum Wage Rates under the Fair Labor Standards Act. Available online: https://www.dol.gov/whd/minwage/chart.htm (accessed on 16 May 2017).

- Warren, Elizabeth, and Amelia Warren Tyagi. 2003. The Two-Income Trap. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Western, Bruce, and Jake Rosenfeld. 2011. Unions, Norms, and the Rise in U.S. Wage Inequality. American Sociological Review 76: 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziliak, James P. 2015. Income, Program Participation, and Financial Vulnerability: Research and Data Needs. Journal of Economic and Social Measurement 40: 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Walton Family Net Worth is a Case Study Why Growing Wealth Concentration Isn’t Just an Academic Worry. Economic Policy Institute Working Economics Blog, posted October 3 (Bivens 2014). |

| 2 | The minimum wage for 1978 is found at U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division. 1938–2009. (Wage and Hour Division 2015); cost of living adjustment is taken from U. S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2015), CPI Inflation Calculator; the rate of growth of CEO pay (including the value of stock options exercised in a given year plus salary, bonuses, restricted stock grants, and long-term incentive payouts) for chief executives of the top 350 U.S. firms is taken from Lawrence Mishel and Alyssa Davis. (Economic Policy Institute 2015). |

| 3 | Data are for the 34 members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The poverty rate is the proportion of the population whose incomes are below half the median for the population as a whole. (OECD 2014, pp. 66–67) |

| 4 | |

| 5 | For extensive additional bibliography and discussion of technical matters, see (Schlozman et al. 2012, chp. 3). See, also, (Piketty and Saez 2003, pp. 1–39; Burtless and Jencks 2003, chp. 3; Mishel et al. 2012; Piketty 2014, esp. Part III; Atkinson 2015, chp. 1). |

| 6 | There is controversy among economists about the long-used official definition of poverty. An alternative measure, which takes account of in-kind government benefits, shows lower rates of poverty among children and higher rates among adults, especially the elderly. See (Bridges and Gesumaria 2015, pp. 55–81; Short 2015, pp. 60–254). |

| 7 | (Stiglitz 2013, p. 20). On desperate poverty, see (Edin and Shaefer 2015). |

| 8 | (Economic Policy Institute 2015). The figure is for chief executives of the top 350 U.S. firms and includes the value of stock options exercised in a given year plus salary, bonuses, restricted stock grants, and long-term incentive payouts. |

| 9 | See (Bebchuk and Fried 2004) |

| 10 | Cited in (Reich 2012, p. 11) |

| 11 | Cited in (Stiglitz 2013, p. 257). |

| 12 | On the erosion of the private welfare state, see (Katz 2001, chps. 6–8; Hacker 2006). |

| 13 | Figure taken from Employment Benefit Research Institute (2015, Table 5.1a), EBRI Databook on Employee Benefits. |

| 14 | Discussion in this paragraph is taken from (Mishel et al. 2012, pp. 376, 385–95). |

| 15 | This section draws on arguments and data in (Burtless and Jencks 2003; Smeeding 2005; Piketty 2014, especially chps. 8–9; Atkinson 2015, chp. 2). Making cross-national comparisons with regard to these issues poses technical dilemmas. See these sources as well the discussions and citations in (Schlozman et al. 2012, pp. 76–79). |

| 16 | |

| 17 | In a vast literature, see, for example, (Blau and Duncan 1967; Hauser and Featherman 1977; Hout 1988, pp. 1358–400; Ganzeboom et al. 1991, p. 284; Burtless and Jencks 2003); the essays in (Bowles et al. 2005); and the essays in (Isaacs et al. 2008). |

| 18 | On the class gaps in child well-being, see (Putnam 2015). With respect to the educational system, see the essays and references in (Duncan and Murnane 2011a), in particular, (Duncan and Murnane, “Introduction,” chp. 1; Reardon, Sean F. “The Widening Academic Achievement Gap between the Rich and the Poor: New Evidence and Possible Explanations,” chap. 5; and Bailey, Martha J., and Susan M. Dynarski, “Inequality in Postsecondary Education,” chp. 6.) |

| 19 | An exception to the pattern of growing gaps between rich and poor children is diminution in the disparity in health between rich and poor for children and young adults. See (Sanger-Katz 2016) |

| 20 | (Corak 2013, Figure 1). See also, (Krueger 2012). |

| 21 | Discussion of such factors is contained in (Dadush et al. 2012, chp. 4). See also, (Atkinson 2015, chp. 3). |

| 22 | Testimony before the Massachusetts legislature, cited without additional bibliographic information in (Kens 1998, p. 19). On the extent to which executive pay reflects forces other than the operations of markets, see (Bebchuk and Fried 2004, Parts I and II). |

| 23 | For evidence and citations supporting the contention that government benefits reduce poverty, see (Ziliak 2015, pp. 34–36). |

| 24 | (Congressional Budget Office 2014, pp. 25–27). A parallel CBO analysis undertaken three years earlier found the opposite, a decrease in the redistributive impact of government benefits, for the period between 1979 and 2007. See (Congressional Budget Office 2011, Xii). |

| 25 | Material in the paragraph is taken from (Johnston 2007, pp. 168–73). |

| 26 | (Congressional Budget Office 2014, Figure 15). See also, (Fieldhouse 2013). |

| 27 | Information in this paragraph is taken from (Stiglitz 2013, pp. 89–92); and (Formisano 2015, pp. 77–80). |

| 28 | For information about the estate tax, see (Jacobson et al. 2007, volume 2, chp. 1); (Jacobson et al. 2007) and (Huang and DeBot 2015). |

| 29 | (Atkinson 2015, pp. 181–82). See also, (Piketty 2014, pp. 499, 508). |

| 30 | Among others, this argument is made by Piketty (2014, pp. 508–12), who finds no evidence that the explosion in compensation has been accompanied by enhanced productivity by high earners. |

| 31 | (Mishel and Eisenbrey 2015, p. 10). In the final year of the Obama administration, the Department of Labor put out a rule making many additional workers eligible for overtime pay. Immediately after Trump took office, this rule was suspended. See (Opfer 2017). |

| 32 | These and other practices are discussed in (Stiglitz 2015) and (Council of Economic Advisers Brief 2016). The specific examples of lower-wage workers who are required to sign non-competes are in (Council of Economic Advisers Brief 2016, p. 8). |

| 33 | For conflicting views on the causes of the 2008 financial crisis, see (Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission 2011), including the two dissenting reports. Material in the remainder of this section is taken from (Warren and Tyagi 2003, pp. 126–29, 152–56; Stiglitz 2013, pp. 46, 93, 112–15, 239–45, 252, 310; Reich 2012, pp. 57–58). |

| 34 | One provision in the 2005 bankruptcy act made it extremely difficult to discharge private student loans—in contrast to, for example, consumer debt—through bankruptcy. See (Lieber 2010). |

| 35 | Data taken from the Union Membership and Coverage Database constructed by Barry Hirsch and David Macpherson. (Hirsch and Macpherson 2015) |

| 36 | (Flanagan 2005, p. 35. Table 1). See (Mishel et al. 2009, p. 375). Of the thirteen countries about which they present data, union coverage is lowest in the United States. |

| 37 | See (Mishel 2012; Rosenfeld 2014, chps. 2–3). |

| 38 | For a more extensive discussion and additional bibliographical sources, see (Schlozman et al. 2012, pp. 87–94); as well as (Freeman 2007, chp. 5). See also (Goldfield 1987; Freeman and Katz 1994; Hacker and Pierson 2010, pp. 56–61; Rosenfeld 2014, chp. 1). |

| 39 | On these factors, see (Lichtenstein 2002, chps. 3–4). |

| 40 | |

| 41 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schlozman, K.L.; Brady, H.E.; Verba, S. Growing Economic Inequality and Its (Partially) Political Roots. Religions 2017, 8, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8050097

Schlozman KL, Brady HE, Verba S. Growing Economic Inequality and Its (Partially) Political Roots. Religions. 2017; 8(5):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8050097

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchlozman, Kay Lehman, Henry E. Brady, and Sidney Verba. 2017. "Growing Economic Inequality and Its (Partially) Political Roots" Religions 8, no. 5: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8050097