Studying Organizations on Instagram

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Online Visual Communication: An Emerging Field

“[A]n expanding subfield of communication science that uses social scientific methods to explain the production, distribution and reception processes, but also the meanings of mass-mediated visuals in contemporary social, cultural, economic and political contexts. Following an empirical, social scientific tradition that is based on a multidisciplinary background, visual communication research is problem-oriented, critical in its method, and pedagogical intentions, and aimed at understanding and explaining current visual phenomena and their implications for the immediate future.”

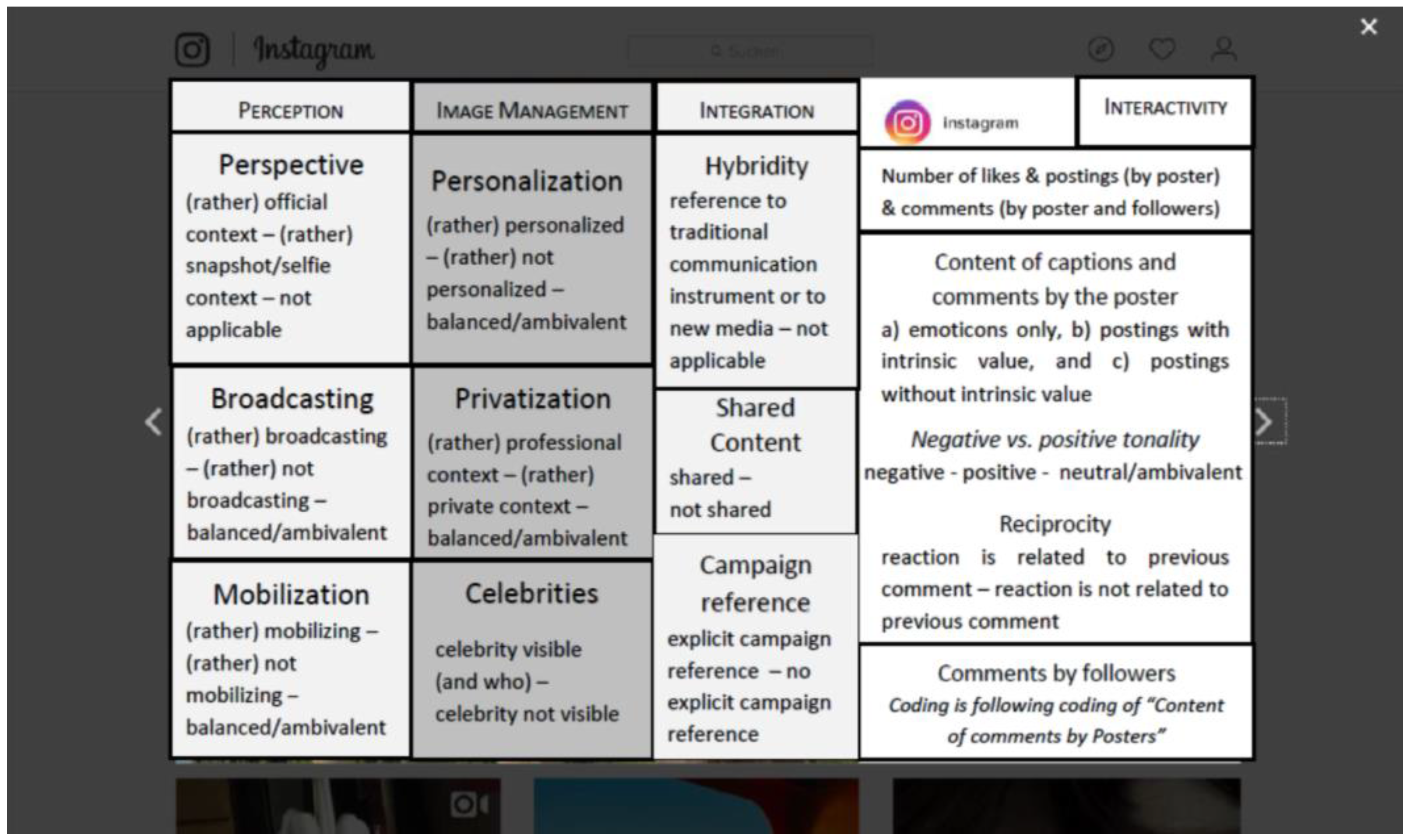

2. Methodological Framework: How to Analyze Instagram?

2.1. Perception

2.2. Image Management

2.3. Integration

2.4. Interactivity

2.4.1. Content of Captions and of Comments

2.4.2. Negative vs. Positive Tonality

2.4.3. Reciprocity

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Internet World Stats. Available online: http://www.internetworldstats.com (accessed on 19 June 2016).

- Barnes, N.G.; Lescault, A.M.; Andonian, J. Social Media Surge by the 2012 Fortune 500: Increase Use of Blogs, Facebook, Twitter and More. Available online: http://www.umassd.edu/cmr/socialmedia/2012fortune500/ (accessed on 19 June 2014).

- Rußmann, U. Die Ö Top 500 im Web: Der Einsatz von Social Media in österreichischen Großunternehmen. Eine Bestandsaufnahme. Medien J. 2015, 39, 19–34. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Government Accountability Office. Federal agencies need policies and procedures for managing and protecting information they access and disseminate. Available online: http://www.gao.gov/assets/330/320251.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2016).

- Lovejoy, K.; Waters, R.D.; Saxton, G.D. Engaging stakeholders through Twitter: How nonprofit organizations are getting more out of 140 characters or less. Public Relat. Rev. 2012, 38, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, R.; Burnett, E.; Lamm, A.; Lucas, J. Engaging stakeholders through social networking: How nonprofit organizations are using Facebook. Public Relat. Rev. 2009, 35, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enli, G.; Moe, H. Social media and election campaigns—Key tendencies and ways forward. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2013, 16, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PEW Research Center. Available online: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/08/19/the-demographics-of-social-media-users/ (accessed on 4 July 2016).

- Findahl, O. Svenskarna och Internet. En årlig studie av svenska folkets internetvanor (The Swedes and the internet 2014: An annual study of the Swedish people’s internet habits). Available online: http://www.soi2014.se/ (accessed on 19 June 2016). (In Swedish)

- Facebook Business: Capture Attention with Updated Features for Video Ads. Available online: http://www.facebook.com/business/news/updated-features-for-video-ads (accessed on 15 March 2016).

- Kupferschmitt, T. Bewegtbildnutzung nimmt weiter zu—Habitualisierung bei 14- bis 29-Jährigen. Media Perspekt. 2015, 9, 383–391. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Fiegerman, S. Instagram tops 300 million active users, likely bigger than Twitter. Available online: http://mashable.com/2014/12/10/instagram-300-million-users/ (accessed on 19 June 2016).

- Instagram. Press news. Available online: http//:www.instagram.com/press/ (accessed on 19 June 2016).

- Schill, D. The Visual Image and the Political Image: A Review of Visual Communication Research in the Field of Political Communication. Rev. Commun. 2012, 12, 118–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Lee, J.-A.; Moon, J.H.; Sung, Y. Pictures Speak Louder than Words: Motivations for Using Instagram. Cyberpsychol. Behave. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.; Sanderson, J. I’m Going to Instagram It! An Analysis of Athlete Self-Presentation on Instagram. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2015, 59, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.; Ganz, O.; Vallone, D. The cigar ambassador: How Snoop Dogg uses Instagram to promote tobacco use. Tob Control 2014, 23, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russmann, U.; Svensson, J. Interaction on Instagram? Glimpses from the Swedish 2014 Elections. In Proceedings of the IPSA Communication, Democracy and Digital Technology Conference, Rovinj, Croatia, 1–3 October 2015.

- Filimonov, K.; Russmann, U.; Svensson, J. Picturing the Party. Instagram and Party Campaigning in the 2014 Swedish Elections. Soc. Media Soci. 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobinger, K. Visuelle Kommunikation. In Kommunikationswissschaft als Integrationsdisziplin; Karmasin, M., Rath, M., Thomaß, B., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014; pp. 299–316. [Google Scholar]

- Barnhurst, K.; Vari, M.; Rodrigues, I. Mapping Visual Studies in Communication. J. Commun. 2004, 54, 616–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.G. What is visual communication? Past and future of an emerging field of communication research. Stud. Commun. Sci. 2007, 7, 7–34. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, M.G.; Kappas, A.; Olk, B. Perceiving press photography: A new integrative model, combining iconology with psychophysiological and eye-tracking. Vis. Commun. 2012, 11, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, G. Was ist ein Bild? Fink: Munich, Germany, 1994. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, R. Rhetoric of the Image. In Image—Music—Text; Heath, S., Ed.; Hill and Wang: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 32–51. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, A. The possibility and actuality of visual arguments. Argum. Advocacy 1996, 3, 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Brantner, C.; Katharina Lobinger, K.; Wetzstein, I. Effects of visual framing on emotional responses and evaluations of news stories about the Gaza conflict 2009. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2011, 88, 523–540. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher, H.-J.; Schumacher, P. The relevance of attention for selecting news content. An eye-tracking study on attention patterns in the reception of print and online media. Commun. Eur. J. Commun. Res. 2006, 3, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, S.; Bock, M.A.; Wanta, W. Visual Communication Theory and Research. A Mass Communication Perspective; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McQuarrie, E.F.; Phillips, B. It’s not your father’s magazine ad: Magnitude and direction of recent changes in advertising style. J. Advert. 2008, 37, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au-Yong-Oliveira, M.; Ferreira, J.J. What If Colorful Images Become more Important than Words? Visual Representations as the Basic Building Blocks of Human Communication and Dynamic Storytelling. World Future Rev. 2014, 6, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, J. Negotiating the Political Self on Social Media Platforms. An In-Depth Study of Image-Management in an Election-Campaign in a Multi-Party Democracy. JeDEM eJ. eDemocr. 2012, 4, 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Russmann, U. Online Political Discourse on Facebook: An Analysis of Political Campaign Communication in Austria. J. Political Consult. Policy Adv. 2012, 3, 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Golbeck, J.; Grimes, J.M.; Rogers, A. Twitter Use by the US Congress. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2010, 61, 1612–1621. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, T.; Broersma, M.; Hazelhoff, K.; van ´t Haar, G. Between broadcasting political messages and interacting with voters. The use of Twitter during the 2010 UK general election. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2013, 16, 692–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foot, K.A.; Schneider, S.M. Web Campaigning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, N.; Lilleker, D. Microblogging, Constituency Service and Impression Management: UK MPs and the Use of Twitter. J. Legis. Stud. 2011, 17, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.B.; Gulati, G.J. Social networks in political campaigns: Facebook and the congressional elections of 2006 and 2008. New Media Soc. 2012, 15, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccari, C. From echo chamber to persuasive device? Rethinking the role of the Inter-net in campaigns. New Media Soc. 2013, 15, 109–127. [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy, K.; Saxton, G.D. Information, Community, and Action: How Nonprofit Organizations Use Social Media. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2012, 17, 337–353. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns, A. Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and Beyond: From Production to Produsage; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Garrigos-Simon, F.J.; Alcamí, R.L.; Ribera, T.B. Social networks and Web 3.0: Their impact on the management and marketing of organizations. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 1880–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanyer, J. Elected Representatives, Online Self-preservation and the Personal Vote: Party, Personality and Webstyles in the United States and the United Kingdom. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2008, 11, 414–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life; Anchor Books: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Vergeer, M.; Hermans, L.; Sams, S. Is the voter only a tweet away? Microblogging during the 2009 European Parliament election campaign in the Netherlands. Available online: http://firstmonday.org/article/view/3540/3026 (accessed on 25 June 2016).

- Bauman, Z. The Individualized Society; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Papachariss, Z. A Private Sphere: Democracy in a Digital Age; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fill, C. Marketing Communications. In Engagement, Strategies and Practice, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: Essex, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McAllister, I. The personalization of politics. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior; Russel, J., Dalton, R.J., KLlingemann, H.-D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 571–588. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans, L.; Vergeer, M. Personalization in e-campaigning: A cross-national comparison of personalization strategies used on candidate websites of 17 countries in EP elections 2009. New Media Soc. 2013, 15, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plasser, F. Political Consulting Worldwide. In The Routledge Handbook of Political Management; Johnson, D.W., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 24–41. [Google Scholar]

- Macnamara, J.; Zerfass, A. Social Media Communication in Organizations: The Challenges of Balancing Openness, Strategy, and Management. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2012, 6, 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A. The Hybrid Media System. Politics and Power; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Postman, N. Teaching as a Conserving Activity; Delacorte Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, J. Nina on the Net—A study of a politician campaigning on social networking sites. Cent. Eur. J. Commun. 2011, 5, 190–206. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, J. Models of Democracy and Concepts of Communication. In Digital Democracy; Issues of Theory and Practice; Hacker, K., van Dijk, J., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Riggins, P. The Future of Stakeholder Engagement; Brunswick: Dallas, TX, USA, 2013; Available online: http://www.brunswickgroup.com/publications/reports/the-future-of-stakeholder-engagement/ (accessed on 19 June 2016).

- Lopez-Lopez, I.; Ruiz-de-Maya, S.; Warlop, L. When Sharing Consumption Emotions With Strangers Is More Satisfying Than Sharing Them With Friends. J. Serv. Res. 2014, 17, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kies, R. Promises and Limits of Web-Deliberation; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sweetser, K.D.; Weaver Lariscy, R. Candidates Make Good Friends: An Analysis of Candidates’ Uses of Facebook. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2008, 2, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PEW Research Center: Teens, Social Media & Technology Overview 2015. Available online: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/09/teens-social-media-technology-2015/ (accessed on 5 July 2016).

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Russmann, U.; Svensson, J. Studying Organizations on Instagram. Information 2016, 7, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/info7040058

Russmann U, Svensson J. Studying Organizations on Instagram. Information. 2016; 7(4):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/info7040058

Chicago/Turabian StyleRussmann, Uta, and Jakob Svensson. 2016. "Studying Organizations on Instagram" Information 7, no. 4: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/info7040058