1. Introduction

The optical klystron (OK) concept was proposed by Vinokurov and Skrinsky in 1977 [

1] to enhance the gain of an oscillator free electron laser (FEL) driven by a storage ring. The basic scheme consists of two undulators separated by a dispersive section, which converts the beam energy modulation produced in the first undulator into a density modulation, thus enhancing the electron bunching and the radiation emission in the second undulator. The first implementation of the OK FEL scheme was realized in 1979 at the VEPP-3 storage ring of the Budker Institute of Nuclear Physics (BINP, Novosibirsk, Russia) [

2], where they obtained an initial gain of 0.5% at 630 nm that was later improved up to 2.5% per pass [

3]. Afterwards, other FEL oscillator facilities implemented the OK scheme, such as ACO SR FEL (LURE, France), which lased at 635 nm in 1983 [

4] and at 463 nm in 1987 [

5]. The progress in optical cavity mirror coatings allowed later for lasing in ultra-violet, at 240 nm in 1989 (OK-4/VEPP-3 storage ring FEL [

6]) and below, down to 193 nm in 1999 (OK-4 Duke SR FEL [

7]). In 2000, the ELETTRA storage ring FEL lased at 217.9 nm [

8,

9] and a few years later at 190 nm, which is the shortest wavelength obtained with an OK FEL oscillator [

10]. The gain of the optical klystron decreases with decreasing wavelength, while the optical cavity mirrors’ losses increase, and this has constituted a strong constraint in reaching emission at shorter wavelengths. A distributed optical klystron was proposed by Litvinenko [

11] to increase the gain. The first successful experiment was conducted in the DOK-1 FEL, at Duke University, Durham, NC, USA [

12], obtaining a gain of about 48% per pass.

The progress of linac technologies has allowed for generating very high brightness electron beams able to drive single-pass high-gain FELs, providing intense radiation in the extreme-ultra-violet [

13,

14,

15] and in the X-ray regimes [

16,

17]. A common high-gain FEL mode of operation is the self-amplified spontaneous emission (SASE) mode, where a high brightness electron beam is driven through a long undulator tuned to emit radiation with a central wavelength

. The incoherent spontaneous radiation emitted by the beam interacts with the beam itself and is amplified. The FEL signal grows exponentially along the undulator with a characteristic power folding length

[

18,

19] where

is the undulator period and

ρ is the Pierce parameter, also known as the FEL parameter [

20,

21,

22], typically in the range

. The radiation intensity growth saturates after about

. The saturation length corresponds to the undulator distance required to extract the maximum energy from the electron beam. This distance can be of the order of 100 m for an FEL operating in the hard X-rays. Theoretical studies [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28] have shown that the increase in density modulation induced by the optical klystron dispersive section may significantly reduce the saturation length.

An Optical Klystron device, originally introduced to enhance the gain in oscillator FELs, can be used to shorten the undulator required to reach saturation in single-pass SASE FEL devices. This concept was successfully demonstrated on the FEL-1 line at the FERMI facility [

29]. We extend the OK using a multi-stage configuration in which several dispersive sections are inserted along the undulator. We have exploited this scheme in the FERMI FEL-2 layout, which includes three dispersive sections alternated to undulator segments. The values of the dispersions were optimized to maximize the SASE FEL emission in the soft X-rays. The paper is organized as follows. A review of the optical klystron concept in the context of enhancing the SASE performance is provided in

Section 2. The first experiment based on a single OK scheme and carried on at FERMI FEL-1 is addressed in

Section 3, where we show the performance of the OK in the vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) regime in comparison with the theoretical expectations and simulations. In

Section 4, the new experiment in the soft X-ray regime of multi-stage OK with the three dispersive sections of the FERMI FEL-2 line is described.

2. Theoretical Gain of the Optical Klystron SASE Relative to the SASE FEL

The aforementioned theoretical studies that were focused on the possibility of applying the optical klystron concept to high-gain FEL amplifiers have provided an important result: the OK high-gain FEL performance is strongly influenced by the electron beam relative uncorrelated energy spread, which has to be substantially lower than the

ρ FEL parameter. We briefly recall the one-dimensional theoretical approach developed in [

25,

28] that provides an approximate expression for the gain factor

G of the optical klystron relative to the SASE operating without enabling the dispersive section.

We consider the FEL resonant wavelength condition

, where

is the normalized undulator strength,

is the peak magnetic field and

is the electron energy. We assume a Gaussian distribution of the electron energies with an rms value

, where

is the relative energy deviation from the mean value. The OK enhancement factor to the radiation electric field

E at the scaled frequency

can be written as follows [

28]:

where

,

μ is the complex growth rate of the radiation field in each undulator,

is the normalized energy distribution of the electron bunch and

is the momentum compaction of the dispersive section. Integrating the enhancement factor

over the SASE spectrum

, which is assumed to be Gaussian with an rms bandwidth equal to

ρ, one can obtain the OK power gain factor

G as:

If the first undulator induces an energy modulation with an amplitude smaller than the intrinsic energy spread, the second term in the integral at the numerator dominates over the first one. In this case and considering (

), the gain factor

G can be well approximated by the following equation [

28] (the equation reported in [

28] contains a typo that has been fixed in Equation (

3)):

where

.

When the strength of the dispersive section is low, i.e.,

is of the order of few

, the chicane works as a phase shifter and the effect of the OK on FEL gain is mainly interferential. By further increasing the chicane strength, the microbunching induced by the OK dominates and the gain factor

G increases progressively up to the maximum FEL intensity that occurs when

. Since

, when the

is close to the optimum value, D is much larger than 1 so that Equation (

3) reduces to [

28]:

It is straightforward to see that

G is maximized when

and the maximum theoretical power gain factor

is:

Equation (

5) confirms that the smaller the uncorrelated energy spread of the beam, the higher the

is expected to be.

On the other hand, if the first undulator is sufficiently long to induce a deep energy modulation, comparable to or larger than the intrinsic energy spread, the maximum gain of the OK does not occur more for

. In order to better figure out what happens in this scenario, it is helpful to take into account the analytical treatment originally developed for the High Gain Harmonic Generation (HGHG) FEL [

30]. In the latter scheme, an external seed laser interacts with the electron bunch in an undulator, named the modulator, imprinting a periodic energy modulation at the seed laser wavelength

with an amplitude

. This energy modulation is converted into density modulation by means of a dispersive section, as in the optical klystron, and then the beam is sent to an undulator, named the radiator, tuned at

, or, more often, to a higher harmonic

. A figure of merit of the HGHG scheme is the so-called “bunching factor”, representing the normalised density modulation at the

nth harmonic and defined as:

where

is the

nth order of the Bessel function.

We can use Equation (

6) for describing the OK behavior versus

, taking

as the energy modulation induced by the radiation of the first undulator. For example, we have considered an electron bunch with a mean energy of 1.5 GeV and an intrinsic energy spread of 50 keV (

). The undulators are all tuned to be resonant at 5 nm, thus

.

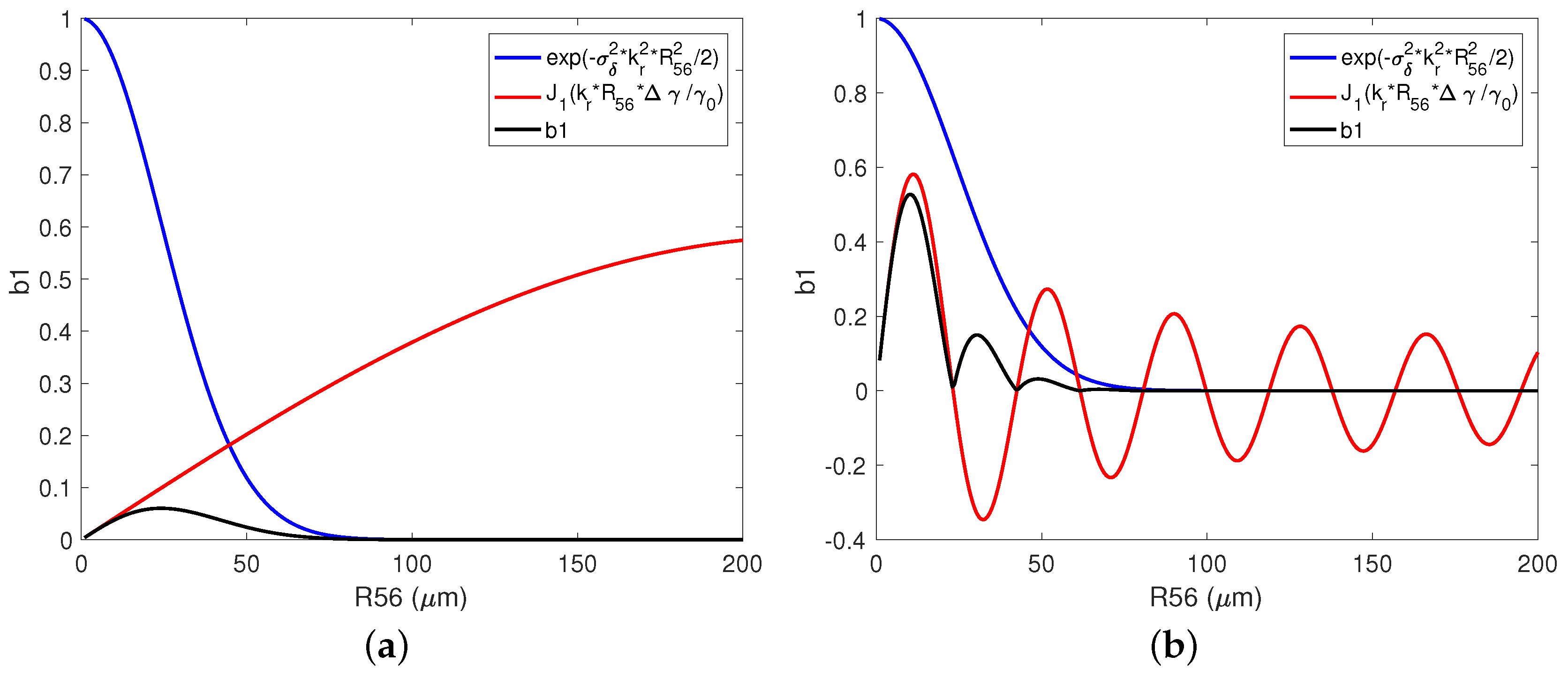

Figure 1 shows the bunching factor versus

when the first undulator induced an energy modulation of 10 keV and 200 keV. In the former scenario (see

Figure 1a), being

, the contribution to the bunching coming from the exponential decay dominates over the Bessel function and the maximum bunching occurs when

, thus in agreement with the results of Equation (

5). In the scenario plotted in

Figure 1b, the induced modulation is much larger than the intrinsic energy spread and the Bessel function dominates: the maximum bunching is obtained when the Bessel function assumes the peak value, which means when

[

31]. This is what happens in a seed FEL or eventually in a SASE after several gain length.

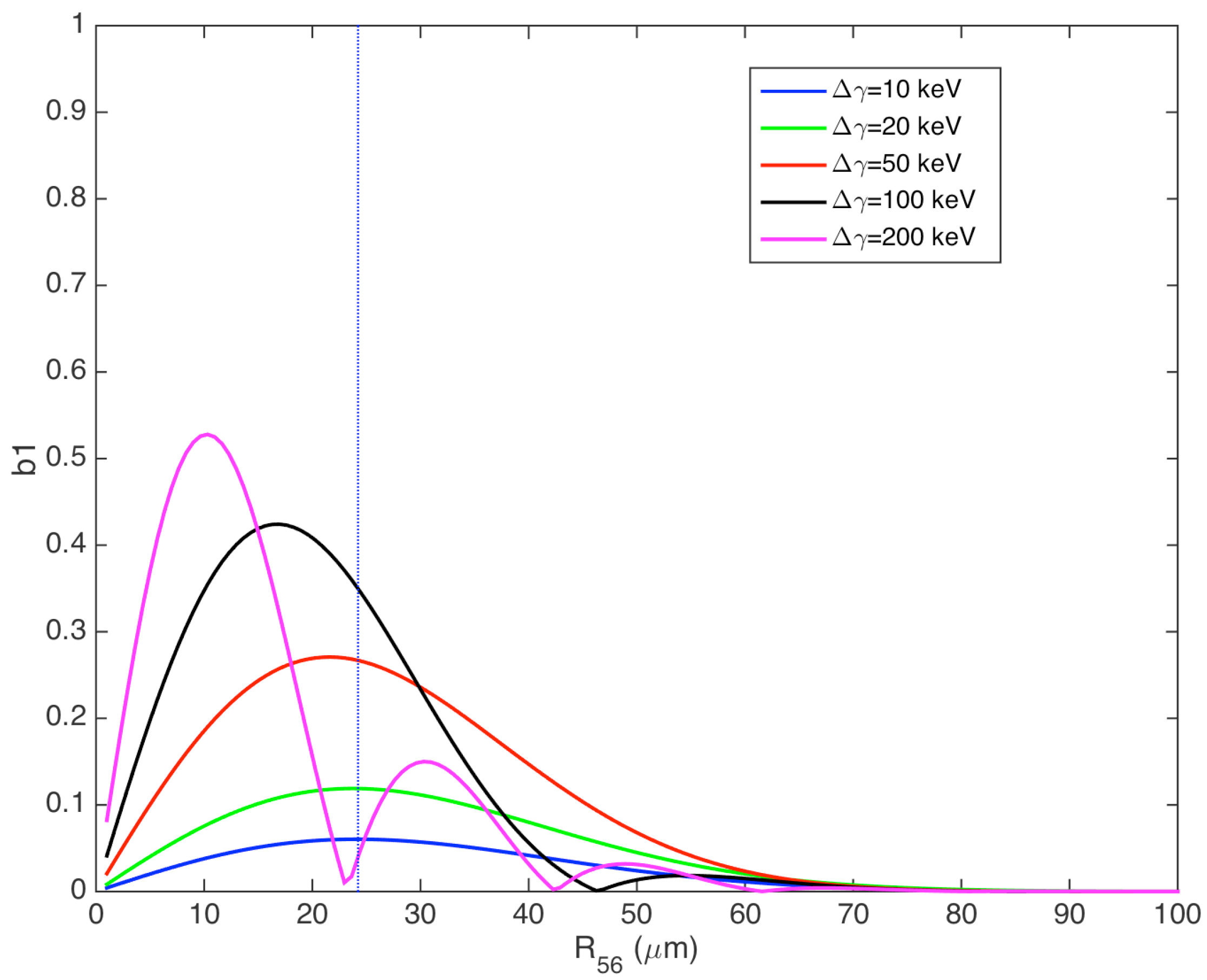

If the OK scheme is replicated in a second stage, the bunched electron beam passing through the second undulator could be able to generate an intense radiation inducing an energy modulation comparable with the intrinsic energy spread. If this happens, the optimum

of the second dispersive section maximizing the bunching of the second stage is shifted towards lower values, as shown in

Figure 2.

3. Experimental Demonstration of the OK SASE on the FEL-1 Line at FERMI

As mentioned in the introduction, the first experimental demonstration of the optical klystron enhancement to a SASE FEL was performed on the FEL-1 line at FERMI in the VUV spectral range. FEL-1 [

14] was designed to operate in HGHG mode, but it has been found to be suitable to realize an optical klystron in a high-gain FEL, by simply tuning both the modulator and the radiators at the same wavelength and exploiting the dispersive section to enhance the bunching induced by the spontaneous emission produced in the modulator. The wavelength tuning for both modulator and radiators is realized by changing the undulator gap [

32,

33]. The FERMI electron bunch has a strong requirement on the intrinsic energy spread

that derives from the HGHG FEL mode: in order to efficiently lase at the harmonic

n of the seed laser,

should be smaller than

. A laser heater system [

34,

35] has been installed after the injector [

36] at 100 MeV to suppress the microbunching instability driven by the coherent synchrotron radiation in the magnetic bunch compressor and by the longitudinal space charge forces along the linac. A fine-tuning of the laser heater energy per pulse, in the range 0.5–1.0

J, permits us to constrain

after the compression and the linac transport to less than

[

37]. Considering the typical spectral range of FEL-1 operation, this means

with a relevant improvement in the FEL output performance [

38]. Nevertheless, we have intentionally increased the beam intrinsic energy spread by exploiting the laser heater in order to study the OK performance as a function of

.

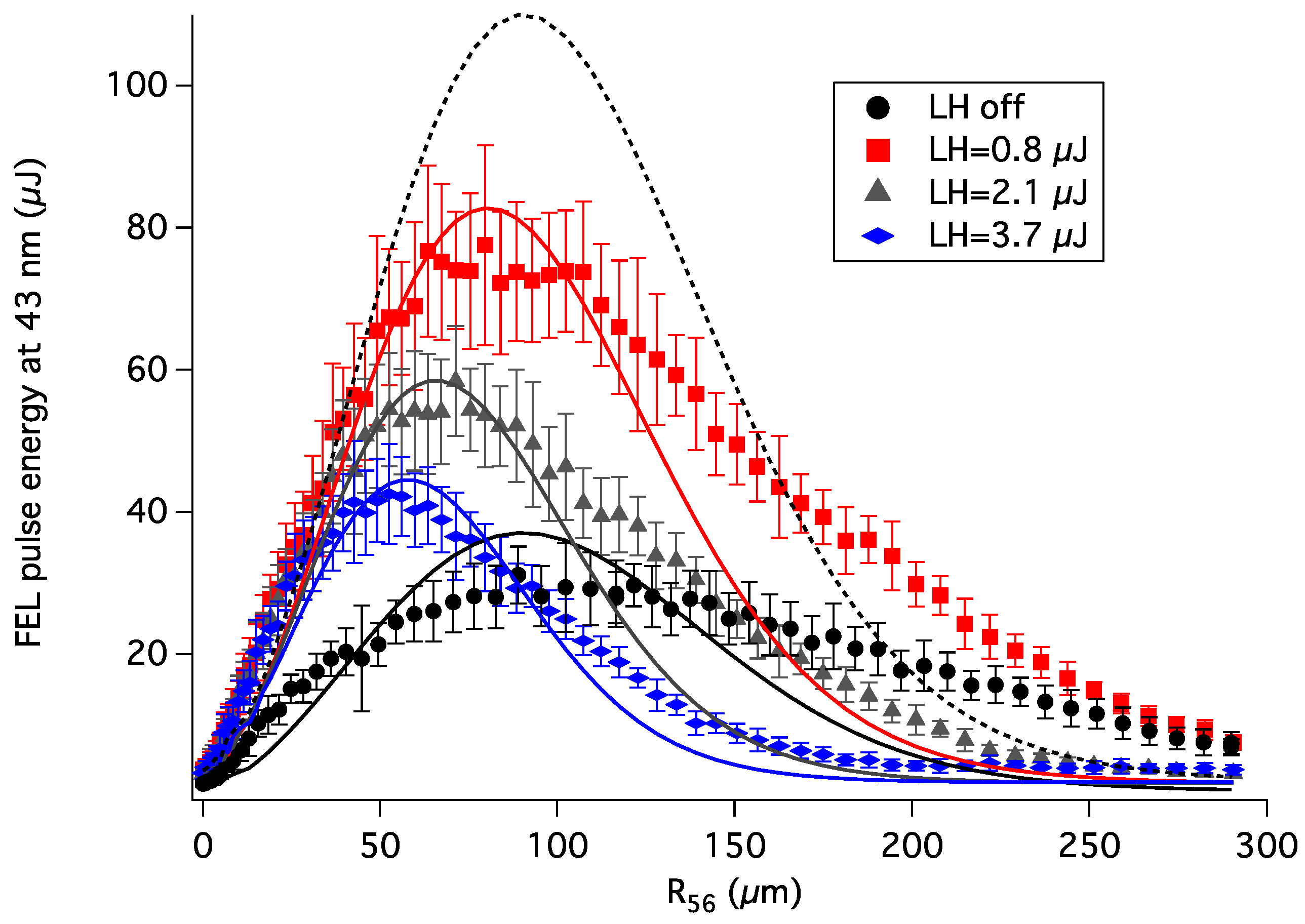

In the experiment reported in the paper [

29], a 1.058 GeV-500 A electron beam was used, with a normalized emittance (

) of about 1.2 mm mrad. Both modulator and radiators have been tuned at 43 nm. Without activating the dispersive section, i.e.,

m, the FEL energy per pulse was measured to be only a few micro-Joules (“pure” SASE mode). The optimization of the laser heater intensity (

J) led to minimizing the uncorrelated energy spread at the end of the linac, which we measured to be about 90 keV (rms). This is also the best condition for the OK. Then, the dispersive section

has been progressively increased in the range 0 to 300

m, while detecting the output FEL intensity by means of calibrated gas cells [

39]. We call

the experimental value of

that maximizes the OK FEL pulse energy, and, in this case,

m. The radiation intensity has been enhanced by more than an order of magnitude with respect to the SASE operating without dispersion (red squares in

Figure 3). We repeated the measurements of the OK FEL pulse energy as a function of the

for different values of the laser heater energy, i.e., for different values of the induced slice energy spread, and the results are plotted in

Figure 3.

Increasing the laser heater energy provides additional energy spread that depletes the OK enhancement, as observed also in [

40], and its maximum value is obtained for smaller values of

(see gray triangles and blue diamonds curves in

Figure 3). Since, in the present scheme, the first undulator is three meters long, which means slightly more than two in gain length, the spontaneous radiation induced a very small energy modulation in comparison to the uncorrelated energy spread. Therefore, Equation (

4) is valid and the peak of the OK SASE occurs when

. By measuring the

in the cases plotted in

Figure 3, it is possible to infer the intrinsic electron energy spread

(see

Table 1).

We have calculated the theoretical OK FEL gain factor

G for each case by using Equation (

4) and taking

and the value of

listed in

Table 1. The predicted OK FEL energy per pulse has been obtained multiplying the SASE pulse energy measured for

by the calculated

G. The results are plotted in

Figure 3 (solid lines) for comparison with the measurements. A good agreement has been observed for values of the

smaller or close to the optimum value

, while, for larger

, the measured OK FEL energy is larger than expected by the 1D theory. The latter, in fact, makes the strong assumption that the beam energy distribution over a radiation wavelength is Gaussian and independent from the position along the bunch, with a second moment that we indicate as

. However, as stated in [

29], in a real electron beam, collective effects such as the microbunching instability lead to a dependence on the energy distribution from the bunch longitudinal position. We can therefore define the energy spread

as that one calculated over the longitudinal scale affecting the FEL gain, i.e., the FEL cooperation length

. In general, the energy spread

can be larger than

, leading to a reduced FEL emission. In our measurements, when the laser heater intensity is very low (red square data in

Figure 3), and the microbunching instability is not completely suppressed, experimental data and model expectations agree only qualitatively. This effect is indeed much more evident in the case of a laser heater turned completely off: the intrinsic energy spread

is very low, but the microbunching instabilities deteriorate the longitudinal phase space on the scale of the FEL cooperation length and longer wavelengths, enhancing the energy spread

and depleting the OK performance. The ideal case of a cold beam without any microbunching modulations and with a very low energy spread has been simulated by taking the slice energy spread inferred by the experimental case with the laser heater off (

) and the SASE level measured when the laser heater is tuned to suppress the microbunching and optimize the OK performance (LH energy

J). In this ideal case, the theoretical behavior of the OK versus

would provide an FEL emission much stronger than other curve (see the dashed black line in

Figure 3). On the other side, when the laser heater is strong enough to almost suppress the microbunching instability (blue diamond data), the increased energy spread

is comparable to

, and the model is in agreement with the experiment results.

We have exploited the OK setup to enhance the SASE also at 32.4 nm and at 20 nm, setting the laser heater to optimize the OK output intensity (with an energy J), and obtaining a gain factor of about 20 and 10, respectively. The optimum measured for OK FEL operating at 32.4 nm and at 20 nm are, respectively, 75 m and 35 m.

The OK enhancement to the SASE process translates to a reduced number of undulators needed to reach the FEL saturation. In order to evaluate the actual advantage of this configuration, the FEL gain length has been calculated by measuring the exponential growth of the FEL output versus the number of resonant radiators (progressively detuning each radiator undulator). The measurement was repeated for three different values of the dispersive section

, obtaining a gain length of about 1.2 m in all the cases as expected [

29]. This value is in good agreement with the GENESIS 1.3 [

41] simulation, which has been performed by using the same electron beam parameters as in the experiment.

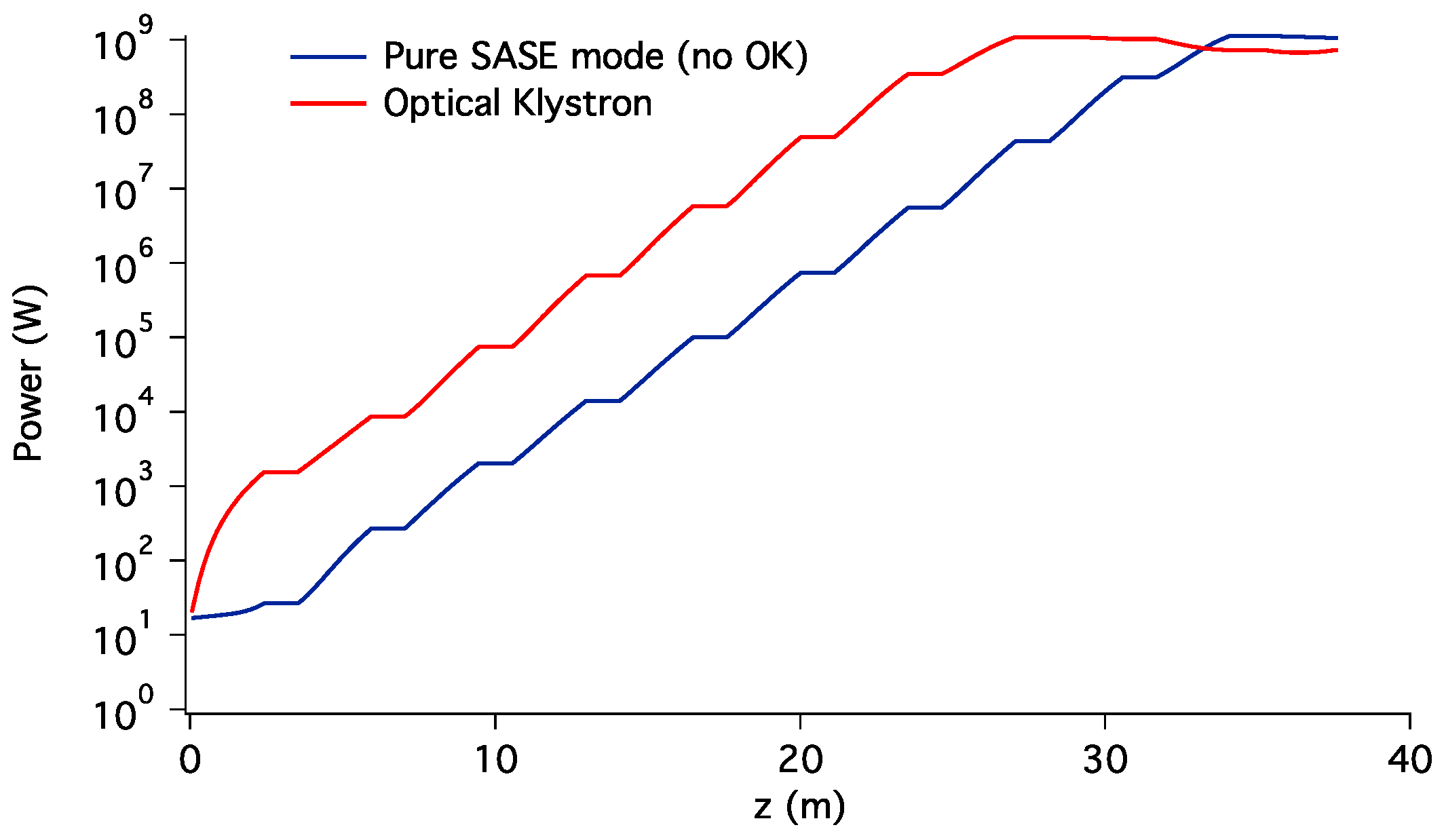

Figure 4 shows the simulated FEL power at 32.4 nm as a function of the longitudinal position along the radiator, assuming to have enough undulators to reach the FEL saturation. The optimization of the optical klystron would allow us to reach saturation savings of about 15%–20% of the total undulator length, with respect to standard SASE operation.

4. Experimental Demonstration of Multi-Stage OK SASE on FEL-2 Line at FERMI

As mentioned above, the OK scheme can be replicated in a multi-stage configuration, with alternating undulators and dispersive sections. The FERMI FEL-2 layout, designed for the double-stage cascade HGHG scheme [

15], includes three dispersive sections that are suited to test and verify the multi-stage OK enhancement to SASE in the soft X-ray regime.

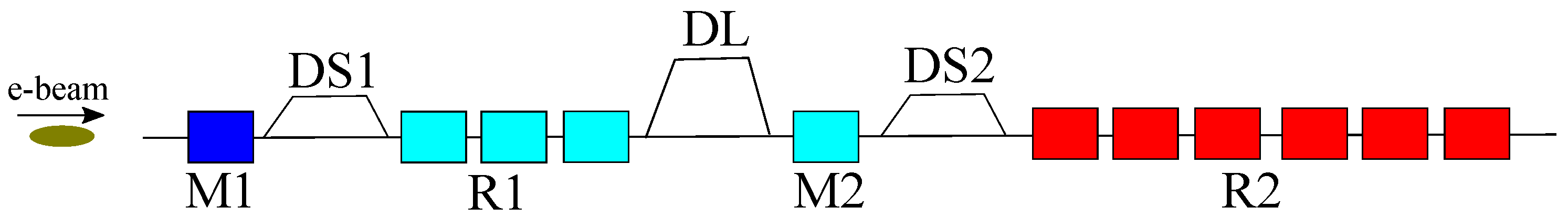

Figure 5 shows a sketch of the actual FEL-2 undulator layout.

All undulators have a variable gap allowing for tuning the magnetic field to satisfy the resonant condition in a wide wavelength range. However, the modulator M1 is designed to be resonant with the seed laser at optical wavelengths, i.e., 200–400 nm, and it cannot be tuned down to 20 nm, which is the upper limit of the spectral range of the FEL-2 final amplifier. For this reason, a first series of experiments was carried out without using M1 and the first dispersive section DS1. The rest of the undulators of R1, M2 and R2 were tuned at the same wavelength. In this setup, we have used only the two dispersive sections DL and DS2.

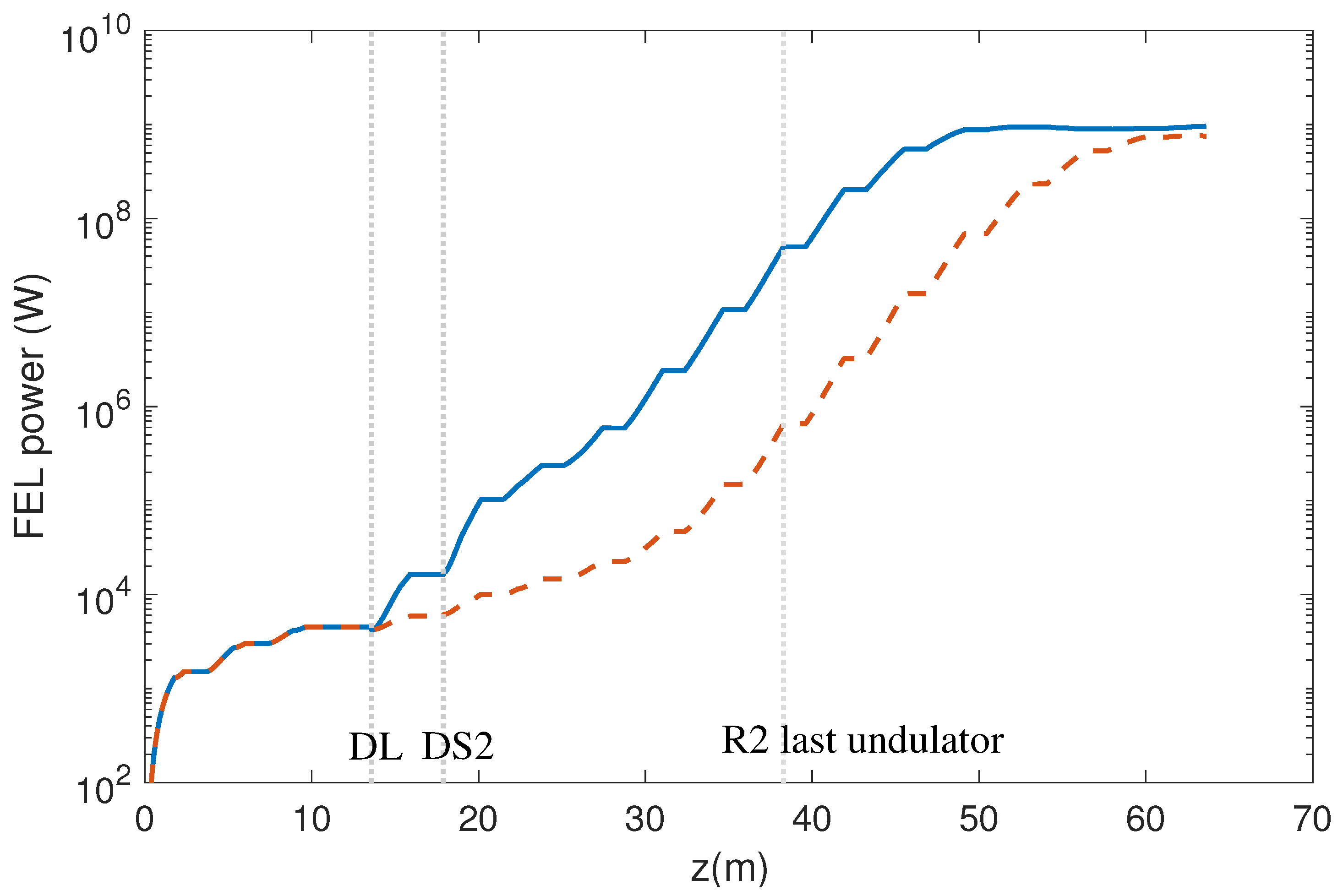

Figure 6 shows the results of GENESIS simulation of the two-stage OK scheme compared to the SASE mode without enabling any dispersions, when R1, M2 and R2 are tuned to be resonant with

nm. An ideal electron beam has been considered, with a peak current of 700 A, beam energy 1.525 GeV, slice emittance

mm mrad, and an average beam spot size along the undulator of about 70

m. By optimizing DL, the FEL power increases by about a factor 4 in M2, against the

increment of SASE with the dispersion of DL set to zero. Furthermore, setting DS2 at the optimum value enhances the FEL power in the first undulator of R2 by more than a factor 6, while, without the dispersion, the gain would be less than a factor 2. The expected output power at the end of R2 exploiting the two-stage OK at 5.3 nm is higher than without any dispersions by two orders of magnitude, and only 2–3 more undulators would be necessary to reach FEL saturation.

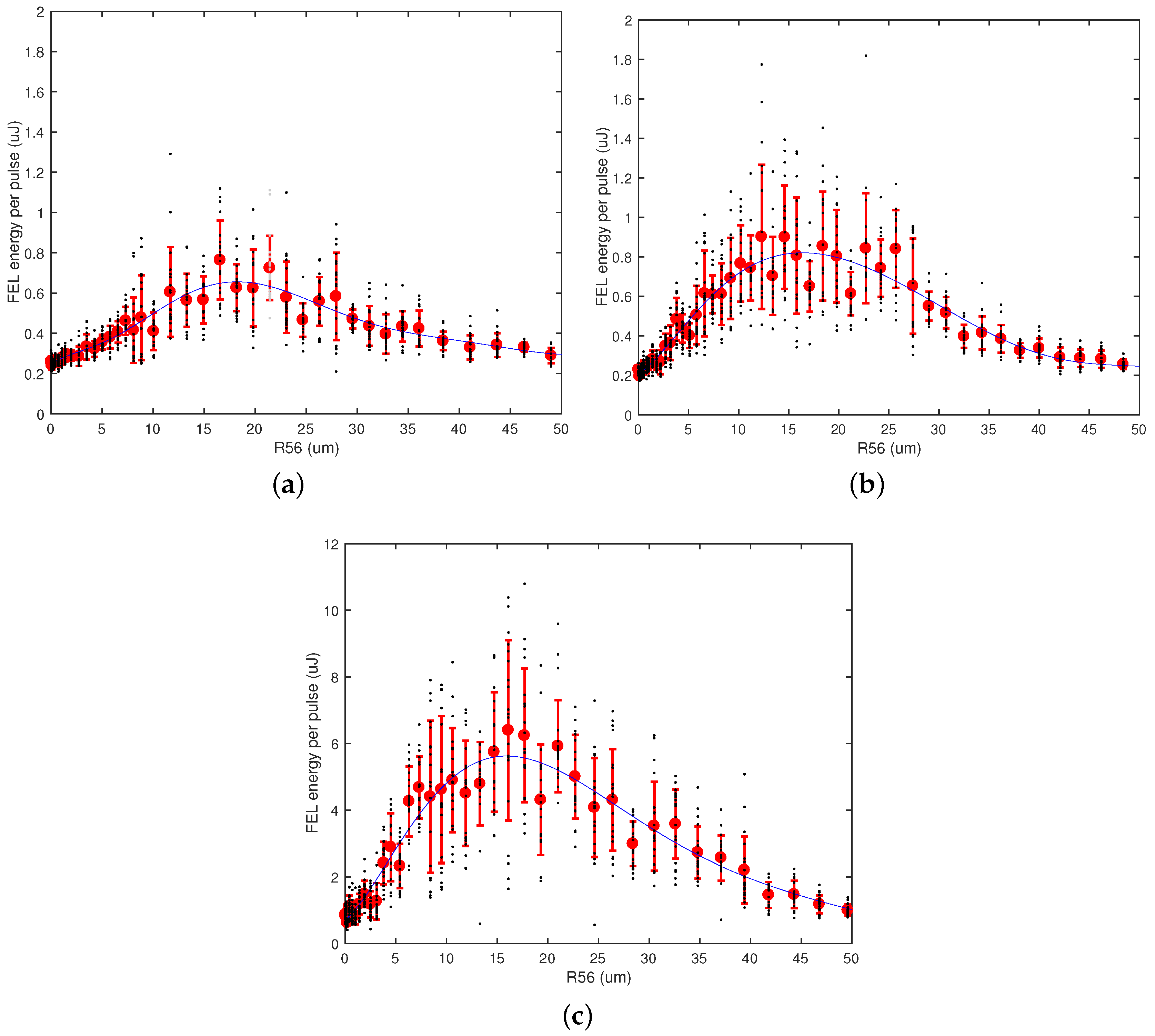

Several experiments in two-stage OK mode have been performed, and we report the case at 5.3 nm in

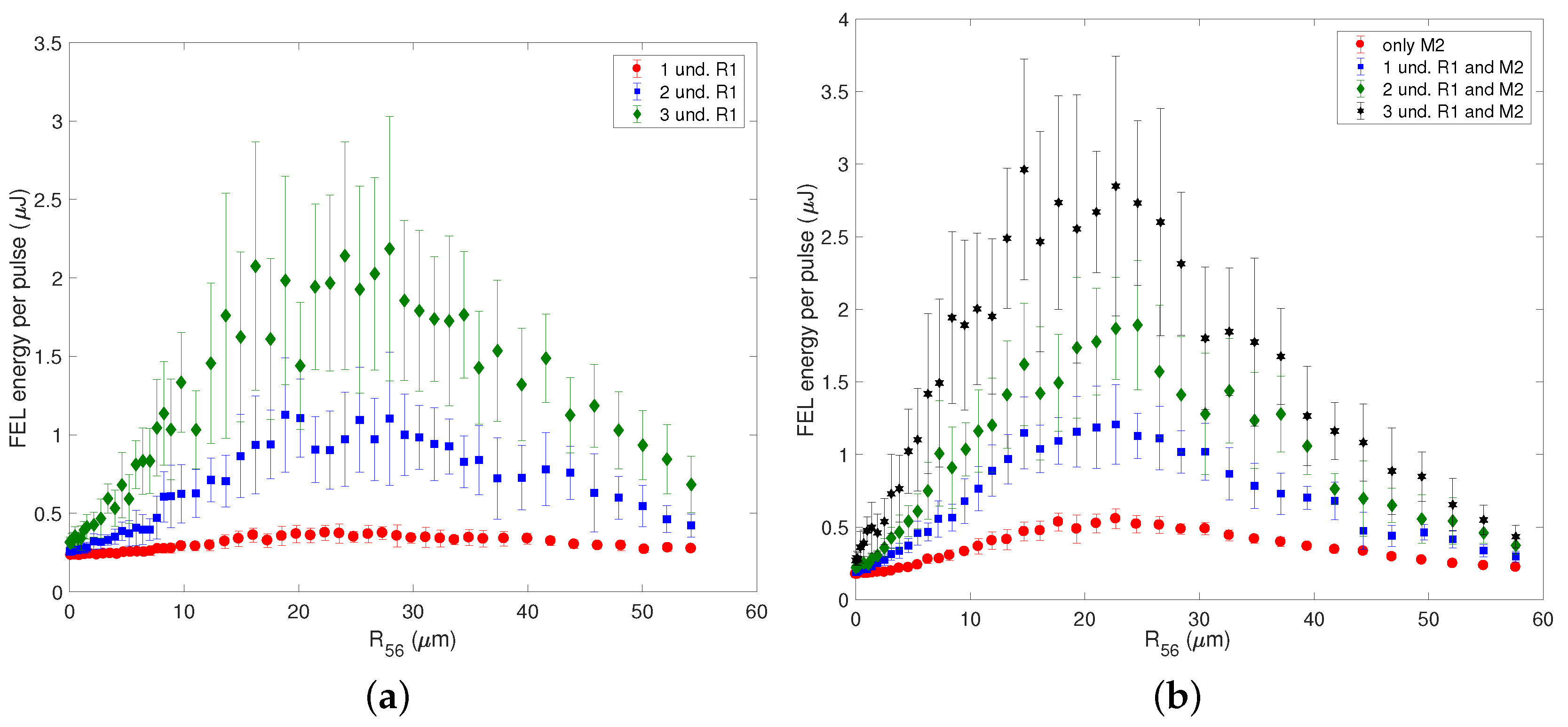

Figure 7 as an example.

When DL and DS2 are set straight, i.e.,

m, the FEL is in the SASE standard configuration. In this condition, we have measured an energy per pulse of about 0.2

J. An increase of the

of the DL (

Figure 7a) only, or similarly of the

of DS2 only (

Figure 7b), corresponds to a single-stage OK layout, as described in the previous section.

Figure 7a shows that the SASE output is enhanced by more than a factor 3 by using only DL or, alternatively, DS2. In the latter case, the FEL pulse energy is slightly higher because of the contribution of the M2 undulator to the energy modulation before the dispersive section: this increases the bunching factor at the entrance of R2, slightly reducing the value of

, which is

m, in the first case, and

m, in the second case. From the relationship

, we can estimate the intrinsic beam energy spread

. Some more measurements have been performed varying the number of undulators used before the dispersive section in order to study the effect of the energy modulation induced by the spontaneous emission. The results are reported in the

Appendix A.

A further enhancement of the pulse energy has been obtained by setting

to the optimum value of 18

m and by using DS2 for a second-stage OK.

Figure 7c shows that the two-stage OK scheme increased the FEL output by about a factor of 10 relative to the single stage OK, reaching an average energy per pulse of 6

J with isolated shots over 10

J. The optimum

is further shifted to 16

m, consistently to the augmented bunching at the entrance of R2 undulators. To demonstrate the role played by the M2 undulator, we have excluded it (by completely detuning its gap), and we have repeated the scan of DS2 with the DL set at its optimum value: the FEL intensity progressively decreased because of the overbunching induced by DS2 itself. In this layout, we have demonstrated an average enhancement of the FEL pulse energy by about a factor of 30 with the two-stage OK scheme relative to the SASE operating without any dispersions.

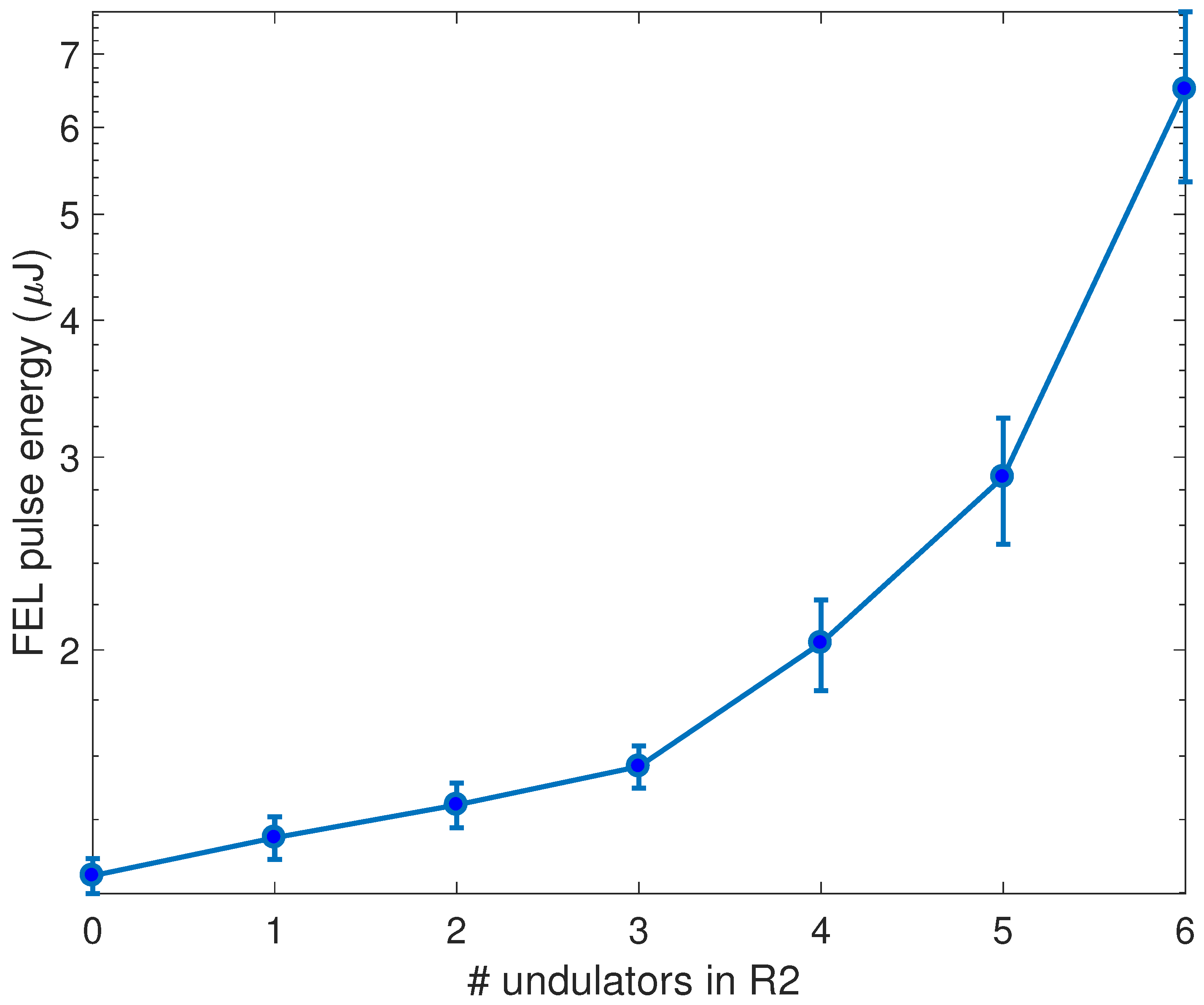

The FEL exponential growth in the two-stage OK regime has been measured as in the previous section by progressively detuning the undulators of R2, and the results are plotted in

Figure 8. Taking into account the last step-up and considering an undulator length of 2.42 m, we have estimated a gain length of about 3.0 m.

As previously explained, the modulator M1 is not tunable down to 20 nm, but its resonance can be set to one of the sub-harmonics of the FEL output wavelength

. In this layout, we may expect some contribution of the modulator and of the first dispersive section DS1 in converting the energy modulation induced in M1 in bunching at

and at its higher harmonic

.

Figure 9 shows the results of an experiment of three-stage OK realized by tuning M1 at 66 nm and R1, M2 and R2 at 4.4 nm.

Figure 9a presents the single-stage OK enhancement to SASE obtained by using the dispersive element DL: the maximum FEL intensity is achieved at

m, corresponding to an estimate of the slice energy spread

. This value is larger than what we estimated in the experiment at 5.3 nm because the larger sensitivity to the microbunching instabilities at shorter wavelengths required a more powerful laser heater, with a consequent increase of the slice energy spread. At the time of the experiment, the radiator R1 was composed of two undulators, so that the induced energy modulation before DS2 was lower than the one corresponding to the experiment shown in

Figure 7. At a wavelength of 4.4 nm, the two-stage OK increased the FEL intensity by about 30%–50% (see

Figure 9b) with respect to the single-stage OK (

Figure 9a). In this condition, the gain length is relatively long and the gain process is far from reaching the onset of saturation. However, the implementation of a three-stage OK enhanced the SASE output pulse energy (see

Figure 9c) by about a factor of two with respect to the two-stage OK mode.

In the single and multi-stage OK configuration, with all the undulators tuned at the same wavelength, there exists a clear optimum value of the dispersion

that maximizes the SASE output pulse energy. On the contrary, the optimization of DS1 with the modulator M1 tuned at a sub-harmonic of the final wavelength shows a modest sensitivity to the value of the dispersion.

Figure 9d shows the FEL pulse energy in the three-stage OK configuration as a function of the

, after optimizing DL and DS2. It is essential to set the dispersion different from zero to observe the enhancement, but the plot doesn’t show a clear maximum in the dispersion range analysed. The reason is linked to the dynamics of the bunching factor, which results from an energy modulation at the subharmonic 66 nm rather than at the final wavelength of 4.4 nm. The optimum value of the dispersion matches the condition

where

is the long wavelength of the first modulator, even if the relevant modulation for the growth of the FEL signal is the contribution at the high order harmonic

.