Comparison of CO2 Vertical Profiles in the Lower Troposphere between 1.6 µm Differential Absorption Lidar and Aircraft Measurements Over Tsukuba

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Setup

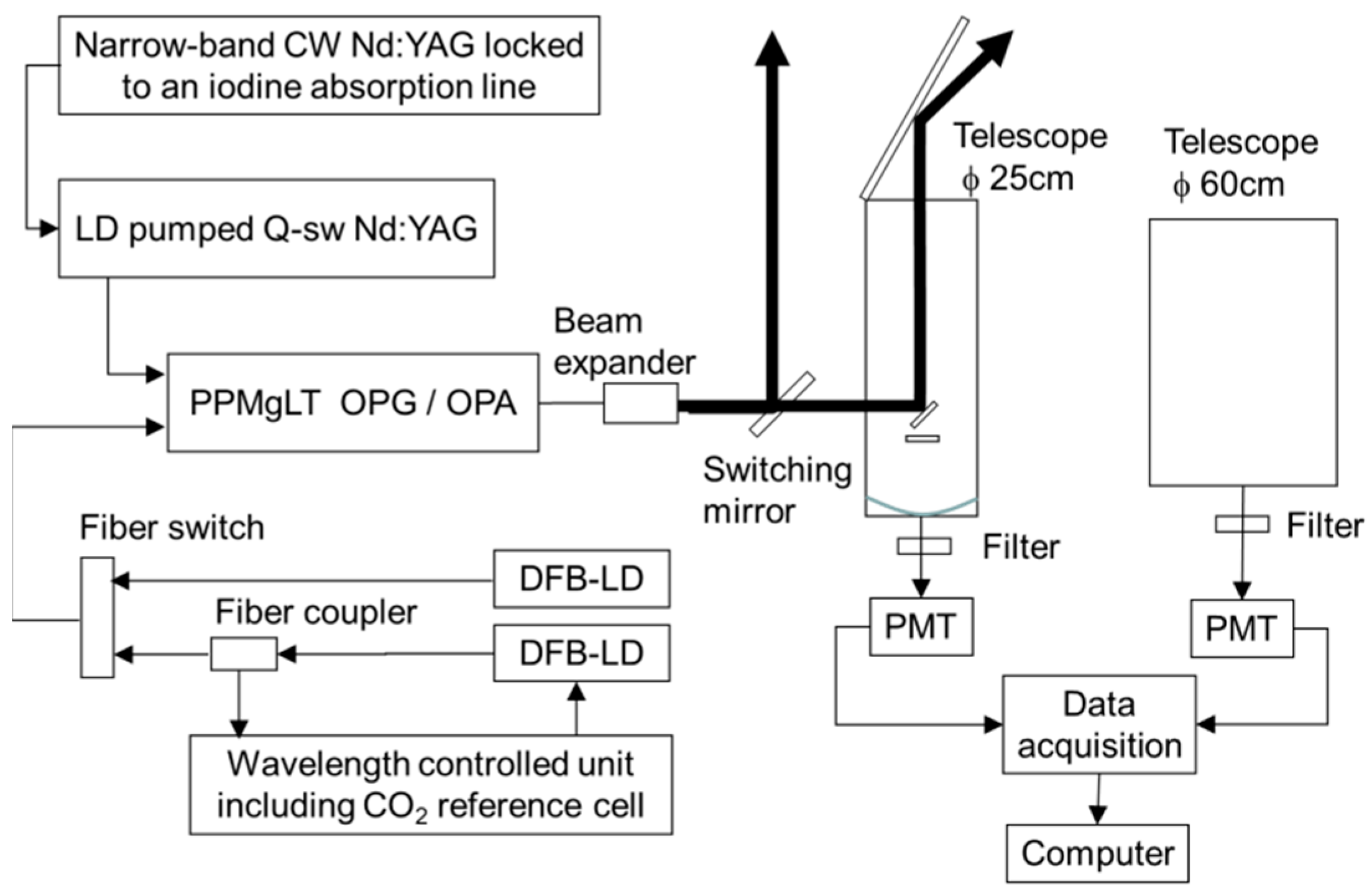

2.1. CO2 DIAL

2.2. Aircraft

3. CO2 DIAL and Aircraft Campaign

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stocker, T.F.; Qin, D.; Plattner, G.-K.; Tignor, M.; Allen, S.K.; Boschung, J.; Nauels, A.; Xia, Y.; Bex, V.; Midgley, P.M. IPCC, 2013: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental, Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showstack, R. Carbon dioxide tops 400 ppm at Mauna Loa, Hawaii. Eos. Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 2013, 94, 192. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, B.B.; Gurney, K.R.; Tans, P.P.; Sweeney, C.; Peters, W.; Bruhwiler, L.; Ciais, P.; Ramonet, M.; Bousquet, P.; Nakazawa, T.; et al. Weak Northern and Strong Tropical Land Carbon Uptake from Vertical Profiles of Atmospheric CO2. Science 2007, 316, 1732–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pales, J.C.; Keeling, C.D. The concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide in Hawaii. J. Geophys. Res. 1965, 70, 6053–6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.Y.; Matsueda, H. Measurements of atmospheric CO2 from a meteorological tower in Tsukuba, Japan. Tellus B 2001, 53, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, T.; Matsueda, H.; Sawa, Y.; Nakagawa, Y.; Hirotani, K.; Kondo, N.; Goto, K.; Nakazawa, T.; Ishikawa, K.; Ogawa, T. Worldwide measurements of atmospheric CO2 and other trace gas species using commercial airlines. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2008, 25, 1744–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Miyamoto, Y.; Morino, I.; Machida, T.; Nagahama, T.; Sawa, Y.; Matsueda, H.; Wunch, D.; Kawakami, S.; Uchino, O. Aircraft measurements of carbon dioxide and methane for the calibration of ground-based high-resolution Fourier Transform Spectrometers and a comparison to GOSAT data measured over Tsukuba and Moshiri. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2012, 5, 2003–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inoue, M.; Morino, I.; Uchino, O.; Miyamoto, Y.; Yoshida, Y.; Yokota, T.; Machida, T.; Sawa, Y.; Matsueda, H.; Sweeney, C.; et al. Validation of XCO2 derived from SWIR spectra of GOSAT TANSO-FTS with aircraft measurement data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 9771–9788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browell, E.V.; Wilkerson, T.D.; Mcilrath, T.J. Water vapor differential absorption Lidar development and evaluation. Appl. Opt. 1979, 18, 3474–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbrecht, W.; Rothe, K.W.; Walther, H. Lidar setup for daytime and nighttime probing of stratospheric ozone and measurements in polar and equatorial regions. Appl. Opt. 1989, 28, 3616–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repasky, K.S.; Moen, D.; Spuler, S.; Nehrir, A.R.; Carlsten, J.L. Progress towards an autonomous field deployable diode-laser-based differential absorption Lidar (DIAL) for profiling water vapor in the lower troposphere. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 6241–6259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, G.J.; Barnes, B.W.; Petros, M.; Beyon, J.Y.; Amzajerdian, F.; Yu, J.; Davis, R.E.; Ismail, S.; Vay, S.; Kavaya, M.J.; et al. Coherent differential absorption Lidar measurements of CO2. Appl. Opt. 2004, 43, 5092–5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorani, L.; Santoro, S.; Parracino, S.; Nuvoli, M.; Minopoli, C.; Aiuppa, A. Volcanic CO2 detection with a DFM/OPA-based Lidar. Opt. Lett. 2015, 40, 1034–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queiβer, M.; Granieri, D.; Burton, B. A new frontier in CO2 flux measurements using a highly portable DIAL laser system. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadiou, E.; Dherbecourt, J.B.; Gorju, G.; Melkonian, J.M.; Godard, A.; Pelon, J.; Raybaut, M. Atmospheric CO2 measurements with a 2-μm DIAL instrument. EPJ Web Conf. 2018, 176, 05045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refaat, T.F.; Singh, U.N.; Petros, M.; Remus, R.; Yu, J. Self-calibration and laser energy monitor validations for a double-pulsed 2-μm CO2 integrated path differential absorption Lidar application. Appl. Opt. 2015, 54, 7240–7251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibert, F.; Edouart, D.; Cénac, C.; Le Mounier, F.; Dumas, A. 2-μm Ho emitter-based coherent DIAL for CO2 profiling in the atmosphere. Opt. Lett. 2015, 40, 3093–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, Y.; Nagasawa, C.; Abo, M. Development of 1.6 μm DIAL using OPG/OPA transmitter for measuring atmospheric CO2 concentration profiles. Appl. Opt. 2017, 56, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, S.; Browell, E.V. Airborne and spaceborne Lidar measurementfs of water vapor profiles: a sensitivity analysis. Appl. Opt. 1989, 28, 3603–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Winderlich, J.; Gerbig, C.; Hoefer, A.; Rella, C.W.; Crosson, E.R.; Van Pelt, A.D.; Steinbach, J.; Kolle, O.; Beck, V.; et al. High-accuracy continuous airborne measurements of greenhouse gases (CO2 and CH4) using the cavity ring-down spectroscopy (CRDS) technique. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2010, 3, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nara, H.; Tanimoto, H.; Tohjima, Y.; Mukai, H.; Nojiri, Y.; Katsumata, K.; Rella, C.W. Effect of air composition (N2, O2, Ar, and H2O) on CO2 and CH4 measurement by wavelength-scanned cavity ring-down spectroscopy: calibration and measurement strategy. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2012, 5, 2689–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohyama, H.; Kawakami, S.; Tanaka, T.; Morino, I.; Uchino, O.; Inoue, M.; Sakai, T.; Nagai, T.; Yamazaki, A.; Uchiyama, A.; Fukamachi, T.; et al. Observations of XCO2 and XCH4 with ground-based high-resolution FTS at Saga, Japan, and comparisons with GOSAT products. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2015, 8, 5263–5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Low-Altitude | High-Altitude | |

|---|---|---|

| Pulse Energy | 6 mJ | |

| Laser Wavelength | On: 1572.992 nm, Off: 1573.137 nm | |

| Telescope Diameter | 25 cm | 60 cm |

| Interference Filter | 1.0 nm FWHM | |

| Quantum Efficiency | 2 % | 8 % |

| Detection Scheme | Photon counting mode | |

| Altitude [m] | Vertical Resolution [m] | CO2 DIAL [ppm] | Relative Error (CO2 DIAL) [ppm] | Aircraft (CRDS) [ppm] | *Difference [ppm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1560 | 236 (low-altitude) | 401.36 | 1.59 | 401.83 | −0.47 |

| 1797 | 400.16 | 1.79 | 400.68 | −0.51 | |

| 2033 | 398.97 | 2.10 | 400.47 | −1.50 | |

| 2269 | 398.73 | 2.16 | 400.01 | −1.28 | |

| 3002 | 590 (high-altitude) | 398.43 | 1.93 | 399.50 | −1.07 |

| 3599 | 399.44 | 2.03 | 399.08 | 0.37 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shibata, Y.; Nagasawa, C.; Abo, M.; Inoue, M.; Morino, I.; Uchino, O. Comparison of CO2 Vertical Profiles in the Lower Troposphere between 1.6 µm Differential Absorption Lidar and Aircraft Measurements Over Tsukuba. Sensors 2018, 18, 4064. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18114064

Shibata Y, Nagasawa C, Abo M, Inoue M, Morino I, Uchino O. Comparison of CO2 Vertical Profiles in the Lower Troposphere between 1.6 µm Differential Absorption Lidar and Aircraft Measurements Over Tsukuba. Sensors. 2018; 18(11):4064. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18114064

Chicago/Turabian StyleShibata, Yasukuni, Chikao Nagasawa, Makoto Abo, Makoto Inoue, Isamu Morino, and Osamu Uchino. 2018. "Comparison of CO2 Vertical Profiles in the Lower Troposphere between 1.6 µm Differential Absorption Lidar and Aircraft Measurements Over Tsukuba" Sensors 18, no. 11: 4064. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18114064

APA StyleShibata, Y., Nagasawa, C., Abo, M., Inoue, M., Morino, I., & Uchino, O. (2018). Comparison of CO2 Vertical Profiles in the Lower Troposphere between 1.6 µm Differential Absorption Lidar and Aircraft Measurements Over Tsukuba. Sensors, 18(11), 4064. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18114064