Flexible Virtual Reality System for Neurorehabilitation and Quality of Life Improvement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Neurological Disorders and the Classical Treatment

- Performing movements on the rhythm of the music, which can be both motivating and can facilitate the exercises;

- Applying guiding markers and limits (either visual, auditory or haptic)—this can be achieved with special glasses/headsets and sensors, which can help patients maintain the same pace and continue exercising;

- Staying hydrated (as neurons responsible for thirst are also affected);

- Perform physical exercises somewhere around noon (stiffness is increased in the morning, tiredness occurs in the evening).

- Flaccid stage—when the patient presents no muscle tone or voluntary movement, some of their reflexes disappear; correcting posture and applying therapeutic massage are used for maintaining joint and muscular integrity;

- Spastic stage—after approximately 3 weeks since the occurrence of the stroke, muscle tone is increased, and voluntary movement control starts to appear; this stage includes kinetic rehabilitation programs, based on sensory-motor techniques, exercises for increasing muscular force and movement amplitude, as well as balance and posture; some of the used techniques are based on altering perception—mirror therapy (reflecting the movement of a non-affected limb over the affected one, creating the illusion of movement) [17], virtual reality therapy (virtual limbs created in the virtual environment, with real movements performed repeatedly, and usually augmented in the virtual world)—or on stimulation (muscular or cerebral stimulation).

- Chronic/recovered stage—the motor deficit is established; therefore, it is very hard to recover at this stage; therapy is needed for health maintenance.

3. ICT Solutions for Neurological Disorders Treatment

“neurorehabilitation” OR “neurological rehabilitation”) AND “virtual reality”)

4. Our System

4.1. System’s Functionalities

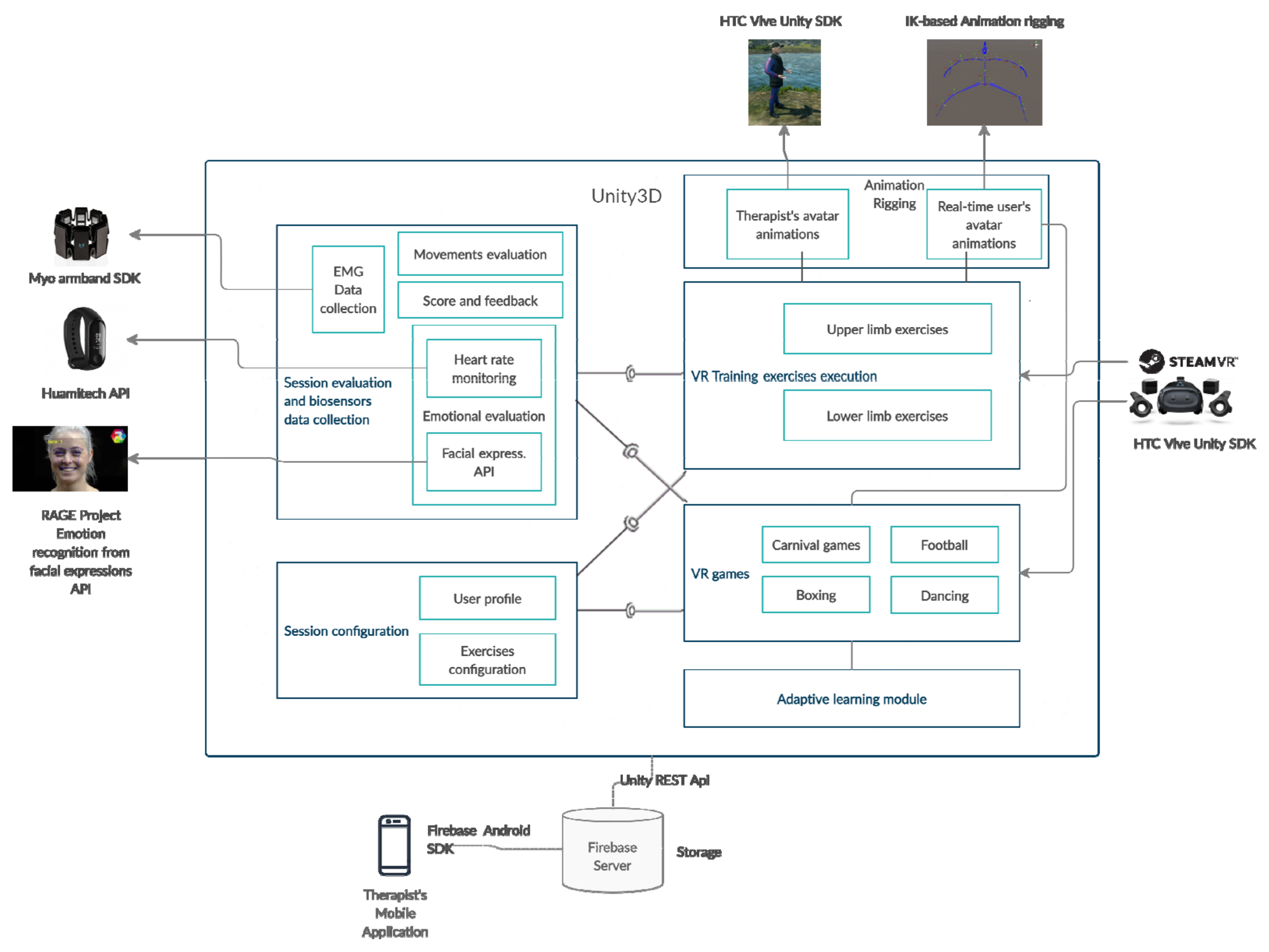

4.2. System’s Architecture

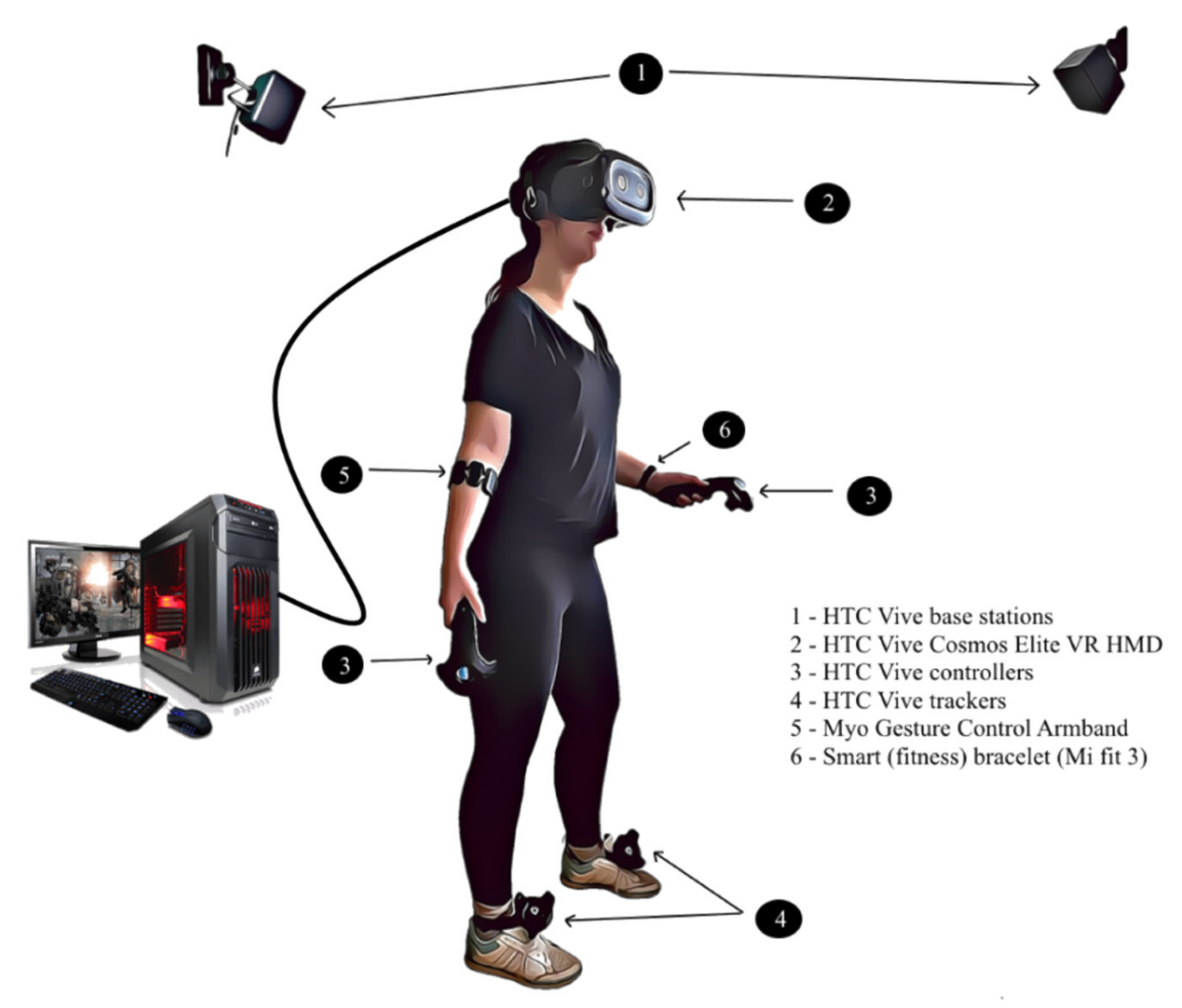

4.2.1. Hardware Components

4.2.2. Software Components

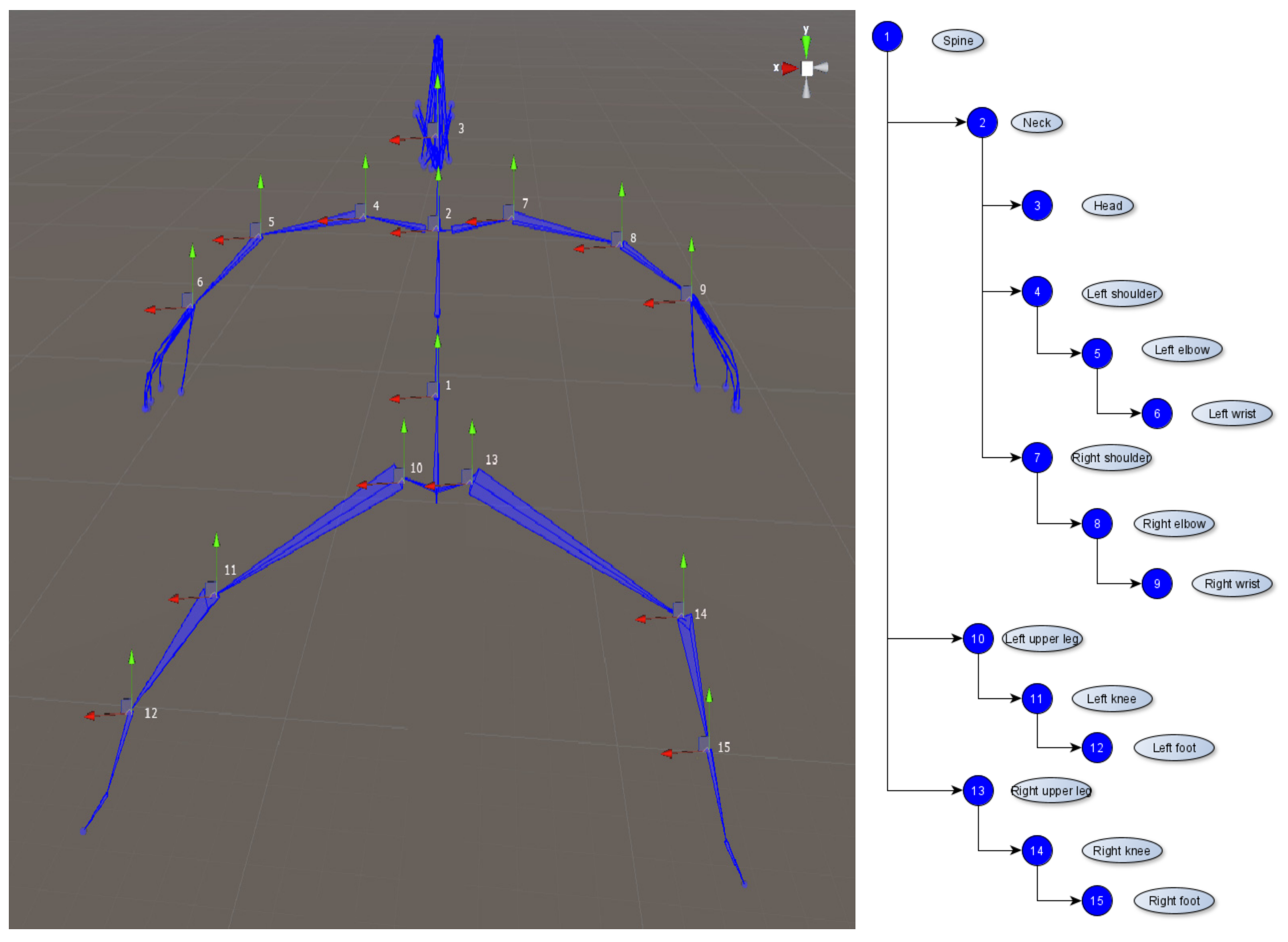

4.3. Avatars Animations

4.3.1. Real Time User’s Avatar Animation

4.3.2. Therapist’s Avatar Animations

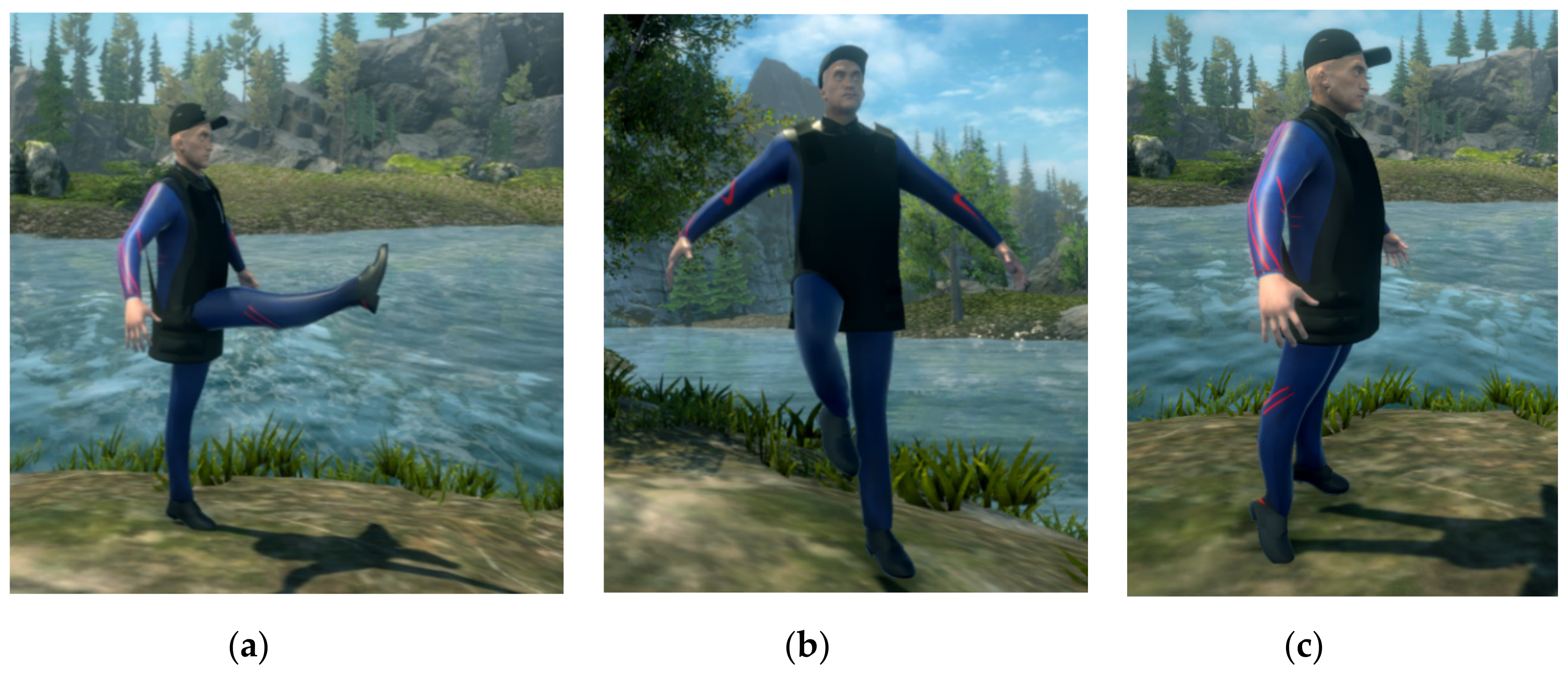

4.4. VR Training Exercises Execution

- Flexion 0°–90°, extension 90°–0° of the shoulder—starting position with the arms by the patient’s side, palms facing downward (shoulder angle 0°); each arm should be lifted so that the shoulder joint is at 90° in the sagittal plane;

- Flexion 90°–180°/extension 180°–90°of the shoulder—second part of the previous exercise, on the segment 90°–180° in the sagittal plane (starting position with both arms in front, at 90°);

- Abduction 0°–90°/Adduction 90°–0° of the shoulder—starting position with arms hanging straight, in a natural way; each arm should be lifted so that the shoulder joint is at 90° in the frontal plane.

- Extension/flexion of the forearm—starting position with the arms by the patient’s side, palms facing upward (supination); the forearm should be flexed so that the elbow joint reaches at least 145° (up to 160°) (in the sagittal plane). The extension is represented by bringing the forearm to the initial position (elbow angle 0°);

- Pronation/supination of the forearm—supination and pronation are rotational movements in the transversal plane (along the longitudinal axis of the limb), supination representing the upwards movement of the palm, and pronation the downward movement [15] (p. 41). The movement is performed from 0° to 90° (supination), respectively, from 0° to −90° (pronation), the neutral position being the one with the arms oriented and fully stretched forward, with the thumb oriented upwards;

- Arm pushing (downwards)—training both elbow and fist joints; from a relaxed position, with the hands close to the chest and the forearm oriented horizontally so that the elbow joint forms an angle of approximately 90° in flexion, a pushing motion is made towards the ground until the forearm is fully extended (elbow joint angle becomes 0°);

- Arm pushing (front)—training both elbow and fist joints; from a relaxed position, with hands raised at the shoulder level and the forearm oriented vertically (hands close to face), a forward pushing movement is performed until the forearm is perfectly extended (elbow joint angle becomes 0°), and the fist joint is at least 60° in extension in the sagittal plane.

- Fist extension (Figure 13a)—with the arms stretched forward, from a pronation position, the fist joint must be rotated from 0° to 70° in the sagittal plane;

- Fist adduction (Figure 13b)—similar with the waving gesture; from the extension position presented in the previous exercise, the joint must be adducted with a maximum of 50°–55° in the frontal plane (exterior rotation).

- Spinning wheel—classical exercise especially for Parkinson’s disease, where the movement coordination is tested. The initial position is the same from the “arm pushing (downwards)” presented previously. The symmetry of the execution of the movements is evaluated (the successive rotation transforms of the arm joints must have comparable values), so that the joint of each elbow forms an angle of at least 45° in the sagittal plane throughout the movement; the physical resistance is measured (for how long can the user execute the exercise without losing focus or coordination);

- Boxing training (jab punches) (Figure 13c)—this exercise aims to train the user for the boxing game (Section 4.5), with the most basic movement of this sport—the jab punch. The starting position is similar to that of the exercise entitled “arm pushing (front)”, but the hand is relaxed or with a clenched fist, not in extension. The user must make a pushing movement towards an imaginary adversary, at chest or face level, with each arm at the time, until the forearm is perfectly extended; when one arm is pushed forward, the other returns to the neutral position (“guard”); the physical resistance (the time of repetition of the hits without interruption) and the speed of the hits are evaluated.

- Hip flexion (0–90°)—the lower limb should be raised forward, keeping it perfectly stretched so that the hip joint approaches 90° in the sagittal plane;

- Hip abduction—the lower limb must be raised to the side, keeping it perfectly stretched so that the hip joint approaches 45° in the frontal plane; the patient’s pelvis must remain still and not tilt to the opposite side.

- Knee flexion (forward)—the lower limb should be raised forward, with the knee flexed in the sagittal plane;

- Knee flexion (backward)—the previous exercise can be executed also with the lower limb oriented backwards; both movements should consist of at least 75°–80° knee rotation in the sagittal plane.

- Ankle flexion/extension—similar to a “toe stand” followed by “heel stand”; standing on toes is equivalent to an extension of about 45° in the sagittal plane; the flexion is represented by returning to the initial position, with a slight bend on the heels (maximum 20°).

4.5. Training in VR Games

- Hit targets—picking up a ball and throwing it to hit a tower of cans. The exercises of shoulder flexion–extension (0°–180°) from the tutorial are practiced now, as well as actions of grabbing/releasing of objects. The actions are performed in a very natural manner. Clenching the fist will activate the controller’s grab buttons, respectively, Myo’s specific gesture, for picking up a ball; the user must lift their arm and launch the ball at a certain speed; by releasing the grab buttons/unclenching the fist, the ball will be launched. Various levels of difficulty are obtained through different a number of hit targets or different distances between the player and the targets. Picking up the ball is simulated through vibrations (from the controller or the armband).

- Ball directing—a ball must be directed on a table which has a ramp at its end and land in holes with different scores. This game practices movements of the elbow from the tutorial, and a new ball will be generated in the person’s hand, which is the grip buttons of the controller being pressed. Similar launching actions are performed when the grip buttons are released. Difficulty is varied through the maximum number of available balls or through the distance between the player and the table’s end. Picking up the ball is simulated through vibrations (from the controller or the armband).

- Whack-a-mole—the user must hit as many moles as they can using a hammer, in 60 s. Both hand and elbow tutorial movements are being trained. The HTC Vive scenario includes the use of a 3 × 3 matrix of moles. Various difficulty levels are obtained by changing the moles’ spawning frequency and the duration until they are “hiding” back in their holes. Hitting a mole is simulated through vibrations (from the controller or the armband).

- Boxing—the user must perform different boxing techniques (guard, jab, cross punch, hook, uppercut), as performed by a virtual trainer. There are two scenarios—in a boxing ring with a mannequin and in front of a punching bag (heavier than the mannequin). The score is calculated based on the number of punches thrown in one minute. The contact with the target is simulated through vibrations (from the controller or the armband).

- Football—ball shooting to hit the goal from a fixed position. All lower limb joints are being trained. Various degrees of difficulty include varying the distance to the goal (e.g., penalty, free kick), with or without a goalkeeper or a wall and hitting from a central or lateral position. Hitting the ball is simulated through vibrations of the tracker.

- Dancing—similar to the “arcade dancing games”. All lower limb joints are being trained. The user must touch colorful squares on the floor that are being lit in the rhythm of the music, as shown on an arcade screen. Different songs need different speeds of performing the steps and vary the difficulty.

4.6. Adaptive Learning Algorithm

4.7. Session Configuration, Evaluation and Data Collection

5. Preliminary Results and Discussion

5.1. Testing Procedure

5.2. Synthetic Results

5.3. Feedback and Future Improvements

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BCI | Brain–computer interface |

| DOI | Digital object identifier |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| ICF | International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health |

| IK | Inverse kinematics |

| INREX-VR | Immersive Neurorehabilitation Exercises Using Virtual Reality |

| ISI | International Scientific Index |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses |

| ROM | Range of motion |

| SDK | Software development kit |

| VR | Virtual reality |

Appendix A

| Exercise | Excellent (5) | Good (4) | Fair (3) | Poor (2) | Very Poor (1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper limb | |||||

| Shoulder flexion Shoulder abduction Elbow flexion Elbow supination Arm pushing Fist extension | >80° | 65°–80° | 50°–65° | 30°–50° | <30° |

| >80° | 60°–80° | 40°–60° | 25°–40° | <25° | |

| >100° | 80°–100° | 40°–80° | 20°–40° | <20° | |

| 75°–90° | 50°–75° | 35°–50° | 20°–35° | <20° | |

| >60° | 45°–60° | 30°–45° | 15°–30° | <15° | |

| >70° | 50°–70° | 35°–50° | 20°–35° | <20° | |

| Lower limb | |||||

| Hip flexion | >75° | 45°–75° | 30°–45° | 15°–30° | <15° |

| Hip abduction | >45° | 30°–45° | 20°–30° | 10°–20° | <10° |

| Knee flexion | >90° | 50°–90° | 30°–50° | 15°–30° | <15° |

| Ankle flexion | >35° | 20°–35° | 10°–20° | 5°–10° | <5° |

| Game | Excellent (5) | Good (4) | Fair (3) | Poor (2) | Very Poor (1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper limb | |||||

| Hit targets (cans) | Reaching level “difficult” where at least one can is hit | All easy levels completed and half of the targets from a medium level are hit | All easy levels completed and reached medium | 2–3 cans hit in one easy level | 0–1 can hit in one easy level |

| Ball directing | >700 points | 500–700 points | 300–500 points | 100–300 points | <100 points |

| Whack-a-mole—easy | >95% hit accuracy | 75–95% hit accuracy | 55–75% hit accuracy | 35–55% hit accuracy | <35% hit accuracy |

| Whack-a-mole—medium | >90% hit accuracy | 70–90% hit accuracy | 50–70% hit accuracy | 30–50% hit accuracy | <30% hit accuracy |

| Whack-a-mole—hard | >85% hit accuracy | 65–85% hit accuracy | 45–65% hit accuracy | 25–45% hit accuracy | <25% hit accuracy |

| Boxing—ring | >50 hits/each fist | 40–50 hits/each fist | 30–40 hits/each fist | 20–30 hits/each fist | <20 hits/each fist |

| Boxing—bag | >40 hits/each fist | 30–40 hits/each fist | 20–30 hits/each fist | 10–20 hits/each fist | <10 hits/each fist |

| Lower limb | |||||

| Football—penalty | >10 goals | 7–10 goals | 4–7 goals | 2–4 goals | <2 goals |

| Football—free kick | >8 goals | 5–8 goals | 2–5 goals | 1–2 goals | 0 goals |

References

- United Nations—Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Ageing 2019: Highlights; United Nations—Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–11.

- Feigin, V.L.; Nichols, E.; Alam, T.; Bannick, M.S.; Beghi, E.; Blake, N.; Culpepper, W.J.; Dorsey, E.R.; Elbaz, A.; Ellenbogen, R.G.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cella, D.; Nowinski, C.; Peterman, A.; Victorson, D.; Miller, D.; Lai, J.S.; Moy, C. The neurology quality-of-life measurement initiative. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ward, A.B.; Gutenbrunner, C. Physical and rehabilitation medicine in Europe. J. Rehabil. Med. 2006, 38, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carroll, W.M. The global burden of neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 418–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tieri, G.; Morone, G.; Paolucci, S.; Iosa, M. Virtual reality in cognitive and motor rehabilitation: Facts, fiction and fallacies. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2018, 15, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MedLife Glossary. Parkinson’s Disease: Everything You Need to Know, from Causes and Symptoms to Treatment and Prevention. Available online: https://www.medlife.ro/glosar-medical/afectiuni-medicale/boala-parkinson-cauze-simptome-tratament (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Bajenaru, P.D.O. Guide of Diagnosis and Treatment in Neurology, Chapter Guide of Diagnosis in Parkinson’s Disease; Editura Amaltea: Bucharest, Romania, 2010; pp. 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Mateescu, R.R. Neurological Disorders for All; MAST: Bucharest, Romania, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag, K.C.; Song, B.; Lee, N.; Jung, J.H.; Cha, Y.; Leblanc, P.; Neff, C.; Kong, S.W.; Carter, B.S.; Schweitzer, J.; et al. Pluripotent stem cell-based therapy for Parkinson’s disease: Current status and future prospects. Prog. Neurobiol. 2018, 168, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddard-Bennett, T.; Reijo Pera, R. Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease through Personalized Medicine and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cells 2019, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Todorescu, A. ReginaMaria Hospital Website, The Importance of Movement in Parkinson’s Disease. 2016. Available online: https://www.reginamaria.ro/articole-medicale/importanta-miscarii-boala-parkinson (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Dahnovici, R.M. Hemorrhagic Strokes Clinical, Histological and Immunohistochemical Study; University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Craiova: Craiova, Romania, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Băjenaru, O. Diagnosis and Treatment Guide for Cerebrovascular Diseases. In Romanian Translation of the European Guide (ESO) for Transient Ischemic Attack and Ischemic Stroke; Published in the Official Monitor no. 608/2009; Romanian Ministry of Health: Bucharest, Romania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sbenghe, T. Prophylactic Therapeutic and Recovery Kinetology. Ed. Med. 1987, 1, 28–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, J. Physio-kinetotherapy and medical recovery in musculoskeletal disorders. Ed. Med. 2018, 1, 40128. [Google Scholar]

- Ferche, O.; Moldoveanu, A.; Cinteza, D.; Toader, C.; Moldoveanu, F.; Voinea, A.; Taslitchi, C. From neuromotor command to feedback: A survey of techniques for rehabilitation through altered perception. In Proceedings of the 2015 E-Health and Bioengineering Conference (EHB), Lasi, Romania, 19–21 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arseni, C.H.; Arseni, H.; Aldea, T.O. Inferior Lumbar Disc Herniation—Current Diagnostic and Treatment Problems; Ed. Didactica si Pedagogica: Bucharest, Romania, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, D.; Fauci, A.; Kasper, D.; Hauser, S.; Jameson, J. Harrisons Manual of Medicine, 18th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education/Medical: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.C. Diabetic Neuropathy: Clinical Management. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2008, 98, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Howard, G.; Goff, D.C. Population shifts and the future of stroke: Forecasts of the future burden of stroke. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1268, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.; Onuma, O.; Owolabi, M.; Sachdev, S. Stroke: A Global Response is Needed. Bull. World Health Organ. 2016, 94, 634–634A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westlake, K.P.; Patten, C. Pilot study of Lokomat versus manual-assisted treadmill training for locomotor recovery post-stroke. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2009, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahn, L.E.; Kahn, L.E.; Averbuch, M.; Rymer, W.Z.; Reinkensmeyer, D.J. Comparison of Robot-Assisted Reaching to Free Reaching in Promoting Recovery from Chronic Stroke. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics “Integration of Assistive Technology in the Information Age”, Evry, France, 25–27 April 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Carpino, G.; Pezzola, A.; Urbano, M.; Guglielmelli, E. Assessing Effectiveness and Costs in Robot-Mediated Lower Limbs Rehabilitation: A Meta-Analysis and State of the Art. J. Healthc. Eng. 2018, 2018, 7492024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wade, E.; Winstein, C.J. Virtual reality and robotics for stroke rehabilitation: Where do we go from here? Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2011, 18, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, J.; Solis-Escalante, T.; Scherer, R.; Neuper, C.; Müller-Putz, G. It’s how you get there: Walking down a virtual alley activates premotor and parietal areas. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epelde, G.; Valencia, X.; Ardanza, A.; Fanchon, E.; De Mauro, A.; Rueda, F.M.; Carrasco, E.; Rajasekharan, S. Virtual arm representation and multimodal monitoring for the upper limb robot assisted teletherapy. In Proceedings of the Neurotechnix 2013—International Congress on Neurotechnology, Electronics and Informatics, Algarve, Portugal, 18–20 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Scorza, D.; de Los Reyes, A.; Cortés, C.; Ardanza, A.; Bertelsen, A.; Ruiz, O.E.; Gil, A.; Flórez, J. Upper Limb Robot Assisted Rehabilitation Platform Combining Virtual Reality, Posture Estimation and Kinematic Indices. In Biosystems and Biorobotics; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1187–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, F.; Naros, G.; Gharabaghi, A. Closed-loop task difficulty adaptation during virtual reality reach-to-grasp training assisted with an exoskeleton for stroke rehabilitation. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saposnik, G.; Teasell, R.; Mamdani, M.; Hall, J.; McIlroy, W.; Cheung, D.; Thorpe, K.E.; Cohen, L.G.; Bayley, M. Effectiveness of virtual reality using wii gaming technology in stroke rehabilitation: A pilot randomized clinical trial and proof of principle. Stroke 2010, 41, 1477–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carregosa, A.A.; Aguiar dos Santos, L.R.; Masruha, M.R.; da S. Coêlho, M.L.; Machado, T.C.; Souza, D.C.B.; Passos, G.L.L.; Fonseca, E.P.; da S Ribeiro, N.M.; Melo, A.S. Virtual Rehabilitation through Nintendo Wii in Poststroke Patients: Follow-Up. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2018, 27, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Ribeiro, N.M.; Dominguez Ferraz, D.; Pedreira, É.; Pinheiro, Í.; Da Silva Pinto, A.C.; Gomes Neto, M.; dos Santos, L.R.A.; Pozzato, M.G.G.; Pinho, R.S.; Masruha, M.R. Virtual rehabilitation via Nintendo Wii® and conventional physical therapy effectively treat post-stroke hemiparetic patients. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2015, 22, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.Y.; Yang, Y.R.; Cheng, S.J.; Wu, Y.R.; Fuh, J.L.; Wang, R.Y. Virtual Reality-Based Training to Improve Obstacle-Crossing Performance and Dynamic Balance in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2015, 29, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloréns, R.; Alcañiz, M.; Colomer, C.; Navarro, D.; Baynat, S. Balance Recovery Through Virtual Stepping Exercises Using Kinect Skeleton Tracking: A Follow-Up Study with Chronic Stroke Patients. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2012, 181, 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.J.; Park, H.K.; Kim, H.J.; Lim, T.; Ku, J.; Cho, S.; Kim, S.I.; Park, E.S. Upper extremity rehabilitation of stroke: Facilitation of corticospinal excitability using virtual mirror paradigm. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2012, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moldoveanu, A.; Ferche, O.M.; Moldoveanu, F.; Lupu, R.G.; Cinteza, D.; Constantin Irimia, D.; Toader, C. The TRAVEE system for a multimodal neuromotor rehabilitation. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 8151–8171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.J.; Lichter, M.D.; Ellington, A.; White, M.; Armstead, K.; Patrie, J.T.; Diamond, P.T. Virtual Activities of Daily Living for Recovery of Upper Extremity Motor Function. IEEE Trans. Neural. Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2018, 26, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva de Sousa, J.C.; Torriani-Pasin, C.; Tosi, A.B.; Fecchio, R.Y.; Costa, L.A.R.; de Moraes Forjaz, C.L. Aerobic Stimulus Induced by Virtual Reality Games in Stroke Survivors. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiper, P.; Baba, A.; Alhelou, M.; Pregnolato, G.; Maistrello, L.; Agostini, M.; Turolla, A. Assessment of the cervical spine mobility by immersive and non-immersive virtual reality. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2020, 51, 102397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego, A.; Latorre, J.; Alcañiz, M.; Llorens, R. Embodiment and Presence in Virtual Reality After Stroke. A Comparative Study with Healthy Subjects. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi-Gheidari, N.; Hernandez, A.; Archambault, P.S.; Higgins, J.; Poissant, L.; Kairy, D. Feasibility, safety and efficacy of a virtual reality exergame system to supplement upper extremity rehabilitation post-stroke: A pilot randomized clinical trial and proof of principle. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, A.; Darakjian, N.; Finley, J.M. Walking in fully immersive virtual environments: An evaluation of potential adverse effects in older adults and individuals with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2017, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mihajlovic, Z.; Popovic, S.; Brkic, K.; Cosic, K. A system for head-neck rehabilitation exercises based on serious gaming and virtual reality. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2018, 77, 19113–19137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Herrera-Baeza, P.; Cano-de-la-Cuerda, R.; Oña-Simbaña, E.D.; Palacios-Ceña, D.; Pérez-Corrales, J.; Cuenca-Zaldivar, J.N.; Gueita-Rodriguez, J.; de Quirós, C.B.B.; Jardón-Huete, A.; Cuesta-Gomez, A. The Impact of a Novel Immersive Virtual Reality Technology Associated with Serious Games in Parkinson’s Disease Patients on Upper Limb Rehabilitation: A Mixed Methods Intervention Study. Sensors 2020, 20, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baqai, A.; Memon, K.; Memon, A.R.; Shah, S.M.Z.A. Interactive Physiotherapy: An Application Based on Virtual Reality and Bio-feedback. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2019, 106, 1719–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, T.A.; Drewelow, G.; Koziol, S.; Rylander, J. A quantitative method for evaluation of 6 degree of freedom virtual reality systems. J. Biomech. 2019, 97, 109379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Bordeleau, M.; Applegate, M. Agreement analysis between Vive and Vicon tracking systems to monitor lumbar postural changes. Ann. Phys. Rehabil Med. 2018, 61, e481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos-Filho, T.; Romero, M.A.; Cardoso, V.; Pomer, A.; Longo, B.; Delisle, D. A Setup for Lower-Limb Post-stroke Rehabilitation Based on Motor Imagery and Motorized Pedal. In IFMBE Proceedings; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1125–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vourvopoulos, A.; Pardo, O.M.; Lefebvre, S.; Neureither, M.; Saldana, D.; Jahng, E.; Liew, S.L. Effects of a brain-computer interface with virtual reality (VR) neurofeedback: A pilot study in chronic stroke patients. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berger, D.J.; D’Avella, A. Towards a Myoelectrically Controlled Virtual Reality Interface for Synergy-Based Stroke Rehabilitation. In Biosystems and Biorobotics; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 965–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahlani, S.S.; Thompson, T.; Parsa, A.D.; Brown, I.; Cirstea, S. ReHabgame: A non-immersive virtual reality rehabilitation system with applications in neuroscience. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karácsony, T.; Hansen, J.P.; Iversen, H.K.; Puthusserypady, S. Brain computer interface for neuro-rehabilitation with deep learning classification and virtual reality feedback. In Proceeding of the 10th Augmented Human International Conference, Reims, France, 11–12 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Juliano, J.M.; Spicer, R.P.; Vourvopoulos, A.; Lefebvre, S.; Jann, K.; Ard, T.; Santarnecchi, E.; Krum, D.M.; Liew, S.-L. Embodiment is related to better performance on a brain–computer interface in immersive virtual reality: A pilot study. Sensors 2020, 20, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lewis, G.N.; Rosie, J.A. Virtual reality games for movement rehabilitation in neurological conditions: How do we meet the needs and expectations of the users. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 1880–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, M.; Kelemen, A.; Sik Lanyi, C. Virtual reality gaming in the rehabilitation of the upper extremities post-stroke. Brain Inj. 2016, 30, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, L.; Jia, Y.; Toro, M.L.; Stoykov, M.E.; Kenyon, R.V.; Kamper, D.G. A pneumatic glove and immersive virtual reality environment for hand rehabilitative training after stroke. IEEE Trans. Neural. Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2010, 18, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J.; Chun, M.H. Combination transcranial direct current stimulation and virtual reality therapy for upper extremity training in patients with subacute stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, M.Y.; Jeon, Y.J.; Kim, S.; Shin, J.H. Virtual Reality Rehabilitation with Functional Electrical Stimulation Improves Upper Extremity Function in Patients With Chronic Stroke: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 1447–1453.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villiger, M.; Liviero, J.; Awai, L.; Stoop, R.; Pyk, P.; Clijsen, R.; Curt, A.; Eng, K.; Bolliger, M. Home-based virtual reality-augmented training improves lower limb muscle strength, balance, and functional mobility following chronic incomplete spinal cord injury. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gervasi, O.; Magni, R.; Zampolini, M. Nu!RehaVR: Virtual reality in neuro tele-rehabilitation of patients with traumatic brain injury and stroke. Virtual. Real. 2010, 14, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.H.; Paik, N.J. Mobile game-based virtual reality program for upper extremity stroke rehabilitation. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 133, 56241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairy, D.; Veras, M.; Archambault, P.; Hernandez, A.; Higgins, J.; Levin, M.F.; Poissant, L.; Raz, A.; Kaizer, F. Maximizing post-stroke upper limb rehabilitation using a novel telerehabilitation interactive virtual reality system in the patient’s home: Study protocol of a randomized clinical trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2016, 47, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. ICF CHECKLIST Version 2.1a, Clinician Form for International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/icfchecklist.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- WHO. Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health ICF Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. How to Use the ICF A Practical Manual for Using the International Classification of Functionining, Disability and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/classifications/drafticfpracticalmanual.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Geertzen, J.H.B.; Rommers, G.M.; Dekker, R. An ICF-based education programme in amputation rehabilitation for medical residents in the Netherlands. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2011, 35, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- VIVE™. VIVE Cosmos Elite Features. Available online: https://www.vive.com/sea/product/vive-cosmos-elite/features/ (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Vive. Vive Support—Planning Your Play Area. Available online: https://www.vive.com/us/support/vive-pro-eye/category_howto/planning-your-play-area.html (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Castaneda, D.; Esparza, A.; Ghamari, M.; Soltanpur, C.; Nazeran, H. A review on wearable photoplethysmography sensors and their potential future applications in health care. Int. J. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 4, 195. [Google Scholar]

- Biocca, F. The Cyborg’s Dilemma: Progressive Embodiment in Virtual Environments. J. Comput. Commun. 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parger, M.; Schmalstieg, D.; Mueller, J.H.; Steinberger, M. Human upper-body inverse kinematics for increased embodiment in consumer-grade virtual reality. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology, Tokyo, Japan, 28 November–1 December 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, M. Biomechatronics. In Biomechatronics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, D.; Dionne, O.; Bouvier-Zappa, S. Animation rigging unity package. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH Conference, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 28 July–1 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- GitHub. Unity-Runtime-Animation-Recorder: Record Animations in Unity Runtime. Available online: https://github.com/newyellow/Unity-Runtime-Animation-Recorder (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoi, G. General Anatomy of the Systems of the Human Body; Universitatii Edition: Craiova, Romania, 2003; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilović, N.; Arsić, A.; Domazet, D.; Mishra, A. Algorithm for adaptive learning process and improving learners’ skills in Java programming language. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2018, 26, 1362–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proyecto 26. Rest Client for Unity. Available online: https://assetstore.unity.com/packages/tools/network/rest-client-for-unity-102501 (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Bahreini, K.; van der Vegt, W.; Westera, W. A fuzzy logic approach to reliable real-time recognition of facial emotions. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 18943–18966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eckman, P.; Friesen, W. Facial Action Coding System: Investigator’s Guide; Consulting Psychologists Press: Sunnyvale, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.; Mehta, S. The clinical development process for a novel preventive vaccine: An overview. J. Postgrad. Med. 2016, 62, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIH Clinical Center. Patient Recruitment—Healthy Volunteers. Available online: https://clinicalcenter.nih.gov/recruit/volunteers.html (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Council for International, Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS); World Health Organization (WHO). International Ethical Guidelines for Health-Related Research Involving Humans Prepared by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) in Collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO), 4th ed.; Council for International, Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS): Geneva, Switzerland; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Grimby, G.; Börjesson, M.; Jonsdottir, I.H.; Schnohr, P.; Thelle, D.S.; Saltin, B. The “Saltin-Grimby Physical Activity Level Scale” and its application to health research. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2015, 25, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, W.C.; Rubens, M.T.; Sabharwal, J.; Gazzaley, A. Deficit in switching between functional brain networks underlies the impact of multitasking on working memory in older adults. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 7212–7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Busman, M. PT Goniometer. Apple App Store. Available online: https://apps.apple.com/us/app/pt-goniometer/id1025114108 (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Nasri, N.; Orts-Escolano, S.; Gomez-Donoso, F.; Cazorla, M. Inferring Static Hand Poses from a Low-Cost Non-Intrusive sEMG Sensor. Sensors 2019, 19, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Slutter, M. Creating a Feedback System with the Myo Armband, for Home Training for Frail Older Adults. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 14 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- HTC Corporation. HTC VIVE Tracker Developer Guidelines Ver. 1.0 Version Control. Available online: https://dl.vive.com/Tracker/Guideline/HTC_Vive_Tracker(2018)_Developer+Guidelines_v1.0.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Umek, A.; Kos, A. Validation of smartphone gyroscopes for mobile biofeedback applications. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2016, 20, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corbetta, D.; Imeri, F.; Gatti, R. Rehabilitation that incorporates virtual reality is more effective than standard rehabilitation for improving walking speed, balance and mobility after stroke: A systematic review. J. Physiother. 2015, 61, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- MyoWare Muscle Sensor—SEN-13723—SparkFun Electronics. Available online: https://www.sparkfun.com/products/13723 (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Cossovich, R. Arduino Tutorial Series: Connecting to Unity | by Rodolfo Cossovich | Interface-Lab | Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/interface-lab/arduino-tutorial-series-connecting-to-unity-eedc48e77087 (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Wodzyński, M.M. Development and Implementation of a Hardware/Software Platform Using Physiological Condition Information as Parameters of a Virtual Reality Environment in Real Time. Master’s Thesis, Warsaw University of Technology, Warsawa, Poland, 31 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

| SpringerLink | PubMed | Elsevier (Scopus) | IEEE Xplore |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1129 | 750 | 564 | 87 |

| Robotics | Virtual Reality | Augmented Reality | Mixed Reality | Reviews/Surveys | General |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 296 | 593 | 17 | 8 | 166 (52/114) | 260 |

| Stroke | Parkinson’s Disease | Brain Trauma | Spinal Cord Trauma |

|---|---|---|---|

| 148 | 16 | 21 | 8 |

| Exercise | Health Condition (s) | Body Functions | Body Structures | Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tutorial—upper limb | ||||

| Shoulder flexion/extension 0°–90°, 90–180° Shoulder abduction/adduction | Stroke, Parkinson’s disease, neuropathies | Mobility of joint, perception | Shoulder region, upper extremity (arm), brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves | Learning and applying knowledge, communication, mobility |

| Arm pushing (downwards) Arm pushing (front) | Stroke, Parkinson’s disease, neuropathies | Mobility of joint, muscle power, perception | Shoulder region, upper extremity (arm, hand), trunk, brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves | Learning and applying knowledge, communication, mobility |

| Forearm extension/flexion Forearm pronation/supination Fist extension Fist adduction (“waving”) | Stroke, Parkinson’s disease, neuropathies | Mobility of joint, perception | Upper extremity (arm, hand), brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves | Learning and applying knowledge, communication, mobility |

| Spinning wheel | Stroke, Parkinson’s disease, neuropathies | Mobility of joint, orientation, perception, balance | Upper extremity (arm, hand), brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves | Learning and applying knowledge, communication, mobility |

| Boxing training (jab punches) | Stroke, Parkinson’s disease (early stages) | Mobility of joint, muscle power, muscle tone, perception, balance, energy and drive functions | Upper extremity (arm, hand), shoulder, brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves | Learning and applying knowledge, communication, mobility |

| Tutorial—lower limb | ||||

| Hip flexion Hip abduction Knee flexion (forward and backward) Ankle flexion/extension | Stroke, Parkinson’s disease, disc herniation | Mobility of joint, perception, balance (if performed while standing) | Pelvis, lower extremity, brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves | Learning and applying knowledge, communication, mobility |

| Exercise | Health Condition (s) | Body Functions | Body Structures | Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carnival games | ||||

| Hit targets Ball directing | Stroke, Parkinson’s disease, neuropathies | Muscle power, orientation, attention, perception | Shoulder region, upper extremity (arm), brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves | Applying knowledge, undertaking simple and multiple tasks, mobility, communication |

| Whack-a-mole | Stroke, Parkinson’s disease, neuropathies | Mobility of joint, movements, orientation, attention, perception | Shoulder region, upper extremity (arm), brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves | Applying knowledge, undertaking simple and multiple tasks, mobility, communication |

| Boxing | ||||

| Guard, multiple, complex hits | Stroke, Parkinson’s disease (early stages), neuropathies | Mobility of joint, muscle power, muscle tone, perception, balance, energy and drive functions | Upper extremity (arm, hand), shoulder, brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves | Applying knowledge, undertaking simple and multiple tasks, mobility, communication |

| Lower body games | ||||

| Football Dancing | Stroke, Parkinson’s disease, disc herniation | Mobility of joint, muscle power, muscle tone, attention, perception, energy and drive, balance, orientation (if performed while standing) | Pelvis, lower extremity, brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves | Applying knowledge, undertaking simple and multiple tasks, mobility, communication |

| User ID | Age | Activity Level | Technological Skills | VR Skills |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| User 1 | 25 | Light activity | Good | Very low |

| User 2 | 29 | Regular activity | Good | Fair |

| User 3 | 27 | Hard activity | Excellent | Excellent |

| User 4 | 55 | Regular activity | Low | Low |

| User 5 | 59 | Inactive | Very low | Very low |

| User 6 | 55 | Light activity | Fair | Low |

| User 7 | 84 | Inactive | Very low | Very low |

| User 8 | 87 | Inactive | Very low | Very low |

| Phase ID | Purpose | Activities | Performance Measurements | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 0 | System presentation and accommodation | - Informed consent - Initial health parameters measured (heart rate, blood pressure) - System presentation (hardware and software) - VR accommodation (if applicable) - User muscular profile calibrated on the Myo gesture control armband - VR system configuration according to the user’s data (if applicable) | - User feedback | One hour |

| Phase 1 | Classical training exercises for both upper and lower limb Goniometer and system’s recorded values comparison | - Fitness bracelet exercising mode started - Upper limb exercises, 5 repetitions/trials with each limb at a time and 5 repetitions with both at the same time:

| - Joint angles (system) for each individual trial - Goniometer angle for first trial - System accuracy—per exercise, per patient, overall - Average joint angle for right/left limb across all 5 trials - Mobility degree (according to mobility classes established in Appendix A) - Average execution times for each exercise | One hour |

| Phase 2 | Gamified training | - Presentation of input for performing in-game actions and accommodation time (a few minutes) for each game - Hit targets: 3 min adaptively, from easy and gradually increasing difficulty levels (medium, difficult) - Ball directing: 3 trials of one minute each, the user must beat their previous record - Whack-a-mole: 3 trials of one minute each with different levels of difficulty (easy, medium, difficult) - Boxing—3 trials of one minute each in different settings (2 in the ring—easy, 1 with the punching bag—medium) - Football—3 trials with 12 shots each (2 from penalty distance, 1 from free kick distance) | - Score according to each game’s logic - Performance classes of each game (according to the classes established in Annex 2) - Hit targets: maximum difficult reached, number of cans hit in each hit, number of tries to complete a level - Ball directing game: number of holes hit - Whack-a-mole: number of moles hit, maximum number of moles that could have been hit, accuracy - Boxing: number of hits with right and left fist; applied force - Football: number of goals, accuracy | 30–45 min |

| Phase 3 | Final feedback | - Feedback collected related to topics such as:

| - User feedback | 15–20 min |

| User ID | Shoulder Flexion | Shoulder Abduction | Elbow Flexion | Elbow Supination | Arm Pushing | Fist Extension | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | Avg. Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | Avg. Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | Avg. Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | Avg. Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | Avg. Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | |

| User 1 | 96.4 | 5 | 60.5 79.5 80 117 118 98 | 82.4 | 5 | 50 61 89 97 59 87 | 123.2 | 5 | 52.5 70.5 69 136 76 82 | 45.4 | 3 | 81 138.5 98 132 128 105 | 60.4 | 5 | 90 81 97 75 107 99 | 46.2 | 3 | 52 74 52 50 44 62 |

| 89.5 | 5 | 83.6 | 5 | 119.6 | 5 | 57.8 | 4 | 59.4 | 4 | 35.6 | 3 | |||||||

| User 2 | 88.8 | 5 | 105.2 | 5 | 151.8 | 5 | 105.8 | 5 | 59.4 | 4 | 63.6 | 4 | ||||||

| 85 | 5 | 103.2 | 5 | 136.4 | 5 | 102.6 | 5 | 49.4 | 4 | 62.8 | 4 | |||||||

| User 3 | 86.6 | 5 | 90.6 | 5 | 115.2 | 5 | 70.8 | 4 | 34 | 3 | 35.8 | 3 | ||||||

| 92.8 | 5 | 88.8 | 5 | 116.4 | 5 | 71.2 | 4 | 54.2 | 4 | 36.2 | 3 | |||||||

| User 4 | 109.4 | 5 | 90.2 | 5 | 99.2 | 4 | 80.2 | 5 | 66.4 | 5 | 67.4 | 4 | ||||||

| 108.6 | 5 | 87.4 | 5 | 94.2 | 4 | 91.4 | 5 | 62.6 | 5 | 67.8 | 4 | |||||||

| User 5 | 94.8 | 5 | 95.2 | 5 | 125.4 | 5 | 99.6 | 5 | 53.4 | 4 | 71.2 | 5 | ||||||

| 98.4 | 5 | 93.4 | 5 | 114 | 5 | 102.4 | 5 | 48.2 | 4 | 52.2 | 4 | |||||||

| User 6 | 87.4 | 5 | 80.8 | 5 | 120.4 | 5 | 86.6 | 5 | 39.6 | 3 | 57 | 4 | ||||||

| 88.6 | 5 | 78 | 4 | 107 | 5 | 82.2 | 5 | 45 | 4 | 48.4 | 3 | |||||||

| Avg. (Right/Left) | 93.9 | 5 | 92.2 | 90.73 | 5 | 73.8 | 122.53 | 4.83 | 81 | 81.4 | 3.67 | 113.7 | 52.2 | 4 | 91.5 | 56.87 | 3.83 | 55.7 |

| 93.81 | 5 | 89.07 | 4.83 | 114.6 | 4.83 | 84.6 | 4.67 | 53.13 | 4.17 | 50.5 | 3.5 | |||||||

| User ID * | Hip Flexion | Hip Abduction | Knee Flexion | Ankle Flexion | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. Angle Right/left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | Avg. Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | Avg. Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | Avg. Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | |

| User 1 User 2 User 3 User 5 User 6 | 88.4 85.6 74 54.6 98.8 99.4 67.4 68.4 86.2 89.4 | 5 5 4 4 5 5 4 4 5 5 | 32.5 70 92 52 84 | 65.4 57.2 53.4 40.6 60.2 72.8 46.8 50.8 67.2 64.2 | 5 5 5 4 5 5 5 5 5 5 | 42.5 109.5 60 45 59 | 109 130.2 70.8 55 122.6 130.6 98.8 107.4 83.4 80.4 | 5 5 4 4 5 5 5 5 4 4 | 37.5 66.5 125 43 106 | 21.4 26.4 34.6 36.6 25.6 25.6 49 31.4 36.2 40.4 | 4 4 4 5 4 4 5 4 5 5 | 69.5 94.5 32 58 62 |

| Avg. (right/left) | 82.96 79.48 | 4.6 4.6 | 66.1 | 58.6 57.12 | 5 4.8 | 63.2 | 96.92 100.72 | 4.6 4.6 | 75.6 | 33.36 32.08 | 4.4 4.4 | 63.2 |

| User ID | Shoulder Flexion | Shoulder Abduction | Elbow Flexion | Elbow Supination/Pronation | Arm Pushing | Fist Extension | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | |

| User 7 User 8 | 46 34 72 76 | 2 2 4 4 | 160 125 | 54 44 79 78 | 3 3 4 4 | 145 165 | 127 136 129 142 | 5 5 5 5 | 252 250 | 72/59 73/44 89/83 90/88 | 4/4 4/3 5/5 5/5 | 165 160 | 25 24 40 51 | 2 2 3 4 | 195 175 | 61 73 55 52 | 4 5 4 4 | 200 145 |

| User ID | Hip Flexion | Knee Flexion | Ankle Flexion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. Angle Right/left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | Avg. Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | Avg. Angle Right/Left | ROM Right/Left | t(s) Right + Left | |

| User 7 User 8 | 47 52 71 72 | 4 4 4 4 | 160 125 | 10 15 30 30 | 1 2 3 3 | 210 125 | 16 22 25 21 | 3 4 4 4 | 120 155 |

| User ID | Shoulder Flexion | Shoulder Abduction | Elbow Flexion | Elbow Supination | Arm Pushing | Fist Extension | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angle (gon.) | Angle(sys.) | Acc. (%) | Angle (gon.) | Angle (sys.) | Acc. (%) | Angle (gon.) | Angle (sys.) | Acc. (%) | Angle (gon.) | Angle (sys.) | Acc. (%) | Angle (gon.) | Angle(sys.) | Acc. (%) | Angle (gon.) | Angle(sys.) | Acc. (%) | |

| User 1 | 86 | 94 | 90.7 | 83 | 85 | 97.6 | 130 | 123 | 94.61 | 37 | 43 | 83.78 | 55 | 57 | 96.36 | 57 | 57 | 100 |

| User 2 | 89 | 92 | 96.63 | 92 | 95 | 96.73 | 135 | 141 | 95.55 | 84 | 89 | 94.04 | 60 | 59 | 98.33 | 69 | 62 | 89.85 |

| User 3 | 86 | 86 | 100 | 88 | 91 | 96.59 | 115 | 113 | 98.26 | 58 | 61 | 94.82 | 46 | 47 | 97.82 | 30 | 32 | 93.33 |

| User 4 | 98 | 105 | 92.86 | 90 | 92 | 97.77 | 118 | 114 | 96.61 | 75 | 74 | 98.67 | 70 | 65 | 92.85 | 60 | 59 | 98.33 |

| User 5 | 92 | 96 | 95.66 | 81 | 88 | 91.35 | 137 | 130 | 94.89 | 81 | 83 | 97.53 | 68 | 62 | 91.17 | 61 | 54 | 88.52 |

| User 6 | 84 | 85 | 98.89 | 81 | 80 | 98.76 | 113 | 116 | 97.34 | 83 | 82 | 98.79 | 34 | 34 | 100 | 54 | 55 | 98.14 |

| Avg. Acc. (%) | 95.79 | 96.46 | 96.21 | 94.60 | 96.08 | 94.70 | ||||||||||||

| User ID * | Hip Flexion | Hip Abduction | Knee Flexion | Ankle Flexion | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angle (gon.) | Angle (sys.) | Acc. (%) | Angle (gon.) | Angle (sys.) | Acc. (%) | Angle (gon.) | Angle (sys.) | Acc. (%) | Angle (gon.) | Angle (sys.) | Acc. (%) | |

| User 1 | 80 | 81 | 98.75 | 60 | 58 | 96.66 | 102 | 110 | 92.15 | 35 | 31 | 88.57 |

| User 2 | 72 | 73 | 98.61 | 40 | 44 | 90 | 66 | 64 | 96.96 | 32 | 31 | 96.87 |

| User 3 | 92 | 90 | 97.83 | 60 | 62 | 96.66 | 125 | 128 | 97.6 | 32 | 31 | 96.87 |

| User 5 | 67 | 68 | 98.5 | 47 | 52 | 89.36 | 80 | 90 | 87.5 | 33 | 35 | 93.94 |

| User 6 | 82 | 82 | 100 | 54 | 54 | 100 | 80 | 78 | 97.5 | 25 | 26 | 96 |

| Avg. Acc. (%) | 98.74 | 94.54 | 94.34 | 94.45 | ||||||||

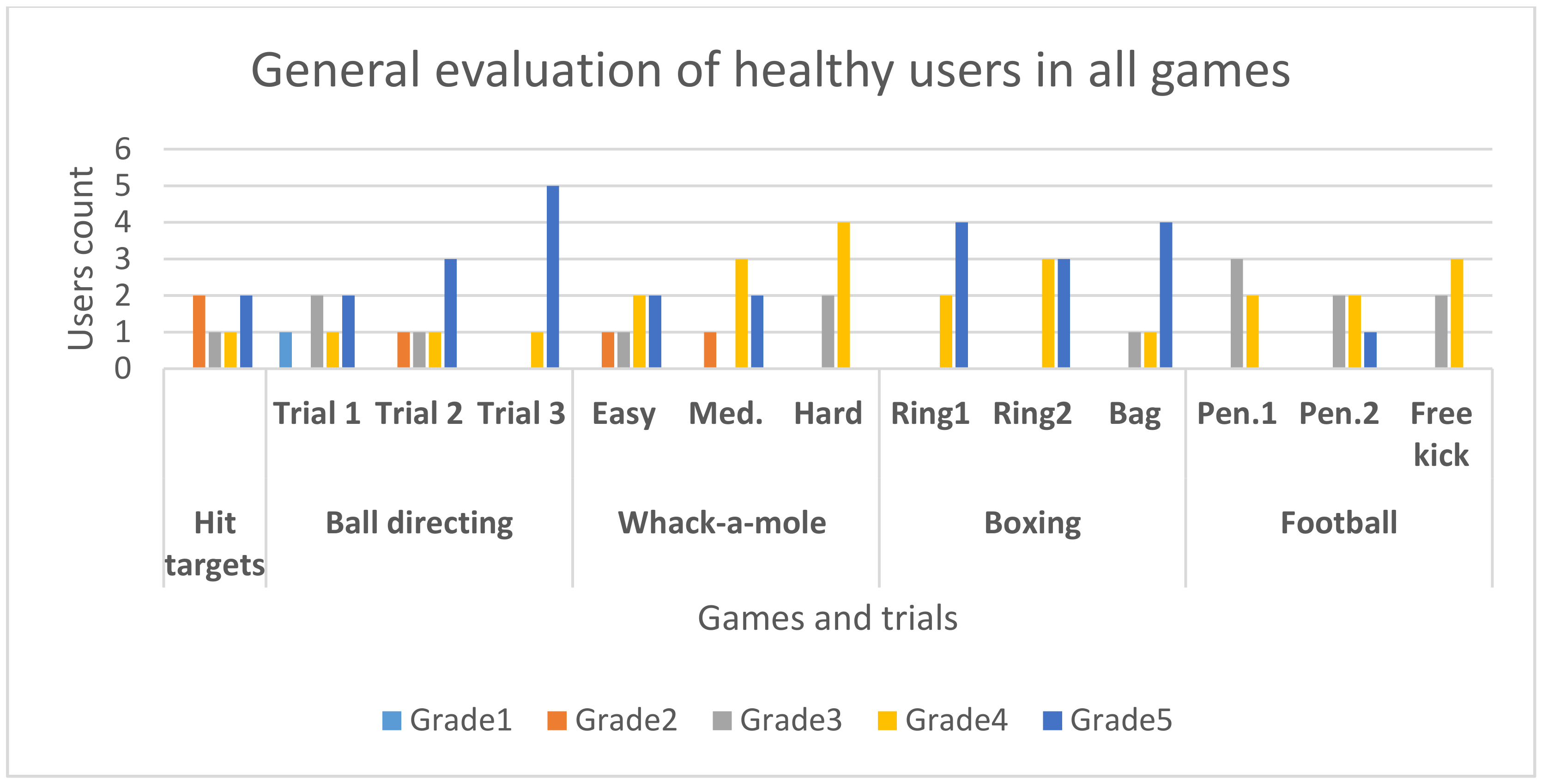

| User ID | Hit Targets | Ball Directing | Whack-A-Mole | Boxing | Football | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Min Adaptively | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 3 | Easy | Med. | Hard | Ring1 | Ring2 | Bag | Pen.1 | Pen.2 | Free Kick | |

| User 1 | 3 (reached medium level) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| User 2 | 4 (almost completed medium) | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| User 3 | 5 (reached and completed difficult) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| User 4 * | 2 (2 easy trials started but not completed) | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | - | - | - |

| User 5 | 2 (2 easy trials started but not completed) | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| User 6 | 5 (completed multiple difficult levels) | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Avg. | 3.5 | 4 | 4.83 | 3.83 | 4 | 3.67 | 4.67 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 3.6 | |

| User ID | Heart Rate | Effort Levels (% of Entire Training Session) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Value | Max. Value | Medium Value | Relaxed | Low | Intense | |

| User 1 | 100 | 134 | 105 | 19.85% | 58.78% | 21.37% |

| User 2 | 66 | 118 | 85 | 90.63% | 9.37% | 0.00% |

| User 3 | 84 | 112 | 92 | 70.59% | 22.35% | 7.06% |

| User 4 * | 83 | 100 | 83 | 98.96% | 1.04% | 0.00% |

| User 5 | 72 | 121 | 86 | 72.39% | 25.77% | 1.84% |

| User 6 | 82 | 121 | 97 | 38.75% | 55.81% | 5.44% |

| User 7 * | 68 | 81 | 70 | 100% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| User 8 * | 72 | 95 | 66 | 100% | 0.00% | 0.00& |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stanica, I.-C.; Moldoveanu, F.; Portelli, G.-P.; Dascalu, M.-I.; Moldoveanu, A.; Ristea, M.G. Flexible Virtual Reality System for Neurorehabilitation and Quality of Life Improvement. Sensors 2020, 20, 6045. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20216045

Stanica I-C, Moldoveanu F, Portelli G-P, Dascalu M-I, Moldoveanu A, Ristea MG. Flexible Virtual Reality System for Neurorehabilitation and Quality of Life Improvement. Sensors. 2020; 20(21):6045. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20216045

Chicago/Turabian StyleStanica, Iulia-Cristina, Florica Moldoveanu, Giovanni-Paul Portelli, Maria-Iuliana Dascalu, Alin Moldoveanu, and Mariana Georgiana Ristea. 2020. "Flexible Virtual Reality System for Neurorehabilitation and Quality of Life Improvement" Sensors 20, no. 21: 6045. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20216045

APA StyleStanica, I.-C., Moldoveanu, F., Portelli, G.-P., Dascalu, M.-I., Moldoveanu, A., & Ristea, M. G. (2020). Flexible Virtual Reality System for Neurorehabilitation and Quality of Life Improvement. Sensors, 20(21), 6045. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20216045