Blockchain for Electronic Voting System—Review and Open Research Challenges

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Core Components of Blockchain Architecture

- Node: Users or computers in blockchain layout (every device has a different copy of a complete ledger from the blockchain);

- Transaction: It is the blockchain system’s smallest building block (records and details), which blockchain uses;

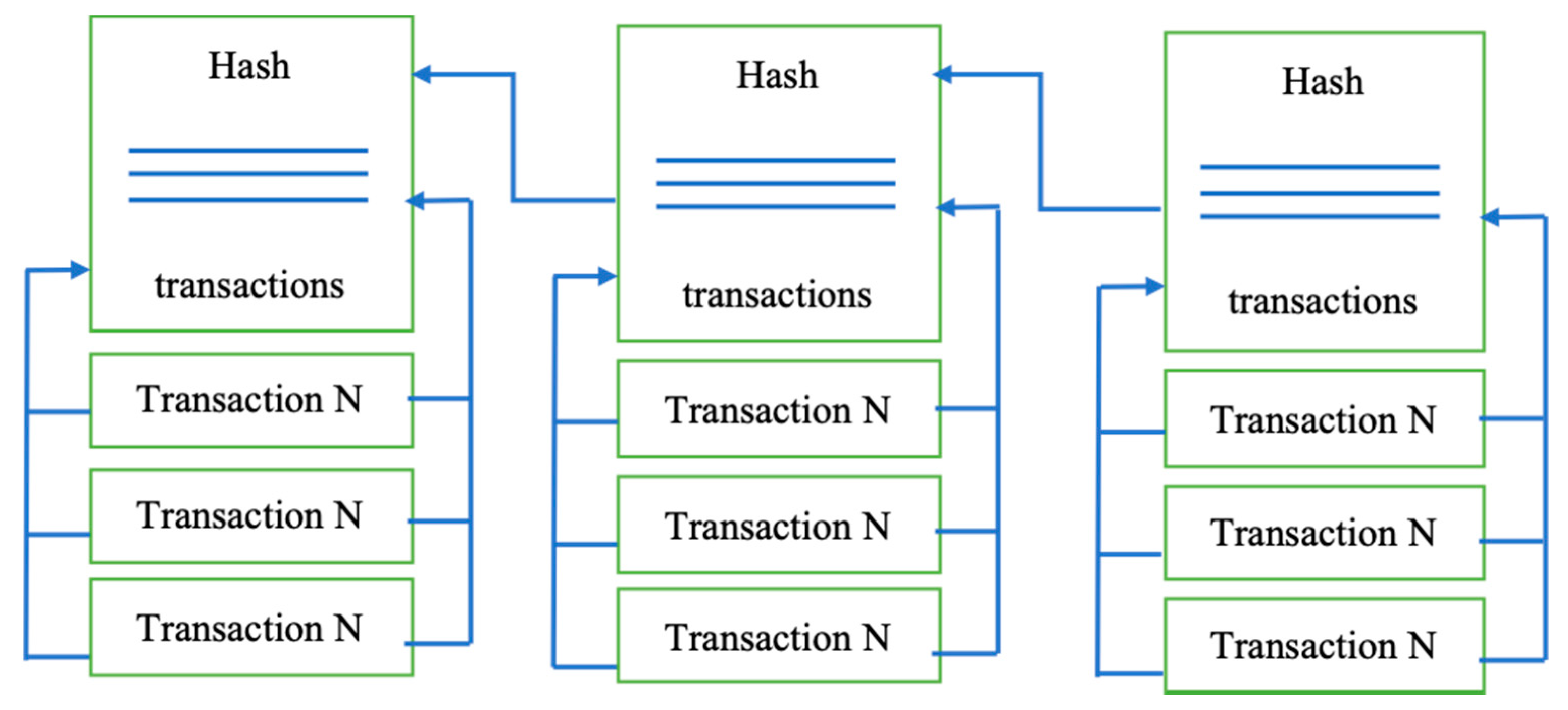

- Block: A block is a collection of data structures used to process transactions over the network distributed to all nodes.

- Chain: A series of blocks in a particular order;

- Miners: Correspondent nodes to validate the transaction and add that block into the blockchain system;

- Consensus: A collection of commands and organizations to carry out blockchain processes.

2.2. Critical Characteristics of Blockchain Architecture

- Cryptography: Blockchain transactions are authenticated and accurate because of computations and cryptographic evidence between the parties involved;

- Immutability: Any blockchain documents cannot be changed or deleted;

- Provenance: It refers to the fact that every transaction can be tracked in the blockchain ledger;

- Decentralization: The entire distributed database may be accessible by all members of the blockchain network. A consensus algorithm allows control of the system, as shown in the core process;

- Anonymity: A blockchain network participant has generated an address rather than a user identification. It maintains anonymity, especially in a blockchain public system;

- Transparency: It means being unable to manipulate the blockchain network. It does not happen as it takes immense computational resources to erase the blockchain network.

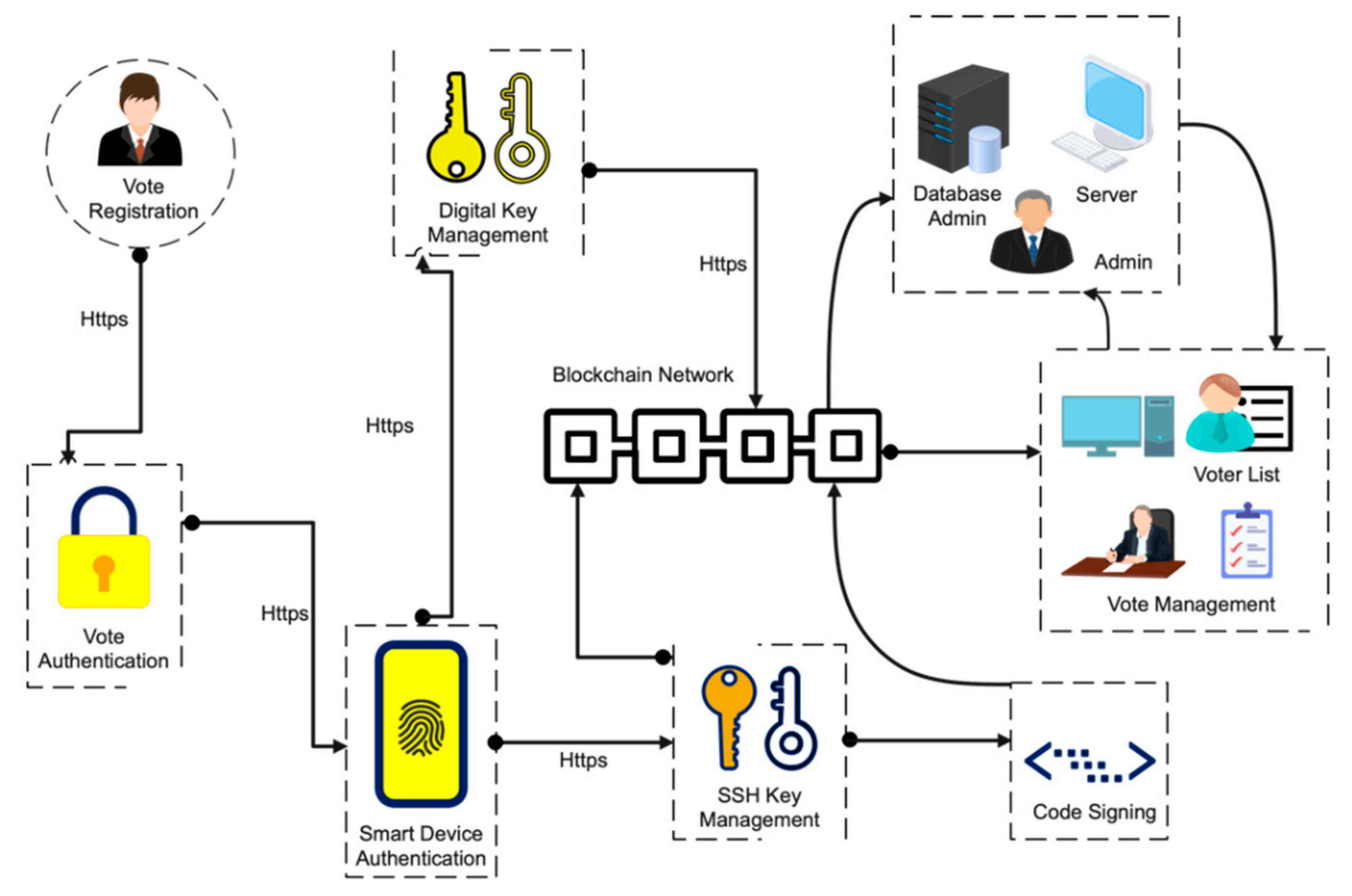

3. How Blockchain Can Transform the Electronic Voting System

4. Problems and Solutions of Developing Online Voting Systems

- Eligibility: Only legitimate voters should be able to take part in voting;

- Unreusability: Each voter can vote only once;

- Privacy: No one except the voter can obtain information about the voter’s choice;

- Fairness: No one can obtain intermediate voting results;

- Soundness: Invalid ballots should be detected and not taken into account during tallying;

- Completeness: All valid ballots should be tallied correctly.

4.1. Eligibility

4.2. Unreusability

4.3. Privacy

4.4. Fairness

4.5. Soundness and Completeness

5. Security Requirements for Voting System

5.1. Anonymity

5.2. Auditability and Accuracy

5.3. Democracy/Singularity

5.4. Vote Privacy

5.5. Robustness and Integrity

5.6. Lack of Evidence

5.7. Transparency and Fairness

5.8. Availability and Mobility

5.9. Verifiable Participation/Authenticity

5.10. Accessibility and Reassurance

5.11. Recoverability and Identification

5.12. Voters Verifiability

6. Electronic Voting on Blockchain

7. Current Blockchain-Based Electronic Voting Systems

7.1. Follow My Vote

7.2. Voatz

7.3. Polyas

7.4. Luxoft

7.5. Polys

7.6. Agora

8. Related Literature Review

9. Discussion and Future Work

9.1. Scalability and Processing Overheads

9.2. User Identity

9.3. Transactional Privacy

9.4. Energy Efficiency

9.5. Immatureness

9.6. Acceptableness

9.7. Political Leaders’ Resistance

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Q. An E-voting Protocol Based on Blockchain. IACR Cryptol. Eprint Arch. 2017, 2017, 1043. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, B.; Crowcroft, J. Trustworthy Electronic Voting Using Adjusted Blockchain Technology. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 24477–24488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racsko, P. Blockchain and Democracy. Soc. Econ. 2019, 41, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaga, D.; Mell, P.; Roby, N.; Scarfone, K. Blockchain technology overview. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.11078. [Google Scholar]

- The Economist. EIU Democracy Index. 2017. Available online: https://infographics.economist.com/2018/DemocracyIndex/ (accessed on 18 January 2020).

- Cullen, R.; Houghton, C. Democracy online: An assessment of New Zealand government web sites. Gov. Inf. Q. 2000, 17, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinckus, C. The good, the bad and the ugly: An overview of the sustainability of blockchain technology. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 69, 101614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Zheng, D.; Guo, R.; Jing, C.; Hu, C. An Anti-Quantum E-Voting Protocol in Blockchain with Audit Function. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 115304–115316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Ochoa, J.; Faika, T.; Mantooth, A.; Di, J.; Li, Q.; Lee, Y. An overview of cyber-physical security of battery management systems and adoption of blockchain technology. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, L.; Kim, D.-H. Design and implementation of an integrated iot blockchain platform for sensing data integrity. Sensors 2019, 19, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chang, V.; Baudier, P.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Arami, M. How Blockchain can impact financial services–The overview, challenges and recommendations from expert interviewees. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 158, 120166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Sun, J.; He, Y.; Pang, D.; Lu, N. Large-scale election based on blockchain. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 129, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ometov, A.; Bardinova, Y.; Afanasyeva, A.; Masek, P.; Zhidanov, K.; Vanurin, S.; Sayfullin, M.; Shubina, V.; Komarov, M.; Bezzateev, S. An Overview on Blockchain for Smartphones: State-of-the-Art, Consensus, Implementation, Challenges and Future Trends. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 103994–104015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakak, S.; Khan, W.Z.; Gilkar, G.A.; Imran, M.; Guizani, N. Securing smart cities through blockchain technology: Architecture, requirements, and challenges. IEEE Netw. 2020, 34, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çabuk, U.C.; Adiguzel, E.; Karaarslan, E. A survey on feasibility and suitability of blockchain techniques for the e-voting systems. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.07175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, N. Formalizing and securing relationships on public networks. First Monday 1997, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, G. Ethereum: A secure decentralised generalised transaction ledger. Ethereum Proj. Yellow Pap. 2014, 151, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W.; Zhu, H.; Tan, J.; Zhao, Y.; Da Xu, L.; Guo, K. A novel service level agreement model using blockchain and smart contract for cloud manufacturing in industry 4.0. Enterp. Inf.Syst. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. Available online: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf. (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Garg, K.; Saraswat, P.; Bisht, S.; Aggarwal, S.K.; Kothuri, S.K.; Gupta, S. A Comparitive Analysis on E-Voting System Using Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Internet of Things: Smart Innovation and Usages (IoT-SIU), Ghaziabad, India, 18–19 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kamil, S.; Ayob, M.; Sheikhabdullah, S.N.H.; Ahmad, Z. Challenges in multi-layer data security for video steganography revisited. Asia-Pacific J. Inf. Technol. Multimed 2018, 7, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffal, R.; Mohd, B.J.; Al-Shayeji, M. An analysis and evaluation of lightweight hash functions for blockchain-based IoT devices. Clust. Comput. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofer, M.; Gomber, P.; Hinz, O.; Schiereck, D. Blockchain. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2017, 59, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Peng, M.; Wang, W.; Jin, Z.; Su, Y.; Chen, H. Secure and efficient data storage and sharing scheme for blockchain—Based mobile—Edge computing. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.; Liskov, B. Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance. Available online: https://www.usenix.org/legacy/publications/library/proceedings/osdi99/full_papers/castro/castro_html/castro.html. (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Laurie, B.; Clayton, R. Proof-of-Work Proves Not to Work. Available online: http://www.infosecon.net/workshop/downloads/2004/pdf/clayton.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Prashar, D.; Jha, N.; Jha, S.; Joshi, G.; Seo, C. Integrating IOT and blockchain for ensuring road safety: An unconventional approach. Sensors 2020, 20, 3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froomkin, A.M. Anonymity and Its Enmities. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2715621 (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Pawlak, M.; Poniszewska-Marańda, A. Implementation of Auditable Blockchain Voting System with Hyperledger Fabric. In International Conference on Computational Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jalal, I.; Shukur, Z.; Bakar, K.A.A. A Study on Public Blockchain Consensus Algorithms: A Systematic Literature Review. Preprints 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, B.K.; Jena, D.; Panda, S.S.; Sobhanayak, S. Blockchain technology: A survey on applications and security privacy challenges. Internet Things 2019, 8, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Xie, S.; Dai, H.-N.; Chen, W.; Chen, X.; Weng, J.; Imran, M. An overview on smart contracts: Challenges, advances and platforms. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 105, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliveira, M.T.; Carrara, G.R.; Fernandes, N.C.; Albuquerque, C.; Carrano, R.C.; Medeiros, D.S.V.; Mattos, D. Towards a performance evaluation of private blockchain frameworks using a realistic workload. In Proceedings of the 2019 22nd Conference on Innovation in Clouds, Internet and Networks and Workshops (ICIN), Paris, France, 19–21 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, H.A.; Mansor, Z.; Shukur, Z. Comprehensive Survey And Research Directions On Blockchain Iot Access Control. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Applications. 2021, 12, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Wang, X.A.; Wang, W.; Wang, H. Survey on Blockchain-Based Electronic Voting. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Networking and Collaborative Systems, Oita, Japan, 5–7 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Imperial, M. The Democracy to Come? An Enquiry into the Vision of Blockchain-Powered E-Voting Start-Ups. Front. Blockchain 2021, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.E. The effects of eligibility restrictions and party activity on absentee voting and overall turnout. Am. J. Political Sci. 1996, 40, 498–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, R. Voting eligibility: Strasbourg’s timidity. In the UK and European Human Rights: A Strained Relationship; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2015; pp. 165–191. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Chen, L.; Rong, C.; Liang, K.; Zheng, X.; Yu, J. Security Analysis and Improvement of a Redactable Consortium Blockchain for Industrial Internet-of-Things. Comput. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, H.; Alazab, M.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Han, Z.; Su, C. Blockchain-Based Reliable and Efficient Certificateless Signature for IIoT Devices. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, A.; Okamoto, T.; Ohta, K. A practical secret voting scheme for large scale elections. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on the Theory and Application of Cryptographic Techniques, Queensland, Australia, 13–16 December 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Haenni, R.; Spycher, O. Secure Internet Voting on Limited Devices with Anonymized DSA Public Keys. In Proceedings of the 2011 Conference on Electronic Voting Technology/Workshop on Trustworthy Elections, Francisco, CA, USA, 8–9 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, S.; Xiang, Y. Anonymous Blockchain-based System for Consortium. ACM Trans. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2021, 12, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, C. A Fully Homomorphic Encryption Scheme; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2009; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Hussien, H.; Aboelnaga, H. Design of a secured e-voting system. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Computer Applications Technology (ICCAT), Sousse, Tunisia, 20–22 January 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Goldreich, O.; Oren, Y. Definitions and properties of zero-knowledge proof systems. J. Cryptol. 1994, 7, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Faveri, C.; Moreira, A.; Araújo, J.; Amaral, V. Towards security modeling of e-voting systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 24th International Requirements Engineering Conference Workshops (REW), Beijing, China, 12–16 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S.; Chu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Nadarajah, S. Blockchain and Cryptocurrencies. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, D.B.; Chaudhary, V.; Doku, R. Blockchain technology: Emerging applications and use cases for secure and trustworthy smart systems. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2021, 1, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, H.-T. A secure electronic voting protocol for general elections. Comput. Secur. 2004, 23, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyal, A.A.; Junejo, A.Z.; Zawish, M.; Ahmed, K.; Khalil, A.; Soursou, G. Applications of blockchain technology in medicine and healthcare: Challenges and future perspectives. Cryptography 2019, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, X.; Zhou, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, G. A Blockchain Voting System Based on the Feedback Mechanism and Wilson Score. Information 2020, 11, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, C.; Wang, S. An improved FOO voting scheme using blockchain. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2020, 19, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadia, K.; Masuduzzaman, M.; Paul, R.K.; Islam, A. Blockchain-based secure e-voting with the assistance of smart contract. In IC-BCT 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Adeshina, S.A.; Ojo, A. Maintaining voting integrity using Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2019 15th International Conference on Electronics, Computer and Computation (ICECCO), Abuja, Nigeria, 10–12 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Augoye, V.; Tomlinson, A. Analysis of Electronic Voting Schemes in the Real World. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1013&context=ukais2018 (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Singh, N.; Vardhan, M. Multi-objective optimization of block size based on CPU power and network bandwidth for blockchain applications. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Microelectronics, Computing and Communication Systems, Ranchi, India, 11–12 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, P.; Wang, D.; Zhao, Y.; Tyagi, S.K.S.; Kumar, N. Blockchain data-based cloud data integrity protection mechanism. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 102, 902–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; He, D.; Zeadally, S.; Khan, M.K.; Kumar, N. A survey on privacy protection in blockchain system. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2019, 126, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poniszewska-Marańda, A.; Pawlak, M.; Guziur, J. Auditable blockchain voting system-the blockchain technology toward the electronic voting process. Int. J. Web Grid Serv. 2020, 16, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okediran, O.O.; Sijuade, A.A.; Wahab, W.B. Secure Electronic Voting Using a Hybrid Cryptosystem and Steganography. J. Adv. Math. Comput. Sci. 2019, 34, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafar, U.; Aziz, M.J.A. A State of the Art Survey and Research Directions on Blockchain Based Electronic Voting System. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Cyber Security, Penang, Malaysia, 8–9 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dagher, G.G.; Marella, P.B.; Milojkovic, M.; Mohler, J. Broncovote: Secure Voting System Using Ethereum’s Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy, Funchal, Madeira, Portugal, 22–24 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sree, T.U.; Yerukala, N.; Tentu, A.N.; Rao, A.A. Secret Sharing Scheme Using Identity Based Signatures. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Communication Technologies (ICECCT), Tamil Nadu, India, 20–22 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, M.; Smyth, B. Exploiting re-voting in the Helios election system. Inf. Process. Lett. 2019, 143, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yavuz, E.; Koç, A.K.; Çabuk, U.C.; Dalkılıç, G. Towards secure e-voting using ethereum blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2018 6th International Symposium on Digital Forensic and Security (ISDFS), Antalya, Turkey, 22–25 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hanifatunnisa, R.; Rahardjo, B. Blockchain based e-voting recording system design. In Proceedings of the 2017 11th International Conference on Telecommunication Systems Services and Applications (TSSA), Bali, Indonesia, 26–27 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick, F.S.; Gioulis, A.; Akram, R.N.; Markantonakis, K. E-voting with blockchain: An e-voting protocol with decentralisation and voter privacy. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things (iThings) and IEEE Green Computing and Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData), Halifax, NS, Canada, 30 July–3 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vote, F.M. The Secure Mobile Voting Platform Of The Future—Follow My Vote. 2020. Available online: https://followmyvote.com/ (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Voatz. Voatz—Voting Redefined ®®. 2020. Available online: https://voatz.com (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Polyas. Polyas. 2015. Available online: https://www.polyas.com (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Luxoft. Luxoft. Available online: https://www.luxoft.com/ (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Sayyad, S.F.; Pawar, M.; Patil, A.; Pathare, V.; Poduval, P.; Sayyad, S.; Pawar, M.; Patil, A.; Pathare, V.; Poduval, P. Features of Blockchain Voting: A Survey. Int. J. 2019, 5, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Polys. Polys—Online Voting System. 2020. Available online: https://polys.me/ (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Agora. Agora. 2020. Available online: https://www.agora.vote (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- McCorry, P.; Shahandashti, S.F.; Hao, F. A smart contract for boardroom voting with maximum voter privacy. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security, Sliema, Malta, 3–7 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Xiong, H. Chaintegrity: Blockchain-enabled large-scale e-voting system with robustness and universal verifiability. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2019, 19, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaieb, M.; Koscina, M.; Yousfi, S.; Lafourcade, P.; Robbana, R. DABSTERS: Distributed Authorities Using Blind Signature to Effect Robust Security in E-Voting. Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02145809/document (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Woda, M.; Huzaini, Z. A Proposal to Use Elliptical Curves to Secure the Block in E-voting System Based on Blockchain Mechanism. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Dependability and Complex Systems, Wrocław, Poland, 28 June–2 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hjálmarsson, F.Þ.; Hreiðarsson, G.K.; Hamdaqa, M.; Hjálmtýsson, G. Blockchain-based e-voting system. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 11th International Conference on Cloud Computing (CLOUD), San Francisco, CA, USA, 2–7 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, W.J.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Hsueh, C.W.; Wu, J.L. Date: A decentralized, anonymous, and transparent e-voting system. In Proceedings of the 2018 1st IEEE International Conference on Hot Information-Centric Networking (HotICN), Shenzhen, China, 15–17 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Caramés, T.M.; Fraga-Lamas, P. Towards Post-Quantum Blockchain: A Review on Blockchain Cryptography Resistant to Quantum Computing Attacks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 21091–21116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H. Securing e-voting based on blockchain in P2P network. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2019, 2019, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torra, V. Random dictatorship for privacy-preserving social choice. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2019, 19, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alaya, B.; Laouamer, L.; Msilini, N. Homomorphic encryption systems statement: Trends and challenges. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2020, 36, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.M.; Arshad, J.; Khan, M.M. Investigating performance constraints for blockchain based secure e-voting system. Future Gener. Comput.Syst. 2020, 105, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.-G.; Moon, S.-J.; Jang, J.-W. A Scalable Implementation of Anonymous Voting over Ethereum Blockchain. Sensors 2021, 21, 3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlak, M.; Poniszewska-Marańda, A.; Kryvinska, N. Towards the intelligent agents for blockchain e-voting system. Procedia Comput.Sci. 2018, 141, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, A.T.A.; Zakaria, M.S. Method for designing scalable microservice-based application systematically: A case study. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2018, 9, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, I.; Alharbi, F.; Bellaj, B.; Margaria, T.; Crespi, N.; Qureshi, K. Health-ID: A Blockchain-Based Decentralized Identity Management for Remote Healthcare. Healthcare 2021, 9, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabe, J.B.; Canovas, J.L.; Hernandez-Ramos, J.L.; Moreno, R.T.; Skarmeta, A. Privacy-preserving solutions for blockchain: Review and challenges. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 164908–164940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, T. Efficient, coercion-free and universally verifiable blockchain-based voting. Comput. Netw. 2020, 174, 107234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, I.; Shukur, Z.; Bakar, K.A.B.A. Validators Performance Efficiency Consensus (VPEC): A Public Blockchain. Test Eng. Manag. 2020, 83, 17530–17539. [Google Scholar]

- Saheb, T.; Mamaghani, F.H. Exploring the barriers and organizational values of blockchain adoption in the banking industry. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2021, 32, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gou, G.; Liu, C.; Cui, M.; Li, Z.; Xiong, G. Survey of security supervision on blockchain from the perspective of technology. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2021, 60, 102859. [Google Scholar]

- Kshetri, N.; Voas, J. Blockchain-enabled e-voting. IEEE Softw. 2018, 35, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krishnan, A. Blockchain Empowers Social Resistance and Terrorism through Decentralized Autonomous Organizations. J. Strateg. Secur. 2020, 13, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Online Voting Platforms | Framework | Language | Cryptographic Algorithm | Consensus Protocol | Main Features (Online Blockchain Voting System) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Audit | Anonymity | Verifiability by Voter | Integrity | Accessibility | Scalability | Accuracy/Correctness | Affordability | |||||

| Follow My Vote | Bitcoin | C++/Python | ECC | PoW | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Voatz | Hyperledger Fabric | Go/JavaScript | AES/GCM | PBFT | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Polyas | Private/local Blockchains | NP | ECC | PET | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ | NA |

| Luxoft | Hyperledger Fabric | Go/JavaScript | ECC/ElGamal | PBFT | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Polys | Ethereum | Solidity | Shamir’s Secret Sharing | PoW | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Agora | Bitcoin | Python | ElGamal | BFT-r | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Framework | Year Release | Generation Time | Hash Rate | Transactions Per Sec | Cryptographic Algorithm | Mining Difficulty | Power Consumption | Reward/Block | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bitcoin | 2008 | 9.7 min | 899.624 Th/s | 4.6 max 7 | ECDSA | High (around 165,496,835,118) | Very High | 25 BTC | Very Low |

| Ethereum | 2015 | 10 to 19 s | 168.59 Th/s | 15 | ECDSA | High (around 10,382,102) | High | 5 ether | Low |

| Hyperledger Fabric | 2015 | 10 ms | NA | 3500 | ECC | No mining required | Very Low | No built-in cryptocurrency | Good |

| Litecoin | 2011 | 2.5 min | 1.307 Th/s | 56 | Scrypt | Low 55,067 | Moderate | 25 LTC | Moderate |

| Ripple | 2012 | 3.5 s | NA | 1500 | RPCA | No mining required | Very Low | Base Fee | Good |

| Dogecoin | 2013 | 1 min | 1.4 Th/s | 33 | Scrypt | Low 21,462 | Low | 10,000 Doge | Low |

| Peercoin | 2012 | 10 min | 693.098 Th/s | 8 | Hybrid | Moderate (476,560,083) | Low | 67.12 PPC | Low |

| Authors | Voting Scheme | BC Type | Consensus Algorithm | Framework | Cryptographic Algorithm | Hashing Algorithm | Counting Method | Security Requirements (Measuring on a Large Scale) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anonymity | Audit | Accuracy/Correctness | Accessibility | Integrity | Scalability | Affordability | Verifiability by Voter | ||||||||

| Shahzad and Crowcroft [2] | BSJC | Private | PoW | Bitcoin | Not specified | SHA-256 | 3rd Party | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ | ✘ |

| Gao, Zheng [8] | Anti-Quantum | Public | PBFT | Bitcoin | Certificateless Traceable Ring Signature, Code-Based, ECC | Double SHA-256 | Self-tally | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ | ✘ |

| McCorry, Shahandashti [76] | OVN | Public | 2 Round-zero Knowledge Proof | Ethereum | ECC | Not specified | Self-tally | ✓ | ✘ | ✘ | ✓ | ✘ | ✘ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Lai, Hsieh [81] | DATE | Public | PoW | Ethereum | Ring Signature, ECC, Diffie-Hellman | SHA-3 | Self-tally | ✓ | ✘ | ✘ | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Yi [83] | BES | Public | PoW | Bitcoin | ECC | SHA-256 | NA | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ | ✘ | ✘ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Khan, K.M. [86] | BEA | Private/Public | PoW | Multichain | Not specified | Not specified | NA | ✘ | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jafar, U.; Aziz, M.J.A.; Shukur, Z. Blockchain for Electronic Voting System—Review and Open Research Challenges. Sensors 2021, 21, 5874. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21175874

Jafar U, Aziz MJA, Shukur Z. Blockchain for Electronic Voting System—Review and Open Research Challenges. Sensors. 2021; 21(17):5874. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21175874

Chicago/Turabian StyleJafar, Uzma, Mohd Juzaiddin Ab Aziz, and Zarina Shukur. 2021. "Blockchain for Electronic Voting System—Review and Open Research Challenges" Sensors 21, no. 17: 5874. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21175874

APA StyleJafar, U., Aziz, M. J. A., & Shukur, Z. (2021). Blockchain for Electronic Voting System—Review and Open Research Challenges. Sensors, 21(17), 5874. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21175874