Accuracy of a New Pulse Oximetry in Detection of Arterial Oxygen Saturation and Heart Rate Measurements: The SOMBRERO Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

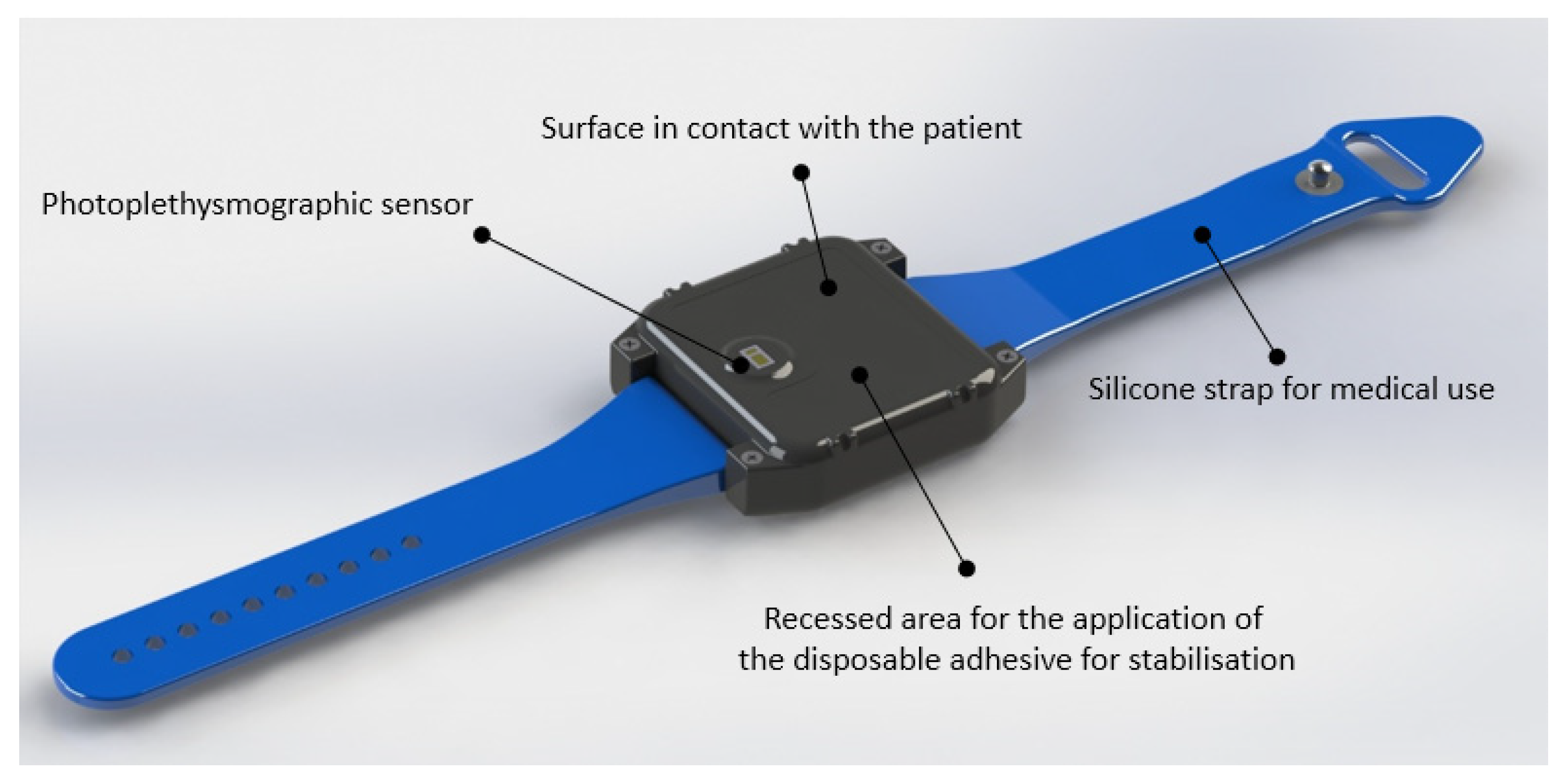

2.2. Materials

- From the signals recorded with the triaxial accelerometric sensor, the jolt (i.e., the derivative in time of acceleration) is calculated as shown in the following equation:where j[t] is the instantaneous jolt value at the time t and x, y, and z are the instantaneous values of the tri-axial acceleration (arbitrary units) detected from the accelerometer sensor at time t and t − 1.

- The time intervals relating to an absence of movement are selected by applying an experimentally determined threshold (threshold value = 18 arbitrary units) on the absolute value of jolt.

- By selecting the red and infrared (IR) signals within the time intervals related to the quiet state of the subject, appropriate bandpass filtering (digital ant causal finite impulse response (FIR) filter of 50th order, bandwidth from 0.5 Hz to 3 Hz) is applied to extract a relevant section of signal that allows to calculate your heart rate.

- From the same raw signals, the following components are extracted:

- RED_DC = continuous part of the red signal (mean value calculated from the epoch of red signal);

- RED_AC = alternating part of the red signal (root mean square value from the epoch of red signal filtered as in point 3);

- IR_DC = continuous part of the infrared signal (mean value from the epoch of IR signal);

- IR_AC = alternating part of the infrared signal (root mean square value calculated from the epoch of IR signal as in point 3);

- From these parameters we calculate the value of the gamma parameter with the equation shown below:

- From the value of we calculate the SpO2 using the following equation:where a, b and c are experimentally calculated and constant parameters for each subject analyzed (a = −44.6, b = 5.9; c = 108.1).

2.3. Participants

2.4. Definition of Valid Measurement

- Signal compliant with quality control for both the reference and BrOxy M;

- No movement above the predefined threshold for both the reference and BrOxy M.

- Starting from the signals, through appropriate band-pass filters, the following components are calculated as follows:

- RED_DC = continuous part of the red signal;

- RED_AC = alternating part of the red signal;

- IR_DC = continuous part of the infrared signal;

- IR_AC = alternating part of the infrared signal;

- Average values of RED_DC and IR_DC have to be in the expected range, determined empirically;

- If the previous point occurs, peak-peak amplitude values of RED_AC and IR_AC have to be in the empirically determined acceptability range;

- If the previous condition is verified, the correlation coefficient calculated between IR_AC and RED_AC has to be higher than the empirically determined threshold.

- Control of the amplitude of photoplethysmographic signals: the amplitude of the alternating component of red and infrared signals (obtained by filtering signals with an anti-causal high-pass filter must not exceed a threshold determined empirically);

- Control of the correlation between photoplethysmographic signals and accelerometric signals: the module of accelerometric signals recorded on three orthogonal axes of space (Ax, Ay and Az) is calculated as and, subsequently, it occurs that:

- The correlation between and (photoplethysmographic) signal recorded in the red frequency is less than a certain threshold derived empirically;

- The correlation between and (photoplethysmographic) signal recorded in the infrared frequency is less than a certain threshold derived empirically.

- If the conditions in point 1 and 2 occur, the time window from which to derive heart rate and SpO2 data is excluded from the collection of data deemed useful in the context of the study.

- Heart rate values between 40 and 180 bpm

- SpO2 values between 80 and 100%

2.5. Study Protocol and Sample

- (a)

- Sitting with the right arm leant on the table, breathing room air for 30 min

- (b)

- Calibration of sensor: this procedure requires the distal phalanx of a patient’s finger (e.g., index finger) to be placed on the photoplethysmographic sensor on the BrOxy M wearable device in order to record 90 s of red and infrared signal. Using the recorded signals, the calibration algorithm is applied as described in the patents WO2019/193196 and WO2021/069729 (see Supplementary File S1).

- (c)

- BrOxy M positioning (see Section 2.2);

- (d)

- Positioning of the single use sensor MAXALI of the reference device on the fingertip of index finger of the right hand warning the subject not to move arm and hand

- (e)

- Positioning of a single use nose clip to block the nasal airflow and start of test with the following experimental procedure: mouthpiece with sterile filter connected to a Hans Rudolph valve (one way air valve), whose inspiratory way, through a Douglas bag tubing 1.5 m long, is connected in sequence—according to time set afterwards reported, through a single channel tubing valve, to 4 (four) Douglas bag 100 lt each, continuously supplied by 4 cylinders each containing a different O2 concentration (see Table 1 after the following paragraph).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Differences between the Two Pulse Oximeters

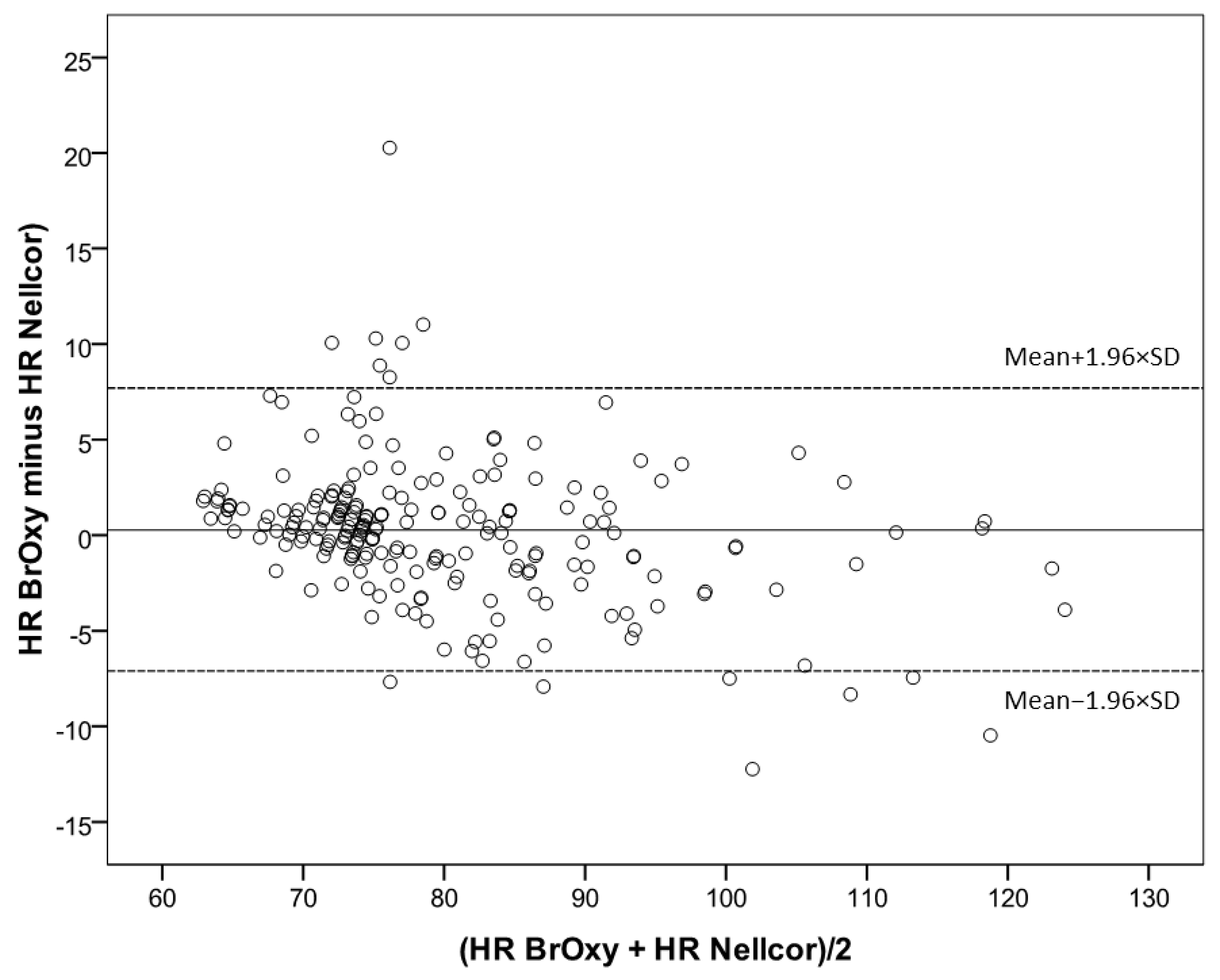

3.2. Bland-Altman Plot

3.3. Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive and Negative Predictive Values

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hajat, C.; Stein, E. The global burden of multiple chronic conditions: A narrative review. Prevent Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories 1980–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1736–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanfleteren, L.E.G.W.; Spruit, M.A.; Groenen, M.; Gaffron, S.; Van Empel, V.P.M.; Bruijnzeel, P.L.B.; Rutten, E.P.A.; Roodt, J.O.; Wouters, E.F.M.; Franssen, F.M.E. Clusters of Comorbidities Based on Validated Objective Measurements and Systemic Inflammation in Subjects with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 187, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, J.; Edwards, L.D.; Agustí, A.; Bakke, P.; Calverley, P.M.; Celli, B.; Coxson, H.O.; Crim, C.; Lomas, D.A.; Miller, B.E.; et al. Comorbidity, systemic inflammation and outcomes in the ECLIPSE cohort. Respir. Med. 2013, 107, 1376–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Remoortel, H.; Hornikx, M.; Langer, D.; Burtin, C.; Everaerts, S.; Verhamme, P.; Boonen, S.; Gosselink, R.; Decramer, M.; Troosters, T.; et al. Risk Factors and Comorbidities in the Preclinical Stages of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 189, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, G.; Fabiani, F.; Forte, S.; Napolitano, M.; Balzano, G.; Bonini, M.; De Simone, G.; Fuschillo, S.; Pentassuglia, A.; Pasqua, F.; et al. INDACO project: COPD and link between comorbidities, lung function and inhalation therapy. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2015, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Müllerova, H.; Agusti, A.; Erqou, S.; Mapel, D.W. Cardiovascular comorbidity in COPD: Systematic literature review. Chest 2013, 144, 1163–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.K.; Heiss, G.; Barr, R.G.; Chang, P.P.; Loehr, L.R.; Chambless, L.E.; Shahar, E.; Kitzman, D.W.; Rosamond, W.D. Airflow obstruction, lung function, and risk of incident heart failure: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2012, 14, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huiart, L.; Ernst, P.; Suissa, S. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in COPD. Chest 2005, 128, 2640–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wedzicha, J.A.; Seemungal, T.A. COPD exacerbations: Defining their cause and prevention. Lancet 2007, 370, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, G.C.; Seemungal, T.A.; Bhowmik, A.; Wedzicha, J.A. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2002, 57, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seemungal, T.A.; Donaldson, G.C.; Paul, E.A.; Bestall, J.C.; Jeffries, D.J.; Wedzicha, J.A. Effect of exacerbation onquality of life in subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998, 157, 1418–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anzueto, A.; Leimer, I.; Kesten, S. Impact of frequency of COPD exacerbations on pulmonary function, health status and clinical outcomes. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2009, 4, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Donaldson, G.C.; Wilkinson, T.M.; Hurst, J.R.; Perera, W.R.; Wedzicha, J.A. Exacerbations and time spent outdoors in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 171, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourbeau, J. Activities of life: The COPD subject. COPD 2009, 6, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suissa, S.; Dell’Aniello, S.; Ernst, P. Long-term natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Severe exacerbations and mortality. Thorax 2012, 67, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soler-Cataluña, J.J.; Martınez-Garcıa, M.A.; Roman Sanchez, P.; Salcedo, E.; Navarro, M.; Ochando, R. Severe acute exacerbations and mortality in subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2005, 60, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boudestein, L.C.M.; Rutten, F.H.; Cramer, M.J.; Lammers, J.W.J.; Hoes, A.W. The impact of concurrent heart failure on prognosis in subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2009, 11, 1182–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguin, F.; Folch, E.; Redd, S.C.; Mannino, D.M. Comorbidity and mortality in COPD-related hospitalizations in the United States, 1979 to 2001. Chest 2005, 128, 2005–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, D.A.; Sverzellati, N.; Travis, W.D.; Brown, K.K.; Colby, T.V.; Galvin, J.R.; Goldin, J.G.; Hansell, D.M.; Inoue, Y.; Johkoh, T.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A Fleischner Society Withe Paper. Lancet Respir. Med. 2018, 6, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Rochwerg, B.; Zhang, Y.; Cuello-Garcia, C.; Azuma, A.; Behr, J.; Brozek, J.L.; Collard, H.R.; Cunningham, W.; Homma, S.; et al. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline: Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Update of the 2011 Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, e3–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, A.S.; McSharry, D.G.; Malhotra, A. Adult obstructive sleep apnoea. Lancet 2014, 383, 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stöwhas, A.C.; Lichtblau, M.; Bloch, K.E. Obstruktives Schlafapnoe-Syndrom [Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome]. Praxis 2019, 108, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vontetsianos, T.; Giovas, P.; Katsaras, T.; Rigopoulou, A.; Mpirmpa, G.; Giaboudakis, P.; Koyrelea, S.; Kontopyrgias, G.; Tsoulkas, B. Telemedicine-assisted home support for subjects with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Preliminary results after nine-month follow-up. J. Telemed. Telecare 2005, 11 (Suppl. 1), 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paré, G.; Sicotte, C.; St-Jules, D.; Gauthier, R. Cost-minimization analysis of a telehomecare program for subjects with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Telemed. J. E-Health 2006, 12, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De San Miguel, K. Telehealth Remote Monitoring for Community-Dwelling Older Adults with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Telemed. J. E-Health 2013, 19, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Lee, S.H. Effectiveness of tele-monitoring by subject severity and intervention type in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease subjects: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 92, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardinge, M.; Annandale, J.; Bourne, S.; Cooper, B.; Evans, A.; Freeman, D.; Green, A.; Hippolyte, S.; Knowles, V.; MacNee, W.; et al. British Thoracic Society guidelines for home oxygen use in adults. Thorax 2015, 70, i1–i43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caminati, A.; Cassandro, R.; Harari, S. Pulmonary hypertension in chronic interstitial lung diseases. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2013, 22, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curig, O.; Prys-Picard, M.A.; Kellett, F.; Niven, R.M. Disproportionate Breathlessness Associated With Deep Sighing Breathing in a Subject Presenting With Difficult-To-Treat Asthma. Chest 2006, 130, 1723–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küpper, T.; Milledge, J.S.; Hillebrandt, D.; Kubalova, J.; Hefti, U.; Basnayt, B.; Gieseler, U.; Pullan, R.; Schöffl, V. Raccomandazioni Ufficiali Della Commissione Medica UIAA. V2(15), 7/2015. 2009. Available online: www.theuiaa.org (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Oxitone 1000M—World’s First FDA-Cleared Wrist-Sensor Pulse Oximetry Monitor. Available online: https://www.oxitone.com/oxitone-1000m/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- The Next Generation of Health-AI. Available online: https://www.bio-beat.com/ (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Watching Over You. Available online: https://www.cardiacsense.com/ (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Unlock Health Insights. Available online: https://polsowatch.com/ (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Technology That’s Built to Move. Available online: https://spryhealth.care/ (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Kirszenblat, R.; Edouard, P. Validation of the Withings Scan Watch as a Wrist-Worn Reflective Pulse Oximeter: Prospective Interventional Clinical Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e27503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, S.; Sica, A.L.; Wang, J.; Lakticova, V.; Greenberg, H.E. Respiratory effort-related arousals contribute to sympathetic modulation of heart rate variability. Sleep Breath 2013, 17, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, T.; Ewig, S.; Schafer, H.; Jelen, E.; Omran, H.; Lüderitz, B. Heart rate variability in patients with sleep-related breathing disorders. Cardiology 1996, 87, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/pulse-oximeters-premarket-notification-submissions-510ks-guidance-industry-and-food-and-drug (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986, 1, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH); U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Food and Drug Administration; Center for Devices and Radiological Health; Office of Device Evaluation, Division of Anesthesiology, General Hospital, Infection Control, and Dental Devices Anesthesiology and Respiratory Devices Branch. Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. 2013. Available online: https://www.fda.gov (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Pretto, J.J.; Roebuck, T.; Beckert, L.; Hamilton, G. Clinical use of pulse oximetry: Official guidelines from the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand. Respirology 2014, 19, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.W.; Allen, N.B. Accuracy of Consumer Wearable Heart Rate Measurement During an Ecologically Valid 24-Hour Period: Intraindividual Validation Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e10828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.M.; Kang, B.J.; Yun, H.Y.; Jeon, B.; Bang, J.Y.; Noh, G.J. Performance of the MP570T pulse oximeter in volunteers participating in the controlled desaturation study: A comparison of seven probes. Anesth. Pain Med. 2020, 15, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiner, J.R.; Severinghaus, J.W.; Bickler, P.E. Dark skin decreases the accuracy of pulse oximeters at low oxygen saturation: The effects of oximeter probe type and gender. Anesth. Analg. 2007, 105 (Suppl. 6), S18–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, A.I.; Charpignon, M.; Kim, H.; Josef, C.; de Hond, A.A.H.; Fojas, J.J.; Tabaie, A.; Liu, X.; Mireles-Cabodevila, E.; Carvalho, L.; et al. Analysis of Discrepancies Between Pulse Oximetry and Arterial Oxygen Saturation Measurements by Race and Ethnicity and Association With Organ Dysfunction and Mortality. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2131674, Erratum in JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e221210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiles, M.D.; El-Nayal, A.; Elton, G.; Malaj, M.; Winterbottom, J.; Gillies, C.; Moppett, I.K.; Bauchmuller, K. The effect of subject ethnicity on the accuracy of peripheral pulse oximetry in subjects with COVID-19 pneumonitis: A single-centre, retrospective analysis. Anaesthesia 2022, 77, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiolo, C.; Mohammed, E.I.; Fiorani, C.M.; De Lorenzo, A. Home telemonitoring for subjects with severe respiratory illness: The Italian experience. J. Telemed. Telecare 2003, 9, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, N.B.; Der, E.; Ruggerio, C.; Heidenreich, P.A.; Massie, B.M. Prevention of hospitalizations for heart failure with an interactivehome monitoring program. Am. Heart J. 1998, 135, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, R.S.; Kline, S.E.; Schmalfuss, C.M.; Carver, H.M.; Aranda, J.M.; Pauly, D.F.; Hill, J.A.; Neugaard, B.I.; Chumbler, N.R. Early outcomes of a care coordination-enhanced telehome care program for elderly veterans with chronic heart failure. Telemed. E-Health 2005, 11, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordisco, M.E.; Beniaminovitz, A.; Hammond, K.; Mancini, D. Use of telemonitoring to decrease the rate of hospitalization in subjects with severe congestive heart failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 1999, 84, 860–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.S.; Callahan, C.W.; Sheets, S.J.; Moreno, C.N.; Malone, F.J. An Internet-based store-and-forward video home telehealth system for improving asthma outcomes in children. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2003, 60, 1976–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, J.; Connor, S.; Tolley, K. An evaluation of the west Surrey telemedicine monitoring project. J. Telemed. Telecare 2003, 9 (Suppl. 1), S39–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, N.; Sultan, H. Telehealth as ‘peace of mind’: Embodiment, emotions and the home as the primary health space for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder. Health Place 2013, 21, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, E. Cost comparison between telemonitoring and usual care of heart failure: A systematic review. Telemed. J. E-Health 2008, 14, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White-Williams, C.; Unruh, L.; Ward, K. Hospital utilization after a telemonitoring program: A pilot study. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 2015, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardini, C. Machine learning in oncology: A review. Ecancermedicalscience 2020, 14, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S: Food & Drug Administration (FDA). Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Software as a Medical Device. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/software-medical-device-samd/artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning-software-medical-device#regulation (accessed on 29 November 2021).

| Plateu n. | Range SpO2 (%) | Inhaled Solution | Plateu Duration | N. of Measures of SpO2 and HR Extracted from Recordings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (I) | 95–100 (target 97%) | Ambient air (medical air) | 2.5-’ | 8 |

| (II) | 90–94 (target 92%) | O2 15% + N 85% | 2.5-’ | 8 |

| (III) | 85–89 (target 87%) | O2 13% + N 87% | 2.5-’ | 8 |

| (IV) | 80–84 (target 82%) | O2 11% + N 89% | 2.5’ | 8 |

| Total | 32 measures | |||

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Participants | 12 |

| Men | 10 (83.3) |

| Age, years, mean ± SD [range] | 37 ± 9 (20–51) |

| Skin color: | |

| white | 8 (66.7) |

| black (Fitzpatrick scale, type V-VI) | 4 (33.3) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 26.2 ± 3.3 |

| Data pairs | 219 |

| Men | 183 (83.6) |

| Age, years, mean ± SD [range] | 37 ± 9 [20–51] |

| Skin color: | |

| white | 158 (72.1) |

| black | 61 (27.9) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 26.1 ± 3.3 |

| BrOxy M SpO2, %, mean ± SD | 91.0 ± 6.1 |

| Nellcor SpO2%, mean ± SD | 90.8 ± 6.3 |

| Nellcor SpO2 ≤ 94% | 147 (67.1) |

| Nellcor SpO2 ≤ 90% | 95 (43.4) |

| BrOxy M HR, bpm, median [range] | 77 (64–122) |

| Nellcor HR, bpm, median [range] | 76 (62–126) |

| Nellcor SpO2 | Bias (95% CI) 1 % | ARMS % | Lower Limit of Agreement 2 % | Upper Limit of Agreement 3 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80% to 100% | 0.18 (−0.17, 0.54) | 2.7 | −5.1 | 5.5 |

| ≤94% | 0.57 (0.08, 1.06) | 3.0 | −5.2 | 6.4 |

| ≤90% | 0.94 (0.27, 1.61) | 3.3 | −5.5 | 7.4 |

| Nellcor SpO2 | Bias (95% CI) 1 | ARMS | LLA 2 | ULA 3 | MAPE ± SD % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80% to 100% | 0.25 (−0.24, 0.75) | 3.7 | −7.1 | 7.7 | 3.20 ± 3.3 |

| ≤94% | −0.01 (−0.65, 0.63) | 3.9 | −5.2 | 6.4 | 3.16 ± 3.4 |

| ≤90% | −0.39 (−1.12, 0.34) | 3.6 | −5.5 | 7.4 | 3.02 ± 2.7 |

| r | r2 | B | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpO2 80% to 100% | 0.20 | 0.041 | |||

| average 1 | 0.05 | –0.11, 0.01 | ns | ||

| age | 0.01 | –0.07, 0.05 | ns | ||

| sex(ref females) | 0.88 | –0.21, 1.97 | ns | ||

| skin color(ref black) | 0.16 | –1.26, 0.93 | ns | ||

| BMI | 0.11 | –0.30, 0.08 | ns | ||

| SpO2 ≤ 94% | 0.23 | 0.052 | |||

| average 1 | 0.06 | –0.07, 0.18 | ns | ||

| age | 0.02 | –0.10, 0.06 | ns | ||

| sex(ref females) | 1.31 | –0.26, 2.89 | ns | ||

| skin color(ref black) | 0.61 | –2.26, 1.03 | ns | ||

| BMI | 0.14 | –0.40, 1.12 | ns | ||

| SpO2 ≤ 90% | 0.32 | 0.10 | |||

| average 1 | 0.17 | –0.08, 0.42 | ns | ||

| age | 0.04 | –0.08, 0.15 | ns | ||

| sex(ref females) | 1.66 | –0.80, 4.11 | ns | ||

| skin color(ref black) | 0.13 | –2.76, 2.50 | ns | ||

| BMI | 0.34 | –0.76, 0.08 | ns |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marinari, S.; Volpe, P.; Simoni, M.; Aventaggiato, M.; De Benedetto, F.; Nardini, S.; Sanguinetti, C.M.; Palange, P. Accuracy of a New Pulse Oximetry in Detection of Arterial Oxygen Saturation and Heart Rate Measurements: The SOMBRERO Study. Sensors 2022, 22, 5031. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22135031

Marinari S, Volpe P, Simoni M, Aventaggiato M, De Benedetto F, Nardini S, Sanguinetti CM, Palange P. Accuracy of a New Pulse Oximetry in Detection of Arterial Oxygen Saturation and Heart Rate Measurements: The SOMBRERO Study. Sensors. 2022; 22(13):5031. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22135031

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarinari, Stefano, Pasqualina Volpe, Marzia Simoni, Matteo Aventaggiato, Fernando De Benedetto, Stefano Nardini, Claudio M. Sanguinetti, and Paolo Palange. 2022. "Accuracy of a New Pulse Oximetry in Detection of Arterial Oxygen Saturation and Heart Rate Measurements: The SOMBRERO Study" Sensors 22, no. 13: 5031. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22135031

APA StyleMarinari, S., Volpe, P., Simoni, M., Aventaggiato, M., De Benedetto, F., Nardini, S., Sanguinetti, C. M., & Palange, P. (2022). Accuracy of a New Pulse Oximetry in Detection of Arterial Oxygen Saturation and Heart Rate Measurements: The SOMBRERO Study. Sensors, 22(13), 5031. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22135031