1. Introduction

Exoskeletons and exoskeletal robots are wearable devices based on a mechanical structure that conceptually mirrors the skeletal structure of a limb or of the involved body-part. In recent decades and still today, they are the subject of much research, considering the advantages that they can bring to the end-user.

These devices can be classified according to various aspects. Classifications can be based, for instance, on the purpose, on the body part to which they are addressed, on the used actuation technology, or on the type of interaction with the user. Additionally, human–robot interaction through robotic exoskeletons can be aimed at different purposes, and four main classes can be identified: rehabilitation, assistance, performance augmentation and haptic interaction [

1].

Robotic rehabilitation provides repetitive, flexible and customizable exercises that complement physiotherapist work, aimed at the functional recovery of patients who report impairments or disorders deriving, e.g., from stroke, brain or spinal cord injuries (SCI), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), orthopaedic surgery, or cerebral palsy (CP) [

2]. Further significant advantages are associated with the use of robotic devices in rehabilitation, including, e.g., intense repetitive training, performing at home rehabilitation with remote control, automatically adjusting the device support based on the patient progressive recovery [

3,

4], increasing the patient engagement through computerized activities proposed in the form of games, monitoring progress through the assessment of outcomes in an objective way [

5] and reducing the overall cost of rehabilitative care given the aging of our society [

6,

7].

Assistive robotic exoskeletons can be effectively used to help the elderly or permanently injured in carrying out the most important activities of daily living (ADLs) with more independence, attempting to compensate for disabilities or partial functional loss [

8]. Walking, grasping and handling objects and eating are some of these core activities.

In the context of work or military duties, which involve very intense stresses to the human skeletal and muscular structures, the use of an exoskeletal robot can lead to a significant improvement in the operating conditions and a reduction in the physical injuries risks associated with these types of tasks [

9]. Specifically designed exoskeletons for performance augmentation combine the strength of a robot with the intelligence of a human to perform tasks that could hardly be done either by a man alone or robot alone. Furthermore, haptic interfaces intended for augmented or virtual reality applications [

8] can be developed through wearable exoskeletons.

Considering the anatomical district to which the exoskeleton is aimed, we identify devices for the upper limb (upper limbs exoskeletons ULE), for the lower limb (lower limbs exoskeleton LLE), for the whole body or for a specific anatomical district. A dedicated class is often considered for the hand (hand exoskeletal devices HED), due to the fundamental role that it plays in the ADLs. Likewise, the trunk is often considered individually, given the particular characteristics (such as high amplitude) of the associated movements. For each one of these classes, the adopted design solutions are strongly influenced by the exoskeleton’s purpose.

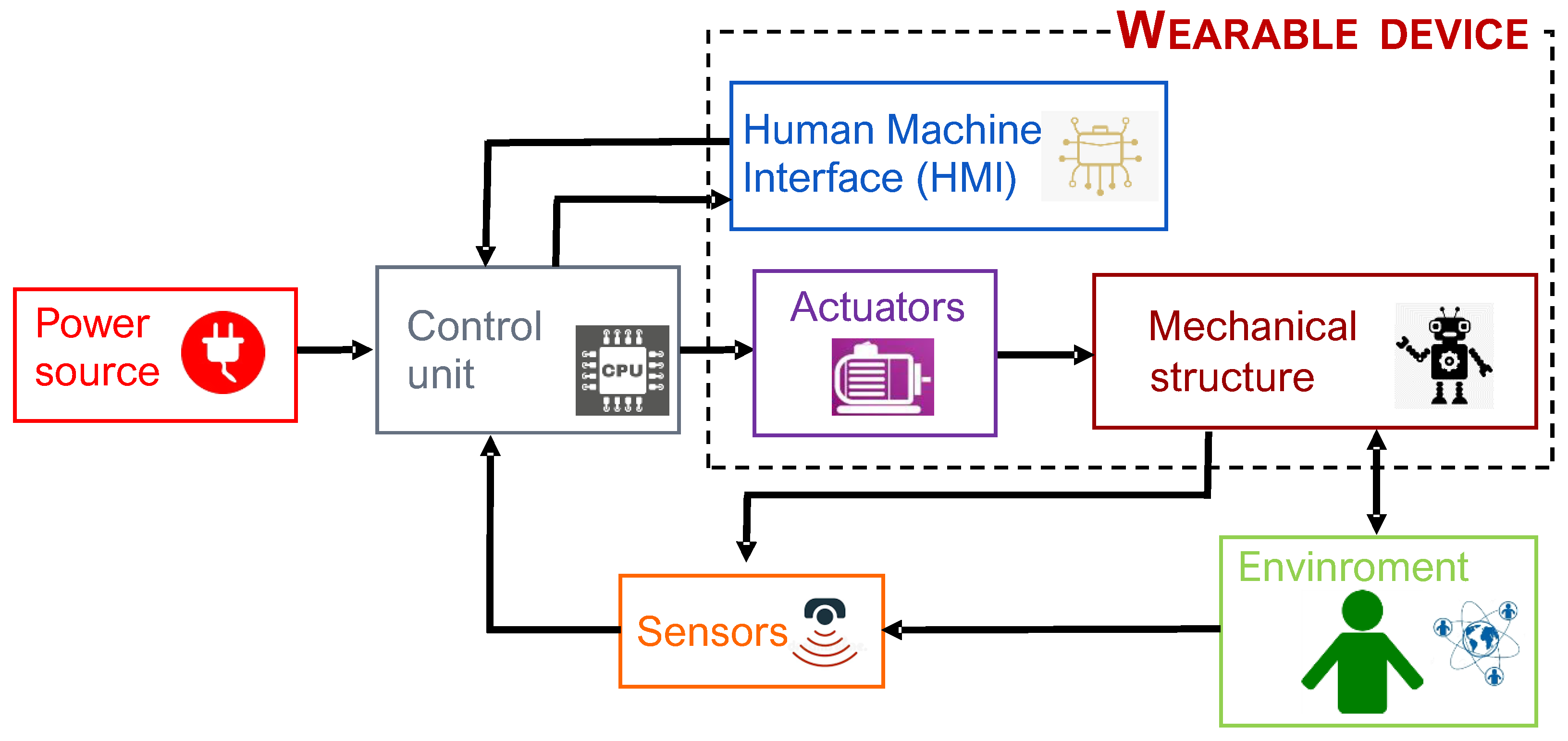

Similarly to any other type of robot, a robotic exoskeleton is a complex system of interrelated parts. As the block-diagram of

Figure 1 depicts, the following set of fundamental elements can be typically identified:

a mechanical structure, with degrees of freedom (DoF) consistent with the robot’s purpose;

actuators, which generate the required mechanical power;

one or more sources of energy;

proprioceptive and exteroceptive sensors, providing information on the machine functional status and on the interaction with the user and/or the environment;

a control unit, processing the signals transmitted by the sensors and instructing the motor controllers;

human/machine interface(s) receiving information/instructions from users (either the therapist or the user) and providing online feedback; and

the environment.

The environment, purpose and working conditions strongly affect the requirements that a device is expected to fulfill [

10]. For instance, traditional industrial robots that operate in a structured environment can rely on the design philosophy “stiffer is better”, as the main requirements are high precision and speed. Unlike these, a wearable exoskeleton operates in an unstructured environment and must guarantee as main features safety comfort for the user, easy control and low encumbrance [

11]. These different design specifications significantly influence the choice of system components and related technologies [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

In the mechanical design, a fundamental choice concerns the number of DoF of the system, that is the sum of all independent movements (i.e., translations/linear displacements and rotations) that can be performed in all the joints of the device [

17]. The number of DoF is defined in order to determine the exact position and orientation of all segments of the device. As the number of degrees of freedom increases, the mechanical complexity grows as well, but the handling possibilities also increase. The DoF of the device may be active or passive, whether they are actuated or not. An exoskeleton may have all the DoF active, only some of them or none.

In the first two cases, it is defined an active device and as a passive device in the latter. Finally, we have two further definitions of devices: haptic and coaching devices. Haptic exoskeletons interact with the user through the sense of touch, and their main function is not to cause or to resist movement, but rather to provide the user with tactile sensation.

Coaching devices are non-actuated devices that do not generate any forces but provide different feedback; they can serve as an input interface for interaction with games in virtual reality, such as systems using video-based motion recognition (e.g., Kinect®, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

The energy is provided by the power source. The control unit, based on the indications coming from the human–machine interface (HMI) and on the data acquired by the sensors, decides how the actuators must be powered [

3]. This control unit block therefore contains, in addition to a microprocessor that manages the command logo, electrical components that actually provide power to the actuators. The control unit must detect the user intention, provide safe movements and should be structured to favor the portability of the device. Actuators provide motion and forces or torques to the mechanical system.

The set of mechanical system and actuators constitutes the wearable device. Sometimes the HMI devices are an integral part of this device, and sometimes they are external, as well as for the sensors and the control unit. This depends on the structure of each device. The device interacts with the environment, which defines the limits to the movement and imposes boundary conditions for the functioning, such as the rehabilitation strategy, the operating modes and the methods for evaluating the results.

The actuation units can be placed either distally or proximally with respect to the ground of the kinematic frame, and the position of the motors affects the dynamics of the system. The strategy of placing the actuators directly at the joint level avoids the need of a transmission mechanism but increases the inertia of the moving parts, resulting in a less transparent control and in a more power-consuming system. With the choice of proximally placed actuators, a transmission mechanism is required to transmit the torque at the distal location. This reduces the inertia at the joint but also introduces the challenge of compensating for the nonlinear dynamics that may arise in the transmission, such as hysteresis and friction.

Another design choice that significantly influences many fundamental aspects, such as the structure, weight, energy consumption and performance, concerns the technology for the generation of mechanical power. A wide variety of actuation technologies have been used to develop exoskeletal robotic devices. These can be classified according to the nature of the energy source used to generate mechanical power: hydraulic, pneumatic and electric actuation are the most common.

Similarly, different technologies are used for sensing purposes in exoskeletons, such as measures relating to the movement of specific limbs [

18], forces or torques exchanged between device and user, bio-signals, such as electromyography signals (EMGs) [

19], electroencephalography signals (EEGs) and mechanomyography signals (MMG) to be used for device control or validation [

20,

21,

22], etc.

The mechanical structure (and consequently DoF and concerned body-part), actuation, sensors, HMI, control strategy and purpose are the main aspects on which a review of the research activity on exoskeletons may be focused. Several review articles on exoskeletons have been published in recent years, and those taken into consideration are collected in

Table 1. Most of them concern devices dedicated to a specific body part, i.e., the upper or lower limbs, and, among the more recent publications, only the review of Agarwal et al. [

1], published in 2019, addresses exoskeletons in a more general way.

The authors, in the first part of their work, analyze the state of the art of exoskeletons used for medical applications and for performance augmentation; in the second part, they examine the sub-components, that is the mechanical design, actuation, sensing, materials and control; in the third part, they describe two case studies, Harmony (for shoulder and upper limb rehabilitation) and Maestro (for hand rehabilitation) and finally discuss ongoing challenges and future directions. The review papers of Sanjiuan et al., in 2020 [

17], of Rehmat et al., in 2018 [

23], of Blank et al. [

24], of Manna et al. [

25] and of Maciejasz et al. [

26] dated 2014, concern upper limb rehabilitation.

Sanjiuan et al. focused their work on construction solutions based on cable transmission. Rehmat et al. conducted a systematic review on the use of robotic exoskeleton systems for upper limb rehabilitation deepening typical mechanical structures and control strategies for exoskeletons in clinical rehabilitation conditions. The work of Blank et al. deals with robotic stroke rehabilitation for upper-limb therapy focusing on patients engagement. Manna et al. focused their review on a comparative study of actuation systems. Maciejasz et al. developed an extensive and thorough survey on devices for upper limb rehabilitation, including the analysis of over 120 devices. A greater number of reviews in recent years concern exoskeletons for the lower limbs.

Hussain et al. [

27] in 2021 proposed a review of materials, actuation and manufacturing methods in exoskeleton robots for lower limb assistance. Shi et al. [

28] examined the topics of gait analysis and mechanical design, actuation and control of lower limb exoskeletons. Sanchez-Villamañan et al. [

29] reviewed the mechanical design principles of compliant lower limb exoskeletons. Al-Shuka et al. [

9] covered biomechanical modeling, actuation and multi-level control strategies of power augmentation lower limb exoskeletons.

Zhang et al. [

30] systematically reviewed the developments of robotic lower-limb rehabilitation after stroke, providing a classification, a comparison and a design overview of the driving modes, training paradigm, control strategy and gait perception. Louie et al. [

31] proposed a scoping review with the aim of mapping the use of robotic exoskeletons for gait rehabilitation in adults. Chang et al. [

32] reviewed the lower-limb exoskeletons to restore gait for individuals with paraplegia. Only one recent review devoted to current hand rehabilitation technologies was found [

33], dated 2012.

Within this framework, the current work differs from all the most recent reviews, as we aim at providing an in-depth analysis of the literature about exoskeletons (i) without limitations related to the involved anatomical district and (ii) deepening the most recent trends on both implemented sensors and actuation technologies.

Compared to Agarwal’s work, the proposed review conducts a more extensive investigation of the scientific literature classifying the documents at different levels to extrapolate significant indications on the trends of research activity in this area. Furthermore, the analysis of actuation and sensing techniques is developed with a greater level of detail, as the review particularly focuses on these two aspects. The current work presents an approach similar to the one proposed by Maciejasz et al., in their review of 2014 [

26]; nevertheless, the range of interest is here more extensive, as we aim at exoskeletons in general and not only at those for upper limbs, and the literature analysis is updated to date.

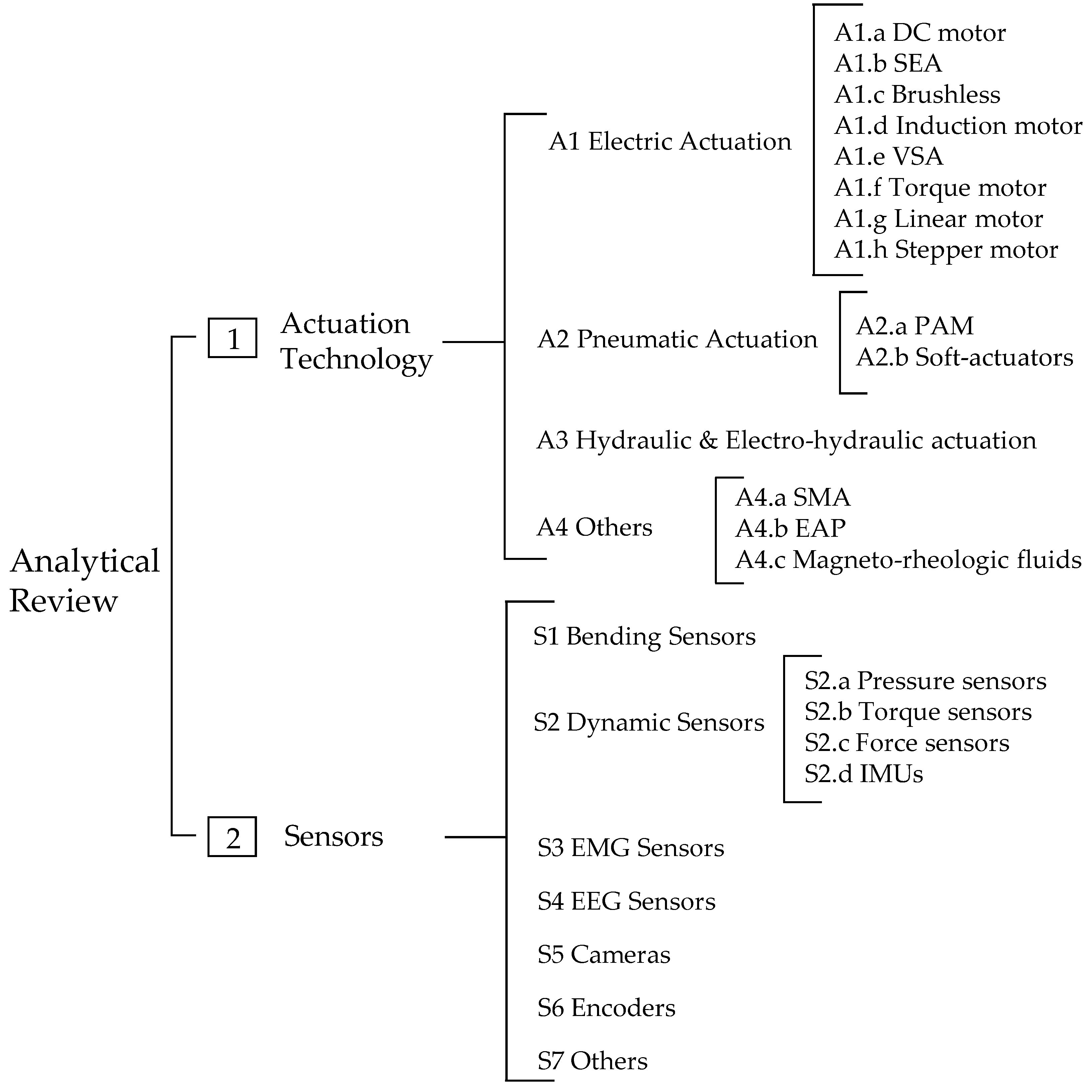

The final aim is to trace a picture of the main solutions of exoskeletons, as complete as possible, for all the different uses and for all the different parts of the body. In detail, the proposed literature review presents two different analysis levels: a prospective review, or an observational study of the publication distribution over time, by purpose, by involved body district, by device type, focus and design solutions; and an analytical review, consisting of an in-depth study of the more recent and most used technologies for exoskeleton actuation and sensors.

Furthermore, cross-analyses were carried out to highlight possible correlations between the investigated issues. The identification of these correlations can provide useful information on the technological choices made for the different types and uses of exoskeletons, as well as on the results obtained with these choices.

Figure 2 schematically shows the two main levels of analysis (prospective and analytical) and the cross analyses.

An investigation on technical solutions for exoskeleton design choices with a particular focus on sensors and actuation technologies can be a useful contribution to future projects, highlighting what has already been considered and allowing useful insights from the successes but also from the shortcomings of other works. The aim of the review work is, therefore, to summarize the most recent and widespread solutions for exoskeleton development, which may be a valuable source of information for engineers, physiotherapists and exoskeleton developers in their activity.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the research method in terms of the data selection protocol, perspective and analytical review.

Section 3 reports the results of the prospective review, whereas

Section 4 presents the results of the analytical review, declined for actuation and sensing technology.

Section 5 (conclusions) summarizes the more significant findings of the review work.

3. Prospective Review

For the prospective review of the literature, different aspects were considered, i.e., purpose, focus, anatomical districts, device type and design solutions. To evaluate the literature by purpose, the selected documents were analyzed in terms of distribution among categories as a whole (

Figure 6) and by year (

Figure 7). The data reveal that most of the exoskeletons were conceived for medical applications, whereas only a limited number of devices were envisioned as haptic systems.

The predominance of papers in the category p1 rehabilitation/medical applications emerges both in terms of absolute numbers and in terms of the relative relevance of this category with respect to the others by year. The trend shown in

Figure 7 reveals a significant increase in research activity on exoskeletons for medical applications since 2019.

The analysis of the dataset by focus is synthesized in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, describing the documents distribution among categories in aggregated form and by year. Both the graphs reveal a remarkable interest of the scientific community towards the actuation system (f2). This trend could be expected if considering that actuator dimensions and weight are still critical elements of the overall design of exoskeletons. In addition, the proposed classification strategy could penalize the number of papers actually classified in the category f1 Sensors. In fact, several works focus on algorithms, data fusion techniques and control strategies, particularly among the most recent literature: those contributions, though, are primarily assigned to the category Others (e.g., [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]).

The trends of Focus by Year (

Figure 9) and Purpose by Year (

Figure 7) show that 2013 marked the beginning of a growth in scientific production with an almost constant slope; the same year also identifies the starting event in the growth of works on exoskeletons for rehabilitation/medical purposes, whereas the growth phase for assistive devices only begins in 2016. In addition, 2016 also marks the beginning of a greater research in actuation systems. These last two trends are most likely correlated, as portable assistive devices require more energy-efficient, more compact, less heavy and more dynamically performing actuation systems.

The analysis by anatomical districts highlights the main presence of exoskeletons devoted to the lower limb and to the knee joint in particular. As

Figure 10 depicts, the lower limb category collects more than twice the number of exoskeletons for the upper limb. This behavior could be expected, given that the functional movements of the lower limb are less complex than the ones assured by the upper limb, involve cyclic and well known tasks (e.g., gait) and given that damage or impairment at the lower limb strongly affects the subject’s quality of life.

For those devices, some design challenges still unresolved are regarding the dimensions and portability of the system, battery time-span and user comfort. For the upper limbs, exoskeletons must face different technological challenges, for instance to deal with the anatomical complexity of the shoulder joint. In this analysis, the wrist was considered in both the upper limb and hand category, but each contribution was classified in one of the two subclasses depending on the focus of the exoskeleton.

The hand was considered an independent anatomical district with respect to the upper limb according to a functional rationale: in fact, given the different functional role of hand and upper limb, exoskeletons are also more commonly devoted to the treatment of one of those categories. The hand offers peculiar anatomical conditions, such as non-negligible effects due to soft tissue artifact [

48]; this introduces specific technical challenges, for example in the joining at the finger level, that require dedicated solutions (e.g., digits).

For this reason, particular relevance is given in documents to the possibility of multi-fingers treatments, and often particular attention is paid to the management of the thumb, independently as in the works by Agarwal et al. [

49] and Wang et al. [

50], or with other fingers (e.g., [

51,

52,

53]). The trunk is specifically addressed in the paper by Ko et al. of 2018 [

54], although the stabilization of the trunk is considered in clinical practice to be a fundamental step and a pre-requisite for the enrollment in several rehabilitation training paths.

The analysis of the documents by device type allows discriminating among exoskeletons that enable passive or active-assisted rehabilitation.

Figure 11 synthesizes the distribution of the devices in the different categories; actuated exoskeletons cover almost the full amount of devices. In this classification, some exoskeletons could be mapped in more categories; this happens when the device is explicitly described as working according to different configurations (e.g., as an actuated or unactuated device).

Evaluating the exoskeletons by design solutions (

Figure 12), most of the documents explicitly refer to transmission and joining details or allow capturing hints about the adopted technical solutions. For the transmission, most of the exoskeletons are grounded on cable-based systems; however, linkages are also a spread solution to connect rigid bodies of the kinematic chain and assure the motion transmission. For the joining between human and machine, different solutions are presented, but the most commonly adopted are strap-based systems. In the subclass ds3.d other, braces and gloves are often used, but rubber and foam are also adopted, integrating the rigid connections [

53,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63].

Portability of the exoskeletons is a technical characteristic analyzed in about the 20% of the documents, whereas a dedicated analysis can be performed on active and passive DoF. As

Figure 13 depicts at a glance, from a general perspective, actuated DoF are less frequent than passive joints, and a lower number of DoF is preferred for both active and passive DoF. These trends fit well with the tendency towards simple and compact design strategies. Nevertheless, opposite solutions, which favor DoF redundancy despite the kinematic complexity, are also present; those solutions tend to ease complementary factors, such as the control management of the device.

For purpose and anatomical districts, a cross analysis was performed, and the classification results are reviewed in

Table A1 and

Figure 14 and

Figure 15. The trunk district was not included in this cross analysis due to the very limited number of contributions. Rehabilitation/medical exoskeletons are predominant for ULE, hand and forearm exoskeletons, while assistive devices are predominant for LLE. Allowing paraplegic people to regain the ability to walk is an important challenge that has led to intense research on assistive devices for the lower limbs. The growing demand for robotic devices for elbow, hand and shoulder rehabilitation and, in particular, for portable devices that allow home therapy, is motivated by our aging society.

The increase in people’s life expectancy leads to growth in post-stroke patients affected by hemiparesis; this explains the prevalence of devices dedicated to this purpose for the upper limbs and the hand. The power/performance augmenting exoskeletons are developed for all the anatomical districts, with a very similar percentage between ULE (12.73%), LLE (13.04%) and hand (10.26%); the percentage reaches 26% in haptic exoskeletons, but this is not a significant value given the small number of devices. Analyzing the distribution of exoskeleton purpose vs. the anatomical district, it emerges that the predominance of LLE is confirmed regardless of the purpose of the device, and, in assistive devices, it has the highest percentage (as noted above).

4. Analytical Review

To perform an analytical review of the literature, an evaluation of the documents with respect to the specific aspects of sensors and actuation technologies was performed.

For the analysis of the actuators implemented in the identified exoskeletons,

Figure 16 presents the detected power source by type. An electric power source represents the most common solution, whereas pneumatic and hydraulic solutions follow. The final class None collects the exoskeletons without external power actuation.

Figure 17 depicts the presence of references to the specific subclasses in the analyzed documents at a glance. Likewise,

Figure 18 synthesizes the occurrences of the different kinds of sensors in the evaluated dataset.

The following sub-paragraphs show the results and the related discussion with reference to the two main topics of investigation of the review: the actuation systems and the sensors. For the first topic, specific subsections are dedicated to the electric, pneumatic, hydraulic and electro-hydraulic actuation as well as to the aspects related to the motion transmission that have a close connection with the chosen actuation technique. For the sensors, dedicated insights were made for bending sensors, dynamic sensors, EMGs, EEGs, cameras and optical vision systems, encoders and other sensors.

4.1. Actuation Technologies

In the proposed analytical review, the term actuation refers to the subsystem that generates the mechanical power at the joint level, and therefore, in this discussion, the session power source, actuator type and transmission design solutions are included. Exoskeletons actuators should act similarly to biological muscles and their neuro-mechanical control, as for all robots that strictly interact with people; for this reason, new constructive solutions of actuators have been developed specifically for this application field.

Electric, pneumatic and hydraulic are the available types of power sources. The choice of the power source has a fundamental role in the device design as it influences the final system main functional characteristics, e.g., the overall dimensions, weight, stiffness, autonomy, back-drivability, control accuracy, forces and torques that can be generated.

Table A2 contains a cross-analysis of the paper distribution of power source vs. anatomical district.

Figure 19 shows how power source technologies are distributed in exoskeletons dedicated to the different anatomical districts.

Figure 20 shows how most used actuator types are distributed in exoskeletons dedicated to the different anatomical districts;

Figure 21, instead, reports for each one of the most used actuators the kind of exoskeleton, depending on the dedicated anatomical district, in which it is used. The following deductions emerge from the observation of the table. The crossed analysis confirmed what was already well known [

1,

26], i.e., most of the designed and developed devices are electrically operated.

This predominance of electric actuation is independent on the anatomical districts to which the exoskeletons is aimed at. Pneumatic and hydraulic actuation, instead, are mainly adopted in lower limb exoskeletons, while particular actuators, such as SMA, EAP or magneto-rheological fluids are very little used and never for LLE. Brushed and brushless DC motors are the most used electric actuators, and, in recent years, SEA are increasingly used.

Table A6 contains the cross-analysis of the paper distribution of power source vs. exoskeleton purpose.

Figure 22 shows how power source technologies are distributed in exoskeletons with different purpose.

Figure 23 shows how most used actuator types are distributed in exoskeletons with different purpose;

Figure 24 reports, for each of the most used actuators, the kind of exoskeleton, depending on the purpose, in which it is used.

For the most adopted electric actuators (DC, brushless and SEAs) an equal distribution between rehabilitation and assistive exoskeletons is observed. Instead, VSAs, torque and linear motors, which are overall little used, are mainly diffused in medical or for rehabilitation prototypal devices. Even the PAMs are mainly used in exoskeletons for rehabilitation, while hydraulic actuation is mainly used in assistive devices or for power/performance augmentation. The following paragraphs analyze, in detail, the main trends for the exoskeleton development for the different possible alternatives in terms of the power source.

4.1.1. Electric Actuation

Electric solution for actuation is widely used because it allows easy energy storage and supply. Electric actuators are available in a great variety of types and sizes, are reliable and allow a good control accuracy. Among the different types, brushed DC electric motors are the most widely used, followed by brushless BLDC motors. The brushed DC motor is used, in many cases, because of the simple structure of the motor itself and of its electronic drive; however, the brushes and commutator system require regular maintenance.

Therefore, the main advantages of brushless vs. brushed motors are the greater reliability, due to the lack of brushes and the better dynamic performance, allowed by a lower rotor inertia and the higher power-to-weight ratio. In some cases, direct drive torque motors, which are placed at the joints, are used. Correct actuators selection and sizing is a key step in the exoskeleton design to obtain lightweight and transparent systems.

Calanca et al., in [

64], presented a methodology based on a graphical tool that matches actuator capabilities to the task requirements, thus, showing how different design choices affect the actuator as a whole. In the proposed approach, task torques and velocities are acquired through experimental trials, repeated by different subjects; a motion capture system allows the acquiring of position and velocities, while joint torques are estimated via inverse dynamics on a multi-body human-exoskeleton model.

Once these datasets are available, the procedure guides the component selection and sizing. Similarly, Barjuei et al., in [

65], proposed an approach to the selection of a brushless BLDC motor and a gearbox transmission based on an optimization through a human–robot dynamics interaction analytical model and a mathematical relation between the weight and technical characteristics of the components. The optimization criteria are expressed in terms of the closed-loop system frequency bandwidth, system power consumption and the weight of the components and are formulated by imposing technical constraints on simulation parameters.

In some cases, the actuators or the reduction units are of non-standard design; therefore, the need to characterize them arises. Belogusev and Egorov, in [

66], presented a quick and inexpensive method for determining the efficiency of a electric actuation system, which allows higher-precision measurements. The same authors in [

67], proposed an automatic measurement process for determining the starting torque of an electric gear actuator for an exoskeleton. The method does not require expensive equipment and can be performed without dismounting the actuator from the exoskeleton.

A key feature of an exoskeleton is in not hindering the wearer’s movements to achieve comfort and safety; therefore, the joints must be back-drivable. Several authors focused on this aspect, such as Liu et al., in [

68], who tested the active joints of the developed upper-limb power-assisted exoskeleton and proved their excellent back-drivability. Safety and back-drivability requirements for exoskeleton actuation systems have favored the research and development of new electric actuation solutions, e.g., Series Elastic Actuators (SEA), Variable Stiffness Actuators (VSA), Parallel Elastic Actuators (PEA) and Magneto-Rheological Series Elastic Actuators (MRSEA). Series Elastic Actuators (SEAs) [

49,

52,

63,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74] are formed by a spring, or a spring-like component, in series with an electric actuator (usually a BLDC or a DC motor).

The springs ensure that the coupling between the user and the motor be compliant, thereby, protecting the users body from impact loads and other undesirable interactions. Furthermore, the compliance introduced by the spring facilitates a torque-based control strategy by transforming the torque/force control problem into a position control problem based on the measurement of the springs deformation. These actuators, widely used in exoskeletons, allow a smooth force transmission, accurate force control, lower output impedance, shock tolerance, energy efficiency and back-drivability in human–robot physical interactions.

The spring acts as an impact damper and reduces the actuator inertia felt by the user, thus, allowing the user to increase safety and comfort. A further advantage is the peak motor power reduction exploiting the spring capacity of storing energy. The main disadvantages of SEAs are the reduction of the positioning bandwidth and the rise in the number of mechanical parts with a possible consequent overall weight increase. To improve the exoskeleton dynamics when SEAs are used, Vantilt et al., in [

72], presented a novel model-based torque control, based on extensive modeling of the exoskeleton and of its interactions with the environment. Various other issues on exoskeletons with SEAs are dealt with in the literature.

Aguirre-Ollinger and Yu, in 2021 in [

69], proposed a force feedback control for a lower-limb assistive exoskeleton driven by variable-structure SEAs coupled via Bowden cables and proved its stability. The SEAs variable structure refers to the effect of the commanded force that allows varying the stiffness between two levels. Marconi et al., in 2019 in [

52], presented a novel series-elastic actuators (SEA) architecture, for a hand exoskeleton that directly measures externally transferred torque in real-time and, thus, enables both position- and torque-controlled modes of operation, allowing implementation of both robot-in-charge and user-in-charge exercise paradigms.

Hsieh et al., in 2017 in [

73], proposed a shoulder exoskeleton with linear SEAs to obtain accurate force and impedance control at the exoskeleton–limb interface. A variant of SEA is represented by SEAC [

75], series of elastic actuators with clutch, in which a mechanical clutch automatically disengages the transmission when needed. This mechanical solution improves actuator transparency and safety and guarantees the desired assistance in terms of both timing and torque magnitude.

Other very promising actuators for exoskeletons belong to the class of Variable Stiffness Actuators (VSAs), which is a sub-class of Variable Impedance Actuators (VIAs). VSAs are inspired by the human capability to adapt the joint stiffness to the external conditions and perturbations and can vary their mechanical impedance directly at the physical level as the natural musculo-skeletal system does. These actuators may change the stiffness without the need of an active control capable to simulate different stiffness values. Safety, energy-efficiency and resilience are the main advantages associated with the use of VSAs.

Schrade et al., in [

76] developed a lower-limb exoskeleton, the VariLeg, with a variable mechanical stiffness actuation (VSA) unit that drives the knee joint. This solution allows a low energetic cost of transport of human walking. Additionally, adjustable compliance is also expected to increase efficiency, safety and stability of human–robot interaction in gait rehabilitation. The authors also demonstrated that such adaptable compliance provides advantages to cope with uneven terrain or external perturbations and increases the achievable gait speed by allowing more dynamic walking.

Liu et al., in [

77], tested the stability robustness test of a variable stiffness actuator (VSA) programmed with the Gain Scheduling-based Variable Impedance Control (GSVIC). The proposed control system follows the paradigm of the variable impedance task in accordance with human intention. Cestari et al., in [

78], presented an actuator with Adjustable Rigidity and Embedded force Sensor (ARES) that is conceived as a force-controlled variable impedance actuator. This actuator not only provides elasticity on the joint but also allows intrinsically performing a measure of the torque exerted by the joint. Some authors have developed exoskeletons in which both SEAs and VSAs are present. Baser et al., in [

70], presented the lower limb exoskeleton named BioComEx with one variable stiffness actuator (VSA) for the ankle and two series elastic actuators (SEA) for knee and hip joints.

Recently, another solution of compliant actuator was developed: the Parallel Elastic Actuators (PEAs). Penzlin et al., in 2021 in [

79], investigated the parallel elastic actuators (PEA) and postulated that the efficiency of such drives in cyclical motion tasks, such as gait, can be increased by employing an elasticity acting in parallel to the actuator. Toxiri et al., in [

80], proposed PEAs for assisting workers in carrying and lifting weights while reducing the actuator’s peak electrical torque and accelerating its reaction.

Another SEA variation is the Magneto-Rheological Series Elastic Actuator (MRSEA), which takes the advantages of both SEA and MR brake. Chen et al., in [

71], presented a MRSEA designed for the knee joints of a lower extremity exoskeleton. The actuator, by reducing the overall mechanical impedance of the exoskeleton, filters out unwanted collisions and, furthermore, improves the system energy efficiency by providing large controllable braking torque with low power.

A particular actuation solution that deserves to be mentioned is that proposed by Han et al., in [

74]. Han presented a multimodal actuator, based on a motor paired with a clutch (at the center) and brakes acting in parallel, which allow the output to be actuated or passive. The multimodal actuator is capable of operating a joint with different modes, e.g., a series elastic mode can be used for fast running by storing energy in the spring, or a stiff position actuated mode allows a precise joint control when carrying large payloads.

4.1.2. Motion Transmission

The analysis of exoskeleton mechanical transmissions (

Figure 12) revealed that cables are the most adopted solution. Using the cable transmission system results in a significant reduction in the exoskeleton’s weight and in the required torque at the joint level. The cable-driven exoskeletons fall in the so-called flexible exoskeletons category, which has more natural human–machine interaction. At present, among cable transmissions for exoskeletons, Bowden cables are the most common. Bowden cables’ working principle is the transmission of the motor driving torque to the joints through cables, winding wheels and pulleys [

81].

Using Bowden cable transmissions, often the motor and transmission are located to the wearer’s back (in particular for LLE) to improve the mass distribution. Very often Bowden cables are used in conjunction with SEAs [

52,

69,

82,

83,

84,

85], as the spring element is connected with the Bowden cable, obtaining the so-called serial elastic actuator Bowden cable drive. Agarwal et al., in 2017 in [

49], presented a hand exoskeleton to move the thumb featured by a large range of motion (RoM), based on a series elastic actuation with Bowden cable, allowing for bidirectional torque control of each thumb joint individually.

In [

69], Aguirre-Ollinger and Yu investigated a novel force control method for a SEA-driven lower-limb assistive exoskeleton and the SEA is powered by a DC brushless motor, which transmits force to the Bowden cables via the springs. The regulation of the springs deflection is used for the force control, and the Bowden cables exert torque on the exoskeleton joint by means of a pulley and a fixed-axis rotary coupling. An innovative use of cable transmission is presented by Chen et al., in [

86], in which two identical SEAs are connected through a novel cable-driven differential that couples the elbow flexion/extension and the forearm supination/pronation joints, thus, allowing actuator load sharing, structural member size reduction and a compact design.

In some cases, the solution named Quasi-Direct Drive (QDD) actuation is particularly suitable [

87]. QDD actuation (also known as proprioceptive actuation) is based on a high torque density motor coupled with a low gear ratio transmission and allows high bandwidth and high back-drivability for a wide variety of human activities. Some authors developed solutions based on the reduction in the number of actuators, such as Ko et al., in [

54]. In that lower-limb exoskeleton (LLE), with an actuator, through wires and a differential gear mechanism simultaneously, both legs were driven.

4.1.3. Hydraulic and Electro-Hydraulic Actuation

The main advantages of hydraulic actuation are its inherently compliancy, low joint inertia and high loads, while the main drawbacks are related with the resulting in non-portable, heavy and difficult to manipulate exoskeletons in addition to the risk of hydraulic fluid leak. Successful implementations of these actuators are mainly in the LLE systems, for which the load capability is one of the most important requirements. As well as for electric actuators, variable stiffness, magnetorheological clutches and cable transmission concepts are also adopted for hydraulic transmission. Zhu et al., in [

88], described the design and experimental testing of a unidirectional variable stiffness hydraulic actuator applied to an exoskeletal knee, in which a variable ratio lever mechanism with linear elastic element was used to achieve the adjustable passive compliance of the joint.

Long et al., in [

89], presented a LLE with a pump-based hydraulic actuation system with unidirectional cylinder with embedded springs on the cylinder rod to make the hydraulic actuation system compact and lightweight. The springs help to control the leg in the swing phase without consuming energy of hydraulic system. Khazoom et al., in [

90], proposed a LLE system, which combines delocalized magnetorheological (MR) clutches with a hydrostatic transmission using low-friction rolling diaphragms to distribute power around the body to provide transparent and yet powerful multifunctional exoskeleton assistance.

Lu et al., in [

91], presented a LLE with a drive system based on hydraulic actuators and tendons drive for each joint, distinguished by high power and low inertia. The proximal end of tendon connects each rod of the cylinder and the distal end of tendon is fixed on the joint. The tendon can move freely in the sheath. The tendon is pulled by the hydraulic cylinder to produce the flexion and the extension in the sagittal plane.

Often, an electro-hydraulic drive is the preferred choice. Staman et al., in [

92], presented the design, control and evaluation of LLE exoskeleton for gait restoration developed with PREHydrA (passive return electro-hydrostatic actuator). The goal was to develop a high force density actuator, using remote actuation to relocate mass to favorable locations to improve the wearable aspect. The PREHydrA concept was shown to produce high output forces over a range of frequencies relevant to wearable robotics.

The design of an electro-hydraulic actuator (EHA), which has both the hydraulic and electric advantages, was treated by Lee et al., in [

93]. The EHA system consists of a hydraulic bidirectional pump, a motor, a hydraulic cylinder and the valves obtained in a manifold. The motor attached to the pump allows the hydraulic actuator position and speed control. This solution provides high level of power, but the hydraulic circuit simplicity reduces manufacturing costs and allows for easy leakage manage.

4.1.4. Pneumatic Actuation

Pneumatic actuators have intrinsic compliance and a high power-to-weight ratio but limited forces and torques values—features that make them suitable for exoskeleton actuation when high forces or torques are not required. As confirmed by the cross analysis synthesized in

Table A2, PAM is the most widely adopted pneumatic actuator in exoskeletons. PAM is formed by a not expandable double-helix-braided shell wrapped around a rubber tube. When the tube is inflated with pressurized air, this causes a PAM contraction in the longitudinal direction, and, when it is deflated, it returns to its original shape; therefore, it is an alternative actuator.

Compared to electric motors, PAMs have several advantages, e.g., inherent compliance, low cost, a high power-to-weight ratio and compactness. In addition to these advantages, the PAM operation is characterized by hysteresis and significant nonlinearity; therefore, appropriate control strategies must be developed to improve PAM performance (e.g., the accuracy of joint trajectory tracking) and to obtain effective actuation solutions for soft exoskeletons. Furthermore, PAMs are unidirectional, and thus to obtain bilateral rotations, they must be used in pairs, i.e., two PAMs are mounted in an antagonistic configuration.

The PAM control problem was addressed by Cao et al., in [

94], who used an artificial neural network, an echo state network [

95] to approximate the dynamics of a PAM-driven exoskeleton with a nonlinear autoregressive exogenous model to forecast its behaviors. The same authors, Cao and Huang in [

96], used nonlinear model predictive control (NMPC) and an extension of the echo state network called an echo state Gaussian process (ESGP) to design a tracking controller for a PAM-driven lower limb exoskeleton. Zhao and Song, in [

97], introduce a novel proxy-based sliding mode control (PSMC) to obtain an accurate trajectory tracking.

A PAM variant is the Pleated PAM (PPAM), developed at Vrije University Brussels. Beyl et al., in [

98], for a LLE used PPAMs with a novel design that allows for a higher torque range in a larger range of motion. Cable-driven transmission, as well as with electric actuators, is also used with PAMs. Chen et al., in [

99], presented the design, dynamic modeling and motion control of a cable-driven ULE actuated by PAMs. In order to perform passive rehabilitation exercises, dynamic models were developed, and an adaptive fuzzy sliding mode control was designed for the rehabilitation trajectory control.

Hybrid solutions with pneumatic actuators acting in parallel with electric ones have been proposed. Chakarov et al., in [

100], presented an exoskeleton with hybrid electric-pneumatic actuation, in which the pneumatic drive takes care of the initial reaction of the force, and the electric drive complements the pneumatic drive. Aguilar-Sierra et al., in [

101], described a LLE in which two types of actuators are applied: DC motors with the harmonic drive and PAMs. The hybrid actuation overcomes the short-comings of the two kinds of actuators, e.g., low control accuracy and modeling difficult due to the pneumatic artificial muscle, compactness and structural flexibility of DC motors.

Other types of soft-actuators used in exoskeletons have been developed and tested. Zhang et al., in [

102], introduced the design of a vacuum-actuated rotary actuator applied to a wearable soft knee exoskeleton that aids active knee motions during walking. Oguntosin et al., in [

103], demonstrated the design, production and functional properties of an Exoskeleton Actuated by the Soft Modules (EAsoftM).

The soft modules, developed to be attached to the joints, are made of polyethylene and have multi-cells with one end glued together by thermal adhesion. ABS frames were used to maintain the structure of each cell when deflating the modules by applying negative pressure. The inflatable actuator was pressurized by pneumatic actuators through silicon tubes, and, as the individual cells start to push against each other, the whole module produces the torque in the fan-shaped manner as a function of pressure.

4.2. Sensors

As schematized in the block diagram of

Figure 1, sensors are an indispensable element in an exoskeleton, as they allow detecting information from the environment (that includes the user) with which the robot interacts. These collected data are essential to control the exoskeleton. Different types of information may be necessary depending on various aspects, such as the type of exoskeleton (e.g., depending on the anatomical district to which it is intended), the type of control and the mode of operation.

Consequently, many types of sensors can be used, such as force, torque, pressure, EMGs, EEGS and bending sensors, IMU, cameras and encoders to measure physical quantities, such as positions, displacements, rotations, forces, torques, accelerations and muscle and neuronal activations. A cross analysis of the paper distribution of sensor types vs. anatomical district was conducted, and

Table A4 collects the paper classification, while

Figure 25 and

Figure 26 present, in a synthetic way, the results.

As already highlighted by the prospective review, the exoskeletons for the lower limbs are the most widely investigated; consequently, the distribution of the sensors according to the anatomical district also shows the highest concentration of sensors related to the LLE. For this type of exoskeleton, in particular those of the assistive and rehabilitative type, a topic of great importance is gait analysis to recognize the different phases and consequently check, in real time, the contribution provided by the exoskeleton and keeping synchronization with human movements. For this purpose, force, torque and pressure sensors as well as IMU, EMG and encoders are the most used, and very often they are used in a multi-sensor configuration [

20].

The sensing of human intention motion is a common concern to many exoskeletons, not only LLE but also ULE or hand exoskeletons. In recent decades, the use of biosensors has become increasingly widespread. These sensors detect biological signals, such as muscular electromyographic, mechanomiographic and electroencephalographic signals. EMG signals have been widely investigated for real-time motion intention recognition from muscle potential activations with sophisticated control algorithms that are sometimes based on machine learning classification methods [

104]. Mirroring techniques are used in hemi-paretic subjects to favor a faster neuro-motor recovery [

19].

The cross analysis highlights that the dynamic sensors (pressure, force, torque sensors and IMU) are, as a whole, the most used in hand exoskeletons and ULE. The detection of human intention can also be performed by detecting the neuronal activity of the brain through EEG, and the application of this technique for the control of exoskeletons, particularly LLE, was investigated, but there are still many limitations due to the complexity of brain signals. The position feedback (e.g., with linear or rotational encoders) is essential in the functioning with control in force or torque of the compliant actuators and devices that are becoming increasingly widespread for use in robots interacting with humans, SEAs, PEAs, VSAs and MR brakes.

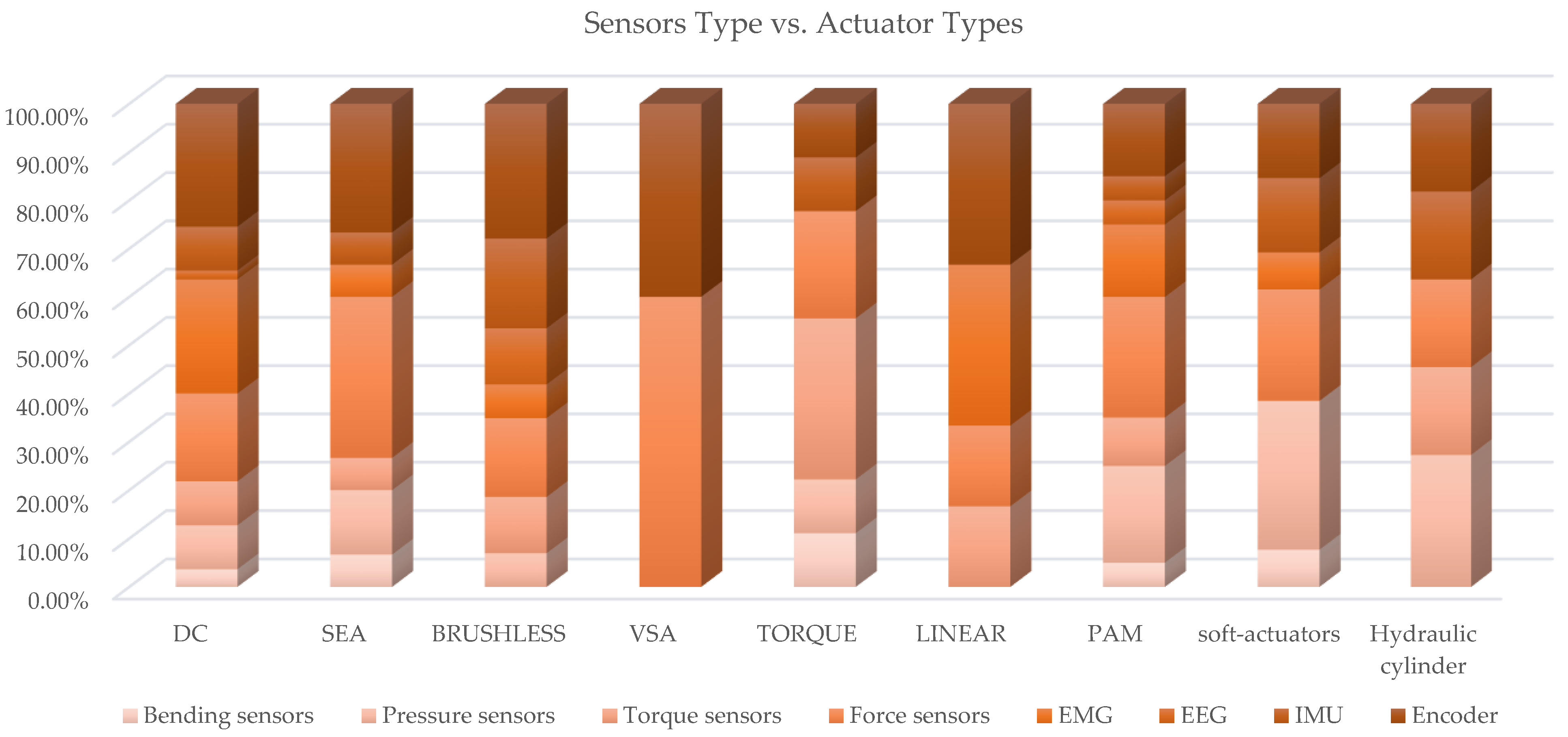

Further cross analysis of sensors vs. actuator types and vs. power source was carried out.

Table A5 collects the paper classification, while

Figure 27 and

Figure 28 present, in a synthetic way, the results. The following considerations emerge from the observation of

Figure 27: For exoskeletons with DC, SEA and Brushless actuators, encoder are the most used sensors (with percentages of around 26%); pressure sensors are particularly used when fluidic actuators are present (as is predictable). Force sensors are highly used with SEAs, VSAs and torque motors; torque sensors are used particularly in devices with torque actuators and linear motors.

Bending sensors are somewhat used when soft-actuators and torque motors are present. IMUs are mainly used in exoskeletons with hydraulic cylinders and brushless motors. Analyzing

Figure 27, it emerges that, in exoskeletons with electric drives, encoder sensors are predominant, followed by force sensors, EMGs, torque sensor and IMU in that order; with pneumatic power sources, pressure sensors are the most used, followed by force sensors, encoders and EMGs; even with hydraulic actuation, a similar distribution is observed, with the difference that, in this case, IMUs also have a significant weight.

The following paragraphs analyze, in detail, the main class of sensors used in exoskeletons, and we attempt to detect the trends for the sensing issue in exoskeletons.

4.2.1. Bending Sensors

Bending sensors are adopted to measure the characteristics of a deflecting element from a neutral configuration. The main objective of bending sensors is to detect the magnitude and orientation of the bending force produced by a deflecting element; thus, these sensors are used for bending quantification and, indirectly, to measure other physical quantities [

43,

105], such as pressure and stress, in the exoskeleton and in the interaction with external environment. These elements are particularly interesting in wearable electronic and electromechanical devices, such as active exoskeletons, or to directly measure human motion because they can work in different positions with respect to the human body and are tolerant to different wearing configurations.

These are very promising for applications because of their flexibility to be used in different positions and angles on the exoskeleton and can measure the direct bending or the bending due to pressure from pressing external object. They can measure also a mix of joint movements, such as in finger movements of glove-exoskeletons [

106]. A bending sensor is composed of an elastic part and a rigid part. The elastic part is used to restore the deflection of the deflecting element, such as a human finger in the case of finger-exoskeletons [

107].

The rigid part of the bending sensor is surrounded by an elastic material. This material can be a rigid or semi-rigid tube, in this case, the bending sensor will be referred as a “Tubular Active Bending Sensor”, or it can be made of a rubber film, such as a “Rubber Active Bending Sensor”. In artificial pneumatic muscles [

108], the elasticity of a rubber film can be produced using air pressure. For non-rigid materials, there are several techniques used to deform them: torsion, compression, shear and stretching [

62]. The rigid part of a bending sensor is used to transmit the characteristic quantities to the central processing unit (CPU), which directly measures the quantity desired.

It also can be directly connected to an actuation element, which can be a motor or a valve in case of exoskeleton applications. Some bending sensors have been developed for wearable applications and for special sensors for picking and grasping objects. The most adopted technologies are piezoeletric, resistive, optical and capacitive [

18]. Piezoelectric effects allow the generation of an electric energy when a piezoelectric element is deformed. Different authors focused their attention on the relation between output voltage and bending curvature.

These sensors can be adopted, i.e., as surface sensors integrated in low flexion actuators. Other piezoelectric sensors considered also the effect of bending speed to improve the sensing accuracy and precision. In this last case, it is possible to measure high bending motions, i.e., in glove exoskeletons. A thick resistive material is coated onto a thicker plastic insulating substrate to create resistive bending sensors [

58]. The resistive strip is screen printed with a unique carbon ink on the flexible substrate. With the deflection caused by an applied external force, the resistance value of the ink varies. They can be used as electronic goniometers on body joints [

56] to create goniometric clothes for assessing the relative configurations of human body segments.

Optical-fiber bending sensors have benefits over other electrical sensors in terms of small size, anti-electromagnetic interference, corrosion resistance, high sensitivity and cheap maintenance costs; hence, they are frequently utilized in bending measurement. In these devices, a light is emitted from a source and passed through an optical fiber to reach a light-sensitive element. The light passing through the fiber is altered by deflection of the fiber; thus, according to the measuring methodologies used, the optical fiber bending sensor used in exoskeletons may be split into three categories: intensity modulation, wavelength modulation and frequency modulation.

Capacitive bending sensors are based on the relative displacement of two adjacent surfaces that constitute a capacitor. As their distance varies, the capacitance, which is related to the bending, also varies. The variation of the capacitance is proportional to the bending displacement up to a critical range, depending on the geometry of the sensor and on the material used. Beyond this range, the force required to produce a given displacement becomes higher due to increasing flexion and thus displacing contacts. In general, it is used as a simple bending sensor or in touch sensors for human-environment interaction or exoskeleton environment interaction.

4.2.2. Dynamic Sensors

Dynamic sensors, used in exoskeletons, can be divided into four major macro-categories: Pressure Sensors, Force Sensors, Torque Sensors and IMUs, depending on the physical quantity they measure. These sensors are particularly suitable to measure interaction actions between exoskeleton and human limbs. Pressure sensors are adopted in exoskeletons that use fluidic actuators or other parts, such as PAMs or, more in general, soft actuators. The measure of fluidic pressure is indirectly related with other dynamical variables, such as force/torque interaction with external environment and with the subject wearing the exoskeleton.

When high band signals are important, i.e., in real time force control, piezoelectric sensors are usually preferred. Pressure sensors can also be used inside soft-sensors, as in the work by Wang et al. [

109], where a wearable, low-cost and compact soft sensor system for direct force measurement in a hip exoskeleton is presented. The sensor is based on a soft pneumatic chamber, in which the dynamic interaction forces are converted into the air pressure changes and measured though a differential air pressure sensor. Different materials and shapes of the chamber were compared to provide useful guidelines in the design of soft sensors.

Force sensors allow the direct measurement of the force exerted by the user at the interface. Force sensors are also used to validate devices or for performance estimation. Usually force-sensors used in this context are load cells. In the work by Kazeminasab et al. [

110], load cells are used for the validation of a hand exoskeleton, i.e., for force sensing at the fingertip. The exoskeleton uses SMA actuators and an under-actuated tendon-driven mechanism. The device is capable of exerting extremely high force levels to grasp objects; it can provide 45 N gripping force.

Hamaya et al., in [

111], used force sensors to measure the user–robot interaction in a two-degree-of-freedom upper-limb soft exoskeleton with four PAMs. Choi et al., in [

112], presented a compact force sensor system with two FSR (force-sensitive resistors) for an assistive LLE sensors. The system measures the assistance force, i.e., delivered force and power of the exoskeleton for motion control and taking urgent safety action. A very peculiar application of force sensors was proposed by Zhang et al., in [

113], to develop a spasm sensor to detect joint spasm force with the principle of force detection and identify the spasm type to be applied in hand exoskeleton for rehabilitation.

Torque sensors are mainly used in LLE. Chen et al., in [

114], developed a LLE in which each joint is fitted with an absolute encoder, incremental encoder and torque sensor that record the joint angle, angular velocity and torque, respectively, and he proposed a method to predict the human motion intention while walking based on an estimation of the active joint torque of human lower limbs.

Yu et al., in [

87], presented a hip exoskeleton composed of a waist frame, two actuators, tow torque sensors and two thigh braces, based on a custom quasi-direct drive actuation (i.e., a high torque density motor with a low ratio gear). An unusual way to detect the torque resulting at the interface user-exoskeleton, and which is presented in various studies, is the use of a SEA actuator as a sensor. Jarrett et Mc Daid in [

115], presented a model for an elastomer-based series elastic actuator (eSEA) and tested its feasibility to provide torque sensing as a haptic interface for soft, comfortable HRI in exoskeletons.

As can be seen in

Figure 27, IMU sensors are almost exclusively used for LLE; in fact, one of their main functions is to help in the complex task of studying the gait phases. Susanto et al., in [

116], used an IMU sensor to recognize the pitch angle generated from the knee joint while the user of a LLE walks as useful information about the walking gait cycle. Often, multiple sensors are used together; an example is given; however, there are many works in which this has been found.

Kim et al., in [

105], presented the development of a modular knee exoskeleton system that supports the knee joints of hemiplegic patients. In order to determine the user’s intention, force-sensitive resistors (FSRs) in the user’s insole, a torque sensor on the robot knee joint, and an encoder in the motor are used. In multi-sensor systems, a need that may arise is sensor information fusion.

Qi et al., in [

117], proposed an improved greedy reduction algorithm; the data from seventeen sensors in a LLE were collected, and the set theory and the improved greedy algorithm were used to reduce and select the suitable set of sensors. Sun et al., in [

118], presented a sensor reduction technique for force/torque sensors utilizing a Kalman filter-based sensor fusion system.

4.2.3. Electromyographic (EMG) Sensors

Electromyography (EMG) is a method of assessing and recording the electrical activity of skeletal muscles. When muscle cells are electrically or neurologically excited, this technique may detect the electric potential emitted by these cells. The signals can be studied to look for anomalies, levels of activation, or recruitment orders as well as to associate it with the kinematics of the generated movement. Two main approaches can be adopted: needle EMG, where a needle connected with an electrode is inserted into the muscle, and surface EMG, where an electrode is attached to the skin in the proximity of the muscle.

In exoskeletons, thsi technique can be adopted to command the motion of the device to combine the motions of the subject and the exoskeleton in an active-assisted approach or to simply evaluate the activation pattern of the subject during the realization of the motion. Needle EMG is an invasive practice and must be performed by experienced medical personnel trained in the use of this procedure, while surface EMG is a non-medical method and, therefore, can be easily performed in various contexts. Furthermore, as the exoskeleton is a wearable system that can be removed from the human subject, there are no needle EMG applications in combination with exoskeletons in the literature.

Needle EMG could be used in the case of prosthesis; although, in these situations, a subcutaneous and fixed electrode innervation is conceivable, avoiding also, in this case, the insertion of a needle through the skin. On the other hand, surface EMG is subjected to various artifacts associated with skin slippage, electrical resistance of the skin and its variability with atmospheric conditions and hydration level. Therefore, needle EMG remains a method for accurate neurological examinations where high measurement accuracy is strictly required. In some of the analyzed works [

119,

120,

121,

122,

123], EMG was used to collect data on the activation pattern of a subject wearing an exoskeleton.

In the works by Moon et al. [

124] and Chandrapal et al. [

125], EMG was used for intention detection for a single leg knee exoskeleton, and a similar approach was used in the works by Kiguchi et al. [

126] and Rosen et al. [

127] for an elbow exoskeleton. In the paper by Aguilar-Sierra et al. [

101], the EMG signal of a lower limb was used for command of a lower limb exoskeleton. In Li et al. [

128], an EMG signal of the upper limb was analyzed in real-time and adopted in the controller of a lower limb exoskeleton to adjust to the height and width of stairs. In Fleischer et al. [

129], the EMG signal was used in two different real-time controlled exoskeletons, a single knee and a hand exoskeleton.

4.2.4. Electroencephalographic (EEG) Sensors

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a representation of the temporal evolution of the electric fields measured on the skull’s surface. The spontaneous oscillations of membrane potentials at the level of brain synapses are represented by the EEG signal, which is generated by neurons on the cortical surface. The EEG can be used to assess spontaneous or induced brain electrical activity in both normal and diseased settings. EEG recordings come in a variety of shapes and sizes, depending on the scenario.

The location of the generators (source) and an electric dipole, which, in turn, depends on the directionality of the ionic fluxes, affects the EEG signal recorded at the surface. EEG signal has only some correlation with the electric brain activity. Furthermore, while the cerebral cortex can create and modulate cerebral electrical activity on its own, subcortical structures, particularly the thalamus, play a significant role in the creation and regulation of this activity. As mentioned, generally EEG is measured on the scalp. EEG. Electrodes, signal amplification and replication systems are crucial components.

Electrodes come in a variety of shapes and sizes (scalp-fixed, headset-fixed and hypodermic needle-fixed). EEG investigations are multichannel with two electrodes attached to each channel. Different electrodes must be positioned in standard positions on the skull’s skin. Preliminaries uses of EEG have been devoted to study electric field features [

130]. Different authors measured EEG signals to predict motion intention, thus, realizing a Brain Computer Interface (BCI) to command an exoskeleton [

128] for healthy or pathological subjects eventually in combination with other techniques, such as EMG or functional electrical stimulation (FES) [

131].

As already seen, the EEG signal can be very different between subjects. This difference is further increased in the case where a subject has a pathology that affects the functionality of the brain, such as stroke, Parkinson’s disease, severe acquired brain injury etc. Therefore, any use of the EEG signal must be highly customized and must include a learning period. In rapidly evolving diseases, such as acute and subacute strokes, EEG features must be recalibrated at regular time intervals.

4.2.5. Cameras and Optical Vision System

RGB cameras, infrared cameras, wide angle cameras and three-dimensional cameras, such as stereo vision cameras and depth cameras, are examples of video sensors that may be used to collect data. Depth cameras are made up of infrared sensors and an RGB camera, with the data received by the second camera being represented in three-dimensional space using mathematical models based on infrared ray emission and detection.

Stereovision cameras, based on the stereovision principle, often require two or more sensors to capture three-dimensional information of a subject through the triangulation process. Thermal cameras and other types of equipment can be used to assess peripheral vascular function during mobility. The only application of video cameras observed in the literature for use with exoskeletons consists of systems to validate the motion realized by these devices once worn or to generate joint motion patterns to be provided to exoskeletons by observing the natural motion of human subjects in the absence of exoskeletons.

In the work of Pan et al. [

132], a six-camera infrared motion capture system was used to capture the motion of healthy and pathological subjects, which was used to realize command motion profile or to project the rehabilitation therapy. In the work by Jones et al. [

133], a two-camera setup employing high-resolution, monochrome CCD cameras was used to measure exoskeleton joint angles for comparison with encoder-measured angles. Markers were attached to the exoskeleton to record movement. In the work by Chen et al. [

134], the markers were covered with ultraviolet-sensitive fluorescent paint and illuminated with a UV light source.

4.2.6. Encoders

The angular position or motion of a shaft or axle is converted to analog or digital output signals by a rotary encoder, also known as a shaft encoder. A shaft encoder outputs rotation angle signals in the form of pulses, which are then fed into a signal conditioning system that converts the signal to a more usable form. As with many motors and similar devices, there is often some play in the shaft between its two ends. This makes it difficult to measure the absolute position of this device using only analog inputs, such as voltage or potentiometers. This requires the use of digital inputs or software-based subsystems for measurement and feedback control. The angular position of a shaft encoder can be measured by an output test gauges that monitors the torque on an axis on a stationary point and indicates what angle corresponds to what amount of rotation in degrees.

Absolute [

135] and incremental rotary encoders are the two most common variants. An absolute encoder is an angle transducer since its output indicates the current shaft position. An incremental encoder’s output offers information on the shaft’s motion, which is often processed into information, such as position, speed and distance. In exoskeletons, they are used in the proximity of a rotary motor [

72] or in a rotary joint of the exoskeleton [

119]. The first solution is adopted in low cost approaches and when the transmission between motor and joint is sufficiently rigid.

The second solution is adopted to accurately monitor the relative motion of two adjacent body segments around a human joint or the relative motion of two adjacent exoskeleton segments around an exoskeleton joint. In complex solutions, encoders are fused [

124] with other sensors to realize a whole information acquisition system. When the structure of the exoskeleton is sufficiently rigid, encoders can be used to measure anticipatory movements and to forecast movement intention [

136].

Sometimes, encoders are also adopted in elastic structures [

52]. In general, mechanical, optical and magnetic are the most widely used technologies. A mechanical encoder can be rotary or linear. In most cases, applications in exoskeletons involve rotary encoders. In this type of system, there is a disk, normally metallic or otherwise rigid, with concentric rings rotating integrally with the shaft. The opening and closing of cavities produces an encoding, according to a binary code, of the relative position between a fixed reference and a mobile one. It is possible, under certain design conditions, to realize multi-turn encoders in which the position encoding is relative to a sequence of rotary movements that take place on a trajectory greater than 360 degrees.

An optical encoder comprises a shaft attached to a circular disc with one or more tracks of transparent and opaque sections that alternate. Each track has a light source and an optical sensor on opposite sides. The light sensor releases a series of pulses as the shaft rotates, interrupting the light source with the pattern on the disc. This output signal can be used with digital circuitry directly. Due to the number of output pulses, each rotation of the disc is known, and the number of output pulses per second may be translated directly to the shaft’s rotational speed.

Magnetic encoders exploit the magnetic field produced by a source located on the shaft, and, in this case, they are called on-axis, or on the hub. In the other case, they are called off-axis. Their advantage lies in the ability to operate even in disturbed contexts. In the case of potential magnetic interference, there are sensors that are properly shielded and, therefore, insensitive to environmental magnetic conditions.

4.2.7. Other Sensors

A wide range of different other types of sensors are used within exoskeletons as sources of information to correct system motion in real time via a controller, to evaluate the motion characteristics of a subject wearing an exoskeleton [

43,

45,

60], to command/modulate the realized motion or simply to identify a more or less natural motion that can be used as a set-point for the exoskeleton itself.

In the work by Crea et al. [

137], capacitive sensors in orthopedic cuffs on the shanks were used to control a robotic hip orthosis. Sometimes, an alternative type of mechanical transmission used involves the use of different sensors than usual. For example, in the work by Ismail et al. [

138], an infrared sensor was used as limit switch within a mechanism based on a high precision lead screw, which moved a tendon cable able to transfer the movement from the actuator to the interface between human and exoskeleton.

Sensors can be placed near the actuator that makes a standard movement, on a joint that allows fairly simple relative movements between body segments or directly on the body segments measuring the absolute movement can also be complex since this is produced by a multiplicity of actuators. Hybrid sensor network positioning is present in the literature [

74]. For example, in the works by Rudd et al. [

139] and by Ertas et al. [

121], the authors presented low cost exoskeleton solutions exploiting a simple potentiometer integral with the driven shaft of a gearbox downstream of a simple DC motor. In the paper by Hunt et al. [

140], piezo-resistive sensors were inserted in a theoretic project of a shoulder exoskeleton.

The accuracy and precision requested for this application is limited; thus, simple technologies, such as potentiometers [

88,

141,

142], are often adopted as well as other alternative solutions, such as Hall effect sensors [

143]. During walking, it can be interesting to know in which gait phase of the subject is at that moment to evaluate the naturalness of the movement and also to provide feedback to a possible control system that can make corrections. To obtain this information, insoles are often used and placed under the sole of the foot; they essentially use pressure or deformation sensors, as is the case in the work of Wang et al. [

144].

Some authors designed innovative soles [

42] for this application. In these exoskeletons, it is common to obtain information from the joint position and/or torque and also insole sensors [

91,

145] to feed the controller. When hydraulic actuators are used [

90], it is possible to have information on the mechanical actions exchanged between the human subject and the exoskeleton simply by measuring the fluid pressure even in the proximity of the actuator, given the low compressibility of the fluid used for the transfer of mechanical energy inside the transmission system.

There are also hybrid solutions in the literature [

89,

146,

147,

148] that use various types of sensors even under conditions of hydraulic actions [

149], and sometimes authors speak explicitly about the sensor fusion approach [

126,

150]. An interesting solution, even if it presents a low level of accuracy and precision, consists of measuring the electricity absorbed by a motor of an exoskeleton in terms of the current and voltage [

151] in order to know the mechanical power delivered by the motor in terms of the torque and speed due to the knowledge of the electromechanical characteristics of the motor itself.

The most complex sensing system is one that allows knowledge of the movement of the distal elements [

152] of a limb to provide haptic interface input for the purpose of interaction with a real, virtual or distant environment. To simplify this sensing process, some authors [

115], who noted the fact that the exoskeleton is integral to the body segments and that its joints have centers of instantaneous rotation quite coincident with the relative centers between the body segments, proposed to measure the motor torques of all the actuators to combine them to, thus, obtain an estimate of all the forces acting on the exoskeleton.

A similar solution adopts a kinematic approach to identify gait phase only with joint sensors [

153]. It can be interesting, for various reasons to learn about the behavior of the muscles of the subject wearing the exoskeleton. We have seen that the commonly used technique is EMG, which measures the electrical activation of muscles. An alternative technique is represented by the Force MyoGraphy (FMG) [

154], which measures the change of muscle stiffness in a non-invasive way through sensor bands worn during the movement produced precisely by these changes in stiffness.

As it is possible to devise designs of underactuated exoskeletons that are compliant with the structure of the human body, similarly, some authors used flexural sensors, for example, through the use of piezo-resistive materials [

112] to identify forces exchanged between the subject and the exoskeleton or by building new non-contact optical sensors [

155] that measure the forces exchanged by analyzing the optical deflection of a light beam emitted from a source. Other low-cost approaches consist of developing sensorless solutions [

73] that exploit classical Series Elastic Actuators (SEAs), which allow the adaptation between exoskeleton and human subject by incorporating within it passive elements, such as springs, or even active ones, for example magnetorheological SEAs [

71].

In these cases, sometimes calibration is performed via external sensors only offline, such as in the work by Kim et al. [

156] with an isokinetic dynamometer. An alternative solution [