Better Data from AI Users: A Field Experiment on the Impacts of Robot Self-Disclosure on the Utterance of Child Users in Home Environment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Self-Disclosure

2.2. Eliciting Self-Disclosure from Users

2.2.1. Limitations of Prior Studies and Motivations for the Current Study

2.2.2. Eliciting Self-Disclosure in Clinical and Counseling Psychology

2.2.3. Hypothesis of Robot Self-Disclosure Strategies

2.3. Multi-Robot Systems

2.3.1. Theoretical and Practical Perspectives of Introducing Multi-Robot Systems

2.3.2. Hypothesis of Multi-Robot Systems

3. Methods

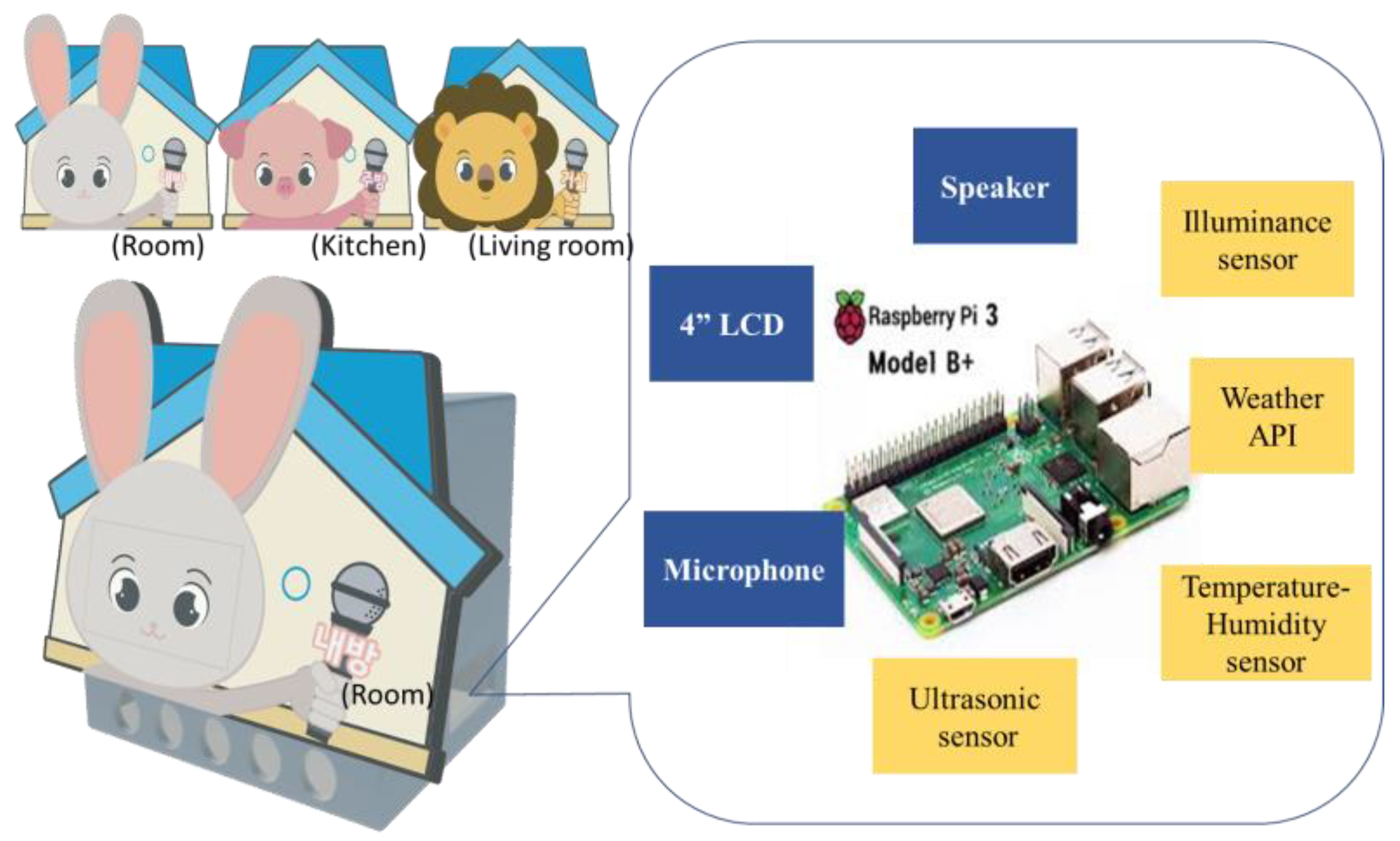

3.1. Prototype

- The Home Companion-bot continuously performs ambient sensing for temperature, humidity, illumination, and weather;

- The Home Companion-bot recognizes the approaching user and greets them with voice;

- The Home Companion-bot performs self-disclosure to the user based on the detected data. Explanations of stimuli for self-disclosure are explained in detail later in Section 3.5;

- The Home Companion-bot listens to the user’s response to its self-disclosure and records it. Then, the Home Companion-bot responds to it.

Companion-bot’s utterance: Hi, Mary! You look a little stuffy. I think it’s because the sky outside the window is cloudy and dark. Mary, how well do you see outside the window now?

Participant’s utterance: I can’t see well out of the window, but my mood is not bad. I played with my friends earlier. So, to be honest, I feel good.

Companion-bot’s response: Oh really! Thank you for telling me, Mary.

3.2. Pilot Test

3.3. Experimental Design

3.4. Participants

3.5. Manipulation

3.6. Procedure

3.7. Measurements

4. Results

4.1. Manipulation Check

4.2. Measurement Validation

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

4.3.1. Speech Length

4.3.2. Depth

4.3.3. Amount

4.3.4. Summary of Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Research Implications

5.2. Limitations

5.3. Future work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Measurement Items | References |

|---|---|---|

| Disclosing Robot | Home Companion-bots seemed to talk about what they were going through. Home Companion-bots seemed to be talking about themselves. Home Companion-bots seemed to tell what happened to them. Home Companion-bots seemed to talk about what they were experiencing | No ref. |

| Involving User | Home Companion-bots seemed to be talking about what I was going through. Home Companion-bots seemed to be talking about me. Home Companion-bots seemed to tell me what happened to me. Home Companion-bots seemed to tell me what I experienced. | No ref. |

| Depth of User self-disclosure | When I talked with Home Companion-bots, I intimately and fully revealed myself. When I talked with Home Companion-bots, I disclosed intimate, personal things about myself. When I talked with Home Companion-bots, I intimately disclosed who I really am. | Ma and Leung, 2006 [108]; Gibbs, Ellison, and Heino, 2006 [109] |

| Amount of User self-disclosure | When I talked to Home Companion-bots, I talked a lot about my feelings and thoughts. When I was talking to Home Companion-bots, I spoke for a long time about me. When I talked to Home Companion-bots, I did not talk much about myself. (reverse coding) | Ma and Leung, 2006 [108]; Gibbs, Ellison, and Heino, 2006 [109] |

| Speech length | This was measured by converting the voice response of the child to text and counting the number of characters in the text. | Moon (2000) [101] |

References

- Ng, A. What Artificial Intelligence Can and Can’t Do Right Now. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016. Available online: https://hbr.org/2016/11/what-artificial-intelligence-can-and-cant-do-right-now (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Nielsen. (Smart) Speaking My Language: Despite Their Vast Capabilities, Smart Speakers Are All About the Music. Available online: https://www.nielsen.com/insights/2018/smart-speaking-my-language-despite-their-vast-capabilities-smart-speakers-all-about-the-music/ (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- El Ayadi, M.; Kamel, M.S.; Karray, F. Survey on speech emotion recognition: Features, classification schemes, and databases. Pattern Recognit. 2011, 44, 572–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ververidis, D.; Kotropoulos, C. Emotional speech recognition: Resources, features, and methods. Speech Commun. 2006, 48, 1162–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Yu, D.; Tashev, I. Speech emotion recognition using deep neural network and extreme learning machine. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, Singapore, 14–18 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L.; Moore, J.D.; Lai, C. Emotion recognition in spontaneous and acted dialogues. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction (ACII), Xi’an, China, 21–24 September 2015; pp. 698–704. [Google Scholar]

- Fayek, H.M.; Lech, M.; Cavedon, L. Evaluating deep learning architectures for speech emotion recognition. Neural Netw. 2017, 92, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, R.o.K. National Survey on Families; Ministry of Gender Equality and Family: Seoul, South Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rajalakshmi, J.; Thanasekaran, P. The effects and behaviours of home alone situation by latchkey children. Am. J. Nurs. Sci. 2015, 4, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomaguchi, K.M.; Milkie, M.A.; Bianchi, S.M. Time strains and psychological well-being: Do dual-earner mothers and fathers differ? J. Fam. Issues 2005, 26, 756–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Cho, M. The effects of after-school self-care on children’s development. J. Korean Soc. Child Welf. 2011, 36, 7–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatius, E.; Kokkonen, M. Factors contributing to verbal self-disclosure. Nord. Psychol. 2007, 59, 362–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, S.; Hess, S.A.; Petersen, D.A.; Hill, C.E. A qualitative analysis of client perceptions of the effects of helpful therapist self-disclosure in long-term therapy. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Society for Psychotherapy, Amelia Island, FL, USA, 19–23 June 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, M.S.; Berman, J.S. Is psychotherapy more effective when therapists disclose information about themselves? J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 69, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.E.; Knox, S. Self-disclosure. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 2001, 38, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henretty, J.R.; Levitt, H.M. The role of therapist self-disclosure in psychotherapy: A qualitative review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourard, S.M.; Lasakow, P. Some factors in self-disclosure. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1958, 56, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozby, P.C. Self-disclosure: A literature review. Psychol. Bull. 1973, 79, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R. The stress-buffering effect of self-disclosure on Facebook: An examination of stressful life events, social support, and mental health among college students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K. Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, C.E., Jr. The effects of counselor self-disclosure: A research review. Couns. Psychol. 1990, 18, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziv-Beiman, S. Therapist self-disclosure as an integrative intervention. J. Psychother. Integr. 2013, 23, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henretty, J.R.; Currier, J.M.; Berman, J.S.; Levitt, H.M. The impact of counselor self-disclosure on clients: A meta-analytic review of experimental and quasi-experimental research. J. Couns. Psychol. 2014, 61, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, H.M.; Minami, T.; Greenspan, S.B.; Puckett, J.A.; Henretty, J.R.; Reich, C.M.; Berman, J.S. How therapist self-disclosure relates to alliance and outcomes: A naturalistic study. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2016, 29, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, N.L.; Miller, L.C. Self-disclosure and liking: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joinson, A.N. Self-disclosure in computer-mediated communication: The role of self-awareness and visual anonymity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 31, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, K.; Derlega, V.J.; Mathews, A. Self-disclosure in personal relationships. Camb. Handb. Pers. Relatsh. 2006, 409, 427. [Google Scholar]

- Bazarova, N.N.; Choi, Y.H. Self-disclosure in social media: Extending the functional approach to disclosure motivations and characteristics on social network sites. J. Commun. 2014, 64, 635–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppel, E.K. Use of communication technologies in romantic relationships: Self-disclosure and the role of relationship development. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2015, 32, 667–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashian, N.; Jang, J.-w.; Shin, S.Y.; Dai, Y.; Walther, J.B. Self-disclosure and liking in computer-mediated communication. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeless, L.R. Self-disclosure and interpersonal solidarity: Measurement, validation, and relationships. Hum. Commun. Res. 1976, 3, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgas, J.P. Affective influences on self-disclosure: Mood effects on the intimacy and reciprocity of disclosing personal information. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, M.F. Opening up: Therapist self-disclosure in theory, research, and practice. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2012, 40, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourard, S.M. Self-Disclosure. An experimental Analysis of the Transparent Self; Wiley-Interscience: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Dindia, K.; Allen, M. Sex differences in self-disclosure: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Nachshon, O. Attachment styles and patterns of self-disclosure. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.N.; Hewstone, M.; Voci, A. Reducing explicit and implicit outgroup prejudice via direct and extended contact: The mediating role of self-disclosure and intergroup anxiety. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 93, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-T.; Noh, M.-J.; Koo, D.-M. Lonely people are no longer lonely on social networking sites: The mediating role of self-disclosure and social support. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2013, 16, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, A.; Kiesler, S.; Fussell, S.; Torrey, C. Comparing a computer agent with a humanoid robot. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Arlington, VA, USA, 10–12 March 2007; pp. 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, G.M.; Gratch, J.; King, A.; Morency, L.-P. It’s only a computer: Virtual humans increase willingness to disclose. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 37, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, M.D.; Roster, C.A.; Chen, Y. Revealing sensitive information in personal interviews: Is self-disclosure easier with humans or avatars and under what conditions? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 65, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumazaki, H.; Warren, Z.; Swanson, A.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Sarkar, N.; Ishiguro, H.; Mimura, M.; Minabe, Y. Can robotic systems promote self-disclosure in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder? A pilot study. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumm, J.; Mutlu, B. Human-robot proxemics: Physical and psychological distancing in human-robot interaction. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Lausanne, Switzerland, 6–9 March 2011; pp. 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Bethel, C.L.; Stevenson, M.R.; Scassellati, B. Secret-sharing: Interactions between a child, robot, and adult. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Anchorage, AK, USA, 9–12 October 2011; pp. 2489–2494. [Google Scholar]

- Martelaro, N.; Nneji, V.C.; Ju, W.; Hinds, P. Tell me more designing HRI to encourage more trust, disclosure, and companionship. In Proceedings of the 2016 11th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), Christchurch New Zealand, 7 March 2016; pp. 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, G.; Birnbaum, G.E.; Vanunu, K.; Sass, O.; Reis, H.T. Robot responsiveness to human disclosure affects social impression and appeal. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Bielefeld, Germany, 3–6 March 2014; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal-von der Pütten, A.M.; Krämer, N.C.; Herrmann, J. The effects of humanlike and robot-specific affective nonverbal behavior on perception, emotion, and behavior. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2018, 10, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paine, A.L.; McCarthy Veach, P.; MacFarlane, I.M.; Thomas, B.; Ahrens, M.; LeRoy, B.S. “What Would You Do if You Were Me?” Effects of Counselor Self-Disclosure Versus Non-disclosure in a Hypothetical Genetic Counseling Session. J. Genet. Couns. 2010, 19, 570–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman-Graff, M.A. Interviewer use of positive and negative self-disclosure and interviewer-subject sex pairing. J. Couns. Psychol. 1977, 24, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeForest, C.; Stone, G.L. Effects of sex and intimacy level on self-disclosure. J. Couns. Psychol. 1980, 27, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, P.R.; Betz, N.E. Differential effects of self-disclosing versus self-involving counselor statements. J. Couns. Psychol. 1978, 25, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, S.J.; D’Augelli, A.R.; Brock, G.W. An evaluation of helping skills training: Effects on helpers’ verbal responses. J. Couns. Psychol. 1976, 23, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, I.; Taylor, D.A. Social Penetration: The Development of Interpersonal Relationships; Holt, Rinehart & Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau, J.-P.; Barrett, L.F.; Rovine, M.J. The interpersonal process model of intimacy in marriage: A daily-diary and multilevel modeling approach. J. Fam. Psychol. 2005, 19, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprecher, S.K.; Hendrick, S.S. Self-disclosure in intimate relationships: Associations with individual and relationship characteristics over time. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 23, 857–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breazeal, C. Emotion and sociable humanoid robots. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2003, 59, 119–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Benbasat, I. Para-social presence and communication capabilities of a web site: A theoretical perspective. e-Service 2002, 1, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.H.; Gratch, J. Virtual humans elicit socially anxious interactants’ verbal self-disclosure. Comput. Animat. Virtual Worlds 2010, 21, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Morency, L.-P.; Gratch, J. Virtual Rapport 2. In 0. In Proceedings of the International workshop on Intelligent Virtual Agents, Reykjavik, Iceland, 15–17 September 2011; pp. 68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.-H.; Gratch, J.; Sidner, C.; Artstein, R.; Huang, L.; Morency, L.-P. Towards building a virtual counselor: Modeling nonverbal behavior during intimate self-disclosure. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems-Volume 1, Valencia, Spain, 4–8 June 2012; pp. 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, R.; Papangelis, A.; Cassell, J. Towards a dyadic computational model of rapport management for human-virtual agent interaction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, Boston, MA, USA, 27–29 August 2014; pp. 514–527. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, P.; McGill, A.L. Is that car smiling at me? Schema congruity as a basis for evaluating anthropomorphized products. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, N.; Waytz, A.; Cacioppo, J.T. On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 114, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, C.I.; Moon, Y.; Morkes, J. Computers are social actors: A review of current. Hum. Values Des. Comput. Technol. 1997, 72, 137. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, Y.; Nass, C. How “real” are computer personalities? Psychological responses to personality types in human-computer interaction. Commun. Res. 1996, 23, 651–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, C.; Moon, Y.; Fogg, B.J.; Reeves, B.; Dryer, D.C. Can computer personalities be human personalities? Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 1995, 43, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy Veach, P. Reflections on the meaning of clinician self-reference: Are we speaking the same language? Psychotherapy 2011, 48, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, H.T. Intimacy as an interpersonal process. In Relationships, Well-Being and Behaviour; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 113–143. [Google Scholar]

- Forest, A.L.; Wood, J.V. When partner caring leads to sharing: Partner responsiveness increases expressivity, but only for individuals with low self-esteem. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 47, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, S.; Chaudry, H. Gender-based differences in the patterns of emotional self-disclosure. Pak. J. Psychol. Res. 2008, 23, 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, E.; Emerson, R. Social exchange theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1976, 2, 335–362. [Google Scholar]

- Rotenberg, K.J.; Chase, N. Development of the reciprocity of self-disclosure. J. Genet. Psychol. 1992, 153, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano, C.H.; Dunnam, M. Two’s company: Self-disclosure and reciprocity in triads versus dyads. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1985, 48, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, C.; Moon, Y. Machines and mindlessness: Social responses to computers. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Nass, C. The multiple source effect and synthesized speech: Doubly-disembodied language as a conceptual framework. Hum. Commun. Res. 2004, 30, 182–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biocca, F. The cyborg’s dilemma: Progressive embodiment in virtual environments. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 1997, 3, JCMC324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S.S. The MAIN Model: A Heuristic Approach to Understanding Technology Effects on Credibility; MacArthur Foundation Digital Media and Learning Initiative: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.J. Interacting socially with the Internet of Things (IoT): Effects of source attribution and specialization in human–IoT interaction. J. Comput. -Mediat. Commun. 2016, 21, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Such, J.M.; Espinosa, A.; García-Fornes, A. A survey of privacy in multi-agent systems. Knowl. Eng. Rev. 2014, 29, 314–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Iorga, M.; Voas, J.; Lee, S. Alexa, can I trust you? Computer 2017, 50, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venturebeat. IoT Device Pairing Raises Privacy Concerns for Home AI. Available online: https://venturebeat.com/ai/iot-device-pairing-raises-privacy-concerns-for-home-ai/ (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Lee, H.; Wong, S.F.; Oh, J.; Chang, Y. Information privacy concerns and demographic characteristics: Data from a Korean media panel survey. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, G.; Bolsover, G.; Dubois, E. A new privacy paradox: Young people and privacy on social network sites. In Proceedings of the Prepared for the Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association, San Francisco, CA, USA, 16–19 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kezer, M.; Sevi, B.; Cemalcilar, Z.; Baruh, L. Age differences in privacy attitudes, literacy and privacy management on Facebook. Cyberpsychol. J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2016, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.J. Digital literacy and privacy behavior online. Commun. Res. 2013, 40, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paine, C.; Reips, U.-D.; Stieger, S.; Joinson, A.; Buchanan, T. Internet users’ perceptions of ‘privacy concerns’ and ‘privacy actions’. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2007, 65, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, S. Teenagers’ perceptions of online privacy and coping behaviors: A risk–benefit appraisal approach. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2005, 49, 86–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solove, D.J. A taxonomy of privacy. U. Pa. L. Rev. 2005, 154, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, S.S.; Agarwal, J. Internet users’ information privacy concerns (IUIPC): The construct, the scale, and a causal model. Inf. Syst. Res. 2004, 15, 336–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastlick, M.A.; Lotz, S.L.; Warrington, P. Understanding online B-to-C relationships: An integrated model of privacy concerns, trust, and commitment. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.N.; Dillman Taylor, D. Concerns about confidentiality: The application of ethical decision-making within group play therapy. Int. J. Play Ther. 2014, 23, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprecher, S.; Treger, S.; Wondra, J.D.; Hilaire, N.; Wallpe, K. Taking turns: Reciprocal self-disclosure promotes liking in initial interactions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 49, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Choi, J. Enhancing user experience with conversational agent for movie recommendation: Effects of self-disclosure and reciprocity. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2017, 103, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnova, H.; Spiekermann, S.; Koroleva, K.; Hildebrand, T. Online social networks: Why we disclose. J. Inf. Technol. 2010, 25, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, A.W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.D.; Brown, T.L.; Caven, B.; Haake, S.; Schmidt, K. Does a speech-based interface for an in-vehicle computer distract drivers? In Proceedings of the World Congress on Intelligent Transport System, San Francisco, CA, USA, 6–9 November 2000.

- Jung, S.; Sandor, C.; Wisniewski, P.J.; Hughes, C.E. Realme: The influence of body and hand representations on body ownership and presence. In Proceedings of the 5th Symposium on Spatial User Interaction, New York, NY, USA, 16–17 October 2017; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Caine, K. Local standards for sample size at CHI. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; pp. 981–992. [Google Scholar]

- Cowie, R.; Douglas-Cowie, E.; Tsapatsoulis, N.; Votsis, G.; Kollias, S.; Fellenz, W.; Taylor, J.G. Emotion recognition in human-computer interaction. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2001, 18, 32–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y. Intimate exchanges: Using computers to elicit self-disclosure from consumers. J. Consum. Res. 2000, 26, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeless, L.R.; Grotz, J. Conceptualization and measurement of reported self-disclosure. Hum. Commun. Res. 1976, 2, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeless, L.R. A follow-up study of the relationships among trust, disclosure, and interpersonal solidarity. Hum. Commun. Res. 1978, 4, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey, C.; Lowry, P.B.; Roberts, T.L.; Ellis, T.S. Proposing the online community self-disclosure model: The case of working professionals in France and the UK who use online communities. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2010, 19, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.-C. The determinants of continuous use of social networking sites: An empirical study on Taiwanese journal-type bloggers’ continuous self-disclosure behavior. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2013, 12, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Min, Q.; Zhai, Q.; Smyth, R. Self-disclosure in Chinese micro-blogging: A social exchange theory perspective. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbaugh, E.E.; Ferris, A.L. Predictors of honesty, intent, and valence of Facebook self-disclosure. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.L.-Y.; Leung, L. Unwillingness-to-communicate, perceptions of the Internet and self-disclosure in ICQ. Telemat. Inform. 2006, 23, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.L.; Ellison, N.B.; Heino, R.D. Self-presentation in online personals: The role of anticipated future interaction, self-disclosure, and perceived success in Internet dating. Commun. Res. 2006, 33, 152–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.; Boudreau, M.-C. Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segars, A.H.; Grover, V. Strategic information systems planning success: An investigation of the construct and its measurement. MIS Q. 1998, 22, 139–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakeman, R. Recommended effect size statistics for repeated measures designs. Behav. Res. Methods 2005, 37, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, J.E. Psychotherapist self-disclosure: Ethical and clinical considerations. Psychotherapy 2011, 48, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, Z.D. More than a mirror: The ethics of therapist self-disclosure. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 2002, 39, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturges, J.W. Use of therapist self-disclosure and self-involving statements. Behav. Ther. 2012, 35, 90–93. [Google Scholar]

- Audet, C.T.; Everall, R.D. Therapist self-disclosure and the therapeutic relationship: A phenomenological study from the client perspective. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2010, 38, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Contents | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity of the interaction partner [39,40,41,42] | Powers et al. (2007) [39] | Computer agent/Humanoid robot | agent is more effective |

| Lucas, et al. (2014) [40] | A virtual human interviewer as computer or human | Virtual humans increase willingness to disclose | |

| Pickard, Roster, and Chen (2016) [41] | Preferences for partner identity change with information sensitivity | Participants preferred avatar interviewers for more sensitive topics and preferred human interviewers for less sensitive topics | |

| Kumazaki et al. (2018) [42] | The effect of the android and simplistic humanoid robots on the self- disclosure | Simple robots are more effective on the self-disclosure of ASD adolescents | |

| Character traits of the interaction partner [43,44,45] | Mumm and Mutlu (2011) [43] | Study on how robot likeability affects the psychological distance | The robot’s likeability marginally affected human self-disclosure |

| Bethel, Stevenson, and Scassellati (2011) [44] | On the possibility that robots can collect sensitive information of children | Robots’ prompting efforts should be of a similar level to that of adults | |

| Martelaro, Nenji, Ju, and Hinds. (2016) [45] | Effects of robot vulnerability and expressivity on user trust, companionship and disclosure | While vulnerability increased trust and companionship, expressivity increased the disclosure. | |

| The response of the interaction partner [46,47] | Hoffman et al. (2014) [46] | PPR (perceived partner responsiveness) of a robot | The higher the PPR of a robot, the more self-disclosure people had |

| Rosenthal-von der Pütten et al. (2018) [47] | Classified non-verbal behaviors of an artificial entity into HNB (human-like non-verbal Behavior) and RNB (robot-specific non-verbal behavior) | All types of non-verbal behavior increase the breadth of self-disclosure |

| Within-Subjects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV1 (2-level) | Low Disclosing Robot | High Disclosing Robot | |||

| IV2 (2-level) | Low Involving User | High Involving User | Low Involving User | High Involving User | |

| Between-subjects MoV | Single robot N = 15 | S(0,0) | S(0,1) | S(1,0) | S(1,1) |

| Multi-robot N = 16 | M(0,0) | M(0,1) | M(1,0) | M(1,1) | |

| IVs, MoV Condition | DV (User Self-Disclosure) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disclosing Robot | Involving User | Multi- or Single-Robot | Speech Length | Amount | Depth |

| Low | Low | Multi | 22.28 (12.22) | 3.67 (1.66) | 3.95 (1.74) |

| Single | 16.33 (7.34) | 2.89 (1.58) | 3.14 (1.93) | ||

| High | Low | Multi | 25.07 (9.06) | 4.44 (1.48) | 4.33 (1.71) |

| Single | 20.45 (6.04) | 4.36 (1.46) | 4.56 (1.68) | ||

| Low | High | Multi | 25.07 (13.43) | 5.56 (0.85) | 6.05 (0.78) |

| Single | 25.05 (12.81) | 4.94 (1.45) | 5.33 (1.44) | ||

| High | High | Multi | 34.51 (12.57) | 5.54 (1.05) | 5.64 (1.58) |

| Single | 37.67 (13.77) | 4.81 (1.30) | 5.75 (1.15) | ||

| DV | IVs, MoV | F Statistic | Significance Level | Generalized Eta-Squared | Hypotheses Supported (for Speech Length) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speech length | DR | F(1,23) = 28.894 | p < 0.001 *** | ηG2 = 0.256 | H1: Supported |

| IU | F(1,23) = 35.756 | p < 0.001 *** | ηG2 = 0.374 | H2: Supported | |

| DR × IU | F(1,23) = 8.735 | p = 0.007 ** | ηG2 = 0.086 | H3: Supported | |

| DR × Multi-robot | F(1,23) = 0.699 | P = 0.412 | ηG2 = 0.008 | H4: Not supported | |

| IU × Multi-robot | F(1,23) = 4.604 | p = 0.043 * | ηG2 = 0.071 | H5: Supported |

| DV | IVs, MoV | F Statistic | Significance Level | Generalized Eta-Squared | Hypotheses Supported (for Depth) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depth | DR | F(1,23) = 4.649 | p = 0.042 * | ηG2 = 0.023 | H1: Supported |

| IU | F(1,23) = 31.395 | p < 0.001 *** | ηG2 = 0.249 | H2: Supported | |

| DR × IU | F(1,23) = 3.179 | p = 0.088 | ηG2 = 0.023 | H3: Marginally Supported | |

| DR × Multi-robot | F(1,23) = 4.916 | p = 0.037 * | ηG2 = 0.024 | H4: Supported | |

| IU × Multi-robot | F(1,23) = 0.000 | p = 0.986 | ηG2 = 0.000 | H5: Not Supported |

| DV | IVs, MoV | F Statistic | Significance Level | Generalized Eta-Squared | Hypotheses Supported (for Amount) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | DR | F(1,23) = 4.359 | p = 0.048 * | ηG2 = 0.037 | H1: Supported |

| IU | F(1,23) = 24.254 | p < 0.001 *** | ηG2 = 0.213 | H2: Supported | |

| DR × IU | F(1,23) = 7.982 | p = 0.010 * | ηG2 = 0.049 | H3: Partially supported | |

| DR × Multi-robot | F(1,23) = 0.351 | p = 0.559 | ηG2 = 0.003 | H4: Not supported | |

| IU × Multi-robot | F(1,23) = 0.200 | p = 0.659 | ηG2 = 0.002 | H5: Not Supported |

| Hypotheses | IVs, MoV | DV Sub-Dimension | p-Value | Remark | Hypotheses Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Disclosing robot | Speech length | p < 0.001 *** | O | Supported |

| Depth | p = 0.042 * | O | |||

| Amount | p = 0.048 * | O | |||

| H2 | Involving user | Speech length | p < 0.001 *** | O | Supported |

| Depth | p < 0.001 *** | O | |||

| Amount | p < 0.001 *** | O | |||

| H3 | Disclosing robot × Involving user | Speech length | p = 0.007 ** | O | Partially Supported |

| Depth | p = 0.088 | Different direction | |||

| Amount | p = 0.010 * | Different direction | |||

| H4 | Disclosing robot × Multi-robot | Speech length | p = 0.412 | Partially Supported | |

| Depth | p = 0.037 * | O | |||

| Amount | p = 0.559 | ||||

| H5 | Involving user × Multi-robot | Speech length | p = 0.043 * | O | Partially Supported |

| Depth | p = 0.986 | ||||

| Amount | p = 0.659 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, B.; Park, D.; Yoon, J.; Kim, J. Better Data from AI Users: A Field Experiment on the Impacts of Robot Self-Disclosure on the Utterance of Child Users in Home Environment. Sensors 2023, 23, 3026. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23063026

Lee B, Park D, Yoon J, Kim J. Better Data from AI Users: A Field Experiment on the Impacts of Robot Self-Disclosure on the Utterance of Child Users in Home Environment. Sensors. 2023; 23(6):3026. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23063026

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Byounggwan, Doeun Park, Junhee Yoon, and Jinwoo Kim. 2023. "Better Data from AI Users: A Field Experiment on the Impacts of Robot Self-Disclosure on the Utterance of Child Users in Home Environment" Sensors 23, no. 6: 3026. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23063026

APA StyleLee, B., Park, D., Yoon, J., & Kim, J. (2023). Better Data from AI Users: A Field Experiment on the Impacts of Robot Self-Disclosure on the Utterance of Child Users in Home Environment. Sensors, 23(6), 3026. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23063026