Point-of-Care Fluorescence Biosensing System for Rapid Multi-Allergen Screening †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

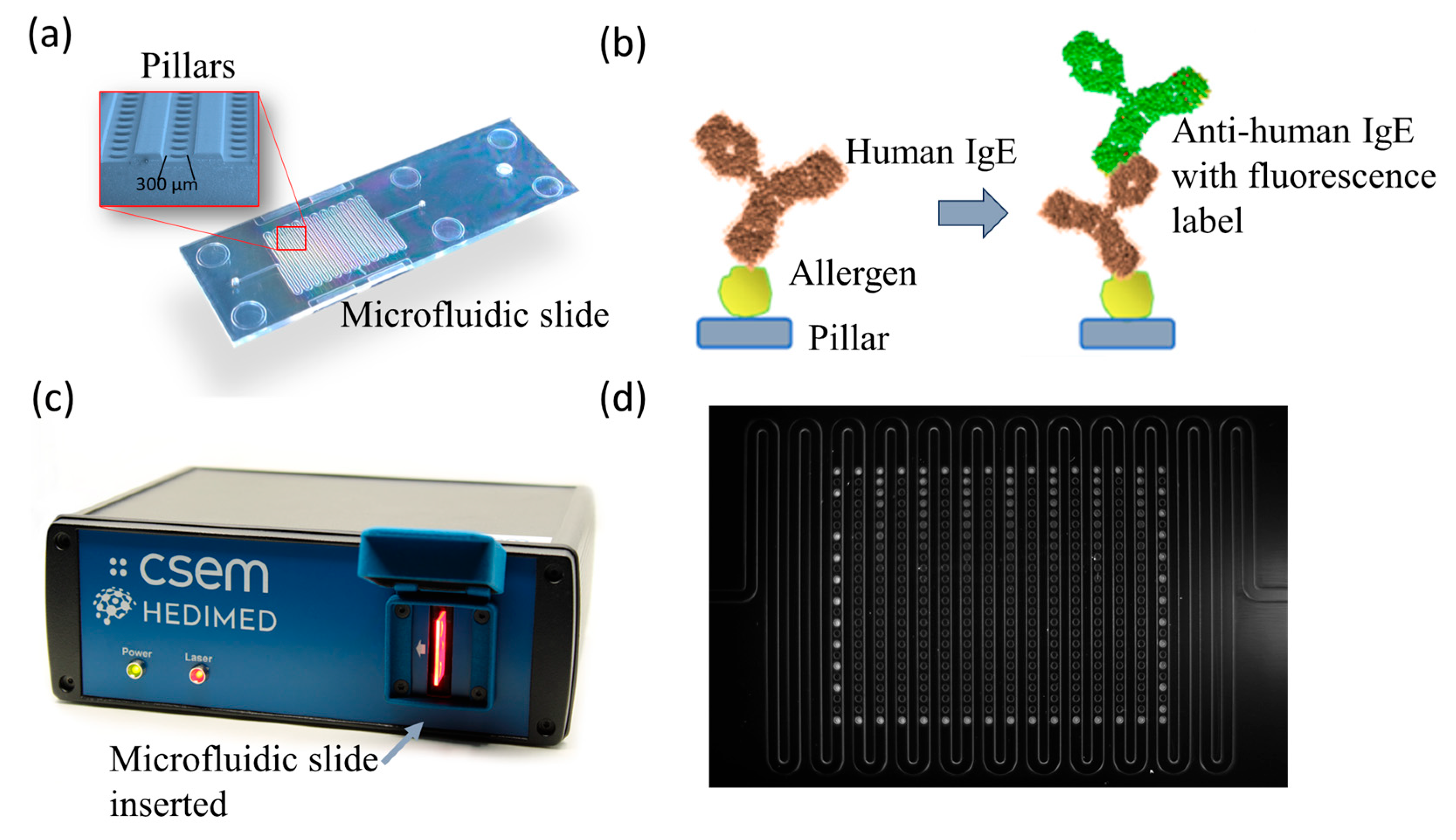

3.1. Development of the Portable Fluorescence System

3.1.1. Microarray Assay

3.1.2. Portable Reader

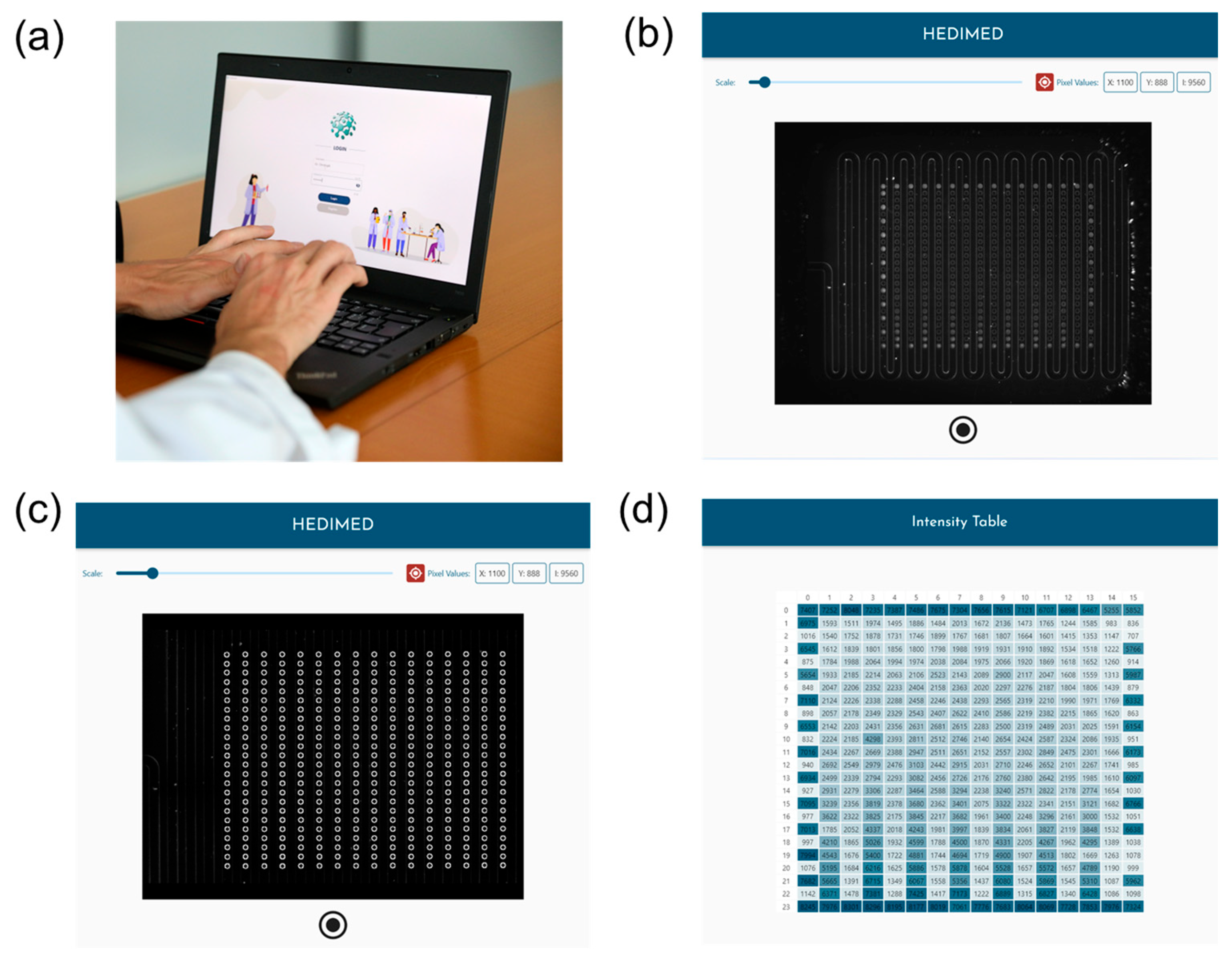

3.1.3. The Custom Software

3.2. Specific IgE Detection in Control Serum Samples

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, F.; Jia, H.; Zou, Y.; Yao, Y.; Deng, Z. Exosomes: An Important Messenger in the Asthma Inflammatory Microenvironment. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 0300060520903220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawankar, R. Allergic Diseases and Asthma: A Global Public Health Concern and a Call to Action. World Allergy Organ. J. 2014, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laiho, J.E.; Laitinen, O.H.; Malkamäki, J.; Puustinen, L.; Sinkkonen, A.; Pärkkä, J.; Hyöty, H.; Anna, E.; Heikki, H.; Kalle, K.; et al. Exposomic Determinants of Immune-Mediated Diseases: Special Focus on Type 1 Diabetes, Celiac Disease, Asthma, and Allergies: The HEDIMED Project Approach. Environ. Epidemiol. 2022, 6, e212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Allergy Organization. White Book on Allergy, 2011th ed.; Pawankar, R., Canonica, G.W., Holgate, S.T., Lockey, R.F., Eds.; World Allergy Organization (WAO): London, UK, 2011; pp. 1–225. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak-Węgrzyn, A.; Assa’ad, A.H.; Bahna, S.L.; Bock, S.A.; Sicherer, S.H.; Teuber, S.S.; Adverse Reactions to Food Committee of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. Work Group Report: Oral Food Challenge Testing. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 123, S365–S378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousquet, J.; Heinzerling, L.; Bachert, C.; Papadopoulos, N.G.; Bousquet, P.J. Practical Guide to Skin Prick Tests in Allergy to Aeroallergens. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 67, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, A.; Velázquez-soto, H.; Ayala-balboa, J.; Jiménez-martínez, M.C.; Salazar, A.; Velázquez-soto, H.; Ayala-balboa, J. Allergen-Based Diagnostic: Novel and Old Methodologies with New Approaches, 2017th ed.; Athari, S.S., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Palareti, G.; Legnani, C.; Cosmi, B.; Antonucci, E.; Erba, N.; Poli, D.; Testa, S.; Tosetto, A. Comparison between Different D-Dimer Cutoff Values to Assess the Individual Risk of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism: Analysis of Results Obtained in the DULCIS Study. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2016, 38, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesler, V.; Murmann, B.; Soh, H.T. Going beyond the Debye Length: Overcoming Charge Screening Limitations in Next-Generation Bioelectronic Sensors. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 16194–16201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbáth, M.; Papp, K.; Balogh, A. Applications of Antibodies in Microfluidics-Based Analytical Systems: Challenges and Strategies for Success Exploiting Fluorescence for Multiplex Immunoassays on Protein Microarrays. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2018, 28, 063001. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, J.; Wu, Y.; Qin, F.; Su, M.; Cheng, N.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Lian, Z.; Yang, X.; Cheng, L.; et al. All-Printed Point-of-Care Immunosensing Biochip for One Drop Blood Diagnostics. Lab Chip 2022, 22, 3008–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rengganis, I.; Rambe, D.S.; Rumende, C.M.; Abdullah, M. Total Serum IgE Levels among Adults Patients with Intermittent and Persistent Allergic Asthmas. Med. J. Indones 2018, 27, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R.G. Allergy Clinical and Research Laboratory—Immunological Methods in the Diagnostic Allergy Clinical and Research Laboratory, 6th ed.; Rose, N., Hamilton, R., Detrick, B., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 883–890. [Google Scholar]

- Vallier, P.; DeChamp, C.; Valenta, R.; Vial, O.; Deviller, P. Purification and Characterization of an Allergen from Celery Immunochemically Related to an Allergen Present in Several Other Plant Species. Identification as a Profilin. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1992, 22, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tscheppe, A.; Breiteneder, H. Recombinant Allergens in Structural Biology, Diagnosis, and Immunotherapy. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2017, 172, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupinek, C.; Wollmann, E.; Baar, A.; Banerjee, S.; Breiteneder, H.; Broecker, B.M.; Bublin, M.; Curin, M.; Flicker, S.; Garmatiuk, T.; et al. Advances in Allergen-Microarray Technology for Diagnosis and Monitoring of Allergy: The MeDALL Allergen-Chip. Methods 2014, 66, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Demuru, S.; Chai-Gao, H.; Shynkarenko, Y.; Hermann, N.; Boia, P.-D.; Cristofolini, P.; Petkus, B.; Generelli, S.; Paoletti, S.; Cattaneo, S.; et al. Point-of-Care Fluorescence Biosensing System for Rapid Multi-Allergen Screening. Sensors 2024, 24, 3280. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113280

Demuru S, Chai-Gao H, Shynkarenko Y, Hermann N, Boia P-D, Cristofolini P, Petkus B, Generelli S, Paoletti S, Cattaneo S, et al. Point-of-Care Fluorescence Biosensing System for Rapid Multi-Allergen Screening. Sensors. 2024; 24(11):3280. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113280

Chicago/Turabian StyleDemuru, Silvia, Hui Chai-Gao, Yevhen Shynkarenko, Nicola Hermann, Patricia-Daiana Boia, Peter Cristofolini, Bradley Petkus, Silvia Generelli, Samantha Paoletti, Stefano Cattaneo, and et al. 2024. "Point-of-Care Fluorescence Biosensing System for Rapid Multi-Allergen Screening" Sensors 24, no. 11: 3280. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113280

APA StyleDemuru, S., Chai-Gao, H., Shynkarenko, Y., Hermann, N., Boia, P.-D., Cristofolini, P., Petkus, B., Generelli, S., Paoletti, S., Cattaneo, S., & Burr, L. (2024). Point-of-Care Fluorescence Biosensing System for Rapid Multi-Allergen Screening. Sensors, 24(11), 3280. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113280