Using 5TE Sensors for Monitoring Moisture Conditions in Green Parks

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- θ = volumetric water content

- Ka = dielectric constant.

2. Related Studies

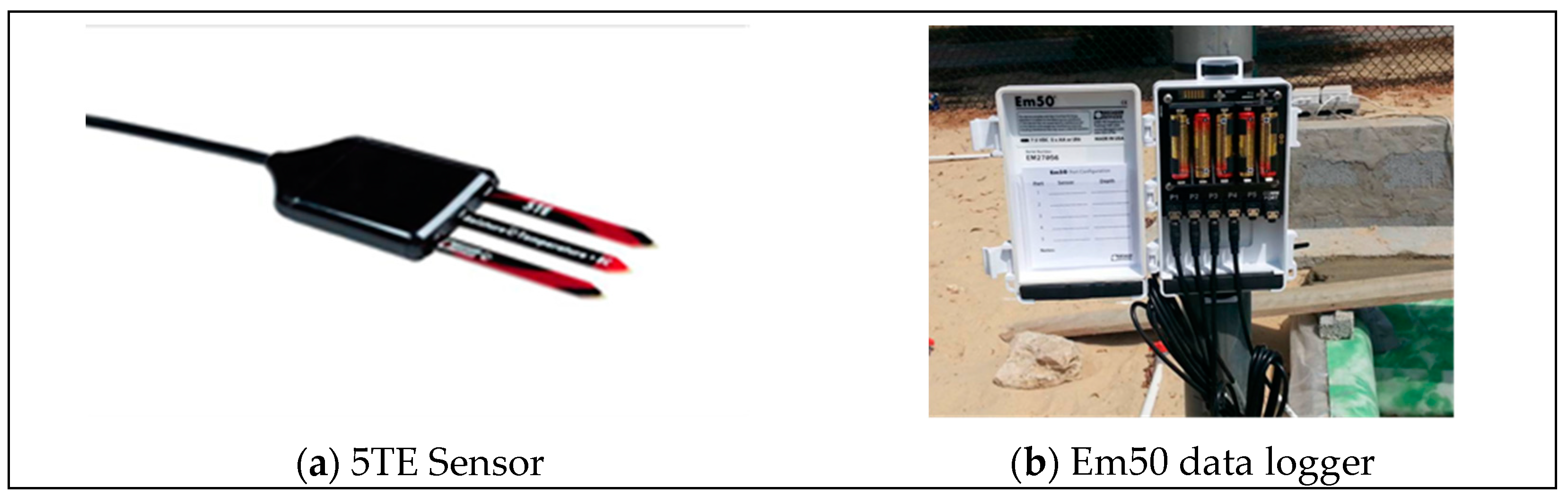

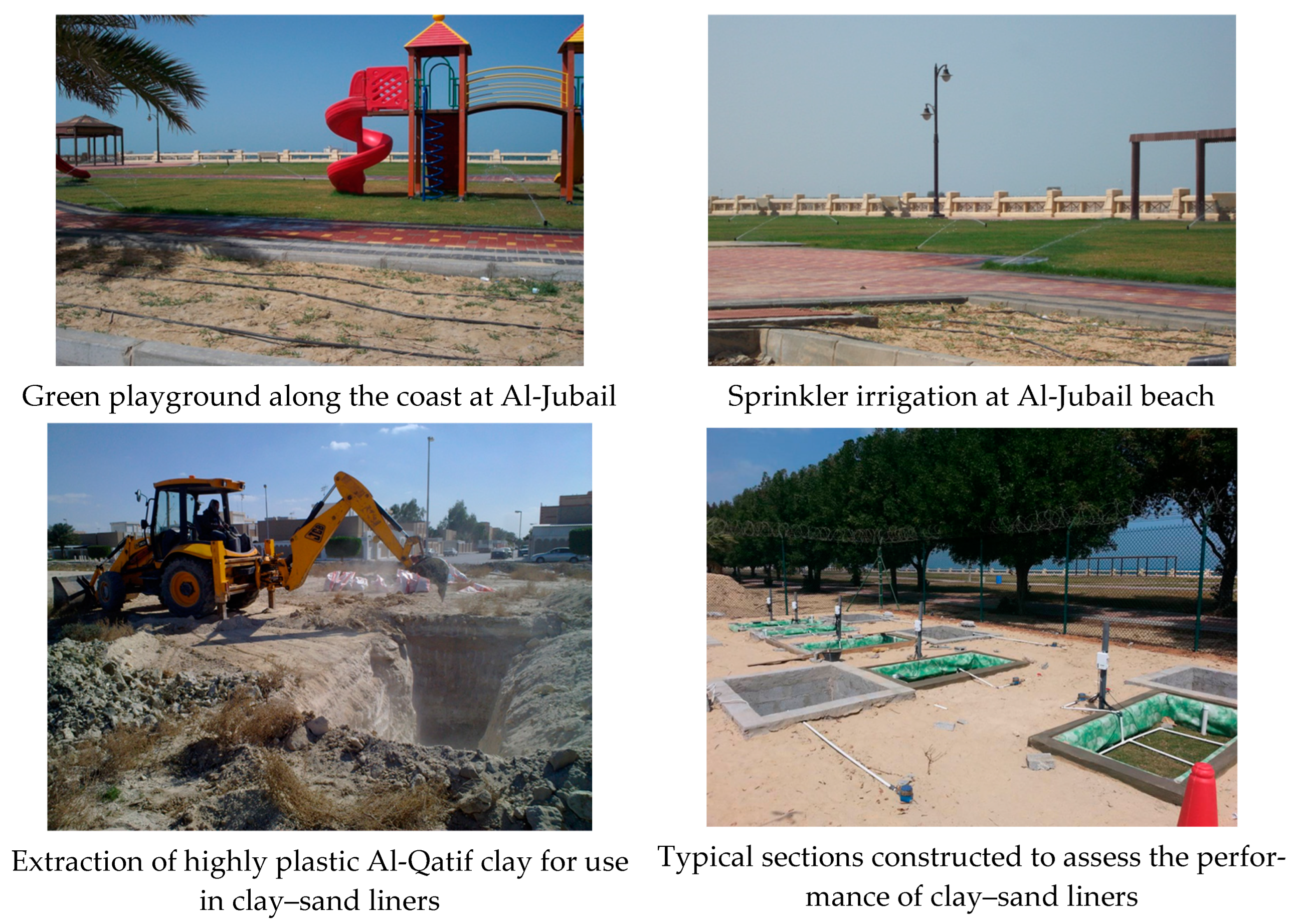

3. Materials and Testing Procedures

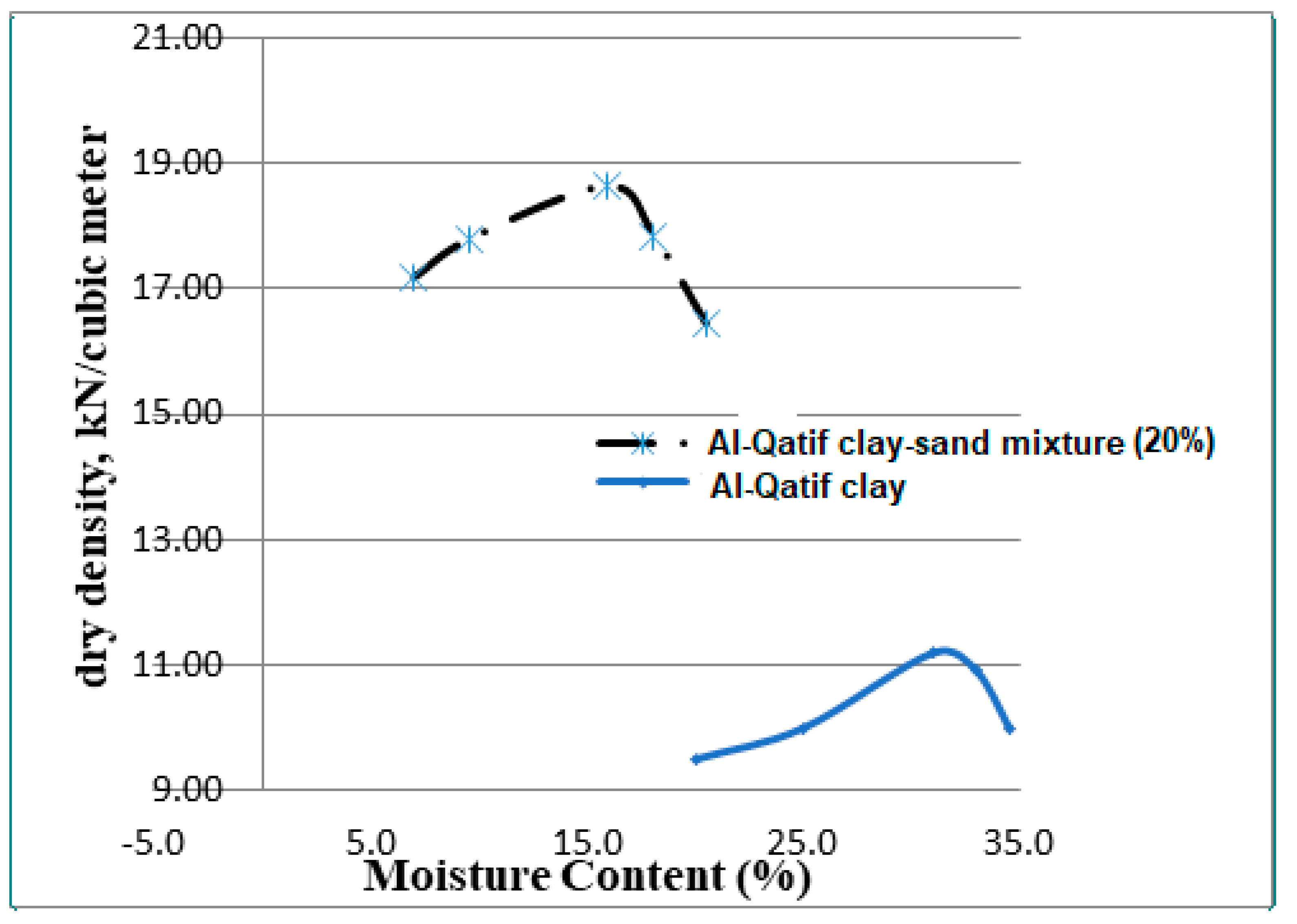

3.1. Materials

3.1.1. Sand

3.1.2. Natural Clay

3.1.3. Bentonite Clay

3.2. Field Sections: Installation and Procedure

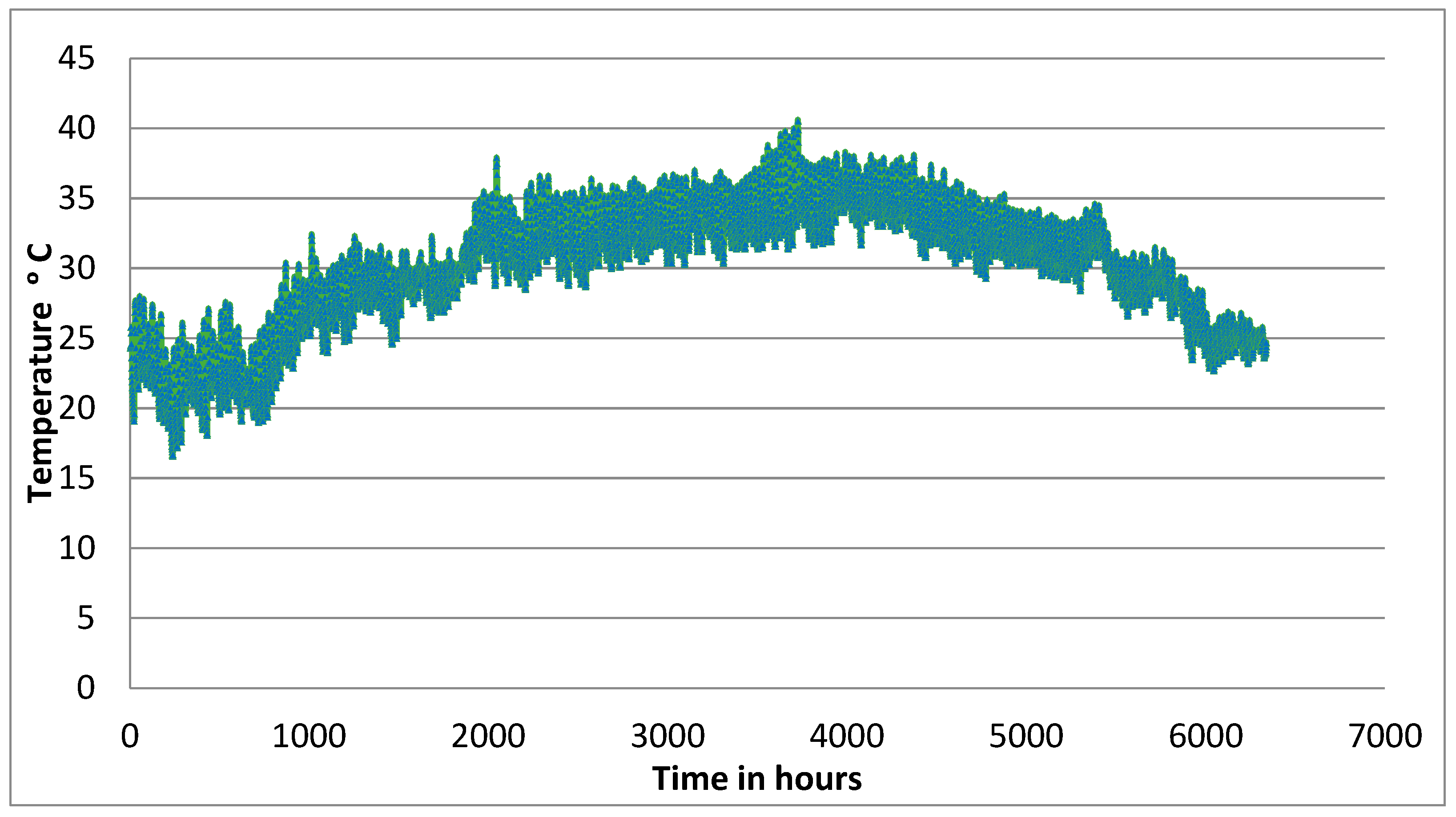

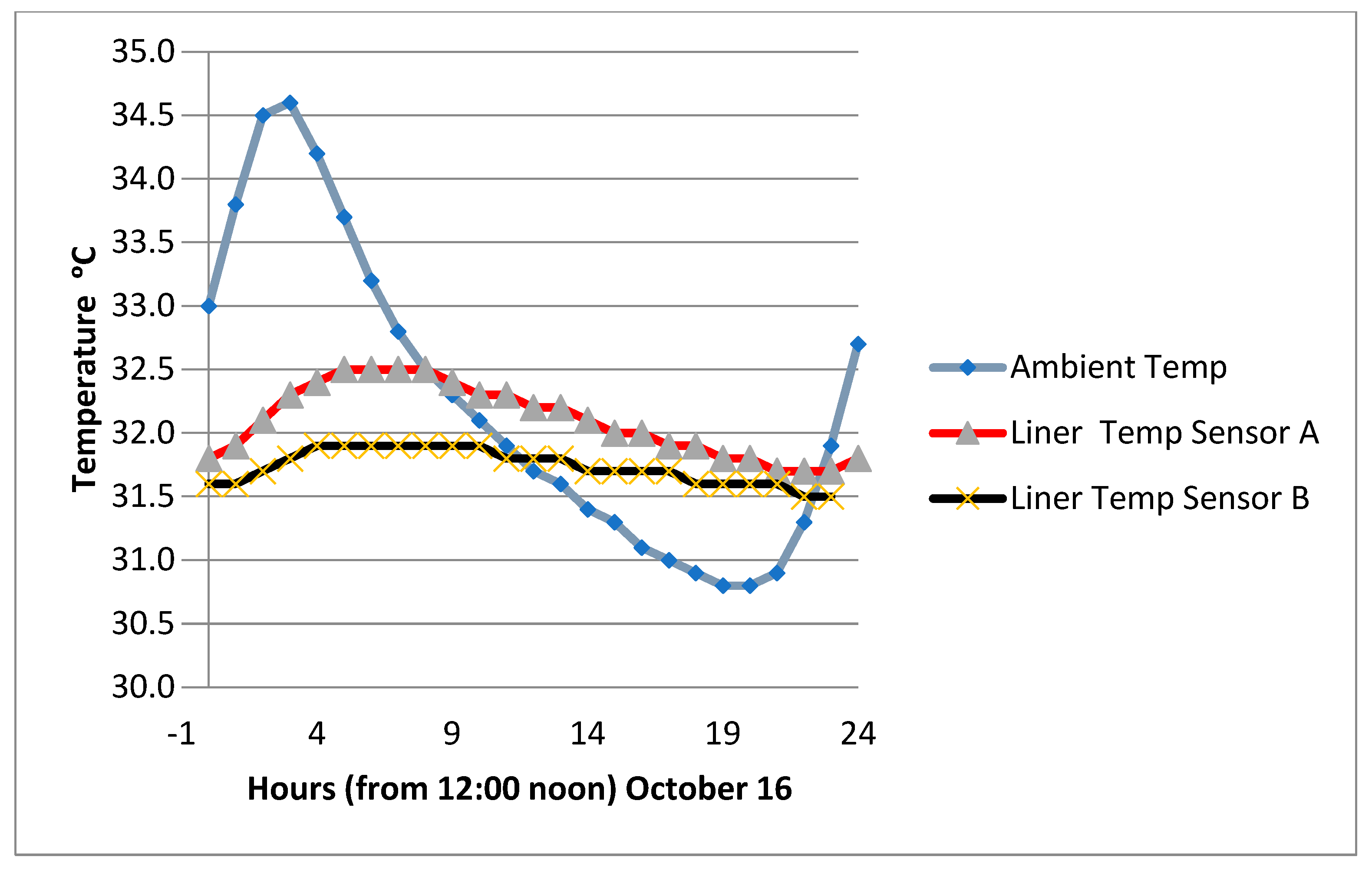

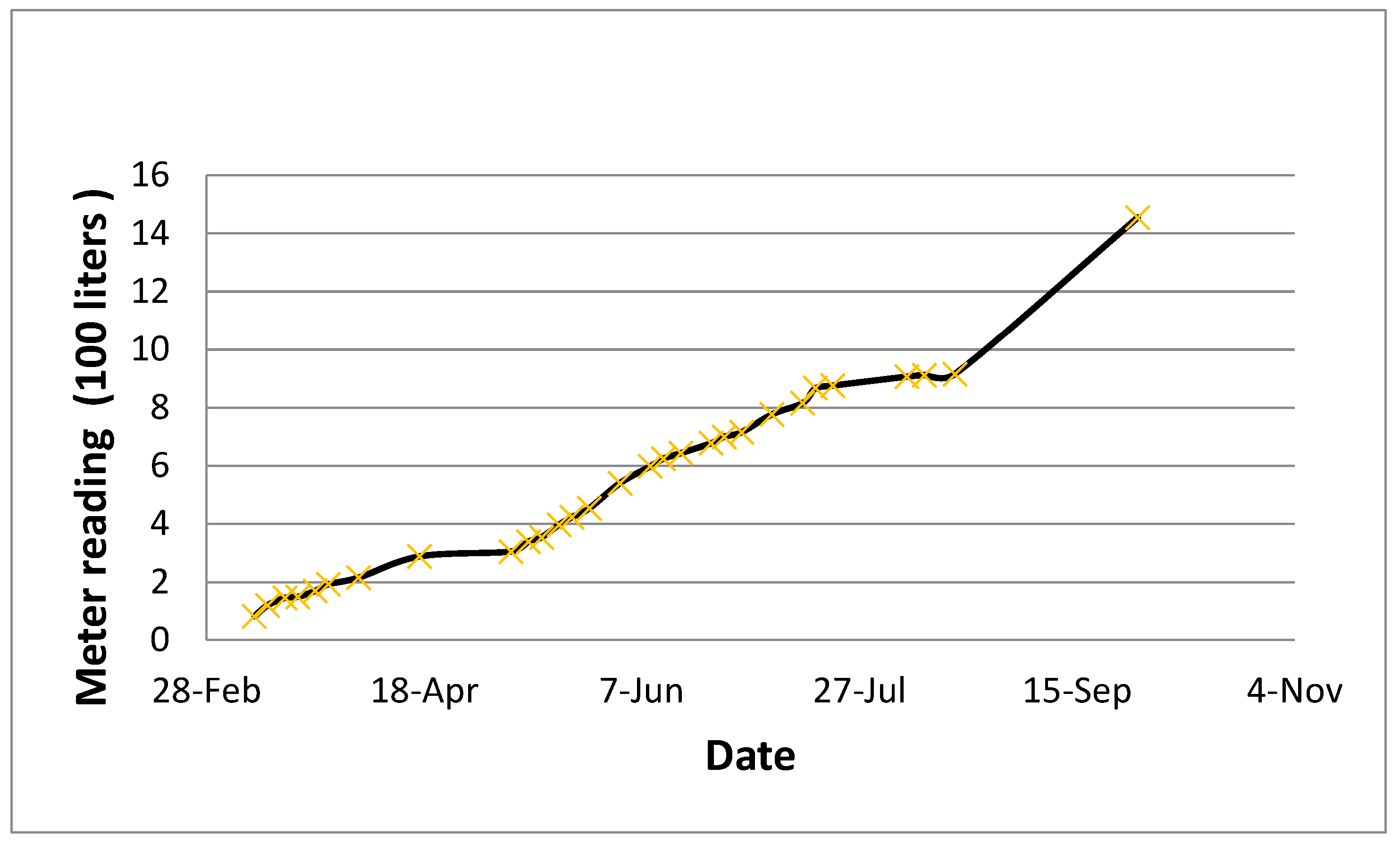

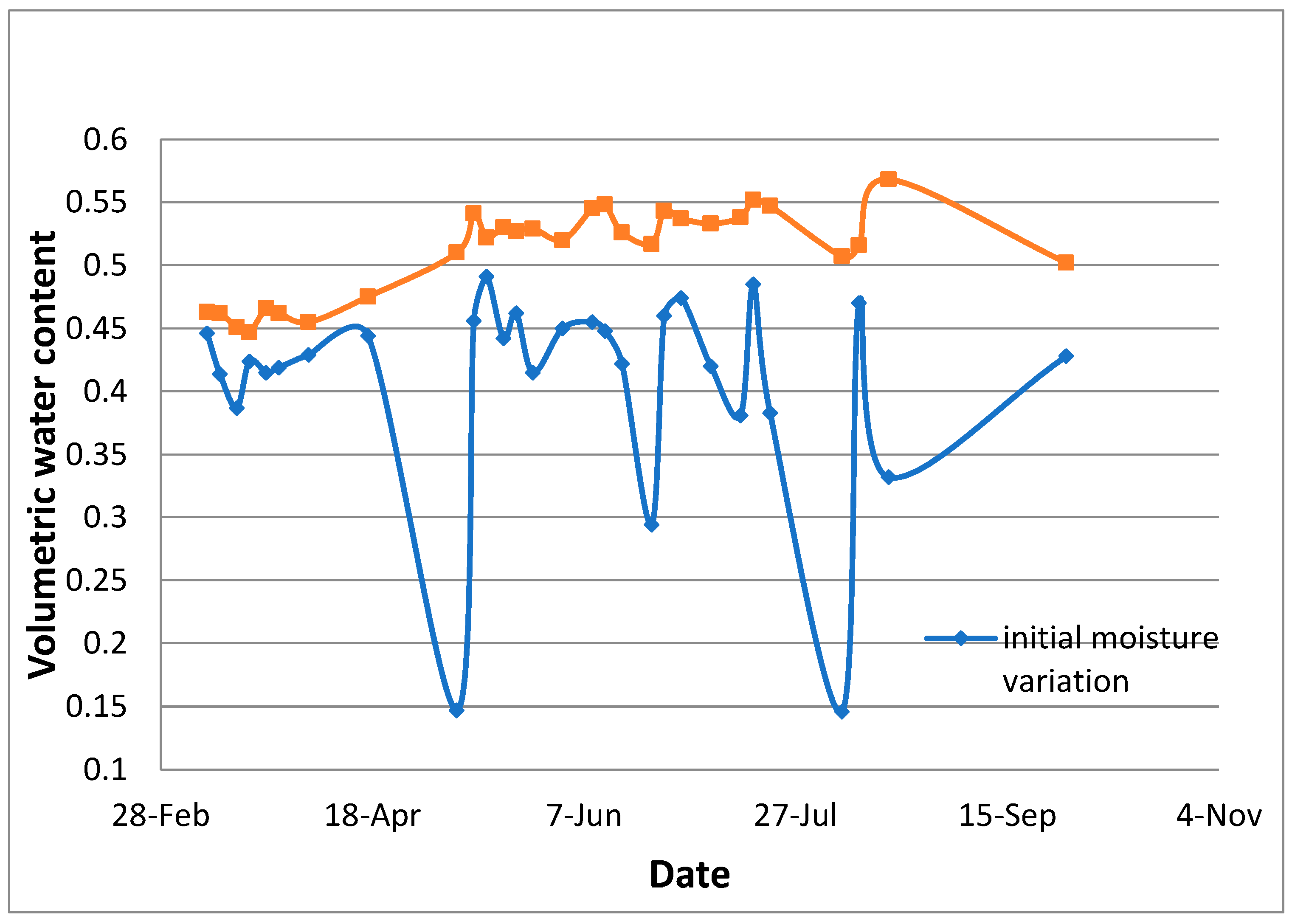

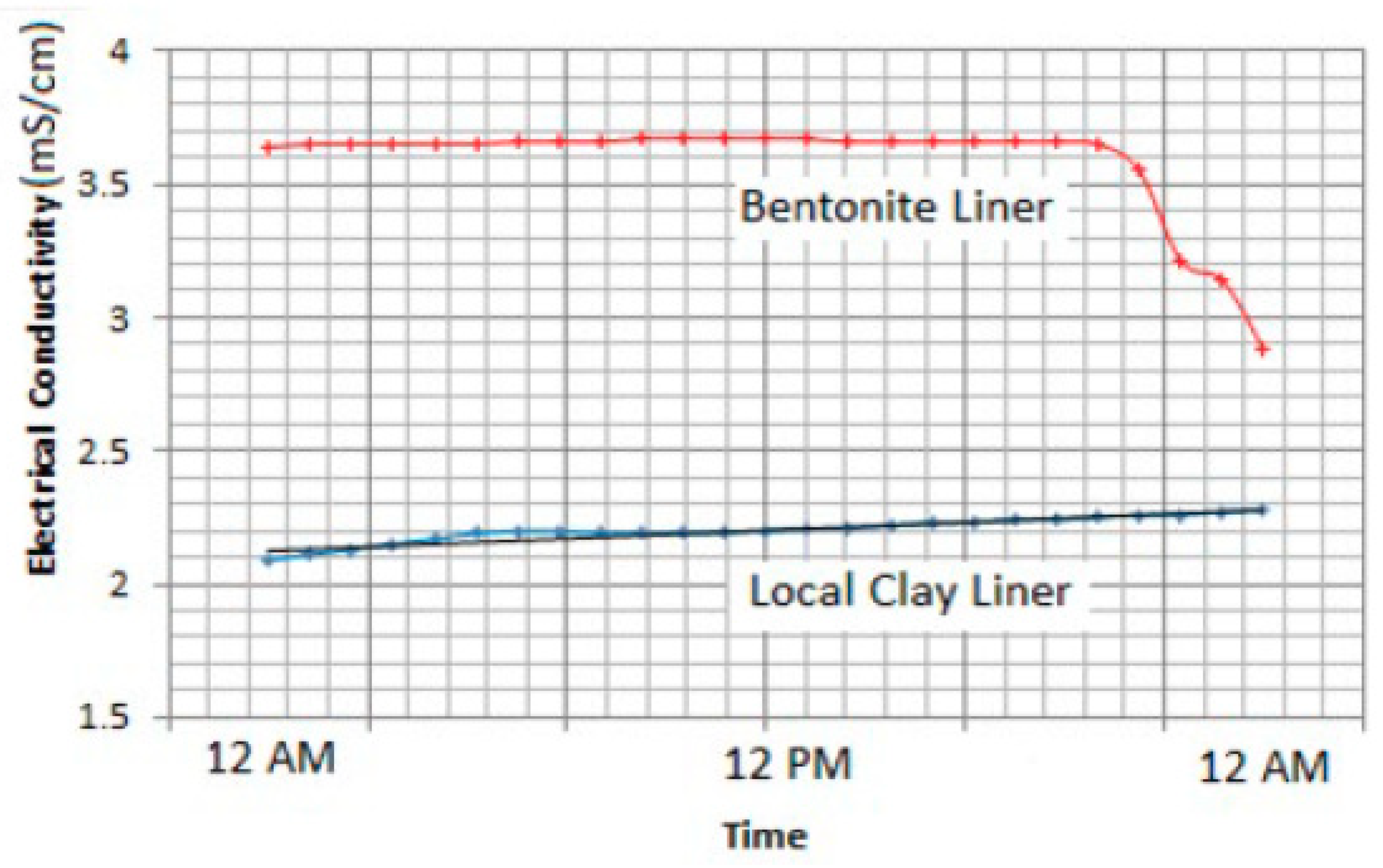

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, H.; Aogu, K.; Li, M.; Xu, J.; Sheng, W.; Jones, S.B.; González-Teruel, J.D.; Robinson, D.A.; Horton, R.; Bristow, K.; et al. Chapter Three—A review of time domain reflectometry (TDR) applications in porous media. Adv. Agron. 2021, 168, 83–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, F.N.; Van Genuchten, M.T. The time-domain reflectometry method for measuring soil water content and salinity. Geoderma 1986, 38, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullo, S.L.; Sinha, G.R. Advances in Smart Environment Monitoring Systems Using IoT and Sensors. Sensors 2020, 20, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Evett, S.R.; Ruthardt, B.B.; Kottkamp, S.T.; Howell, T.A.; Schneider, A.D.; Tolk, J.A. Accuracy and precision of soil water measurements by neutron, capacitance, and TDR methods. In Proceedings of the 17th Water Conservation Soil Society Symposium, Bangkok, Thailand, 14–21 August 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Topp, G.C.; Davis, J.L.; Annan, A.P. Electromagnetic determination of soil water content: Measurements in coaxial transmission lines. Water Resour. Res. 1980, 16, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, I.; Farrugia, L.; Bonello, J.; Sammut, C.; Persico, R. Measuring the Dielectric Properties of Soil: A Review and Some Innovative Proposals. In Instrumentation and Measurement Technologies for Water Cycle Management; Di Mauro, A., Scozzari, A., Soldovieri, F., Eds.; Springer Water; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, G.; Davis, J.; Annan, A. Electromagnetic Determination of Soil WaterContent Using TDR: I. Applications to Wetting Fronts and Steep Gradients 1. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1982, 46, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lei, G.; Kaneza, N.; Yu, X. Evaluation of TDR-Measured Water Content for Dry-Out Curves of Sand Using aModified Tempe Cell Test. Geo-Congress 2023, GSP 343, 634. [Google Scholar]

- Topp, G.C.; Ferré, P.A. Determination of water content. Methods Soil Anal. 2002, 4, 417–545. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, F.; Fares, A.; Fares, S. Field Calibrations of Soil Moisture Sensors in a Forested Watershed. Sensors 2011, 11, 6354–6369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adla, S.; Bruckmaier, F.; Arias-Rodriguez, L.F.; Tripathi, S.; Pande, S.; Disse, M. Impact of calibrating a low-cost capacitance-based soil moisture sensor on AquaCrop model performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- METER Group. ECH2O EC-5 Manual; METER Group: Pullman, WA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- METER Group. ECH2O 5TE Manual; METER Group: Pullman, WA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shmulik, P. Friedman 2004. Soil properties influencing apparent electrical conductivity: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2005, 46, 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mane, S.; Das, N.; Singh, G.; Cosh, M.; Dong, Y. Advancements in dielectric soil moisture sensor Calibration: A comprehensive review of methods and techniques. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 218, 108686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bañón, S.; Ochoa, J.; Bañón, D.; Ortuño, M.F.; Sánchez-Blanco, M.J. Assessment of the Combined Effect of Temperature and Salinity on the Outputs of Soil Dielectric Sensors in Coconut Fiber. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogena, H.R.; Huisman, J.A.; Oberdörster, C.; Vereecken, H. Evaluation of a low-cost soil water content sensor for wireless network applications. J. Hydrol. 2007, 344, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.K.; Kumar, S. Soil Temperature and Plant Growth. In Soil Physical Environment and Plant Growth; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, T.; Incripera, F.; Dewitt, D.; Lavine, A. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mahbashi, A.M.; Al-Shamrani, M.A.; Dafalla, M. Influence of temperature on the retention capacity of clay liners during wetting and drying. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, D.A.; Silva, P.C.; da Costa, A.R.; Delmond, J.G.; Ferreira, A.F.A.; de Souza, J.A.; de Oliveira-Júnior, J.F.; da Silva, J.L.B.; da Rosa Ferraz Jardim, A.M.; Giongo, P.R.; et al. Development and Automation of a Photovoltaic-Powered Soil Moisture Sensor for Water Management. Hydrology 2023, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowla, M.N.; Mowla, N.; Shah, A.S.; Rabie, K.; Shongwe, T. Internet of Things and Wireless Sensor Networks for Smart Agriculture Applications—A Survey. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 145813–145852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balatsouras, C.-P.; Karras, A.; Karras, C.; Karydis, I.; Sioutas, S. WiCHORD+: A Scalable, Sustainable, and P2P Chord-Based Ecosystem for Smart Agriculture Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 9486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payero, J.O. An Effective and Affordable Internet of Things (IoT) Scale System to Measure Crop Water Use. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 823–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariou, C.; Moiroux-Arvis, L.; Pinet, F.; Chanet, J.-P. Internet of underground things in agriculture 4.0: Challenges, applications and per spectives. Sensors 2023, 23, 4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertocco, M.; Parrino, S.; Peruzzi, G.; Pozzebon, A. Estimating volumetric water content in soil for IoUT contexts by exploiting RSSI-based augmented sensors via machine learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hou, J.; Huang, C. Basin Scale Soil Moisture Estimation with Grid SWAT and LESTKF Based on WSN. Sensors 2023, 24, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM D2487-17; Standard Practice for Classification of Soils for Engineering Purposes (Unified Soil Classification System). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. Available online: www.astm.org (accessed on 13 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- Mutaz, E.; Shamrani, M.A.; Puppala, A.J.; Dafalla, M.A. Evaluation of chemical stabilization of a highly expansive clayey soil. J. Transp. Res. Board 2011, 2204, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkady, T.Y.; Dafalla, M.A.; Al-Mahbashi, A.M.; Al-Shamrani, M.A. Evaluation of soil water characteristic curves of sand-clay mixtures. Int. J. Geomate 2013, 4, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D698-12(2021); Standard Test Methods for Laboratory Compaction Characteristics of Soil Using Standard Effort (12,400 ft-lbf/ft³ (600 kN-m/m³)). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. Available online: www.astm.org (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Dafalla, M.A.; Elkady, T.Y.; Al-Shamrani, M.A.; Shaker, A.A. An approach to rank local clays for use in sand clay liners. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Geotechnical Engineering, Hammamet, Tunisia, 21–23 February 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dafallaa, M.; Almajedb, A.; Al-Shamranic, M. Blocking saline fluids using bentonite clay liners: An approach to reduce corrosion. Desalination Water Treat. 2020, 184, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louki, I.I.; Al-Omran, A.M. Calibration of Soil Moisture Sensors (ECH2O-5TE) in Hot and Saline Soils with New Empirical Equation. Agronomy 2023, 13, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Range |

|---|---|

| Material passing sieve number 200 (%) | >90 |

| Liquid limit (%) | 137–140 |

| Plastic limit (%) | 45–60 |

| Plasticity index (%) | 96–99 |

| Maximum dry density (kN/m3) | 11.5–12.0 |

| Optimum moisture content (%) | 32–40 |

| Swell percent, ASTM D4546 [10], (%) | 16–18 |

| Swelling pressure (ASTM D4546) at a density of 12.0 kN/m3 (kN/m3) | 500–800 |

| Property | Al-Qatif Clay | Bentonite Clay |

|---|---|---|

| FeO3, % | <0.1 | 2.9 |

| K2O, % | 2.2 | 0.1 |

| Na2O, % | <0.1 | 1.9 |

| Al2O3, % | 6.3 | 17 |

| MgO, % | <0.1 | 4.6 |

| SiO2, % | 17.3 | 55.2 |

| TiO2, % | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| CaO, % | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Parameter | Details | |

|---|---|---|

| Volumetric Water Content | Range | Apparent dielectric permittivity (εa): 1 (air) to 80 (water) |

| Resolution | εa: 0.1 εa (unit-less) from 1–20, <0.75 εa (unit-less) from 20–80 VWC: 0.0008 m3/m3 (0.08% VWC) from 0 to 50% VWC | |

| Accuracy | (εa): ±1 εa (unit-less) from 1–40 (soil range), ±15% from 40–80 (VWC):

| |

| Electrical Conductivity | Range | 0–23 dS/m (bulk) |

| Resolution | 0.01 dS/m from 0–7 dS/m, 0.05 dS/m from 7–23 dS/m | |

| Accuracy | ±10% from 0–7 dS/m, user calibration required above 7 dS/m | |

| Temperature | Range | −40 to 50 °C |

| Resolution | 0.01 °C | |

| Accuracy | ±1 °C | |

| Date | Initial Inlet Meter Reading | Final Inlet Meter Reading | Quantities Supplied (Liter) | Period of Watering (Minutes) | Impact on vmc | Time to Maximum vmc (Hours) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starting vmc | Maximum vmc | Difference in vmc | ||||||

| 10-March | 0.8229 | 0.9991 | 176.2 | 20 | 0.446 | 0.463 | 0.017 | 8 |

| 13-March | 1.1993 | 1.2662 | 66.9 | 25 | 0.414 | 0.462 | 0.048 | 6 |

| 17-March | 1.4594 | 1.4726 | 13.2 | 20 | 0.387 | 0.451 | 0.064 | 4 |

| 20-March | 1.4948 | 1.6718 | 177 | 20 | 0.424 | 0.447 | 0.023 | 3 |

| 24-March | 1.7007 | 1.9246 | 223.9 | 37 | 0.415 | 0.466 | 0.051 | 3 |

| 27-March | 1.9256 | 2.131 | 205.4 | 42 | 0.419 | 0.462 | 0.043 | 4 |

| 3-April | 2.1572 | 2.2998 | 142.6 | 16 | 0.429 | 0.455 | 0.026 | 4 |

| 17-April | 2.886 | 3.0482 | 162.2 | 46 | 0.444 | 0.475 | 0.031 | 5 |

| 8-May | 3.0539 | 3.3983 | 344.4 | 37 | 0.147 | 0.51 | 0.363 | 6 |

| 12-May | 3.3984 | 3.5432 | 144.8 | 43 | 0.456 | 0.541 | 0.085 | 5 |

| 15-May | 3.5437 | 3.8541 | 310.4 | 55 | 0.491 | 0.522 | 0.031 | 6 |

| 19-May | 3.9736 | 4.2353 | 261.7 | 78 | 0.442 | 0.53 | 0.088 | 3 |

| 22-May | 4.2353 | 4.5438 | 308.5 | 53 | 0.462 | 0.527 | 0.065 | 3 |

| 26-May | 4.5439 | 4.8146 | 270.7 | 42 | 0.415 | 0.529 | 0.114 | 6 |

| 2-June | 5.4019 | 5.547 | 145.1 | 33 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.07 | 2 |

| 9-June | 5.9812 | 6.244 | 262.8 | 33 | 0.455 | 0.545 | 0.09 | 4 |

| 12-June | 6.2441 | 6.3527 | 108.6 | 14 | 0.448 | 0.548 | 0.1 | 4 |

| 16-June | 6.4351 | 6.7668 | 331.7 | 39 | 0.422 | 0.526 | 0.104 | 4 |

| 23-June | 6.7769 | 6.9994 | 222.5 | 32 | 0.294 | 0.517 | 0.223 | 5 |

| 26-June | 6.9994 | 7.0173 | 17.9 | 35 | 0.46 | 0.543 | 0.083 | 3 |

| 30-June | 7.1568 | 7.4156 | 258.8 | 33 | 0.474 | 0.537 | 0.063 | 3 |

| 7-July | 7.7716 | 8.0495 | 277.9 | 23 | 0.42 | 0.533 | 0.113 | 4 |

| 14-July | 8.1574 | 8.4565 | 299.1 | 41 | 0.381 | 0.538 | 0.157 | 5 |

| 17-July | 8.6737 | 8.8589 | 185.2 | 32 | 0.485 | 0.552 | 0.067 | 5 |

| 21-July | 8.7588 | 9.0656 | 306.8 | 41 | 0.383 | 0.547 | 0.164 | 9 |

| 7-August | 9.0656 | 9.1221 | 56.5 | 32 | 0.146 | 0.507 | 0.361 | 3 |

| 11-August | 9.1221 | 9.1579 | 35.8 | 30 | 0.47 | 0.516 | 0.046 | 3 |

| 18-August | 9.1579 | 9.5235 | 365.6 | 59 | 0.332 | 0.568 | 0.236 | 2 |

| 29-September | 14.5531 | 14.9682 | 415.1 | 55 | 0.428 | 0.502 | 0.074 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dafalla, M. Using 5TE Sensors for Monitoring Moisture Conditions in Green Parks. Sensors 2024, 24, 3479. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113479

Dafalla M. Using 5TE Sensors for Monitoring Moisture Conditions in Green Parks. Sensors. 2024; 24(11):3479. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113479

Chicago/Turabian StyleDafalla, Muawia. 2024. "Using 5TE Sensors for Monitoring Moisture Conditions in Green Parks" Sensors 24, no. 11: 3479. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113479