Streaming Potential Experiment on Sandstone Core Samples Based on Current Source Model under Different Sodium Chloride Solutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Methods

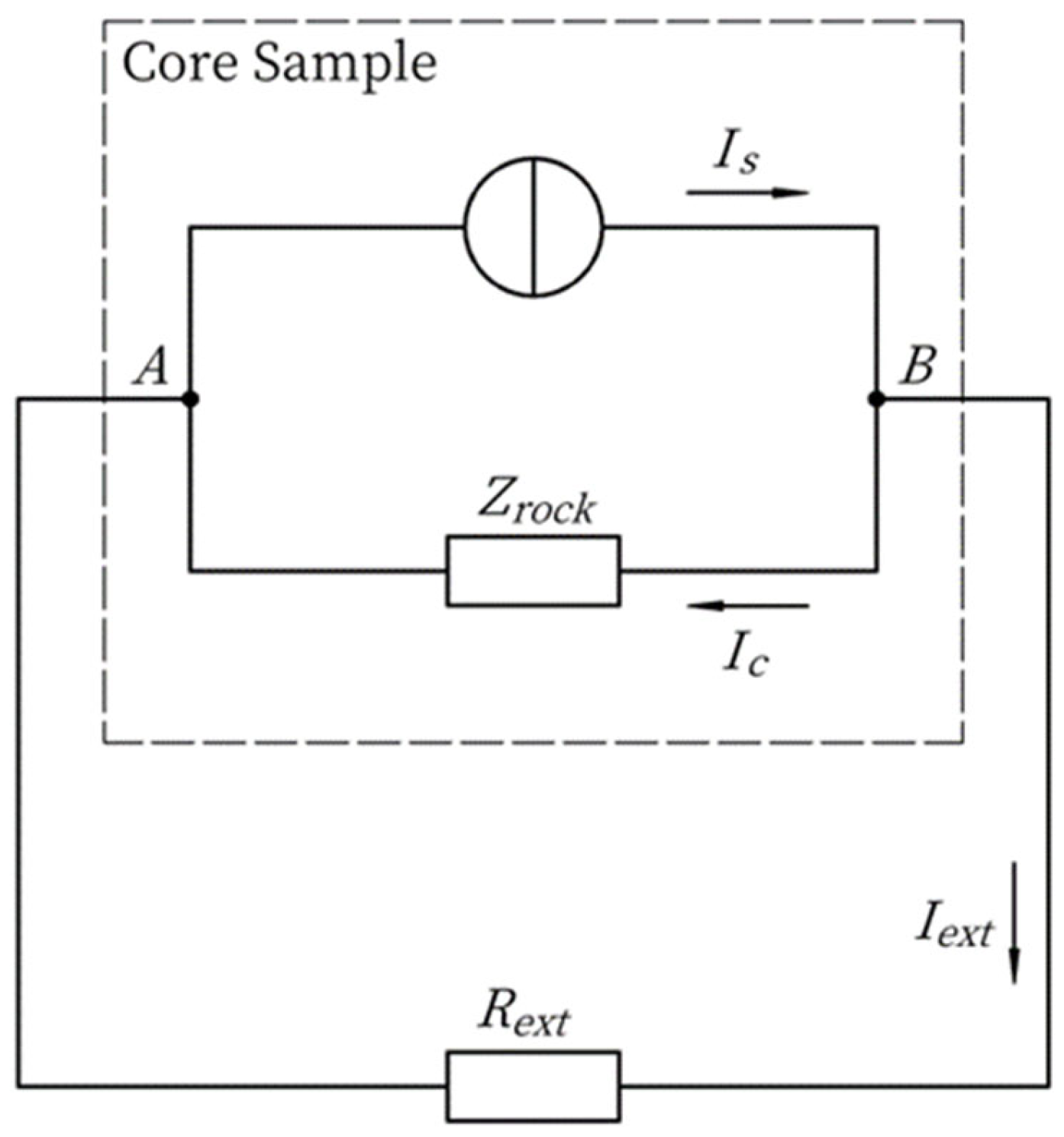

2.1. Core Current Source Model

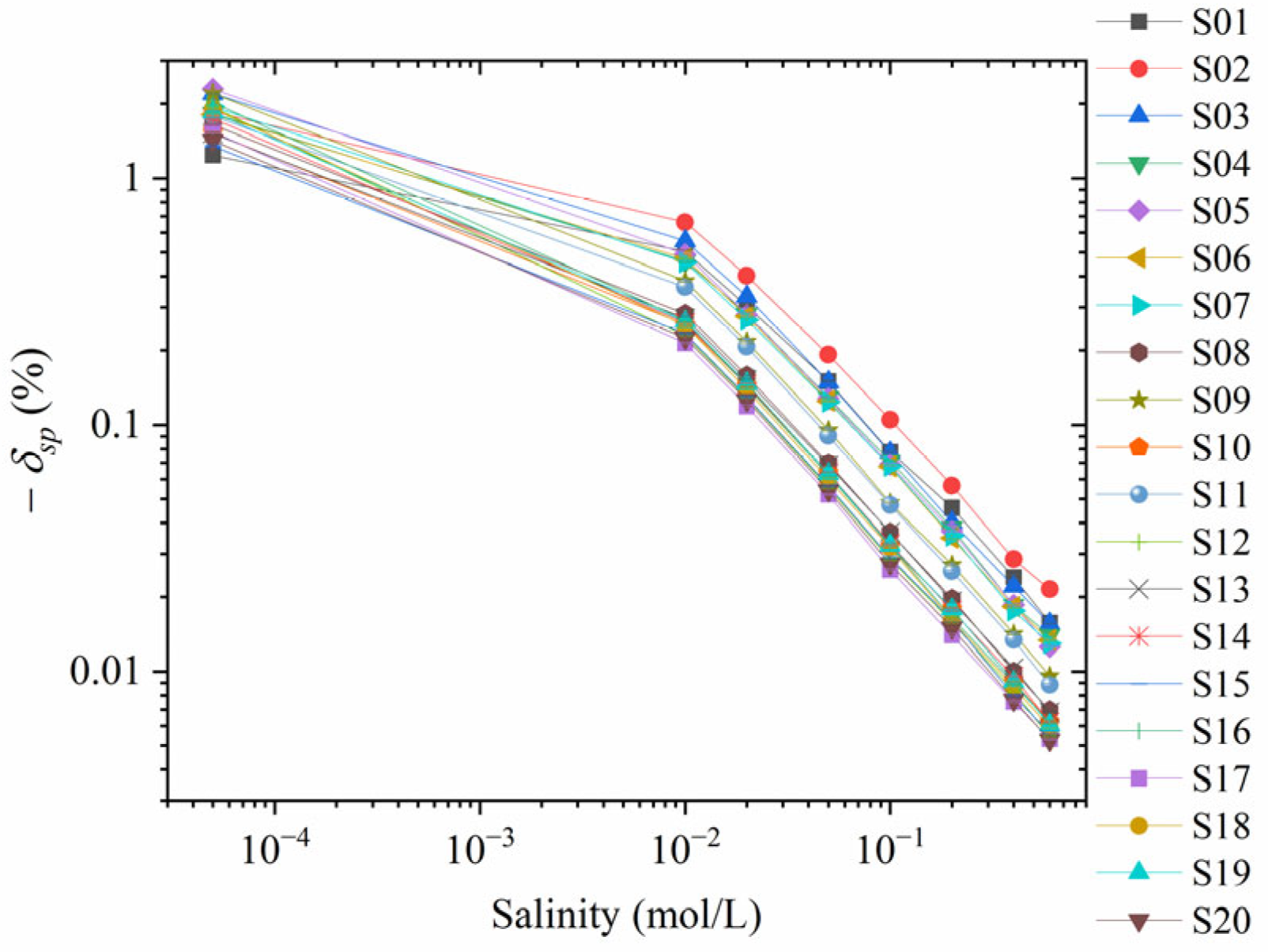

2.2. Experimental Verification of the Current Source Model

2.3. Correction of Experimental Errors

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Sample Pre-Treatment

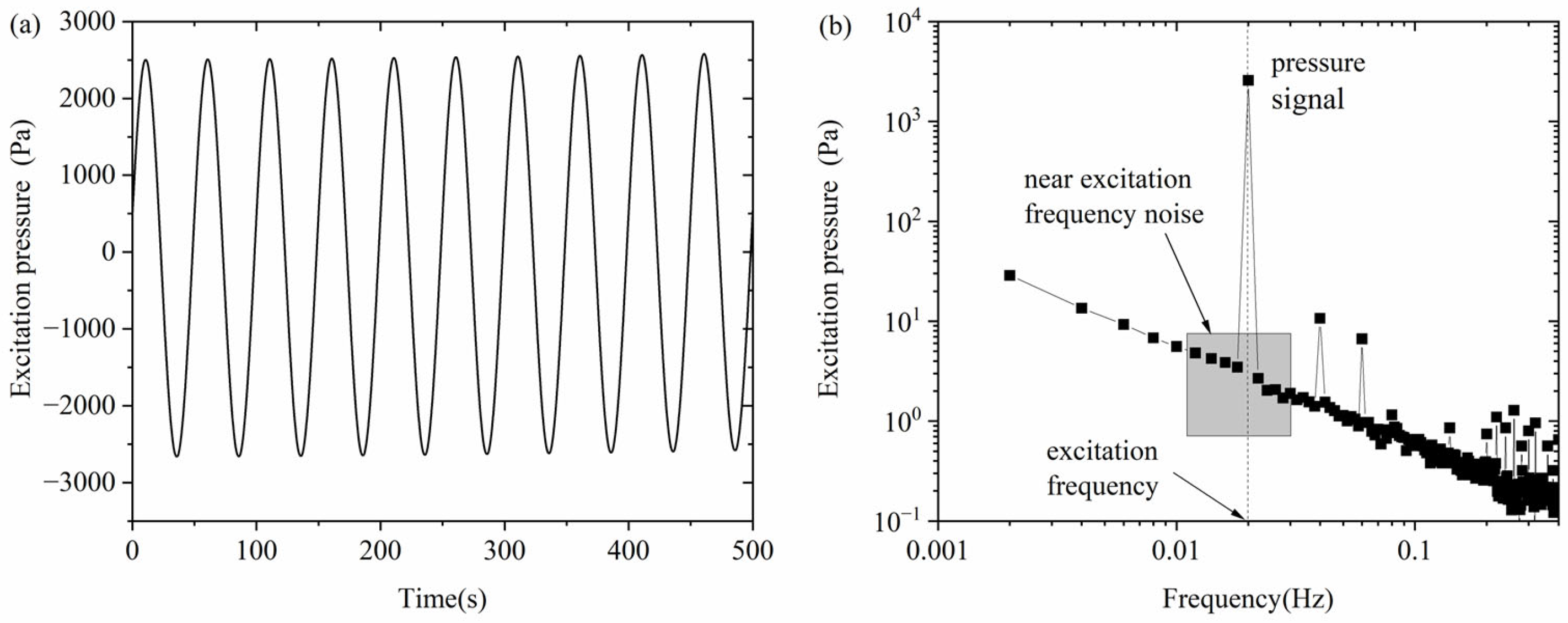

3.2. Experimental Signals

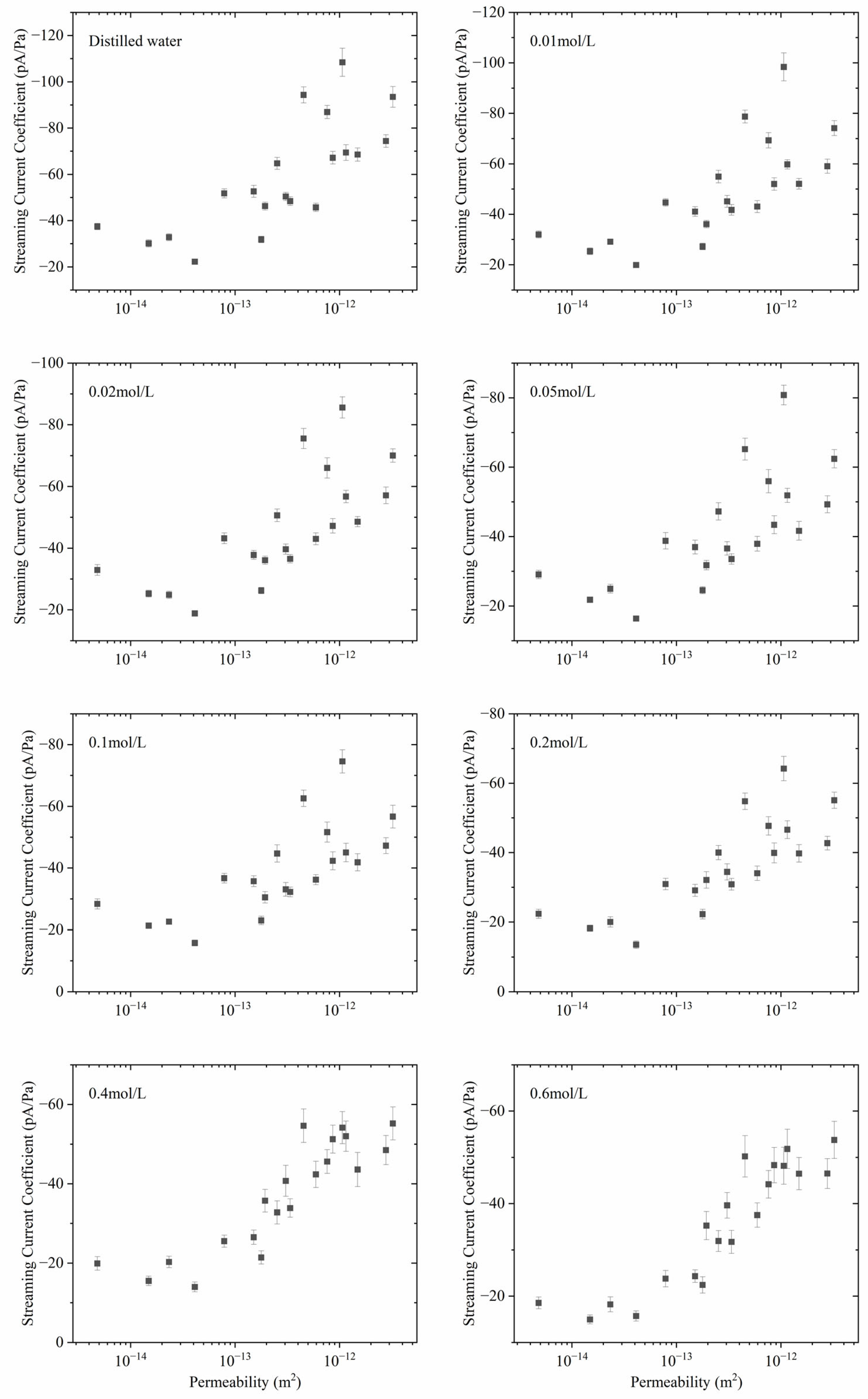

3.3. The Relationship between Streaming Current Coefficient and Permeability

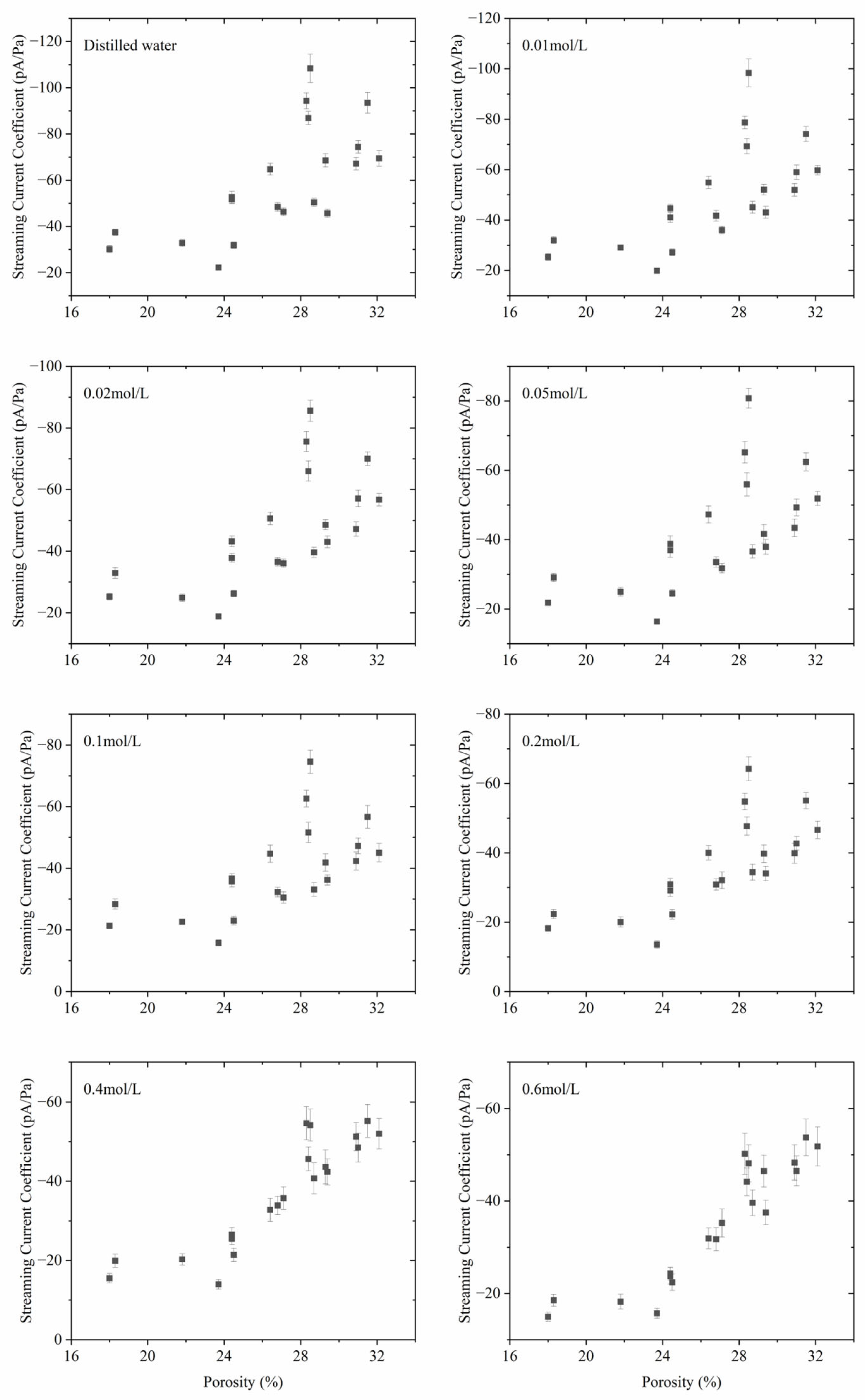

3.4. The Relationship between Streaming Current Coefficient and Porosity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Michov, B.M. A quantitative theory of the stern electric double layer. Electrophoresis 1988, 9, 201–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaafar, M.Z.; Vinogradov, J.; Jackson, M.D. Measurement of streaming potential coupling coefficient in sandstones saturated with high salinity NaCl brine. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, L21306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.; Glover, P.W.J. Measurements of the relationship between microstructure, pH, and the streaming and zeta potentials of sandstones. Transp. Porous Media 2018, 121, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouniaux, L.; Zyserman, F. A review on electrokinetically induced seismo-electrics, electro-seismics, and seismo-magnetics for Earth sciences. Solid Earth 2016, 7, 249–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.U. A laboratory study of streaming potentials. Geophys. Prospect. 1964, 12, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reppert, P.M.; Morgan, F.D. Temperature-dependent streaming potentials: 2. Laboratory. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2003, 108, 2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guan, W.; Cong, P.; Sun, Q. Effects of heterogeneous pore closure on the permeability of coal involving adsorption-induced swelling: A micro pore-scale simulation. Energy 2022, 258, 124859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, L.D.; Jougnot, D.; Do, P.V.; Ca, N.X.; Hien, N.T. A physically based model for the streaming potential coupling coefficient in partially saturated porous media. Water 2020, 12, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhao, G.; Li, N.; Zhang, J.; Jian, Y. The electrokinetic energy conversion analysis of viscoelastic fluid under the periodic pressure in microtubes. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 646, 128976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, D.; Yao, C.; Guan, W.; Hu, H.; Wen, J.; Zhang, W.; Tong, P.; Yang, Q. Simulation of seismoelectric waves using finite-difference frequency-domain method: 2-D SHTE mode. Geophys. J. Int. 2019, 216, 414–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Guan, W.; Gao, Y.; Wu, X. Experimental studies on the mechanism of seismoelectric logging while drilling with multipole source. Geophys. J. Int. 2021, 225, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levant, M.; Agenet, N.; Santanach, E. Surface Probing with Streaming Potential: The Polymer Flooding Scenario. Transp. Porous Media 2019, 130, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guan, W.; Zhao, C.; Zou, X.; He, Z.; Zhao, H. Spontaneous imbibition behavior in porous media with various hydraulic fracture propagations: A pore-scale perspective. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2023, 9, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finizola, A.; Lénat, J.F.; Macedo, O.; Ramos, D.; Thouret, J.C.; Sortino, F. Fluid circulation and structural discontinuities inside Misti volcano (Peru) inferred from self-potential measurements. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2004, 135, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulessa, B.; Murray, T.; Rippin, D. Active seismoelectric exploration of glaciers. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L07503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Wu, H. A laboratory seismoelectric measurement for the permafrost model with a frozen–unfrozen interface. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, L2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasaya, T.; Iwamoto, H.; Kawada, Y. Deep-sea DC resistivity and self-potential monitoring system for environmental evaluation with hydrothermal deposit mining. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 608381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guan, W.; Zhao, C.; Zou, X.; He, Z.; Zhao, H. A computational workflow to study CO2 transport in porous media with irregular grains: Coupling a Fourier series-based approach and CFD. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 138037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherubini, A.; Garcia, B.; Cerepi, A.; Revil, A. Influence of CO2 on the electrical conductivity and streaming potential of carbonate rocks. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2019, 124, 10056–10073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Chu, W.; Tan, J.; Guo, W. The mechanism for solar irradiation enhanced evaporation and electricity generation. Nano Energy 2022, 101, 107605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouniaux, L.; Pozzi, J.P. Permeability dependence of streaming potential in rocks for various fluid conductivities. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1995, 22, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revil, A.; Hermitte, D.; Spangenberg, E.; Cochemé, J.J. Electrical properties of zeolitized volcaniclastic materials. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2002, 107, ECV-3-1–ECV-3-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Heng, H.; Jun, W. Verification of Onsager reciprocity in low salinity with successive measurements of streaming potential and electroosmotic pressure. Chin. J. Geophys. 2019, 62, 2774–2783. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Luong, D.T.; Sprik, R. Examination of a theoretical model of streaming potential coupling coefficient. Int. J. Geophys. 2014, 2014, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherubini, A.; Garcia, B.; Cerepi, A.; Revil, A. Streaming potential coupling coefficient and transport properties of unsaturated carbonate rocks. Vadose Zone J. 2018, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, W.; Heng, H.; Wei, G. The evaluation of rock permeability with streaming current measurements. Geophys. J. Int. 2016, 206, 1563–1573. [Google Scholar]

| Number | Type | Density g/cm3 | Porosity % | Permeability ×10−15 m2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S01 | Grayish-white fine sandstone | 2.62 | 18.3 | 4.8 |

| S02 | Grayish-white fine sandstone | 2.68 | 18.0 | 14.9 |

| S03 | Grayish-white fine sandstone | 2.67 | 21.8 | 23.3 |

| S04 | Gray fine sandstone | 2.67 | 23.7 | 41.2 |

| S05 | Grayish-white medium sandstone | 2.64 | 24.4 | 78.7 |

| S06 | Grayish-white fine sandstone | 2.67 | 24.4 | 151 |

| S07 | Grayish-white fine sandstone | 2.67 | 24.5 | 178 |

| S08 | Grayish-white medium sandstone | 2.61 | 27.1 | 194 |

| S09 | Grayish-white medium sandstone | 2.63 | 26.4 | 253 |

| S10 | Grayish-white medium sandstone | 2.63 | 28.7 | 306 |

| S11 | Grayish-white medium sandstone | 2.69 | 26.8 | 337 |

| S12 | Grayish-white medium sandstone | 2.65 | 28.3 | 453 |

| S13 | Grayish-white coarse sandstone | 2.65 | 29.4 | 594 |

| S14 | Grayish-white coarse sandstone | 2.62 | 28.4 | 762 |

| S15 | Gray coarse sandstone | 2.63 | 30.9 | 862 |

| S16 | Gray coarse sandstone | 2.61 | 28.5 | 1066 |

| S17 | Grayish-white coarse sandstone | 2.61 | 32.1 | 1152 |

| S18 | Grayish-white medium sandstone | 2.65 | 29.3 | 1491 |

| S19 | Grayish-brown coarse sandstone | 2.61 | 31.0 | 2785 |

| S20 | Grayish-brown coarse sandstone | 2.62 | 31.5 | 3241 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yin, C.; Guan, W.; Hu, H. Streaming Potential Experiment on Sandstone Core Samples Based on Current Source Model under Different Sodium Chloride Solutions. Sensors 2024, 24, 3514. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113514

Yin C, Guan W, Hu H. Streaming Potential Experiment on Sandstone Core Samples Based on Current Source Model under Different Sodium Chloride Solutions. Sensors. 2024; 24(11):3514. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113514

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Chenggang, Wei Guan, and Hengshan Hu. 2024. "Streaming Potential Experiment on Sandstone Core Samples Based on Current Source Model under Different Sodium Chloride Solutions" Sensors 24, no. 11: 3514. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113514

APA StyleYin, C., Guan, W., & Hu, H. (2024). Streaming Potential Experiment on Sandstone Core Samples Based on Current Source Model under Different Sodium Chloride Solutions. Sensors, 24(11), 3514. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113514