Designing High Performance Carbon/ZnSn(OH)6-Based Humidity Sensors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Details

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of Carbon/ZnSn(OH)6

2.3. Materials Characterization

2.4. Fabrication and Measurement of Humidity Sensors

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structure and Morphology Analysis

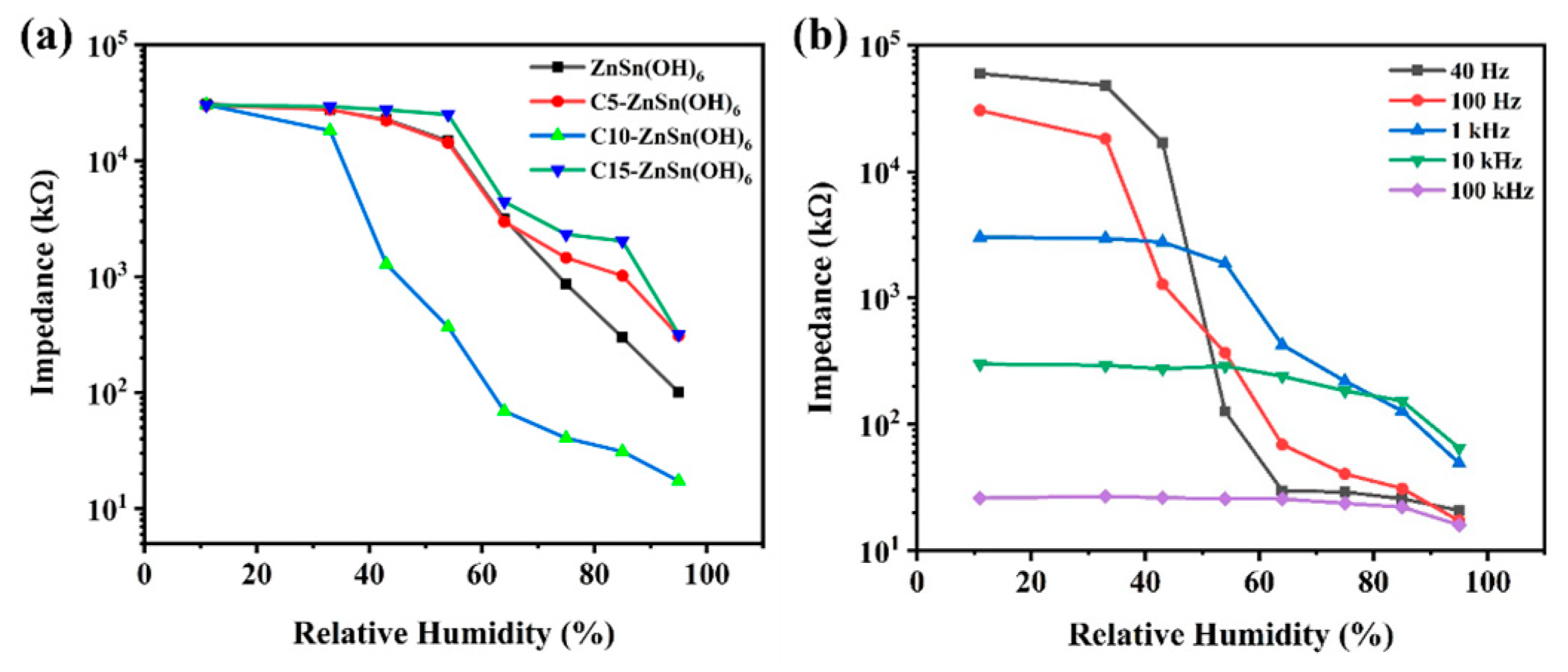

3.2. Humidity-Sensitive Performance

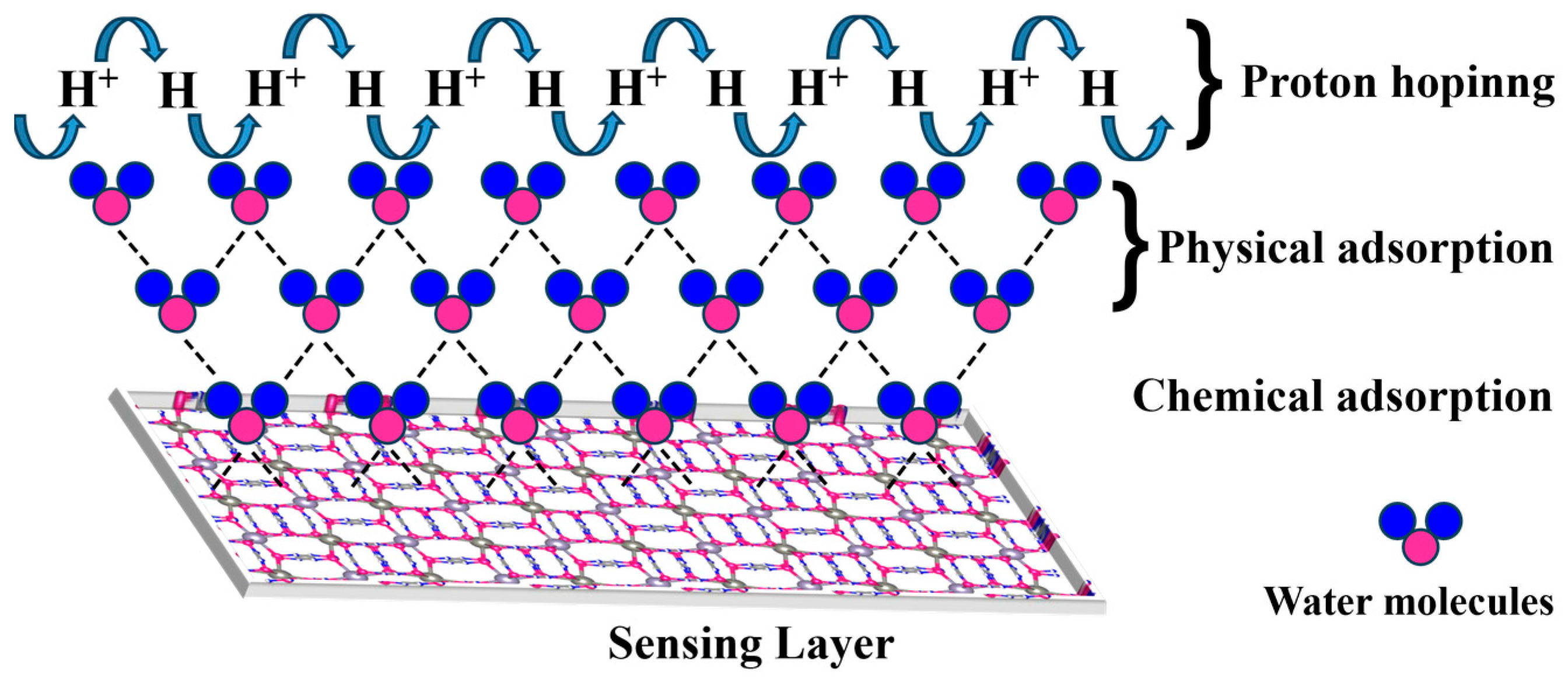

3.3. Mechanistic Analysis of the Sensors

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, K.; Fujita, Y.; Lu, Y.; Honda, S.; Shiomi, M.; Arie, T.; Akita, S.; Takei, K. A wearable body condition sensor system with wireless feedback alarm functions. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2008701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, L.; Yu, T.; Zhao, D.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Xu, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhao, H.; Gao, Y. In situ deposited hierarchical CuO/NiO nanowall arrays film sensor with enhanced gas sensing performance to H2S. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 385, 121570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hui, Z.; Zhou, J.; Huang, X.; Sun, G.; Huang, W. Ti3C2TX MXene for sensing applications: Recent progress, design principles, and future perspectives. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 3996–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galstyan, V.; Poli, N.; D’Arco, A.; Macis, S.; Lupi, S.; Comini, E. A novel approach for green synthesis of WO3 nanomaterials and their highly selective chemical sensing properties. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 20373–20385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Chauhan, V.; Ram, J.; Gupta, R.; Kumar, S.; Chaudhary, P.; Yadav, B.C.; Ojha, S.; Sulania, I.; Kumar, R. Study of humidity sensing properties and ion beam induced modifications in SnO2-TiO2 nanocomposite thin films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 392, 125768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yu, X.; Xiong, X.; Li, S.; Jin, T.; Chen, Y. Enhancing anti-thermal hysteresis ability, response stability and sensitivity of polymer humidity sensor by in-situ crosslinking curing method. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e53868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Li, J.; Yuan, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Tai, H. Capacitive humidity sensor based on zirconium phosphate nanoplates film with wide sensing range and high response. Sens. Actuators B 2023, 394, 134445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Wei, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Qian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, F.; Chen, G. Porous and conductive cellulose nanofiber/carbon nanotube foam as a humidity sensor with high sensitivity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 292, 119684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, M.; Yang, L.; Wu, R.; Wu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Liu, Y. The effect of surface hydroxyls on the humidity-sensitive properties of LiCl-doped ZnSn(OH)6 sphere-based sensors. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastgeer, G.; Shahzad, Z.M.; Chae, H.; Kim, Y.H.; Ko, B.M.; Eom, J. Bipolar junction transistor exhibiting excellent output characteristics with a prompt response against the selective protein. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2204781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Nisar, S.; Kim, D.-k.; Golovynskyi, S.; Imran, M.; Dastgeer, G.; Wang, L. Polarization-sensitive photodetection of anisotropic 2D black arsenic. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 9076–9082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Cao, J.-j.; Li, H.; Ho, W.; Lee, S.C. Constructing Z-scheme SnO2/N-doped carbon quantum dots/ZnSn(OH)6 nanohybrids with high redox ability for NOx removal under VIS-NIR light. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 15782–15793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juang, F.-R.; Chern, W.-C.; Chen, B.-Y. Carbon dioxide gas sensing properties of ZnSn(OH)6-ZnO nanocomposites with ZnO nanorod structures. Thin Solid Films 2018, 660, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, W.; Qi, Y.; Qu, H.; Xu, J. Synthesis of a hybrid zinc hydroxystannate/reduction graphene oxide as a flame retardant and smoke suppressant of epoxy resin. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2016, 126, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, Z. The composite of ZnSn(OH)6 and Zn–Al layered double hydroxides used as negative material for zinc–nickel alkaline batteries. Ionics 2018, 24, 2035–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Song, P.; Han, D.; Yan, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Q. Controllable synthesis of novel ZnSn(OH)6 hollow polyhedral structures with superior ethanol gas-sensing performance. Sens. Actuators B 2015, 209, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Ramgir, N.; Mukherji, S.; Rao, V.R. PVA modified ZnO nanowire based microsensors platform for relative humidity and soil moisture measurement. Sens. Actuators B 2017, 253, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, X.; Yu, F.; Fan, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Xiang, Q.; Duan, Z.; Xu, J. Superhydrophilic ZnO nanoneedle array: Controllable in situ growth on QCM transducer and enhanced humidity sensing properties and mechanism. Sens. Actuators B 2018, 263, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Huang, D.; Qin, Y.; Li, L.; Jiang, X.; Chen, S. Effects of preparation method on the microstructure and photocatalytic performance of ZnSn(OH)6. Appl. Catal. B 2014, 148, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, D.; He, M.; Hu, Y.; Ruan, H.; Lin, Y.; Hu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Shao, Y. High photocatalytic performance of zinc hydroxystannate toward benzene and methyl orange. Appl. Catal. B 2012, 113, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, Z.; Si, X.; Tong, H.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Huo, J.; Cheng, G.; Du, Z. Facile synthesis of Pt catalysts functionalized porous ZnO nanowires with enhanced gas-sensing properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 947, 169486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Wang, X.; Zang, J. Ultrasensitive ethanol sensor based on nano-Ag&ZIF-8 co-modified SiNWs with enhanced moisture resistance. Sens. Actuators B 2021, 340, 129959. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, X.; Yu, X.; Du, P.; Li, N.; Chen, X. Humidity-sensitive properties of TiO2 nanorods grown between electrodes on Au interdigital electrode substrate. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 17, 6148–6152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, J. Single-layer graphene based resistive humidity sensor enhanced by graphene quantum dots. Nanotechnology 2024, 35, 185503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolahdouz, M.; Xu, B.; Nasiri, A.F.; Fathollahzadeh, M.; Manian, M.; Aghababa, H.; Wu, Y.; Radamson, H.H. Carbon-related materials: Graphene and carbon nanotubes in semiconductor applications and design. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Luo, H.; Xu, B.; Zou, X.; Zheng, X.; Ye, B.; Yu, X. Shape-controlled synthesis of ZnSn(OH)6 crystallites and their HCHO-sensing properties. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 3380–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Jung, U.; Jung, B.; Park, J.; Naushad, M. Zinc hydroxystannate/zinc-tin oxide heterojunctions for the UVC-assisted photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange and tetracycline. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 316, 120353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Jia, X.; Ma, Z.; Li, Y.; Yue, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J. W5+–W5+ Pair Induced LSPR of W18O49 to Sensitize ZnIn2S4 for Full-Spectrum Solar-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2203638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yuan, X.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, G.; Tu, W.; Sheng, C.; Deng, Y.; Chen, F.; Chew, J.W. Plasmonic Bi nanoparticles and BiOCl sheets as cocatalyst deposited on perovskite-type ZnSn(OH)6 microparticle with facet-oriented polyhedron for improved visible-light-driven photocatalysis. Appl. Catal. B 2017, 209, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Ge, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Wang, X.; Huo, M.; Lu, Y. Facile synthesis of Bi-modified Nb-doped oxygen defective BiOCl microflowers with enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic performance. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 786, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, E.; Mohamed, S.; Samy, M.; Mensah, K.; Ossman, M.; Elkady, M.F.; Hassan, H.S. Catalytic fabrication of graphene, carbon spheres, and carbon nanotubes from plastic waste. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 1977–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose, M.; Nithya, G.; Robert, R.; Dhas, S.A.M.B. Formation and optical characterization of unique zinc hydroxy stannate nanostructures by a simple hydrothermal method. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 2628–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillip, G.R.; Nagajyothi, P.C.; Ramaraghavulu, R.; Banerjee, A.N.; Reddy, B.V.; Joo, S.W. Synthesis of crystalline zinc hydroxystannate and its thermally driven amorphization and recrystallization into zinc orthostannate and their phase-dependent cytotoxicity evaluation. Mater. Chem. Phys 2020, 248, 122946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zi, J.; Huang, B.; Yan, L.; Fa, W.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, Z. Controlled growth and thermal decomposition of well-dispersed and uniform ZnSn(OH)6 submicrocubes. J. Alloy. Compd. 2014, 607, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Li, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, F.; Zhao, H. 2D SnO2 nanosheets: Synthesis, characterization, structures, and excellent sensing performance to ethylene glycol. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paeng, C.; Shanmugasundaram, A.; We, G.; Kim, T.; Park, J.; Lee, D.-W.; Yim, C. Rapid and flexible humidity sensor based on laser-induced graphene for monitoring human respiration. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 4772–4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wan, H.; Lin, Q. Properties of a nanocrystalline barium titanate on silicon humidity sensor. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2003, 14, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, H.; Chen, C.; Lin, C. Investigation of humidity sensor based on Au modified ZnO nanosheets via hydrothermal method and first principle. Sens. Actuators B 2019, 287, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, U.; Dhanasekar, M.; Kadrekar, R.; Arya, A.; Bhat, S.V.; Late, D.J. Efficient humidity sensor based on surfactant free Cu2ZnSnS4 nanoparticles. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 28898–28905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Kumar, K.; Saeed, S.H.; Pandey, N.K.; Verma, V.; Singh, P.; Yadav, B.C. Influence of tin doping on the liquefied petroleum gas and humidity sensing properties of NiO nanoparticles. J. Mater. Res. 2022, 37, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Wu, J.-F.; Lin, H.-M. Synthesis of PANIHCl/ZnO conductive composite by in-situ polymerization and for humidity sensing application. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, T.; Qi, R.; Dai, J.; Liu, S.; Fei, T.; Lu, G. Organic-inorganic hybrid materials based on mesoporous silica derivatives for humidity sensing. Sens. Actuators B 2017, 248, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomer, V.K.; Duhan, S.; Sharma, A.K.; Malik, R.; Nehra, S.P.; Devi, S. One pot synthesis of mesoporous ZnO–SiO2 nanocomposite as high performance humidity sensor. Colloids Surf. A 2015, 483, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Jia, Q.-x.; Zhang, Z. Sulfonated hypercross-linked porous organic polymer based humidity sensor. Sens. Actuators B 2024, 401, 134997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Measurement Range | Tresponse | Trecovery | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SnO2-TiO2 | 11–95% RH | 19.1 s | 181 s | [5] |

| c-IPN polymer | 30–90% RH | 38 s | 70 s | [6] |

| Cu2ZnSnS4 | 11–97% RH | 105 s | 36 s | [39] |

| Sn-doped NiO | 10–90% RH | 43 s | 38 s | [40] |

| PANIHCl/ZnO | 10–90% RH | 13 s | 171 s | [41] |

| C10-ZnSn(OH)6 | 11–95% RH | 3.2 s | 24.4 s | This work |

| Relative Humidity | 11% RH | 33% RH | 43% RH | 54% RH | 64% RH | 75% RH | 85% RH | 95% RH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall error rate | 1.17% | 1.29% | 2.09% | 1.83% | 0.91% | 0.38% | 0.25% | 0.87% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Jia, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z. Designing High Performance Carbon/ZnSn(OH)6-Based Humidity Sensors. Sensors 2024, 24, 3532. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113532

Zhang M, Jia H, Wang S, Zhang Z. Designing High Performance Carbon/ZnSn(OH)6-Based Humidity Sensors. Sensors. 2024; 24(11):3532. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113532

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Min, Hongguang Jia, Shuying Wang, and Zhenya Zhang. 2024. "Designing High Performance Carbon/ZnSn(OH)6-Based Humidity Sensors" Sensors 24, no. 11: 3532. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113532

APA StyleZhang, M., Jia, H., Wang, S., & Zhang, Z. (2024). Designing High Performance Carbon/ZnSn(OH)6-Based Humidity Sensors. Sensors, 24(11), 3532. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113532