Sensors Layout Optimization Design of Rocket Sled Test System

Abstract

:1. Introduction

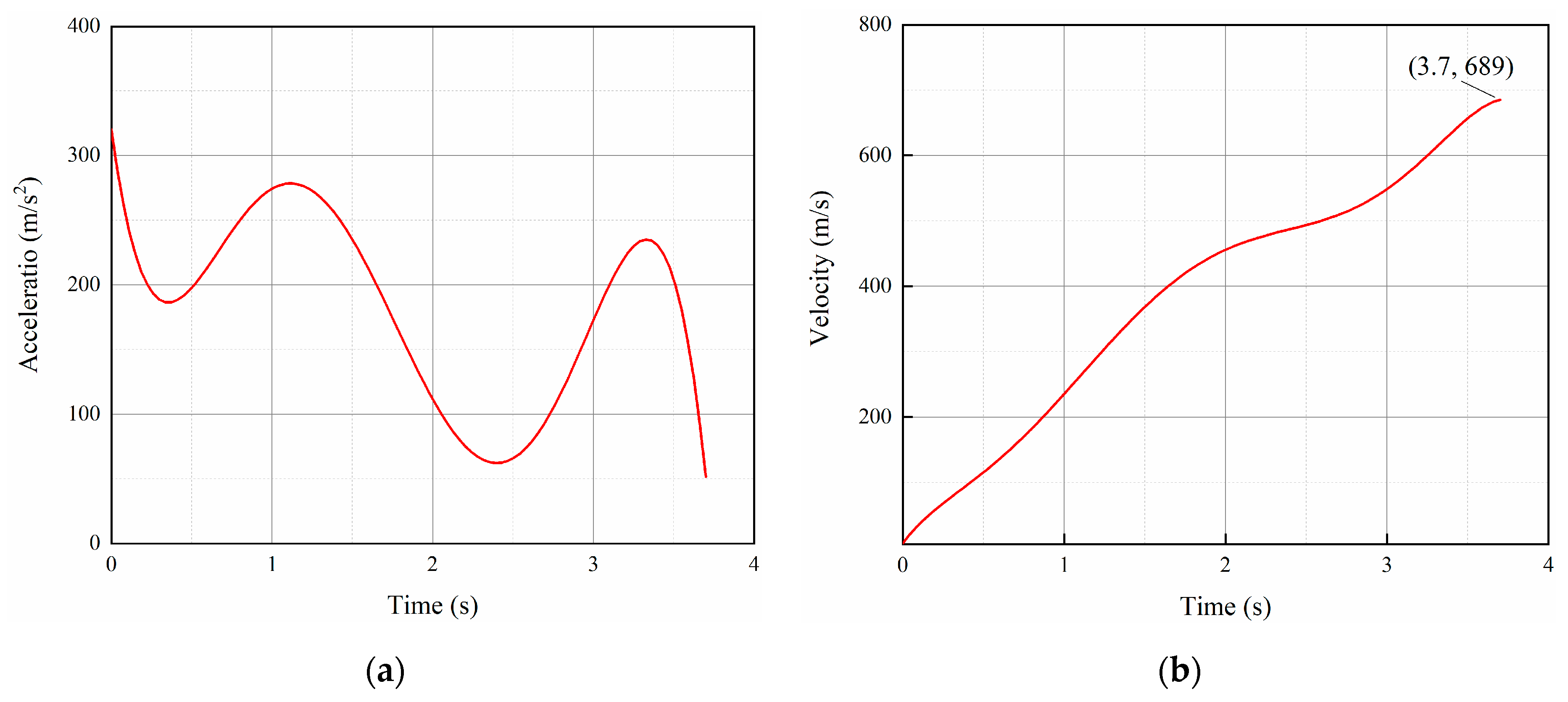

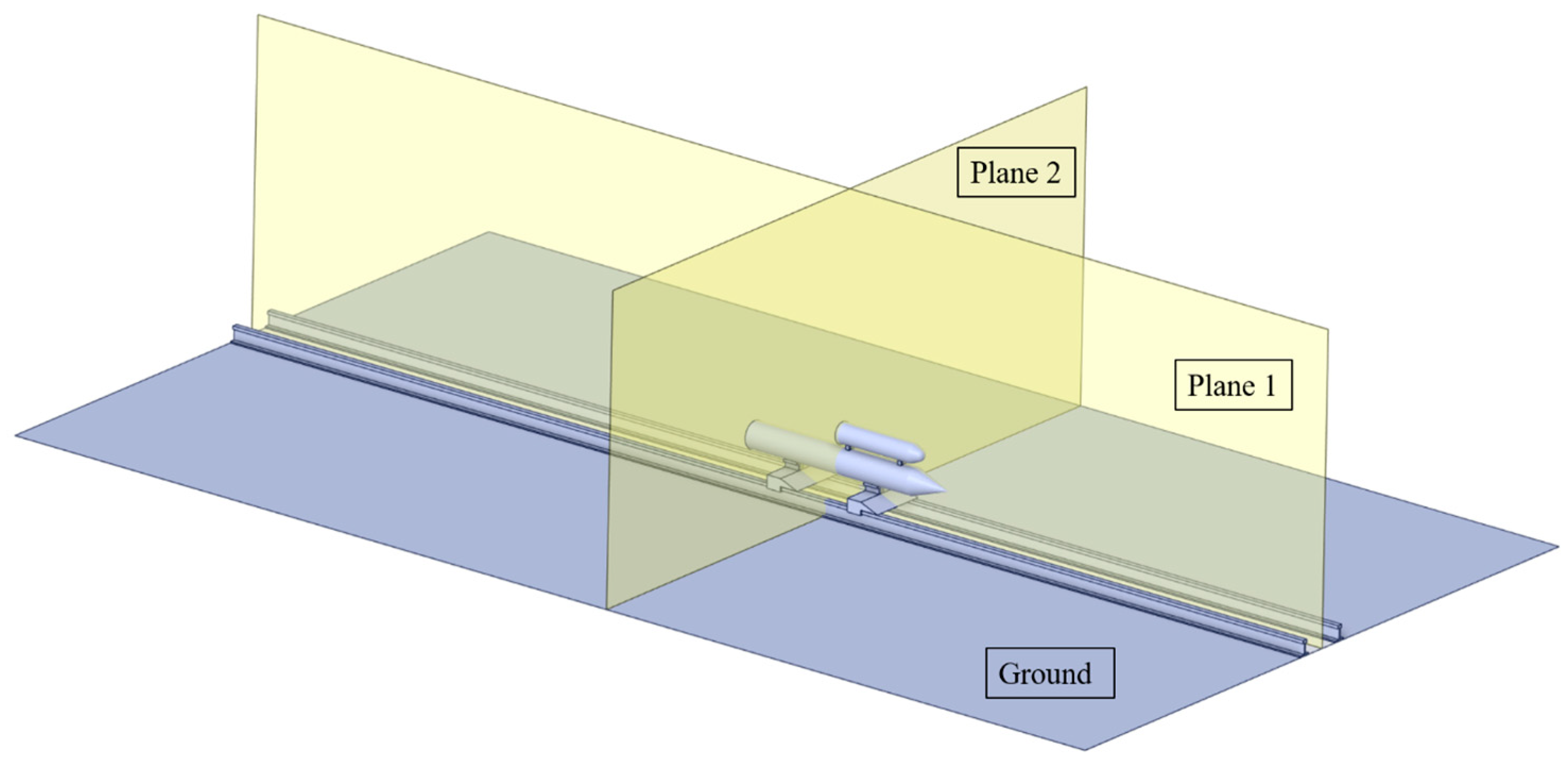

2. Model Setup

3. Computational Methods and Validations

3.1. Numerical Method

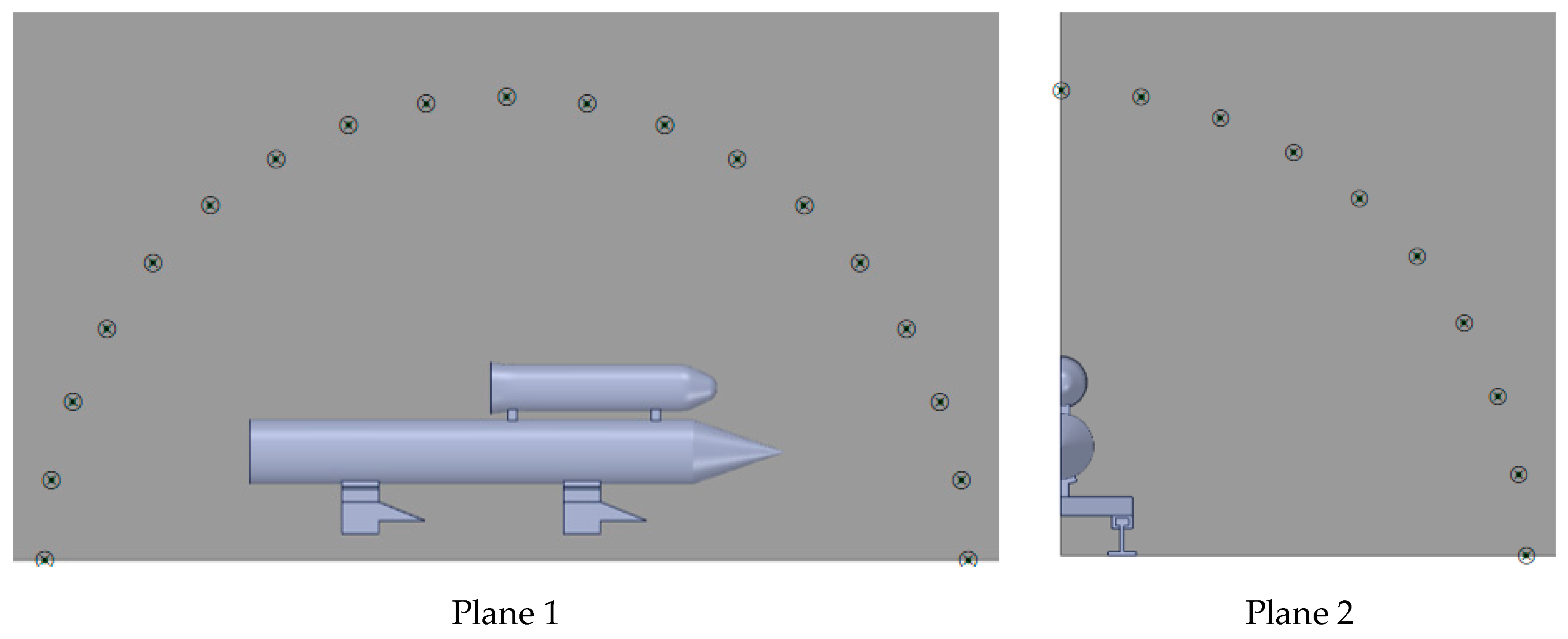

3.2. Computational Grid and Boundary Conditions

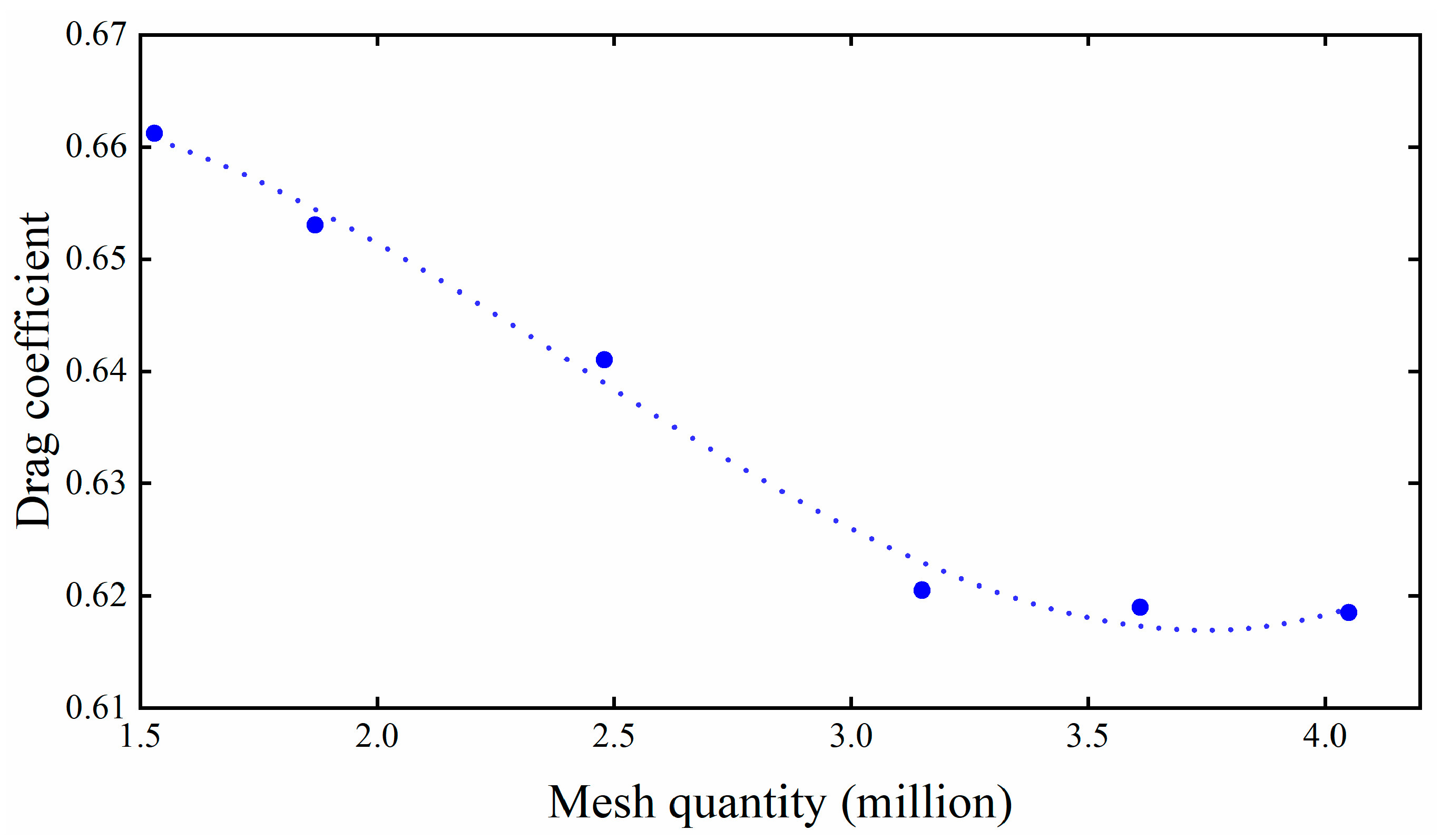

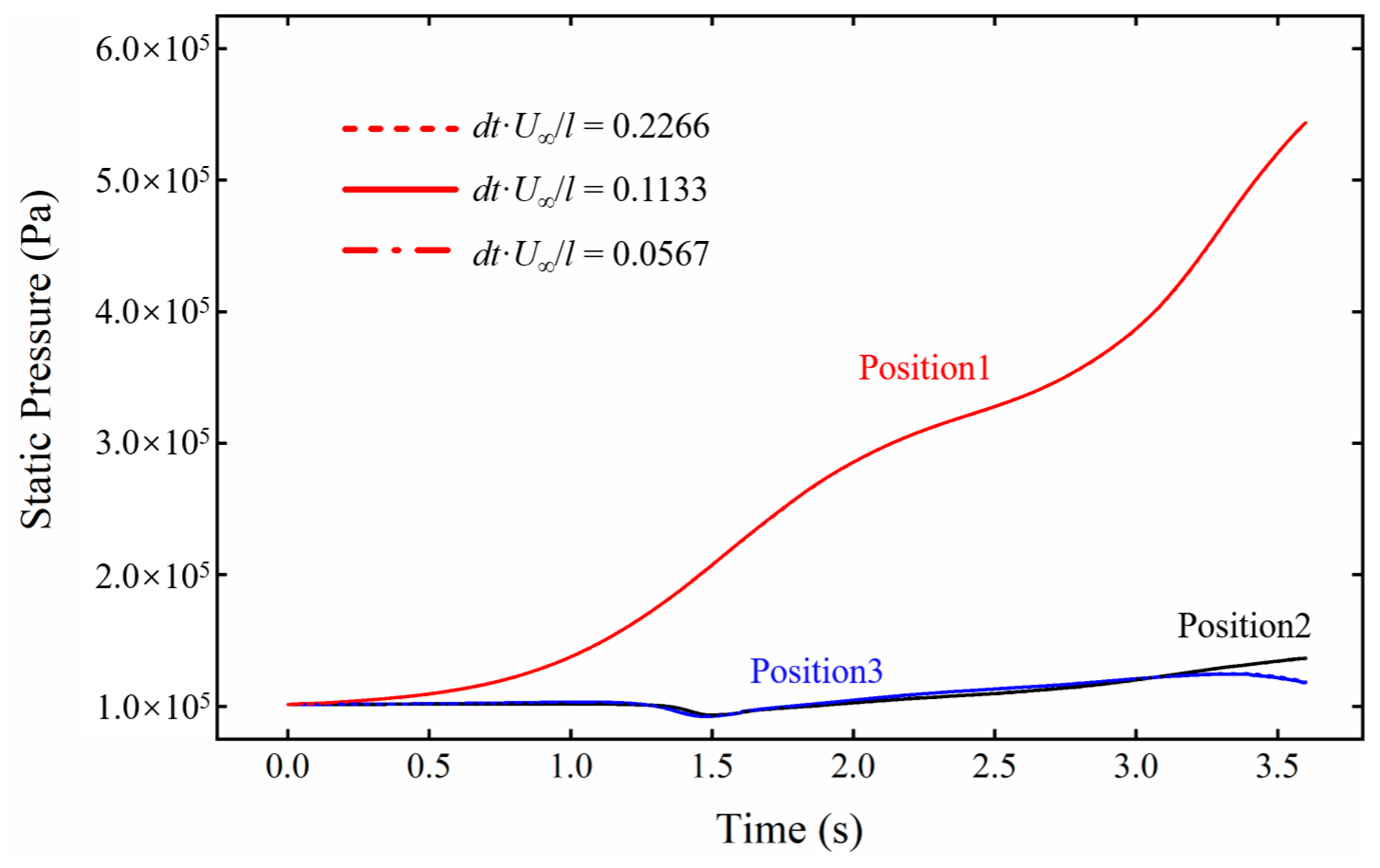

3.3. Grid and Time Step Independence

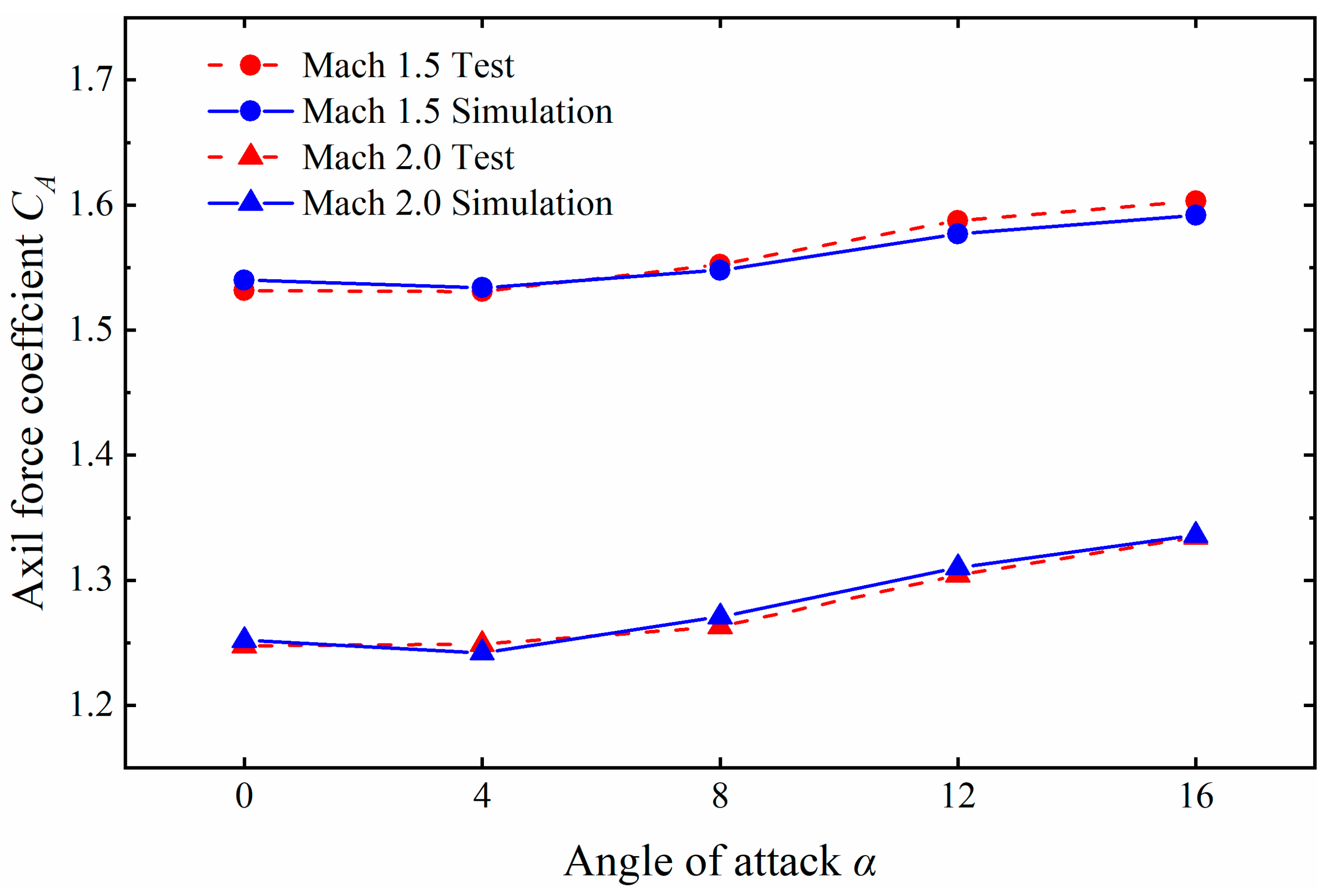

3.4. Validation of Numerical Methods

4. Results and Discussions

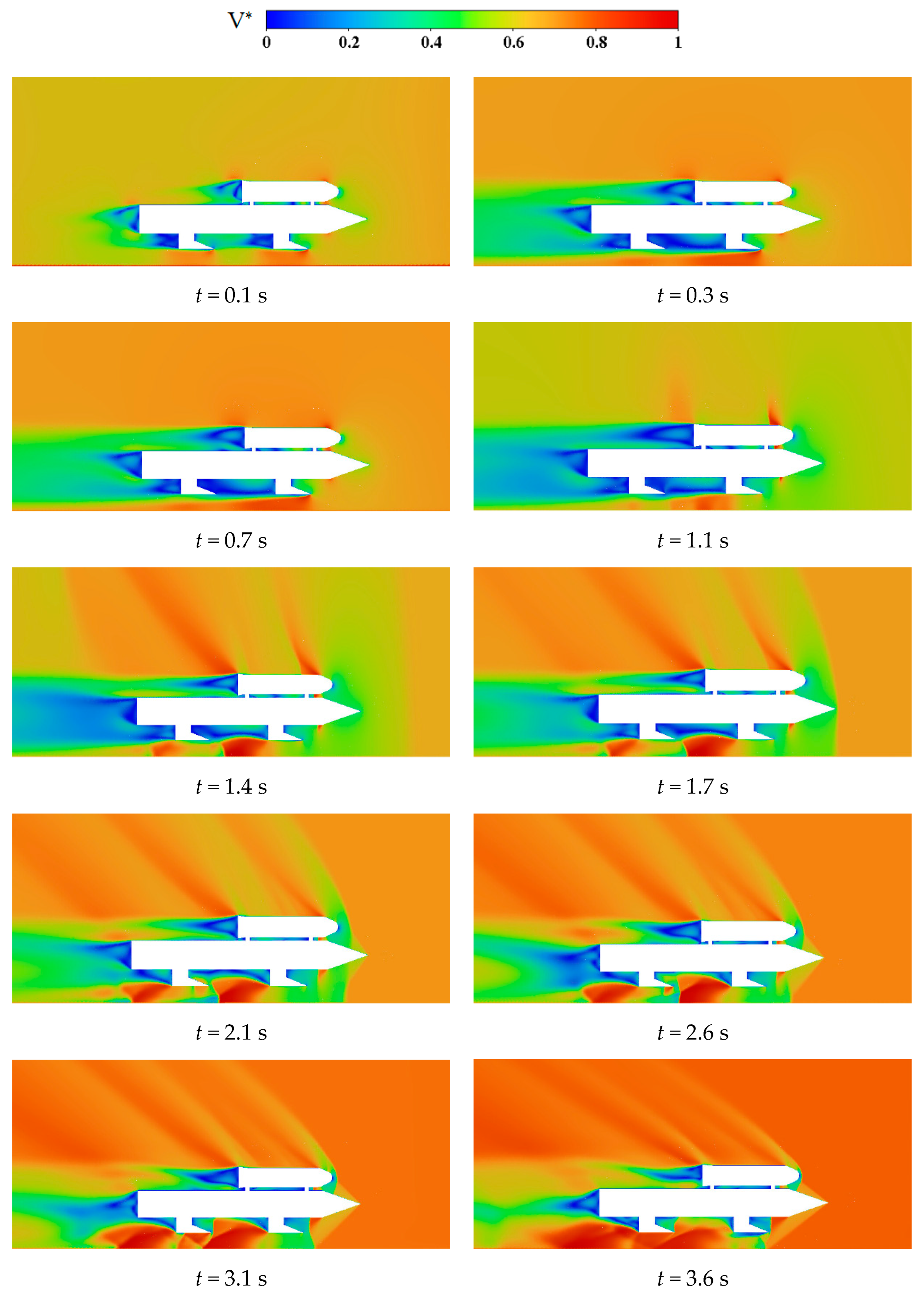

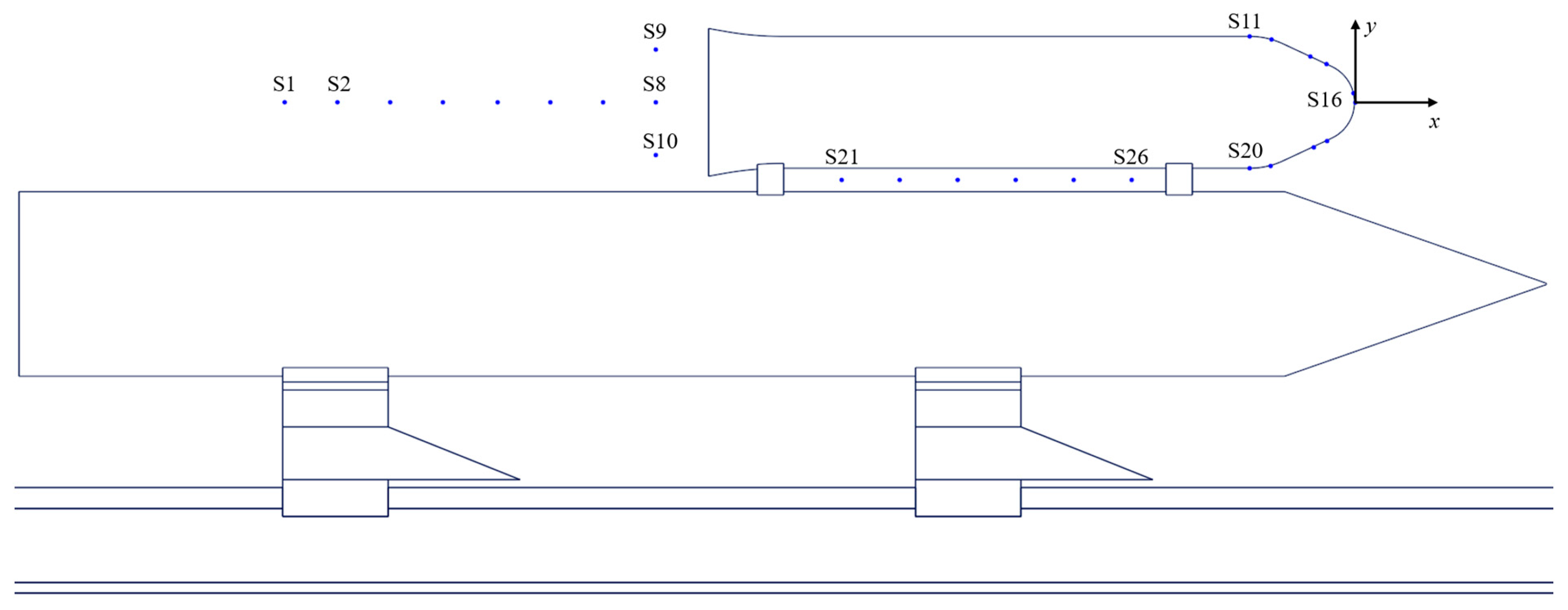

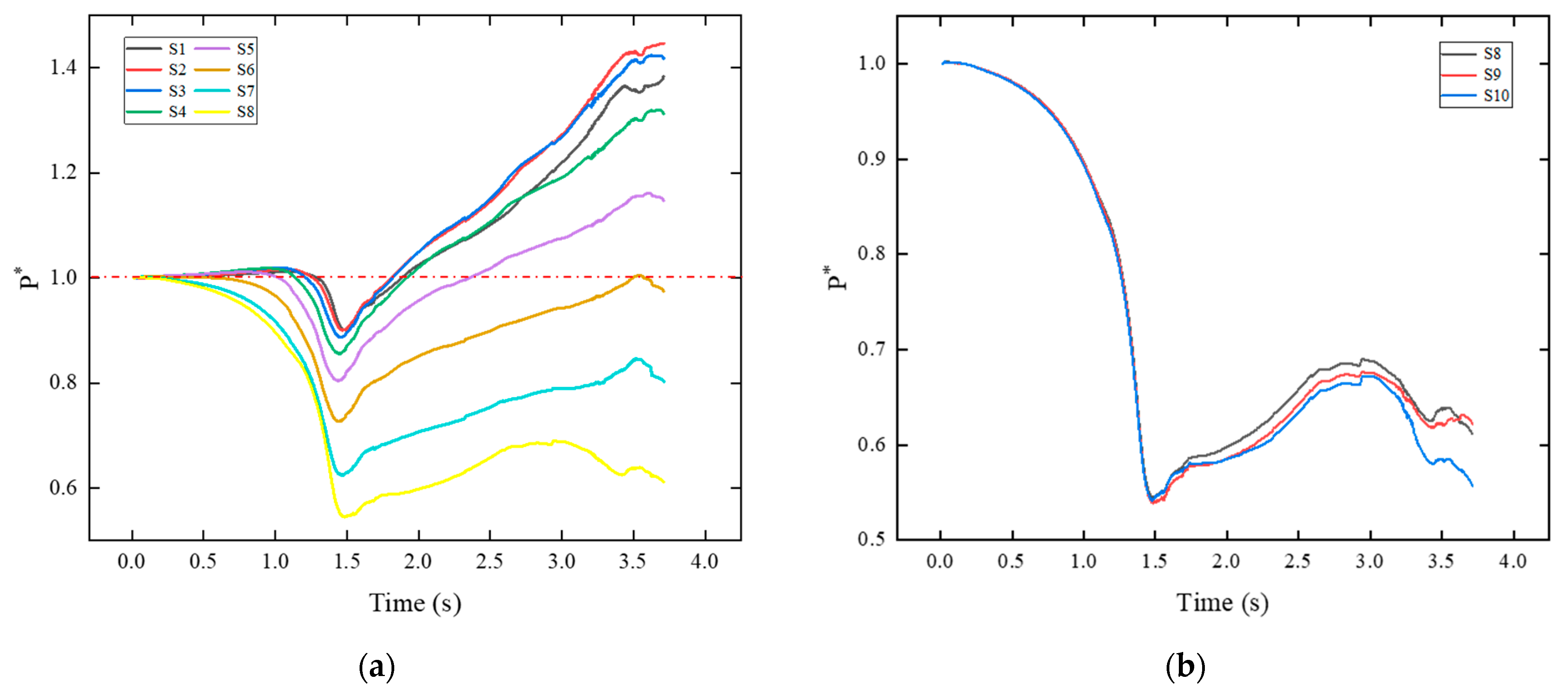

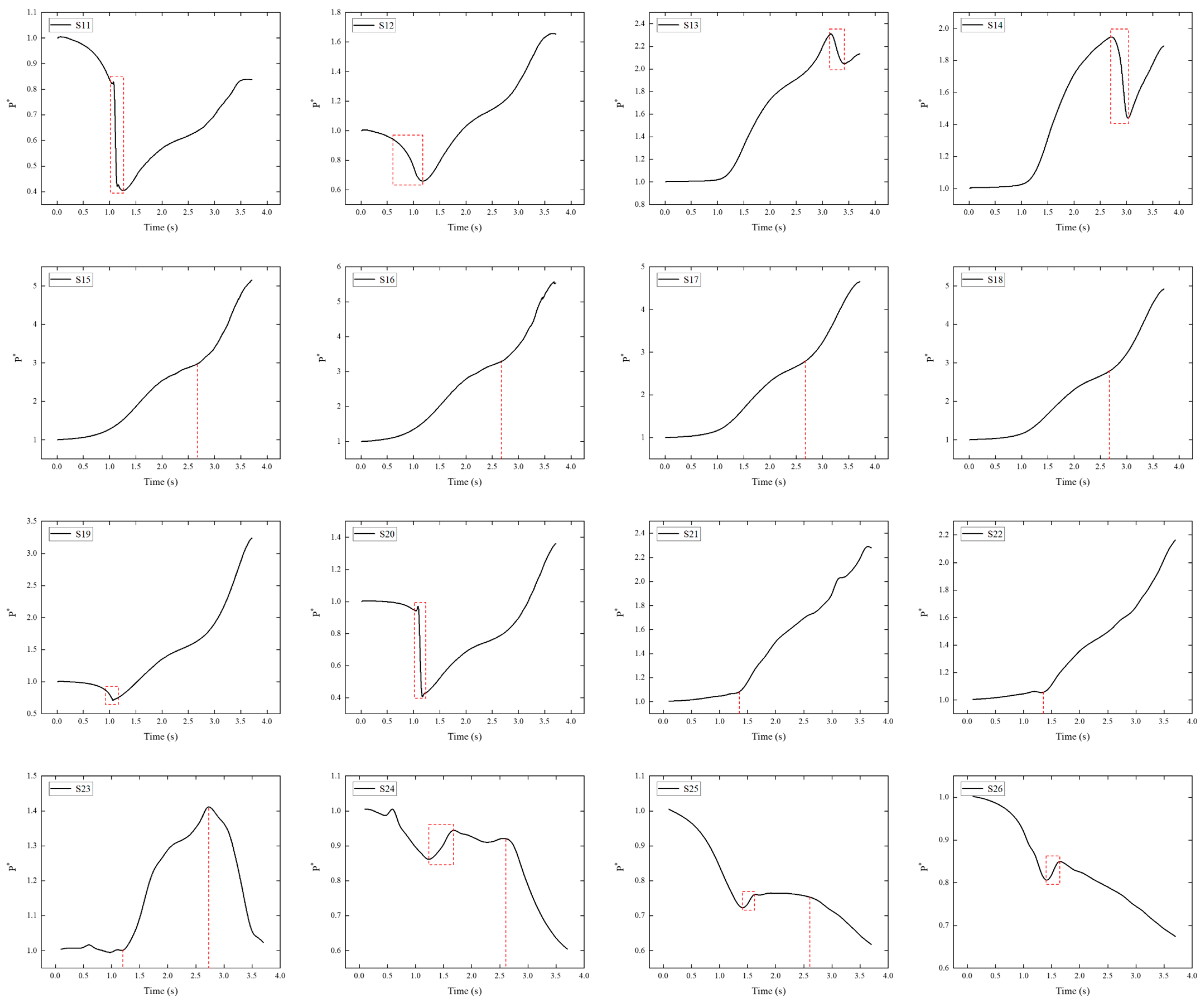

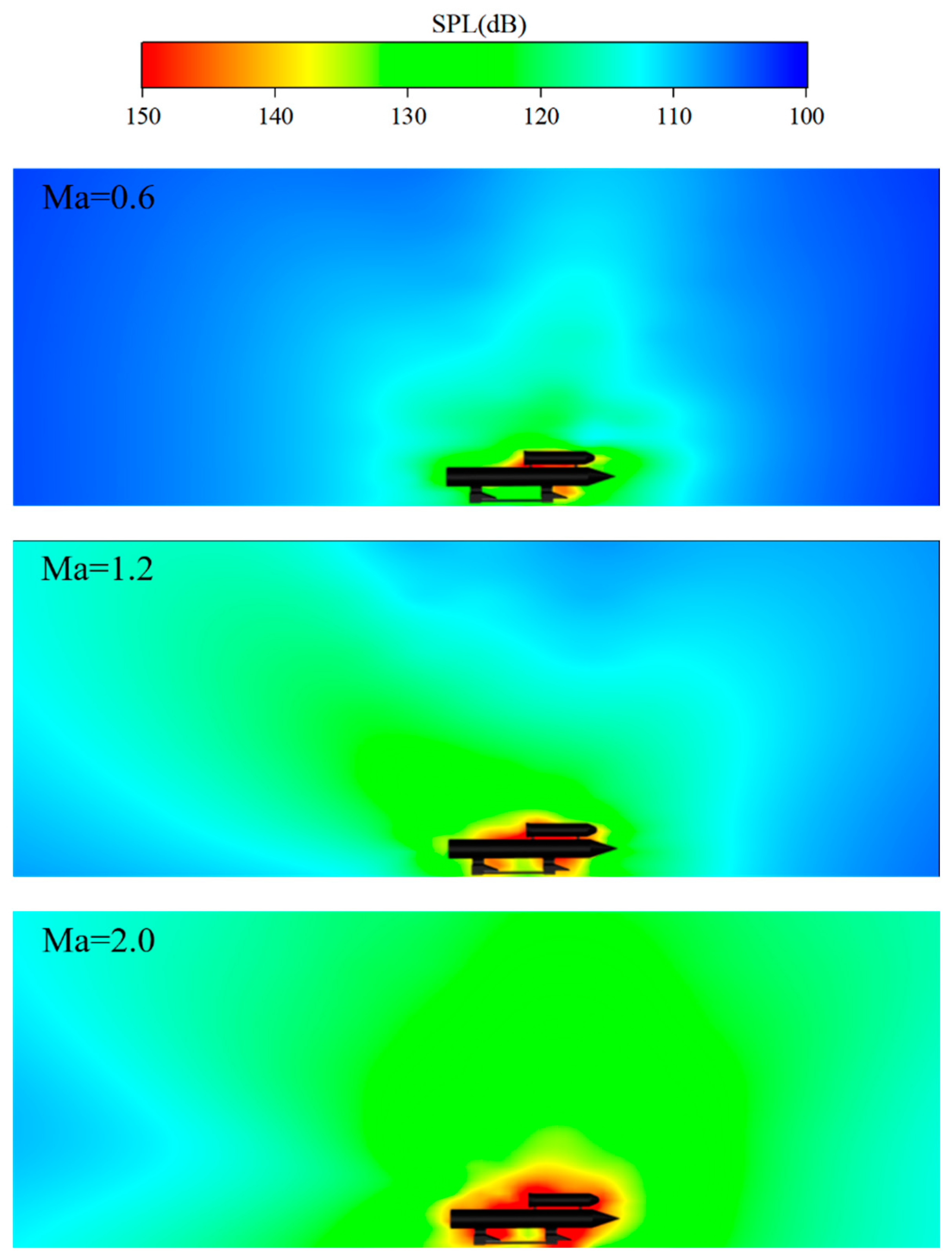

4.1. Flow Field Analysis and Sensors Layout

4.2. Aeroacoustic Characteristics of Variable Acceleration Rocket Sled

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J. The Research for Coupled Dynamics of High Speed Rocket Sled-Track Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanjing University of Science & Technology, Nanjing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, K.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z. Research on Structure Dynamic Simulation Analysis Technology of Rocket Sled. Navig. Control. 2015, 6, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, N.L. Reverse Velocity Rocket Sled Test Bed for Inertial Guidance Systems. Navigation 1983, 30, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. XB High Accuracy Rocket Sled Test Track. Eng. Sci. 2000, 2, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, D.; Gallon, J.C.; Hennings, E.J.; Johnson, M.R.; Marti, B.; Meacham, M.B.; Natzic, D.B.; Rivellini, T.; Tanner, C.L.; Thompson, N.B. Rocket Sled Strength Testing of Large, Supersonic Parachutes. In Proceedings of the 23rd AIAA Aerodynamic Decelerator Systems Technology Conference, Daytona Beach, FL, USA, 30 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, X.; Yang, L.; Li, H.; Xiang, Y. Study on Aerodynamic Mechanism of Strong Ground Effect on Horizontal Boost Run Cross Velocity Domain. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2023, 44, 225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Rigali, D.J.; Feltz, L.V. High-Speed Monorail Rocket Sleds for Aerodynamic Testing at High Reynolds Numbers. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 1968, 5, 1341–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, G.; Hooser, M.; Black, D.; Leader, A. Exploration of Dynamic Rocket Sled Modeling Parameters at Holloman High Speed Test Track. In U.S. Air Force T&E Days 2009; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, S.S. Definition of Boundary Conditions and Dynamic Analysis of Rocket Sled and Turntable. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2011, 52–54, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Dynamic Coupling Analysis of Rocket Propelled Sled Using Multibody-Finite Element Method. Math. Comput. Model. 2014, 18, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hooser, M. Soft Sled—The Low Vibration Sled Test Capability at the Holloman High Speed Test Track. In Proceedings of the 2018 Aerodynamic Measurement Technology and Ground Testing Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 25–29 June 2018; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Terrazas, J.; Kotteda, V.M.K.; Kumar, V.; Edmonds, R.; Zeisset, M. The CFD Modeling of the Water Braking Phenomena for the Holloman High-Speed Test Track. In Volume 1: Fluid Mechanics; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Zheng, J.; Yu, Y.; Lv, R.; Xu, C. Shock-Wave/Rail-Fasteners Interaction for Two Rocket Sleds in the SupersonicFlow Regime. Fluid Dyn. Mater. Process. 2020, 16, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, K.; Kato, Y.; Ishihara, K.; Matsuoka, K.; Kasahara, J.; Matsuo, A.; Funaki, I.; Nakata, D.; Higashino, K.; Tanatsugu, N. Thrust Validation of Rotating Detonation Engine System by Moving Rocket Sled Test. J. Propuls. Power 2021, 37, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Jiang, Y.; Pu, P. Numerical Simulation of Aerodynamic and Aeroacoustic Characteristics of Subsonic Rocket Sled. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 182, 108208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yan, H.; Chen, C.; Yu, Y. Mechanistic Study of Rail Gouging during Hypersonic Rocket Sled Tests. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 7165240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, B.; Xu, C.; Sun, J. Aerodynamic Characteristics of Supersonic Rocket-Sled Involving Waverider Geometry. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.D.; Lindsay, E.E. Force Tests of Standard Hypervelocity Ballistic Models HB-1 and HB-2 at Mach 1.5 to 10; Arnold Engineering Development Center: Tullahoma, TN, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J.D. Summary Report on Aerodynamic Characteristics of Standard Models HB-1 and HB-2; Arnold Engineering Development Center: Tullahoma, TN, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Ye, R.; Jiang, W.; Chen, X. Aerodynamic Test Data of HSCM Calibration Models in Hypersonic Wind Tunnel. Phys. Gases 2021, 6, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Menter, F.R. Two-Equation Eddy-Viscosity Turbulence Models for Engineering Applications. AIAA J. 1994, 32, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinchella, E.; Cauteruccio, A.; Stagnaro, M.; Lanza, L.G. Investigation of the Wind-Induced Airflow Pattern Near the Thies LPM Precipitation Gauge. Sensors 2021, 21, 4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brentner, K.S.; Farassat, F. Analytical Comparison of the Acoustic Analogy and Kirchhoff Formulation for Moving Surfaces. AIAA J. 1998, 36, 1379–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.E.F.; Hawkings, D.L. Sound Generation by Turbulence and Surfaces in Arbitrary Motion. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. Math. Phys. Sci. 1969, 264, 321–342. [Google Scholar]

- Medved, B.; Elfstrom, G. The Yugoslav 1.5M Trisonic Blowdown Wind Tunnel. In Proceedings of the 14th Aerodynamic Testing Conference; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: West Palm Beach, FL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Damljanović, D.; Isaković, J.; Rašuo, B. T-38 Wind-Tunnel Data Quality Assurance Based on Testing of a Standard Model. J. Aircr. 2013, 50, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, Đ.; Damljanović, D. Evaluation of a Force Balance with Semiconductor Strain Gages in Wind Tunnel Tests of the HB-2 Standard Model. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2015, 229, 2272–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Point No. | X | Y | Point No. | X | Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | −1.624 | 0 | S14 | −0.043 | 0.261 |

| S2 | −1.544 | 0 | S15 | −0.002 | 0.064 |

| S3 | −1.464 | 0 | S16 | 0 | 0 |

| S4 | −1.384 | 0 | S17 | −0.043 | −0.261 |

| S5 | −1.304 | 0 | S18 | −0.062 | −0.304 |

| S6 | −1.224 | 0 | S19 | −0.128 | −0.429 |

| S7 | −1.144 | 0 | S20 | −0.160 | −0.446 |

| S8 | −1.064 | 0 | S21 | −0.778 | −0.529 |

| S9 | −1.064 | 0.357 | S22 | −0.690 | −0.529 |

| S10 | −1.064 | −0.357 | S23 | −0.602 | −0.529 |

| S11 | −0.160 | 0.446 | S24 | −0.514 | −0.529 |

| S12 | −0.128 | 0.429 | S25 | −0.426 | −0.529 |

| S13 | −0.0681 | 0.311 | S26 | −0.338 | −0.529 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qian, H.; Wang, W.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, Y. Sensors Layout Optimization Design of Rocket Sled Test System. Sensors 2024, 24, 3641. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113641

Qian H, Wang W, Zhao X, Jiang Y. Sensors Layout Optimization Design of Rocket Sled Test System. Sensors. 2024; 24(11):3641. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113641

Chicago/Turabian StyleQian, Hongjun, Wenjie Wang, Xu Zhao, and Yi Jiang. 2024. "Sensors Layout Optimization Design of Rocket Sled Test System" Sensors 24, no. 11: 3641. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113641