Contrastive Learning with Global and Local Representation for Mixed-Type Wafer Defect Recognition

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- We employ self-supervised contrastive learning for both the classification and segmentation of mixed-type defect patterns. In this way, we can obtain more precise information about the types and locations of different defect patterns.

- (2)

- Our proposed model integrates global and local contrastive learning modules, enabling the learning of both image-level and pixel-level features directly from unlabeled data. This approach provides a robust foundation for downstream classification and segmentation tasks using only a limited amount of labeled data.

- (3)

- Experimental evaluations on the mixed-type WBM defect pattern dataset demonstrate that our framework outperforms existing self-supervised methods.

2. Related Works

2.1. WBM Defect Pattern Recognition

2.2. Self-Supervised Contrastive Learning

3. Methodology

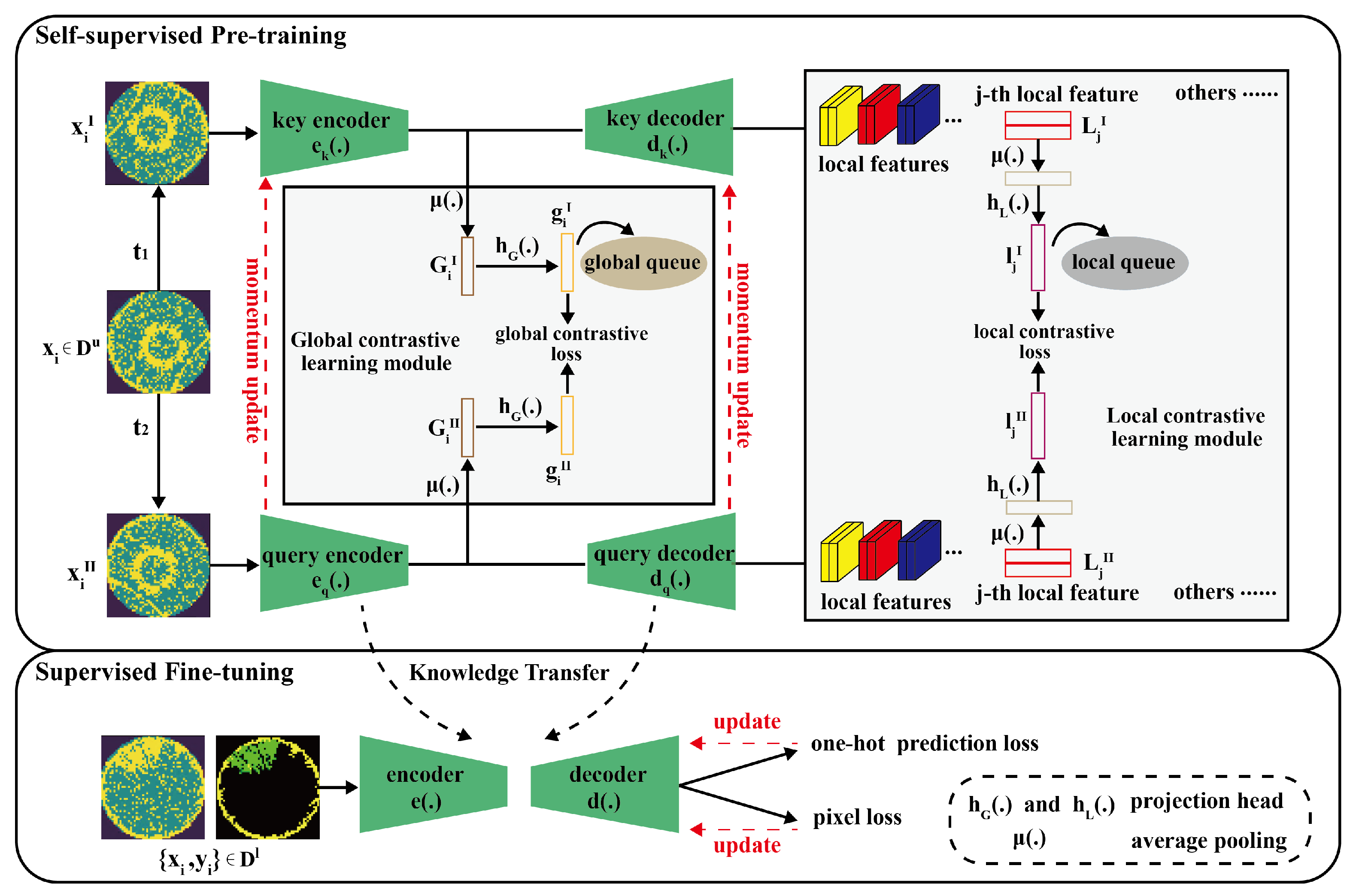

3.1. Overview

3.2. Data Augmentation

3.3. Global Contrastive Learning Module

3.3.1. Global Feature Extraction

3.3.2. Global Contrastive Loss

3.4. Local Contrastive Learning Module

3.4.1. Local Region Selection and Matching

3.4.2. Local Feature Extraction

3.4.3. Local Contrastive Loss

3.5. Network Updating

3.5.1. Self-Supervised Pre-Training

3.5.2. Supervised Fine-Tuning

4. Experimental Results

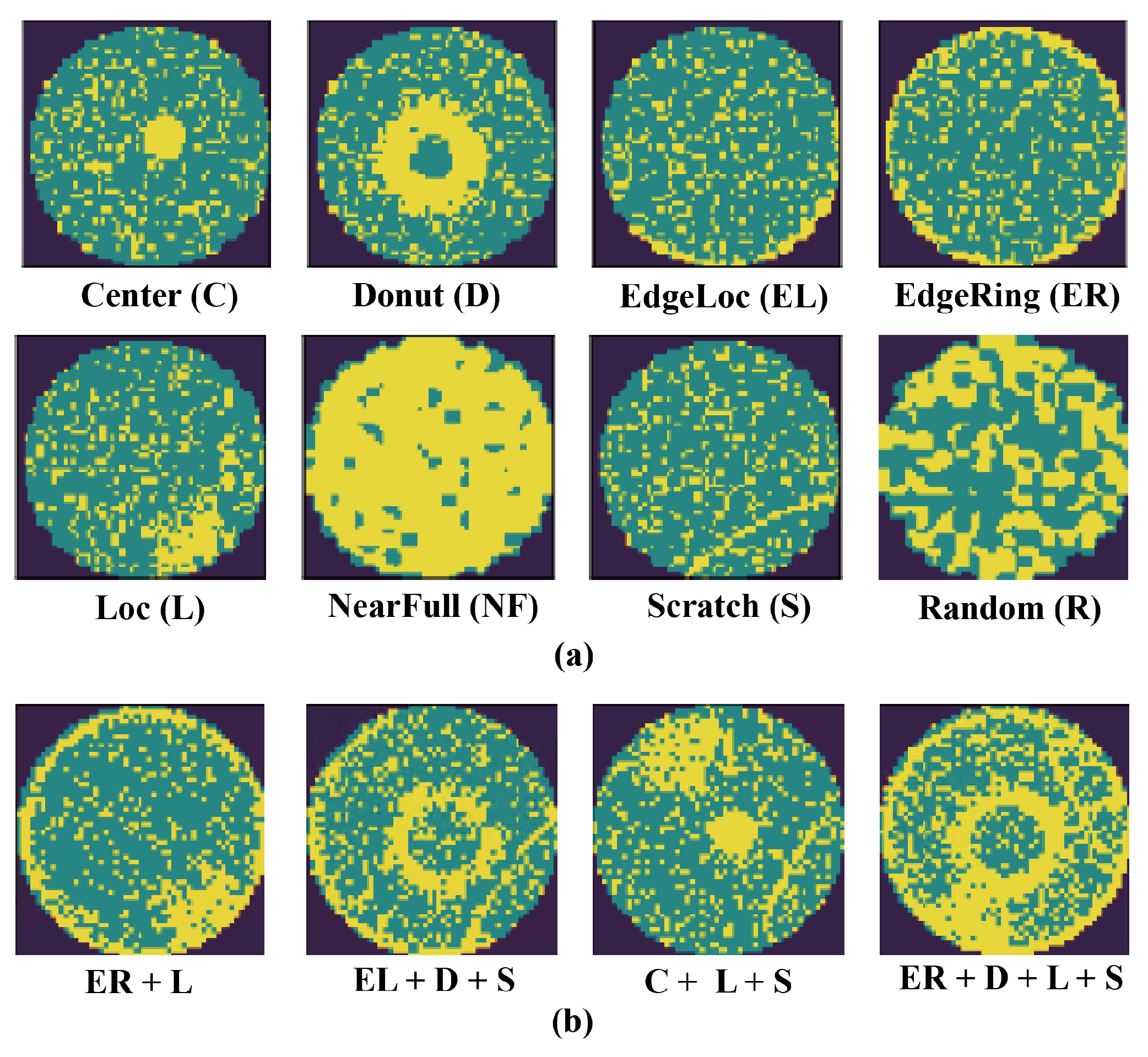

4.1. Data Description

4.2. Model Evaluation

4.3. Performance and Analysis

4.3.1. Implementation Details

4.3.2. Model Performance

4.3.3. Comparison with Other Methods

4.4. Discussion

4.4.1. Effectiveness of the Amount of Self-Supervised Unlabeled Data

4.4.2. Effectiveness of the Amount of Fine-Tuning Labeled Data

4.4.3. Ablation Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shin, E.; Yoo, C.D. Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Semiconductor Wafer Bin Map Classification. Sensors 2023, 23, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, M.-C.; Chen, T.-M. Applying Data Augmentation and Mask R-CNN-Based Instance Segmentation Method for Mixed-Type Wafer Maps Defect Patterns Classification. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2021, 34, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, T.; Kulkarni, D.V. Wafer Map Defect Pattern Classification and Image Retrieval Using Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2018, 31, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, H. Semi-Supervised Multi-Label Learning for Classification of Wafer Bin Maps With Mixed-Type Defect Patterns. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2020, 33, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, C.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, X. Deformable Convolutional Networks for Efficient Mixed-Type Wafer Defect Pattern Recognition. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2020, 33, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.W.; Chien, C.F. An intelligent system for wafer bin map defect diagnosis: An empirical study for semiconductor manufacturing. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2013, 26, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Tang, S.-K. Multi-Scale Contrastive Learning with Hierarchical Knowledge Synergy for Visible-Infrared Person Re-Identification. Sensors 2025, 25, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fan, H.; Girshick, R.; He, K. Improved baselines with momentum contrastive learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.04297. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 12–18 July 2020; pp. 1597–1607. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q. Semantic Segmentation of Traffic Scene Based on DeepLabv3+ and Attention Mechanism. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Networks, Information and Communication Engineering, Guangzhou, China, 10–12 December 2023; pp. 542–547. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, R.; Huang, H.; Zhu, Q.; Tao, C. Global and Local Contrastive Self-Supervised Learning for Semantic Segmentation of HR Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5618014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.I.; Wang, C.H.; Huang, C.L. Monitoring defects in IC fabrication using a Hotelling T/sup 2/ control chart. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2005, 18, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Jeong, Y.S.; Tong, S.H.; Chang, I.K.; Jeong, M.K. Step-Down Spatial Randomness Test for Detecting Abnormalities in DRAM Wafers with Multiple Spatial Maps. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2016, 29, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Kuo, W.; Bensmail, H. Detection and classification of defect patterns on semiconductor wafers. IIE Trans. 2006, 38, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Kuo, W. Spatial defect pattern recognition on semiconductor wafers using model-based clustering and Bayesian inference. Eur. J. Oper. 2008, 190, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Che, N. Wafer Map Defect Pattern Recognition Using Rotation-Invariant Features. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2019, 32, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Kang, S. Semi-supervised rotation-invariant representation learning for wafer map pattern analysis. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 120, 105864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, Y.; Baek, J.G. Mixed Pattern Recognition Methodology on Wafer Maps with Pre-trained Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence, Lisbon, Portugal, 19–21 February 2020; pp. 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tello, G.; Al-Jarrah, O.Y.; Yoo, P.D.; Al-Hammadi, Y.; Muhaidat, S.; Lee, U. Deep-Structured Machine Learning Model for the Recognition of Mixed-Defect Patterns in Semiconductor Fabrication Processes. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2018, 31, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyeong, K.; Kim, H. Classification of Mixed-Type Defect Patterns in Wafer Bin Maps Using Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2018, 31, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, S.; Makwana, D.; Mittal, S.; Mohan, C.K. Wafersegclassnet—A light-weight network for classification and segmentation of semiconductor wafer defects. Comput. Ind. 2022, 142, 103720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Washington, DC, USA, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Sheng, Y.; Piao, M. Semantic Segmentation-Based Wafer Map Mixed-Type Defect Pattern Recognition. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2023, 42, 4065–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, G. Self-Supervised Dam Deformation Anomaly Detection Based on Temporal–Spatial Contrast Learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 5858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, P.; Kern, J.; Raedle, M. Self-Supervised and Zero-Shot Learning in Multi-Modal Raman Light Sheet Microscopy. Sensors 2024, 24, 8143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Yu, S.X.; Lin, D. Unsupervised feature learning via non-parametric instance discrimination. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 3733–3742. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, M.G.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, S.B. SWaCo: Safe Wafer Bin Map Classification With Self-Supervised Contrastive Learning. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2023, 6, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahng, H.; Kim, S.B. Self-supervised representation learning for wafer bin map defect pattern classification. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2020, 34, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; He, C.; Li, P. Semi-supervised Wafer Map Pattern Recognition using Domain-Specific Data Augmentation and Contrastive Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Test Conference, Anaheim, CA, USA, 1–4 November 2021; pp. 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Oord, A.V.D.; Li, Y.; Vinyals, O. Representation learning with contrastive predictive coding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.03748. [Google Scholar]

- Jadon, S. A survey of loss functions for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, Via del Mar, Chile, 3–5 August 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, W.R.; Taber, F.L.; Seitzer, P.W.; Broz, J.J. The leading edge of production wafer probe test technology. In Proceedings of the 2004 International Conferce on Test, Charlotte, NC, USA, 25–29 April 2004; pp. 1168–1195. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Rethinking atrous convolution for semantic image segmentation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.05587. [Google Scholar]

- Noroozi, M.; Favaro, P. Unsupervised learning of visual representations by solving jigsaw puzzles. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 8–16 October 2016; pp. 69–84. [Google Scholar]

| Single-Type | C (C1) | D (C2) | EL (C3) | ER (C4) |

| L (C5) | S (C6) | NF (C7) | R (C8) | |

| Two-Mixed-Type | C + EL (C9) | C + ER (C10) | C + L (C11) | C + S (C12) |

| D + EL (C13) | D + ER (C14) | D + L (C15) | D + S (C16) | |

| EL + L (C17) | EL + S (C18) | ER + L (C19) | ER + S (C20) | |

| L + S (C21) | - | - | - | |

| Three-Mixed-Type | C + EL + L (C22) | C + EL + S (C23) | C + ER + L (C24) | C + ER + S (C25) |

| D + EL + L (C26) | D + EL + S (C27) | D + ER + L (C28) | D + ER + S (C29) | |

| C + L + S (C30) | D + L + S (C31) | EL + L + S (C32) | ER + L + S (C33) | |

| Four-Mixed-Type | C + L + EL + S (C34) | C + L + ER + S (C35) | D + L + EL + S (C36) | D + L + ER + S (C37) |

| Category | C0 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | C7 | C8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segmentation | Pacc | - | 98.69 | 96.40 | 95.95 | 98.02 | 96.90 | 91.49 | 98.74 | 90.11 |

| IoU | - | 96.21 | 94.19 | 93.23 | 95.88 | 96.05 | 89.35 | 97.55 | 88.46 | |

| Classification | Accuracy | 98.75 | 98.67 | 95.83 | 96.89 | 98.41 | 97.04 | 94.54 | 98.72 | 92.32 |

| Precision | 96.66 | 97.24 | 93.46 | 91.89 | 98.74 | 97.30 | 92.07 | 95.41 | 88.74 | |

| Recall | 93.19 | 92.95 | 95.20 | 96.11 | 97.68 | 94.69 | 96.38 | 92.88 | 95.01 | |

| Category | C | D | EL | ER | L | S | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pacc | IoU | Pacc | IoU | Pacc | IoU | Pacc | IoU | Pacc | IoU | Pacc | IoU | |

| C9 | 98.57 | 96.12 | - | - | 95.94 | 93.23 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C10 | 98.66 | 96.19 | - | - | - | - | 97.94 | 95.48 | - | - | - | - |

| C11 | 98.49 | 96.10 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 96.88 | 96.01 | - | - |

| C12 | 98.48 | 96.10 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 91.48 | 89.35 |

| C13 | - | - | 96.23 | 93.89 | 95.66 | 93.10 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C14 | - | - | 96.31 | 94.08 | - | - | 97.91 | 95.47 | - | - | - | - |

| C15 | - | - | 96.20 | 93.88 | - | - | - | - | 96.79 | 95.12 | - | - |

| C16 | - | - | 96.22 | 93.85 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 91.46 | 89.34 |

| C17 | - | - | - | - | 95.21 | 92.16 | - | - | 96.20 | 95.03 | - | - |

| C18 | - | - | - | - | 95.29 | 92.17 | - | - | - | - | 91.34 | 89.19 |

| C19 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 97.82 | 95.40 | 96.77 | 95.13 | - | - |

| C20 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 97.77 | 95.35 | - | - | 91.22 | 89.15 |

| C21 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 96.18 | 94.99 | 90.79 | 88.94 |

| C22 | 98.43 | 96.02 | - | - | 95.32 | 92.20 | - | - | 96.14 | 94.90 | - | - |

| C23 | 98.42 | 96.02 | - | - | 95.32 | 92.21 | - | - | - | - | 90.19 | 88.03 |

| C24 | 98.45 | 96.04 | - | - | - | - | 97.52 | 95.06 | 96.02 | 94.78 | - | - |

| C25 | 98.45 | 96.03 | - | - | - | - | 97.55 | 95.07 | - | - | 90.12 | 87.94 |

| C26 | - | - | 95.18 | 91.98 | 93.40 | 91.03 | - | - | 94.99 | 92.11 | - | - |

| C27 | - | - | 95.15 | 91.90 | 93.39 | 91.03 | - | - | - | - | 90.10 | 89.90 |

| C28 | - | - | 95.20 | 91.92 | - | - | 96.18 | 94.89 | 95.03 | 92.12 | - | - |

| C29 | - | - | 95.18 | 91.97 | - | - | 96.15 | 94.87 | - | - | 90.10 | 87.89 |

| C30 | 98.39 | 95.95 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 94.95 | 92.03 | 90.02 | 87.86 |

| C31 | - | - | 95.11 | 91.86 | - | - | - | - | 94.92 | 92.02 | 90.01 | 87.85 |

| C32 | - | - | - | - | 93.08 | 90.02 | - | - | 94.86 | 91.95 | 89.90 | 87.80 |

| C33 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 96.05 | 94.80 | 94.87 | 91.95 | 89.90 | 87.81 |

| C34 | 97.98 | 95.07 | - | - | 92.11 | 89.20 | - | - | 93.87 | 90.26 | 88.40 | 85.98 |

| C35 | 98.00 | 95.08 | - | - | - | - | 95.11 | 93.57 | 93.89 | 90.27 | 88.41 | 85.98 |

| C36 | - | - | 93.85 | 90.07 | 92.03 | 88.79 | - | - | 93.08 | 89.88 | 88.16 | 85.21 |

| C37 | - | - | 93.90 | 90.10 | - | - | 94.79 | 93.14 | 93.11 | 89.95 | 88.18 | 85.25 |

| Category | Accuracy | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|---|

| C9 | 95.62 | 98.67 | 93.30 |

| C10 | 96.19 | 97.98 | 94.02 |

| C11 | 94.45 | 97.56 | 93.88 |

| C12 | 93.87 | 92.43 | 98.14 |

| C13 | 91.92 | 93.00 | 97.44 |

| C14 | 93.85 | 94.86 | 95.12 |

| C15 | 91.68 | 96.33 | 92.88 |

| C16 | 91.61 | 91.44 | 98.05 |

| C17 | 94.31 | 97.87 | 93.30 |

| C18 | 92.41 | 91.55 | 97.20 |

| C19 | 92.84 | 92.34 | 94.99 |

| C20 | 92.69 | 90.59 | 96.22 |

| C21 | 91.88 | 96.81 | 91.74 |

| C22 | 92.45 | 89.84 | 93.10 |

| C23 | 89.97 | 95.44 | 92.13 |

| C24 | 91.93 | 98.01 | 90.74 |

| C25 | 90.76 | 93.71 | 89.67 |

| C26 | 90.55 | 91.35 | 97.28 |

| C27 | 89.68 | 91.55 | 96.98 |

| C28 | 92.61 | 90.24 | 98.00 |

| C29 | 89.77 | 99.01 | 92.74 |

| C30 | 90.18 | 98.12 | 94.17 |

| C31 | 89.11 | 94.38 | 96.05 |

| C32 | 90.56 | 97.35 | 93.69 |

| C33 | 90.34 | 92.44 | 96.77 |

| C34 | 88.76 | 88.29 | 95.13 |

| C35 | 89.52 | 91.30 | 93.27 |

| C36 | 87.41 | 96.66 | 89.35 |

| C37 | 88.49 | 87.80 | 94.06 |

| Methods | Segmentation (Overall) | Recognition (Overall) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mPacc | mIoU | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | |

| Jigsaw | 83.66 | 76.19 | 80.94 | 78.44 | 81.71 |

| SimCLR | 83.43 | 75.85 | 80.41 | 75.96 | 78.13 |

| MoCo v2 | 84.11 | 78.52 | 82.46 | 80.08 | 83.25 |

| Ours | 95.59 | 92.19 | 93.57 | 94.43 | 94.78 |

| Different Amounts of Pre-Training Unlabeled Data | 1% | 25% | 50% | 75% | 100% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (152) | (3800) | (7600) | (11,400) | (15,200) | ||

| Segmentation results (Overall) | mPacc | 31.12 | 40.55 | 72.64 | 89.33 | 95.59 |

| mIoU | 29.33 | 40.17 | 63.81 | 82.30 | 92.19 | |

| Classification results (Overall) | Accuracy | 27.94 | 38.55 | 70.66 | 86.45 | 93.57 |

| Precision | 28.60 | 41.07 | 70.23 | 85.04 | 94.43 | |

| Recall | 30.41 | 45.02 | 71.38 | 88.10 | 94.78 | |

| Different Amounts of Fine-Tuning Labeled Data | 1% | 5% | 10% | 25% | 50% | 100% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (152) | (760) | (1520) | (3800) | (7600) | (15,200) | ||

| Segmentation results (Overall) | mPacc | 56.32 | 70.92 | 88.25 | 95.54 | 95.72 | 95.80 |

| mIoU | 48.67 | 63.11 | 81.55 | 92.10 | 92.19 | 92.23 | |

| Classification results (Overall) | Accuracy | 57.08 | 71.10 | 87.55 | 93.49 | 93.60 | 93.64 |

| Precision | 58.68 | 75.43 | 89.02 | 94.38 | 94.92 | 95.17 | |

| Recall | 52.87 | 74.16 | 85.39 | 94.77 | 95.06 | 95.33 | |

| Modules | Segmentation (Overall) | Classification (Overall) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | Local | Fine-Tuning | mPacc | mIoU | Accuracy | Precision | Recall |

| √ | √ | √ | 95.59 | 92.19 | 93.57 | 94.43 | 94.78 |

| √ | √ | 75.09 | 71.54 | 72.64 | 75.16 | 71.81 | |

| √ | √ | 84.11 | 78.52 | 82.46 | 80.08 | 83.25 | |

| √ | √ | 86.44 | 80.22 | 84.10 | 80.59 | 85.67 | |

| √ | 52.76 | 45.28 | 50.49 | 49.77 | 55.01 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yin, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R. Contrastive Learning with Global and Local Representation for Mixed-Type Wafer Defect Recognition. Sensors 2025, 25, 1272. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25041272

Yin S, Zhang Y, Wang R. Contrastive Learning with Global and Local Representation for Mixed-Type Wafer Defect Recognition. Sensors. 2025; 25(4):1272. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25041272

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Shantong, Yangkun Zhang, and Rui Wang. 2025. "Contrastive Learning with Global and Local Representation for Mixed-Type Wafer Defect Recognition" Sensors 25, no. 4: 1272. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25041272

APA StyleYin, S., Zhang, Y., & Wang, R. (2025). Contrastive Learning with Global and Local Representation for Mixed-Type Wafer Defect Recognition. Sensors, 25(4), 1272. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25041272