Extension to the Jiles–Atherton Hysteresis Model Using Gaussian Distributed Parameters for Quenched and Tempered Engineering Steels

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Jiles–Atherton Model

3. The Modified Jiles–Atherton Model

3.1. Proposed Model Alterations

3.1.1. Parameter: a

3.1.2. Parameter:

3.1.3. Parameter: c

3.1.4. Parameter: k

3.1.5. Parameter:

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Details of Samples

4.1.1. Steel Chemistries

4.1.2. Heat Treatments

- A: As quenched samples with a fully martensitic microstructure.

- B: Quenched and tempered samples with a hardness in the region of 20 HRC.

- C: Quenched and tempered samples with a hardness in the region of 30 HRC.

- D: Normalised samples with a ferrite-pearlite-bainite microstructure.

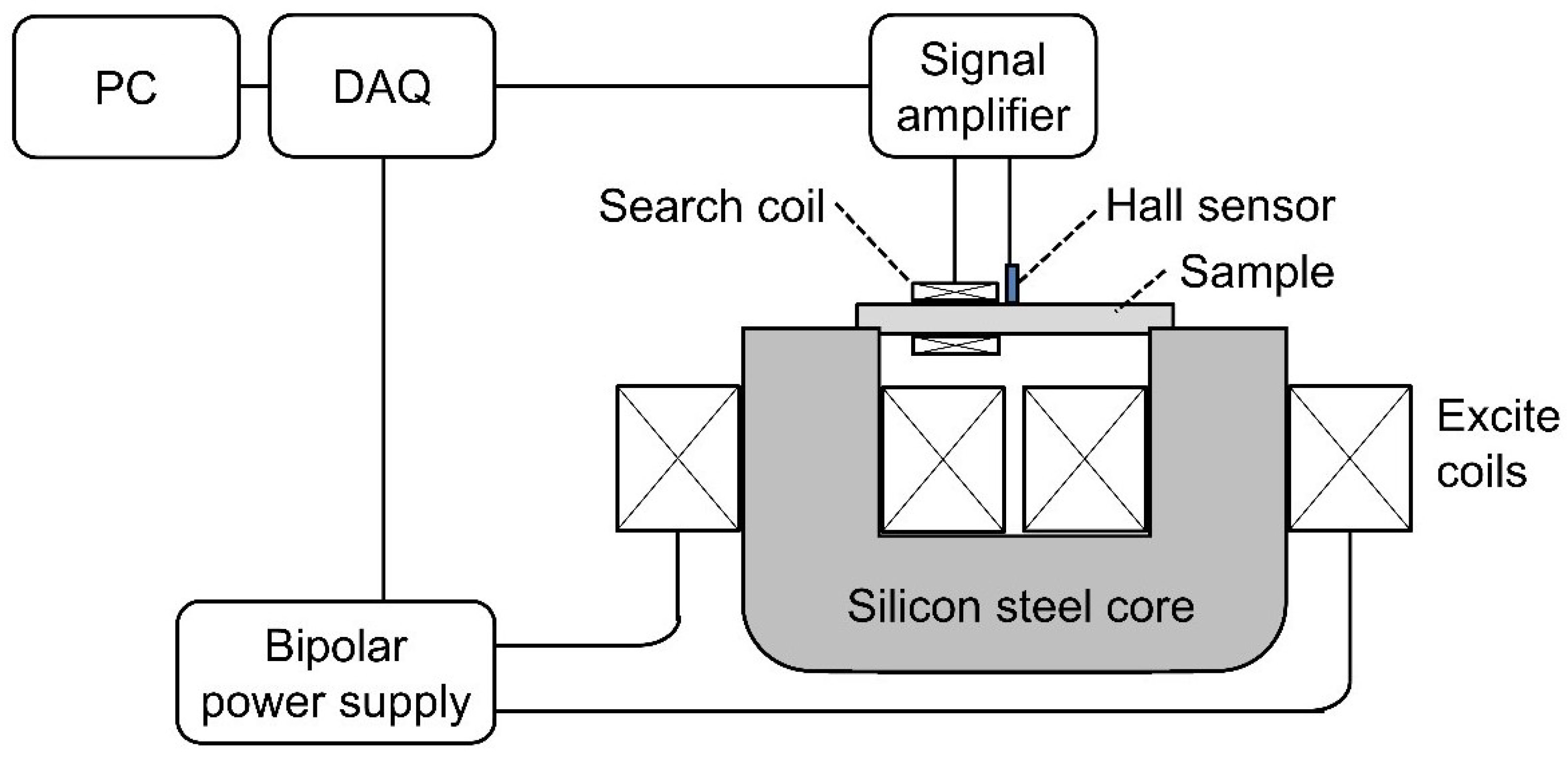

4.2. Experimental Method

4.2.1. Calculating the B-Field

4.2.2. Sample Preparation

4.2.3. Demagnetising the Sample

4.2.4. Major Loop Measurement

4.3. Computational Methods and Parameter Fitting

5. Results and Discussion

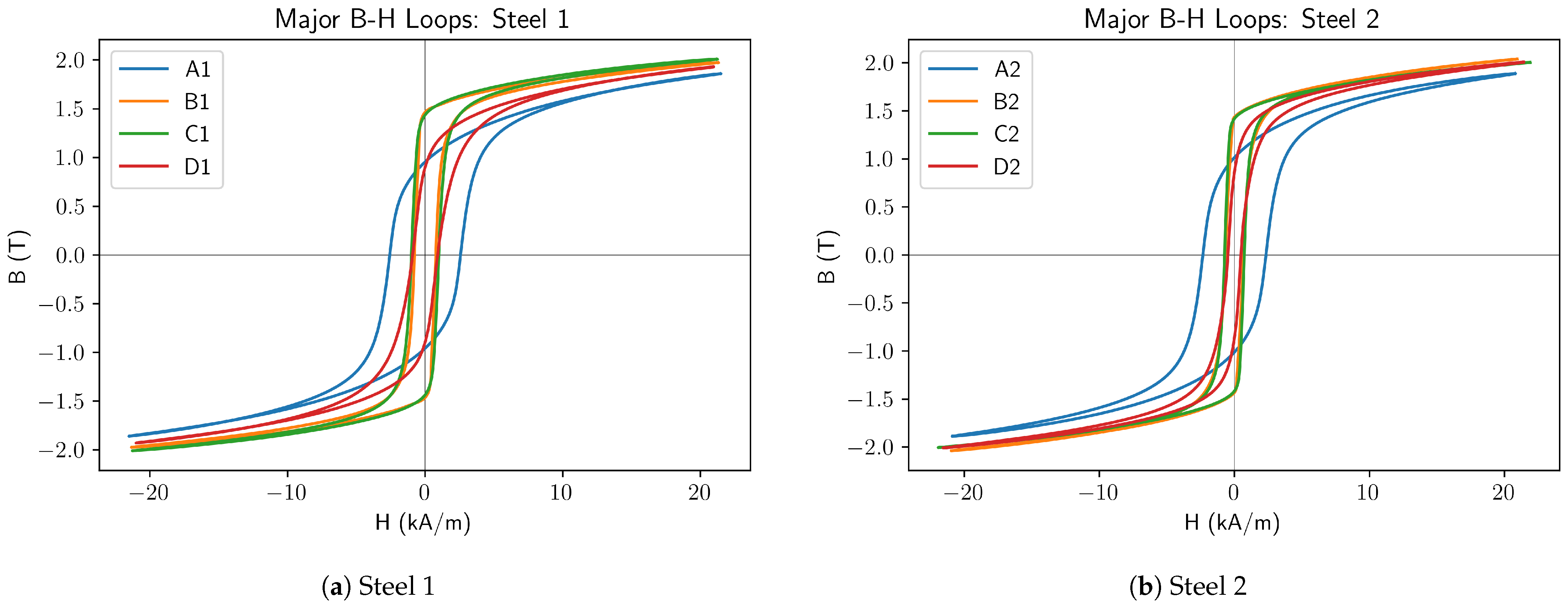

5.1. Experimental Results

5.1.1. As Quenched Samples

5.1.2. Normalised Samples

5.1.3. Quenched and Tempered Samples

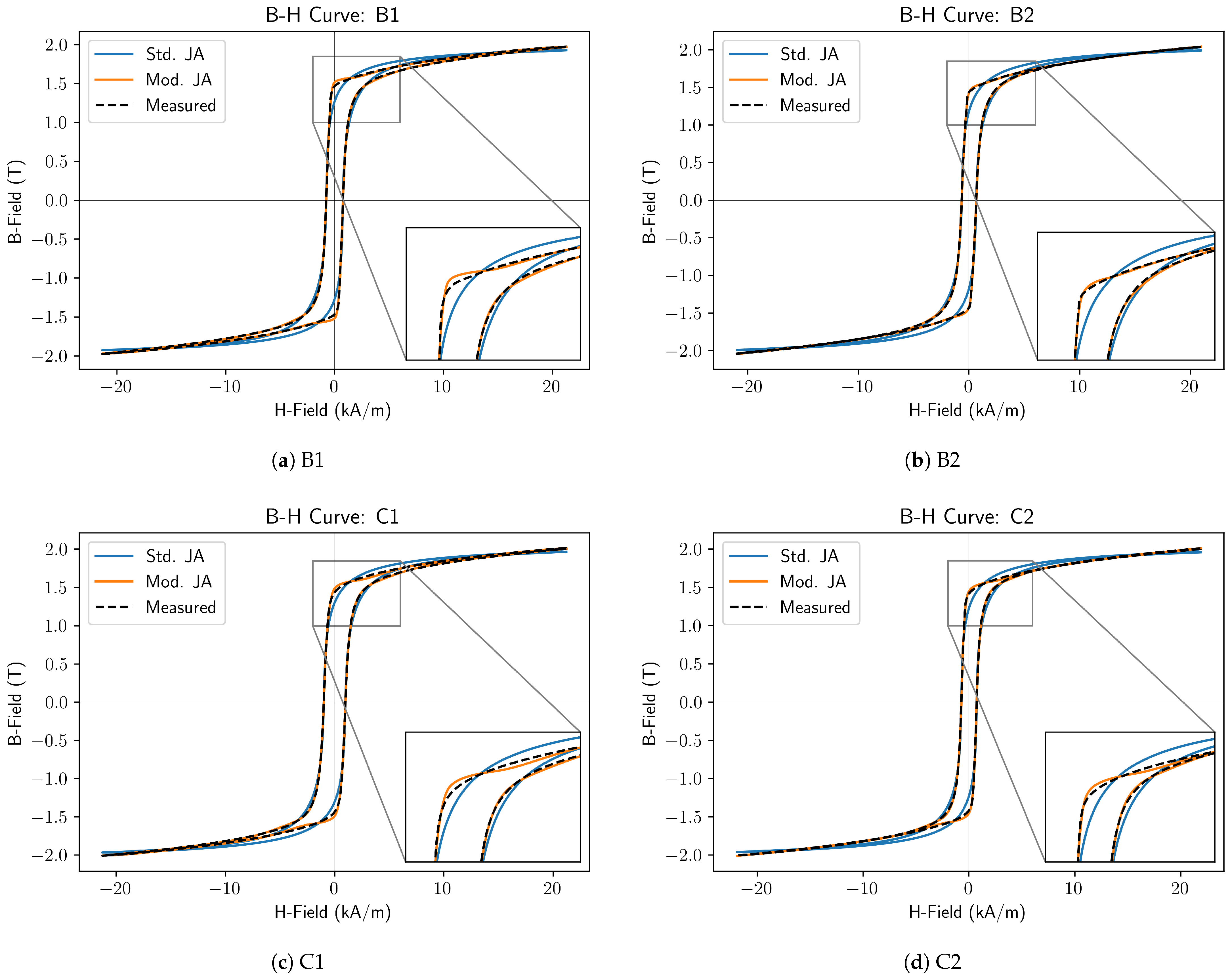

5.2. Curve Fitting

5.3. As Quenched Steels

5.4. Quenched and Tempered Steels

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liorzou, F.; Phelps, B.; Atherton, D.L. Macroscopic models of magnetization. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2000, 36, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mörée, G.; Leijon, M. Review of Hysteresis Models for Magnetic Materials. Energies 2023, 16, 3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mörée, G.; Leijon, M. Review of Play and Preisach Models for Hysteresis in Magnetic Materials. Materials 2023, 16, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiles, D.; Atherton, D. Ferromagnetic hysteresis. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1983, 19, 2183–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiles, D.C.; Atherton, D.L. Theory of ferromagnetic hysteresis (invited). J. Appl. Phys. 1984, 55, 2115–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiles, D.C.; Atherton, D.L. Theory of ferromagnetic hysteresis. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1986, 61, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergqvist, A.J. A simple vector generalization of the Jiles-Atherton model of hysteresis. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1996, 32, 4213–4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COMSOL. COMSOL. Available online: https://www.comsol.com/ (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Altair. Altair. Available online: https://altair.com/ (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Szewczyk, R. Progress in development of Jiles-Atherton model of magnetic hysteresis. Proc. AIP Conf. Proc. Am. Inst. Phys. 2019, 2131, 020045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, G.; Zhang, P.; He, Z.; Li, D.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, Z. Modification and Numerical Method for the Jiles-Atherton Hysteresis Model. Commun. Comput. Phys. 2017, 21, 763–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedrzycki, R.; Szewczyk, R.; Švec, P.; Winiarski, W. Determination of Jiles-Atherton Model Parameters Using Differential Evolution; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 317, pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, R. Computational Problems Connected with Jiles-Atherton Model of Magnetic Hysteresis; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, L.; Gao, J.; Jiles, D.; Welch, D. Modeling of permanent magnets: Interpretation of parameters obtained from the Jiles-Atherton hysteresis model. J. Appl. Phys. 1996, 79, 6470–6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Kim, H.J.; Li, W.; Koh, C.S. Analysis of Magnetizing Process of a New Anisotropic Bonded NdFeB Permanent Magnet Using FEM Combined with Jiles-Atherton Hysteresis Model. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2013, 49, 2221–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Shi, Y.; Jiles, D. Modeling of magnetic properties of heat treated Dy-doped NdFeB particles bonded in isotropic and anisotropic arrangements. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1998, 34, 1291–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Jiles, D.; Branagan, D.; McCallum, R. Dependence of energy dissipation on annealing temperature of melt-spun NdFeB permanent magnet materials. J. Appl. Phys. 1996, 79, 5510–5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brachtendorf, H.; Laur, R. A hysteresis model for hard magnetic core materials. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1997, 33, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annakkage, U.; McLaren, P.; Dirks, E.; Jayasinghe, R.; Parker, A. A current transformer model based on the Jiles-Atherton theory of ferromagnetic hysteresis. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2000, 15, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toman, M.; Stumberger, G.; Dolinar, D. Parameter Identification of the Jiles-Atherton Hysteresis Model Using Differential Evolution. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2008, 44, 1098–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haned, N.; Missous, M. Nano-tesla magnetic field magnetometry using an InGaAs–AlGaAs–GaAs 2DEG Hall sensor. Sensors Actuators Phys. 2003, 102, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiles, D.; Thoelke, J. Theory of ferromagnetic hysteresis: Determination of model parameters from experimental hysteresis loops. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1989, 25, 3928–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiles, D.C.; Thoelke, J.B.; Devine, M.K. Numerical determination of hysteresis parameters for the modeling of magnetic properties using the theory of ferromagnetic hysteresis. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1992, 28, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiles, D. Introduction to Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, 3rd ed.; CRC Press; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lederer, D.; Igarashi, H.; Kost, A.; Honma, T. On the parameter identification and application of the Jiles-Atherton hysteresis model for numerical modelling of measured characteristics. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1999, 35, 1211–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.R.; Ross, J.N.; Brown, A.D. Optimizing the Jiles-Atherton model of hysteresis by a genetic algorithm. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2001, 37, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, J.; Avila, S.; Batistela, N.; Carpes, W.; Sadowski, N.; Kuo-Peng, P.; Bastos, J. Real coded genetic algorithm for Jiles-Atherton model parameters identification. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2004, 40, 888–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, J.; Sadowski, N.; Kuo-Peng, P.; Batistela, N.; Bastos, J. The inverse Jiles-Atherton model parameters identification. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2003, 39, 1397–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kis, P.; Iványi, A. Parameter identification of Jiles–Atherton model with nonlinear least-square method. Phys. Condens. Matter 2004, 343, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwastek, K.; Szczyglowski, J.; Najgebauer, M. A direct search algorithm for estimation of Jiles–Atherton hysteresis model parameters. Mater. Sci. Eng.-Solid-State Mater. Adv. Technol. 2006, 131, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulginei, F.R.; Salvini, A. Softcomputing for the identification of the Jiles–Atherton model parameters. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2005, 41, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghel, A.P.S.; Kulkarni, S.V. Parameter identification of the Jiles―Atherton hysteresis model using a hybrid technique. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2012, 6, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapanese, M. Identification of parameters of the Jiles–Atherton model by neural networks. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 07D355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential Evolution - A Simple and Efficient Heuristic for global Optimization over Continuous Spaces. J. Glob. Optim. 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, K.V.; Storn, R.M.; Lampinen, J.A. Differential Evolution: A Practical Approach to Global Optimization; Natural Computing Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| Sample | Chemistry | Heat Treatment | Average Hardness |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | - | As quenched | 46.5 HRC |

| B1 | Quenched & tempered at °C (30 min) | 19 HRC | |

| C1 | Quenched & tempered at °C (30 min) | 32.3 HRC | |

| D1 | Normalised | 17.5 HRC | |

| A2 | C- | As quenched | 48.32 HRC |

| B2 | Quenched & tempered at °C (12 min) | 18.5 HRC | |

| C2 | Quenched & tempered at °C (12 min) | 29 HRC | |

| D2 | Normalised | 85.5 HRB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Regan, A.; Wilson, J.; Peyton, A.J. Extension to the Jiles–Atherton Hysteresis Model Using Gaussian Distributed Parameters for Quenched and Tempered Engineering Steels. Sensors 2025, 25, 1328. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051328

Regan A, Wilson J, Peyton AJ. Extension to the Jiles–Atherton Hysteresis Model Using Gaussian Distributed Parameters for Quenched and Tempered Engineering Steels. Sensors. 2025; 25(5):1328. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051328

Chicago/Turabian StyleRegan, Alasdair, John Wilson, and Anthony J. Peyton. 2025. "Extension to the Jiles–Atherton Hysteresis Model Using Gaussian Distributed Parameters for Quenched and Tempered Engineering Steels" Sensors 25, no. 5: 1328. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051328

APA StyleRegan, A., Wilson, J., & Peyton, A. J. (2025). Extension to the Jiles–Atherton Hysteresis Model Using Gaussian Distributed Parameters for Quenched and Tempered Engineering Steels. Sensors, 25(5), 1328. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051328