Human-Centered Sensor Technologies for Soft Robotic Grippers: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

- (1)

- Only the peer-reviewed studies that have been published in the English language;

- (2)

- The study must involve soft robotic sensors used in various applications;

- (3)

- Studies that specifically show different kinds of sensors used in soft robotics;

- (4)

- Those scientific papers/articles that were published between 1960 and 2023 (July);

- (5)

- The literature search was restricted to journal papers, conference proceedings, books, reports, and relevant websites;

- (6)

- Newly developed sensors that are being used in commercial aspects but have yet to receive publications;

- (7)

- AI and data fusion in sensor technology that are physically the same sensor, but where data manipulation results in less computational power as it is also included as a sensor.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

- (1)

- There was no precise research population (for example, not specified or overly wide);

- (2)

- Not technically scientific articles, such as editorials or opinions;

- (3)

- Sensors that are not related to soft robotics;

- (4)

- Sensors that are too big and cannot be used as biosensors.

3. Soft Robotics and the Importance of Sensing Systems

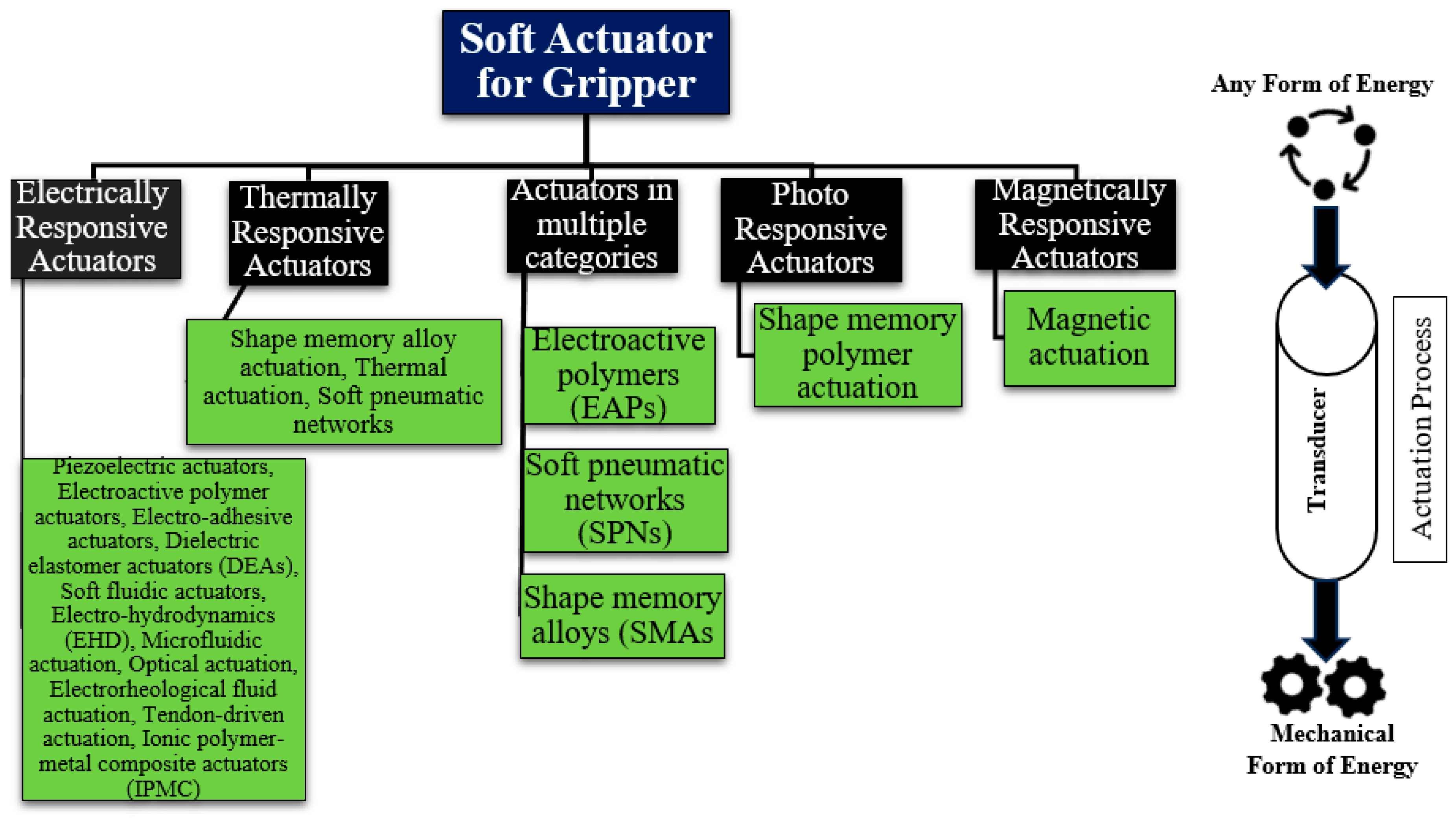

4. Degree-of-Freedom Actuation Systems in Soft Robotics

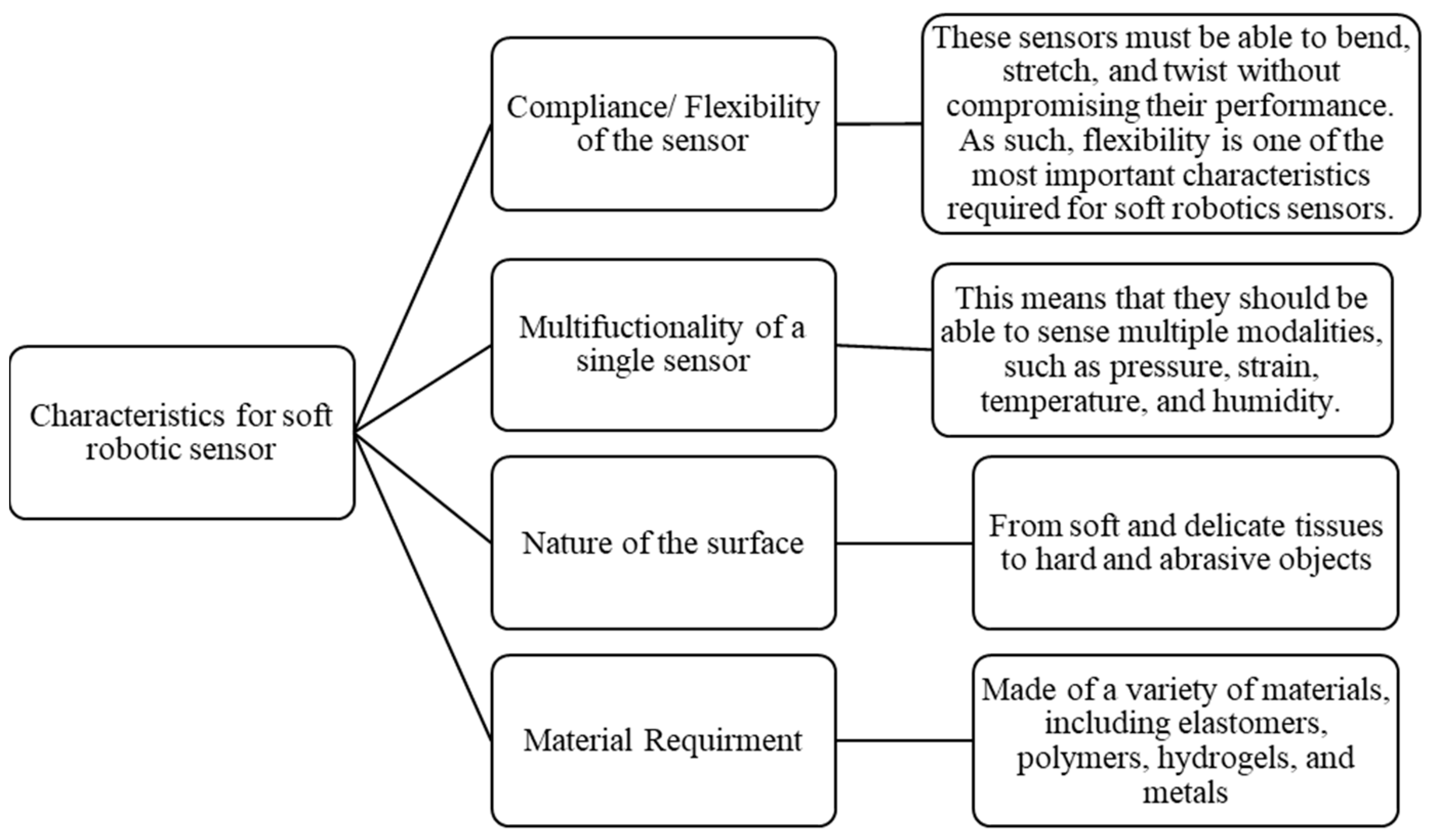

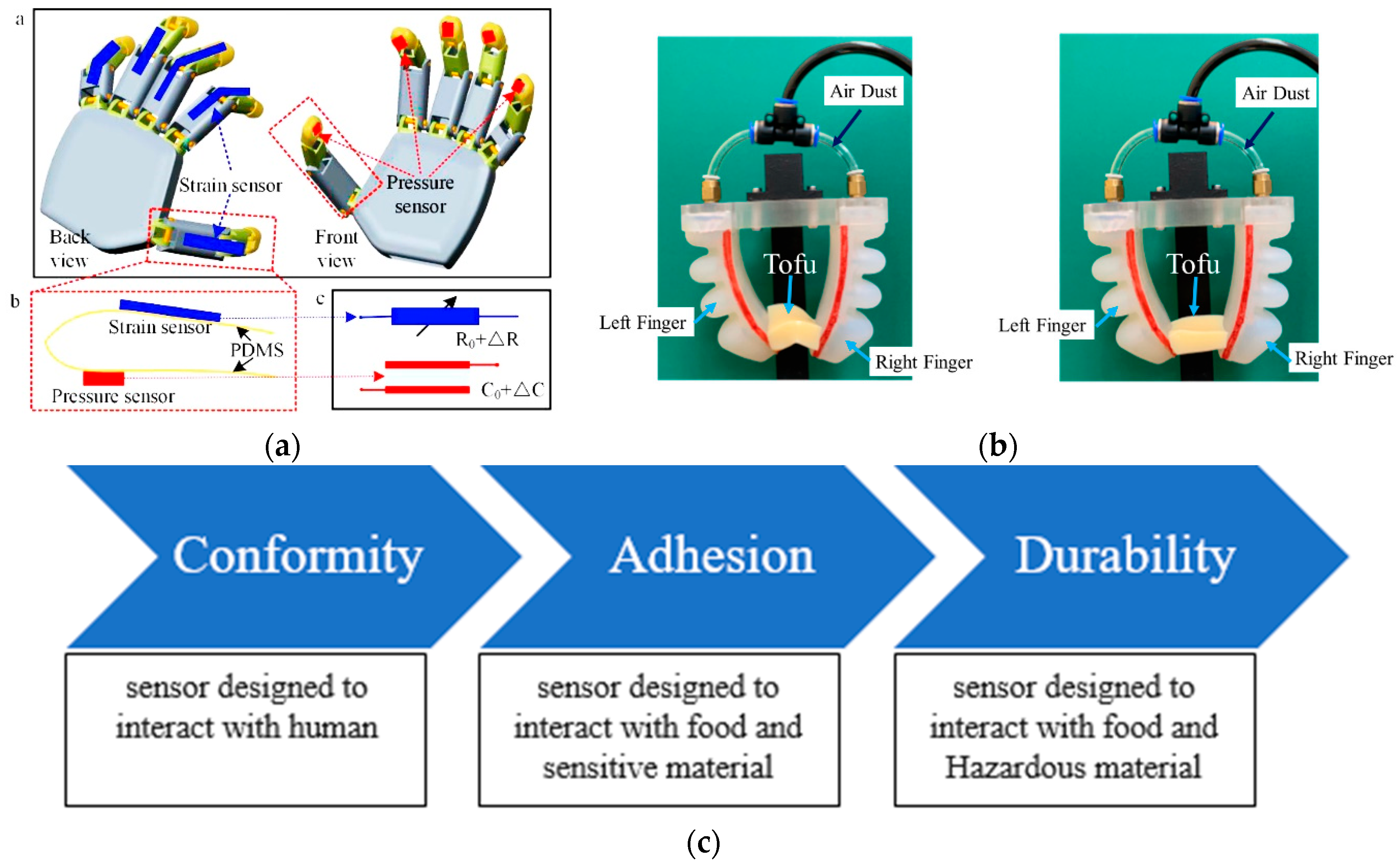

5. Important Characteristics Required for Soft Robotic Sensors

5.1. Compliance/Flexibility

5.2. Nature of the Soft Robotic Sensor Surface

5.3. Material Requirements in the Construction of Soft Sensors

5.4. Multifunctional Sensor

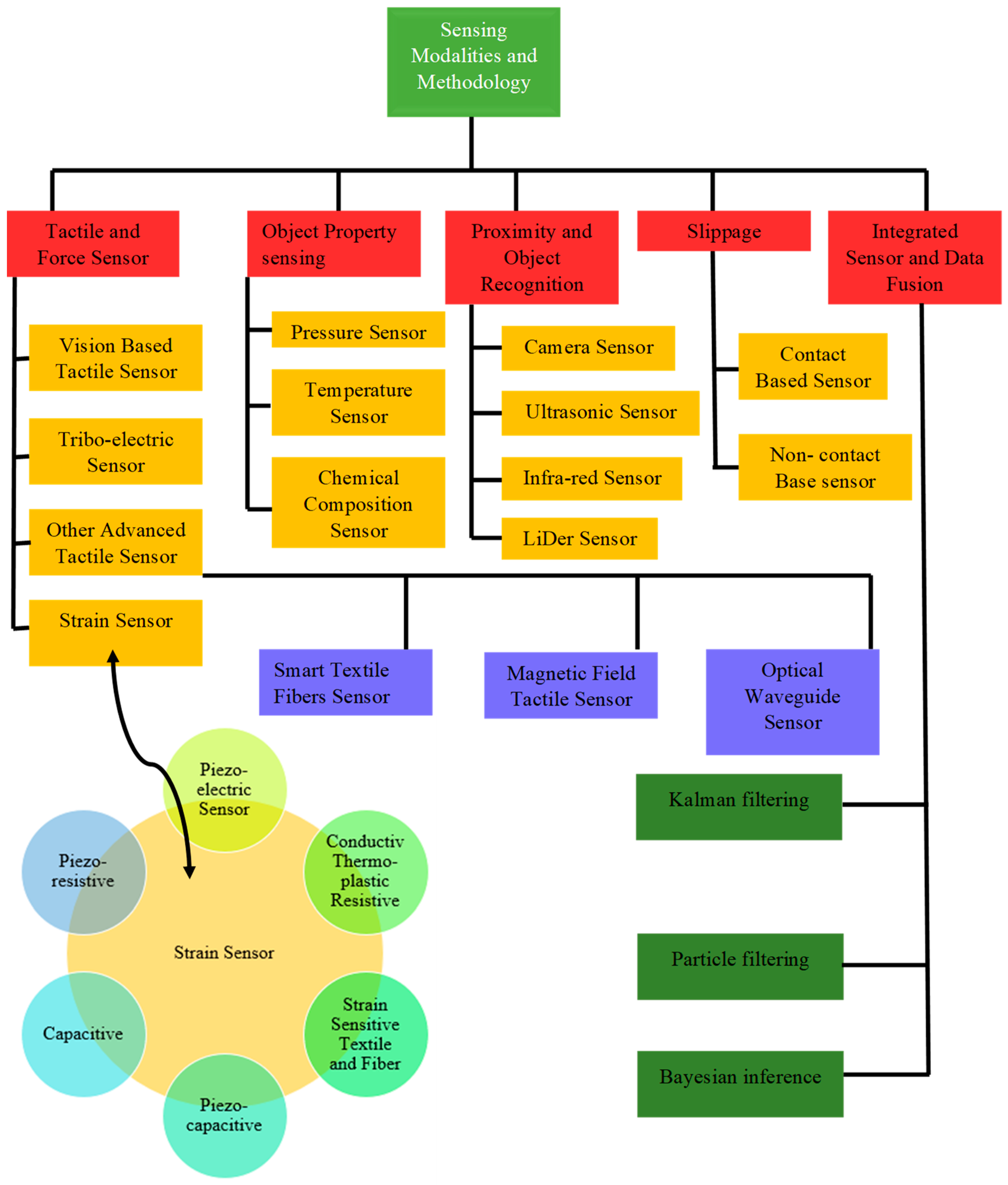

6. Types of Sensors for Soft Robotic Grippers

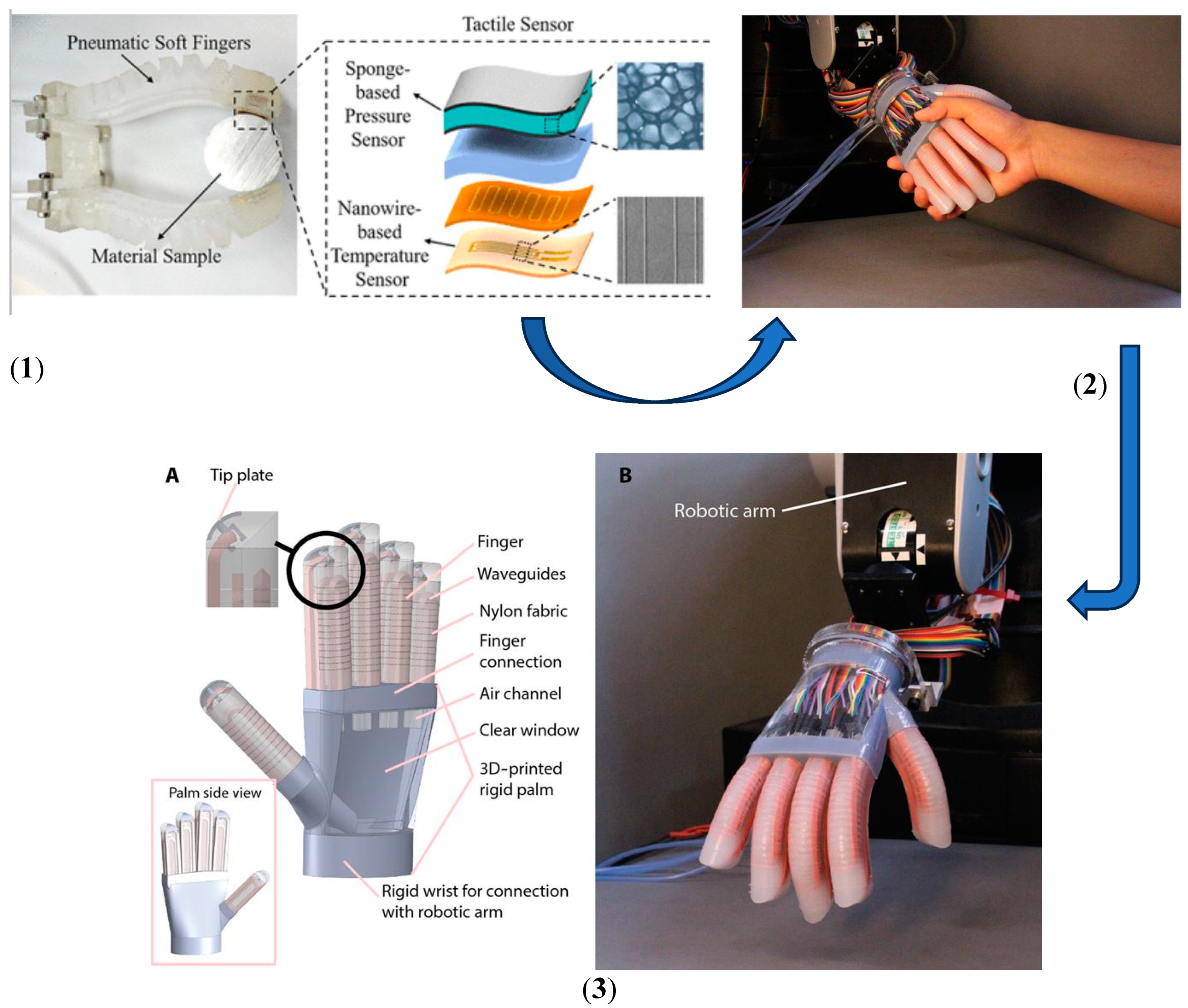

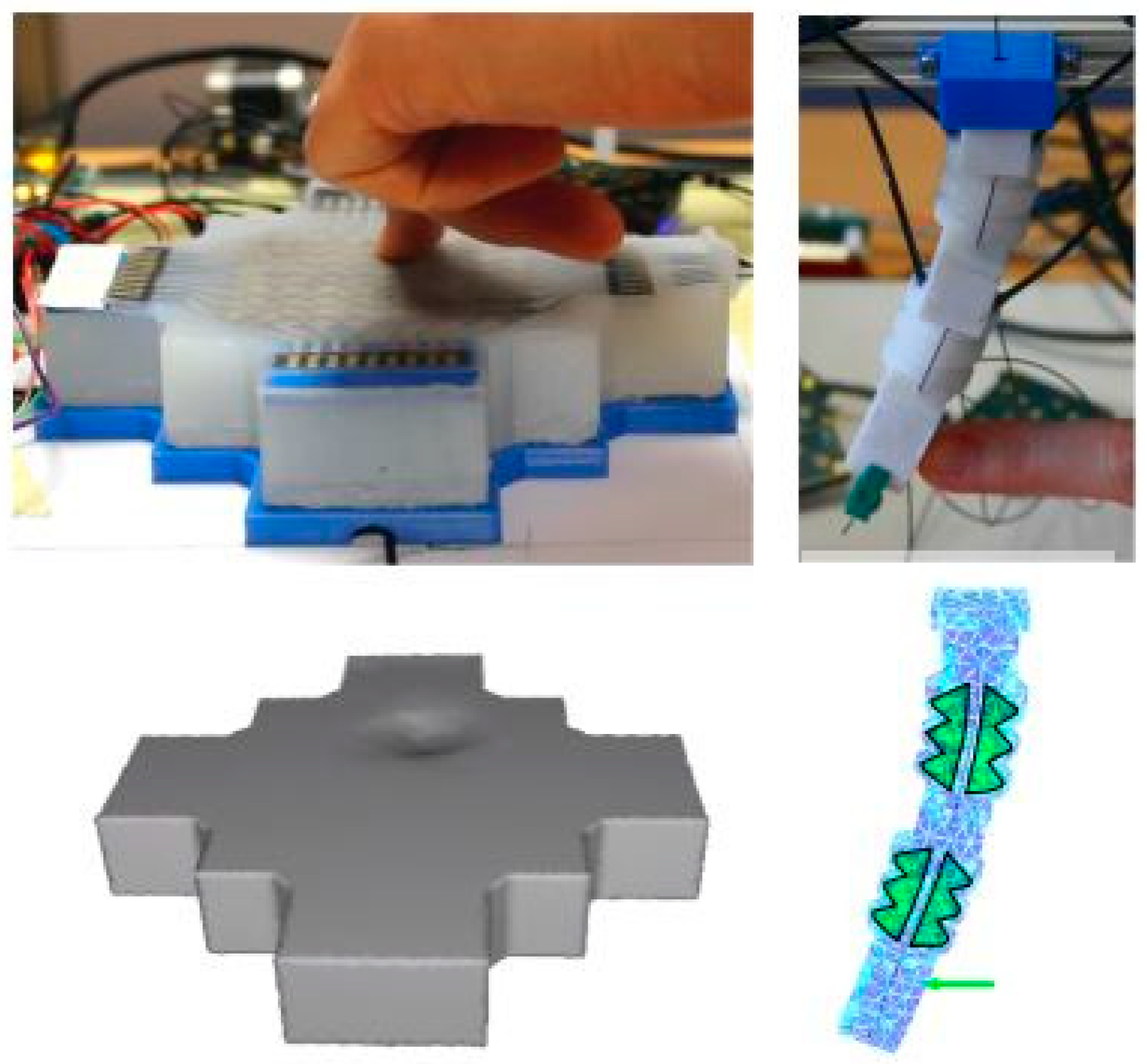

6.1. Tactile and Force Sensing

| Type of Sensor | Working Principle | Measurement | Advantage | Limitation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistive Ionic | Change in electrical resistance due to the movement of ions in a liquid or gel. | Liquid or gel level, concentration, and density. | Low cost and simple to use. | Not very accurate and can be affected by temperature. | [64] |

| Piezoelectric | Generation of an electrical charge when the sensor is subjected to mechanical stress. | Force, pressure, and acceleration. | High sensitivity and accuracy. | Expensive and fragile. | [65] |

| Piezoresistive | Change in electrical resistance due to mechanical stress. | Force, pressure, and acceleration. | Low cost and durable. | Not as sensitive as piezoelectric sensors. | [66] |

| Piezo-capacitive Strain | Change in capacitance due to mechanical stress. | Strain, pressure, and acceleration. | High sensitivity and accuracy. | Expensive and fragile. | [67] |

| Flexible Electronics | Use of flexible materials to create sensors. | A variety of measurements, including strain, pressure, temperature, and chemical concentration. | Lightweight and conformable to curved surfaces. | Not as durable as traditional sensors. | [68] |

| Capacitive Strain | Change in capacitance due to the change in distance between two electrodes. | Strain, pressure, and displacement. | High sensitivity and accuracy. | Can be affected by environmental factors such as moisture and dust. | [69] |

| Conductive Thermoplastic Resistive Strain | Change in electrical resistance due to the change in temperature of a conductive thermoplastic material. | Strain, temperature, and pressure. | Low cost and durable. | Not as sensitive as other strain sensors. | [70] |

| Optical Sensing | Use of light to measure various physical and chemical properties. | A variety of measurements, including strain, pressure, temperature, and chemical concentration. | Non-contact and can be used in hazardous environments. | Can be expensive and complex. | [71] |

| Strain-Sensitive Textiles and Fibers | Use of textiles and fibers to create strain sensors. | Strain, pressure, and movement. | Lightweight and conformable to curved surfaces. | Not as durable as traditional sensors. | [72] |

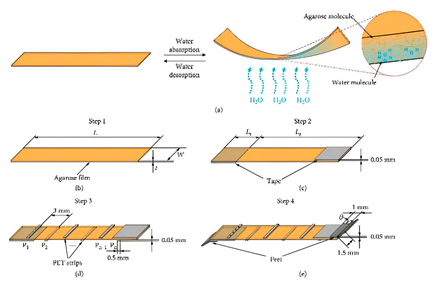

6.2. Object Property Sensing

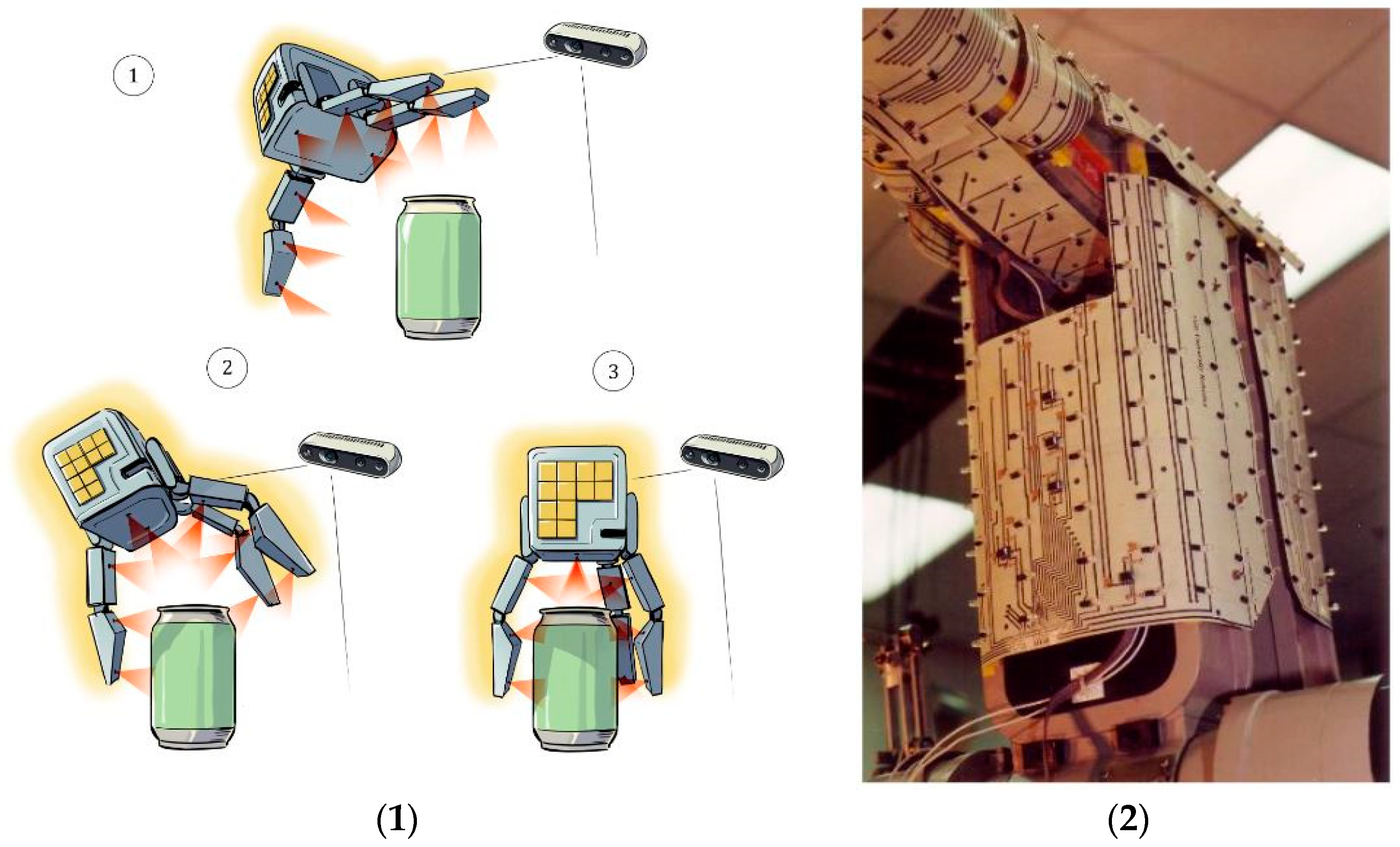

6.3. Proximity and Object Recognition Sensors

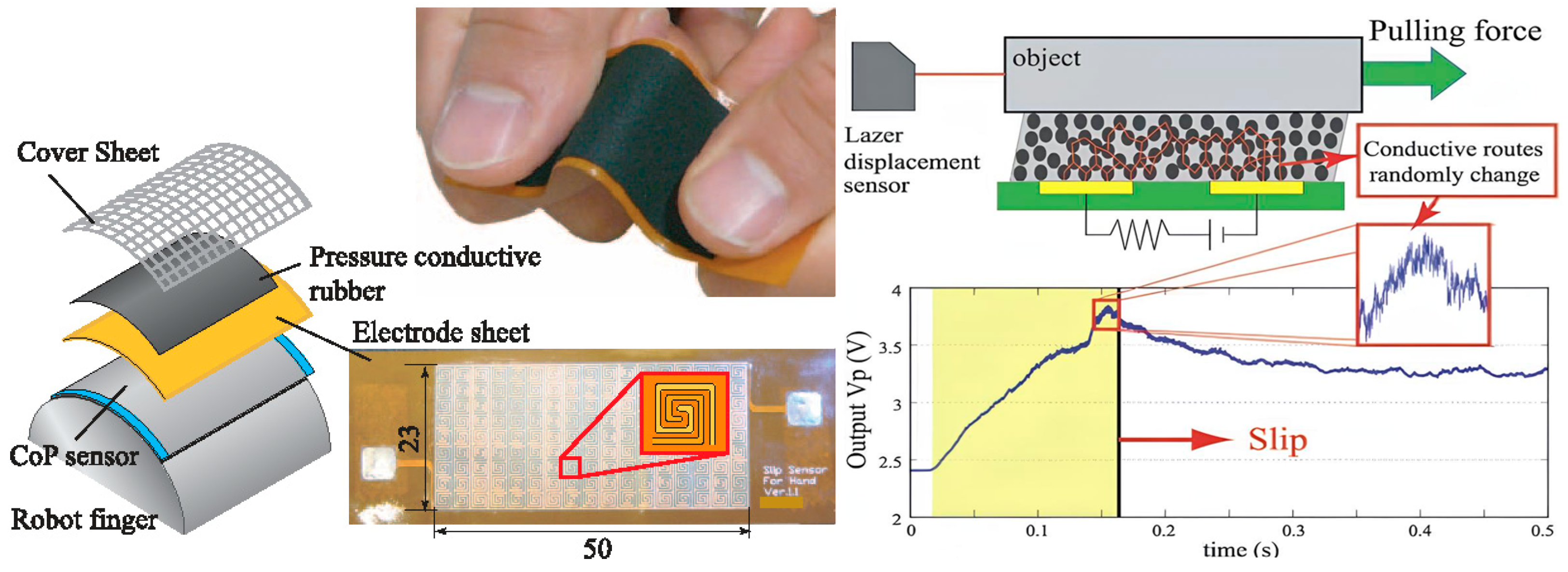

6.4. Slippage Sensor

6.5. Sensor Integration and Data Fusion

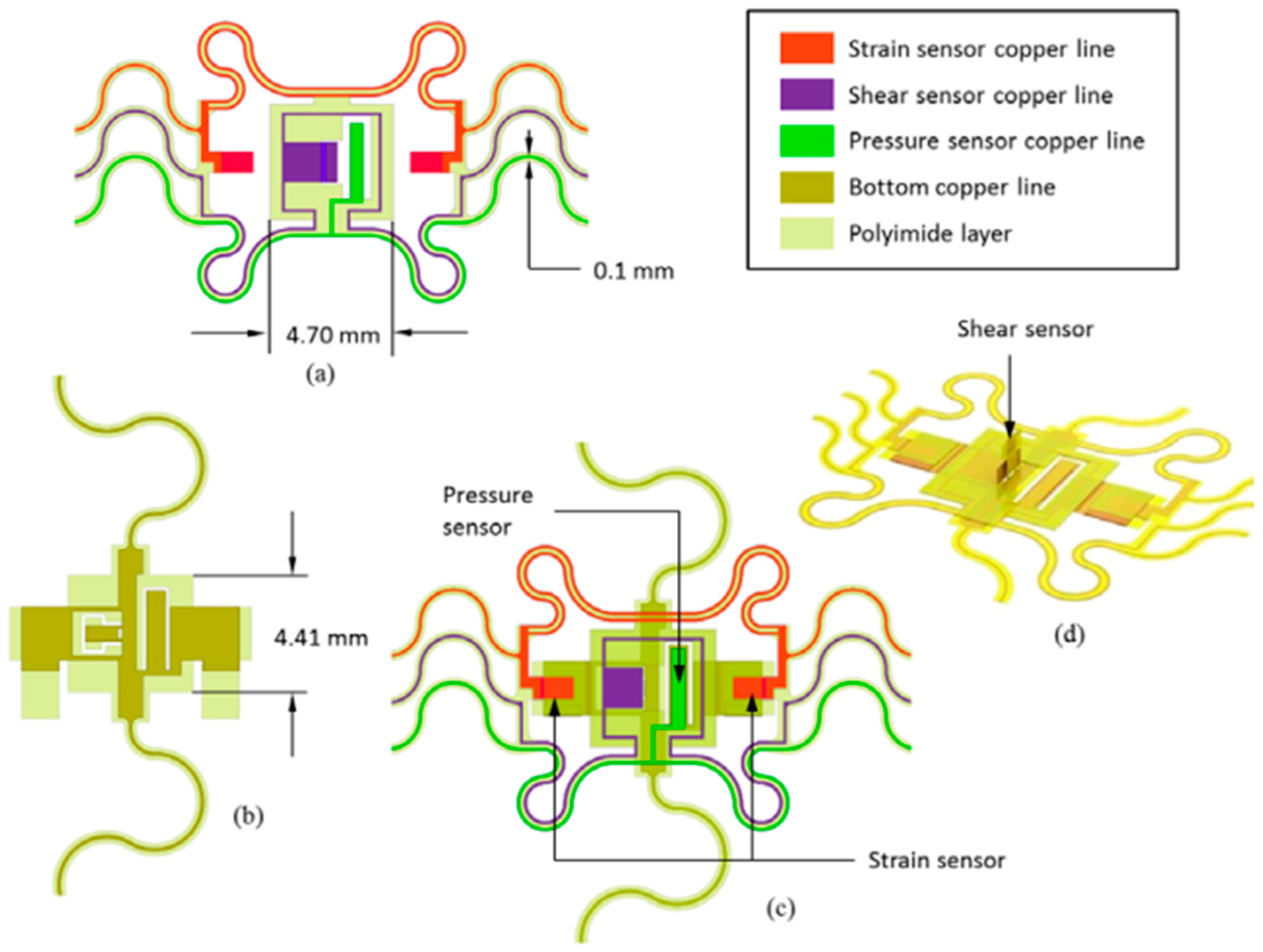

6.6. The Significance of Multimodal Sensors in Soft Robotics

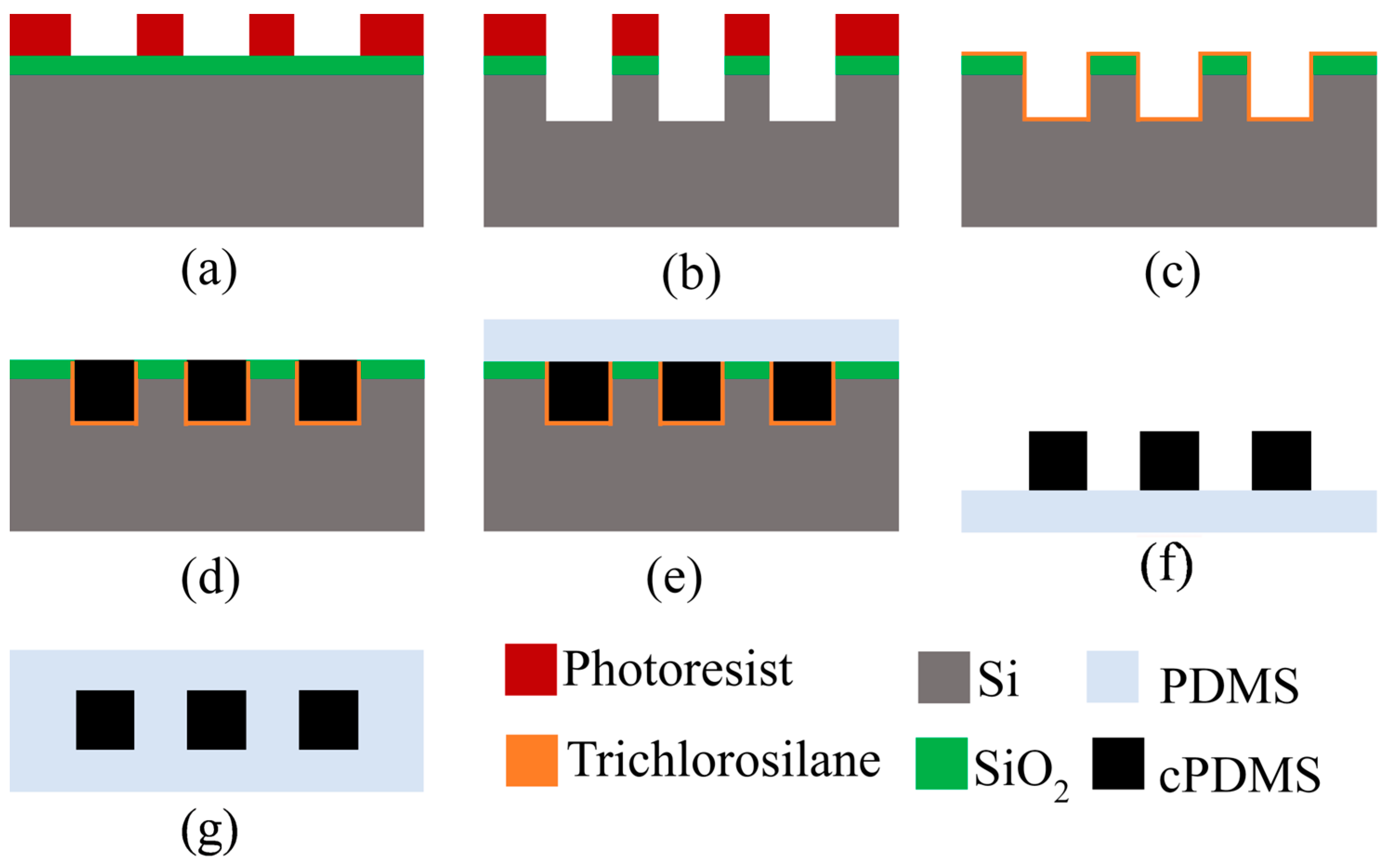

6.7. Fabrication of Soft Sensors in Microscale

7. Sensor Selection Process Using All of the Parameters

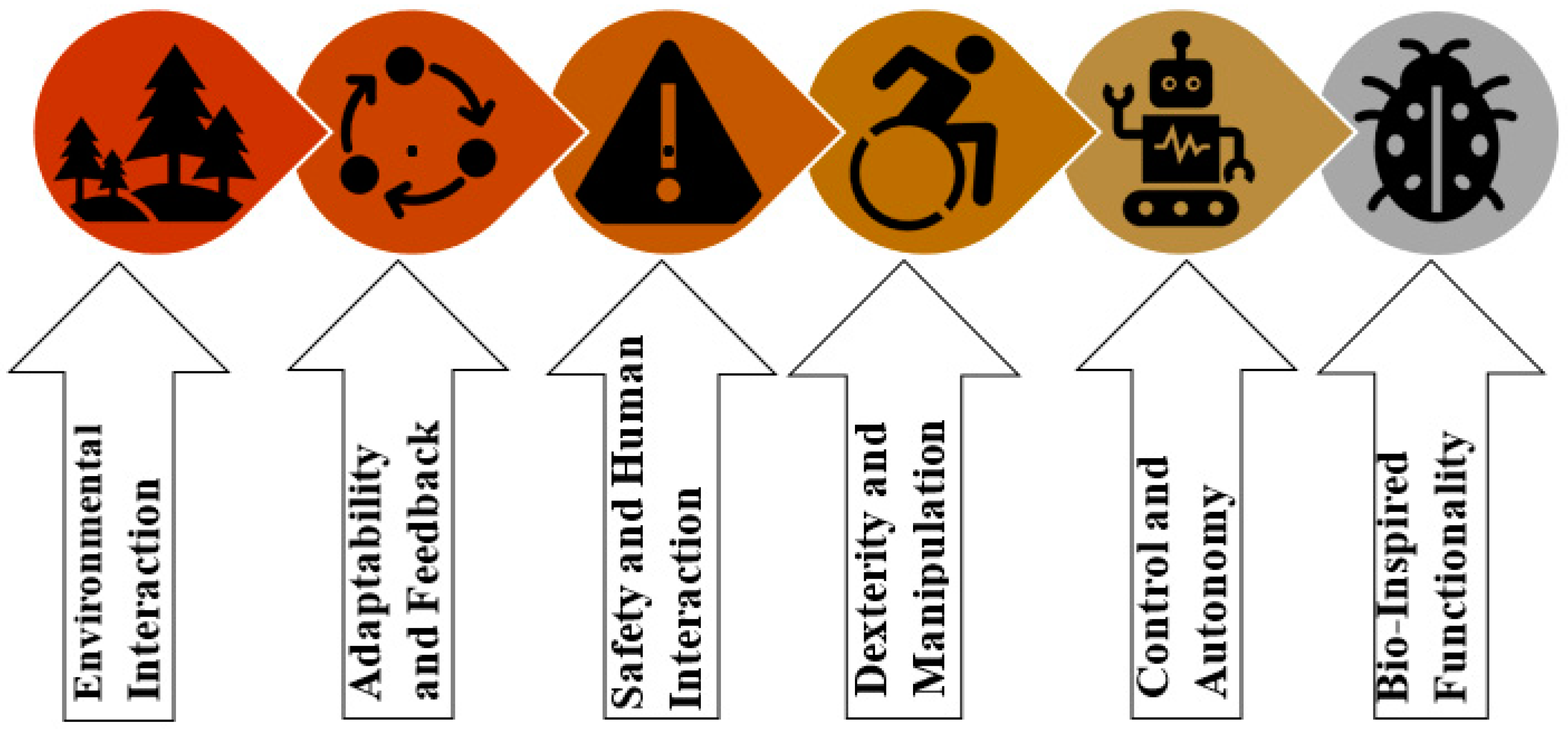

8. Conclusions

- ○

- The parameters considered in the selection of soft robotic sensors have been reported, which are environmental condition, adaptability and feedback, safety and human interaction, dexterity and manipulation, control and autonomy, and bio-inspired functionality;

- ○

- Soft robotic sensors require distinctive features that go beyond traditional metrics such as accuracy, precision, and sensitivity. The key characteristics include compliance, flexibility, multifunctionality, sensor nature, surface properties, and material requirements;

- ○

- The categorization of sensor types for soft robotic grippers provided insights into tactile and force sensing, object property sensing, proximity sensing, and the integration of multimodal sensors. These sensor modalities facilitate soft grippers to interact intelligently with their environment, facilitating tasks ranging from delicate interactions to complex object recognition;

- ○

- Acknowledging tactile sensing as one of the most important tactile sensors has been explored, including piezoelectric, piezoresistive, resistive ionic, piezocapacitive strain, capacitive strain, and optical sensing;

- ○

- Multimodal sensors play a fundamental role in the field of soft robotics by facilitating the acquisition of diverse information pertaining to the surrounding environment and various objects;

- ○

- The sensor selection process outlined in this study serves as a practical guide for engineers and researchers, emphasizing the importance of considering various factors such as application-specific requirements and fabrication methods. We aim to contribute to the advancement of this rapidly evolving field by proposing a comprehensive model for sensor selection in soft robotic applications.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Craddock, M.; Augustine, E.; Konerman, S.; Shin, M. Biorobotics: An Overview of Recent Innovations in Artificial Muscles. Actuators 2022, 11, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannsfeld, S.C.B.; Tee, B.C.-K.; Stoltenberg, R.M.; Chen, C.V.H.-H.; Barman, S.; Muir, B.V.O.; Sokolov, A.N.; Reese, C.; Bao, Z. Highly sensitive flexible pressure sensors with microstructured rubber dielectric layers. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Lin, L.; Wang, Z.L. Nanoscale Triboelectric-Effect-Enabled Energy Conversion for Sustainably Powering Portable Electronics. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 6339–6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, E.; Rodenberg, N.; Amend, J.; Mozeika, A.; Steltz, E.; Zakin, M.R.; Lipson, H.; Jaeger, H.M. Universal robotic gripper based on the jamming of granular material. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 18809–18814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, R.F.; Ilievski, F.; Choi, W.; Morin, S.A.; Stokes, A.A.; Mazzeo, A.D.; Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Whitesides, G.M. Multigait soft robot. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20400–20403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wen, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, D. Flexible piezoelectric nanogenerator made of poly (vinylidenefluoride-co-trifluoroethylene) (PVDF-TrFE) thin film. Nano Energy 2014, 7, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keplinger, C.; Sun, J.-Y.; Foo, C.C.; Rothemund, P.; Whitesides, G.; Suo, Z. Stretchable, Transparent, Ionic Conductors. Science 2013, 341, 984–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, D.; Tolley, M.T. Design, fabrication and control of soft robots. Nature 2015, 521, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Lyu, L.; Xu, Y.; Liang, H.; Zhang, X.; Ding, H.; Wu, Z. Intelligent Soft Surgical Robots for Next-Generation Minimally Invasive Surgery. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 3, 2100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.W.; Li, S.; Shepherd, R. Optoelectronically innervated soft prosthetic hand via stretchable optical waveguides. Sci. Robot. 2016, 1, eaai7529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Chen, X.; Song, C.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z. Customizable Three-Dimensional-Printed Origami Soft Robotic Joint With Effective Behavior Shaping for Safe Interactions. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2019, 35, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Yuk, H.; Lin, S.; Jian, N.; Qu, K.; Xu, J.; Zhao, X. Pure PEDOT:PSS hydrogels. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Stalin, S.; Zhao, C.-Z.; Archer, L.A. Designing solid-state electrolytes for safe, energy-dense batteries. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Chen, F.; Zhu, X.; Yong, K.-T.; Gu, G. Stimuli-responsive functional materials for soft robotics. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 8972–8991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Zou, K.; Yi, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z. Underwater Crawling Robot with Hydraulic Soft Actuators. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 688697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, A.; Diethelm, P.; Wagner, M.; Spolenak, R.; Clemens, F.; Georgopoulou, A.; Diethelm, P.; Wagner, M.; Spolenak, R.; Clemens, F. Soft Self-Regulating Heating Elements for Thermoplastic Elastomer-Based Electronic Skin Applications. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 11, e828–e838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.; Zhang, N.; Chen, C.; Xu, H.; Zhu, X. Soft Robotics Enables Neuroprosthetic Hand Design. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 9661–9672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Ma, J.; Sun, Q.; Liu, H. Ionic Liquid-Optoelectronics-Based Multimodal Soft Sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 14809–14818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Totaro, M.; Beccai, L. Toward Perceptive Soft Robots: Progress and Challenges. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1800541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alici, G. Softer is Harder: What Differentiates Soft Robotics from Hard Robotics? MRS Adv. 2018, 3, 1557–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paternò, L.; Lorenzon, L. Soft robotics in wearable and implantable medical applications: Translational challenges and future outlooks. Front. Robot. AI 2023, 10, 1075634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhary, G.; Gazzola, M.; Krishnan, G.; Soman, C.; Lovell, S. Soft Robotics as an Enabling Technology for Agroforestry Practice and Research. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, B.; Shah, D.S.; Li, J.; Thuruthel, T.G.; Park, Y.; Iida, F.; Bao, Z.; Kramer-Bottiglio, R.; Tolley, M. Electronic skins and machine learning for intelligent soft robots. Sci. Robot. 2020, 5, eaaz9239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, V.; Zöller, G.; Brock, O. Passive and active acoustic sensing for soft pneumatic actuators. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2023, 42, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Xie, M.; Zhang, X.; Sun, X.; Zhou, C.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Duan, X. Multifunctional Soft Robotic Finger Based on a Nanoscale Flexible Temperature–Pressure Tactile Sensor for Material Recognition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 55756–55765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Ko, U.H.; Zhou, Y.; Hoque, J.; Arya, G.; Varghese, S. Microengineered Materials with Self-Healing Features for Soft Robotics. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 3, 2100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashuri, T.; Armani, A.; Jalilzadeh Hamidi, R.; Reasnor, T.; Ahmadi, S.; Iqbal, K. Biomedical soft robots: Current status and perspective. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2020, 10, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondoyanni, M.; Loukatos, D.; Maraveas, C.; Drosos, C.; Arvanitis, K.G. Bio-Inspired Robots and Structures toward Fostering the Modernization of Agriculture. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, F. An intrinsically embedded pressure-temperature dual-mode soft sensor towards soft robotics. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2021, 332, 113084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.; Yoon, C. Advances in Stimuli-Responsive Soft Robots with Integrated Hybrid Materials. Actuators 2020, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wu, W. A review: Machine learning for strain sensor-integrated soft robots. Front. Electron. Mater. 2022, 2, 1000781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumet, B.; Bell, M.D.; Sanchez, V.; Preston, D.J. A Data-Driven Review of Soft Robotics. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4, 2100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintake, J.; Cacucciolo, V.; Floreano, D.; Shea, H. Soft Robotic Grippers. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1707035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafer, T. Design Considerations of Anthropomorphic Exoskeleton. Int. J. Sci. Res. (IJSR) 2020, 9, 806–814. [Google Scholar]

- Cianchetti, M.; Laschi, C.; Menciassi, A.; Dario, P. Biomedical applications of soft robotics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polygerinos, P.; Wang, Z.; Galloway, K.C.; Wood, R.J.; Walsh, C.J. Soft robotic glove for combined assistance and at-home rehabilitation. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2015, 73, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ze, Q.; Kuang, X.; Wu, S.; Wong, J.; Montgomery, S.M.; Zhang, R.; Kovitz, J.M.; Yang, F.; Qi, H.J.; Zhao, R. Magnetic Shape Memory Polymers with Integrated Multifunctional Shape Manipulations. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.13171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosadegh, B.; Polygerinos, P.; Keplinger, C.; Wennstedt, S.W.; Shepherd, R.; Gupta, U.; Shim, J.; Bertoldi, K.; Walsh, C.; Whitesides, G. Pneumatic Networks for Soft Robotics that Actuate Rapidly. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 2163–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagoli, A.; Chapelle, F.; Corrales-Ramon, J.-A.; Mezouar, Y.; Lapusta, Y. Review of soft fluidic actuators: Classification and materials modeling analysis. Smart Mater. Struct. 2021, 31, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, Z.; Tan, J.; Peng, J.; Song, C.; Asada, H.H.; Wang, Z. Otariidae-Inspired Soft-Robotic Supernumerary Flippers by Fabric Kirigami and Origami. IEEE-ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2021, 26, 2747–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.-F.; Liu, X.-J.; Dong, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, H. Enhancing the Universality of a Pneumatic Gripper via Continuously Adjustable Initial Grasp Postures. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 37, 1604–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, C.; Su, J.; Tan, J.M.R.; He, K.; Chen, X.; Magdassi, S. Sensing in Soft Robotics. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 15277–15307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghadasi, K.; Mohd Isa, M.S.; Ariffin, M.A.; Mohd Jamil, M.Z.; Raja, S.; Wu, B.; Yamani, M.; Bin Muhamad, M.R.; Yusof, F.; Jamaludin, M.F.; et al. A review on biomedical implant materials and the effect of friction stir based techniques on their mechanical and tribological properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 17, 1054–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, B.W.K.; Yeow, C.-H.; Lim, J.H. A Critical Review on Factors Affecting the User Adoption of Wearable and Soft Robotics. Sensors 2023, 23, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Hao, L. A novel pneumatic soft sensor for measuring contact force and curvature of a soft gripper. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2017, 266, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzolai, B.; Cianchetti, M. Soft robotics: Technologies and systems pushing the boundaries of robot abilities. Sci. Robot. 2016, 1, eaah3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, C.; Peele, B.; Li, S.; Robinson, S.; Totaro, M.; Beccai, L.; Mazzolai, B.; Shepherd, R. Highly stretchable electroluminescent skin for optical signaling and tactile sensing. Science 2016, 351, 1071–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehner, M.; Truby, R.L.; Fitzgerald, D.W.; Mosadegh, B.; Whitesides, G.M.; Lewis, J.A.; Wood, R.J. An integrated design and fabrication strategy for entirely soft, autonomous robots. Nature 2016, 536, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, B.; Wang, D.; Tang, M. Wearable Pressure Sensor Array with Layer-by-Layer Assembled MXene Nanosheets/Ag Nanoflowers for Motion Monitoring and Human-Machine Interfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 48907–48916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareh, S.; Noh, Y. Low profile stretch sensor for soft wearable robotics. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Soft Robotics (RoboSoft), Livorno, Italy, 24–28 April 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 479–484. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, S.E.; Nagels, S.; Alagi, H.; Faller, L.-M.; Goury, O.; Morales-Bieze, T.; Zangl, H.; Hein, B.; Ramakers, R.; Deferme, W.; et al. A Model-Based Sensor Fusion Approach for Force and Shape Estimation in Soft Robotics. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 5621–5628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D. Grip Force and Slip Analysis in Robotic Grasp: New Stochastic Paradigm Through Sensor Data Fusion. In Sensors: Focus on Tactile Force and Stress Sensors; Gerardo, J., Lanceros-Mendez, S., Eds.; InTech: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-953-7619-31-2. [Google Scholar]

- ACRONAME. Sensors for Robotics–5 Common Types. Available online: https://acroname.com/blog/sensors-robotics-5-common-types#:~:text=The%20type%20of%20sensors%20used,of%20digital%20and%20analog%20watches (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Xia, Z.; Deng, Z.; Fang, B.; Yang, Y.; Sun, F. A review on sensory perception for dexterous robotic manipulation. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2022, 19, 17298806221095974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, J.S.; Evans, K.R.; Hebert, J.S.; Marasco, P.D.; Carey, J.P. The effect of biomechanical variables on force sensitive resistor error: Implications for calibration and improved accuracy. J. Biomech. 2016, 49, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florez, J.A.; Velasquez, A. Calibration of force sensing resistors (fsr) for static and dynamic applications. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE ANDESCON, Bogota, Colombia, 15–17 September 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Mao, B.; Li, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, K.; Cao, X.; Fan, Q.; Xu, M.; Liang, B.; Liu, H.; et al. Recent Progress in Advanced Tactile Sensing Technologies for Soft Grippers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2306249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Seyedi, M.; Cai, Z.; Lai, D. Force-Sensing Glove System for Measurement of Hand Forces during Motorbike Riding. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2015, 11, 545643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadir, S.K. Identification and Modeling of Sensing Capability of Force Sensing Resistor Integrated to E-Textile Structure. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 9770–9780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.S. Engineering Optimization Theory and Practice; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averta, G.; Barontini, F.; Valdambrini, I.; Cheli, P.; Bacciu, D.; Bianchi, M. Learning to Prevent Grasp Failure with Soft Hands: From Online Prediction to Dual-Arm Grasp Recovery. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4, 2100146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deimel, R.; Brock, O. A novel type of compliant and underactuated robotic hand for dexterous grasping. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2016, 35, 161–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, R.S.; Valle, M. Tactile Sensing: Definitions and Classification. In Robotic Tactile Sensing; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Choi, D.; Yang, S.; Kwon, J.-Y. Thermo and flex multi-functional array ionic sensor for a human adaptive device. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 36960–36966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdenebayar, U.; Park, J.-U.; Jeong, P.; Lee, K.-J. Obstructive Sleep Apnea Screening Using a Piezo-Electric Sensor. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilanizadehdizaj, G.; Aw, K.C.; Stringer, J.; Bhattacharyya, D. Facile fabrication of flexible piezo-resistive pressure sensor array using reduced graphene oxide foam and silicone elastomer. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2022, 340, 113549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, U.-H.; Jeong, D.-W.; Park, S.-M.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, H.W.; Kim, J.-M. Highly stretchable conductors and piezocapacitive strain gauges based on simple contact-transfer patterning of carbon nanotube forests. Carbon 2014, 80, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lin, S.; Liu, X.; Qin, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zang, J.; Zhao, X. Fatigue-resistant adhesion of hydrogels. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Xiong, X.; Yang, J.; Dickey, M.D. Liquid Metal Interdigitated Capacitive Strain Sensor with Normal Stress Insensitivity. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4, 2100201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, S.; Arunagirinathan, R.S. Silver Nanowires in Stretchable Resistive Strain Sensors. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinegger, A.; Wolfbeis, O.S.; Borisov, S.M. Optical Sensing and Imaging of pH Values: Spectroscopies, Materials, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 12357–12489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, P.; Li, G.; Yang, L.; Yu, W.; Meng, C.; Guo, S. A highly stretchable and ultra-sensitive strain sensing fiber based on a porous core–network sheath configuration for wearable human motion detection. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 12418–12430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, S.E.; Muhlbacher-Karrer, S.; Alagi, H.; Zangl, H.; Koyama, K.; Hein, B.; Duriez, C.; Smith, J.R. Proximity Perception in Human-Centered Robotics: A Survey on Sensing Systems and Applications. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2022, 38, 1599–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhong, H.; Tang, K.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Yi, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z. Soft Origami Optical-Sensing Actuator for Underwater Manipulation. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 7, 616128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin. Density Measurement Basics—Part 2. Available online: https://www.truedyne.com/density-measurement-basics-part-2/?lang=en (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Yan, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, B.; Zhao, J. A New Spiral-Type Inflatable Pure Torsional Soft Actuator. Soft Robot. 2018, 5, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayton, B.D.; Legrand, L.; Smith, J.R. An Electric Field Pretouch system for grasping and co-manipulation. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Anchorage, AK, USA, 3–7 May 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagi, H.; Navarro, S.E.; Mende, M.; Hein, B. A versatile and modular capacitive tactile proximity sensor. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Haptics Symposium (HAPTICS), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 8–11 April 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrman, M.; Kanade, T. Design of an Optical Proximity Sensor Using Multiple Cones of Light for Measuring Surface Shape; The Robotics Institute, Carnegie-Mellon University: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, R.A.; Wijaya, J. Object location and recognition using whisker sensors. In Proceedings of the Australasian Conference on Robotics and Automation 2003, Brisbane, Australia, 1–3 December 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, M.D.C.P.; Gomez, D.G.; Ranera, J.D.V.; Carrizo, J.M.V.; Ureña, J. Review of UAV positioning in indoor environments and new proposal based on US measurements. CEUR Workshop Proc. 2019, 2498, 267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Bazeille, S.; Lebastard, V.; Lanneau, S.; Boyer, F. Model based object localization and shape estimation using electric sense on underwater robots. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2017, 50, 5047–5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, Z.M.; Clever, H.M.; Gangaram, V.; Xing, E.; Turk, G.; Liu, C.K.; Kemp, C. Characterizing Multidimensional Capacitive Servoing for Physical Human-Robot Interaction. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 39, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavedo, F.; Esmaili, P.; Norgia, M.; Cavedo, F.; Esmaili, P.; Norgia, M. Electronic Safety System for Table Saw. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 8580–8587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, K.; Shimojo, M.; Ming, A.; Ishikawa, M. Integrated control of a multiple-degree-of-freedom hand and arm using a reactive architecture based on high-speed proximity sensing. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2019, 38, 1717–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, K.; Shimoyama, I. Slippage Sensing for Robot Foot. J. Robot. Soc. Jpn. 2017, 35, 664–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekine, T.; Wang, Y.-F.; Hong, J.; Takeda, Y.; Miura, R.; Watanabe, Y.; Abe, M.; Mori, Y.; Wang, Z.; Kumaki, D.; et al. Artificial Cutaneous Sensing of Object Slippage using Soft Robotics with Closed-Loop Feedback Process. Small Sci. 2021, 1, 2170007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshigawara, S.; Tsutsumi, T.; Shimizu, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Ming, A.; Ishikawa, M.; Shimojo, M. Highly sensitive sensor for detection of initial slip and its application in a multi-fingered robot hand. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1097–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Castanedo, F. A Review of Data Fusion Techniques. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 704504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, P.K. Multisensor data fusion. In Intelligent Problem Solving. Methodologies and Approaches; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.L.; Llinas, J. An introduction to multisensor data fusion. Proc. IEEE 1997, 85, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, C.; Genderen, J. Multisensor image fusion in remote sensing: Concepts, methods and applications. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1998, 19, 823–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.; Dolev, S.; Leshem, G. Sensor networks. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2014, 553, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasarathy, B. Sensor fusion potential exploitation-innovative architectures and illustrative applications. Proc. IEEE 1997, 85, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Sloep, P.; Hummel, H.G.K.; Koper, R. Improving the unreliability of competence information: An argumentation to apply information fusion in learning networks. Int. J. Contin. Eng. Educ. Life-Long Learn. (IJCEELL) 2009, 19, 1560–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Tian, Z.-Q.; Wang, Z.L. Flexible triboelectric generator. Nano Energy 2012, 1, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Wang, N.; Ma, J.; Jie, Y.; Zou, J.; Cao, X. Stretchable 3D polymer for simultaneously mechanical energy harvesting and biomimetic force sensing. Nano Energy 2018, 47, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baborowski, J. Microfabrication of Piezoelectric MEMS. J. Electroceramics 2004, 12, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalambides, A.; Bergbreiter, S. A novel all-elastomer MEMS tactile sensor for high dynamic range shear and normal force sensing. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2015, 25, 095009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudaayev, A.; Varol, H.A. Sensors for Robotic Hands: A Survey of State of the Art. IEEE Access 2015, 3, 1765–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Van Laerhoven, K. How to build smart appliances? IEEE Pers. Commun. 2001, 8, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Property Sensing | Related Figure | Working Principle | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Humidity |  | For properties related to humidity, the soft robotic sensor works by absorption and adsorption of water, which changes the permeability and impacts electrical current flow or conductivity by changed resistance. | [73] |

| Temperature |  | By changing the temperature conductivity, permeability, reference length increase, pneumatic pressure difference, etc., function could lead to electrical signals and produce results such as temperature. | [74] |

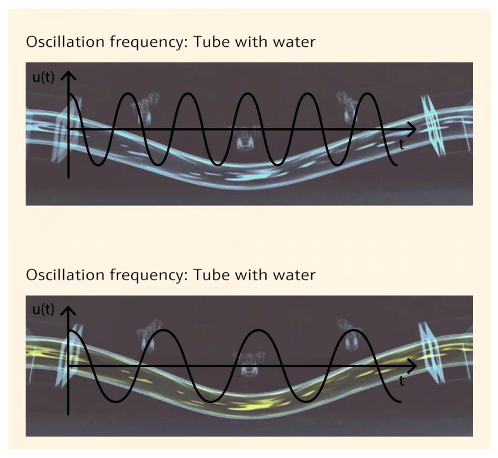

| Density |  | The resonator density method indirectly measures density by frequency. The liquid to be tested is placed in a resonance-vibrating tube. The oscillation frequency, which depends on liquid density and resonator rigidity, now indicates density. | [75] |

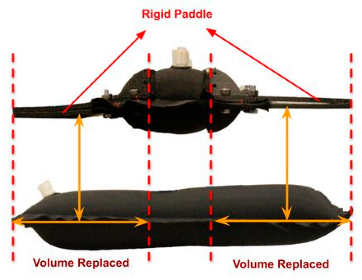

| Inflatability |  | By using inflatable sensor, it provides integrated information collected from fiber optic distributed strain sensors woven into Vectran/Kevlar restrain layer, and it has foam layer shielding. | [76] |

| Sensor Type | Material Used | Feature Size (nm) | Fabrication Techniques (Dry Etching) | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistive Sensors | SiO2, Polysilicon, Si3N4 | 10–100 | RIE, DRIE | Pressure sensors, touch screens, microphones |

| Capacitive Sensors | SiO2, Si, Metals (Au, Al) | Nanometer Range | RIE, Plasma Etching | Proximity sensors, accelerometers, humidity sensors |

| Piezoelectric Sensors | ZnO, PZT | Tens to Hundreds | RIE, Chemical Etching | Vibration sensors, ultrasound imaging |

| NEMS Devices | Si, SiC, Si3N4 | Nanoscale (device dependent) | DRIE, EBL + Plasma Etching | Microfluidic devices, gyroscopes |

| SPR Sensors | Metals (Au, Ag), Dielectrics (SiO2) | Nanoscale features (nanoholes, nanogratings) | EBL, FIB milling | Biosensing, chemical detection |

| Magnetic Sensors | Fe, Ni, Co alloys | 1–100 | Sputtering, Electroplating | Magnetic field sensors (compasses), medical imaging (MRI) |

| Gas Sensors | Metal oxides (e.g., WO3), Polymers | 10–1000 | Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) | Air quality monitoring, leak detection |

| Biosensors | Enzymes, Antibodies, Nucleic Acids | Varies (often larger than nano range) | Photolithography, Inkjet Printing | Medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring |

| Temperature Sensors | Platinum (Pt), Silicon (Si) | 10–1000 | Thin-film Deposition, Lithography | Temperature control systems, fire alarms |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rana, M.T.; Islam, M.S.; Rahman, A. Human-Centered Sensor Technologies for Soft Robotic Grippers: A Comprehensive Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 1508. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051508

Rana MT, Islam MS, Rahman A. Human-Centered Sensor Technologies for Soft Robotic Grippers: A Comprehensive Review. Sensors. 2025; 25(5):1508. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051508

Chicago/Turabian StyleRana, Md. Tasnim, Md. Shariful Islam, and Azizur Rahman. 2025. "Human-Centered Sensor Technologies for Soft Robotic Grippers: A Comprehensive Review" Sensors 25, no. 5: 1508. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051508

APA StyleRana, M. T., Islam, M. S., & Rahman, A. (2025). Human-Centered Sensor Technologies for Soft Robotic Grippers: A Comprehensive Review. Sensors, 25(5), 1508. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051508