Filament Type Recognition for Additive Manufacturing Using a Spectroscopy Sensor and Machine Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Multi-Spectral Sensor

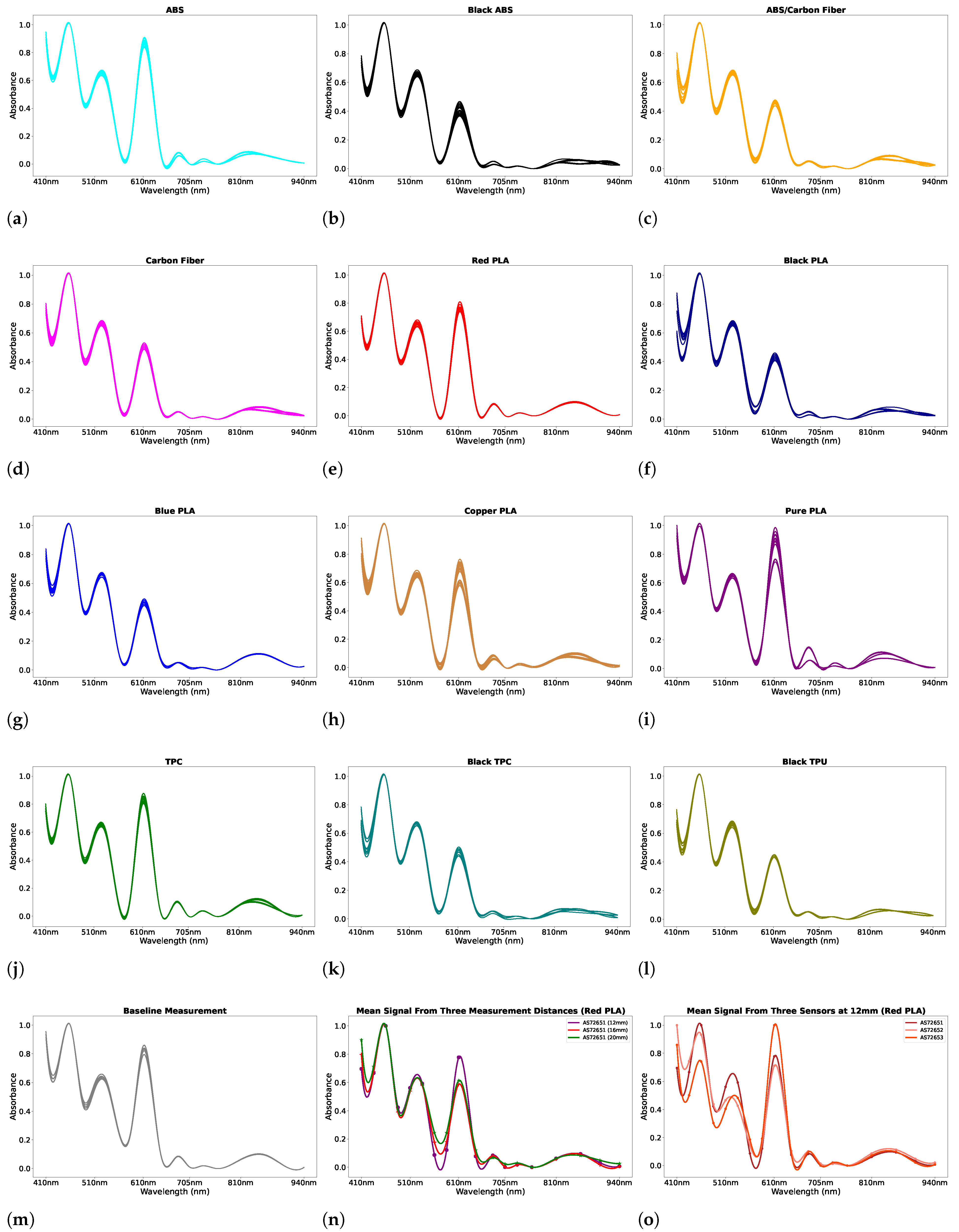

2.2. Filaments Used for Data Collection

2.3. Compact Filament Recognition Module and Data Collection

2.4. Data Collection Process

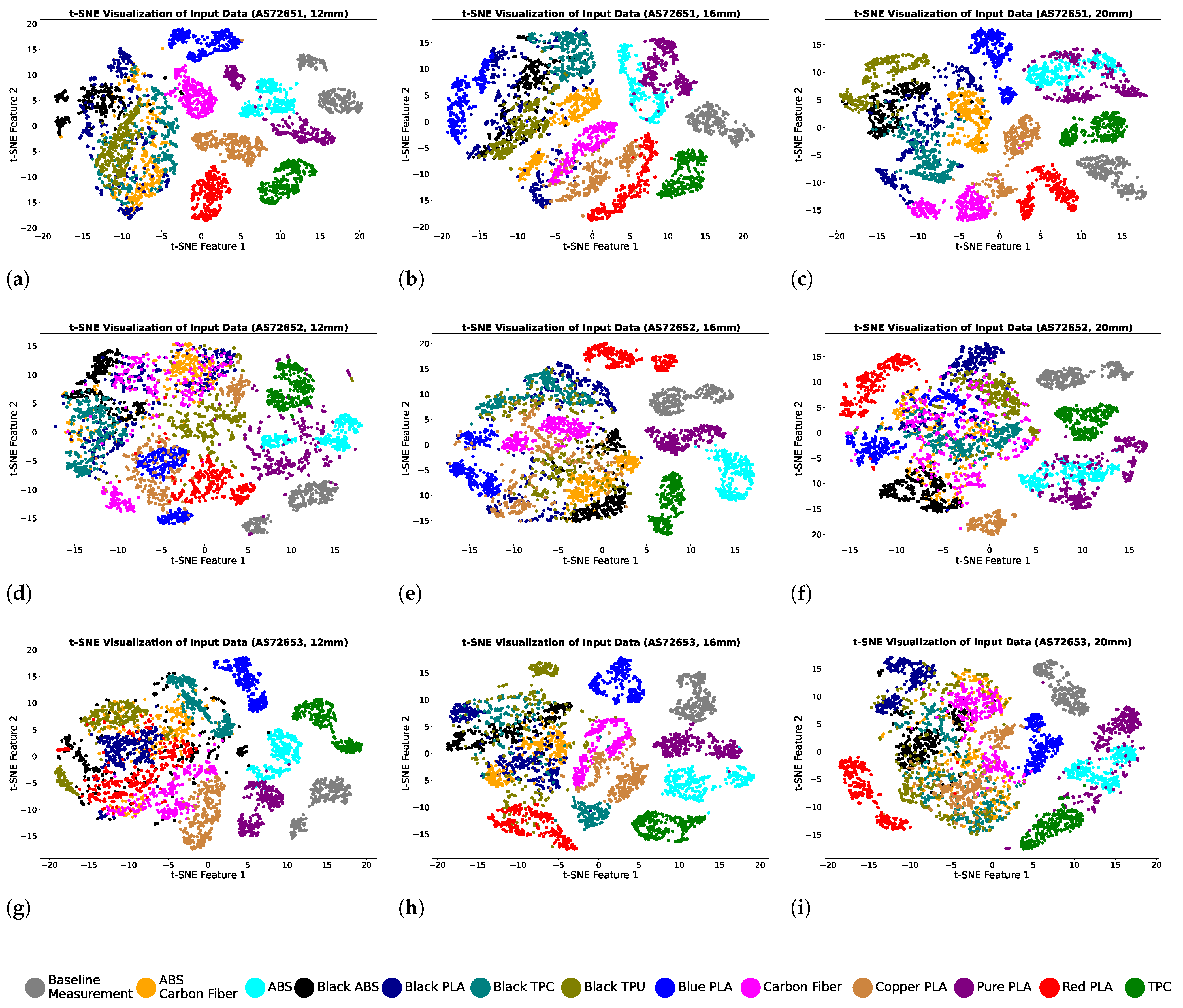

2.5. Machine Learning Procedure for Filament Recognition

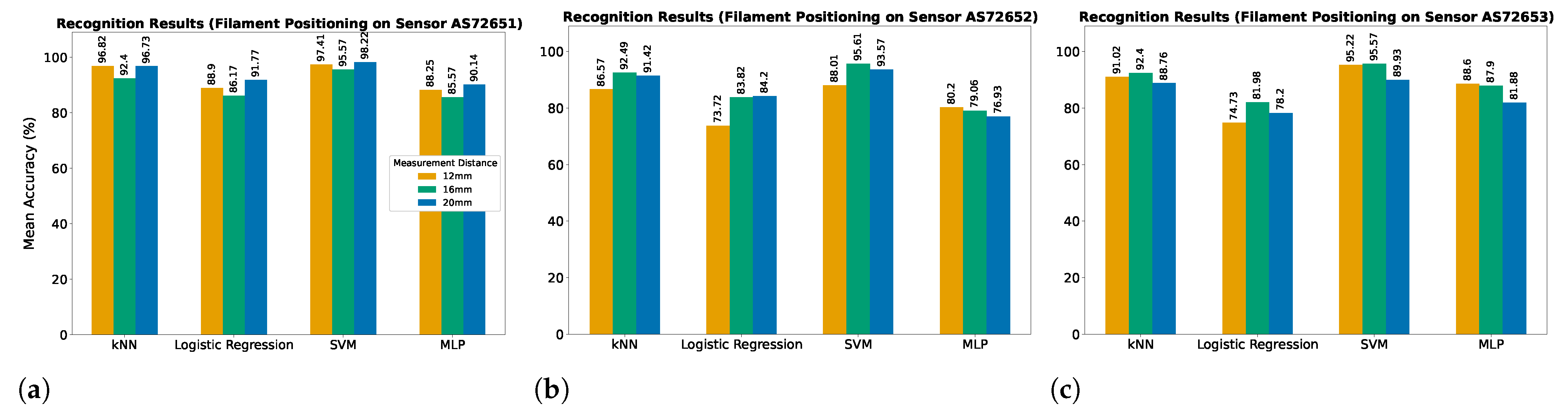

3. Experiments and Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.; Jiang, M.; Zhou, Z.; Gou, J.; Hui, D. 3D printing of polymer matrix composites: A review and prospective. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 110, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathies, T.; Senthil, P.; Anoop, M. A review on advancements in applications of fused deposition modelling process. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2020, 26, 669–687. [Google Scholar]

- Daminabo, S.C.; Goel, S.; Grammatikos, S.A.; Nezhad, H.Y.; Thakur, V.K. Fused deposition modeling-based additive manufacturing (3D printing): Techniques for polymer material systems. Mater. Today Chem. 2020, 16, 100248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fico, D.; Rizzo, D.; Casciaro, R.; Esposito Corcione, C. A review of polymer-based materials for fused filament fabrication (FFF): Focus on sustainability and recycled materials. Polymers 2022, 14, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Roan Eagle, I.N.; Yodo, N. A review on filament materials for fused filament fabrication. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2021, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Fu, Y.F. A short survey of sustainable material extrusion additive manufacturing. Aust. J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 21, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh Alghamdi, S.; John, S.; Roy Choudhury, N.; Dutta, N.K. Additive manufacturing of polymer materials: Progress, promise and challenges. Polymers 2021, 13, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colorado, H.A.; Mendoza, D.E.; Valencia, F.L. A combined strategy of additive manufacturing to support multidisciplinary education in arts, biology, and engineering. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2021, 30, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Lee, H. Recent advances in multi-material additive manufacturing: Methods and applications. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifvianto, B.; Satiti, B.E.; Salim, U.A.; Suyitno; Nuryanti, A.; Mahardika, M. Mechanical properties of the FFF sandwich-structured parts made of PLA/TPU multi-material. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 7, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espalin, D.; Alberto Ramirez, J.; Medina, F.; Wicker, R. Multi-material, multi-technology FDM: Exploring build process variations. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2014, 20, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baca, D.; Ahmad, R. The impact on the mechanical properties of multi-material polymers fabricated with a single mixing nozzle and multi-nozzle systems via fused deposition modeling. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 106, 4509–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanov, S.; Alkunte, S.; Rajeshirke, M.; Gupta, A.; Huseynov, O.; Fidan, I.; Alifui-Segbaya, F.; Rennie, A. Review on additive manufacturing of multi-material parts: Progress and challenges. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2021, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L.; Silva, A.; Carneiro, O. Multi-material 3D printing: The relevance of materials affinity on the boundary interface performance. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 23, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermolai, V.; Sover, A. Multi-material 3D Printed Interfaces. Influencing Factors and Design Considerations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Reliable Systems Engineering, Bucharest, Romania, 7 September 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Shaukat, U.; Rossegger, E.; Schlögl, S. A review of multi-material 3D printing of functional materials via vat photopolymerization. Polymers 2022, 14, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, Z.C.; Christ, J.F. Printing polymer blends through in situ active mixing during fused filament fabrication. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburrino, F.; Graziosi, S.; Bordegoni, M. The influence of slicing parameters on the multi-material adhesion mechanisms of FDM printed parts: An exploratory study. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2019, 14, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Ramoni, M.; Yodo, N. A Survey on Fused Filament Fabrication to Produce Functionally Gradient Materials. Materials 2024, 17, 3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tan, X.P.; Tor, S.B.; Lim, C. Machine learning in additive manufacturing: State-of-the-art and perspectives. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleff, A.; Küster, B.; Stonis, M.; Overmeyer, L. Process monitoring for material extrusion additive manufacturing: A state-of-the-art review. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 6, 705–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, O.A.; Masood, S.H.; Bhowmik, J.L. Influence of processing parameters on creep and recovery behavior of FDM manufactured part using definitive screening design and ANN. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2017, 23, 998–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Hu, G.; Li, X.; Xu, X.; Zheng, P.; Stringer, J. Analysis and prediction of printable bridge length in fused deposition modelling based on back propagation neural network. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2019, 14, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, O.A.; Masood, S.H.; Bhowmik, J.L. Investigation of dynamic elastic deformation of parts processed by fused deposition modeling additive manufacturing. Adv. Prod. Eng. Manag. 2016, 11, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.K.; Equbal, A.; Toppo, V.; Ohdar, R.; Mahapatra, S. An investigation on sliding wear of FDM built parts. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2012, 5, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.K.; Ohdar, R.K.; Mahapatra, S.S. Experimental investigation and empirical modelling of FDM process for compressive strength improvement. J. Adv. Res. 2012, 3, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Downey, A.; Yuan, L.; Pratt, A.; Balogun, Y. In situ monitoring for fused filament fabrication process: A review. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 38, 101749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, G.; Assaf, T.; Martinez-Hernandez, U. Towards Low-cost Plastic Recognition using Machine Learning and Multi-spectra Near-infrared Sensor. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE SENSORS, Vienna, Austria, 29 October–1 November 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Hernandez, U.; West, G.; Assaf, T. Low-Cost Recognition of Plastic Waste Using Deep Learning and a Multi-Spectral Near-Infrared Sensor. Sensors 2024, 24, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart 18-Channel VIS to NIR Spectral 3-Sensor Chipset with Electronic Shutter. Available online: https://ams.com/documents/20143/36005/AS7265x_DS000612_1-00.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Sparkfun Triad Spectroscopy Sensor—AS7265x (Qwiic). Available online: https://www.sparkfun.com/products/15050 (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Van der Maaten, L.; Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2008, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- Behera, B.; Kumaravelan, G.; Kumar, P. Performance evaluation of deep learning algorithms in biomedical document classification. In Proceedings of the 2019 11th International Conference on Advanced Computing (ICoAC), Chennai, India, 18–20 December 2019; pp. 220–224. [Google Scholar]

- Male, J.; Martinez-Hernandez, U. Deep learning based robot cognitive architecture for collaborative assembly tasks. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2023, 83, 102572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al, G.A.; Martinez-Hernandez, U. Multimodal barometric and inertial measurement unit-based tactile sensor for robot control. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 23, 1962–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Best Classifier | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kNN | 97.20% | 97.39% | 97.20% | 97.16% |

| Logistic Regression | 93.12% | 93.10% | 93.12% | 93.04% |

| SVM | 98.95% | 98.95% | 98.95% | 98.94% |

| MLP | 92.65% | 93.30% | 92.65% | 92.69% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al, G.A.; Martinez-Hernandez, U. Filament Type Recognition for Additive Manufacturing Using a Spectroscopy Sensor and Machine Learning. Sensors 2025, 25, 1543. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051543

Al GA, Martinez-Hernandez U. Filament Type Recognition for Additive Manufacturing Using a Spectroscopy Sensor and Machine Learning. Sensors. 2025; 25(5):1543. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051543

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl, Gorkem Anil, and Uriel Martinez-Hernandez. 2025. "Filament Type Recognition for Additive Manufacturing Using a Spectroscopy Sensor and Machine Learning" Sensors 25, no. 5: 1543. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051543

APA StyleAl, G. A., & Martinez-Hernandez, U. (2025). Filament Type Recognition for Additive Manufacturing Using a Spectroscopy Sensor and Machine Learning. Sensors, 25(5), 1543. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25051543