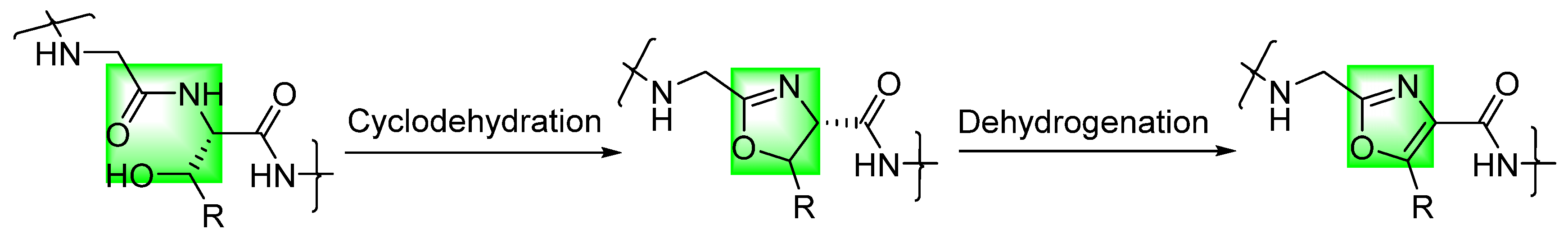

Naturally Occurring Oxazole-Containing Peptides

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Short Linear Peptides

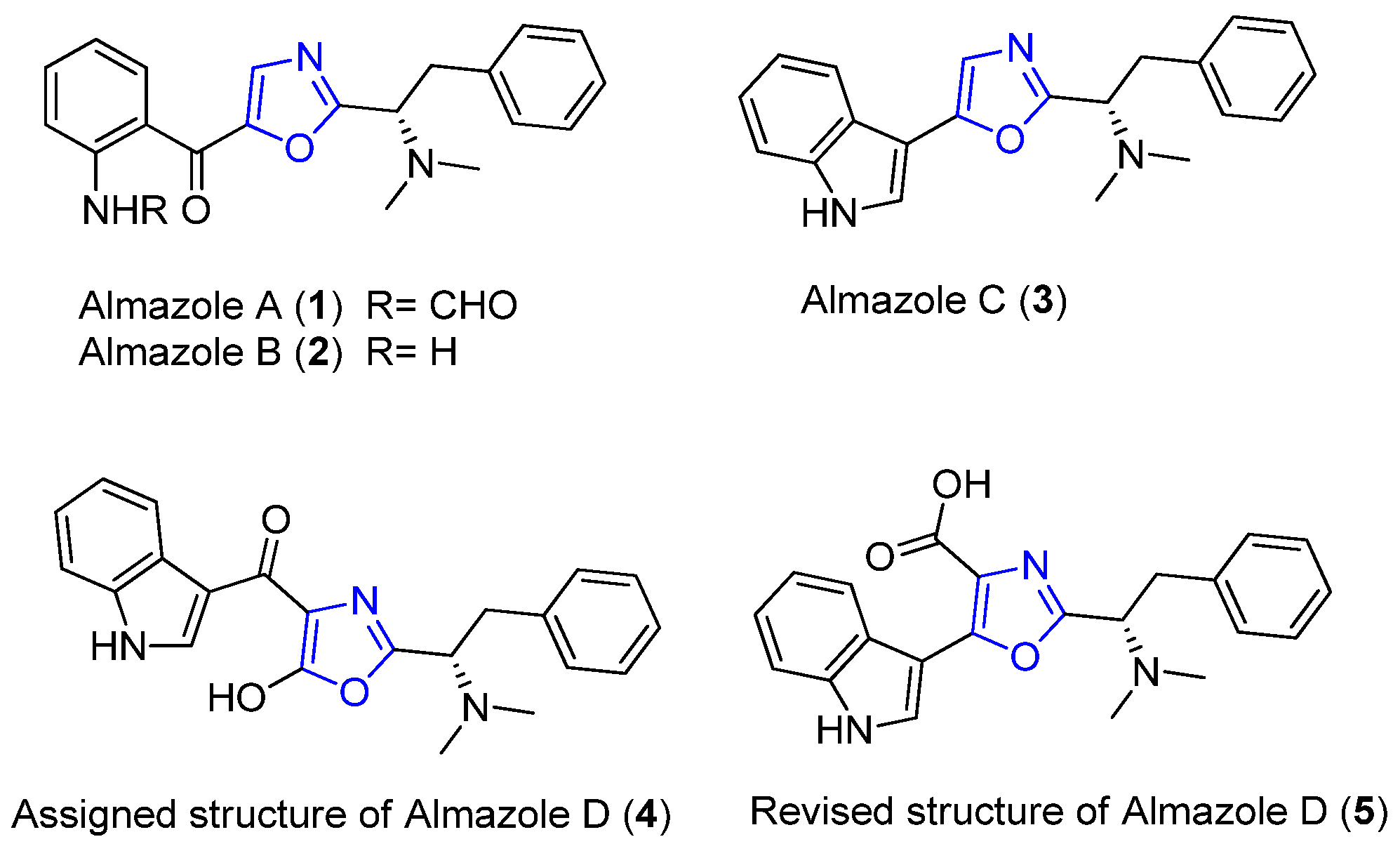

2.1. Almazoles A–D

2.2. Martefragin A

2.3. Muscoride A

3. Long Linear Peptides

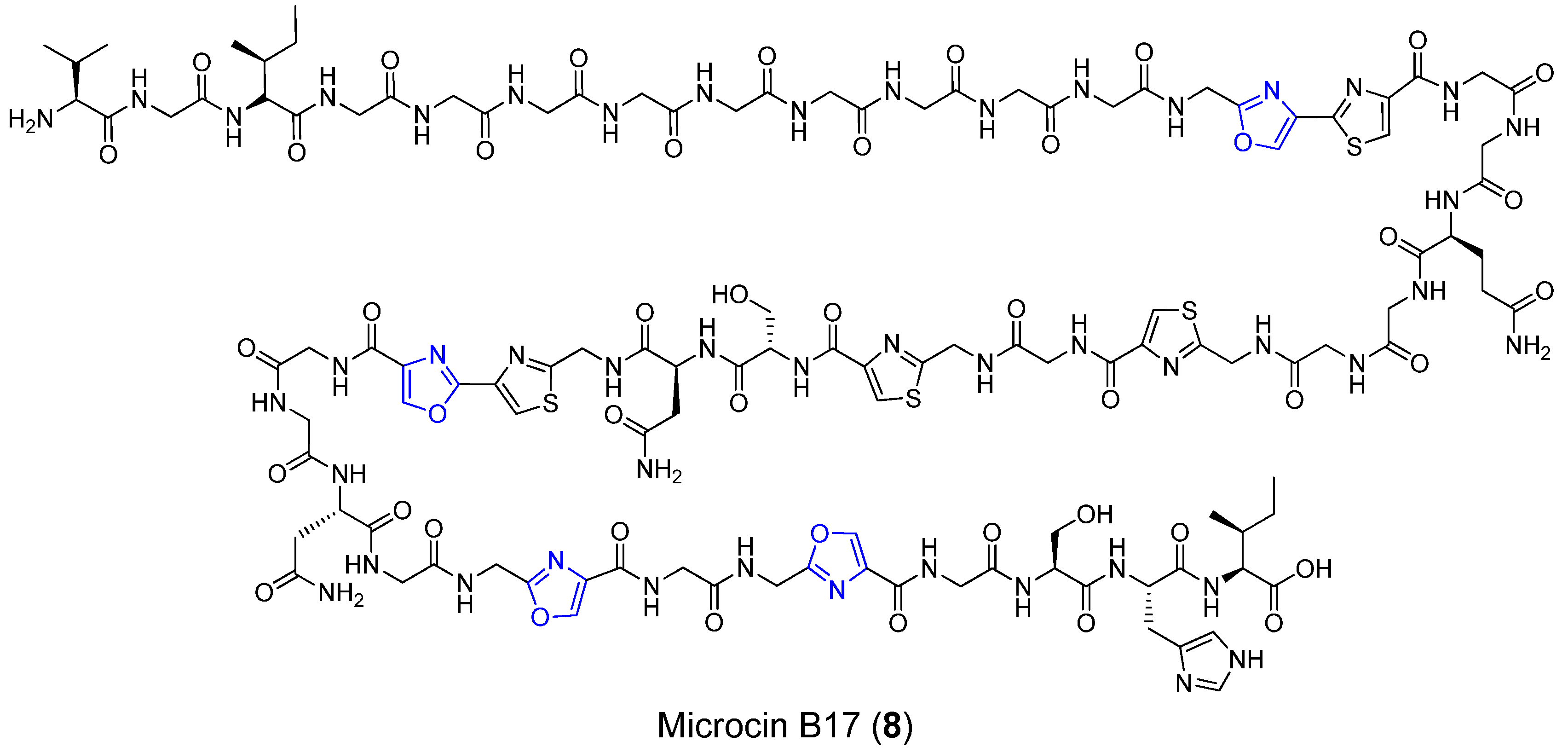

3.1. Microcin B17

3.2. Plantazolicins A and B

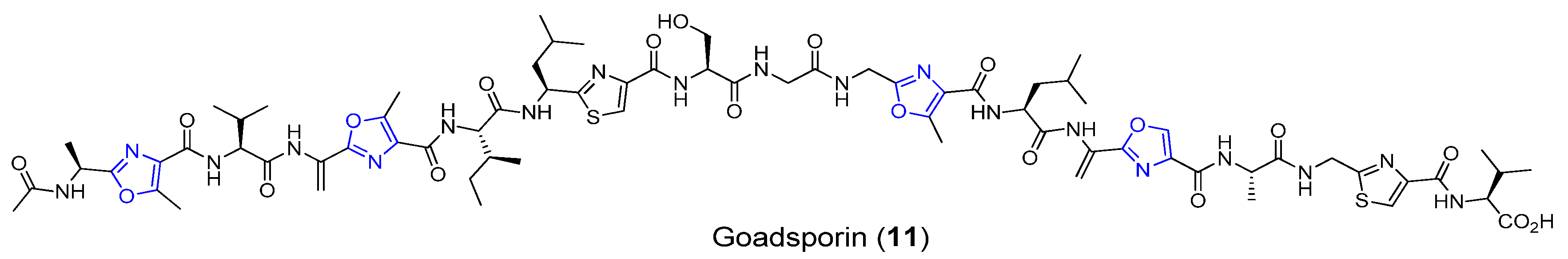

3.3. Goadsporin

4. Cyclic Peptides

4.1. Bistratamides C, D, G, H, I, M, and N

4.2. Dendroamides A–C

4.3. Nostocyclamides

4.4. Tenuecyclamides A–D

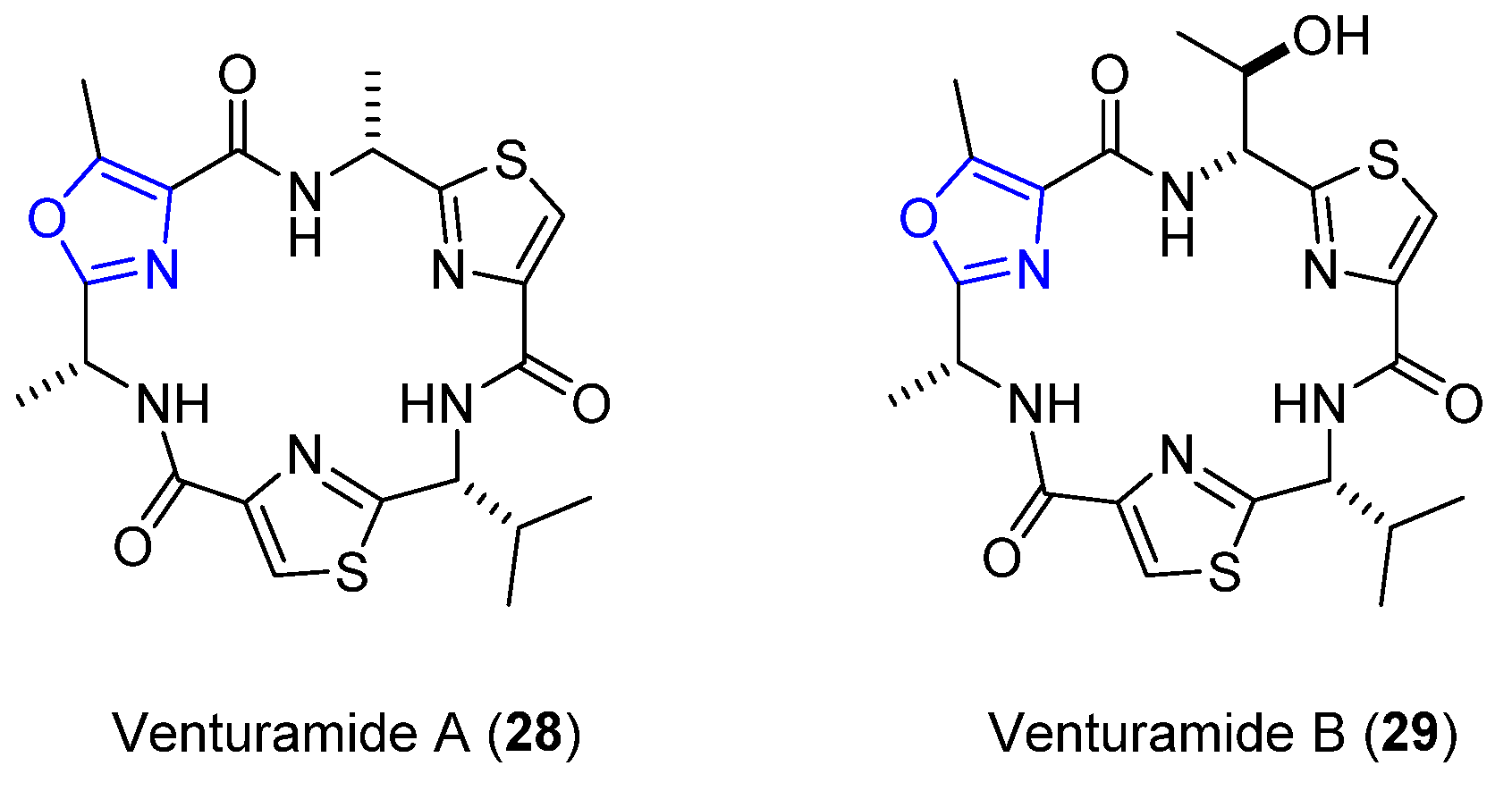

4.5. Venturamides A and B

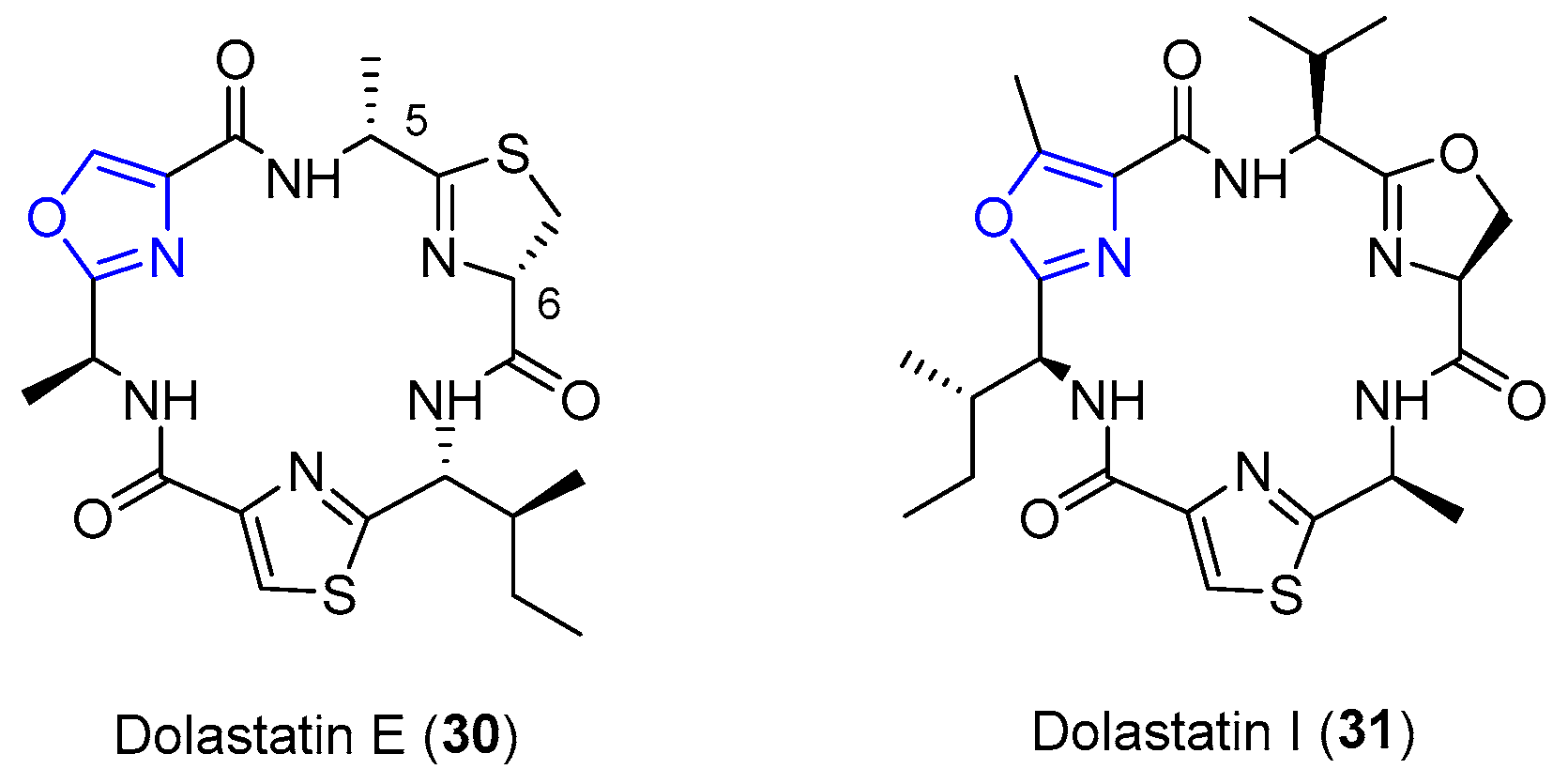

4.6. Dolastatins E and I

4.7. Raocyclamides A–B

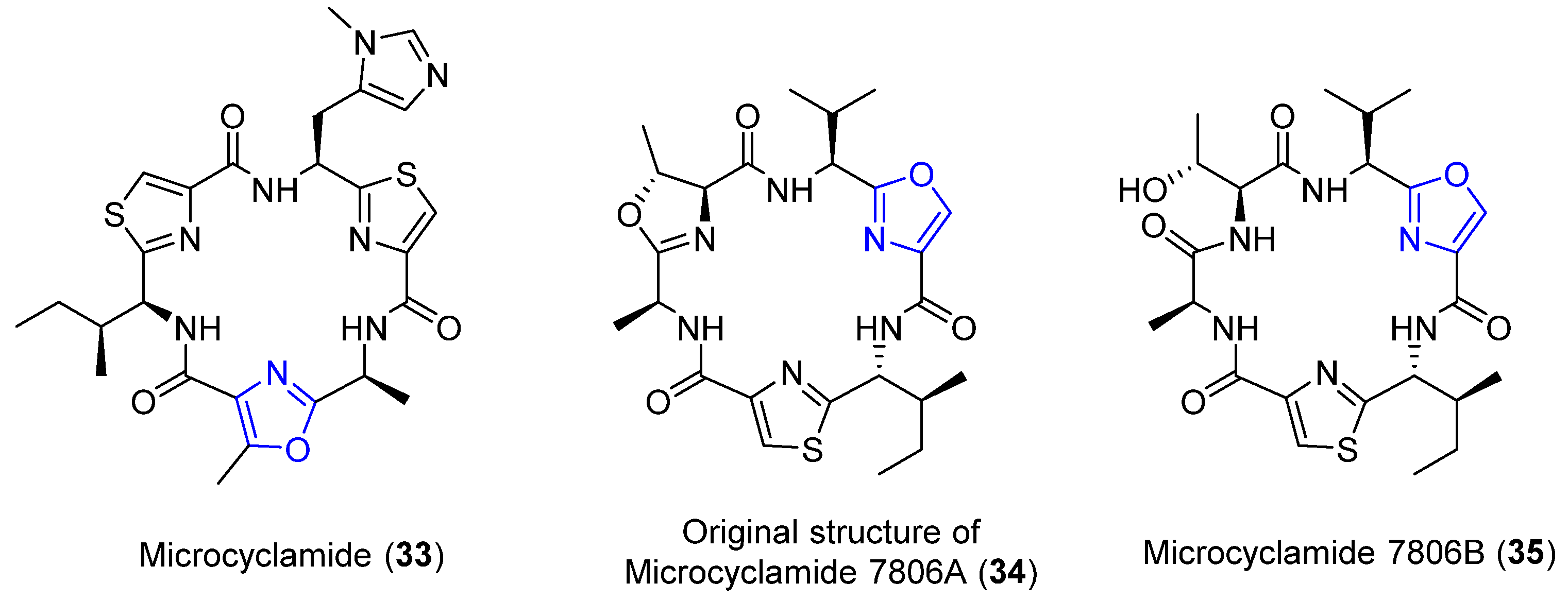

4.8. Microcyclamides

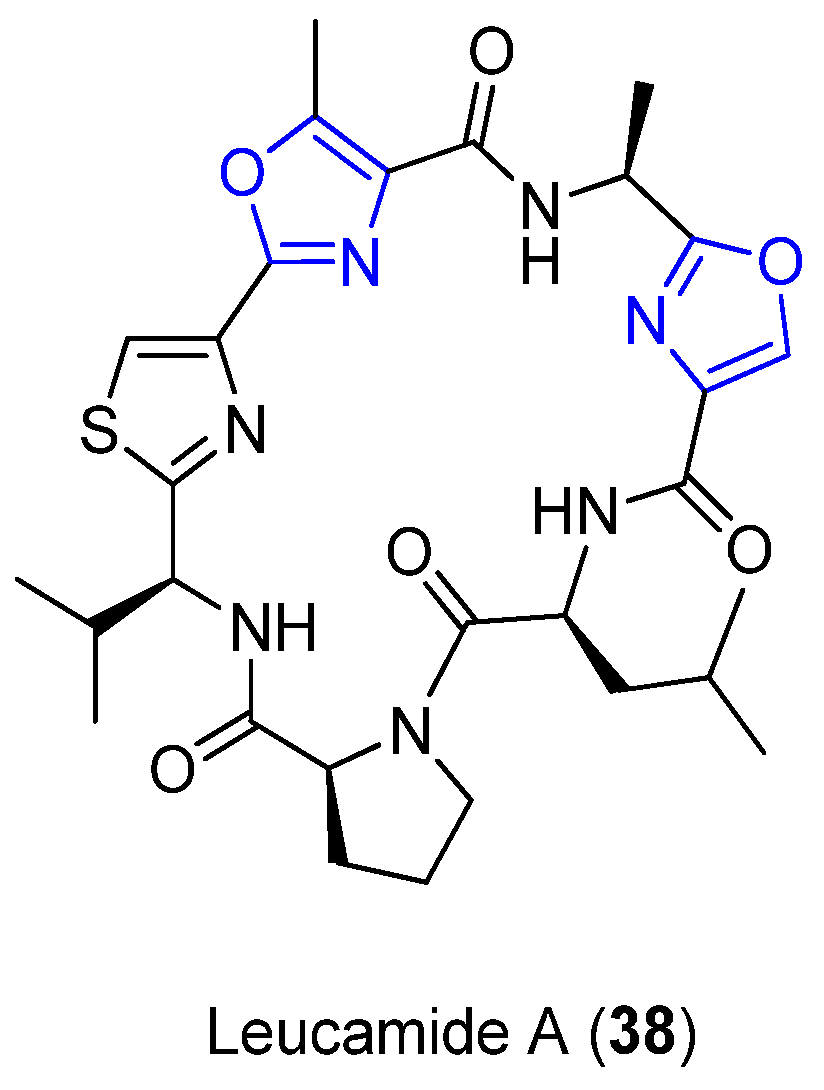

4.9. Leucamide A

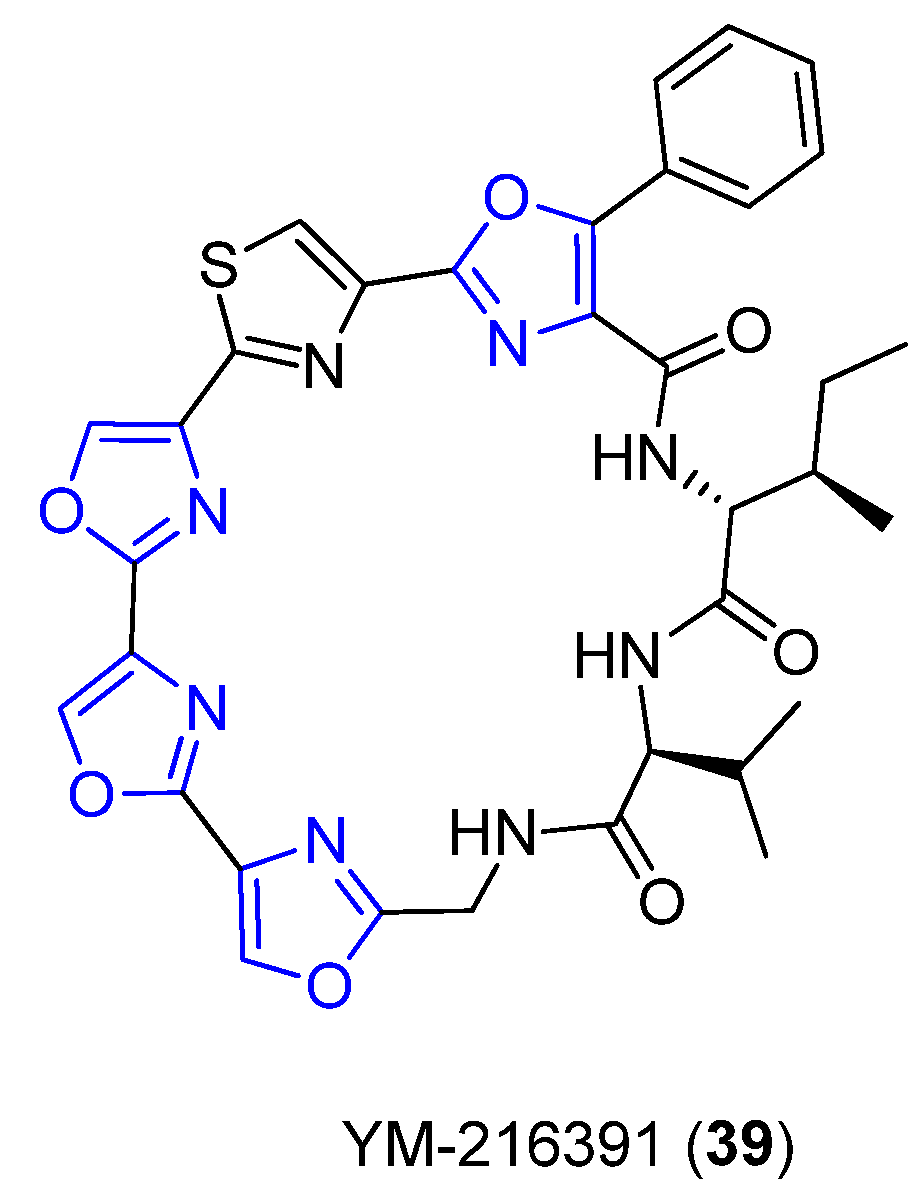

4.10. YM-216391

4.11. Urukthapelstatin A

4.12. Mechercharmycins A and B

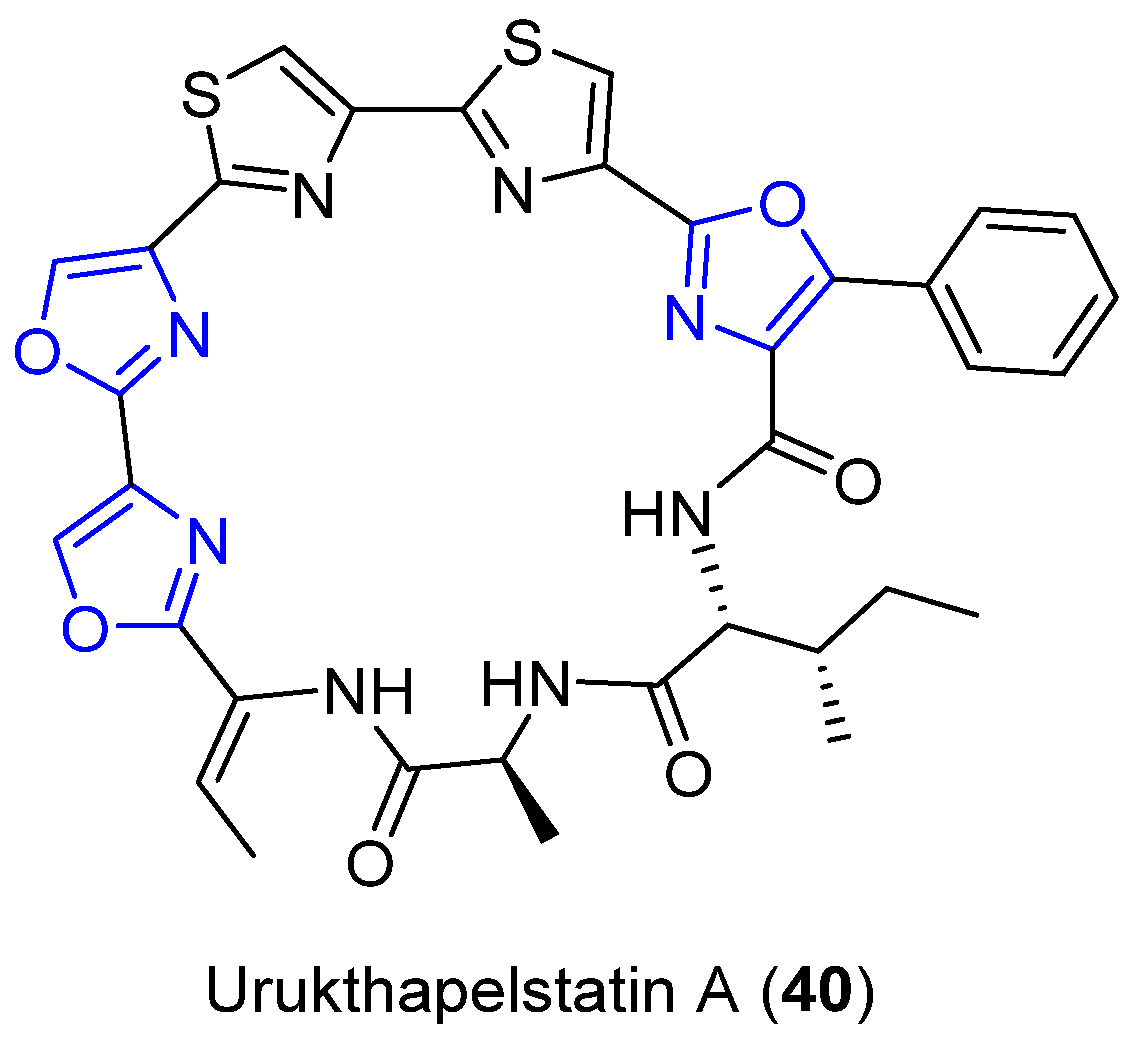

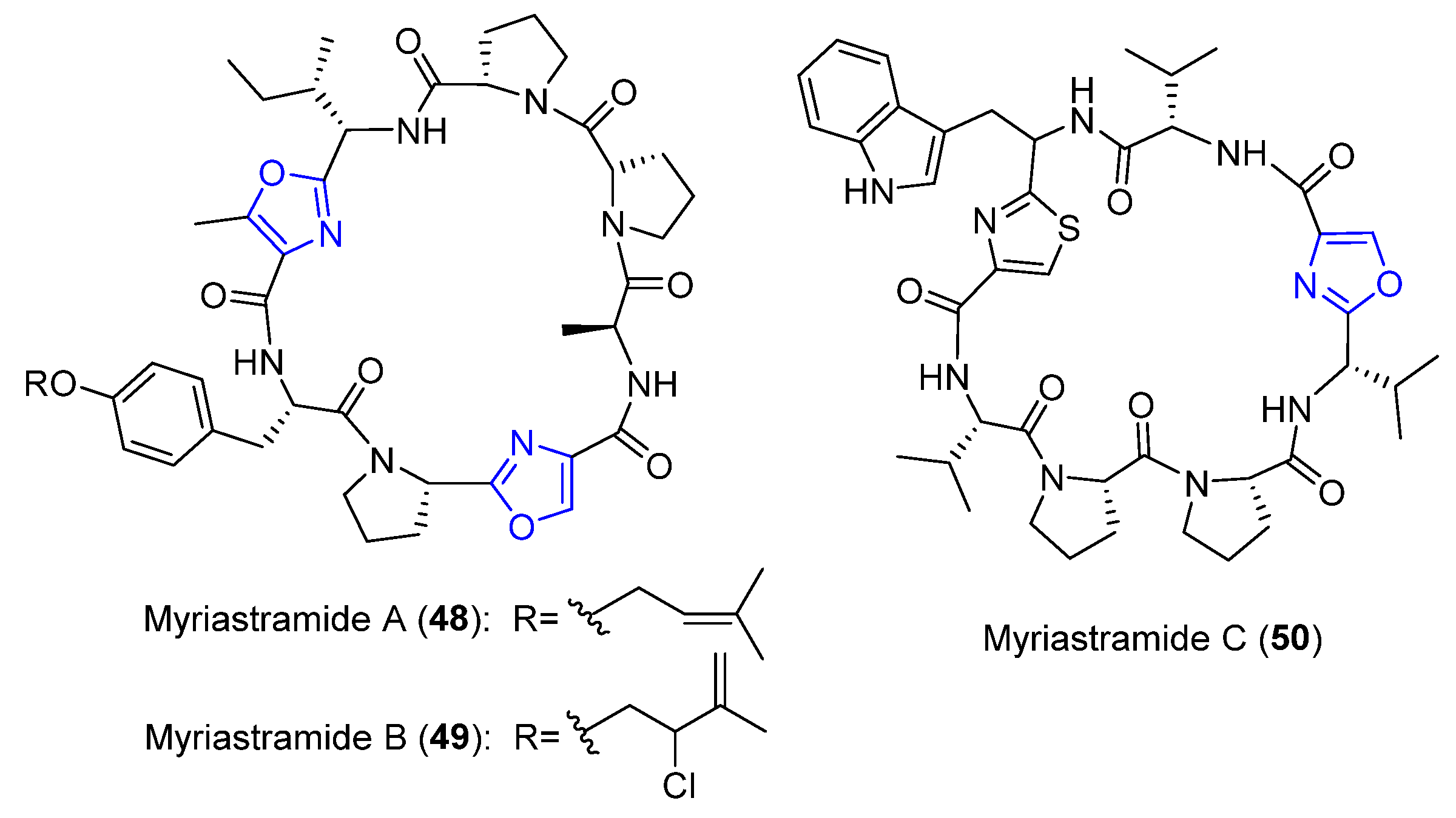

4.13. Haliclonamides A–E

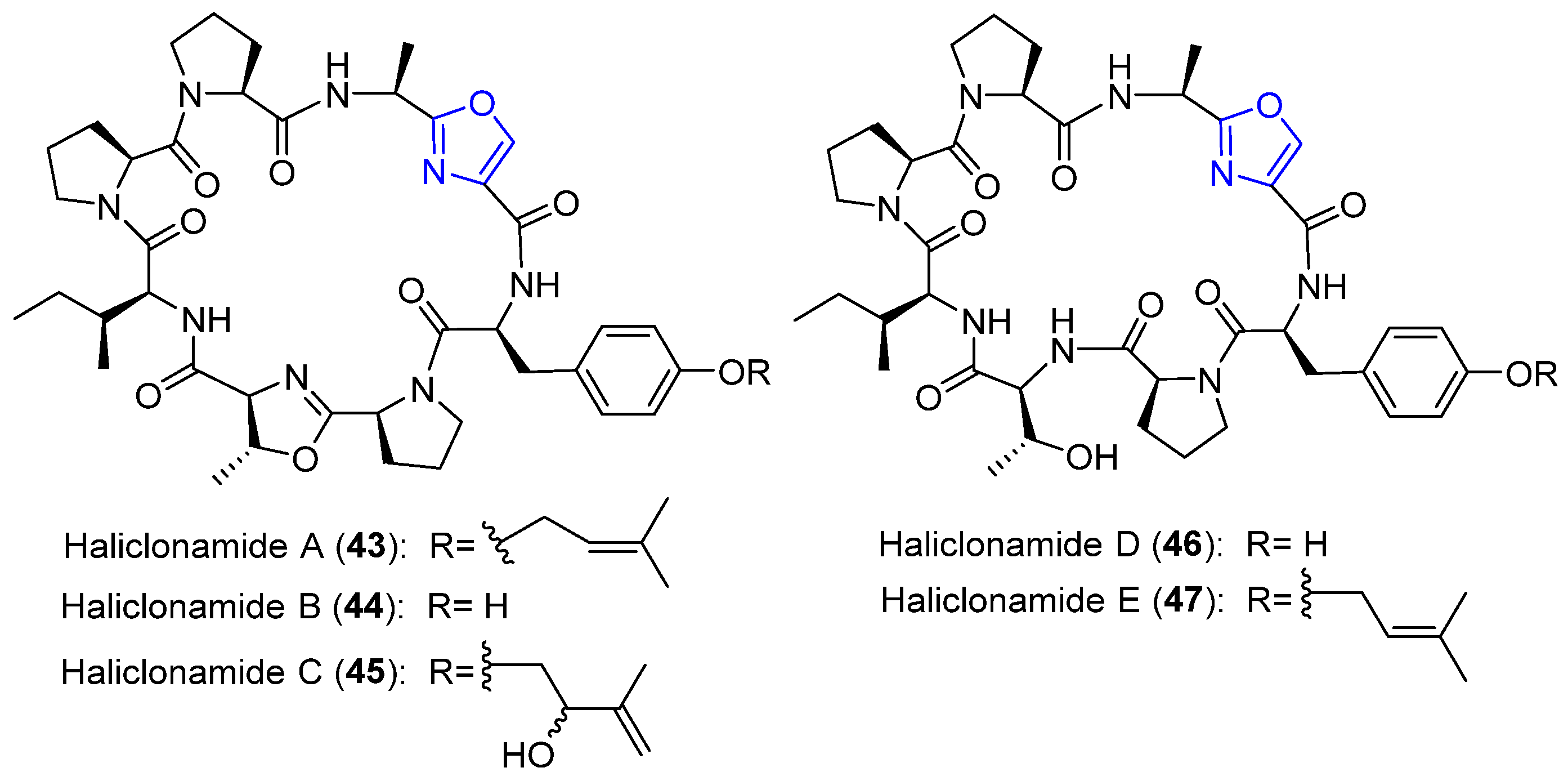

4.14. Myriastramides A–C

4.15. Wewakazoles

4.16. Keramamides B–E

5. Bicyclic Peptides

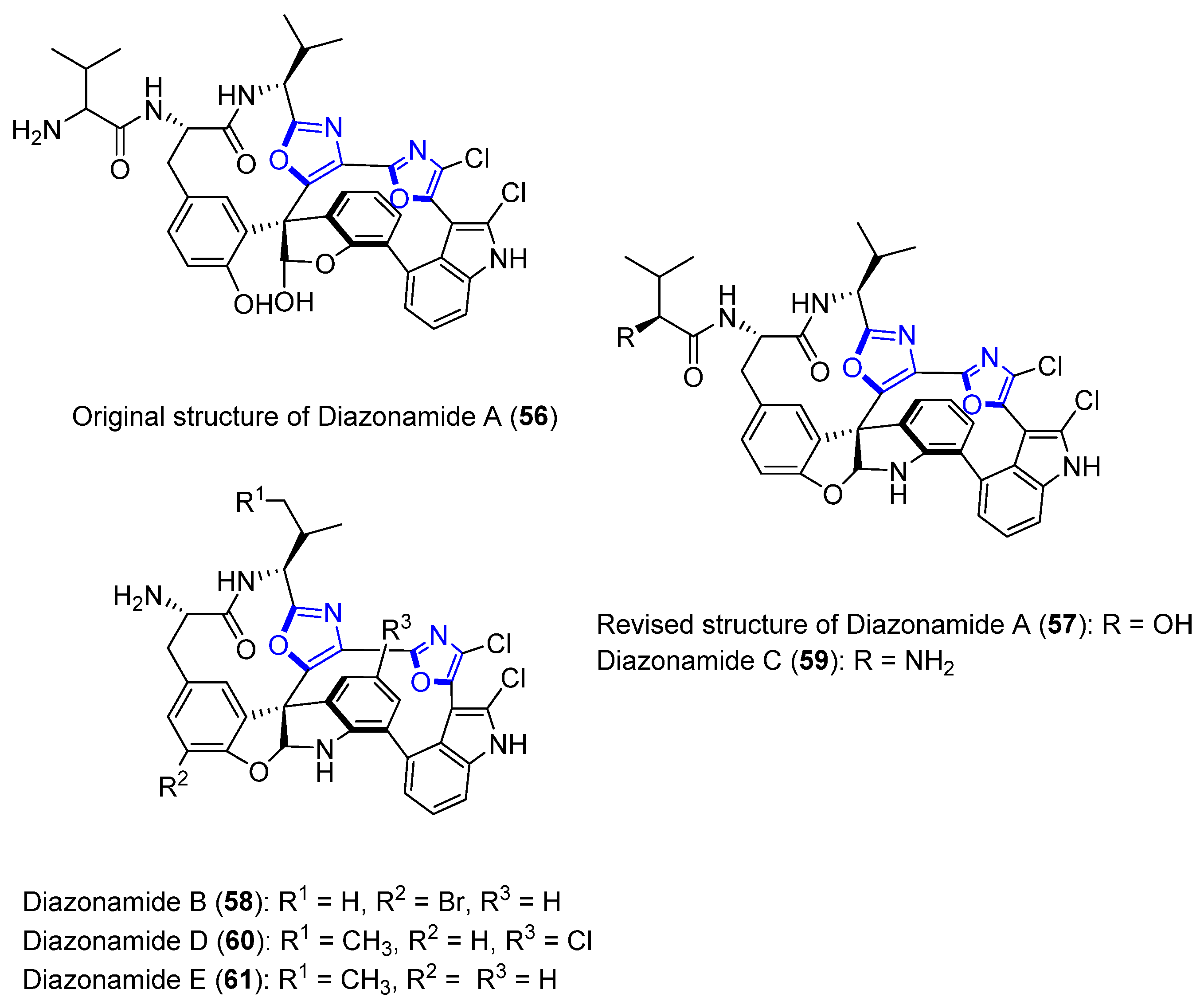

Diazonamides A–E

6. Thiopeptides

6.1. Baringolin

6.2. Thioxamycin and Thioactin

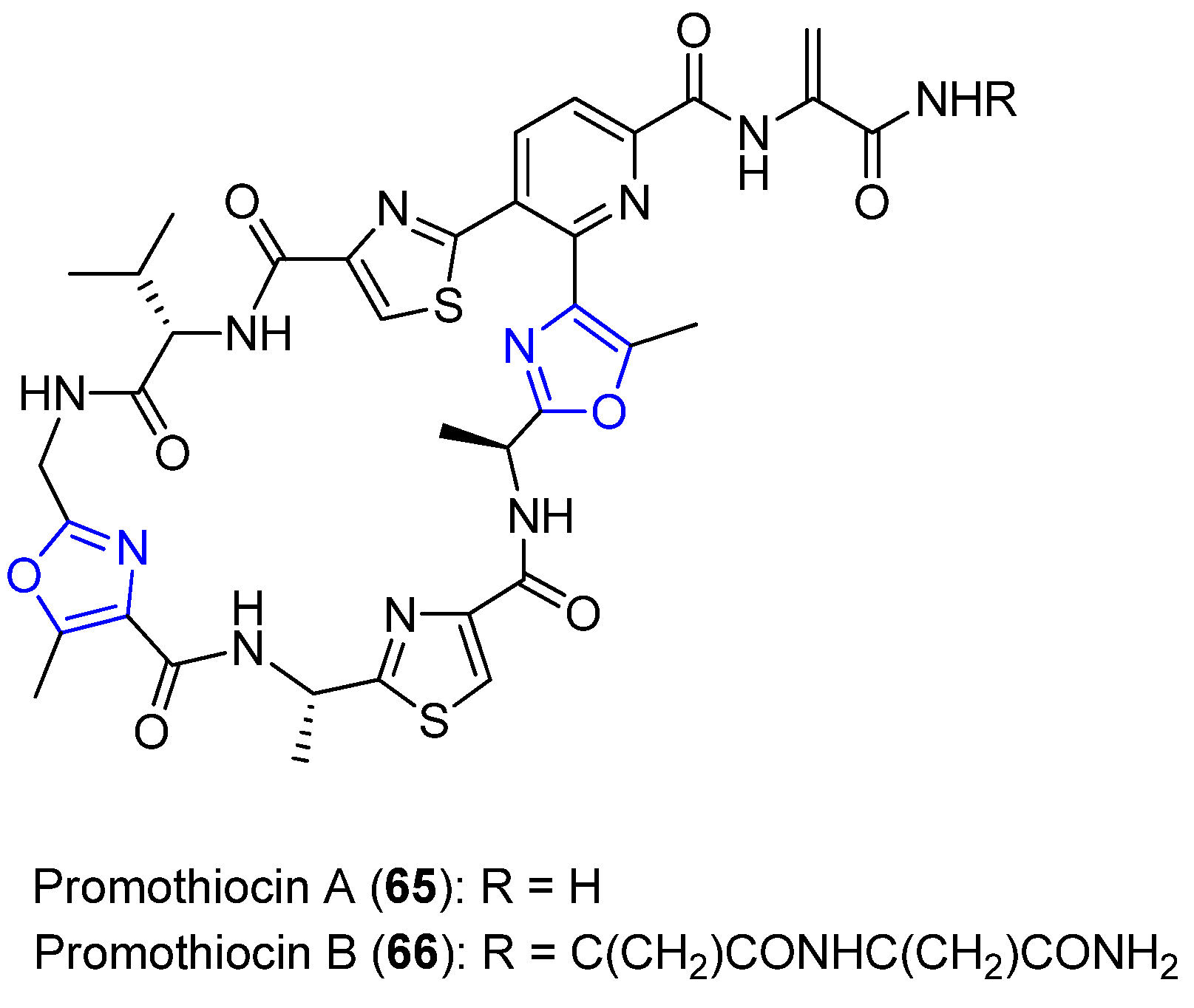

6.3. Promothiocins A and B

6.4. Sulfomycins I–III

6.5. A10255B, E, and G

6.6. Methylsulfomycin I

7. Overview

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, L. Peptide-based drug development. Mod. Chem. Appl. 2013, 1, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosgerau, K.; Hoffmann, T. Peptide therapeutics: Current status and future directions. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vlieghe, P.; Lisowski, V.; Martinez, J.; Khrestchatisky, M. Synthetic therapeutic peptides: Science and market. Drug Discov. Today 2010, 15, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craik, D.J.; Fairlie, D.P.; Liras, S.; Price, D. The future of peptide-based drugs. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2013, 81, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murru, S.; Dooley, C.T.; Nefzi, A. Parallel synthesis of bis-oxazole peptidomimetics. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 7062–7064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelay-Gimeno, M.; Glas, A.; Koch, O.; Grossmann, T.N. Structure-based design of inhibitors of protein–protein interactions: Nimicking peptide binding epitopes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 8896–8927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.S.; Kelleher, N.L.; Milne, J.C.; Walsh, C.T. In vivo processing and antibiotic activity of microcin B17 analogs with varying ring content and altered bisheterocyclic sites. Chem. Biol. 1999, 6, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oku, N.; Adachi, K.; Matsuda, S.; Kasai, H.; Takatsuki, A.; Shizuri, Y. Ariakemicins A and B, novel polyketide-peptide antibiotics from a marine gliding bacterium of the genus Rapidithrix. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 2481–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, H.; Williams, H.E.; Moody, C.J. Total synthesis of the posttranslationally modified polyazole peptide antibiotic plantazolicin A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 15147–15151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehraus, S.; König, G.M.; Wright, A.D.; Woerheide, G. Leucamide A: A new cytotoxic heptapeptide from the Australian sponge Leucetta microraphis. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 4989–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linington, R.G.; González, J.; Urena, L.-D.; Romero, L.I.; Ortega-Barría, E.; Gerwick, W.H. Venturamides A and B: Antimalarial constituents of the panamanian marine Cyanobacterium Oscillatoria sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorova, A.K.; Juettner, F.; Linden, A.; Pluess, T.; von Philipsborn, W. Nostocyclamide: A new macrocyclic, thiazole-containing allelochemical from Nostoc sp. 31 (cyanobacteria). J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 7891–7895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.A.V.; Al-Lihaibi, S.S.; Alarif, W.M.; Abdel-Lateff, A.; Nogata, Y.; Washio, K.; Morikawa, M.; Okino, T. Wewakazole B, a cytotoxic cyanobactin from the Cyanobacterium Moorea producens collected in the Red sea. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 1213–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolyar, I.V.; Yudin, A.K.; Nenajdenko, V.G. Heteroaryl rings in peptide macrocycles. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 10032–10240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turchi, I.J. Oxazole chemistry. A review of recent advances. Ind. Eng. Chem. Prod. Res. Dev. 1981, 20, 32–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilvi, S.; Singh, K.S. Synthesis of oxazole, oxazoline and isoxazoline derived marine natural products: A review. Curr. Org. Chem. 2016, 20, 898–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Bisht, A.S.; Juyal, D. Systematic scientific study of 1, 3-oxazole derivatives as a useful lead for pharmaceuticals: A review. Pharma Innov. J. 2017, 6, 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- N’Diaye, I.; Guella, G.; Chiasera, G.; Mancini, I.; Pietra, F. Almazole A and almazole B, unusual marine alkaloids of an unidentified red seaweed of the family delesseriaceae from the coasts of Senegal. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 4827–4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’Diaye, I.; Guella, G.; Mancini, I.; Pietra, F. Almazole D, a new type of antibacterial 2, 5-disubstituted oxazolic dipeptide from a red alga of the coast of Senegal. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 3049–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guella, G.; Mancini, I.; Pietra, F. Almazole C, a new indole alkaloid bearing an unusually 2, 5-disubstituted oxazole moiety, and its putative biogenetic peptidic precursors, from a senegalese delesseriacean seaweed. Helv. Chim. Acta 1994, 77, 1999–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, F.; Hashimoto, M.; Tonsiengsom, S.; Yakushijin, K.; Horne, D.A. Synthesis of 5-(3-indolyl) oxazole natural products. Structure revision of Almazole D. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 4888–4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lade, D.M.; Krishna, V.S.; Sriram, D.; Rode, H.B. A Facile synthesis and antituberculosis properties of almazole D and its enantiomer. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 1250–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Matsunaga, T.; Hasegawa, C.; Saito, H.; Fujita, D.; Kiuchi, F.; Tsuda, Y. Martefragin A, a novel indole alkaloid isolated from red alga, inhibits lipid peroxidation. Chem. Pharm. Bull 1998, 46, 1527–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nishida, A.; Fuwa, M.; Fujikawa, Y.; Nakahata, E.; Furuno, A.; Nakagawa, M. First total synthesis of martefragin A, a potent inhibitor of lipid peroxidation isolated from sea alga. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 5983–5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagatsu, A.; Kajitani, H.; Sakakibara, J. Muscoride A: A new oxazole peptide alkaloid from freshwater cyanobacterium Nostoc muscorum. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 4097–4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, J.C. Total synthesis of (-)-muscoride A: A novel bis-oxazole based alkaloid from the Cyanobacterium Nostoc muscorum. Synthesis 1998, 1998, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coqueron, P.Y.; Didier, C.; Ciufolini, M.A. Iterative oxazole assembly via α-chloroglycinates: Total synthesis of (−)-muscoride A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 1411–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wipf, P.; Venkatraman, S. Total synthesis of (−)-muscoride A. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 6517–6522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio, C.; Pérez-Díaz, J.C.; Martínez, M.C.; Baquero, F. A new family of low molecular weight antibiotics from enterobacteria. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1976, 69, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorgey, P.; Lee, J.; Kördel, J.; Vivas, E.; Warner, P.; Jebaratnam, D.; Kolter, R. Posttranslational modifications in microcin B17 define an additional class of DNA gyrase inhibitor. Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 4519–4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, R.E.; Jolliffe, K.A.; Payne, R.J. Total synthesis of microcin B17 via a fragment condensation approach. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 680–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Videnov, G.; Kaiser, D.; Brooks, M.; Jung, G. Synthesis of the DNA gyrase inhibitor microcin B17, a 43-peptide antibiotic with eight aromatic heterocycles in its backbone. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1996, 35, 1506–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-M.; Milne, J.C.; Madison, L.L.; Kolter, R.; Walsh, C.T. From peptide precursors to oxazole and thiazole-containing peptide antibiotics: Microcin B17 synthase. Science 1996, 274, 1188–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholz, R.; Molohon, K.J.; Nachtigall, J.; Vater, J.; Markley, A.L.; Süssmuth, R.D.; Mitchell, D.A.; Borriss, R. Plantazolicin, a novel microcin B17/streptolysin S-like natural product from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molohon, K.J.; Melby, J.O.; Lee, J.; Evans, B.S.; Dunbar, K.L.; Bumpus, S.B.; Kelleher, N.L.; Mitchell, D.A. Structure determination and interception of biosynthetic intermediates for the plantazolicin class of highly discriminating antibiotics. ACS Chem. Biol. 2011, 6, 1307–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyon, B.; Helaly, S.E.; Scholz, R.; Nachtigall, J.; Vater, J.; Borriss, R.; Süssmuth, R.D. Plantazolicin A and B: Structure elucidation of ribosomally synthesized thiazole/oxazole peptides from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 2996–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, T.; Kurokawa, Y.; Hayashi, S.; Oku, N.; Asamizu, S.; Igarashi, Y.; Onaka, H. Insights into the biosynthesis of dehydroalanines in goadsporin. ChemBioChem 2016, 17, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaka, H.; Tabata, H.; Igarashi, Y.; Sato, Y.; Furumai, T. Goadsporin, a chemical substance which promotes secondary metabolism and morphogenesis in streptomycetes. J. Antibiot. 2001, 54, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perez, L.J.; Faulkner, D.J. Bistratamides E− J, Modified cyclic hexapeptides from the Philippines Ascidian Lissoclinum bistratum. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urda, C.; Fernández, R.; Rodríguez, J.; Pérez, M.; Jiménez, C.; Cuevas, C. Bistratamides M and N, oxazole-thiazole containing cyclic hexapeptides isolated from Lissoclinum bistratum interaction of zinc (II) with bistratamide K. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foster, M.P.; Concepcion, G.P.; Caraan, G.B.; Ireland, C.M. Bistratamides C and D. Two new oxazole-containing cyclic hexapeptides isolated from a Philippine Lissoclinum bistratum ascidian. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 6671–6675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsep, M.R.; Moore, R.E.; Levine, I.A.; Patterson, G.M. Westiellamide, a bistratamide-related cyclic peptide from the blue-green alga Westiellopsis prolifica. J. Nat. Prod. 1992, 55, 140–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogino, J.; Moore, R.E.; Patterson, G.M.; Smith, C.D. Dendroamides, new cyclic hexapeptides from a blue-green alga. Multidrug-resistance reversing activity of dendroamide A. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 59, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Z.; Smith, C.D. Total synthesis of dendroamide A, a novel cyclic peptide that reverses multiple drug resistance. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 3459–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertram, A.; Pattenden, G. Dendroamide A, nostocyclamide and related cyclopeptides from cyanobacteria. Total synthesis, together with organised and metal-templated assembly from oxazole and thiazole-based amino acids. Heterocycles 2002, 58, 521–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, A.; Pattenden, G. Self-assembly of amino acid-based thiazoles and oxazoles. Total synthesis of dendroamide A, a cyclic hexapeptide from the cyanobacterium Stigonema dendroideum. Synlett 2000, 2000, 1519–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jüttner, F.; Todorova, A.K.; Walch, N.; von Philipsborn, W. Nostocyclamide M: A cyanobacterial cyclic peptide with allelopathic activity from Nostoc 31. Phytochemistry 2001, 57, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.; Carmeli, S. Tenuecyclamides A− D, Cyclic Hexapeptides from the Cyanobacterium Nostoc spongiaeforme var. tenue. J. Nat. Prod. 1998, 61, 1248–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojika, M.; Nemoto, T.; Nakamura, M.; Yamada, K. Dolastatin E, a new cyclic hexapeptide isolated from the sea hare Dolabella auricularia. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 5057–5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sone, H.; Kigoshi, H.; Yamada, K. Isolation and stereostructure of dolastatin I, a cytotoxic cyclic hexapeptide from the Japanese sea hare Dolabella auricularia. Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 8149–8154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Shibata, T.; Nakane, K.; Nemoto, T.; Ojika, M.; Yamada, K. Stereochemistry and total synthesis of dolastatin E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 5059–5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admi, V.; Afek, U.; Carmeli, S. Raocyclamides A and B, novel cyclic hexapeptides isolated from the cyanobacterium Oscillatoria raoi. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 59, 396–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.J.; Pattenden, G. Total synthesis and assignment of stereochemistry of raocyclamide cyclopeptides from cyanobacterium Oscillatoria raoi. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 3251–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, K.; Nakagawa, H.; Murakami, M. Microcyclamide, a Cytotoxic Cyclic Hexapeptide from the Cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1315–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziemert, N.; Ishida, K.; Quillardet, P.; Bouchier, C.; Hertweck, C.; de Marsac, N.T.; Dittmann, E. Microcyclamide biosynthesis in two strains of Microcystis aeruginosa: From structure to genes and vice versa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 1791–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Portmann, C.; Blom, J.F.; Gademann, K.; Jüttner, F. Aerucyclamides A and B: Isolation and synthesis of toxic ribosomal heterocyclic peptides from the cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 1193–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.-L.; Yao, D.-Y.; Gu, M.; Fan, M.-Z.; Li, J.-Y.; Xing, Y.-C.; Nan, F.-J. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel bisheterocycle-containing compounds as potential anti-influenza virus agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 5284–5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohda, K.-Y.; Hiramoto, M.; Suzumura, K.-I.; Takebayashi, Y.; Suzuki, K.-I.; Tanaka, A. YM-216391, a novel cytotoxic cyclic peptide from Streptomyces nobilis. J. Antibiot. 2005, 58, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matsuo, Y.; Kanoh, K.; Yamori, T.; Kasai, H.; Katsuta, A.; Adachi, K.; Shin-Ya, K.; Shizuri, Y. Urukthapelstatin A, a novel cytotoxic substance from marine-derived Mechercharimyces asporophorigenens YM11-542. J. Antibiot. 2007, 60, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kanoh, K.; Matsuo, Y.; Adachi, K.; Imagawa, H.; Nishizawa, M.; Shizuri, Y. Mechercharmycins A and B, cytotoxic substances from marine-derived Thermoactinomyces sp. YM3-251. J. Antibiot. 2005, 58, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernández, D.; Vilar, G.; Riego, E.; Canedo, L.M.; Cuevas, C.; Albericio, F.; Álvarez, M. Synthesis of IB-01211, a cyclic peptide containing 2, 4-concatenated thia-and oxazoles, via Hantzsch macrocyclization. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 809–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rue, E.L.; Bruland, K.W. Complexation of iron (III) by natural organic ligands in the Central North Pacific as determined by a new competitive ligand equilibration/adsorptive cathodic stripping voltammetric method. Mar. Chem. 1995, 50, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Luther, G.W., III. Complexation of Fe (III) by natural organic ligands in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean by a competitive ligand equilibration method and a kinetic approach. Mar. Chem. 1995, 50, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witter, A.E.; Luther, G.W., III. Variation in Fe-organic complexation with depth in the Northwestern Atlantic Ocean as determined using a kinetic approach. Mar. Chem. 1998, 62, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, N.M.; Morel, F.M. Biological cycling of iron in the ocean. In Metal Ions in Biological Systems; Sigel, A., Sigel, H., Eds.; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 35, pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, L.L.; Sera, Y.; Adachi, K.; Nishida, F.; Shizuri, Y. Isolation and evaluation of nonsiderophore cyclic peptides from marine sponges. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 283, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sera, Y.; Adachi, K.; Fujii, K.; Shizuri, Y. Isolation of Haliclonamides: New peptides as antifouling substances from a marine sponge species. Haliclona. Mar. Biotechnol. 2002, 4, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Miki, W. A newly developed bioassay system for antifouling substances using the blue mussel, Mytilus edulis galloprovincialis. J. Mar. Biotechnol. 1996, 4, 127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, K.L.; Gustafson, K.R.; Milanowski, D.J.; Pannell, L.K.; Klose, J.R.; Boyd, M.R. Myriastramides A–C, new modified cyclic peptides from the Philippines marine sponge Myriastra clavosa. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 10231–10238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogle, L.M.; Marquez, B.L.; Gerwick, W.H. Wewakazole, a novel cyclic dodecapeptide from a Papua New Guinea Lyngbya majuscula. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, B.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Tang, X.; Wu, Z. Total synthesis and biological evaluation of Wewakazole. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2017, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloy, K.L.; Villa, F.A.; Engene, N.; Matainaho, T.; Gerwick, L.; Gerwick, W.H. Malyngamide 2, an oxidized lipopeptide with nitric oxide inhibiting activity from a Papua New Guinea marine cyanobacterium. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kobayashi, J.; Itagaki, F.; Shigemori, H.; Ishibashi, M.; Takahashi, K.; Ogura, M.; Nagasawa, S.; Nakamura, T.; Hirota, H. Keramamides B. apprx. D, novel peptides from the Okinawan marine sponge Theonella sp. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 7812–7813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, J.I.; Itagaki, F.; Shigemori, I.; Takao, T.; Shimonishi, Y. Keramamides E, G, H, and J, new cyclic peptides containing an oxazole or a thiazole ring from a Theonella sponge. Tetrahedron 1995, 51, 2525–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, J.I.; Sato, M.; Ishibashi, M.; Shigemori, H.; Nakamura, T.; Ohizumi, Y. Keramamide A, a novel peptide from the Okinawan marine sponge Theonella sp. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1991, 1, 2609–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, R.; Martin, M.J.; Rodríguez-Acebes, R.; Reyes, F.; Francesch, A.; Cuevas, C. Diazonamides C–E, new cytotoxic metabolites from the ascidian Diazona sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 2283–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindquist, N.; Fenical, W.; Van Duyne, G.D.; Clardy, J. Isolation and structure determination of diazonamides A and B, unusual cytotoxic metabolites from the marine ascidian Diazona chinensis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 2303–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just-Baringo, X.; Bruno, P.; Pitart, C.; Vila, J.; Albericio, F.; Álvarez, M. Dissecting the structure of thiopeptides: Assessment of thiazoline and tail moieties of baringolin and antibacterial activity optimization. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 4185–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just-Baringo, X.; Bruno, P.; Ottesen, L.K.; Cañedo, L.M.; Albericio, F.; Álvarez, M. Total synthesis and stereochemical assignment of baringolin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 7818–7821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagley, M.C.; Dale, J.W.; Merritt, E.A.; Xiong, X. Thiopeptide antibiotics. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 685–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, B.-S.; Hidaka, T.; Furihata, K.; Seto, H. Promothiocins A and B, novel thiopeptides with a tip A promoter inducing activity produced by Streptomyces sp. SF2741. J. Antibiot. 1994, 47, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matsumoto, M.; Kawamura, Y.; Yasuda, Y.; Tanimoto, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Yoshida, T.; Shoji, J.I. Isolation and characterization of thioxamycin. J. Antibiot. 1989, 42, 1465–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yun, B.-S.; Hidaka, T.; Furihata, K.; Seto, H. Microbial metabolites with tipA promoter inducing activity. III. Thioxamycin and its novel derivative, thioactin, two thiopeptides produced by Streptomyces sp. DP94. J. Antibiot. 1994, 47, 1541–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murakami, T.; Holt, T.; Thompson, C. Thiostrepton-induced gene expression in Streptomyces lividans. J. Bacteriol. 1989, 171, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, B.; Hodgkin, D.C.; Viswamitra, M. The structure of thiostrepton. Nature 1970, 225, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, D.; Caso, J.; Thompson, C. Autogenous transcriptional activation of a thiostrepton-induced gene in Streptomyces lividans. EMBO J. 1993, 12, 3183–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, B.-S.; Fujita, K.-I.; Furihata, K.; Seto, H. Absolute stereochemistry and solution conformation of promothiocins. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 9683–9687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egawa, Y.; Umino, K.; Tamura, Y.; Shimizu, M.; Kaneko, K.; Sakurazawa, M.; Awataguchi, S.; Okuda, T. Sulfomycins, a series of new sulfur-containing antibiotics. I. J. Antibiot. 1969, 22, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohno, J.; Kameda, N.; Nishio, M.; Kinumaki, A.; Komaatsubara, S. The structures of sulfomycins II and III. J. Antibiot. 1996, 49, 1063–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abe, H.; Kushida, K.; Shiobara, Y.; Kodama, M. The structures of sulfomycin I and berninamycin A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 1401–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, L.A.; Rickes, E.L.; Duquette, P.F.; Smith, G.E. Prevention of induced lactic acidosis in cattle by thiopeptin. J. Anim. Sci. 1981, 52, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debono, M.; Molloy, R.M.; Occolowitz, J.L.; Paschal, J.W.; Hunt, A.H.; Michel, K.H.; Martin, J.W. The structures of A10255 B,-G and-J: New thiopeptide antibiotics produced by Streptomyces gardneri. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 5200–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favret, M.E.; Boeck, L.V.D. Effect of cobalt and cyano-cobalamin on biosynthesis of A10255, a thiopeptide antibiotic complex. J. Antibiot. 1992, 45, 1809–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vijaya Kumar, E.; Kenia, J.; Mukhopadhyay, T.; Nadkarni, S. Methylsulfomycin I, a new cyclic peptide antibiotic from a Streptomyces sp. HIL Y-9420704. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 1562–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Peptide Name | Natural Source | Organism | Bioactivity | Class/Type | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A10225B, G and E | Colorado soil bacterium | Streptomyces gardneri NRRL 15537 | Antimicrobial activity, growth promoter, prevent lactic acidosis in farm animals | Thiopeptides | [92,93] |

| Aerucyclamides C | Cyanobacterium | Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806 | Promising antimalarial agent | Cyclic peptide | [56] |

| Almazoles A–D | Senegal seaweed | Genus Haraldiophyllum | Almazole D: antibacterial activity | Short linear peptide | [18,19,20,21,22] |

| Baringolin | Spain bacterium | Kucuria sp. MI-67-EC3-038 | Antibacterial activity | Thiopeptide | [78,79] |

| Bistratamides | Philippine ascidian | Lissoclinum bistratum | Bistratamide D: neurodepressant properties Bistratamides M and N: with antitumor activity | Cyclic peptides | [39,40,41] |

| Dendroamides A–C | Terrestrial blue-green alga | Stigonema dendroideum | Dendroamide A: potent MDR-reversing agent | Cyclic peptide | [43,44,45] |

| Diazonamides A–E | Marine colonial ascidian | Diazona angulata | Cytotoxicity activity | Bicyclic peptide | [76,77] |

| Dolastatins E and I | Japanese sea hare | Dolabella auricularia | Cytotoxicity activity | Cyclic hexapeptides | [49,51] |

| Goadsporin | Soil bacterium | Streptomyces sp. TP-A0584 | Antibacterial activity | Long linear peptide | [37,38] |

| Haliclonamides A–E | Palauan marine sponge | Haliclona sp. | Haliclona A and B: Metal-Iron uptake Haliclonamide C–E: antifouling activity | Cyclic peptides | [62,63,64,65,66,67] |

| Keramamides | Okinawan marine sponge | Theonella sp. | Keramamide B–D: inhibits superoxides Keramamide E: antitumor activity | Cyclic peptides | [73,74,75] |

| Leucamide A | Australian marine sponge | Leucetta microraphis | Cytotoxicity activity | Cyclic peptide | [10,57] |

| Martefragin A | Marine Red algae | Martensia fragilis | Inhibit lipid peroxidation | Short linear peptides | [23,24] |

| Mechercharmycins A and B | Marine bacterium | Thermoactinomyces sp. YM3-251 | Mechercharmycins A: antitumor activity | Cyclic peptides | [60] |

| Methylsulfomycin I | Soil bacterium | Streptomyces sp. HIL Y-9420704 | Antibacterial activity | Thiopeptide | [94] |

| Microcyclamides 7806 A and B | Cyanobacterium | Microcystis aeruginosa NIES-298 and PCC-7806 | Microcyclamide: Cytotoxicity activity | Cyclic peptides | [54,55] |

| Microcin B17 | Soil bacterium | Escherichia coli | Poison DNA gyrase | Long linear peptide | [29,30,31,32,33,34] |

| Muscoride A | Cyanobacterium | Nostoc muscorum | Antibacterial activity | Short linear peptide | [25,26,27,28] |

| Myriastramides | Cyanobacterium | Myriastra clavosa | No biological activity mentioned on literature | Cyclic peptides | [69] |

| Nostocyclamide, Nostocyclamide M | Cyanobacterium | Nostoc 31 | Both have cyanobacterial and allelopathic activity Nostocyclamide M: anti-algal activity | Cyclic peptides | [12,47] |

| Plantazolicins A and B | Soil bacterium | Bacillus amyloliquifaciens FZB42 | Plantazolicin A: Antibacterial activity | Long linear peptides | [34,35,36] |

| Promothiocins A and B | Soil bacterium | Streptomyces sp. SF2741 | Not reported in literature | Thiopeptide | [81,87] |

| Raocyclamides A and B | Cyanobacterium | Oscillatoria raoi | Raocyclamide A: Cytotoxicity activity | Cyclic peptide | [52,53] |

| Sulfomycins I-III | Soil bacterium | Streptomyces viridochromogenes MCRL-0368 | Antibacterial activity | Thiopeptide | [88,89,90] |

| Tenuecyclamides A–D | Cyanobacterium | Nostoc spongiaeforme var. tenue Rao | Antimicrobial and cytotoxicity activity | Cyclic peptides | [48] |

| Thioxamycin and Thioactin | Soil bacterium | Streptomyces sp. strain PA-46025 | Antibacterial activity | Thiopeptide | [82,83] |

| Urukthapelstatin A | Marine bacterium | Mechercharimyces asporophorigenens YM11-542 | Cytotoxicity activity | Cyclic peptide | [59] |

| Venturamides A and B | Cyanobacterium | Oscillatoria sp. | Antimalarial activity | Cyclic peptides | [11] |

| Wewakazole A and B | Cyanobacterium | Lyngbya majuscula, Moorea producens | Cytotoxicity activity | Cyclic peptides | [13,71,72] |

| YM-216391 | Soil bacterium | Streptomyces nobilis | Cytotoxicity activity | Cyclic peptide | [58] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mhlongo, J.T.; Brasil, E.; de la Torre, B.G.; Albericio, F. Naturally Occurring Oxazole-Containing Peptides. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/md18040203

Mhlongo JT, Brasil E, de la Torre BG, Albericio F. Naturally Occurring Oxazole-Containing Peptides. Marine Drugs. 2020; 18(4):203. https://doi.org/10.3390/md18040203

Chicago/Turabian StyleMhlongo, Jessica T., Edikarlos Brasil, Beatriz G. de la Torre, and Fernando Albericio. 2020. "Naturally Occurring Oxazole-Containing Peptides" Marine Drugs 18, no. 4: 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/md18040203

APA StyleMhlongo, J. T., Brasil, E., de la Torre, B. G., & Albericio, F. (2020). Naturally Occurring Oxazole-Containing Peptides. Marine Drugs, 18(4), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/md18040203