Possible Functional Roles of Patellamides in the Ascidian-Prochloron Symbiosis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Discovery of Prochloron and the Ascidian-Prochloron Symbiosis

2. Isolation, Synthesis, Molecular and Biological Properties of Patellamides and Their Metal Complexes

2.1. Medical Applications and Structures of Metal-Free Patellamides

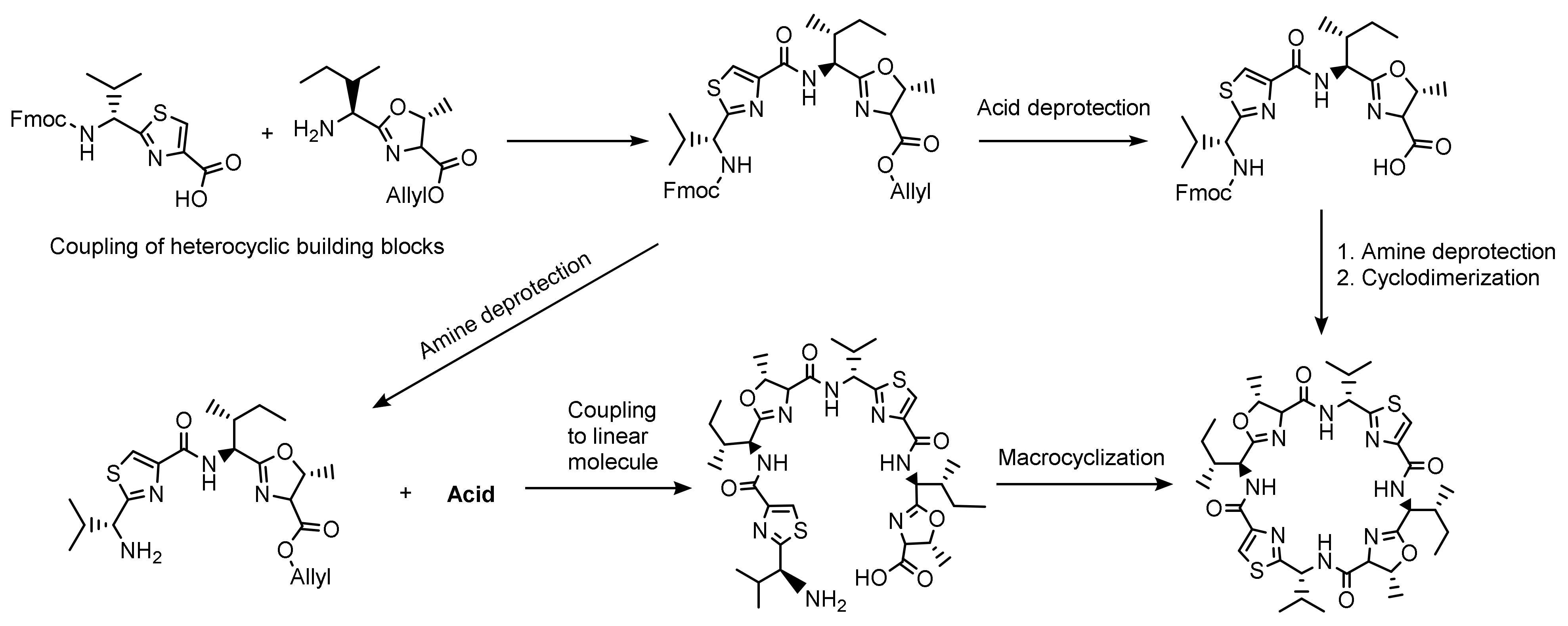

2.2. Patellamide Syntheses

2.3. Structural Properties of Patellamide Complexes

2.4. Catalytic Properties of Patellamide Complexes

3. The Symbiotic Backdrop—A Highly Dynamic Place of Patellamide Production

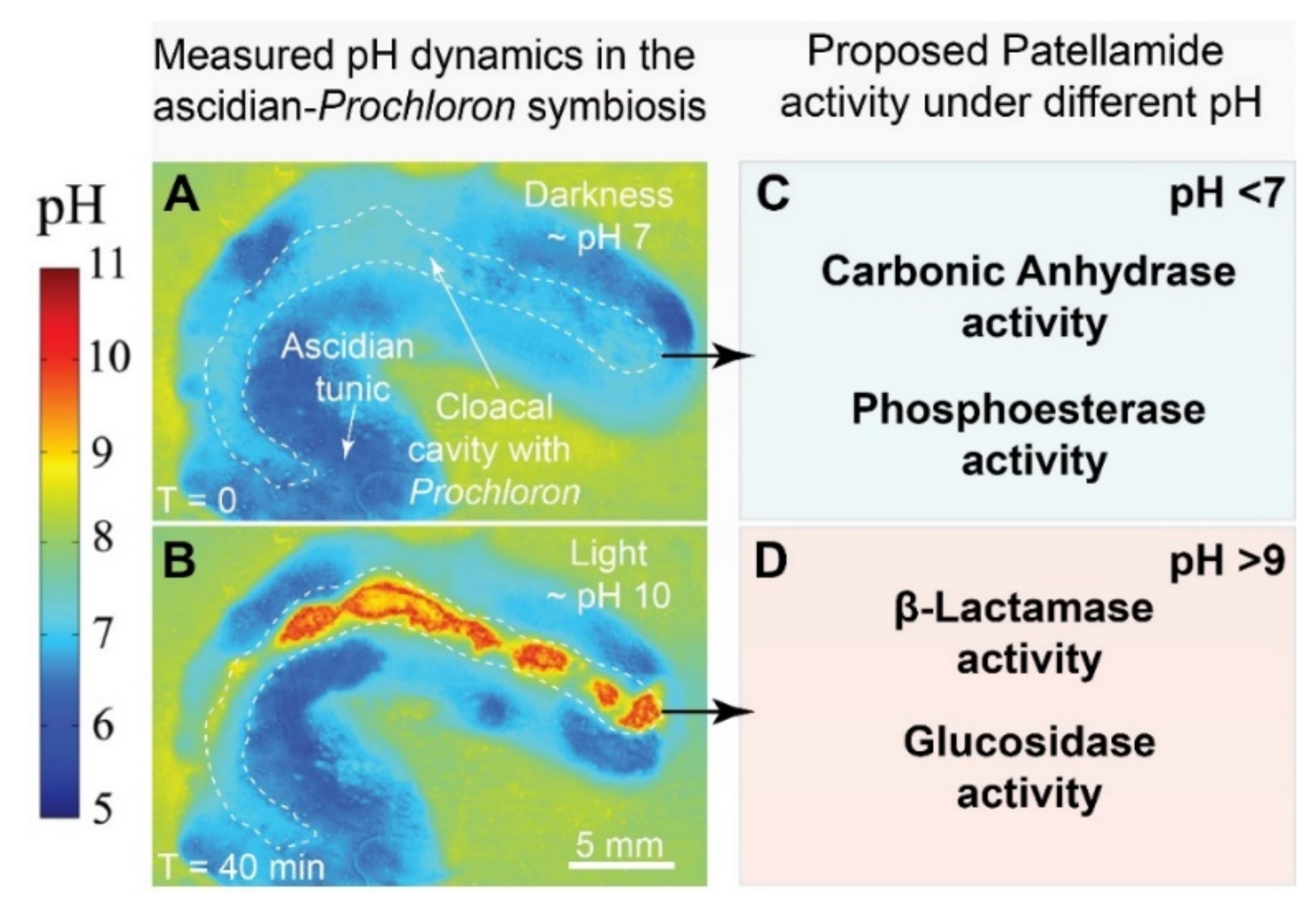

3.1. Microenvironments and Biological Dynamics of the Ascidian-Prochloron Symbiosis

3.1.1. The Outer Surface and Tunic of Ascidians

3.1.2. The Cloacal Cavity of Ascidians

3.1.3. The Underside of Ascidians

3.2. Possible Functions of Patellamides in the Ascidian-Prochloron Symbiosis

3.2.1. Metal Ion Sequestration and Transport

3.2.2. Protection

3.2.3. Catalysis and Transport of Substrates

4. Summary and the Future of Patellamide Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lewin, R.A.; Cheng, L. (Eds.) Prochloron: A Microbial Enigma; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-1-4612-8203-7. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, G. Comparison of Prochloron from different hosts. I. Structural and ultrastructural characteristics. New Phytol. 1986, 104, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, E. Ascidian photosymbiosis: Diversity of cyanobacterial transmission during embryogenesis. Genesis 2015, 53, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, D.A.; Pernice, M.; Schliep, M.; Sablok, G.; Jeffries, T.C.; Kühl, M.; Wangpraseurt, D.; Ralph, P.J.; Larkum, A.W.D. Microenvironment and phylogenetic diversity of Prochloron inhabiting the surface of crustose didemnid ascidians. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 4121–4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurice, C. Etude Monographique d’Une Espece d’Ascidies Composee; Liege, Belgium, 1888; Volume 8. Available online: https://books.google.com.hk/books?id=1qoMAQAAIAAJ&ots=wXc2zsas1U&dq=Etude%20Monographique%20d%E2%80%99une%20Espece%20d%E2%80%99Ascidies%20Composee&lr&hl=zh-CN&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Smith, H.G. LXI.—On the presence of algæ in certain Ascidiacea. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 1935, 15, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokioka, T. Ascidians found on the mangrove trees in Lwayama Bay, Palau. Palau Trop. Biol. Station Stud. 1942, 2, 499–507. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, R.A. Prochloron, type genus of the Prochlorophyta. Phycologia 1977, 16, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, R.A.; Cheng, L. Associations of microscopic algae with didemnid ascidians. Phycologia 1975, 14, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcomb, E.H.; Pugh, T.D. Blue-green algae associated with ascidians of the Great Barrier Reef. Nature 1975, 253, 533–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, R.A.; Withers, N.W. Extraordinary pigment composition of a prokaryotic alga. Nature 1975, 256, 735–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, R.A. Prochloron—A status report. Phycologia 1984, 23, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S. Molecular systematics of oxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. In Origins of Algae and Their Plastids; Bhattacharya, D., Ed.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1997; pp. 13–52. [Google Scholar]

- Roche, J.L.; van der Staay, G.W.M.; Partensky, F.; Ducret, A.; Aebersold, R.; Li, R.; Golden, S.S.; Hiller, R.G.; Wrench, P.M.; Larkum, A.W.D.; et al. Independent evolution of the prochlorophyte and green plant chlorophyll a/b light-harvesting proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 15244–15248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rumengan, I.F.M.; Kubelaborbir, T.M.; Tallei, T.E. Data on the cultivation of Prochloron sp. at different salinity levels. Data Brief 2020, 29, 105241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumengan, I.F.M.; Roring, V.I.Y.; Haedar, J.R.; Siby, M.S.; Luntungan, A.H.; Kolondam, B.J.; Uria, A.R.; Wakimoto, T. Ascidian-associated photosymbionts from Manado, Indonesia: Secondary metabolites, bioactivity simulation, and biosynthetic insight. Symbiosis 2021, 84, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, E.; Nozawa, Y. Latitudinal difference in the species richness of photosymbiotic ascidians along the east coast of Taiwan. Zool. Stud. 2020, 59, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.R. Light-enhanced growth of the ascidian Didemnum molle/Prochloron sp. symbiosis. Mar. Biol. 1986, 93, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, B.P.; Pardy, R.; Lewin, R.A. Carbon fixation and photosynthates of Prochloron, a green alga symbiotic with an ascidian, Lissoclinum patella. Phycologia 1982, 21, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, I.; Yamamuro, M.; Pollard, P. Carbon and nitrogen budgets of two ascidians and their symbiont, Prochloron, in a tropical seagrass meadow. Aust. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1993, 44, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, I.; Suzuki, T. Nutritional diversity of symbiotic ascidians in a Fijian seagrass meadow. Ecol. Res. 1996, 11, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, E.W.; Donia, M.S.; McIntosh, J.A.; Fricke, W.F.; Ravel, J. Origin and variation of tunicate secondary metabolites. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Comba, P.; Dovalil, N.; Gahan, L.R.; Hanson, G.R.; Westphal, M. Cyclic peptide marine metabolites and CuII. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 1935–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Comba, P.; Eisenschmidt, A. Structures, electronics and reactivity of copper(II) complexes of the cyclic pseudo-peptides of the ascidians. In Future Directions in Metalloprotein and Metalloenzyme Research; Hanson, G., Berliner, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 13–32. ISBN 978-3-319-59100-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gahan, L.R.; Cusack, R.M. Metal complexes of synthetic cyclic peptides. Polyhedron 2018, 153, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspars, M.; De Pascale, D.; Andersen, J.H.; Reyes, F.; Crawford, A.D.; Ianora, A. The marine biodiscovery pipeline and ocean medicines of tomorrow. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2016, 96, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ireland, C.M.; Durso, A.R.; Newman, R.A.; Hacker, M.P. Antineoplastic cyclic peptides from the marine tunicate Lissoclinum patella. J. Org. Chem. 1982, 47, 1807–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, C.E.; Faulkner, D.J. Localization studies of bioactive cyclic peptides in the ascidian Lissoclinum patella. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 689–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, E.W.; Donia, M.S. Life in cellulose houses: Symbiotic bacterial biosynthesis of ascidian drugs and drug leads. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010, 21, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Behrendt, L.; Raina, J.-B.; Lutz, A.; Kot, W.; Albertsen, M.; Halkjær-Nielsen, P.; Sørensen, S.J.; Larkum, A.W.; Kühl, M. In situ metabolomic- and transcriptomic-profiling of the host-associated cyanobacteria Prochloron and Acaryochloris marina. ISME J. 2018, 12, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, E.; Nelson, J.; Rasko, D.; Sudek, S.; Eisen, J.; Haygood, M.; Ravel, J. Patellamide A and C biosynthesis by a microcin-like pathway in Prochloron didemni, the cyanobacterial symbiont of Lissoclinum patella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 7315–7320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lopanik, N.B. Chemical defensive symbioses in the marine environment. Funct. Ecol. 2014, 28, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, J.C.; Donia, M.S.; Han, A.W.; Hirose, E.; Haygood, M.G.; Schmidt, E.W. Genome streamlining and chemical defense in a coral reef symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 20655–20660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andavan, G.S.B.; Lemmens-Gruber, R. Cyclodepsipeptides from marine sponges: Natural agents for drug research. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 810–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stonik, V.; Fedorov, S. Marine low molecular weight natural products as potential cancer preventive compounds. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 636–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.T. Pharmaceutical agents from filamentous marine cyanobacteria. Drug Discov. Today 2013, 18, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.T. Bioactive natural products from marine cyanobacteria for drug discovery. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 954–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, B.; Lin, X.; Yang, X.-W.; Liu, Y. Marine natural products with anti-HIV activities in the last decade. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 953–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. The potential biomedical application of cyclopeptides from marine natural products. Curr. Org. Chem. 2014, 18, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, D.; Davis, R.A.; Evans-Illidge, E.A.; Quinn, R.J. Guiding principles for natural product drug discovery. Future Med. Chem. 2012, 4, 1067–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Vries, D.J.; Beart, P.M. Fishing for drugs from the sea: Status and strategies. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1995, 16, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiuru, P.; D’Auria, M.; Muller, C.; Tammela, P.; Vuorela, H.; Yli-Kauhaluoma, J. Exploring marine resources for bioactive compounds. Planta Med. 2014, 80, 1234–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinski, T.F.; Dalisay, D.S.; Lievens, S.L.; Saludes, J.P. Drug development from marine natural products. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009, 8, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Reyes, L.A.; Luesch, H. Biological targets and mechanisms of action of natural products from marine cyanobacteria. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 478–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Degnan, B.M.; Hawkins, C.J.; Lavin, M.F.; McCaffrey, E.J.; Parry, D.L.; Van den Brenk, A.L.; Watters, D.J. New cyclic peptides with cytotoxic activity from the ascidian Lissoclinum patella. J. Med. Chem. 1989, 32, 1349–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, C.J.; Lavin, M.F.; Marshall, K.A.; Van den Brenk, A.L.; Watters, D.J. Structure-activity relationships of the lissoclinamides: Cytotoxic cyclic peptides from the ascidian Lissoclinum patella. J. Med. Chem. 1990, 33, 1634–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, L.A.; Ireland, C.M. Patellamide E: A new cyclic peptide from the ascidian Lissoclinum patella. J. Nat. Prod. 1992, 55, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, F.J.; Ksebati, M.B.; Chang, J.S.; Wang, J.L.; Hossain, M.B.; Van der Helm, D.; Engel, M.H.; Serban, A.; Silfer, J.A. Cyclic peptides from the ascidian Lissoclinum patella: Conformational analysis of patellamide D by X-ray analysis and molecular modeling. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 3463–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.A.; Gustafson, K.R.; Cardeilina, J.H.; Boyd, M.R. Mycalolides D and E, New cytotoxic macrolides from a collection of the stony coral Tubastrea faulkneri. J. Nat. Prod. 1995, 58, 1120–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A.B.; Jacobs, R.S. A marine natural product, patellamide D, reverses multidrug resistance in a human leukemic cell line. Cancer Lett. 1993, 71, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-Reyes, L.A.; Engene, N.; Paul, V.J.; Luesch, H. Targeted natural products discovery from marine cyanobacteria using combined phylogenetic and mass spectrometric evaluation. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hughes, R.A.; Moody, C.J. From amino acids to heteroaromatics—thiopeptide antibiotics, nature’s heterocyclic peptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 7930–7954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just-Baringo, X.; Bruno, P.; Ottesen, L.K.; Cañedo, L.M.; Albericio, F.; Álvarez, M. Total synthesis and stereochemical assignment of baringolin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 7818–7821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.S.; Robertson, A.A.B.; Cooper, M.A. Natural product and natural product derived drugs in clinical trials. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 1612–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyshlovoy, S.; Honecker, F. Marine compounds and cancer: Where do we stand? Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5657–5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, Y.; Kato, S.; Shioiri, T. New methods and reagents in organic synthesis. 51. A synthesis of ascidiacyclamide, a cytotoxic cyclic peptide from ascidian—Determination of its absolute configuration. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 3223–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, P.; Comba, P.; Velmurugan, G. Efficient synthesis for a wide variety of patellamide derivatives and phosphatase activity of copper-patellamide complexes. Chem. Eur. J. 2022. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Koehnke, J.; Bent, A.F.; Houssen, W.E.; Mann, G.; Jaspars, M.; Naismith, J.H. The structural biology of patellamide biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2014, 29, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García-Reynaga, P.; VanNieuwenhze, M.S. A new total synthesis of patellamide A. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 4621–4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Comba, P.; Dovalil, N.; Gahan, L.R.; Haberhauer, G.; Hanson, G.R.; Noble, C.J.; Seibold, B.; Vadivelu, P. CuII coordination chemistry of patellamide derivatives: Possible biological functions of cyclic pseudopeptides. Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 2578–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberhauer, G.; Oeser, T.; Rominger, F. A widely applicable concept for predictable induction of preferred configuration in C3-symmetric systems. Chem. Commun. 2005, 2799–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberhauer, G.; Pintér, Á.; Oeser, T.; Rominger, F. Synthesis and Structural Investigation of C4- and C2-Symmetric Molecular Scaffolds Based on Imidazole Peptides. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 2007, 1779–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberhauer, G.; Drosdow, E.; Oeser, T.; Rominger, F. Structural investigation of westiellamide analogues. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 1853–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Savchenko, A.I.; Krenske, E.H.; Grange, R.L.; Gahan, L.R.; Williams, C.M. Developing cyclic peptide heteroatom interchange: Synthesis and DFT modelling of a HI-ascidiacyclamide isomer. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 2018, 3265–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbenante, G.; Fairlie, D.P.; Gahan, L.R.; Hanson, G.R.; Pierens, G.K.; van den Brenk, A.L. Conformational control by thiazole and oxazoline rings in cyclic octapeptides of marine origin. Novel macrocyclic chair and boat conformations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 10384–10388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; In, Y.; Shinozaki, F.; Doi, M.; Yamamoto, D.; Hamada, Y.; Shioiri, T.; Kamigauchi, M.; Sugiura, M. Solution conformations of patellamides B and C, cytotoxic cyclic hexapeptides from marine tunicate, determined by NMR spectroscopy and molecular dynamics. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 3944–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; In, Y.; Doi, M.; Inoue, M.; Hamada, Y.; Shiori, T. Molecular conformation of ascidiacyclamide, a cytotoxic cyclic peptide from Ascidian: X-ray analyses of its free form and solvate crystals. Biopolymers 1992, 32, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- In, Y.; Doi, M.; Inoue, M.; Ishida, T.; Hamada, Y.; Shioiri, T. Molecular conformation of patellamide A, a cytotoxic cyclic peptide from the ascidian Lissoclinum patella, by x-ray crystal analysis. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1993, 41, 1686–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- In, Y.; Doi, M.; Inoue, M.; Ishida, T.; Hamada, Y.; Shioiri, T. Patellamide A, a cytotoxic cyclic peptide from the ascidian Lissoclinum patella. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Cryst. Struct. Commun. 1994, 50, 432–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, R.M.; Grøndahl, L.; Abbenante, G.; Fairlie, D.P.; Gahan, L.R.; Hanson, G.R.; Hambley, T.W. Conformations of cyclic octapeptides and the influence of heterocyclic ring constraints upon calcium binding. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 2000, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, B.F.; Morris, L.A.; Jaspars, M.; Thompson, G.S. Conformational change in the thiazole and oxazoline containing cyclic octapeptides, the patellamides. Part 2. Solvent dependent conformational change. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 2002, 1076–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberhauer, G.; Rominger, F. Synthesis of a new class of imidazole-based cyclic peptides. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 6335–6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintér, Á.; Haberhauer, G. Synthesis of chiral threefold and sixfold functionalized macrocyclic imidazole peptides. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 2217–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Inoue, M.; Hamada, Y.; Kato, S.; Shioiri, T. X-ray crystal structure of ascidiacyclamide, a cytotoxic cyclic peptide from ascidian. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1987, 370–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, M.; Nakagawa, M.; Hamamoto, Y.; Nakanishi, Y. Calvularins, a new class of cytotoxic compounds isolated from the soft coral, Clavularia koellikeri. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1983, 322–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comba, P.; Dovalil, N.; Hanson, G.R.; Linti, G. Synthesis and Cu II coordination chemistry of a patellamide derivative: Consequences of the change from the natural thiazole/oxazoline to the artificial imidazole heterocycles. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 5165–5174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comba, P.; Dovalil, N.; Haberhauer, G.; Kowski, K.; Mehrkens, N.; Westphal, M. Copper solution chemistry of cyclic pseudo-octapeptides. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2013, 639, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brenk, A.L.; Fairlie, D.P.; Hanson, G.R.; Gahan, L.R.; Hawkins, C.J.; Jones, A. Binding of copper(II) to the cyclic octapeptide patellamide D. Inorg. Chem. 1994, 33, 2280–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donia, M.S.; Hathaway, B.J.; Sudek, S.; Haygood, M.G.; Rosovitz, M.J.; Ravel, J.; Schmidt, E.W. Natural combinatorial peptide libraries in cyanobacterial symbionts of marine ascidians. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006, 2, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oueis, E.; Nardone, B.; Jaspars, M.; Westwood, N.J.; Naismith, J.H. Synthesis of hybrid cyclopeptides through enzymatic macrocyclization. ChemistryOpen 2017, 6, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koehnke, J.; Bent, A.F.; Zollman, D.; Smith, K.; Houssen, W.E.; Zhu, X.; Mann, G.; Lebl, T.; Scharff, R.; Shirran, S.; et al. The cyanobactin heterocyclase enzyme: A processive adenylase that operates with a defined order of reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 13991–13996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Houssen, W.E.; Bent, A.F.; McEwan, A.R.; Pieiller, N.; Tabudravu, J.; Koehnke, J.; Mann, G.; Adaba, R.I.; Thomas, L.; Hawas, U.W.; et al. An efficient method for the in vitro production of azol(in)e-based cyclic peptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 14171–14174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oueis, E.; Jaspars, M.; Westwood, N.J.; Naismith, J.H. Enzymatic macrocyclization of 1,2,3-triazole peptide mimetics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 5842–5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oueis, E.; Stevenson, H.; Jaspars, M.; Westwood, N.J.; Naismith, J.H. Bypassing the proline/thiazoline requirement of the macrocyclase PatG. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 12274–12277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alexandru-Crivac, C.N.; Umeobika, C.; Leikoski, N.; Jokela, J.; Rickaby, K.A.; Grilo, A.M.; Sjö, P.; Plowright, A.T.; Idress, M.; Siebs, E.; et al. Cyclic peptide production using a macrocyclase with enhanced substrate promiscuity and relaxed recognition determinants. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 10656–10659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wipf, P. Synthetic studies of biologically active marine cyclopeptides. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 2115–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comba, P.; Cusack, R.; Fairlie, D.P.; Gahan, L.R.; Hanson, G.R.; Kazmaier, U.; Ramlow, A. The solution structure of a copper(II) compound of a new cyclic octapeptide by EPR spectroscopy and force field calculations. Inorg. Chem. 1998, 37, 6721–6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberhauer, G.; Rominger, F. Syntheses and structures of imidazole analogues of Lissoclinum cyclopeptides. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 2003, 3209–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, L.A.; Jaspars, M. A Cu2+ selective marine metabolite. In Biodiversity: New Leads for the Pharmaceutical and Agrochemical Industries; Chrystal, E.J.T., Wrigley, S.K., Thomas, R., Nicholson, N., Hayes, M., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 140–166. ISBN 9781847550231. [Google Scholar]

- Hamada, Y.; Shibata, M.; Shioiri, T. New methods and reagents in organic synthesis. 56. Total syntheses of patellamides B and C, cytotoxic cyclic peptides from a tunicate 2. Their real structures have been determined by their syntheses. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 5159–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.-L.; Kelly, J.W. Total synthesis of dendroamide A: Oxazole and thiazole construction using an oxodiphosphonium salt. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 9506–9509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, L.A.; Jaspars, M.; Kettenes-van den Bosch, J.J.; Versluis, K.; Heck, A.J.; Kelly, S.M.; Price, N.C. Metal binding of Lissoclinum patella metabolites. Part 1: Patellamides A, C and ulithiacyclamide A. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 3185–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, L.A.; Milne, B.F.; Jaspars, M.; Jantina Kettenes-van den Bosch, J.; Versluis, K.; Heck, A.J.; Kelly, S.M.; Price, N.C. Metal binding of Lissoclinum patella metabolites. Part 2: Lissoclinamides 9 and 10. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 3199–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, R.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Milne, B.F.; Jaspars, M.; de Visser, S.P. Density functional theory studies of oxygen and carbonate binding to a dicopper patellamide complex. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2008, 102, 2171–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Comba, P.; Gahan, L.R.; Haberhauer, G.; Hanson, G.R.; Noble, C.J.; Seibold, B.; van den Brenk, A.L. Copper(II) Coordination chemistry of westiellamide and its imidazole, oxazole, and thiazole analogues. Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 4393–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comba, P.; Dovalil, N.; Hanson, G.R.; Harmer, J.R.; Noble, C.J.; Riley, M.J.; Seibold, B. Insights into the electronic structure of CuII bound to an imidazole analogue of westiellamide. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 12323–12336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Comba, P.; Eisenschmidt, A.; Gahan, L.R.; Hanson, G.R.; Mehrkens, N.; Westphal, M. Dinuclear Zn II and mixed CuII –ZnII complexes of artificial patellamides as phosphatase models. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 18931–18945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhardt, P.V.; Comba, P.; Hambley, T.W.; Massoud, S.S.; Stebler, S. Determination of solution structures of binuclear copper(II) complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1992, 31, 2644–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brenk, A.L.; Byriel, K.A.; Fairlie, D.P.; Gahan, L.R.; Hanson, G.R.; Hawkins, C.J.; Jones, A.; Kennard, C.H.L.; Moubaraki, B.; Murray, K.S. Crystal structure and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry, electron paramagnetic resonance, and magnetic susceptibility study of [Cu2(ascidH2)(1,2-µ-CO3)(H2O)2]·2H2O, the bis(copper(II)) complex of ascidiacyclamide (ascidH4), a cyclic peptide isolated from the ascidian Lissoclinum patella. Inorg. Chem. 1994, 33, 3549–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comba, P.; Gahan, L.R.; Hanson, G.R.; Maeder, M.; Westphal, M. Carbonic anhydrase activity of dinuclear Cu II complexes with patellamide model ligands. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 3144–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Comba, P.; Eisenschmidt, A.; Velmurugan, G.; Institute of Inorganic Chemistry, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany. 2022; Manuscript in preparation.

- Comba, P.; Eisenschmidt, A.; Gahan, L.R.; Herten, D.-P.; Nette, G.; Schenk, G.; Seefeld, M. Is CuII coordinated to patellamides inside Prochloron cells? Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 12264–12274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Comba, P.; Gahan, L.R.; Hanson, G.R.; Westphal, M. Phosphatase reactivity of a dicopper(ii) complex of a patellamide derivative—Possible biological functions of cyclic pseudopeptides. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 9364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comba, P.; Eisenschmidt, A.; Kipper, N.; Schießl, J. Glycosidase- and β-lactamase-like activity of dinuclear copper(II) patellamide complexes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2016, 159, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehl, M.A.R.; Powell, T.M.; Dobbins, E.L. Effects of algal turf on mass transport and flow microhabitats of ascidians in a coral reef lagoon. In Proceedings of the 8th International Coral Reef Symposium, Panama City, FL, USA, 24–29 June 1996; pp. 1087–1092. [Google Scholar]

- Kühl, M.; Behrendt, L.; Trampe, E.; Qvortrup, K.; Schreiber, U.; Borisov, S.M.; Klimant, I.; Larkum, A.W.D. Microenvironmental ecology of the chlorophyll b-containing symbiotic cyanobacterium Prochloron in the didemnid ascidian Lissoclinum patella. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kühl, M.; Larkum, A.W.D. The Microenvironment and Photosynthetic Performance of Prochloron sp. in Symbiosis with Didemnid Ascidians. In Symbiosis; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 3, pp. 273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Dionisio-Sese, M.L.; Ishikura, M.; Maruyama, T.; Miyachi, S. UV-absorbing substances in the tunic of a colonial ascidian protect its symbiont, Prochloron sp., from damage by UV-B radiation. Mar. Biol. 1997, 128, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, E.; Ohtsuka, K.; Ishikura, M.; Maruyama, T. Ultraviolet absorption in ascidian tunic and ascidian-Prochloron symbiosis. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2004, 84, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, L.; Larkum, A.W.D.; Trampe, E.; Norman, A.; Sørensen, S.J.; Kühl, M. Microbial diversity of biofilm communities in microniches associated with the didemnid ascidian Lissoclinum patella. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1222–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Komárek, J.; Komárková, J. Taxonomic review of the cyanoprokaryotic genera Planktothrix and Planktothricoides. Fottea 2004, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva Oliveira, F.A.; Colares, G.B.; Hissa, D.C.; Angelim, A.L.; Melo, V.M.M.; Lotufo, T.M.C. Microbial epibionts of the colonial ascidians Didemnum galacteum and Cystodytes sp. Symbiosis 2013, 59, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, E.; Turon, X.; López-Legentil, S.; Erwin, P.M.; Hirose, M. First records of didemnid ascidians harbouring Prochloron from Caribbean Panama: Genetic relationships between Caribbean and Pacific photosymbionts and host ascidians. Syst. Biodivers. 2012, 10, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donia, M.S.; Fricke, W.F.; Partensky, F.; Cox, J.; Elshahawi, S.I.; White, J.R.; Phillippy, A.M.; Schatz, M.C.; Piel, J.; Haygood, M.G.; et al. Complex microbiome underlying secondary and primary metabolism in the tunicate-Prochloron symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 1423–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donia, M.; Fricke, W.; Ravel, J.; Schmidt, E. Variation in tropical reef symbiont metagenomes defined by secondary metabolism. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, E.W. The secret to a successful relationship: Lasting chemistry between ascidians and their symbiotic bacteria. Invertebr. Biol. 2015, 134, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erwin, P.M.; Pineda, M.C.; Webster, N.; Turon, X.; López-Legentil, S. Down under the tunic: Bacterial biodiversity hotspots and widespread ammonia-oxidizing archaea in coral reef ascidians. ISME J. 2014, 8, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, Z.; Torres, J.P.; Tianero, M.D.; Kwan, J.C.; Schmidt, E.W. Origin of chemical diversity in Prochloron-tunicate symbiosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 3450–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tianero, M.D.B.; Kwan, J.C.; Wyche, T.P.; Presson, A.P.; Koch, M.; Barrows, L.R.; Bugni, T.S.; Schmidt, E.W. Species specificity of symbiosis and secondary metabolism in ascidians. ISME J. 2015, 9, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lopez-Guzman, M.; Erwin, P.M.; Hirose, E.; López-Legentil, S. Biogeography and host-specificity of cyanobacterial symbionts in colonial ascidians of the genus Lissoclinum. Syst. Biodivers. 2020, 18, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühl, M.; Chen, M.; Ralph, P.J.; Schreiber, U.; Larkum, A.W.D. A niche for cyanobacteria containing chlorophyll d. Nature 2005, 433, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrendt, L.; Larkum, A.; Norman, A.; Qvortrup, K.; Chen, M.; Ralph, P.; Sørensen, S.; Trampe, E.; Kühl, M. Endolithic chlorophyll d-containing phototrophs. ISME J. 2011, 5, 1072–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Behrendt, L.; Trampe, E.L.; Nord, N.B.; Nguyen, J.; Kühl, M.; Lonco, D.; Nyarko, A.; Dhinojwala, A.; Hershey, O.S.; Barton, H. Life in the dark: Far-red absorbing cyanobacteria extend photic zones deep into terrestrial caves. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 952–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, L.; Brejnrod, A.; Schliep, M.; Sørensen, S.J.; Larkum, A.W.; Kühl, M. Chlorophyll f-driven photosynthesis in a cavernous cyanobacterium. ISME J. 2015, 9, 2108–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trampczynska, A.; Küpper, H.; Meyer-Klaucke, W.; Schmidt, H.; Clemens, S. Nicotianamine forms complexes with Zn(ii) in vivo. Metallomics 2010, 2, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baur, P.; Comba, P.; Institute of Inorganic Chemistry, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany. 2022; Manuscript in preparation.

- Paul, V.J.; Arthur, K.E.; Ritson-Williams, R.; Ross, C.; Sharp, K. Chemical defenses: From compounds to communities. Biol. Bull. 2007, 213, 226–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flórez, L.V.; Biedermann, P.H.W.; Engl, T.; Kaltenpoth, M. Defensive symbioses of animals with prokaryotic and eukaryotic microorganisms. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 904–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindquist, N.; Hay, M.E.; Fenical, W. Defense of ascidians and their conspicuous larvae: Adult vs. larval chemical defenses. Ecol. Monogr. 1992, 62, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olson, R.R.; McPherson, R. Potential vs. realized larval dispersal: Fish predation on larvae of the ascidian Lissoclinum patella (Gottschaldt). J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 1987, 110, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, G.; Mitić, N.; Hanson, G.R.; Comba, P. Purple acid phosphatase: A journey into the function and mechanism of a colorful enzyme. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geier, B.; Sogin, E.M.; Michellod, D.; Janda, M.; Kompauer, M.; Spengler, B.; Dubilier, N.; Liebeke, M. Spatial metabolomics of in situ host–microbe interactions at the micrometre scale. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrendt, L.; Salek, M.M.; Trampe, E.L.; Fernandez, V.I.; Lee, K.S.; Kühl, M.; Stocker, R. PhenoChip: A single-cell phenomic platform for high-throughput photophysiological analyses of microalgae. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baur, P.; Kühl, M.; Comba, P.; Behrendt, L. Possible Functional Roles of Patellamides in the Ascidian-Prochloron Symbiosis. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/md20020119

Baur P, Kühl M, Comba P, Behrendt L. Possible Functional Roles of Patellamides in the Ascidian-Prochloron Symbiosis. Marine Drugs. 2022; 20(2):119. https://doi.org/10.3390/md20020119

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaur, Philipp, Michael Kühl, Peter Comba, and Lars Behrendt. 2022. "Possible Functional Roles of Patellamides in the Ascidian-Prochloron Symbiosis" Marine Drugs 20, no. 2: 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/md20020119

APA StyleBaur, P., Kühl, M., Comba, P., & Behrendt, L. (2022). Possible Functional Roles of Patellamides in the Ascidian-Prochloron Symbiosis. Marine Drugs, 20(2), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/md20020119