1. Introduction

Equine arteritis virus (EAV) is a prototype member of

Arteriviridae, a family of enveloped positive-stranded RNA viruses comprising porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), a major pathogen in the swine industry [

1]. EAV infects horses and donkeys and leads to abortions in pregnant mares and respiratory illness with flu-like symptoms, which can even lead to death in young animals. The virus is transmitted via the respiratory route and via the contaminated semen of previously infected stallions. Despite available vaccines, EAV remains an important pathogen in the horse industry [

2].

The infectious genomic RNA has a length of ~12 kbp, is 3′-polyadenylated, and presumably 5′-capped. The large replicase open reading frames (ORFs) 1a and 1b occupy most of the EAV genome and are directly translated from the genomic RNA [

1,

3]. However, the genes for the structural virion proteins, which are located at the 3’-end of the arterivirus genome, overlap with each other and are expressed from the 3’ co-terminal nested set of six leader-containing subgenomic RNAs [

4].

The structural proteins of arteriviruses include the nucleocapsid N and several membrane proteins, such as the Gp5/M dimer, the Gp2/3/4 complex, the small and hydrophobic E protein, and the ORF5a protein [

5]. All structural proteins, in addition to ORF5a, are essential for EAV infectivity; however, only N along with viral RNA and Gp5/M dimer is required for budding. Note that Gp2, Gp3, Gp4, and E are minor viral components, and knocking them out individually from EAV does not prevent the budding of non-infectious virus-like particles (VLPs) [

6]. If one of the genes encoding Gp2, Gp3, or Gp4 is deleted, the produced VLPs do not contain any Gp2/3/4 trimer component and have reduced the amount of the E protein. If the E protein is knocked out the Gp2/3/4 trimer, it is not incorporated into the virion particles, suggesting the involvement of E in the assembly of infectious particles containing the trimer [

6]. The trimer itself serves as a major tropism determinant for arteriviruses. The chimeric PRRSV arterivirus, containing E and Gp2/3/4 exchanged to homolog proteins of EAV, exhibits broadened cellular tropism of the EAV [

7]. In PRRSV, the Gp2/3/4 was shown to attach to the CD163 cellular receptor on the porcine alveolar macrophages [

8]. Recently, genome-edited pigs, lacking part of the CD163 receptor, were shown to be resistant to the PRRSV challenge [

9]. E is a small, hydrophobic protein suspected to serve as a viroporin [

10]. The Gp2 and Gp4 are type I integral membrane proteins [

5]. The Gp3 is a peculiar protein, which was shown to form a disulfide-linked trimer with only Gp2/4 in the virus particles, and the trimer cannot be detected in the infected cells [

11].

Intracellular localization of the minor proteins of EAV and other arteriviruses has not been studied in detail because of the problems associated with production of antibodies against these highly glycosylated proteins. In infected cells the E protein localizes mostly in the ER, and some fraction of it is presumably located in the Golgi, as it was shown to co-localize with Gp5 [

12]. Both Gp3 and Gp4, which were individually expressed (transfection with vaccinia system), were shown to co-localize with concanavalin A, an ER marker [

13]. It is not known wheather the Gp3 localizes beyond the ER and what is its localization in infected cells.

The location for arterivirus budding is not known. Previous studies have shown that arterivirus budding involves the wrapping of a preformed nucleocapsid by membranes in the ER or Golgi complex [

14,

15]. Moreover, infection with arteriviruses resulted in the re-arrangements of the internal membranes and formation of large numbers of double membrane vesicles (DMVs). For the formation of DMVs, non-structural proteins nsp2 and nsp3 are sufficient [

16].

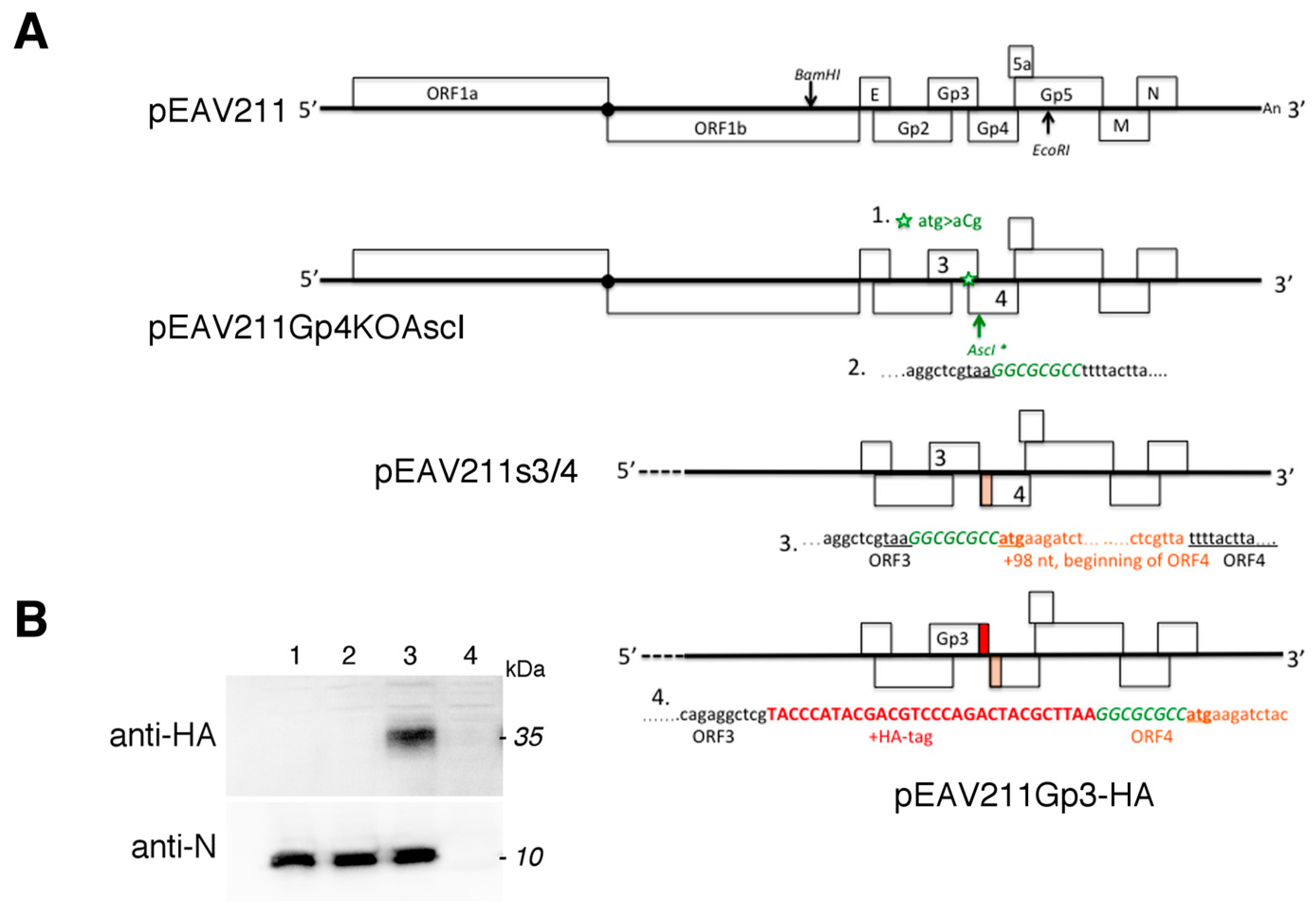

In this study, we created two recombinant EAV viruses: one with separated ORF3 and ORF4, and one with Gp3 and C-terminus HA-tag. The mutant viruses exhibited similar growth proprieties. Gp3-HA was incorporated into the virions and formed multimeric complexes, corresponding to the Gp2/3/4 trimer size. The EAVGp3-HA mutant enabled us to localize Gp3-HA using secretory pathway markers and other EAV proteins. We have shown that Gp3-HA have similar distribution as the E protein, i.e., it mainly localize in the ER, while some of it is moved to cis-Golgi. Finally, we demonstrated that the arterivirus genome tolerates the separation of the ORFs in virion structural genes and that the small tag can be introduced into Gp3 without loss in infectivity of the EAV virus. These results can be implemented for the development of new arteriviral vaccines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells and Media

The cell line BHK-21 (baby hamster kidney cells; ATCC C13) was maintained as an adherent culture in DMEM mixed in a 1:1 ratio with the Leibovitz L-15 medium (Cytogen, Lodz, Poland), which was supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Biological Industries, Cromwell, IA, USA), 100 U of penicillin per mL, and 100 mg of streptomycin and l-glutamine per mL (Biowest, Lodz, Poland). The cells were maintained at 37 °C in an atmosphere of air with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity.

2.2. Generation of Mutant EAV Genomes

Recombinant DNA techniques were performed according to standard protocols. Newly constructed plasmids were propagated in competent

Escherichia coli strain DH5alpha (Thermo Scientific, Warszawa, Poland). Cloning vector pEAV211, which is a derivate of the pEAV030 (Genbank Y07862.2) and described in reference [

17], was used to generate mutant EAVs. We generated specific DNA fragments by overlap extension PCR and purified them from the gel with the aid of the Gel-out kit (A&A Biotechnology, Gdansk, Poland). RGEAVBamHI and RGEAVEcoRI were used as an external primers. First, the translation initiation codon of the EAV ORF4 was mutated (ATG > ACG) with primers Gp4KOFor and Gp4KORev, and the 2.345 bp fragment cloned back to pEAV211 with the restriction enzymes

BamHI and

EcoRI (Thermo Scientific, Poland) to generate pEAV211Gp4KO. In the second step, the

AscI site was added after the stop codon of the ORF3 with primers EAV211AscIFor and EAV211AscIRev to generate the plasmid pEAV211Gp4KOAscI. The separation of the ORF3 and ORF4 was achieved by the overlap extension PCR with primers ReconAscGp4For and RGEAVEcoRI on the pEAV211 template and cloned to pEAV2114KOAscI with the

AscI and

EcoRI restriction enzymes to generate pEAV211s3/4. As the last step, the HA tag was added directly to ORF3’s 3’-end with the use of primers RGEAVBamHIIFor and EAVGp3HARev and pEAV211s3/4 as a DNA template. The ligation after

BamHI and

AscI restriction enzyme digestion of the 1657 bp product produced the pEAV211Gp3-HA vector. All of the generated plasmids were sequenced with the RGEAVEcoRIRev primer (Genomed, Warszawa, Poland).

Table 1 shows the list of used primers, while

Figure 1 shows the cloning schematics. All the genes that were subjected to mutations in plasmids were sequenced before use in experiments (Genomed, Warsaw, Poland).

2.3. RNA Transcription and Generation of Mutant EAVs

Full length clones pEAV211, pEAV211s3/4, and pEAV211Gp3-HA were linearized using XhoI and in vitro-transcribed using AmpliCap-Max T7 High Yield Message Maker Kit (Cellscript, Madison, WI, USA), and 6 µg RNA was then introduced into the BHK-21 cells suspended in PBS using the Gene Pulser Xcell electroporation apparatus and electroporation cuvettes with a 4-mm electrode gap (Bio-Rad, Warszawa, Poland). The cells were pulsed twice at 850 V, 25 F; resuspended in DMEM/L-15 5% FCS; and seeded into two wells of the 6-well plate. The cells were then maintained at 37 °C until the CPE was observed. The cells that adhered were detached using a plastic cell scraper and collected together in the supernatants. The cells were then centrifuged at a low speed. While half of the cells were subjected to RT-PCR and sequencing, the second half were subjected to western blotting with anti-N and anti-HA antibodies. The remaining supernatants were collected, aliquoted, and stored in −80 °C as a P0 stock.

2.4. In Vitro Growth Characteristics of Generated EAV Mutants

The monolayers of BHK-21 cells grown in 6-well plates were inoculated with each of the wild-type EAV-WT (derived from pEAV211), EAVs3/4, and EAVGp3-HA viruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The cells were then washed two times with PBS, with calcium and magnesium, and then overlaid with 2 mL of DMEM/L-15 1% FCS and 1% l-glutamine culture medium. At 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h post-infection, the supernatants were harvested and virus titers were determined on the BHK-21 cells using the plaque assay. Virus aliquots were stored at −80 °C. This experiment was carried out in triplicate.

2.5. Plaque Assay

Plaque assay was performed on the BHK-21 cells grown on 6-well plates with GMEM supplemented with 1% FCS, 1% L-glutamine, and 0.75% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC, Sigma-Aldrich, Poznań, Poland). The overlays were fixed with 10% formaldehyde and stained with crystal violet for three days p.i.

2.6. Stability of the HA-Tag

To determine the stability of the HA-tag fluorescence, the recombinant EAVGp3-HA virus was subjected to 19 sequential serial passages at an MOI of 1 in the BHK-21 cells. After the appearance of CPE, the supernatants were collected, centrifuged at a low speed, and stored in −80 °C. The remaining cells were washed with PBS, centrifuged, and stored in −80 °C for further RT-PCR and sequencing. To verify the stability of the HA-tag, the BHK-21 cells were grown on glass coverslips that were placed on a 24-well plate and infected with different passage recombinant viruses at an MOI of 1. 18h p.i. the cells were subjected to immunofluorescence with anti-HA tag antibodies (1:500, ab9110, Abcam, UK) and anti-N antibody (1:250, VMRD, USA), as has been described later in the Materials and Methods section. Furthermore, the infected cells from passages P7, P10, P15, and P19 were subjected for RT-PCR and sequencing.

2.7. RT-PCR and Sequencing

The total cellular RNA was extracted from transfected or infected cells (from 6-well plates each) with RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Wrocław, Poland) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA was generated with Maxima H minus First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo, Poland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with 2 µg of RNA and oligoT primer. The obtained cDNA was subjected to PCR reaction with EAVFor and EAVRev primers (each 10 mM) listed in

Table 1 and one-fusion high-speed-fidelity polymerase (GeneON, Abo, Poland). The thermal profile was as follows: initial denaturation at 98 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 46 °C for 20 s and extension at 72 °C for 20 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 3 min. The RT-PCR products were gel-purified using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, CA, USA), and the sense and antisense strands were sequenced (Eurofins MWG Operon, Huntsville, AL). The sequence data were analyzed using the software FinchTV 1.5.0. PCR products were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis, purified (Gel-Out, A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland), and the sense and antisense strands were sequenced (Genomed, Warsaw, Poland).

2.8. Analysis of the Gp3-HA Expression from Infected Cells

The BHK-21 cells seeded on 6-well plates were infected with P1 stock at an MOI of 1 or left mock infected. 18 h p.i. cells were detached using a plastic cell scraper, pelleted, and lysed either directly in the SDS sample buffer without DTT or resuspended in 80 µL 1× glycoprotein denaturing buffer and boiled for 10 min at 100 °C. To analyze glycosylation, the samples were digested with peptide-N-glycosidase (PNGase F; 5 U/L, 2 h at 37 °C) or endo-beta-N-acetyl-glucosaminidase (Endo H; 5 U/L, 1 h at 37 °C) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (New England BioLabs, Hitchin, UK). After the deglycosylation reaction, the samples were supplemented with reducing SDS-PAGE buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blotting.

2.9. Immunofluorescence Assay

The BHK-21 cells were seeded in the complete medium onto glass coverslips in 24-well plates. After 24 h, the cell culture medium was replaced with DMEM/L-15 medium with the cells infected with EAV wt, EAV s3/4, EAVGp3-HA, or left uninfected. After 2 h, the cells were washed two times with PBS and the cell culture medium was replaced with DMEM/L-15 containing 1% FCS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and, 1% l-glutamine. The cells were then fixed 18 h p.i. with paraformaldehyde (4% in PBS) for 15 min at room temperature (RT), washed twice with PBS, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton in PBS for 3 min at room temperature, and washed again twice with PBS. After blocking (blocking solution contained 3% bovine serum albumin in PBST) for 1 h at room temperature, the cells were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal anti-HA tag antibodies (1:500, ab9110, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and mouse monoclonal anti-N (1:250, VMRD, Pullman, WA, USA) antibody diluted in a blocking solution at room temperature for 1 h. These cells were then washed three times with PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies (1:800, goat anti-mouse IgG H&L Alexa Fluor 568 and 1:800 goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L Alexa Fluor 488, Abcam, UK). After immunostaining in all the cases, the cells were washed three times with PBS. Finally, the stained cultures were mounted on glass slides in a fluoroshield mounting medium with DAPI (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and stored at 4 °C.

The images were recorded using a Zeiss Cell Observer SD confocal microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with an EMCCD QImaging Rolera EM-C2 camera and 40–63× oil objectives (0.167 μm and 0.106 μm per pixel, respectively). The imaging was performed sequentially using 405 nm, 488 nm, and 561 nm laser lines with a quadruple dichroic mirror 405 + 488 + 561 + 640 and 450/50, 520/35, and 600/52 emission filters. Subsequently, the images were deconvoluted with Huygens software (SVI, Hilversum, The Netherlands).

2.10. Co-Localization Assay

For localization with cellular markers, the BHK-21 cells were infected with EAVGp3-HA at an MOI of 1 or left uninfected. The cells at 18 h p.i were subjected to immunofluorescence as described above with the following antibodies: rabbit polyclonal anti-HA tag antibodies (1:500, ab9110, Abcam, UK), mouse monoclonal anti-HA tag antibody (1:200, 16B12 Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA), mouse monoclonal anti-N antibody (1:250, VMRD, USA), rabbit anti-E antibodies, mouse monoclonal anti-PDI (1:250, 1D3, Enzo Life Sciences, USA), mouse monoclonal anti-membrin (1:100, 4HAD6, Enzo Life Sciences, USA), and mouse monoclonal anti-ERGIC (1:150, OTI1A8, Enzo Life Sciences, USA). Each co-localization experiment was conducted at least 3 times, and at least 10 cells were taken to quantify the co-localization in the JACoP plugin using the Fiji software.

2.11. Computer Analysis

In this study, all the graphs presented were created using GraphPad Prism 8 software. The significance was estimated using one-way ANOVA. The images were obtained from the confocal microscope were deconvoluted using Huygens Essential X11 (Scientific Volume Imaging, Hilversum, The Netherlands) and processed in ImageJ Fiji [

18]. The co-localization analyses were performed in ImageJ using the JACoP plugin [

19] in which Pearson’s and Mander’s coefficient were calculated. For each condition, at least 10 cells were taken for measurements of co-localization. Fluorescence intensities in the antibody accessibility experiment were measured as a mean gray value in ImageJ Fiji for 10 fields per condition.

2.12. SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

The detached and low-speed centrifuged, transfected, or infected cells were solubilized in the RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, Poland) with the complete protease inhibitor tablet (Roth, Sigma-Aldrich, Poland/Merc, Poland). Samples in the SDS-PAGE loading buffer, with or without DTT, were subjected to SDS-PAGE using 15% or 12% polyacrylamide. Then, the gels were blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (GE Healthcare, Warszawa, Poland). After blocking of the membranes (blocking solution; 5% skim milk powder in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST)) overnight at 4 °C, the antibodies in the blocking solution were incubated for 1.5 h at room temperature. Rabbit- anti-HA tag antibodies (1:6000); ab9110; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) were used to detect Gp3 with the HA tag, mouse monoclonal anti-N antibody (1:4000, VMRD, USA), and rabbit anti-E (1:1000, described in [

12], a gift from Eric Snijder, University of Leiden, Belgium). After washing (3 times for 10 min each with PBST), suitable horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies (1:4000; anti-rabbit or anti-mouse; Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) were applied for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with PBST, the signals were detected by chemiluminescence using the ECL plus reagent (Pierce/Thermo, Poland).

2.13. Immunoprecipitation

The BHK-21 cells seeded in T175 bottles were infected with EAVGp3-HA or mock infected at an MOI of 1. Two hours after infection cells were washed with PBS, and the cell culture medium was replaced with DMEM/L-15 containing 1% FCS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and, 1% l-glutamine. 22 h p.i. supernatants were collected and low-speed centrifuged to remove the cells. Then, the supernatants were subjected to purification and concentration on Amicon Ultra-15, Ultracel-100K filters (Merck, Warszawa, Poland). Briefly, 20 mL of cell-free supernatants were transferred to filters and centrifuged at 3500× g for 40 min at room temperature, to obtain 100 uL of concentrated supernatant. The SDS sample buffer with or without DTT was added to 5% of the volume of the obtained concentrated virions, while the remaining 95% was lysed in the MNT buffer (20 mM MES, 30 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 1% TX-100, pH 7.4) and subjected to IP with rabbit polyclonal anti-HA (ab9110; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) overnight at 4 °C. The antibody-protein complexes were pulled with A-Sepharose (Sigma-Aldrich, Poland), washed with MNT, boiled with reducing or non-reducing SDS buffer, and subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blotting as described above.

4. Discussion

In this study, we describe the successful design and characterization of recombinant EAV that have separated ORFs encoding minor structural glycoproteins Gp3 and Gp4, which were then used to derive recombinant EAV with HA-tagged Gp3. Tagging the proteins in viral context might be a good tool to study localization and protein–protein interactions, particularly if the antibodies against those proteins are difficult to obtain. In arteriviruses, tagging the structural proteins is difficult because of the overlapping ORFs and nested genome.

Previously, the separation of the overlapping ORFs in EAV genome was achieved only for ORF4 and 5, ORF 5 and 6, and for ORFs 4, 5, 6 [

23]. Moreover, a small 9 aa epitope was successfully added to the N terminus of the M protein (ORF6); however, the overlapping sequences between major structural protein coding gens ORFs 4, 5, and 6 are smaller compared to the overlap between genes coding for minor virion proteins. In the abovementioned studies, the introduction into the EAV genome composed of additional 17–41 nucleotides and was stable up to P2. In our study, we successfully introduced 136 nucleotides between structural virion genes and tested the stability of the expression of the HA-tag, which lasted till at least P15. This is a very stable tag expression comparing bigger tags, such as mCherry and GFP, which were introduced in parts of the genome encoding non-structural proteins that had fluorescent protein expression declining after a few passages [

24,

25].

These infectious clones, pEAV211s3/4 and pEAV211Gp3-HA, will enable easier mutagenesis on the C-terminus of the Gp3 and N-terminus of the Gp4 as changing the nt sequence of one ORF in particular regions will not influence the coding sequence in the other ORF.

In this study, we demonstrated that the addition of HA-tag to the Gp3 did not affect virus infectivity and replication. Gp3-HA was incorporated into the virions and was forming a multimeric structure, corresponding to the size of the Gp2/3/4 trimer. The trimer was not detected in infected cells, only in the virion, thus supporting earlier experiments [

11,

13]. The recombinant EAVGp3-HA will enable analysis of the entry of EAV as the information on the mechanisms of fusion and uncoating of the arteriviruses is still missing. Furthermore, the tagged protein could be used in proteomic experiments that explore host–virus interactions [

26]. Information that the EAV genome supports a stable tag in the structural protein could be useful for vaccine development of arterivirus, e.g., in the techniques of virion purification or marker vaccine development [

27].

In this study, we used the recombinant EAV to study the localization of the Gp3-HA. Previously, the localization of the Gp3 was tested in transfected cells only, and exclusively with the ER marker [

13]. As the incorporation of minor proteins is E dependent we also performed detailed co-localization of the E. Clearly, these membrane proteins poorly co-localized with N, which was shown to be primarily located in the cytoplasm (inside DMVs) [

28]. The Gp3-HA and E co-localized to some extent with each other, however we expected higher co-localization of those minor EAV proteins. Both Gp3-HA and E localized primarily in the ER, and some of the Gp3-HA was also found in the

cis-Golgi compartment. The E protein co-localized with

cis-Golgi to a lesser extent, then Gp3-HA, which can explain why the co-localization of the Gp3-HA and E was lower than expected.

Our study suggests that only a small fraction of the expressed Gp3-HA and an even smaller fraction of E protein was transported to the Golgi apparatus. The Gp3-HA and E did not co-localize in ERGIC; however, this does not rule it out as a budding site of Arteriviruses. Although the Gp3 does not contain any known ER retention motif, a majority of the protein was retained in the ER in our study. The

N-glycans of Gp3-HA were sensitive to endoglycosidase H, confirming that most of the protein remains in the ER. We observed some localization of Gp3-HA and E in the cis-Golgi, possibly because some of the Gp3-HA and E might have escaped from ER because of overexpression and was transported back from the Golgi to ER [

29].

Although expressed in high amounts in infected cells, only a small fraction of the E and minor glycoproteins Gp2, Gp3, and Gp4 end up in the virions [

6,

13]. A few reasons for this phenomenon are as follows. First, minor proteins might not be present at the assembly site. If Gp5/M, which is indispensable for VLPs formation, is located primarily in the Golgi, it could be the main budding site. In our study, we have shown that only some fraction of Gp3-HA is also located in the

cis-Golgi, while a majority of it seems to be retained in ER. Only properly folded and assembled transmembrane proteins are exported from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [

29]. It is possible that the complex Gp2/Gp4 dimer, as well as Gp3 and E, moved to the Golgi, while monomers remained in ER. Unfortunately, the Gp3-HA does not form a disulfide-linked trimer in the cell; therefore, we could not perform the fractionation of internal membranes to see if the Gp3-HA did move from the ER to the Golgi on oligomerization with Gp2 and Gp4. Disulfide-linked trimer formation is mediated after virion release, preferably at more basic pH [

11]. We also detected the higher forms of Gp3-HA in non-reducing conditions only in virions.

The site of arterivirus assembly is still not fully understood. Previous electron microscopy studies suggest budding from intracellular membranes: ER or Golgi [

14,

15]. Clearly, for the production of VLPs, the nucleocapsid N coupled with RNA and the Gp5/M heterodimer formation is essential [

6,

30]. This is in contrast to the assembly of

Coronaviridae (which are in the same order as

Arteriviridae—Nidovirales), in which only the M and E proteins drive virion budding [

31]. The failure to achieve budding by co-expression of only N, Gp5, and M without the EAV RNA suggests that there are additional factors in the EAV particle formation. It is possible that the arterivirus assembly is coupled to viral genome replication, interaction of RNA with structural proteins, or to the expression of non-structural proteins.

It has been shown primarily for other Nidovirales, such as the Coronaviruses, that the efficient incorporation of viral proteins into virions depends on two determinants, i.e., protein trafficking and interaction between proteins at the budding site, which in the case of Coronaviruses is ERGIC [

32]. However, the factors that control the site of budding in well-studied Coronaviruses are unknown. When expressed independently or during an infection, many coronaviral proteins pass through the ERGIC and localize in the Golgi complex, e.g., the spike S protein is expressed even on the plasma membrane [

33,

34].

In Arteriviruses, Gp5/M dimers, which are essential for EAV budding, were shown to be located primarily in the Golgi apparatus (co-localization with mannosidase II), although at subsequent time points of the infection, the M was also present in the ER [

35] and Golgi localization was not achieved if the dimer formation was blocked. If the budding occurs where the Gp5/M is localized, this could be the mechanism of lower incorporation into the virions of minor proteins, i.e., they are not abundant at the assembly site. In this study, we have shown that the Gp3-HA and E localized mainly in the ER. However, the mechanism of lower incorporation of the E and minor glycoproteins in Arteriviruses might be different, and not dependent on the localization of the proteins. In coronaviruses the E protein, which is essential for virion formation, remains at the budding site, but is incorporated into virions in small amounts, by unknown mechanism [

36]. In the influenza A virus the M2 protein is excluded from the budozone, presumably because it localizes at the edges of the lipid rafts at plasma membrane, the site of Infuenza A budding [

37,

38]. Further experiments are needed to explain lower incorporation of the minor proteins into EAV virions.