Behavior of Eosinophil Counts in Recovered and Deceased COVID-19 Patients over the Course of the Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Study

2.2. Laboratory Information

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Development

3.2. Demographics, Clinical Characteristics, and Diagnosis

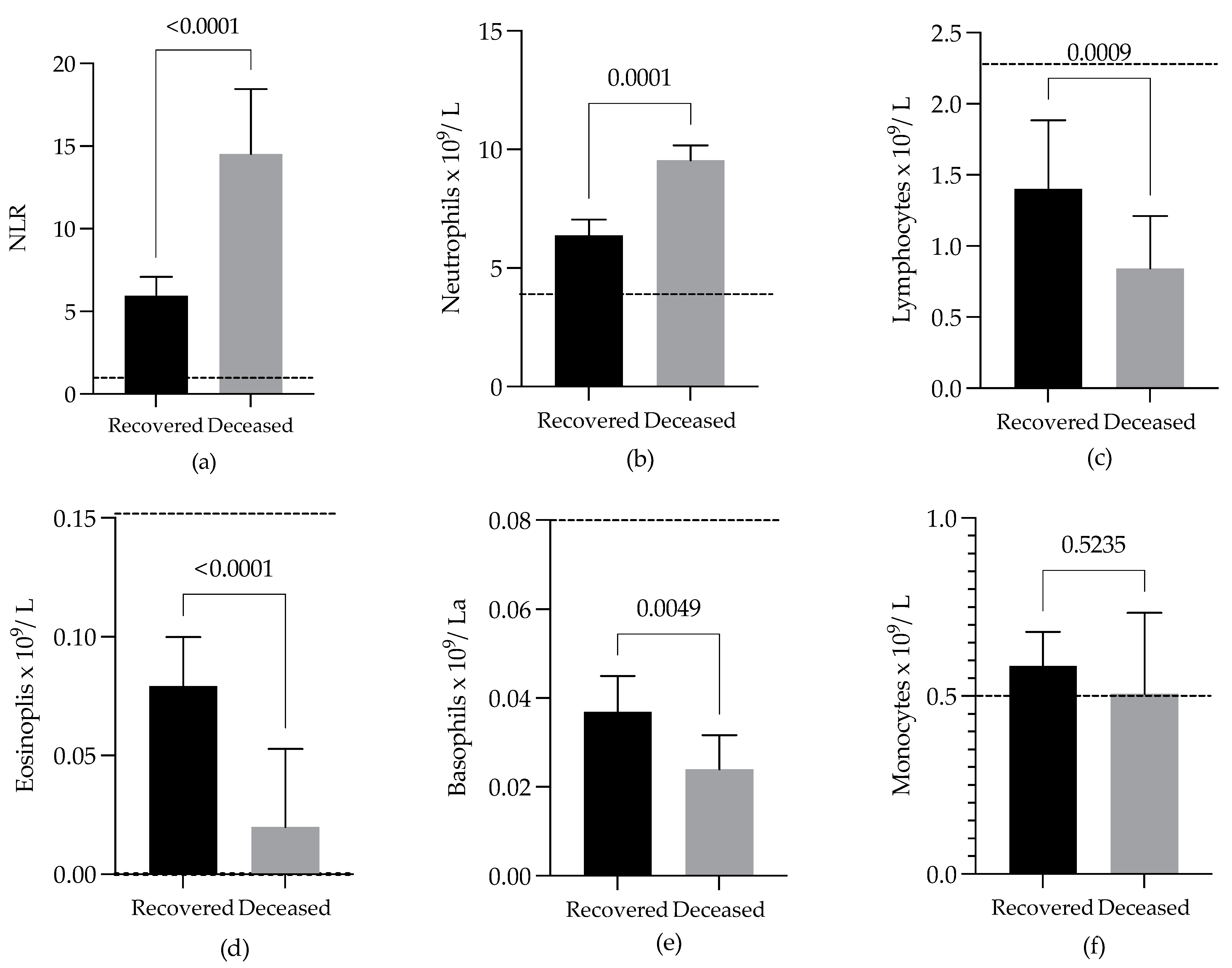

3.3. Comparison of NLRs and WBC Differential Counts of COVID-19 Patients with Different Outcomes

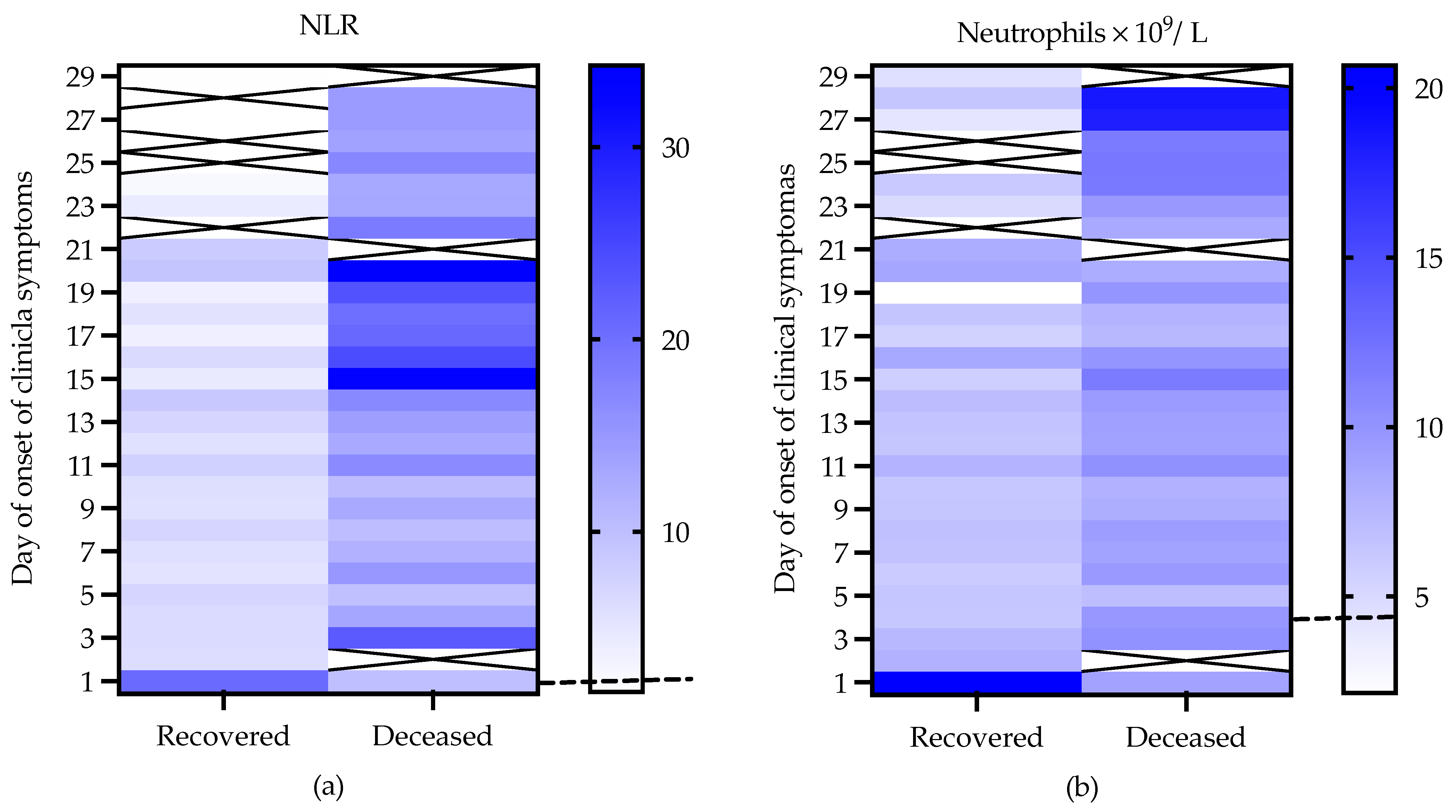

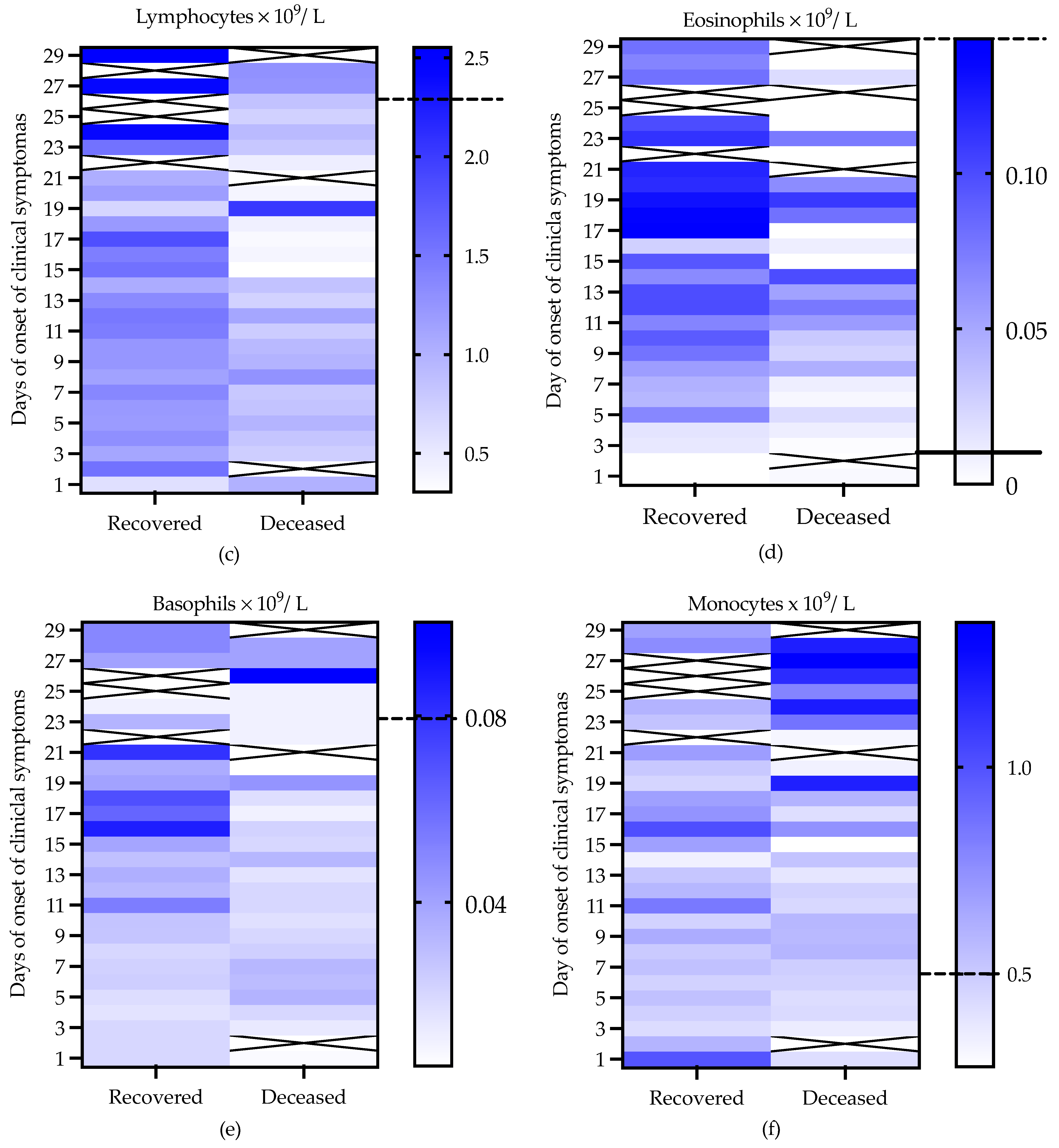

3.4. Behavior of NLRs and WBC Differential Counts in COVID-19 Patients with Outcomes of Recovery and Death over the Course of the Disease

4. Discussion

- (1)

- The fact that, on average, the eosinophil counts were higher in the recovered than in the deceased patients (Figure 2d);

- (2)

- Although both groups of patients presented eosinophil count values of zero in one or more of their WBC differential counts, this situation was more frequently observed in the deceased than in the recovered patients. Furthermore, on average, the eosinophil counts in the recovered patients increased faster, up to values greater than 0.1 × 109/L, than those in deceased patients over the course of the disease (Figure 3d);

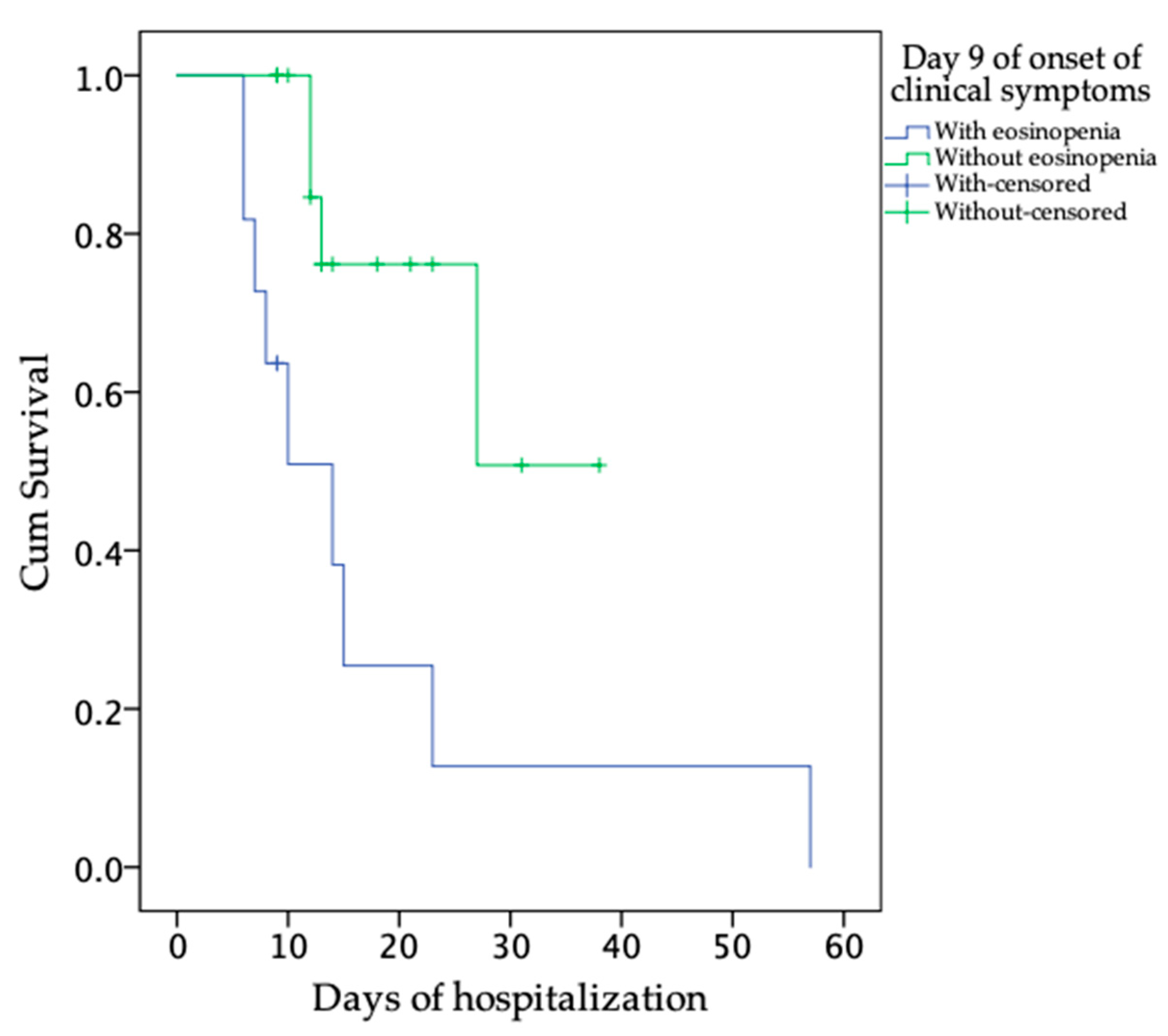

- (3)

- The estimated mean days of survival after admission was greater in the patients without eosinopenia at Day 9 of the onset of clinical symptoms than in the patients with eosinopenia at the same time (Figure 4);

- (4)

- As COVID-19 progresses, an elevated number of circulating neutrophils and elevated level of NLR have been shown to be an indicator of the severity of respiratory symptoms and poor clinical outcomes [4,40]. In this study, the recovered patients, but not deceased patients, showed high negative correlations between the eosinophil and neutrophil counts, as well as between the eosinophil counts and the NLR, at Day 9 of the onset of clinical symptoms (Figure 5a,b).

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harapan, H.; Itoh, N.; Yufika, A.; Winardi, W.; Keam, S.; Te, H.; Megawati, D.; Hayati, Z.; Wagner, A.L.; Mudatsir, M. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Literature Review. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 667–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Coronavirus Resource Center. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Sun, Y.; Dong, Y.; Wang, L.; Xie, H.; Li, B.; Chang, C.; Wang, F.S. Characteristics and prognostic factors of disease severity in patients with COVID-19: The Beijing experience. J. Autoimmun. 2020, 112, 102473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Sang, L.; Jiang, M.; Yang, Z.; Jia, N.; Fu, W.; Xie, J.; Guan, W.; Liang, W.; Ni, Z.; et al. Longitudinal hematologic and immunologic variations associated with the progression of COVID-19 patients in China. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 146, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Kong, J.; Wang, W.; Wu, M.; Yao, L.; Wang, Z.; Jin, J.; Wu, D.; Yu, X. The clinical implication of dynamic neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and D-dimer in COVID-19: A retrospective study in Suzhou China. Thromb. Res. 2020, 192, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.L.; Hou, Y.L.; Li, D.T.; Li, F.Z. Laboratory findings of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2020, 80, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.P.; Liu, J.P.; Tao, W.Q.; Li, H.M. The diagnostic and predictive role of NLR, d-NLR and PLR in COVID-19 patients. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 84, 106504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.; Zhou, L.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Tao, Y.; Xie, C.; Ma, K.; Shang, K.; Wang, W.; et al. Dysregulation of Immune Response in Patients with Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zini, G. Chapter 16—Abnormalities in leukocyte morphology and number. In Blood and Bone Marrow Pathology, 2nd ed.; Porwit, A., McCullough, J., Erber, W.N., Eds.; Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, UK, 2011; pp. 247–261. [Google Scholar]

- Shaaban, H.; Daniel, S.; Sison, R.; Slim, J.; Perez, G. Eosinopenia: Is it a good marker of sepsis in comparison to procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels for patients admitted to a critical care unit in an urban hospital? J. Crit. Care 2010, 25, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoignet, C.E.; Le Borgne, P.; Slimani, H.; Forato, M.; Kam, C.; Kauffmann, P.; Lefebvre, F.; Bilbault, P. Relevance of eosinopenia as marker of sepsis in the Emergency Department. Rev. Med. Interne 2016, 37, 730–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Tu, L.; Zhu, P.; Mu, M.; Wang, R.; Yang, P.; Wang, X.; Hu, C.; Ping, R.; Hu, P.; et al. Clinical Features of 85 Fatal Cases of COVID-19 from Wuhan. A Retrospective Observational Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, 1372–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, Q.; Hu, L.; Long, Y. Role of eosinophils in the diagnosis and prognostic evaluation of COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlini, S.; Ciprandi, G.; Castagnoli, R.; Licari, A.; Marseglia, G.L. Eosinopenia could be a relevant prognostic biomarker in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2020, 41, e80–e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.A.M.; Barros, I.C.A.; Jacob, A.L.V.; Assis, M.L.; Kanaan, S.; Kang, H.C. Laboratory findings in SARS-CoV-2 infections: State of the art. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2020, 66, 1152–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roca, E.; Ventura, L.; Zattra, C.M.; Lombardi, C. EOSINOPENIA: An early, effective, and relevant COVID-19 biomarker? QJM 2020, 114, 68–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanni, F.; Akker, E.; Zaman, M.M.; Figueroa, N.; Tharian, B.; Hupart, K.H. Eosinopenia and COVID-19. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2020, 120, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isobe, Y.; Kato, T.; Arita, M. Emerging roles of eosinophils and eosinophil-derived lipid mediators in the resolution of inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsley, A.W.; Schwartz, J.T.; Rothenberg, M.E. Eosinophil responses during COVID-19 infections and coronavirus vaccination. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 146, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, D.A. Behavior of eosinophil leukocytes in acute inflammation. II. Eosinophil dynamics during acute inflammation. J. Clin. Investig. 1975, 56, 870–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, E.A.; Zellner, K.R.; Colbert, D.; Lee, N.A.; Lee, J.J. Eosinophils regulate dendritic cells and Th2 pulmonary immune responses following allergen provocation. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 6059–6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, E.A.; Lesuer, W.E.; Willetts, L.; Zellner, K.R.; Mazzolini, K.; Antonios, N.; Beck, B.; Protheroe, C.; Ochkur, S.I.; Colbert, D.; et al. Eosinophil activities modulate the immune/inflammatory character of allergic respiratory responses in mice. Allergy 2014, 69, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outh, R.; Boutin, C.; Gueudet, P.; Suzuki, M.; Saada, M.; Aumaitre, H. Eosinopenia <100/μL as a marker of active COVID-19: An observational prospective study. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2021, 54, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Dong, X.; Cao, Y.Y.; Yuan, Y.D.; Yang, Y.B.; Yan, Y.Q.; Akdis, C.A.; Gao, Y.D. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy 2020, 75, 1730–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xu, A.; Zhang, Y.; Xuan, W.; Yan, T.; Pan, K.; Yu, W.; Zhang, J. Patients of COVID-19 may benefit from sustained Lopinavir-combined regimen and the increase of Eosinophil may predict the outcome of COVID-19 progression. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 95, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Cai, X.; Wang, H.; He, G.; Lin, Y.; Lu, B.; Chen, C.; Pan, Y.; Hu, X. Abnormalities of peripheral blood system in patients with COVID-19 in Wenzhou, China. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 507, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davido, B.; Partouche, B.; Jaffal, K.; de Truchis, P.; Herr, M.; Pepin, M. Eosinopenia in COVID-19: What we missed so far? J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi, G.; Henry, B.M. Eosinophil count in severe coronavirus disease 2019. QJM 2020, 113, 511–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Verdugo, F.; Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; Romero-Hernandez, F.; Coss-Adame, E.; Valdovinos, M.A.; Priego-Ranero, A.; Olvera-Prado, H.; Narvaez-Chavez, S.; Peralta-Figueroa, J.; Torres-Villalobos, G. Hematological indices as indicators of silent inflammation in achalasia patients: A cross-sectional study. Medicine 2020, 99, e19326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sysmex. Available online: https://www.sysmex.com/la/es/Controles/XN-CHECK_0178-10-11-XNL_PDF.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Olnes, M.J.; Kotliarov, Y.; Biancotto, A.; Cheung, F.; Chen, J.; Shi, R.; Zhou, H.; Wang, E.; Tsang, J.S.; Nussenblatt, R.; et al. Effects of Systemically Administered Hydrocortisone on the Human Immunome. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshehri, S.; Eljaaly, K.; Alshibani, M.; Katz, M. Impact of single-dose systemic glucocorticoids on blood leukocytes in hospitalized adults. J. Appl. Hematol. 2020, 11, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternak, Y.; Yarden-Bilavsky, H.; Kodman, Y.; Zoldan, M.; Tamary, H.; Ashkenazi, S. Inhaled corticosteroids increase blood neutrophil count by decreasing the expression of neutrophil adhesion molecules Mac-1 and L-selectin. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 34, 1977–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pountain, G.D.; Keogan, M.T.; Hazleman, B.L.; Brown, D.L. Effects of single dose compared with three days’ prednisolone treatment of healthy volunteers: Contrasting effects on circulating lymphocyte subsets. J. Clin. Pathol. 1993, 46, 1089–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Suarez, V.; Suarez Quezada, M.; Oros Ruiz, S.; Ronquillo De Jesus, E. Epidemiology of COVID-19 in Mexico: From the 27th of February to the 30th of April 2020. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2020, 220, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- © 2016–2021, Developed by the General Coordination of Social Communication. Government of the State of Michoacán 2015–2021. Available online: https://michoacan.gob.mx/prensa/discursos/pruebas-confirman-4-casos-positivos-de-covid-19-enmichoacan-2/ (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Bello-Chavolla, O.Y.; Bahena-Lopez, J.P.; Antonio-Villa, N.E.; Vargas-Vazquez, A.; Gonzalez-Diaz, A.; Marquez-Salinas, A.; Fermin-Martinez, C.A.; Naveja, J.J.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A. Predicting Mortality Due to SARS-CoV-2: A Mechanistic Score Relating Obesity and Diabetes to COVID-19 Outcomes in Mexico. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, 2752–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra-Bracamonte, G.M.; Lopez-Villalobos, N.; Parra-Bracamonte, F.E. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality of patients with COVID-19 in a large data set from Mexico. Ann. Epidemiol. 2020, 52, 93–98.e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechien, J.R.; Chiesa-Estomba, C.M.; Beckers, E.; Mustin, V.; Ducarme, M.; Journe, F.; Marchant, A.; Jouffe, L.; Barillari, M.R.; Cammaroto, G.; et al. Prevalence and 6-month recovery of olfactory dysfunction: A multicentre study of 1363 COVID-19 patients. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 290, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.J.; Ni, Z.Y.; Hu, Y.; Liang, W.H.; Ou, C.Q.; He, J.X.; Liu, L.; Shan, H.; Lei, C.L.; Hui, D.S.C.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, A.P.; Soliman, A.; Al Masalamani, M.A.; De Sanctis, V.; Nashwan, A.J.; Sasi, S.; Ali, E.A.; Hassan, O.A.; Iqbal, F.M.; Yassin, M.A. Clinical Outcome of Eosinophilia in Patients with COVID-19: A Controlled Study. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, e2020165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraisse, M.; Logre, E.; Mentec, H.; Cally, R.; Plantefeve, G.; Contou, D. Eosinophilia in critically ill COVID-19 patients: A French monocenter retrospective study. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, K.S.; Howell, D.; Rogers, L.; Narasimhan, B.; Verma, H.; Steiger, D. The Relationship between Asthma, Eosinophilia, and Outcomes in COVID-19 Infection. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021, 127, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferastraoaru, D.; Hudes, G.; Jerschow, E.; Jariwala, S.; Karagic, M.; de Vos, G.; Rosenstreich, D.; Ramesh, M. Eosinophilia in Asthma Patients Is Protective against Severe COVID-19 Illness. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 1152–1162.e1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ari, S.; Can, V.; Demir, O.F.; Ari, H.; Agca, F.V.; Melek, M.; Camci, S.; Dikis, O.S.; Huysal, K.; Turk, T. Elevated eosinophil count is related with lower anti-factor Xa activity in COVID-19 patients. J. Hematop. 2020, 13, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell-Diaz, A.M.; Mateos-Mayo, A.; Nieto-Benito, L.M.; Balaguer-Franch, I.; Hernandez de la Torre-Ruiz, E.; Lainez-Nuez, A.; Suarez-Fernandez, R.; Bergon-Sendin, M. Exanthema and eosinophilia in COVID-19 patients: Has viral infection a role in drug induced exanthemas? J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, e561–e563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sernicola, A.; Carnicelli, G.; Di Fraia, M.; Chello, C.; Furlan, C.; Muharremi, R.; Paolino, G.; Grieco, T. ‘Toxic erythema’ and eosinophilia associated with tocilizumab therapy in a COVID-19 patient. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, e368–e370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandolfo, M.; Romita, P.; Bonamonte, D.; Cazzato, G.; Hansel, K.; Stingeni, L.; Conforti, C.; Giuffrida, R.; Foti, C. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome to hydroxychloroquine, an old drug in the spotlight in the COVID-19 era. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, A.; Matthews, M.; Mairlot, M.; Nobile, L.; Fameree, L.; Jacquet, L.M.; Baeck, M. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome in a patient with COVID-19. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, e768–e700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesenak, M.; Brndiarova, M.; Urbancikova, I.; Rennerova, Z.; Vojtkova, J.; Bobcakova, A.; Ostro, R.; Banovcin, P. Immune Parameters and COVID-19 Infection—Associations With Clinical Severity and Disease Prognosis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Zhou, F.; Luo, L.; Xu, M.; Wang, H.; Xia, J.; Gao, Y.; Cai, L.; Wang, Z.; Yin, P.; et al. Haematological characteristics and risk factors in the classification and prognosis evaluation of COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2020, 7, e671–e678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, A.; Yun, Y.; Bui, D.V.; Nguyen, L.M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Mitani, A.; Sawada, S.; Hamada, S.; Asako, M.; et al. The multiple functions and subpopulations of eosinophils in tissues under steady-state and pathological conditions. Allergol. Int. 2021, 70, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Tani, Y.; Nakanishi, H.; Taguchi, R.; Arita, M.; Arai, H. Eosinophils promote resolution of acute peritonitis by producing proresolving mediators in mice. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corry, D.B.; Folkesson, H.G.; Warnock, M.L.; Erle, D.J.; Matthay, M.A.; Wiener-Kronish, J.P.; Locksley, R.M. Interleukin 4, but not interleukin 5 or eosinophils, is required in a murine model of acute airway hyperreactivity. J. Exp. Med. 1996, 183, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevaert, P.; Van Bruaene, N.; Cattaert, T.; Van Steen, K.; Van Zele, T.; Acke, F.; De Ruyck, N.; Blomme, K.; Sousa, A.R.; Marshall, R.P.; et al. Mepolizumab, a humanized anti-IL-5 mAb, as a treatment option for severe nasal polyposis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128, 989–995.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pala, D.; Pistis, M. Anti-IL5 Drugs in COVID-19 Patients: Role of Eosinophils in SARS-CoV-2-Induced Immunopathology. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 622554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Recovered | Deceased | Total | p (Recovered vs. Deceased) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 59 | n = 60 | n = 119 | ||

| Age groups (year) | ||||

| 20–26 | 2 (3.4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.7%) | >0.05 |

| 27–49 | ∗ 25 (42.4%) | 8 (13.3%) | 33 (27.7%) | <0.005 ∗ 0.0115 |

| 50–59 | 15 (25.4%) | 21 (35%) | 36 (30.3%) | >0.05 |

| 60–90 | 17 (28.8%) | 31 (51.7%) | 48 (40.3%) | 0.0076 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 21 (35.6%) | 19 (31.7%) | 40 (33.6%) | >0.05 |

| Male | ∗ 38 (64.4%) | 41 (68.3%) | 79 (66.4%) | >0.05 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Any | 30 (50.8%) | 32 (53.3%) | 62 (52.1%) | >0.05 |

| COPD | 5 (8.5%) | 3 (5%) | 8 (6.7%) | >0.05 |

| Smoking | 2 (3.4%) | 5 (8.3%) | 7 (5.9%) | >0.05 |

| Asthma | 1 (1.7%) | 2 (3.3%) | 3 (2.5%) | >0.05 |

| Obesity | 6 (10.2%) | 7 (11.7%) | 13 (10.9%) | >0.05 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1 (0.2%) | 4 (6.7%) | 5 (4.2%) | >0.05 |

| Hypertension | 16 (27.1%) | 27 (45%) | 43 (36.1%) | 0.0304 |

| Diabetes | 17 (28.8%) | 20 (33.3%) | 37 (31.0%) | >0.05 |

| Immunosuppression | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (1.7%) | 2 (1.7%) | >0.05 |

| Renal disease | 2 (3.4%) | 3 (5%) | 5 (4.2%) | >0.05 |

| Cancer (remission) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.8%) | >0.05 |

| Tuberculosis | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.7%) | 1 (0.8%) | >0.05 |

| Signs and symptoms upon admission | ||||

| Sudden start | 9 (15.3%) | 10 (16.7%) | 19 (16.0%) | >0.05 |

| Attack on the general state | 27 (45.7%) | 31 (51.7%) | 58 (48.7%) | >0.05 |

| Fever | 50 (84.7%) | 54 (90%) | 104 (87.4%) | >0.05 |

| Dry cough | 51 (86.4%) | 55 (91.7%) | 101 (84.9%) | >0.05 |

| Headache | 48 (81.4%) | 42 (70%) | 100 (84.0%) | >0.05 |

| Odynophagia | 20 (33.9%) | 19 (31.7%) | 39 (32.8%) | >0.05 |

| Myalgia | 39 (66.1%) | 41 (68.3%) | 80 (67.2%) | >0.05 |

| Arthralgia | 38 (64.4%) | 37 (61.7%) | 75 (63.0%) | >0.05 |

| Prostration | 5 (8.5%) | 6 (10%) | 11 (9.2%) | >0.05 |

| Rhinorrhea | 9 (15.3%) | 9 (15%) | 18 (15.1%) | >0.05 |

| Chills | 15 (25.4%) | 20 (33.3%) | 35 (29.4%) | >0.05 |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (6.8%) | 6 (10%) | 10 (8.4%) | >0.05 |

| Chest pain | 31 (52.5%) | 32 (53.3%) | 63 (53%) | >0.05 |

| Dyspnea | 53 (89.8%) | 50 (83.3%) | 103 (86.6%) | >0.05 |

| Dysgeusia | 1 (1.7%) | 5 (8.3% | 6 (5.0%) | >0.05 |

| Anosmia | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.3%) | 2 (1.7%) | >0.05 |

| Conjunctivitis | 8 (13.6%) | 4 (6.7%) | 12 (10.1%) | >0.05 |

| Coryza | 1 (1.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.8%) | >0.05 |

| Diarrhea | 5 (8.5%) | 12 (20%) | 17 (14.3%) | >0.05 |

| Unconscious | 2 (3.4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.7%) | >0.05 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Influenza-like illness | 6 (10.2%) | 10 (16.7%) | 16 (13.4%) | >0.05 |

| SARI | 53 (89.8%) | 50 (83.3%) | 103 (86.5%) | >0.05 |

| Clinical pneumonia | 20 (33.9%) | 23 (38.3%) | 43 (36.1%) | >0.05 |

| Radiographic pneumonia | 15 (25.4%) | 17 (28.3%) | 32 (26.9%) | >0.05 |

| Endotracheal intubation | 4 (6.8%) | 21 (35.0%) | 25 (21.1%) | <0.0002 |

| Medications | ||||

| Oseltamivir | 2 (3.4%) | 9 (15%) | 11 (9.2%) | >0.05 |

| Antibiotics | 8 (13.6%) | 18 (30%) | 26 (21.8%) | >0.05 |

| Tocilizumab | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.3%) | 2 (1.7%) | >0.05 |

| Corticosteroids | 32 (54.2 %) | 41 (68.3%) | 73 (61.3%) | >0.05 |

| Dexamethasone | 22 (37.3%) | 20 (33%) | 41 (34.5%) | >0.05 |

| Methylprednisolone | 16 (27.1%) | 10 (16.7%) | 16 (13.5%) | >0.05 |

| Hydrocortisone | 1 (1.6%) | 8 (13.3%) | 9 (7.6%) | 0.0322 |

| Prednisone | 2 (3.4%) | 5 (8.3%) | 7 (5.9%) | >0.05 |

| Inhaled budesonide and fluticasone | 1 (1.6%) | 5 (8.3%) | 6 (5.0%) | >0.05 |

| Two different corticosteroids | 1 (1.6%) | 13 (21.7%) | 14 (11.8%) | 0.0010 |

| Minimum | Maximum | Std. Error | Mean | Mean for Healthy Subjects ‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC counts | 3.2 | 25 | 0.23 | 9.6 ± 3.9 | 7.01 ± 1.45 |

| NLR | 1.08 | 58.88 | 0.55 | 10.5 ± 9.10 | 1.80 ± 0.65 |

| Neutrophils | 1.59 | 24.01 | 0.22 | 7.8 ± 3.7 | 3.96 ± 1.12 |

| Lymphocytes | 0.17 | 4.53 | 0.04 | 1.13 ± 0.70 | 2.31 ± 0.58 |

| Eosinophils | 0.0 | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.06 ± 0.07 | 0.15 ± 0.13 |

| Basophils | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.03 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ∗ |

| Monocytes | 0.07 | 2.2 | 0.02 | 0.55 ± 0.31 | 0.51 ± 0.14 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cortés-Vieyra, R.; Gutiérrez-Castellanos, S.; Álvarez-Aguilar, C.; Baizabal-Aguirre, V.M.; Nuñez-Anita, R.E.; Rocha-López, A.G.; Gómez-García, A. Behavior of Eosinophil Counts in Recovered and Deceased COVID-19 Patients over the Course of the Disease. Viruses 2021, 13, 1675. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13091675

Cortés-Vieyra R, Gutiérrez-Castellanos S, Álvarez-Aguilar C, Baizabal-Aguirre VM, Nuñez-Anita RE, Rocha-López AG, Gómez-García A. Behavior of Eosinophil Counts in Recovered and Deceased COVID-19 Patients over the Course of the Disease. Viruses. 2021; 13(9):1675. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13091675

Chicago/Turabian StyleCortés-Vieyra, Ricarda, Sergio Gutiérrez-Castellanos, Cleto Álvarez-Aguilar, Víctor Manuel Baizabal-Aguirre, Rosa Elvira Nuñez-Anita, Angélica Georgina Rocha-López, and Anel Gómez-García. 2021. "Behavior of Eosinophil Counts in Recovered and Deceased COVID-19 Patients over the Course of the Disease" Viruses 13, no. 9: 1675. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13091675

APA StyleCortés-Vieyra, R., Gutiérrez-Castellanos, S., Álvarez-Aguilar, C., Baizabal-Aguirre, V. M., Nuñez-Anita, R. E., Rocha-López, A. G., & Gómez-García, A. (2021). Behavior of Eosinophil Counts in Recovered and Deceased COVID-19 Patients over the Course of the Disease. Viruses, 13(9), 1675. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13091675