Barriers and Facilitators of Implementation of the Non-Hospital-Based Administration of Long-Acting Cabotegravir Plus Rilpivirine in People with HIV: Qualitative Data from the HOLA Study

Abstract

1. Background

2. Methods

3. Results

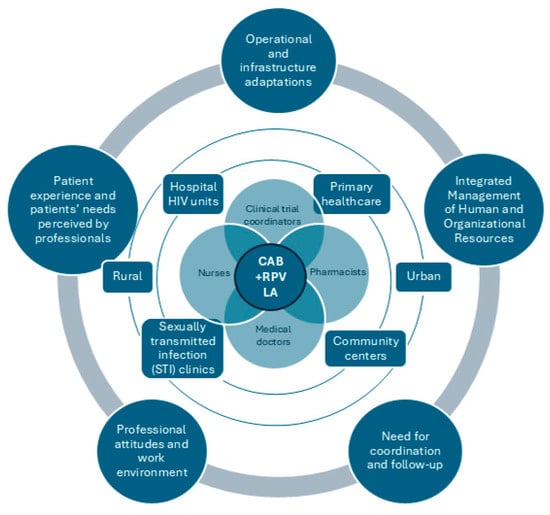

3.1. Operational and Infrastructure Adaptations

“It had to be set up in the outpatient day hospital. Two stretchers had to be placed in so that there would be two spaces where they could administer the medication.”Nurse 1

“It’s really important to make sure we have a system that avoids breaking the cold chain. That’s been the most complicated part of logistics for us.”Pharmacist

3.2. Integrated Management of Human and Organizational Resources

“We could use one person or more staff to accommodate and prepare all the medication. Or we could extend the administration schedule and accommodate more patients by having more working hours or more people.”Clinical trial coordinator 1

“The training for the nursing staff (in non-hospital facilities) should cover more than just drugs and administration. It should also include HIV, as specific knowledge is limited in the STI unit. And I imagine the same is true for Primary Healthcare Centers. Ultimately, to provide good patient care, we need to have training in the pathology itself.”Nurse 4

“I’d like to be able to do more things if I had more financial support. I’d be delighted, but I don’t know if I’m expecting it.”Physician 1

“I hope there’ll be no outside help, and, in fact, I don’t want there to be outside help, which in any case would come from the industry, and that has to be another medical process, right? In that sense, the industry should keep a healthy distance.”Physician 2

3.3. Need for Coordination and Follow-Up

“The main change has been how we’ve organized the logistics with the day hospital. This means that when the patient comes for their injection, they already have it, and we can check that they’re complying with the admin side of things. We’ve also set up an alert system for when a patient doesn’t come in, so we can let them know and look for them.”Physician 1

“I think it would be great to have a mobile app where people can communicate securely with the centers. They could also modify their appointments and have appointment reminders there to consult at any time.”Clinical trials coordinator 2

“The more we can adapt the schedules we offer them to fit in with their work life, the more we can help them, right? I think that’ll make it easier, because there are lots of people who, of course, if you limit yourself to Monday to Friday from 8 to 3… 70% of people work during those hours.”Nurse 1

“The main issue is when a patient doesn’t show up at the administration desk. This happens a lot because there can be medical reasons for this, like developing resistance or making things worse.”Physician 1

3.4. Professional Attitudes and Work Environment

“It’s the fear of the new. It’s as simple as that. It’s the fear of the unknown. That’s why so many centers have not wanted to participate or have not yet implemented it.”Physician 2

“I think motivation is key. It’s down to the person in charge to get it going. With desire, you can achieve a lot and make things easy. But if you force it, it won’t work.”Physician 3

“It’s important that the people running the service understand the case. The first thing we did was talk to the management to explain it. My hospital is very supportive of all-day hospital measures, and we haven’t had any problems with that. But it makes sense that, in the day hospital, the people running the day hospital have to approve it, which is what’s happened in our case.”Physician 1

3.5. Patient Experience and Needs Perceived by Professionals

“We’re saving them from having to make a 70 km one-way trip and then a 70 km return trip […] I’d say that most people prefer the hospital because it gives them more of a sense of security, and there are HIV doctors around.”Physician 2

“As the months go by, they are happier, especially because they don’t have to worry about the pill.”Nurse 4

“If you normalise it a little bit more, as the person who comes to get any other intramuscular treatment, you can also help to destigmatize it in the face of healthcare personnel, where stigma also exists.”Nurse 4

“Some patients don’t want to know anything about their health centre, but it’s not because of anything the centre does, it’s just that the quotas are based on geography.” “These are the streets that are right next to yours, in your neighbourhood. You don’t want anyone to know that you go to the health centre every two months to get a shot. So, there are people who prefer the anonymity of the hospital, and there are people who prefer to be pricked at their health centre.”Physician 2

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Considerations for Implementation

4.2. Patient-Centered Considerations

4.3. Limitations and Next Steps

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LA | Long-acting |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| CAB+RPV | Cabotegravir and rilpivirine |

| CFIR | Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research |

| PWH | People with HIV |

| AEs | Adverse events |

References

- Mussini, C.; Cazanave, C.; Adachi, E.; Eu, B.; Alonso, M.M.; Crofoot, G.; Chounta, V.; Kolobova, I.; Sutton, K.; Sutherland-Phillips, D.; et al. Improvements in Patient-Reported Outcomes After 12 Months of Maintenance Therapy with Cabotegravir + Rilpivirine Long-Acting Compared with Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide in the Phase 3b SOLAR Study. AIDS Behav. 2024, 29, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsson-Oldenbuttel, C.; Noe, S.; Wyen, C.; Borch, J.; Ummard-Berger, K.; Postel, N.; Scholten, S.; Dymek, K.M.; Westermayer, B.; de los Rios, P.; et al. 12-Month Outcomes of Cabotegravir Plus Rilpivirine Long-Acting Every 2 Months in a Real-World Setting: Effectiveness, Adherence to Injections, and Patient-Reported Outcomes from People with HIV-1 in the German CARLOS Study Who Switched off Suppressive Oral Daily ART. In Proceedings of the AIDS 2024, the 25th International AIDS Conference, Munich, Germany, 22–26 July 2024; Available online: https://www.natap.org/2024/IAS/IAS_41.htm (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Antinori, A.; Vergori, A.; Ripamonti, D.; Valenti, D.; Esposito, V.; Carleo, M.A.; Rusconi, S.; Cascio, A.; Manzillo, E.; Andreoni, M.; et al. Investigating coping and stigma in people living with HIV through narrative medicine in the Italian multicentre non-interventional study DIAMANTE. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutner, C.; Harrington, C.; Bontempo, G.; Pazhamalai, S.; Kumar, A.; Rimler, K.; Davis, K.; Williams, W.; Merrill, D.; Petty, L.; et al. P545. Feasibility, Fidelity, and Effectiveness of Administering Cabotegravir + Rilpivirine Long-Acting (CAB + RPV LA) in Infusion Centers. In Proceedings of the ID Week 2024, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 16–19 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gutner, C.A.; Hocqueloux, L.; Jonsson-Oldenbüttel, C.; Vandekerckhove, L.; van Welzen, B.J.; Slama, L.; Crusells-Canales, M.; Sierra, J.O.; DeMoor, R.; Scherzer, J.; et al. Implementation of long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine: Primary results from the perspective of staff study participants in the Cabotegravir And Rilpivirine Implementation Study in European Locations. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2024, 27, e26243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Welzen, B.J.; Vandekerckhove, L.; Jonsson-Oldenbüttel, C. Implementation of Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine Long-Acting (CAB + RPV LA): Primary Results from the CAB + RPV Implementation Study in European Locations (CARISEL). 2022. Available online: https://www.natap.org/2022/Glascow/GLASGOW_03.htm (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- De Wit, S.; Rami, A.; Bonnet, F.; DeMoor, R.; Bontempo, G.; Latham, C.; Gill, M.; Hadi, M.; Cooper, O.; Anand, S.B.; et al. 1584. CARISEL A Hybrid III Implementation Effectiveness Study of implementation of Cabotegravir plus Rilpivirine Long Acting (CAB+RPV LA) in EU Health Care Settings Key Clinical and Implementation Outcomes by Implementation Arm. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9 (Suppl. S2), ofac492.107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkin, C.; Hayes, R.; Haviland, J.; Wong, Y.L.; Ring, K.; Apea, V.; Kasadha, B.; Clarke, E.; Byrne, R.; Fox, J.; et al. Perspectives of People with Human Immunodeficiency Virus on Implementing Long-acting Cabotegravir Plus Rilpivirine in Clinics and Community Settings in the United Kingdom: Results from the Antisexist, Antiracist, Antiageist Implementing Long-acting Novel Antiretrovirals Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 80, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, A.; Carrillo, I.; Al-Hayani, A.; López De Las Heras, M.; Algar, C.; Burillo, I.; Álvarez-Álvarez, B.; Prieto-Pérez, L.; Mahillo-Fernández, I.; Bonilla, M.; et al. ACCEPTABILITY & FEASIBILITY interventions measures (AIM & FIM) of the implementation of long-acting cabotegravir plus rilpivirine (CAB LA + RPV LA) administration out of HIV units: The IMADART study. In Proceedings of the ESCMID Global, Vienna, Austria, 11–15 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cabello, A. Feasibility and satisfaction of interventions measures (FIM and HIVTSQ) of implementation of long-acting CAB + RPV administration out of HIV units: The IMADART study. In Proceedings of the HIV Glasgow, Glasgow, UK, 10–13 November 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkin, C.; Oka, S.; Philibert, P.; Brinson, C.; Bassa, A.; Gusev, D.; Degen, O.; García, J.G.; Morell, E.B.; Tan, D.H.S.; et al. Long-acting cabotegravir plus rilpivirine for treatment in adults with HIV-1 infection: 96-week results of the randomised, open-label, phase 3 FLAIR study. Lancet HIV 2021, 8, e185–e196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadu, M.K.; Stolee, P. Facilitators and barriers of implementing the chronic care model in primary care: A systematic review. BMC Fam. Pract. 2015, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Tan, J.Y.; Liu, X.L.; Zhao, I. Barriers and enablers to implementing clinical practice guidelines in primary care: An overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e062158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davy, C.; Bleasel, J.; Liu, H.; Tchan, M.; Ponniah, S.; Brown, A. Effectiveness of chronic care models: Opportunities for improving healthcare practice and health outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negredo, E.; Hernández-Sánchez, D.; Álvarez-López, P.; Falcó, V.; Rivero, À.; Jusmet, J.; Palomo, M.Á.C.; de la Cruz, A.B.F.; Pavón, J.M.; Llavero, N.; et al. Exploring the acceptability, appropriateness, feasibility and satisfaction of an implementation strategy for out-of-HOspital administration of the Long-Acting combination of cabotegravir and rilpivirine as an optional therapy for HIV in Spain (the HOLA study)—A hybrid implementation-effectiveness, phase IV, double-arm, open-label, multicentric study: Study protocol. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e088514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. Demystification and Actualisation of Data Saturation in Qualitative Research Through Thematic Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2024, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Sefcik, J.S.; Bradway, C. Characteristics of Qualitative Descriptive Studies: A Systematic Review. Res. Nurs. Health 2017, 40, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colorafi, K.J.; Evans, B. Qualitative Descriptive Methods in Health Science Research. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2016, 9, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandelowski, M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res. Nurs. Health 2010, 33, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, D.; Beck, C. Essentials of Nursing Research, 9th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, C.; Palmgren, P.J.; Liljedahl, M. Twelve tips for conducting qualitative research interviews. Med. Teach. 2019, 41, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korstjens, I.; Moser, A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 24, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.L.; Adkins, D.; Chauvin, S. A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agovi, A.M.-A.; Thompson, C.T.; Craten, K.J.; Fasanmi, E.; Pan, M.; Ojha, R.P.; Thompson, E.L. Patient and clinic staff perspectives on the implementation of a long-acting injectable antiretroviral therapy program in an urban safety-net health system. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2024, 5, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGowan, J.P.; Fine, S.M.; Vail, R.M.; Merrick, S.T.; Radix, A.E.; Gonzalez, C.J.; Hoffmann, C.J.; Medical Care Criteria Committee. Use of Injectable CAB/RPV LA as Replacement ART in Virally Suppressed Adults. 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572795/ (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Czarnogorski, M.; Garris, C.P.; Dalessandro, M.; D’AMico, R.; Nwafor, T.; Williams, W.; Merrill, D.; Wang, Y.; Stassek, L.; Wohlfeiler, M.B.; et al. Perspectives of healthcare providers on implementation of long-acting cabotegravir plus rilpivirine in US healthcare settings from a Hybrid III Implementation-effectiveness study (CUSTOMIZE). J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2022, 25, e26003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolayemi, O.; Bogart, L.M.; Storholm, E.D.; Goodman-Meza, D.; Rosenberg-Carlson, E.; Cohen, R.; Kao, U.; Shoptaw, S.; Landovitz, R.J.; Sued, O. Perspectives on preparing for long-acting injectable treatment for HIV among consumer, clinical and nonclinical stakeholders: A qualitative study exploring the anticipated challenges and opportunities for implementation in Los Angeles County. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutner, C.A.; van der Valk, M.; Portilla, J.; Jeanmaire, E.; Belkhir, L.; Lutz, T.; DeMoor, R.; Trehan, R.; Scherzer, J.; Pascual-Bernáldez, M.; et al. Patient Participant Perspectives on Implementation of Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine: Results From the Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine Implementation Study in European Locations (CARISEL) Study. J. Int. Assoc. Provid. AIDS Care 2024, 23, 23259582241269837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantsios, A.; Murray, M.; Karver, T.S.; Davis, W.; Galai, N.; Kumar, P.; Swindells, S.; Bredeek, U.F.; García, R.R.; Antela, A.; et al. Multi-level considerations for optimal implementation of long-acting injectable antiretroviral therapy to treat people living with HIV: Perspectives of health care providers participating in phase 3 trials. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazuardi, E.; Newman, C.; Anintya, I.; Rowe, E.; Wirawan, D.N.; Wisaksana, R.; Subronto, Y.W.; Kusmayanti, N.A.; Iskandar, S.; Kaldor, J.; et al. Increasing HIV treatment access, uptake and use among men who have sex with men in urban Indonesia: Evidence from a qualitative study in three cities. Health Policy Plan. 2019, 35, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweitzer, A.M.; Dišković, A.; Krongauz, V.; Newman, J.; Tomažič, J.; Yancheva, N. Addressing HIV stigma in healthcare, community, and legislative settings in Central and Eastern Europe. AIDS Res. Ther. 2023, 20, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueda, S.; Mitra, S.; Chen, S.; Gogolishvili, D.; Globerman, J.; Chambers, L.; Wilson, M.; Logie, C.H.; Shi, Q.; Morassaei, S.; et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: A series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turan, B.; Budhwani, H.; Fazeli, P.L.; Browning, W.R.; Raper, J.L.; Mugavero, M.J.; Turan, J.M. How Does Stigma Affect People Living with HIV? The Mediating Roles of Internalized and Anticipated HIV Stigma in the Effects of Perceived Community Stigma on Health and Psychosocial Outcomes. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gender | |

| Man Woman N/A | 6 6 1 |

| Age | 44.00 (±10.86) * |

| Region | |

| Barcelona Malaga | 9 4 |

| Profession | |

| Trial coordinator Pharmacist Nurse Physician | 3 1 4 5 |

| Years of professional experience | 16.23 (±10.03) * |

| Category | Subcategory |

|---|---|

| Operational and infrastructure adaptations |

|

| Integrated management of human and organizational resources |

|

| Need for coordination and follow-up |

|

| Professional attitudes and work environment |

|

| Patient experience and patients’ needs perceived by professionals |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hernández-Sánchez, D.; Leyva-Moral, J.M.; Olalla, J.; Negredo, E.; on behalf of the HOLA Study Group. Barriers and Facilitators of Implementation of the Non-Hospital-Based Administration of Long-Acting Cabotegravir Plus Rilpivirine in People with HIV: Qualitative Data from the HOLA Study. Viruses 2025, 17, 993. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17070993

Hernández-Sánchez D, Leyva-Moral JM, Olalla J, Negredo E, on behalf of the HOLA Study Group. Barriers and Facilitators of Implementation of the Non-Hospital-Based Administration of Long-Acting Cabotegravir Plus Rilpivirine in People with HIV: Qualitative Data from the HOLA Study. Viruses. 2025; 17(7):993. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17070993

Chicago/Turabian StyleHernández-Sánchez, Diana, Juan M. Leyva-Moral, Julian Olalla, Eugènia Negredo, and on behalf of the HOLA Study Group. 2025. "Barriers and Facilitators of Implementation of the Non-Hospital-Based Administration of Long-Acting Cabotegravir Plus Rilpivirine in People with HIV: Qualitative Data from the HOLA Study" Viruses 17, no. 7: 993. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17070993

APA StyleHernández-Sánchez, D., Leyva-Moral, J. M., Olalla, J., Negredo, E., & on behalf of the HOLA Study Group. (2025). Barriers and Facilitators of Implementation of the Non-Hospital-Based Administration of Long-Acting Cabotegravir Plus Rilpivirine in People with HIV: Qualitative Data from the HOLA Study. Viruses, 17(7), 993. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17070993