Abstract

Background and Clinical significance: Plummer–Vinson (PV) syndrome is a rare medical entity diagnosed when iron-deficiency anemia, dysphagia, and esophageal webs occur in the same patient. PV syndrome has been associated with different autoimmune diseases, such as celiac disease (CD). CD is a chronic multisystemic disorder affecting the small intestine, but it is recognized as having a plethora of clinical manifestations secondary to the malabsorption syndrome that accompanies the majority of cases. However, similar to PV syndrome, a high percentage of CD patients are asymptomatic, and those who are symptomatic may present with a wide variety of gastrointestinal and extraintestinal symptoms, including iron-deficiency anemia, making the diagnosis challenging. Case presentation: We present the case of a 43-year-old Caucasian female patient with a 7-year history of iron-deficiency anemia and increased bowel movements (3–4 stools/day). Upper endoscopy demonstrated a narrowing at the proximal cervical esophagus from a tight esophageal stricture caused by a smooth mucosal diaphragm. A 36F Savary–Gilliard dilator was used to manage the stenosis. The distal esophagus and stomach were normal, but scalloping of the duodenal folds was noted, and CD was confirmed by villous atrophy and positive tissue transglutaminase antibodies. Dysphagia was immediately resolved, and a glute-free diet was implemented. Conclusions: The relationship between PV syndrome and CD is still a matter of debate. Some might argue that PV syndrome is a complication of an undiagnosed CD. In cases of PV syndrome, a CD diagnosis should be considered even in the absence of typical symptoms of malabsorption.

1. Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is a common autoimmune condition with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 1%. CD is characterized by a wide range of both intestinal and extraintestinal manifestations. Well-established CD may be complicated by iron deficiency and anemia, but they may also be the presenting clinical features in the absence of diarrhea or weight loss [1]. Plummer–Vinson syndrome (PV), also referred to as Paterson–Kelly syndrome, is an infrequent cause of sideropenic dysphagia characterized by the presence of upper esophageal webs, iron-deficiency anemia, and post-cricoid dysphagia [2]. This condition was first described over 100 years ago at the Mayo Clinic by two physicians, Henry Stanley Plummer and Porter Paisley Vinson, who speculated that spasm of the cardia and angulation of the esophagus were responsible for the symptomatology [3,4]. Later on, Donald Ross Paterson and Adam Brown-Kelly detected the presence of anemia and post-cricoid webbing in patients with dysphagia [5,6]. Therefore, a new syndrome emerged and was referred to as the Paterson–Brown–Kelly syndrome [5]. The association of the two conditions (CD and PV syndrome), although intimately linked by the presence of iron-deficiency anemia, is surprisingly uncommon [7]. However, PV recognition is important to identify patients with an increased risk of malignancy of the pharynx and esophagus [8]. PV syndrome occurs among white middle-aged women, yet the syndrome has been described in children and adolescents [9]. The exact etiopathogenesis is still unknown. Researchers have reported a susceptible genetic background, malnutrition, and the occurrence of autoimmune diseases as etiological factors for PV syndrome [10]. We report the case of a middle-aged female patient with CD who presented with PV syndrome.

2. Case Presentation

We present the case of a 43-year-old Caucasian female patient with a 7-year history of iron-deficiency anemia and increased bowel movements (3–4 stools/day). She failed to improve with oral iron replacement therapy, which she was taking regularly for a few years. She was otherwise in good health, but more recently, she developed dysphagia for solid foods and weight loss, and her general practitioner referred her to the gastroenterology department.

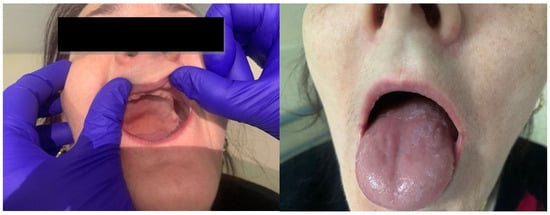

Her history and family history were unremarkable. On physical examination, she had a normal body temperature of 36.9 °C, her blood pressure was 117/67 mmHg, her heart rate was 71 beats per minute, her respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute, and her oxygen saturation was 97% in room air. Her physical examination showed a slender, thin patient with pale skin, a smooth tongue, angular cheilitis, and total edentulism (Figure 1). Her body mass index was 20 kg/m2. Abdominal palpation revealed no abdominal masses.

Figure 1.

Clinical examination revealing total edentulism, smooth tongue, and angular cheilitis.

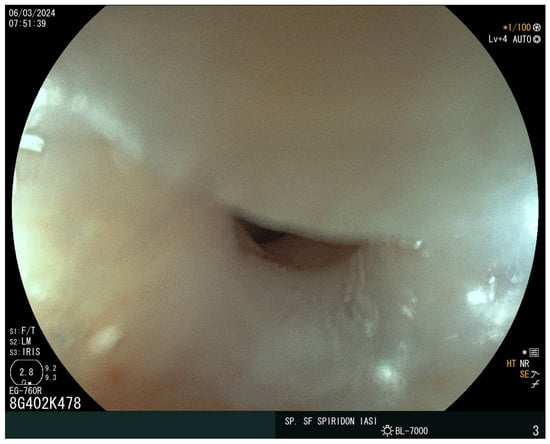

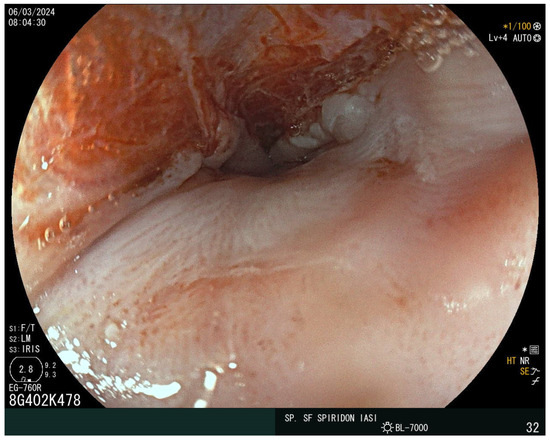

The laboratory findings noted iron-deficiency anemia with a hemoglobin level of 9 g/dL, with a mean corpuscular volume of 63 fL, a mean corpuscular hemoglobin of 18 pg, and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration of 27 g/dL. The eosinophil and immunoglobulin E values were normal. A decreased value of serum iron of 5 mcg/dl and ferritin of 15 ng/mL were also detected. Cholesterol and albumin levels and prolonged coagulation time were also reported as being below the normal range. The vitamin D, calcium, and folic acid levels were lower but within the normal range. Stool assessment ruled out an infectious cause, including parasitic infestation. The patient did not report rectal bleeding. Abdominal ultrasound showed no atypical findings. The plain chest X-ray revealed no abnormalities. Given the presence of iron-deficiency anemia and increased bowel movements, CD was suspected. The serum antibodies showed an elevated level of immunoglobulin A (IgA) anti-gliadin antibodies of 96 IU/mL and anti-transglutaminase antibodies (anti-tTG) of 215 IU/mL. Upper endoscopy demonstrated a narrowing at the proximal cervical esophagus from a tight esophageal stricture caused by a smooth mucosal diaphragm (Figure 2). No biopsies were taken during the baseline endoscopy. A 36F Savary–Gilliard dilator was used to manage the stenosis. Dysphagia was immediately resolved (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

The Plummer–Vinson web.

Figure 3.

Post-dilation endoscopic view using the Savary–Gilliard bougies.

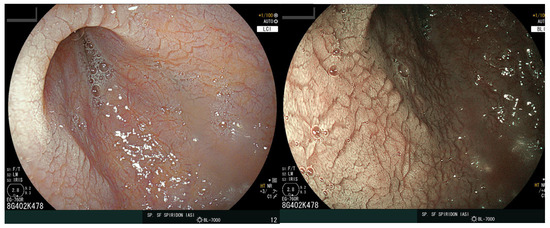

The distal esophagus and stomach were normal, but scalloping of the duodenal folds was noted (Figure 4), and numerous biopsy samples were taken confirming the diagnosis of CD with complete villous atrophy (Marsh 3c). Treatment options included a gluten-free diet and the continuation of iron supplementation. After the two-month follow-up appointment, the patient was in good health with no digestive complaints.

Figure 4.

Endoscopic view of the duodenum. The images display a loss of folds with a granular appearance, visible fissures, and a scalloping aspect of the mucosa.

3. Discussion

Although frequent and almost always asymptomatic, esophageal webs are common endoscopic discoveries that occur in 5–15% of cases with progressive or acute dysphagia to solids [11]. They present as indentations of the esophageal wall composed of one or more thin horizontal membranes of stratified squamous epithelium in the cervical esophagus and mid esophagus, which may hinder the passage of solid foods [12]. The main symptom associated with the presence of esophageal webs is painless and slowly progressing (over years) dysphagia, which becomes clinically significant when the luminal diameter of the esophagus is reduced to less than 12 mm, leading to food impaction [13]. It is theorized that iron deficiency induces esophageal web development by the reduction in or loss of iron-dependent enzymes, resulting in mucosal damage and vicious healing [14]. Chronic inflammation, which represents a shared pathogenic link, provides an explanation for the many clinical correlations [14,15].

The relationship between PV syndrome and CD remains unclear [2]. Some might argue that their association is not causal, while others find common etiopathogenic ground [16,17]. CD is an autoimmune enteropathy triggered by gluten consumption. The gliadin activates the immune system via the key enzyme tissue transglutaminase, enabling mucosal damage and atrophy and antibody formation [1,16]. Similar mechanisms may be involved in web formation in PV, but the most accurate assumption we can make to date is that CD may be the etiological factor for iron-deficiency anemia in PVs. Other immunological mechanisms, if involved, need to be further investigated [18].

In a retrospective study of over 18 years by Bakari et al., the authors found that PV is predominantly prevalent in middle-aged women (mean age 43 years), which accounts for 86.6% of the study group patients. Among the cohort of 135 patients, the authors found that 83.7% had hypochromic microcytic anemia, and among them, 5 patients reported a CD diagnosis [19].

In Romania, the prevalence of PV syndrome is still unknown. In the paper by Maruntelul et al., while assessing the prevalence of HLA genotypes in CD patients and their first-degree relatives, the authors found no cases of PV syndrome in the cohort of CD patients: 117 cases, predominantly female patients (79.5%), with a median age of 37 yrs, and anemia (53%). Therefore, PV syndrome is a rare finding in the Romanian adult CD population [20].

CD has traditionally been identified in children and young adults; however, recent years have seen an increase in detection among the older population, with similar trends for PV syndrome [1,16]. In the paper by Harmouch et al., the authors reported the case of PV syndrome in an 88-year-old female patient with a history of reflux disease, cognitive impairment, and allergies. She presented with difficulty in swallowing solid foods. Dysphagia may be more difficult to interpret among elderly, malnourished, and frail patients with multiple comorbidities, such as neurological, psychiatric, or cardiovascular problems [21].

The diagnosis of PV syndrome is usually endoscopic or radiologic. When a suspected esophageal web is present, barium swallow radiography is the most frequently requested investigation [21]. Compared to endoscopic examination, it has a few benefits. It is not only time-honored but is also more readily accessible in remote areas and can be interpreted by a radiologist or clinician without any prerequisite training or expertise [22]. Individuals suspected of having an esophageal web require extremely careful endoscopic examination, ideally under sedation or anesthesia. These webs are exceedingly thin and situated near the upper esophageal sphincter in the esophagus. This region is frequently traversed at a rapid pace, and as a result, it is frequently overlooked during esophagoscopy [23]. As a result, the endoscopist may rupture the esophageal web during the endoscope’s transit if they are unaware of it. A small quantity of bleeding at the site of the esophageal web may be misinterpreted by the endoscopist as mucosal irregularity caused by esophageal carcinoma in the event of an unintended rupture of a web [23,24,25].

The case we presented illustrates perfectly the classical features of PV syndrome in a middle-aged female patient who had longstanding iron-deficiency anemia treated by oral supplementation with no clinical remission. The patient was referred to the gastroenterology department only after dysphagia occurred. An earlier diagnosis of CD and treatment (and implementation of a gluten-free diet) in conjunction with iron supplementation may have reduced the risk of progressing towards PV syndrome. It is difficult to state that anemia secondary to CD is a risk factor for PV syndrome’s occurrence or that PV syndrome is a complication or progressive state of a long-standing undiagnosed CD. Interestingly, iron deficiency may not act alone but could be accompanied by other vitamin and micronutrient deficits, yet no corroborating evidence is currently available. Our patient developed clinical features of chronic anemia (cheilitis, glossitis, pallor), yet the loss of teeth could be secondary to other undocumented causes such as periodontal disease and bone frailty, but this is difficult to interpret as the patient did not benefit from a specialized consultation.

Similar findings were reported by Hefaiedh et al., where the authors reported the cases of two patients, a 61-year-old female patient and a 40-year-old male patient, respectively, with a history of difficulty swallowing and weight loss. Both of the patients had iron-deficiency anemia. After a thorough evaluation, celiac serology was performed, and a diagnosis of CD was made. The cases presented required endoscopic dilation, and a favorable outcome was attained [26]. Issa et al. reported common features in a 26-year-old East African woman who presented long-lasting episodes of oropharyngeal dysphagia. The diagnosis of PV syndrome is secondary to iron-deficiency anemia induced by Helicobacter pylori infection. CD was ruled out by specific tests. The patient required multiple sessions of endoscopic dilation to reach a permeable lumen [27].

Interestingly, PV syndrome is associated with a higher risk of malignant transformation, yet the true risk is unknown. In some papers, PV progresses towards esophageal cancer in 3% to 30% of cases and is considered a precancerous lesion [28]. In the study by Patil et al., the authors included 132 patients with a mean age of 43.5 who were assessed over 10 years. Among them, four patients had concomitant squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus along with the esophageal web. The authors reported an overall risk of 4.5% of progressing towards upper digestive malignancy. Interestingly, none of the patients had any other risk factors for esophageal malignancy, except for PV syndrome [29]. Therefore, endoscopic surveillance is advised, but there is no exact guideline recommendations available regarding the screening intervals [30].

In early PV syndrome, the treatment of iron-deficiency anemia is recommended. In more advanced diseases, endoscopic dilation treatment using balloons or Savary–Gilliard dilators is required. A successful dilation procedure should imply a small amount of fresh blood at the site of the web formation. Even though it is considered a safe procedure, esophageal perforation is possible in a very small number of cases [31].

4. Conclusions

The case presented highlights the necessity of screening for CD in patients with PV syndrome. Iron-deficiency anemia is an important risk factor for PV syndrome and a solid indicator to screen for CD even in the absence of typical symptoms of malabsorption. Patients presenting with PVs should undergo small intestine biopsies. Although PV syndrome is considered a preneoplastic condition, no surveillance strategies are currently implemented. A small proportion of patients will require repeated endoscopic treatment using balloons or buggies to achieve permeability, yet no differences between the two techniques have been reported to date.

Author Contributions

All authors—literature research; A.P. and I.C.—conceptualization; R.N. and C.M. writing the original draft; I.A.C. and I.-M.C.—review; G.A.C. and G.B.—editing. AAll authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (protocol code 12 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rubio-Tapia, A.; Hill, I.; Semrad, C.; Kelly, C.; Greer, K.; Limketkai, B.N.; Lebwohl, B. American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines Update: Diagnosis and Management of Celiac Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 118, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, A.; Bakshi, S.S.; Soni, N.; Chhavi, N. Iron deficiency anemia and Plummer-Vinson syndrome: Current insights. J. Blood Med. 2017, 8, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plummer, H. Diffuse dilatation of the esophagus without anatomic stenosis (cardiospasm): A report of 91 cases. JAMA 1912, 58, 2013–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinson, P. A case of cardiospasm with dilatation and angulation of the esophagus. Med. Clin. N. Am. 1919, 3, 623–627. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, A. Spasm at the entrance of the esophagus. J. Laryngol. Rhinol. Otol. 1919, 34, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, D. Clinical type of dysphagia. J. Laryngol. Rhinol. Otol. 1919, 34, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaris, A.; Alamri, G.A.; Kurdi, A.M.; Mallisho, A.; Al Awaji, N. Could Plummer-Vinson Syndrome Be Associated with Celiac Disease? Int. Med. Case Rep. J. 2023, 16, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, P.; Munisamy, M.; Selvan, K.S.; Hamide, A. Esophageal squamous cell cancer in Plummer-Vinson syndrome: Is lichen planus a missing link? J. Postgrad. Med. 2022, 68, 98–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novacek, G. Plummer-Vinson syndrome. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2006, 1, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broco Fernández, C.; Dominguez Carbajo, A.B.; Vivas Alegre, S.; Patiño Delgadillo, V.; Alcoba Vega, L.; Jorquera Plaza, F. Plummer-Vinson syndrome: Is the immune system the missing piece? Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Mukherjee, S. Plummer-Vinson Syndrome; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fall, F.; Gning, S.B.; Ndiaye, A.R.; Ndiaye, B.; Diagne-Guèye, N.-M.; Diallo, I.; Diédhiou, I.; Sarr, A.; Fall, B.; Soko, T.-O.; et al. The Plummer-Vinson syndrome: A retrospective study of 50 cases. J. Afr. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2011, 5, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefaiedh, R.; Boutreaa, Y.; Ouakaa-Kchaou, A.; Gargouri, D.; Elloumi, H.; Kochlef, A.; Romani, M.; Kilani, A.; Kharrat, J.; Ghorbel, A. Plummer Vinson syndrome. Tunis. Med. 2010, 88, 721–724. [Google Scholar]

- Yazaki, E.; Sifrim, D. Anatomy and physiology of the esophageal body. Dis. Esophagus 2012, 25, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Eckardt, A.J.; Fisseler-Eckhoff, A.; Haas, S.; Gockel, I.; Wehrmann, T. Endoscopic findings in patients with Schatzki rings: Evidence for an association with eosinophilic esophagitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 6960–6966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltesz, K.; Mosebach, J.; Paruch, E.; Covino, J. Updates on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. J. Am. Acad. Physician Assist. 2022, 35, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Gamra, O.; Mbarek, C.; Mouna, C.; Zribi, S.; Zainine, R.; Hariga, I.; El Khedim, A. Plummer Vinson syndrome. Tunis. Med. 2007, 85, 402–404. [Google Scholar]

- de la Rosa Mordán, Y.; Rodrigo García, G.; Miranda Cid, C.; Alonso Pérez, N. Dysphagia and Anemia. Plummer-Vinson syndrome. An. Pediatr. 2019, 90, 321–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakari, G.; Benelbarhdadi, I.; Bahije, L.; El Feydi Essaid, A. Endoscopic treatment of 135 cases of Plummer-Vinson web: A pilot experience. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2014, 80, 738–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruntelu, I.; Preda, C.M.; Sandra, I.; Istratescu, D.; Chifulescu, A.E.; Manuc, M.; Diculescu, M.; Talangescu, A.; Tugui, L.; Manuc, T.; et al. HLA Genotyping in Romanian Adult Patients with Celiac Disease, their First-Degree Relatives and Healthy Persons. J. Gastrointestin. Liver Dis. 2022, 31, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmouch, F.; Liaquat, H.; Chaput, K.J.; Geme, B. Plummer-Vinson Syndrome: A Rare Cause of Dysphagia in an Octogenarian. Am. J. Case Rep. 2021, 22, e929899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, J.F.; Lerner, A. Plummer-Vinson syndrome in primary Sjögren syndrome: A case-based review. Immunol. Res. 2022, 70, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binet, Q.; Delorme, A. Plummer-Vinson Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 652–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.B.; Albano, J.; Sandhu, N.; Candelario, N. Plummer-Vinson syndrome: Improving outcomes with a multidisciplinary approach. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2019, 12, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, S.S. Plummer-Vinson Syndrome. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016, 91, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hefaiedh, R.; Boutreaa, Y.; Ouakaa-Kchaou, A.; Kochlef, A.; Elloumi, H.; Gargouri, D.; Kharrat, J.; Ghorbel, A. Plummer Vinson syndrome association with coeliac disease. Arab. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 14, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issa, J.; Nassani, N.; Bazerbachi, F. A Chain Reaction to Dysphagia. Gastroenterology 2024, 166, 252–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhonda, K.Y.; Odze, R.O. Neoplasic precursor lesions of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Diagn. Histopathol. 2008, 14, 437–452. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, M.; Malipatel, R.; Devarbhavi, H. Plummer-Vinson syndrome: A decade’s experience of 132 cases from a single center. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 36, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.; Holloway, R.H.; Nguyen, N.Q. Current and future techniques in the evaluation of dysphagia. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 27, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahajwani, P.; Rustagi, M.; Tetarbe, S.; Shah, I. Plummer-Vinson Syndrome and Role of Endoscopic Balloon Dilatation in a 4-Year-Old Child. JPGN Rep. 2023, 4, e375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).