Fifty Years of Development of the Skull Vibration-Induced Nystagmus Test

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Early Years

2.1. Clinical Findings in Humans

2.2. Animal Model

3. Years 1990–2000

Clinical Findings in Humans

4. Years 2001–2010

4.1. Clinical Findings

4.2. Animal Model

Australian Group(s)

5. From 2011 until Now

5.1. Clinical Findings

5.1.1. American Group(s)

5.1.2. French Group(s)

5.1.3. Chilean Group(s)

5.1.4. Chinese Group(s)

5.1.5. German Group (s)

5.1.6. Italian Group(s)

5.1.7. Japanese Group(s)

5.1.8. Portuguese Group(s)

5.1.9. Spanish Group(s)

5.1.10. South Korea Group(s)

5.2. Animal Models

6. Summary of the Agreement and International Consensus

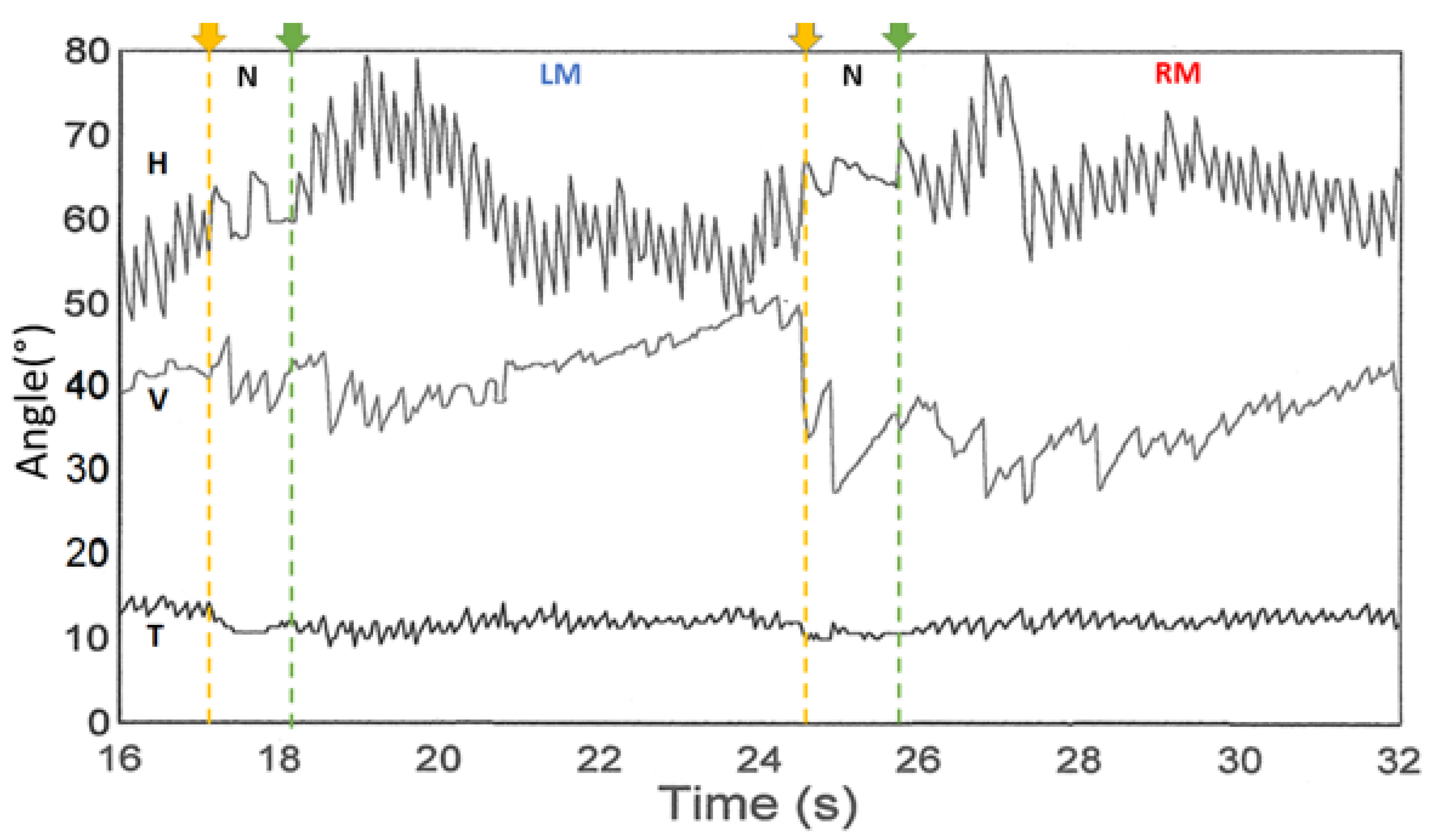

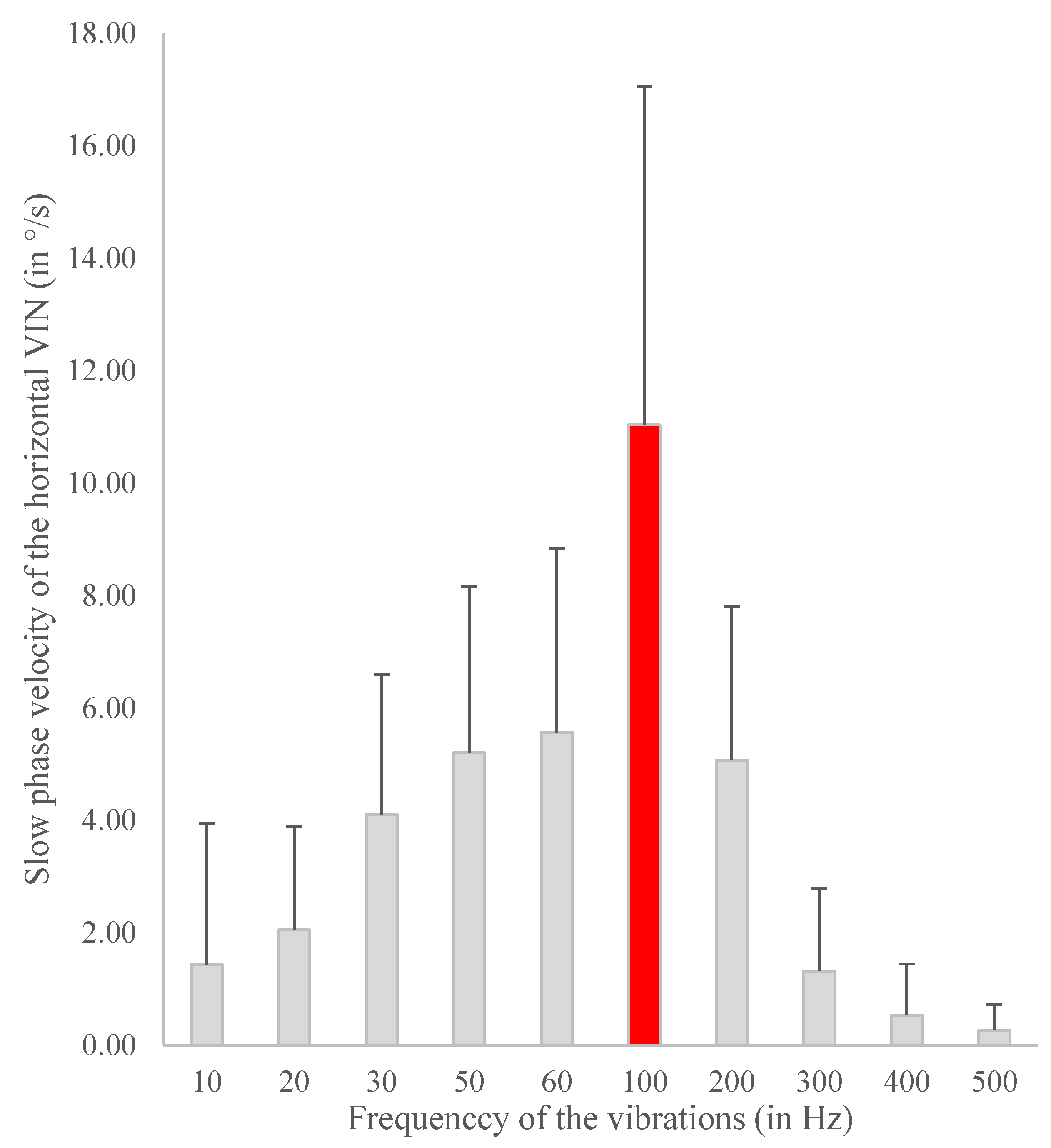

- Frequency consensus: 100 Hz widely used (majority of publications [3,4,7,10,16,24,25,30,31,34,40,45,46,47,49,52,54,56]). The systematic study of frequency optimization, analyzing SVIN SPV in response to 10 Hz up to 800 Hz, performed by Dumas et al. with the Mini-shaker device of B&K has confirmed this optimal frequency empirically accepted by many other authors [1,6] (Figure 2)

- Inner ear structure contribution to the constitution of the nystagmus (SVIN): the SCC and particularly the horizontal SCC is the predominant structure affected by the 100 Hz vibration. The vertical SCC are responsible for the vertical and torsional component. [14,40,60]. As for the otoliths, the utricle may contribute in a small proportion, and the saccule is more controversial [24,40,44,61].

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CaT | Caloric Test |

| MD | Menière’s disease |

| UVL | Unilateral vestibular lesion (PUVL = partial UVL, SUVL = severe UVL, TUVL = total UVL) |

| SCC | Semicircular canal |

| SVIN | Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus |

| SVINT | Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus Test |

| VN | Vestibular Neuritis |

| VS | Vestibular Schwannoma |

| VIN | Vibration Induced Nystagmus |

| VOR | Vestibulo Ocular Reflex |

References

- Dumas, G.; Tan, H.; Dumas, L.; Perrin, P.; Lion, A.; Schmerber, S. Skull vibration induced nystagmus in patients with superior semicircular canal dehiscence. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2019, 136, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumas, G.; Perrin, P.; Ouedraogo, E.; Schmerber, S. How to perform the skull vibration-induced nystagmus test (SVINT). Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2016, 133, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Lee, Y.; Park, M.; Kim, J.; Shin, J. Test-retest reliability of vibration-induced nystagmus in peripheral dizzy patients. J. Vestib. Res. 2010, 20, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohki, M.; Murofushi, T.; Nakahara, H.; Sugasawa, K. Vibration-Induced Nystagmus in Patients with Vestibular Disorders. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2003, 129, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, G.; Michel, J.; Lavieille, J.P.; Ouedraogo, E. [Semiologic value and optimum stimuli trial during the vibratory test: Results of a 3D analysis of nystagmus]. Ann. d’Otolaryngol. Chir. Cervico 2000, 117, 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, G.; Curthoys, I.S.; Lion, A.; Perrin, P.; Schmerber, S. The Skull Vibration-Induced Nystagmus Test of Vestibular Function—A Review. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yagi, T.; Ohyama, Y. Three-Dimensional Analysis of Nystagmus Induced by Neck Vibration. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 1996, 116, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, K.-F.; Schuster, E.-M. Vibration-Induced Nystagmus–A Sign of Unilateral Vestibular Deficit. ORL 1999, 61, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Békésy, G.V. Über akustische Reizung des Vestibularapparates. Pflüger Archiv Gesammte Physiologie Menschen Thiere 1935, 236, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lücke, K. [A vibratory stimulus of 100 Hz for provoking pathological nystagmus (author’s transl)]. Z. fur Laryngol. Rhinol. Otol. und Ihre Grenzgeb. 1973, 52, 716–720. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, D.; Michel, J.; Lavieille, J.; Charachon, R.; Ouedraogo, E. Clinical value of the cranial vibratory test. A 3D analysis of the nystagmus. J. Fr. D Otorhinolaryngol. Audiophonol. Chir. Maxillofac. Chir. Plast. De La Face 1999, 48, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, G.; De Waele, C.; Hamann, K.; Cohen, B.; Negrevergne, M.; Ulmer, E.; Schmerber, S. Le test vibratoire osseux vestibulaire. Ann. d’Otolaryngol. Chir. Cervico 2007, 124, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, G.; Perrin, P.; Schmerber, S. Nystagmus induced by high frequency vibrations of the skull in total unilateral peripheral vestibular lesions. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2008, 128, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, G.; Lion, A.; Karkas, A.; Perrin, P.; Perottino, F.; Schmerber, S. Skull vibration-induced nystagmus test in unilateral superior canal dehiscence and otosclerosis: A vestibular Weber test. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2014, 134, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumas, G.; Karkas, A.; Perrin, P.; Chahine, K.; Schmerber, S. High-Frequency Skull Vibration-Induced Nystagmus Test in Partial Vestibular Lesions. Otol. Neurotol. 2011, 32, 1291–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuti, D.; Mandalà, M. Sensitivity and specificity of mastoid vibration test in detection of effects of vestibular neuritis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2005, 25, 271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Hamann, K.-F. Vibration-Induced Nystagmus: A Biomarker for Vestibular Deficits-A Synopsis. ORL 2017, 79, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombé, C. The Skull Vibration–Induced Nystagmus Test as Vestibular Examination in Children with Sensorineural Hearing Loss; University of Grenoble: Saint-Martin-d’Hères, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lackner, J.R.; Graybiel, A. Elicitation of vestibular side effects by regional vibration of the head. Aerosp. Med. 1974, 45, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Yagi, T.; Kamio, T. The Role of Cervical Inputs in Compensation of Unilateral Labyrinthectomized Patients. Clin. Test. Vestib. Syst. 1988, 42, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, E.; Fernández, C.; Goldberg, J.M. Responses of Squirrel Monkey Vestibular Neurons to Audio-Frequency Sound and Head Vibration. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 1977, 84, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J. Nystagmus de Vibration de Hamann. J. Fr. d’oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 1995, 44, 339–341. [Google Scholar]

- Strupp, M.; Arbusow, V.; Dieterich, M.; Sautier, W.; Brandt, T. Perceptual and oculomotor effects of neck muscle vibration in vestibular neuritis. Ipsilateral somatosensory substitution of vestibular function. Brain 1998, 121, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlberg, M.; Aw, S.T.; Black, R.A.; Todd, M.J.; MacDougall, H.; Halmagyi, G.M. Vibration-induced ocular torsion and nystagmus after unilateral vestibular deafferentation. Brain 2003, 126, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.A.; Hughes, G.B.; Ruggieri, P.N. Vibration-Induced Nystagmus as an Office Procedure for the Diagnosis of Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence. Otol. Neurotol. 2007, 28, 911–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumas, G.; Perrin, P.; Morel, N.; N’Guyen, D.Q.; Schmerber, S. Le test vibratoire osseux crânien dans les lésions vestibu-laires périphériques partielles-Influence de la fréquence du stimulus sur le sens du nystagmus. Rev. Laryngol. Otol. Rhinol. 2005, 126, 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Boniver, R. Vibration-induced nystagmus. B ENT 2008, 4, 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, J.; Lavieille, G.; Schmerber, J.; Sauvag, S. Le Test Vibratoire Osseux Crânien. Rev. SFORL 2004, 82, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, J.; Dumas, G.; Lavieille, J.P.; Charachon, R. Diagnostic value of vibration-induced nystagmus obtained by com-bined vibratory stimulation applied to the neck muscles and skull of 300 vertiginous patients. Rev. Laryngol. Otol. Rhinol. 2001, 122, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ulmer, E.; Chays, A.; Bremond, E.G. Nystagmus induit par des vibrations: Physiopathogénie et intérêt en clinique. Ann. d’Otolaryngol. Chir. Cervico 2004, 121, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzari, L.; Modugno, G.C.; Brandolini, C.; Pirodda, A. Bone Vibration-Induced Nystagmus Is Useful in Diagnosing Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence. Audiol. Neurotol. 2008, 13, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzari, L.; Modugno, G.C. Nystagmus induced by bone (mastoid) vibration in otosclerosis: A new perspective in the study of vestibular function in otosclerosis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2008, 14, CR505–CR510. [Google Scholar]

- Modugno, G.; Brandolini, G.; Piras, C.; Raimondi, G.; Ferr, M. Bone Vibration-Induced Nystagmus (VIN) Is Useful in Diag-nosing Vestibular Schwannoma (VS). In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Acoustic Neuroma, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 28 June–1 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, N. Vibration induced nystagmus in normal subjects and in patients with dizziness. A videonystagmography study. Rev. de Laryngol.-Otol.-Rhinol. 2003, 124, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson, M.; Andersson, G.; Gomez, S.; Johansson, R.; Mårtensson, A.; Karlberg, M.; Fransson, P.-A. Cervical muscle afferents play a dominant role over vestibular afferents during bilateral vibration of neck muscles. J. Vestib. Res. 2006, 16, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curthoys, I.S.; MacDougall, H.; Vidal, P.-P.; De Waele, C. Sustained and Transient Vestibular Systems: A Physiological Basis for Interpreting Vestibular Function. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Curthoys, I.S.; Kim, J.; McPhedran, S.K.; Camp, A.J. Bone conducted vibration selectively activates irregular primary otolithic vestibular neurons in the guinea pig. Exp. Brain Res. 2006, 175, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curthoys, I.S.; Vulovic, V.; Burgess, A.M.; Manzari, L.; Sokolic, L.; Pogson, J.; Robins, M.; Mezey, E.L.; Goonetilleke, S.; Cornell, E.D.; et al. Neural basis of new clinical vestibular tests: Otolithic neural responses to sound and vibration. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2014, 41, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, J.; Krakovitz, P. Nystagmus in Enlarged Vestibular Aqueduct: A Case Series. Audiol. Res. 2015, 5, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Soper, J.; Lohse, C.M.; Eggers, S.D.; Kaufman, K.R.; McCaslin, D.L. Agreement between the Skull Vibration-Induced Nystagmus Test and Semicircular Canal and Otolith Asymmetry. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2021, 32, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Mukherjee, M.; Stergiou, N.; Chien, J.H. Using mastoid vibration can detect the uni/bilateral vestibular deterioration by aging during standing. J. Vestib. Res. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumas, G.; Lion, A.; Gauchard, G.C.; Herpin, G.; Magnusson, M.; Perrin, P.P. Clinical interest of postural and vestibulo-ocular reflex changes induced by cervical muscles and skull vibration in compensated unilateral vestibular lesion patients. J. Vestib. Res. 2013, 23, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinno, S.; Perrin, P.; Abouchacra, K.S.; Dumas, G. The skull vibration-induced nystagmus test: A useful vestibular screening test in children with hearing loss. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2020, 137, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumas, G.; Fabre, C.; Charpiot, A.; Fath, L.; Chaney-Vuong, H.; Perrin, P.; Schmerber, S. Skull Vibration-Induced Nystagmus Test in a Human Model of Horizontal Canal Plugging. Audiol. Res. 2021, 11, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waissbluth, S.; Sepúlveda, V. The Skull Vibration-induced Nystagmus Test (SVINT) for Vestibular Disorders. Otol. Neurotol. 2021, 42, 646–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, S.; Guo, J.; Wu, Z.; Qiang, D.; Huang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Yao, Q.; Chen, S.; Tian, D. Vibration-Induced Nystagmus in Patients with Unilateral Peripheral Vestibular Disorders. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2013, 65, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teggi, R.; Battista, R.A.; Di Berardino, F.; Familiari, M.; Cangiano, I.; Gatti, O.; Bussi, M. Evaluation of a large cohort of adult patients with Ménière’s disease: Bedside and clinical history. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2020, 40, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teggi, R.; Familiari, M.; Gatti, O.; Bussi, M. Vertigo without cochlear symptoms: Vestibular migraine or Menière disease? Neurol. Sci. 2021, 42, 5071–5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, C.; Kawahara, T.; Yagi, M.; Murofushi, T. Association between vestibular dysfunction and findings of horizontal head-shaking and vibration-induced nystagmus. J. Vestib. Res. 2020, 30, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, R.; Navarro, M.; Pérez-Guillén, V.; Pérez-Garrigues, H. The role of vertical semicircular canal function in the vertical component of skull vibration-induced nystagmus. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2020, 140, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gammara, V. Comportamiento del Nistagmus Inducido por Vibración (VIN) en Pacientes con Patología Vestibular Definida. 2018. Available online: https://trobes.uv.es/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma991009434269806258&context=L&vid=34CVA_UV:VU1&lang=ca&search_scope=cataleg_UV&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=Cataleg&query=title,contains,Comportamiento%20del%20Nistagmus%20Inducido%20por%20Vibraci%C3%B3n%20 (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Martin-Sanz, E.; Esteban-Sánchez, J.; González-Márquez, R.; Larrán-Jiménez, A.; Cuesta, Á.; Batuecas-Caletrio, Á. Vibration-induced nystagmus and head impulse test screening for vestibular schwannoma. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2021, 141, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batuecas-Caletrío, A.; Martínez-Carranza, R.; Nuñez, G.M.G.; Nava, M.J.F.; Gómez, H.S.; Ruiz, S.S.; Guillén, V.P.; Pérez-Fernández, N. Skull vibration-induced nystagmus in vestibular neuritis. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2020, 140, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, E.G.; Araújo, P.E.-S.; Guillén, V.P.; Gamarra, M.F.V.; Ferrer, V.F.; Rauch, M.C.; Garrigues, H.P. Parameters of skull vibration-induced nystagmus in normal subjects. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2018, 275, 1955–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, J.-W.; Kim, J.-S.; Hong, S.K. Vibration-Induced Nystagmus after Acute Peripheral Vestibular Loss. Otol. Neurotol. 2011, 32, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.M.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, J.W.; Shim, D.B.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.H. Vibration-induced nystagmus in patients with vestibular schwannoma: Characteristics and clinical implications. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2017, 128, 1372–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, G.; Lion, A.; Perrin, P.; Ouedraogo, E.; Schmerber, S. Topographic analysis of the skull vibration-induced nystagmus test with piezoelectric accelerometers and force sensors. NeuroReport 2016, 27, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vulovic, V.; Curthoys, I.S. Bone conducted vibration activates the vestibulo-ocular reflex in the guinea pig. Brain Res. Bull. 2011, 86, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dlugaiczyk, J.; Burgess, A.M.; Curthoys, I.S. Activation of Guinea Pig Irregular Semicircular Canal Afferents by 100 Hz Vibration: Clinical Implications for Vibration-induced Nystagmus and Vestibular-evoked Myogenic Potentials. Otol. Neurotol. 2020, 41, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curthoys, I.S. The Neural Basis of Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus (SVIN). Audiol. Res. 2021, 11, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabre, C.; Tan, H.; Dumas, G.; Giraud, L.; Perrin, P.; Schmerber, S. Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus Test: Correlations with Semicircular Canal and Otolith Asymmetries. Audiol. Res. 2021, 11, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georges, D. Stimulation with the Minishaker (Bruel Kjaer (B&K), Naerum, the Netherlands. In Proceedings of the Congress of the AAO-HNS New Orleans 2019, New Orleans, LA, USA, 16–18 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Curthoys, I.S.; Vulovic, V.; Burgess, A.M.; Sokolic, L.; Goonetilleke, S.C. The response of guinea pig primary utricular and saccular irregular neurons to bone-conducted vibration (BCV) and air-conducted sound (ACS). Hear. Res. 2016, 331, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curthoys, I.S.; Grant, J.W. How does high-frequency sound or vibration activate vestibular receptors? Exp. Brain Res. 2015, 233, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| French Group(s) | German Group(s) | Japanese Group(s) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Australian Group(s) | Karlberg et al. (2003) used scleral coils to analyze 3D VIN at 92 Hz in patients with UVL (neurotomies, neuritis). They inferred that this nystagmus was secondary to an otolithic lesion or superior SCC implication [24]. The author suggested that the displacement of the SVH was secondary to a damage to the otolithic organ or superior SCC inducing an eye torsion. |

| American Group(s) | White et al. in 2007 described in eight patients with SSCD a down beating and torsional nystagmus induced by cranial vibration suggesting a direct stimulation of the dehiscent SCC [25]. |

| Belgian Group(s) | In 2008, Boniver hypothesized that SVINT was the result of altered proprioceptive inputs to neck muscles or direct stimulation of vestibular receptors in the intact labyrinth after unilateral vestibular deafferentation [27]. |

| French Group(s) | Dumas et al. published a report on the value of this test in clinical practice and recalled its fundamental bases [28]. Those clinical results were then presented at the Barany Society in Paris in 2004 and published in the special issue devoted to this society by the journal of vestibular research in 2004 [28]. Dumas et al. published in 2005 a series of partial vestibular lesions, signaling the interest and influence of stimulus frequency on the VIN and reporting for the first time in an article a SVIN in SSCD with a vertical but also a horizontal component [26]. Michel et al. reported the use of a 50 Hz (alleged frequency) vibrator in patients with confirmed MD. They assumed that VIN can be provoked by both the labyrinth and the neck muscle stimulations [29]. In 2004, Ulmer et al. provided additional information on the mechanisms involved by SVINT in case of UVL [30]. First, the vibrations of the skull selectively stimulated type I hair cells. Second, the direction of the beat of the nystagmus was toward the intact side/ear. They finally suggested that the vibrator excited both sides simultaneously, which suggested the primarily role of the intact side to provide the nystagmus, which reveals a vestibular asymmetry. |

| Italian Group(s) | Nuti and Mandala in 2005 studied the sensitivity and specificity of the mastoid vibration test in patients with VN using a handheld (Adele international Bologna Italy) battery powered device at 100 Hz. They concluded that the test had a sensitivity of 75% and specificity of 100%, and that the sensitivity of the test increased with increasing severity of the vestibular lesion and was well correlated with caloric paresis [16]. During the years 2008 and 2009, Manzari published articles in which he assessed different groups of patients and concluded that SVINT was useful in diagnosing SSCD, and in patients with otosclerosis (long stimulation of 40 s) with conductive hearing loss, it may be appropriate to evaluate the vestibular function. In SSCD cases, considering that the nystagmus was mainly rotatory or vertical, he hypothesized that it was in relation with the stimulation of the affected superior SCC and in otosclerosis, he hypothesized the horizontal nystagmus was linked to the ampullifugal/ampullipetal flow in lateral SCCs [31,32]. Modugno et al. in observed a positive SVIN in 44% of cases of the 86 schwannomas and a VIN beating ipsilaterally in 27% of cases [33]. |

| Japanese Group(s) | Ohki in 2003 [4] studied the VIN obtained after mastoid and frontal stimulations in patients with a UVL and compared it to the results of CaT and cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potential (cVEMP). This author demonstrated that the existence of a VIN with a dominant horizontal component, especially during mastoid stimulation beating toward the healthy side, was correlated with caloric unilateral weakness (when hypofunction was greater than 50%; a VIN was present in 90% of cases). He found no correlation with cVEMP. |

| Spanish Group(s) | In 2003, Perez published an article using a mini muscle massager and concluded that the value of the slow phase velocity (SPV) of vibration-induced nystagmus could be used to identify a sizeable proportion of patients with a vestibular disorder. In case of spontaneous nystagmus, the skull vibration enhanced the nystagmus SPV by 1.5 to twice the initial velocity [34]. |

| Swedish Group(s) | Magnusson et al. demonstrated that during bilateral vibration of neck muscles in normal subjects for posturographic recordings cervical muscle afferents played a dominant role over vestibular afferents, but they did not analyze concomitantly the SVIN [35]. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sinno, S.; Schmerber, S.; Perrin, P.; Dumas, G. Fifty Years of Development of the Skull Vibration-Induced Nystagmus Test. Audiol. Res. 2022, 12, 10-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres12010002

Sinno S, Schmerber S, Perrin P, Dumas G. Fifty Years of Development of the Skull Vibration-Induced Nystagmus Test. Audiology Research. 2022; 12(1):10-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres12010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleSinno, Solara, Sébastien Schmerber, Philippe Perrin, and Georges Dumas. 2022. "Fifty Years of Development of the Skull Vibration-Induced Nystagmus Test" Audiology Research 12, no. 1: 10-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres12010002

APA StyleSinno, S., Schmerber, S., Perrin, P., & Dumas, G. (2022). Fifty Years of Development of the Skull Vibration-Induced Nystagmus Test. Audiology Research, 12(1), 10-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres12010002