Hyperlipidemia and Obesity’s Role in Immune Dysregulation Underlying the Severity of COVID-19 Infection

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

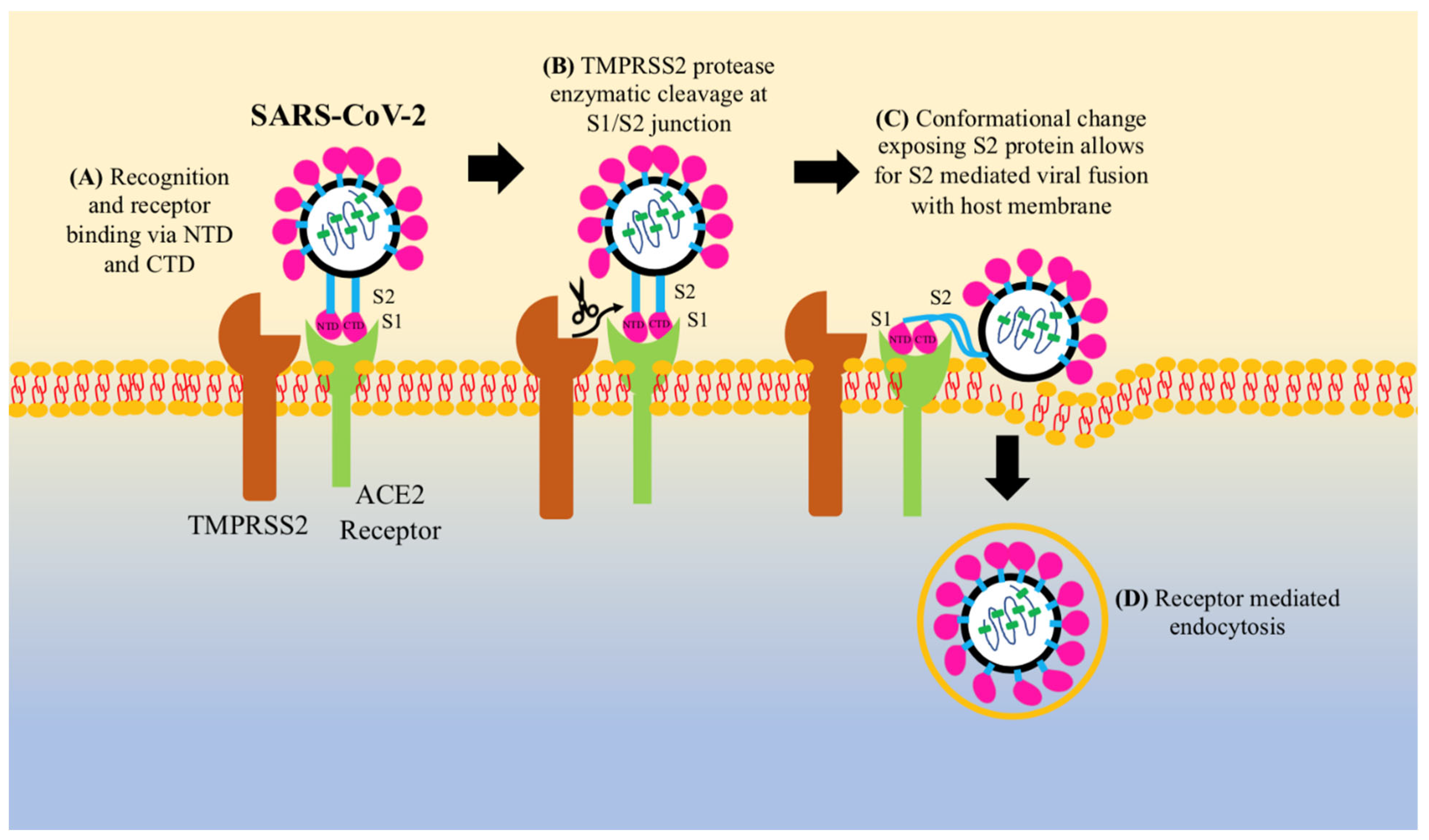

3. Pathogenesis of COVID-19

4. Cholesterol’s Role in COVID-19 Pathogenesis

5. Obesity and SARS-CoV-2 Infection

6. Vitamin D and COVID-19

7. GSH and COVID-19

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Nishiura, H.; Linton, N.M.; Akhmetzhanov, A.R. Initial Cluster of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Infections in Wuhan, China Is Consistent with Substantial Human-to-Human Transmission. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sajjad, H.; Majeed, M.; Imtiaz, S.; Siddiqah, M.; Sajjad, A.; Din, M.; Ali, M. Origin, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment Options for SARS-CoV-2: A Review. Biologia 2021, 76, 2655–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esakandari, H.; Nabi-Afjadi, M.; Fakkari-Afjadi, J.; Farahmandian, N.; Miresmaeili, S.-M.; Bahreini, E. A comprehensive review of COVID-19 characteristics. Biol. Proced. Online 2020, 22, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, P. The role of adipokines in chronic inflammation. Immunotargets Ther. 2016, 5, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Klop, B.; Elte, J.W.; Cabezas, M.C. Dyslipidemia in obesity: Mechanisms and potential targets. Nutrients 2013, 5, 1218–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsoupras, A.; Lordan, R.; Zabetakis, I. Inflammation, not Cholesterol, Is a Cause of Chronic Disease. Nutrients 2018, 10, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Obesity and Overweight. 9 June 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Boden, G. Obesity and free fatty acids. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 37, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feingold, K.R. Obesity and Dyslipidemia. In Endotext; Feingold, K.R., Ed.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmani-Kukia, N.; Abbasi, A. Physiological and Immunological Causes of the Susceptibility of Chronic Inflammatory Patients to COVID-19 Infection: Focus on Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 576412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T.; Namkoong, H. Susceptibility of the obese population to COVID-19. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 101, 380–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ling, H.; Huang, X.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Yi, C.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, Y.; He, Y.; Deng, S.; et al. Potential spreading risks and disinfection challenges of medical wastewater by the presence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral RNA in septic tanks of Fangcang Hospital. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Du, G. COVID-19 may transmit through aerosol. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 189, 1143–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- van Doremalen, N.; Bushmaker, T.; Morris, D.H.; Holbrook, M.G.; Gamble, A.; Williamson, B.N.; Tamin, A.; Harcourt, J.L.; Thornburg, N.J.; Gerber, S.I.; et al. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1564–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.-M.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.-G.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.-W.; Tian, J.-H.; Pei, Y.-Y.; et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peng, G.; Sun, D.; Rajashankar, K.R.; Qian, Z.; Holmes, K.V.; Li, F. Crystal structure of mouse coronavirus receptor-binding domain complexed with its murine receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 10696–10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Supekar, V.M.; Bruckmann, C.; Ingallinella, P.; Bianchi, E.; Pessi, A.; Carfí, A. Structure of a proteolytically resistant core from the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus S2 fusion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 17958–17963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, A.; Peng, Y.; Huang, B.; Ding, X.; Wang, X.; Niu, P.; Meng, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; et al. Genome Composition and Divergence of the Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Originating in China. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hatmal, M.M.; Alshaer, W.; Al-Hatamleh, M.A.I.; Hatmal, M.; Smadi, O.; Taha, M.O.; Oweida, A.J.; Boer, J.C.; Mohamud, R.; Plebanski, M. Comprehensive Structural and Molecular Comparison of Spike Proteins of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, and Their Interactions with ACE2. Cells 2020, 9, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Tao, H.; Yan, Y.; Huang, S.-Y.; Xiao, Y. Molecular Mechanism of Evolution and Human Infection with SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 2020, 12, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shang, J.; Wan, Y.; Luo, C.; Ye, G.; Geng, Q.; Auerbach, A.; Li, F. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11727–11734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosillo, N.; Viceconte, G.; Ergonul, O.; Ippolito, G.; Petersen, E. COVID-19, SARS and MERS: Are they closely related? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, R.; Romero-Severson, E.; Sanche, S.; Hengartner, N. Estimating the reproductive number R0 of SARS-CoV-2 in the United States and eight European countries and implications for vaccination. J. Theor. Biol. 2021, 517, 110621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Lagniton, P.N.; Ye, S.; Li, E.; Xu, R.-H. COVID-19: What has been learned and to be learned about the novel coronavirus disease. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1753–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letko, M.; Marzi, A.; Munster, V. Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ziegler, C.G.K.; Allon, S.J.; Nyquist, S.K.; Mbano, I.M.; Miao, V.N.; Tzouanas, C.N.; Cao, Y.; Yousif, A.S.; Bals, J.; Hauser, B.M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues. Cell 2020, 181, 1016–1035.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Pöhlmann, S. A Multibasic Cleavage Site in the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2 Is Essential for Infection of Human Lung Cells. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 779–784.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, E.; Sauter, D. Furin-mediated protein processing in infectious diseases and cancer. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2019, 8, e1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Izaguirre, G. The proteolytic regulation of virus cell entry by furin and other proprotein convertases. Viruses 2019, 11, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simmons, G.; Gosalia, D.N.; Rennekamp, A.J.; Reeves, J.D.; Diamond, S.L.; Bates, P. Inhibitors of cathepsin L prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11876–11881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, M.-M.; Yang, W.-L.; Yang, F.-Y.; Zhang, L.; Huang, W.-J.; Hou, W.; Fan, C.-F.; Jin, R.-H.; Feng, Y.-M.; Wang, Y.-C.; et al. Cathepsin L plays a key role in SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans and humanized mice and is a promising target for new drug development. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirato, K.; Kawase, M.; Matsuyama, S. Wild-type human coronaviruses prefer cell-surface TMPRSS2 to endosomal cathepsins for cell entry. Virology 2018, 517, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantuti-Castelvetri, L.; Ojha, R.; Pedro, L.D.; Djannatian, M.; Franz, J.; Kuivanen, S.; Kallio, K.; Kaya, T.; Anastasina, M.; Smura, T.; et al. Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and provides a possible pathway into the central nervous system. BioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayati, A.; Kumar, R.; Francis, V.; McPherson, P.S. SARS-CoV-2 infects cells following viral entry via clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Qi, J.; Gao, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Bao, J.; et al. Molecular basis of binding between novel human coronavirus MERS-CoV and its receptor CD26. Nature 2013, 500, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abu-Farha, M.; Thanaraj, T.A.; Qaddoumi, M.G.; Hashem, A.; Abubaker, J.; Al-Mulla, F. The Role of Lipid Metabolism in COVID-19 Virus Infection and as a Drug Target. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caterino, M.; Gelzo, M.; Sol, S.; Fedele, R.; Annunziata, A.; Calabrese, C.; Fiorentino, G.; D’Abbraccio, M.; Dell’Isola, C.; Fusco, F.M.; et al. Dysregulation of lipid metabolism and pathological inflammation in patients with COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardacci, R.; Colavita, F.; Castilletti, C.; Lapa, D.; Matusali, G.; Meschi, S.; del Nonno, F.; Colombo, D.; Capobianchi, M.R.; Zumla, A.; et al. Evidences for lipid involvement in SARS-CoV-2 cytopathogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, S.S.G.; Soares, V.C.; Ferreira, A.C.; Sacramento, C.Q.; Fintelman-Rodrigues, N.; Temerozo, J.R.; Teixeira, L.; da Silva, M.A.N.; Barreto, E.; Mattos, M.; et al. Lipid droplets fuel SARS-CoV-2 replication and production of inflammatory mediators. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1009127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalakis, K.; Ilias, I. SARS-CoV-2 infection and obesity: Common inflammatory and metabolic aspects. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 469–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trayhurn, P. Hypoxia and adipocyte physiology: Implications for adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2014, 34, 207–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilias, I.; Jahaj, E.; Kokkoris, S.; Zervakis, D.; Temperikidis, P.; Magira, E.; Pratikaki, M.; Vassiliou, A.G.; Routsi, C.; Kotanidou, A.; et al. Clinical Study of Hyperglycemia and SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Intensive Care Unit Patients. In Vivo 2020, 34, 3029–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamagishi, S.-I.; Matsui, T. Role of Hyperglycemia-Induced Advanced Glycation End Product (AGE) Accumulation in Atherosclerosis. Ann. Vasc. Dis. 2018, 11, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cai, S.-H.; Liao, W.; Chen, S.-W.; Liu, L.-L.; Liu, S.-Y.; Zheng, Z.-D. Association between obesity and clinical prognosis in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Q.; Wei, W.-Q.; Chaugai, S.; Leon, B.G.C.; Mosley, J.D.; Leon, D.A.C.; Jiang, L.; Ihegword, A.; Shaffer, C.M.; Linton, M.F.; et al. Association Between Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels and Risk for Sepsis Among Patients Admitted to the Hospital With Infection. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e187223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kočar, E.; Režen, T.; Rozman, D. Cholesterol, lipoproteins, and COVID-19: Basic concepts and clinical applications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2021, 1866, 158849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirahanchi, Y.; Sinawe, H.; Dimri, M. Biochemistry, LDL Cholesterol. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Yuan, Z.; Pavel, M.A.; Jablonski, S.M.; Jablonski, J.; Hobson, R.; Valente, S.; Reddy, C.B.; Hansen, S.B. The role of high cholesterol in age-related COVID19 lethality. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, T.; Murakami, M. COVID-19: A New Virus, but a Familiar Receptor and Cytokine Release Syndrome. Immunity 2020, 52, 731–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojyo, S.; Uchida, M.; Tanaka, K.; Hasebe, R.; Tanaka, Y.; Murakami, M.; Hirano, T. How COVID-19 induces cytokine storm with high mortality. Inflamm. Regen. 2020, 40, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmudpour, M.; Roozbeh, J.; Keshavarz, M.; Farrokhi, S.; Nabipour, I. COVID-19 cytokine storm: The anger of inflammation. Cytokine 2020, 133, 155151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, H.; Kisugi, R. Mechanisms of LDL oxidation. Clin. Chim. Acta 2010, 411, 1875–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulthe, J.; Fagerberg, B. Circulating Oxidized LDL Is Associated With Subclinical Atherosclerosis Development and Inflammatory Cytokines (AIR Study). Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2002, 22, 1162–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ho, P.-C.; Chang, K.-C.; Chuang, Y.-S.; Wei, L.-N. Cholesterol regulation of receptor-interacting protein 140 via microRNA-33 in inflammatory cytokine production. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 1758–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Estruch, M.; Sanchez-Quesada, J.L.; Beloki, L.; Ordóñez-Llanos, J.; Benitez, S. The Induction of Cytokine Release in Monocytes by Electronegative Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) Is Related to Its Higher Ceramide Content than Native LDL. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 2601–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bailey, A.; Mohiuddin, S.S. Biochemistry, High Density Lipoprotein. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Masana, L.; Correig, E.; Ibarretxe, D.; Anoro, E.; Arroyo, J.A.; Jericó, C.; Guerrero, C.; Miret, M.; Näf, S.; Pardo, A.; et al. Low HDL and high triglycerides predict COVID-19 severity. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Dong, H.; Wu, C.; Wu, F.; Yu, B.; Lv, J.; Zhang, S.; Wu, G.; et al. Low high-density lipoprotein level is correlated with the severity of COVID-19 patients: An observational study. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Nardo, D.; Labzin, L.; Kono, H.; Seki, R.; Schmidt, S.V.; Beyer, M.; Xu, D.; Zimmer, S.; Lahrmann, C.; Schildberg, F.A.; et al. High-density lipoprotein mediates anti-inflammatory reprogramming of macrophages via the transcriptional regulator ATF3. Nat. Immunol. 2014, 15, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barter, P.J.; Nicholls, S.; Rye, K.-A.; Anantharamaiah, G.M.; Navab, M.; Fogelman, A.M. Antiinflammatory Properties of HDL. Circ. Res. 2004, 95, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unamuno, X.; Gómez-Ambrosi, J.; Rodríguez, A.; Becerril, S.; Frühbeck, G.; Catalán, V. Adipokine dysregulation and adipose tissue inflammation in human obesity. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 48, e12997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gomes, D.C.K.; Sichieri, R.; Junior, E.V.; Boccolini, C.S.; Souza, A.d.M.; Cunha, D.B. Trends in obesity prevalence among Brazilian adults from 2002 to 2013 by educational level. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koliaki, C.; Liatis, S.; Kokkinos, A. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: Revisiting an old relationship. Metabolism 2019, 92, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piche, M.E.; Tchernof, A.; Despres, J.P. Obesity Phenotypes, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Diseases. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1477–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murugan, A.T.; Sharma, G. Obesity and respiratory diseases. Chron. Respir. Dis. 2008, 5, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olson, N.C.; Cushman, M.; Lutsey, P.L.; McClure, L.A.; Judd, S.; Tracy, R.P.; Folsom, A.R.; Zakai, N.A. Inflammation markers and incident venous thromboembolism: The REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 12, 1993–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avgerinos, K.I.; Spyrou, N.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Dalamaga, M. Obesity and cancer risk: Emerging biological mechanisms and perspectives. Metabolism 2019, 92, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exley, M.A.; Hand, L.; O’Shea, D.; Lynch, L. Interplay between the immune system and adipose tissue in obesity. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 223, R41–R48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ritter, A.; Kreis, N.-N.; Louwen, F.; Yuan, J. Obesity and COVID-19: Molecular Mechanisms Linking both Pandemics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louwen, F.; Ritter, A.; Kreis, N.N.; Yuan, J. Insight into the development of obesity: Functional alterations of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 888–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, E.E.; Flier, J.S. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 2548–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhao, J.; Meng, H.; Zhang, X. Adipose Tissue-Resident Immune Cells in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, N.; Parker, J.L.; Lugus, J.J.; Walsh, K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumeng, C.N.; Bodzin, J.L.; Saltiel, A.R. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Winer, S.; Chan, Y.; Paltser, G.; Truong, D.; Tsui, H.; Bahrami, J.; Dorfman, R.; Wang, Y.; Zielenski, J.; Mastronardi, F.; et al. Normalization of obesity-associated insulin resistance through immunotherapy. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, T.; Ackerman, S.E.; Shen, L.; Engleman, E. Role of innate and adaptive immunity in obesity-associated metabolic disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esser, N.; L’Homme, L.; De Roover, A.; Kohnen, L.; Scheen, A.J.; Moutschen, M.; Piette, J.; Legrand-Poels, S.; Paquot, N. Obesity phenotype is related to NLRP3 inflammasome activity and immunological profile of visceral adipose tissue. Diabetologia 2013, 56, 2487–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vandanmagsar, B.; Youm, Y.-H.; Ravussin, A.; Galgani, J.E.; Stadler, K.; Mynatt, R.L.; Ravussin, E.; Stephens, J.M.; Dixit, V.D. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Vazquez, I.; Fernández-Veledo, S.; Krämer, D.K.; Vila, R.; García, L.; Lorenzo, M. Insulin resistance associated to obesity: The link TNF-alpha. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2008, 114, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, M.; Marette, A. Targeted disruption of inducible nitric oxide synthase protects against obesity-linked insulin resistance in muscle. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 1138–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savini, I.; Catani, M.V.; Evangelista, D.; Gasperi, V.; Avigliano, L. Obesity-Associated Oxidative Stress: Strategies Finalized to Improve Redox State. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 10497–10538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manna, P.; Jain, S.K. Obesity, Oxidative Stress, Adipose Tissue Dysfunction, and the Associated Health Risks: Causes and Therapeutic Strategies. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2015, 13, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flaherty, R.L.; Owen, M.; Fagan-Murphy, A.; Intabli, H.; Healy, D.; Patel, A.; Allen, M.C.; Patel, B.A.; Flint, M.S. Glucocorticoids induce production of reactive oxygen species/reactive nitrogen species and DNA damage through an iNOS mediated pathway in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2017, 19, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korakas, E.; Ikonomidis, I.; Kousathana, F.; Balampanis, K.; Kountouri, A.; Raptis, A.; Palaiodimou, L.; Kokkinos, A.; Lambadiari, V. Obesity and COVID-19: Immune and metabolic derangement as a possible link to adverse clinical outcomes. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2020, 319, E105–E109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coperchini, F.; Chiovato, L.; Croce, L.; Magri, F.; Rotondi, M. The cytokine storm in COVID-19: An overview of the involvement of the chemokine/chemokine-receptor system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020, 53, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, P. Obesity and lung inflammation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 108, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shore, S.A. Obesity, airway hyperresponsiveness, and inflammation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 108, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channappanavar, R.; Perlman, S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: Causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin. Immunopathol. 2017, 39, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwaifa, I.K.; Bahari, H.; Yong, Y.K.; Noor, S.M. Endothelial Dysfunction in Obesity-Induced Inflammation: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tabit, C.E.; Chung, W.B.; Hamburg, N.; Vita, J.A. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus: Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2010, 11, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kruglikov, I.L.; Scherer, P.E. The Role of Adipocytes and Adipocyte-Like Cells in the Severity of COVID-19 Infections. Obesity 2020, 28, 1187–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, L.; Balaji, K.S.; Wei, C.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Peng, J.; Fu, J. Expressions and significances of the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 gene, the receptor of SARS-CoV-2 for COVID-19. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 4383–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, Z.; Flammer, A.J.; Steiger, P.; Haberecker, M.; Andermatt, R.; Zinkernagel, A.S.; Mehra, M.R.; Schuepbach, R.A.; Ruschitzka, F.; Moch, H. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1417–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razdan, K.; Singh, K.; Singh, D. Vitamin D Levels and COVID-19 Susceptibility: Is there any Correlation? Med. Drug Discov. 2020, 7, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunville, C.F.; Mourani, P.M.; Ginde, A.A. The role of vitamin D in prevention and treatment of infection. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Targets 2013, 12, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranow, C. Vitamin D and the immune system. J. Investig. Med. 2011, 59, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miroliaee, A.E.; Salamzadeh, J.; Shokouhi, S.; Sahraei, Z. The study of vitamin D administration effect on CRP and Interleukin-6 as prognostic biomarkers of ventilator associated pneumonia. J. Crit. Care 2018, 44, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Leung, D.Y.M.; Richers, B.N.; Liu, Y.; Remigio, L.K.; Riches, D.W.; Goleva, E. Vitamin D Inhibits Monocyte/Macrophage Proinflammatory Cytokine Production by Targeting MAPK Phosphatase-1. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 2127–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.A.; Hunter, C.A. Is IL-6 a key cytokine target for therapy in COVID-19? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 337–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheller, J.; Chalaris, A.; Schmidt-Arras, D.; Rose-John, S. The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1813, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silberstein, M. COVID-19 and IL-6: Why vitamin D (probably) helps but tocilizumab might not. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 899, 174031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.M.; Ullah, A.; Randhawa, F.A.; Iqtadar, S.; Butt, N.F.; Waheed, K. Role of Vitamin D in reducing number of acute exacerbations in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) patients. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 33, 610–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, R.; Aleva, F.E.; Schrumpf, J.A.; Heijdra, Y.F.; Taube, C.; Daniels, J.M.; Lips, P.; Bet, P.M.; Hiemstra, P.S.; Van Der Ven, A.J.; et al. Prevention of exacerbations in patients with COPD and vitamin D deficiency through vitamin D supplementation (PRECOVID): A study protocol. BMC Pulm. Med. 2015, 15, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hughes, D.A.; Norton, R. Vitamin D and respiratory health. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2009, 158, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, E.K.; Thenappan, T.; Bhargava, M.; Chen, Y. Does Vitamin D deficiency increase the severity of COVID-19? Clin. Med. J. 2020, 20, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.L.; Nan, D.; Fernandez-Ayala, M.; García-Unzueta, M.; Hernández-Hernández, M.A.; López-Hoyos, M.; Muñoz-Cacho, P.; Olmos, J.M.; Gutiérrez-Cuadra, M.; Ruiz-Cubillán, J.J. Vitamin D Status in Hospitalized Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 106, e1343–e1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.; Memon, A.S.; Fatima, S.S. Increased Body Mass Index may lead to Hyperferritinemia Irrespective of Body Iron Stores. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 31, 1521–1526. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, T.N.; Eubanks, S.K.; Schaffer, K.J.; Zhou, C.Y.; Linder, M.C. Secretion of ferritin by rat hepatoma cells and its regulation by inflammatory cytokines and iron. Blood 1997, 90, 4979–4986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Ma, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, Z.; et al. The role of interleukin-6 in monitoring severe case of coronavirus disease 2019. EMBO Mol. Med. 2020, 12, e12421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amatore, D.; Sgarbanti, R.; Aquilano, K.; Baldelli, S.; Limongi, D.; Civitelli, L.; Nencioni, L.; Garaci, E.; Ciriolo, M.R.; Palamara, A.T. Influenza virus replication in lung epithelial cells depends on redox-sensitive pathways activated by NOX4 -derived ROS. Cell. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Minagawa, S.; Yoshida, M.; Araya, J.; Hara, H.; Imai, H.; Kuwano, K. Regulated Necrosis in Pulmonary Disease: A Focus on Necroptosis and Ferroptosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 62, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahotupa, M.; Asankari, T.J. Baseline diene conjugation in LDL lipids: An indicator of circulating oxidized LDL. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 27, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblat, M.; Volkova, N.; Coleman, R.; Aviram, M. Anti-oxidant and anti-atherogenic properties of liposomal glutathione: Studies in vitro, and in the atherosclerotic apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 2007, 195, e61–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdivia, A.O.; Ly, J.; Gonzalez, L.; Hussain, P.; Saing, T.; Islamoglu, H.; Pearce, D.; Ochoa, C.; Venketaraman, V. Restoring Cytokine Balance in HIV-Positive Individuals with Low CD4 T Cell Counts. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2017, 33, 905–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonikov, A. Endogenous Deficiency of Glutathione as the Most Likely Cause of Serious Manifestations and Death in COVID-19 Patients. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 1558–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavarría, A.P.; Vázquez, R.R.V.; Cherit, J.G.D.; Bello, H.H.; Suastegui, H.C.; Moreno-Castañeda, L.; Estrada, G.A.; Hernández, F.; González-Marcos, O.; Saucedo-Orozco, H.; et al. Antioxidants and pentoxifylline as coadjuvant measures to standard therapy to improve prognosis of patients with pneumonia by COVID-19. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1379–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, R.I.; Freeman, P.R.; Bruzzese, J. Efficacy of glutathione therapy in relieving dyspnea associated with COVID-19 pneumonia: A report of 2 cases. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2020, 30, 101063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khatchadourian, C.; Sisliyan, C.; Nguyen, K.; Poladian, N.; Tian, Q.; Tamjidi, F.; Luong, B.; Singh, M.; Robison, J.; Venketaraman, V. Hyperlipidemia and Obesity’s Role in Immune Dysregulation Underlying the Severity of COVID-19 Infection. Clin. Pract. 2021, 11, 694-707. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract11040085

Khatchadourian C, Sisliyan C, Nguyen K, Poladian N, Tian Q, Tamjidi F, Luong B, Singh M, Robison J, Venketaraman V. Hyperlipidemia and Obesity’s Role in Immune Dysregulation Underlying the Severity of COVID-19 Infection. Clinics and Practice. 2021; 11(4):694-707. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract11040085

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhatchadourian, Christopher, Christina Sisliyan, Kevin Nguyen, Nicole Poladian, Qi Tian, Faraaz Tamjidi, Bao Luong, Manpreet Singh, Jeremiah Robison, and Vishwanath Venketaraman. 2021. "Hyperlipidemia and Obesity’s Role in Immune Dysregulation Underlying the Severity of COVID-19 Infection" Clinics and Practice 11, no. 4: 694-707. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract11040085