Antiviral Activity of Ribosome-Inactivating Proteins

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Activity on Animal (Human) Viruses

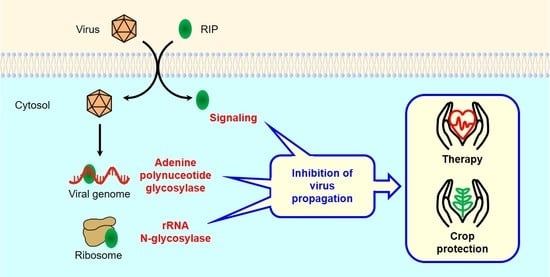

2.1. Activity on Human Immunodeficiency Virus

2.2. Activity on Herpes Simplex Virus

2.3. Activity on Other Animal Viruses

2.4. Citotoxicity of RIPs

3. Activity against Plant Viruses

4. Antiviral Mechanisms of RIPs

4.1. Antiviral Mechanisms of RIPs in Plants

4.1.1. Protein Synthesis Inhibition (rRNA N-glycosylase)

4.1.2. Adenine Polynucleotide Glycosylase Activity

4.1.3. Antiviral Protection through Signaling Pathways

4.2. Antiviral Mechanisms of RIPs in Animals

4.2.1. Protein Synthesis Inhibition (rRNA N-glycosylase)

4.2.2. Adenine Polynucleotide Glycosylase Activity

4.2.3. Antiviral Protection through Signaling Pathways

5. Experimental Therapy

5.1. RIPs and PEGylated RIPs

5.2. Immunotoxins and Other Conjugates

5.3. Designed Antiviral Proteins and Nanocapsules

5.4. Side Effects of RIP Therapy

6. Genetically Engineered Virus-Resistant Plants

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Clercq, E. Looking Back in 2009 at the Dawning of Antiviral Therapy Now 50 Years Ago: An Historical Perspective. In Advances in Virus Research; Maramorosch, K., Shatkin, A.J., Murphy, F.A., Eds.; Elsevier Academic Press Inc.: San Diego, CA, USA, 2009; Volume 73, pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, T.; Cheung, R.C.F.; Wong, J.H.; Chan, W.-Y. Proteins, peptides, polysaccharides, and nucleotides with inhibitory activity on human immunodeficiency virus and its enzymes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 10399–10414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musidlak, O.; Nawrot, R.; Goździcka-Józefiak, A. Which Plant Proteins Are Involved in Antiviral Defense? Review on In Vivo and In Vitro Activities of Selected Plant Proteins against Viruses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bolognesi, A.; Bortolotti, M.; Maiello, S.; Battelli, M.G.; Polito, L. Ribosome-Inactivating Proteins from Plants: A Historical Overview. Molecules 2016, 21, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreras, J.M.; Citores, L.; Iglesias, R.; Jiménez, P.; Girbés, T. Use of Ribosome-Inactivating Proteins from Sambucus for the Construction of Immunotoxins and Conjugates for Cancer Therapy. Toxins 2011, 3, 420–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stirpe, F. Ribosome-inactivating proteins: From toxins to useful proteins. Toxicon 2013, 67, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Maro, A.; Citores, L.; Russo, R.; Iglesias, R.; Ferreras, J.M. Sequence comparison and phylogenetic analysis by the Maximum Likelihood method of ribosome-inactivating proteins from angiosperms. Plant Mol. Biol. 2014, 85, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsnes, S. The history of ricin, abrin and related toxins. Toxicon 2004, 44, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polito, L.; Bortolotti, M.; Battelli, M.G.; Calafato, G.; Bolognesi, A. Ricin: An Ancient Story for a Timeless Plant Toxin. Toxins 2019, 11, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Domashevskiy, A.V.; Goss, D.J. Pokeweed Antiviral Protein, a Ribosome Inactivating Protein: Activity, Inhibition and Prospects. Toxins 2015, 7, 274–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Endo, Y.; Tsurugi, K. The RNA N-glycosidase activity of ricin A-chain. The characteristics of the enzymatic activity of ricin A-chain with ribosomes and with rRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 8735–8739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, R.; Citores, L.; Ferreras, J.M. Ribosomal RNA N-glycosylase Activity Assay of Ribosome-inactivating Proteins. Bio-Protocol 2017, 7, e2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citores, L.; Ragucci, S.; Ferreras, J.M.; Di Maro, A.; Iglesias, R. Ageritin, a Ribotoxin from Poplar Mushroom (Agrocybe aegerita) with Defensive and Antiproliferative Activities. ACS Chem. Biol. 2019, 14, 1319–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, L.; Ferreras, J.M.; Barraco, A.; Ricci, P.; Stirpe, F. Some ribosome-inactivating proteins depurinate ribosomal RNA at multiple sites. Biochem. J. 1992, 286, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barbieri, L.; Valbonesi, P.; Bonora, E.; Gorini, P.; Bolognesi, A.; Stirpe, F. Polynucleotide: Adenosine glycosidase activity of ribosome-inactivating proteins: Effect on DNA, RNA and poly(A). Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogasawara, T.; Sawasaki, T.; Morishita, R.; Ozawa, A.; Madin, K.; Endo, Y. A new class of enzyme acting on damaged ribosomes: Ribosomal RNA apurinic site specific lyase found in wheat germ. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 6522–6531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choudhary, N.L.; Yadav, O.P.; Lodha, M.L. Ribonuclease, deoxyribonuclease, and antiviral activity of Escherichia coli-expressed Bougainvillea xbuttiana antiviral protein-1. Biochemistry 2008, 73, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Yan, M.; Yu, M.; Yao, Q. 5’-AMP Phosphatase activity on trichosanthin and other single chain ribosome inactivating proteins. Chin. Biochem. J. 1996, 12, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Chen, W.-F.; Liu, W.-Y.; Wang, G.-H. Large-Scale Preparation of Two New Ribosome-Inactivating Proteins—Cinnamomin and Camphorin from the Seeds of Cinnamomum camphora. Protein Expr. Purif. 1997, 10, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmy, M.; Lombard, S.; Piéroni, G. Ricin RCA60: Evidence of Its Phospholipase Activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 258, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, N.; McDonald, K.A.; Jackman, A.P.; Girbés, T.; Iglesias, R. Bifunctional plant defence enzymes with chitinase and ribosome inactivating activities from Trichosanthes kirilowii cell cultures. Plant Sci. 1997, 130, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, R.; Citores, L.; Di Maro, A.; Ferreras, J.M. Biological activities of the antiviral protein BE27 from sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.). Planta 2014, 241, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polito, L.; Bortolotti, M.; Pedrazzi, M.; Mercatelli, D.; Battelli, M.G.; Bolognesi, A. Apoptosis and necroptosis induced by stenodactylin in neuroblastoma cells can be completely prevented through caspase inhibition plus catalase or necrostatin-1. Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Panda, P.K.; Behera, B.; Meher, B.R.; Das, D.N.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Sinha, N.; Naik, P.P.; Roy, B.; Das, J.; Paul, S.; et al. Abrus Agglutinin, a type II ribosome inactivating protein inhibits Akt/PH domain to induce endoplasmic reticulum stress mediated autophagy-dependent cell death. Mol. Carcinog. 2016, 56, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustgi, S.; Pollmann, S.; Buhr, F.; Springer, A.; Reinbothe, C.; Von Wettstein, D.; Reinbothe, S. JIP60-mediated, jasmonate- and senescence-induced molecular switch in translation toward stress and defense protein synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 14181–14186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Przydacz, M.; Jones, R.; Pennington, H.G.; Belmans, G.; Bruderer, M.; Greenhill, R.; Salter, T.; Wellham, P.A.; Cota, E.; Spanu, P.D. Mode of Action of the Catalytic Site in the N-Terminal Ribosome-Inactivating Domain of JIP60. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.-R.; Au, K.-Y.; Zheng, H.-Y.; Gao, L.-M.; Zhang, X.; Luo, R.-H.; Law, S.K.-Y.; Mak, A.N.-S.; Wong, K.-B.; Zhang, M.-X.; et al. The Recombinant Maize Ribosome-Inactivating Protein Transiently Reduces Viral Load in SHIV89.6 Infected Chinese Rhesus Macaques. Toxins 2015, 7, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Law, S.K.-Y.; Wang, R.-R.; Mak, A.N.-S.; Wong, K.-B.; Zheng, Y.-T.; Shaw, P.C. A switch-on mechanism to activate maize ribosome-inactivating protein for targeting HIV-infected cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 6803–6812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Au, K.-Y.; Wang, R.-R.; Wong, Y.-T.; Wong, K.-B.; Zheng, Y.-T.; Shaw, P.C. Engineering a switch-on peptide to ricin A chain for increasing its specificity towards HIV-infected cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2014, 1840, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foà-Tomasi, L.; Campadelli-Fiume, G.; Barbieri, L.; Stirpe, F. Effect of ribosome-inactivating proteins on virus-infected cells. Inhibition of virus multiplication and of protein synthesis. Arch. Virol. 1982, 71, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, B.B.; Burns, N.J.; Park, K.J.; Dawson, M.I.; Kende, M.; Sidwell, R.W. Antiviral immunotoxins: Antibody-mediated delivery of gelonin inhibits Pichinde virus replication in vitro. Antivir. Res. 1991, 15, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, T.K.; Collins, R.A.; Lam, T.L.; Ng, T.B.; Fong, W.P.; Wan, D. The plant ribosome inactivating proteins luffin and saporin are potent inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase. FEBS Lett. 2000, 471, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, H.-G.; Huang, P.L.; Zhang, D.; Sun, Y.; Chen, H.-C.; Zhang, J.; Huang, P.L.; Kong, X.-P.; Lee-Huang, S. A new activity of anti-HIV and anti-tumor protein GAP31: DNA adenosine glycosidase – Structural and modeling insight into its functions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 391, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee-Huang, S.; Kung, H.-F.; Huang, P.L.; Huang, P.L.; Li, B.-Q.; Huang, P.; Huang, H.I.; Chen, H.-C. A new class of anti-HIV agents: GAP31, DAPs 30 and 32. FEBS Lett. 1991, 291, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaur, I.; Gupta, R.C.; Puri, M. Ribosome inactivating proteins from plants inhibiting viruses. Virol. Sin. 2011, 26, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, E.F.; Ng, T.B.; Shaw, P.C.; Wong, R.N.S. Recent Progress in Medicinal Investigations on Trichosanthin and other Ribo-some Inactivating Proteins from the Plant Genus Trichosanthes. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 4410–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.-X.; Tam, S.-C. Trichosanthin affects HSV-1 replication in Hep-2 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 402, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.-W.; Wong, K.-B.; Shaw, P.C. Structural and Functional Investigation and Pharmacological Mechanism of Trichosanthin, a Type 1 Ribosome-Inactivating Protein. Toxins 2018, 10, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zheng, Y.T.; Ben, K.L.; Jin, S.W. Anti-HIV-1 activity of trichobitacin, a novel ribosome-inactivating protein. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2000, 21, 179–182. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, X. Preparation of an antitumor and antivirus agent: Chemical modification of α-MMC and MAP30 from Momordica Charantia L. with covalent conjugation of polyethyelene glycol. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 3133–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yao, X.; Li, J.; Deng, N.; Wang, S.; Meng, Y.; Shen, F. Immunoaffinity purification of α-momorcharin from bitter melon seeds (Momordica charantia). J. Sep. Sci. 2011, 34, 3092–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothan, H.A.; Bahrani, H.; Mohamed, Z.; Rahman, N.A.; Yusof, R. Fusion of Protegrin-1 and Plectasin to MAP30 Shows Significant Inhibition Activity against Dengue Virus Replication. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, P.L.; Li, J.J.; Huang, Y.Q.; Zhang, L.; Huang, P.L.; Lee-Huang, S. Anti-HIV Agent MAP30 Modulates the Expression Profile of Viral and Cellular Genes for Proliferation and Apoptosis in AIDS-Related Lymphoma Cells Infected with Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Virus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 287, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.M.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, J.; Zhu, S.; Ke, T.; Gao, D.F.; Xu, Y.B. Inhibition on Hepatitis B virus in vitro of recombinant MAP30 from bitter melon. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2007, 36, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Huang, S.; Huang, P.L.; Bourinbaiar, A.S.; Chen, H.C.; Kung, H.F. Inhibition of the integrase of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 by anti-HIV plant proteins MAP30 and GAP31. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 8818–8822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bourinbaiar, A.S.; Lee-Huang, S. The Activity of Plant-Derived Antiretroviral Proteins MAP30 and GAP31 against Herpes Simplex Virus Infectionin Vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996, 219, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, I.; Puri, M.; Ahmed, Z.; Blanchet, F.P.; Mangeat, B.; Piguet, V. Inhibition of HIV-1 Replication by Balsamin, a Ribosome Inactivating Protein of Momordica balsamina. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachinger, M.; Samtleben, R.; Gerhauser, C.; Wagner, H.; Erfle, V. Bryodin, a single-chain ribosome-inactivating protein, selectively inhibits the growth of HIV-1-infected cells and reduces HIV-1 production. Res. Exp. Med. 1993, 193, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitman, E.M.; Palmer, C.D.; Buus, S.; Chen, F.; Riddell, L.; Sims, S.; Klenerman, P.; Saez-Cirion, A.; Walker, B.D.; Hess, P.R.; et al. Saporin-conjugated tetramers identify efficacious anti-HIV CD8+ T-cell specificities. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yadav, S.K.; Batra, J.K. Mechanism of Anti-HIV Activity of Ribosome Inactivating Protein, Saporin. Protein Pept. Lett. 2015, 22, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivanco, J.M.; Tumer, N.E. Translation Inhibition of Capped and Uncapped Viral RNAs Mediated by Ribosome-Inactivating Proteins. Phytopathology 2003, 93, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mansouri, S.; Choudhary, G.; Sarzala, P.M.; Ratner, L.; Hudak, K.A. Suppression of Human T-cell Leukemia Virus I Gene Expression by Pokeweed Antiviral Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 31453–31462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rothan, H.A.; Bahrani, H.; Shankar, E.M.; Rahman, N.A.; Yusof, R. Inhibitory effects of a peptide-fusion protein (Latarcin–PAP1–Thanatin) against chikungunya virus. Antivir. Res. 2014, 108, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishag, H.Z.A.; Li, C.; Huang, L.; Sun, M.-X.; Ni, B.; Guo, C.-X.; Mao, X. Inhibition of Japanese encephalitis virus infection in vitro and in vivo by pokeweed antiviral protein. Virus Res. 2013, 171, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uckun, F.M.; Rustamova, L.; Vassilev, A.O.; Tibbles, H.E.; Petkevich, A.S. CNS activity of Pokeweed Anti-viral Protein (PAP) in mice infected with Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus (LCMV). BMC Infect. Dis. 2005, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, Y.-W.; Guo, C.-X.; Pan, Y.-F.; Peng, C.; Weng, Z.-H. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by pokeweed antiviral protein in vitro. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 1592–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamohan, F.; Venkatachalam, T.K.; Irvin, J.D.; Uckun, F.M. Pokeweed Antiviral Protein Isoforms PAP-I, PAP-II, and PAP-III Depurinate RNA of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 260, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, R.; Tumer, N.E. Pokeweed Antiviral Protein: Its Cytotoxicity Mechanism and Applications in Plant Disease Resistance. Toxins 2015, 7, 755–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ussery, M.A.; Irvin, J.D.; Hardesty, B. Inhibition of Poliovirus Replication by A Plant Antiviral Peptide. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1977, 284, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, M.S.; Hwang, K.M.; Caldwell, S.E.; Gaston, I.; Luk, K.C.; Wu, P.; Ng, V.L.; Crowe, S.; Daniels, J.; Marsh, J. GLQ223: An inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus replication in acutely and chronically infected cells of lymphocyte and mononuclear phagocyte lineage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 2844–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Byers, V.S.; Levin, A.S.; Waites, L.A.; Starrett, B.A.; Mayer, R.A.; Clegg, J.A.; Price, M.R.; Robins, R.A.; Delaney, M.; Baldwin, R.W. A phase I/II study of trichosanthin treatment of HIV disease. AIDS 1990, 4, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Wang, J.; Yan, H.; Chen, J.; Xia, K.; Liu, J.; Zhang, A. Effect of Radix Trichosanthis and Trichosanthin on Hepatitis B Virus in HepG2.2.15 Cells. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 15, 2094–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, L.; Battelli, M.G.; Stirpe, F. Ribosome-inactivating proteins from plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Biomembr. 1993, 1154, 237–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citores, L.; Iglesias, R.; Ferreras, J.M. Ribosome Inactivating Proteins from Plants: Biological Properties and their Use in Experimental Therapy. In Antitumor Potential and Other Emerging Medicinal Properties of Natural Compounds; Fang, E.F., Ng, T.B., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Q.; Yang, X.-Z.; Fu, L.-Y.; Lu, Y.-T.; Lu, Y.-H.; Zhao, J.; Wang, F.-J. Recombinant expression and purification of a MAP30-cell penetrating peptide fusion protein with higher anti-tumor bioactivity. Protein Expr. Purif. 2015, 111, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, B.; Yang, X.-Z.; Cao, X.-W.; Zhang, T.-Z.; Wang, F.-J.; Zhao, J. A novel trichosanthin fusion protein with increased cytotoxicity to tumor cells. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 39, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferens, W.A.; Hovde, C.J. Antiviral Activity of Shiga Toxin 1: Suppression of Bovine Leukemia Virus-Related Spontaneous Lymphocyte Proliferation. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 4462–4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shi, P.L.; Binnington, B.; Sakac, D.; Katsman, Y.; Ramkumar, S.; Gariépy, J.; Kim, M.; Branch, D.R.; Lingwood, C. Verotoxin A Subunit Protects Lymphocytes and T Cell Lines against X4 HIV Infection in Vitro. Toxins 2012, 4, 1517–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yadav, S.K.; Batra, J.K. Ribotoxin restrictocin manifests anti-HIV-1 activity through its specific ribonuclease activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 76, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.H.; Wang, H.X.; Ng, T.B. Marmorin, a new ribosome inactivating protein with antiproliferative and HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitory activities from the mushroom Hypsizigus marmoreus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 81, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ng, T.B. Isolation and characterization of velutin, a novel low-molecular-weight ribosome-inactivating protein from winter mushroom (Flammulina velutipes) fruiting bodies. Life Sci. 2001, 68, 2151–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.; Ng, T. First Simultaneous Isolation of a Ribosome Inactivating Protein and an Antifungal Protein from a Mushroom (Lyophyllum shimeji) Together with Evidence for Synergism of their Antifungal Effects. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001, 393, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.Z.; Yu, M.M.; Ooi, L.S.; Ng, T.B.; Chang, S.T.; Sun, S.S.; Ooi, V.E. Isolation and Characterization of a Type 1 Ribosome-Inactivating Protein from Fruiting Bodies of the Edible Mushroom (Volvariella volvacea). J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, I.; Akgul, H.; Kara, M. Saporin, a Polynucleotide–Adenosine Nucleosidase, May Be an Efficacious Therapeutic Agent for SARS-CoV-2 Infection. SLAS Discov. Adv. Life Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Y.; Ogg, S.; Ge, H. Novel Binding Mechanisms of Fusion Broad Range Anti-Infective Protein Ricin A Chain Mutant-Pokeweed Antiviral Protein 1 (RTAM-PAP1) against SARS-CoV-2 Key Proteins in Silico. Toxins 2020, 12, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbussche, F.; Desmyter, S.; Ciani, M.; Proost, P.; Peumans, W.J.; Van Damme, E.J.M. Analysis of the in planta antiviral activity of elderberry ribosome-inactivating proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004, 271, 1508–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbussche, F.; Peumans, W.J.; Desmyter, S.; Proost, P.; Ciani, M.; Van Damme, E.J.M. The type-1 and type-2 ribosome-inactivating proteins from Iris confer transgenic tobacco plants local but not systemic protection against viruses. Planta 2004, 220, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.-X.; Hou, P.; Wei, Q.; Xu, Y.; Chen, F. A ribosome-inactivating protein (curcin 2) induced from Jatropha curcas can reduce viral and fungal infection in transgenic tobacco. Plant Growth Regul. 2007, 54, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Y.-H.; Wong, Y.-S.; Wang, B.; Wong, R.N.-S.; Yeung, H.-W.; Shaw, P.-C. Use of trichosanthin to reduce infection by turnip mosaic virus. Plant Sci. 1996, 114, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R.; McDonald, K.A.; Dandekar, A.M.; Jackman, A.P.; Falk, B. Expression of recombinant trichosanthin, a ribosome-inactivating protein, in transgenic tobacco. J. Biotechnol. 2002, 97, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhang, P.; Meng, Y.-F.; Xu, F.; Zhang, D.-W.; Cheng, J.; Lin, H.-H.; Xi, D. Alpha-momorcharin, a RIP produced by bitter melon, enhances defense response in tobacco plants against diverse plant viruses and shows antifungal activity in vitro. Planta 2012, 237, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Meng, Y.; Chen, L.-J.; Lin, H.; Xi, D.-H. The Roles of Alpha-Momorcharin and Jasmonic Acid in Modulating the Response of Momordica charantia to Cucumber Mosaic Virus. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruan, X.-L.; Liu, L.-F.; Li, H. Transgenic tobacco plants with ribosome inactivating protein gene cassin from Cassia occidentalis and their resistance to tobacco mosaic virus. J. Plant Physiol. Mol. Biol. 2007, 33, 517–523. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y.; Saunders, K.; Hartley, M.R.; Stanley, J. Resistance to Geminivirus Infection by Virus-Induced Expression of Dianthin in Transgenic Plants. Virology 1996, 220, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stirpe, F.; Williams, D.G.; Onyon, L.J.; Legg, R.F.; Stevens, W.A. Dianthins, ribosome-damaging proteins with anti-viral properties from Dianthus caryophyllus L. (carnation). Biochem. J. 1981, 195, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iglesias, R.; Pérez, Y.; de Torre, C.; Ferreras, J.M.; Antolín, P.; Jiménez, P.; Ángeles Rojo, M.; Méndez, E.; Girbés, T. Molecular characterization and systemic induction of single-chain ribosome-inactivating proteins (RIPs) in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris) leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iglesias, R.; Citores, L.; Ragucci, S.; Russo, R.; Di Maro, A.; Ferreras, J.M. Biological and antipathogenic activities of ribosome-inactivating proteins from Phytolacca dioica L. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2016, 1860, 1256–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Sadhana, P.; Begum, M.; Kumar, S.; Lodha, M.; Kapoor, H. Purification, characterization and cloning of antiviral/ribosome inactivating protein from Amaranthus tricolor leaves. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 1865–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.-Y.; An, C.S.; Liu, J.R.; Paek, K.-H. A Ribosome–Inactivating Protein fromAmaranthus viridis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1997, 61, 1613–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, A. Purification of a ribosome-inactivating protein with antioxidation and root developer potencies from Celosia plumosa. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2018, 25, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranwal, V.K.; Tumer, N.E.; Kapoor, H.C. Depurination of ribosomal RNA and inhibition of viral RNA translation by an antiviral protein of Celosia cristata. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2002, 40, 1195–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubrahmanyam, A.; Baranwal, V.K.; Lodha, M.; Varma, A.; Kapoor, H. Purification and properties of growth stage-dependent antiviral proteins from the leaves of Celosia cristata. Plant Sci. 2000, 154, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begam, M.; Kumar, S.; Roy, S.; Campanella, J.J.; Kapoor, H. Molecular cloning and functional identification of a ribosome inactivating/antiviral protein from leaves of post-flowering stage of Celosia cristata and its expression in E. coli. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 2441–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutt, S.; Narwal, S.; Kapoor, H.C.; Lodha, M.L. Isolation and Characterization of Two Protein Isoforms with Antiviral Activity from Chenopodium album L Leaves. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2003, 12, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-S.; Hwang, D.-J.; Lee, S.-M.; Kim, Y.-T.; Choi, S.-B.; Cho, K.-J. Ribosome-inactivating activity and cDNA cloning of antiviral protein isoforms of Chenopodium album. Mol. Cells 2004, 17, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Torky, Z.A. Isolation and characterization of antiviral protein from Salsola longifolia leaves expressing polynucleotide adenosine glycoside activity. TOJSAT 2012, 2, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Straub, P.; Adam, G.; Mundry, K.-W. Isolation and Characterization of a Virus Inhibitor from Spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.). J. Phytopathol. 1986, 115, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawade, K.; Ishizaki, T.; Masuda, K. Differential expression of ribosome-inactivating protein genes during somatic embryogenesis in spinach (Spinacia oleracea). Physiol. Plant. 2008, 134, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.H.; Song, S.K.; Choi, K.W.; Lee, J.S. Expression of a cDNA encoding Phytolacca insularis antiviral protein confers virus resistance on transgenic potato plants. Mol. Cells 1997, 7, 807–815. [Google Scholar]

- Bulgari, D.; Landi, N.; Ragucci, S.; Faoro, F.; Di Maro, A. Antiviral Activity of PD-L1 and PD-L4, Type 1 Ribosome Inactivating Proteins from Leaves of Phytolacca dioica L. in the Pathosystem Phaseolus vulgaris–Tobacco Necrosis Virus (TNV). Toxins 2020, 12, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipahioglu, H.M.; Kaya, I.; Usta, M.; Ünal, M.; Ozcan, D.; Özer, M.; Güller, A.; Pallás, V. Pokeweed (Phytolacca americana L.) antiviral protein inhibits Zucchini yellow mosaic virus infection in a dose-dependent manner in squash plants. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2017, 41, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodge, J.K.; Kaniewski, W.K.; Tumer, N.E. Broad-spectrum virus resistance in transgenic plants expressing pokeweed antiviral protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 7089–7093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Domashevskiy, A.V.; Williams, S.; Kluge, C.; Cheng, S.-Y. Plant Translation Initiation Complex eIFiso4F Directs Pokeweed Antiviral Protein to Selectively Depurinate Uncapped Tobacco Etch Virus RNA. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 5980–5990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Zoubenko, O.; Tumer, N.E. Reduced toxicity and broad spectrum resistance to viral and fungal infection in transgenic plants expressing pokeweed antiviral protein II. Plant Mol. Biol. 1998, 38, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolognesi, A.; Polito, L.; Olivieri, F.; Valbonesi, P.; Barbieri, L.; Battelli, M.G.; Carusi, M.V.; Benvenuto, E.; Blanco, F.D.V.; Di Maro, A.; et al. New ribosome-inactivating proteins with polynucleotide:adenosine glycosidase and antiviral activities from Basella rubra L. and Bougainvillea spectabilis Willd. Planta 1997, 203, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S.; Verma, H.N.; Srivastava, A.; Prasad, V. BDP-30, a systemic resistance inducer from Boerhaavia diffusa L., suppresses TMV infection, and displays homology with ribosome-inactivating proteins. J. Biosci. 2015, 40, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolognesi, A.; Polito, L.; Lubelli, C.; Barbieri, L.; Parente, A.; Stirpe, F. Ribosome-inactivating and Adenine Polynucleotide Glycosylase Activities in Mirabilis jalapa L. Tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 13709–13716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Güller, A.; Sipahioğlu, H.M.; Usta, M.; Durak, E.D. Antiviral and Antifungal Activity of Biologically Active Recombinant Bouganin Protein from Bougainvillea spectabilis Willd. J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 24, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Narwal, S.; Balasubrahmanyam, A.; Lodha, M.L.; Kapoor, H.C. Purification and properties of antiviral proteins from the leaves of Bougainvillea xbuttiana. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 2001, 38, 342–347. [Google Scholar]

- Narwal, S.; Balasubrahmanyam, A.; Sadhna, P.; Kapoor, H.; Lodha, M.L. A systemic resistance inducing antiviral protein with N-glycosidase activity from Bougainvillea xbuttiana leaves. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2001, 39, 600–603. [Google Scholar]

- Olivieri, F.; Prasad, V.; Valbonesi, P.; Srivastava, S.; Ghosal-Chowdhury, P.; Barbieri, L.; Bolognesi, A.; Stirpe, F. A systemic antiviral resistance-inducing protein isolated from Clerodendrum inerme Gaertn. is a polynucleotide:adenosine glycosidase (ribosome-inactivating protein). FEBS Lett. 1996, 396, 132–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prasad, V.; Mishra, S.K.; Srivastava, S.; Srivastava, A. A virus inhibitory protein isolated from Cyamopsis tetragonoloba (L.) Taub. upon induction of systemic antiviral resistance shares partial amino acid sequence homology with a lectin. Plant Cell Rep. 2014, 33, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, H.; Srivastava, S.; Kumar, D. Induction of Systemic Resistance in Plants Against Viruses by a Basic Protein from Clerodendrum aculeatum Leaves. Phytopathology 1996, 86, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, H.N.; Tewari, K.K.; Kumar, D.; Tuteja, N. Cloning and characterisation of a gene encoding an antiviral protein from Clerodendrum aculeatum L. Plant Mol. Biol. 1997, 33, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Trivedi, S.; Krishna, S.K.; Verma, H.N.; Prasad, V. Suppression of Papaya ringspot virus infection in Carica papaya with CAP-34, a systemic antiviral resistance inducing protein from Clerodendrum aculeatum. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2008, 123, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Peumans, W.J.; Van Damme, E.J.M. The Sambucus nigratype-2 ribosome-inactivating protein SNA-I’ exhibits in planta antiviral activity in transgenic tobacco. FEBS Lett. 2002, 516, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iglesias, R.; Pérez, Y.; Citores, L.; Ferreras, J.M.; Méndez, E.; Girbés, T. Elicitor-dependent expression of the ribosome-inactivating protein beetin is developmentally regulated. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, T.; Zhu, L.-S.; Meng, Y.; Lv, R.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, L.; Lin, H.-H.; Xi, D. Alpha-momorcharin enhances Tobacco mosaic virus resistance in tobacco NN by manipulating jasmonic acid-salicylic acid crosstalk. J. Plant Physiol. 2018, 223, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, S.M.; Beevers, H. Ricin inhibition of in vitro protein synthesis by plant ribosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79, 5935–5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iglesias, R.; Arias, F.; Ángeles Rojo, M.; Escarmis, C.; Ferreras, J.M.; Girbés, T. Molecular action of the type 1 ribosome-inactivating protein saporin 5 on Vicia sativa ribosomes. FEBS Lett. 1993, 325, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ángeles Rojo, M.; Arias, F.; Ferreras, J.M.; Iglesias, R.; Muñoz, R.; Girbés, T. Development of a cell-free translation system from Cucumis melo: Preparation, optimization and evaluation of sensitivity to some translational inhibitors. Plant Sci. 1993, 90, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ángeles Rojo, M.; Arias, F.; Iglesias, R.; Ferreras, J.M.; Munoz, R.; Girbés, T. A Cucumis sativus cell-free translation system: Preparation, optimization and sensitivity to some antibiotics and ribosome-inactivating proteins. Physiol. Plant. 1993, 88, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonness, M.S.; Ready, M.P.; Irvin, J.D.; Mabry, T.J. Pokeweed antiviral protein inactivates pokeweed ribosomes; implications for the antiviral mechanism. Plant J. 1994, 5, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.; Massiah, A.; Lomonossoff, G.; Roberts, L.M.; Lord, J.M.; Hartley, M. Correlation between the activities of five ribosome-inactivating proteins in depurination of tobacco ribosomes and inhibition of tobacco mosaic virus infection. Plant J. 1994, 5, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-W.; Vepachedu, R.; Sharma, N.; Vivanco, J.M. Ribosome-inactivating proteins in plant biology. Planta 2004, 219, 1093–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luvisi, A.; Panattoni, A.; Materazzi, A.; Rizzo, D.; De Bellis, L.; Aprile, A.; Sabella, E.; Rinaldelli, E. Early trans-plasma membrane responses to Tobacco mosaic virus infection. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2017, 39, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girbés, T.; Ferreras, J.M. Ribosome-inactivating proteins from plants. Recent Res. Dev. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1998, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hudak, K.A.; Wang, P.; Tumer, N.E. A novel mechanism for inhibition of translation by pokeweed antiviral protein: Depurination of the capped RNA template. RNA 2000, 6, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zoubenko, O.; Hudak, K.; Tumer, N.E. A non-toxic pokeweed antiviral protein mutant inhibits pathogen infection via a novel salicylic acid-independent pathway. Plant Mol. Biol. 2000, 44, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, D.; Kao, C.C.; Hudak, K.A. Pokeweed Antiviral Protein Inhibits Brome Mosaic Virus Replication in Plant Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 20069–20075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karran, R.A.; Hudak, K.A. Depurination of Brome mosaic virus RNA3 inhibits its packaging into virus particles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 7209–7222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, G.S.; Yamini, S.; Kumar, M.; Sinha, M.; Kaur, P.; Sharma, S.; Singh, T.P. First structural evidence of sequestration of mRNA cap structures by type 1 ribosome inactivating protein from Momordica balsamina. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2013, 81, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhu, P.; Xu, F.; Che, Y.; Ma, Y.; Ji, Z.-L. Alpha-momorcharin enhances Nicotiana benthamiana resistance to tobacco mosaic virus infection through modulation of reactive oxygen species. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2020, 21, 1212–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smirnov, S.; Shulaev, V.; Tumer, N.E. Expression of Pokeweed Antiviral Protein in Transgenic Plants Induces Virus Resistance in Grafted Wild-Type Plants Independently of Salicylic Acid Accumulation and Pathogenesis-Related Protein Synthesis. Plant Physiol. 1997, 114, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zoubenko, O.; Uckun, F.; Hur, Y.; Chet, I.; Tumer, N. Plant resistance to fungal infection induced by nontoxic pokeweed antiviral protein mutants. Nat. Biotechnol. 1997, 15, 992–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vind, A.C.; Genzor, A.V.; Bekker-Jensen, S. Ribosomal stress-surveillance:Three pathways is a magic number. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 10648–10661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arunachalam, C.; Doohan, F.M. Trichothecene toxicity in eukaryotes: Cellular and molecular mechanisms in plants and animals. Toxicol. Lett. 2013, 217, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madan, S.; Ghosh, P.C. Interaction of gelonin with macrophages: Effect of lysosomotropic amines. Exp. Cell Res. 1992, 198, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.Y.; Huang, H.; Tam, S.C. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of trichosanthin in choriocarcinoma cells. Toxicology 2003, 186, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, M.C.; Peek, C.T.; Becker, M.M.; Smith, E.C.; Denison, M.R. Coronaviruses Induce Entry-Independent, Continuous Macropinocytosis. MBio 2014, 5, e01340-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schelhaas, M. Come in and take your coat off—How host cells provide endocytosis for virus entry. Cell. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 1378–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teltow, G.J.; Irvin, J.D.; Aron, G.M. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus DNA synthesis by pokeweed antiviral protein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1983, 23, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zarling, J.M.; Moran, P.A.; Haffar, O.; Sias, J.; Richman, D.D.; Spina, C.A.; Myers, D.E.; Kuebelbeck, V.; Ledbetter, J.A.; Uckun, F.M. Inhibition of HIV replication by pokeweed antiviral protein targeted to CD4+ cells by monoclonal antibodies. Nature 1990, 347, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krivdova, G.; Hudak, K.A. Pokeweed antiviral protein restores levels of cellular APOBEC3G during HIV-1 infection by depurinating Vif mRNA. Antivir. Res. 2015, 122, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhabokritsky, A.; Mansouri, S.; Hudak, K.A. Pokeweed antiviral protein alters splicing of HIV-1 RNAs, resulting in reduced virus production. RNA 2014, 20, 1238–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.-X.; Neamati, N.; Jacob, J.; Palmer, I.; Stahl, S.J.; Kaufman, J.D.; Huang, P.L.; Huang, P.L.; Winslow, H.E.; Pommier, Y.; et al. Solution Structure of Anti-HIV-1 and Anti-Tumor Protein MAP30: Structural insights into its multiple functions. Cell 1999, 99, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, W.-L.; Feng, D.; Wu, J.; Sui, S.-F. Trichosanthin inhibits integration of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 through depurinating the long-terminal repeats. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2009, 37, 2093–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-X.; Yeung, H.-W.; Pan, L.-P.; Chan, S.I. Trichosanthin, a potent HIV-1 inhibitor, can cleave supercoiled DNA in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991, 19, 6309–6312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, P.L.; Chen, H.C.; Kung, H.F.; Huang, P.; Huang, H.I.; Lee-Huang, S. Anti-HIV plant proteins catalyze topological changes of DNA into inactive forms. BioFactors 1992, 4, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.-L.; Zhang, F.; Feng, D.; Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Sui, S.-F. A novel sorting strategy of trichosanthin for hijacking human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 384, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Feng, D.; Sun, S.; Han, T.; Sui, S. The anti-viral protein of trichosanthin penetrates into human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2009, 42, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, N.; Zheng, Y.; Tam, S.-C. The anti-herpetic activity of trichosanthin via the nuclear factor-κB and p53 pathways. Life Sci. 2012, 90, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, D.-Y.; Chan, H.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Huang, H.; Tam, S.-C.; Zheng, Y.-T. An inhibitor of c-Jun N-terminal kinases (CEP-11004) counteracts the anti-HIV-1 action of trichosanthin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 339, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, D.; Yau, K.; He, X.-H.; Shi, H.; Zheng, Y.; Tam, S.-C. Conversion of trichosanthin-induced CD95 (Fas) type I into type II apoptotic signaling during Herpes simplex virus infection. Mol. Immunol. 2011, 48, 2000–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Chan, H.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Ouyang, D.-Y.; Zheng, Y.-T.; Tam, S.-C. Trichosanthin suppresses the elevation of p38 MAPK, and Bcl-2 induced by HSV-1 infection in Vero cells. Life Sci. 2006, 79, 1287–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.C.-C.; Peterson, A.; Zinshteyn, B.; Regot, S.; Green, R. Ribosome Collisions Trigger General Stress Responses to Regulate Cell Fate. Cell 2020, 182, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, J.O.; Gorelick, K.J.; Gatti, G.; Arri, C.J.; Lifson, J.D.; Gambertoglio, J.G.; Boström, A.; Williams, R. Safety, activity, and pharmacokinetics of GLQ223 in patients with AIDS and AIDS-related complex. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1994, 38, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Byers, V.; Levin, A.; Malvino, A.; Waites, L.; Robins, R.; Baldwin, R. A Phase II Study of Effect of Addition of Trichosanthin to Zidovudine in Patients with HIV Disease and Failing Antiretroviral Agents. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 1994, 10, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-S.; Jun, S.-Y.; Shin, T.-H. Critical Issues in the Development of Immunotoxins for Anticancer Therapy. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 109, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rust, A.; Partridge, L.J.; Davletov, B.; Hautbergue, G.M. The Use of Plant-Derived Ribosome Inactivating Proteins in Immunotoxin Development: Past, Present and Future Generations. Toxins 2017, 9, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spiess, K.; Jakobsen, M.H.; Kledal, T.N.; Rosenkilde, M.M. The future of antiviral immunotoxins. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2016, 99, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berger, E.A.; Pastan, I. Immunotoxin Complementation of HAART to Deplete Persisting HIV-Infected Cell Reservoirs. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tazzari, P.L.; De Totero, D.; Bolognesi, A.; Testoni, N.; Pileri, S.; Roncella, S.; Reato, G.; Stein, H.; Gobbi, M.; Stirpe, F. An Epstein-Barr virus-infected lymphoblastoid cell line (D430B) that grows in SCID-mice with the morphologic features of a CD30+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma, and is sensitive to anti-CD30 immunotoxins. Haematology 1999, 84, 988–995. [Google Scholar]

- Tedder, T.F.; Goldmacher, V.S.; Lambert, J.M.; Schlossman, S.F. Epstein Barr virus binding induces internalization of the C3d receptor: A novel immunotoxin delivery system. J. Immunol. 1986, 137, 1387–1391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smee, D.F.; Sidwell, R.W.; Barnett, B.B. Combination of antiviral immunotoxin and ganciclovir or cidofovir for the treatment of murine cytomegalovirus infections. Antivir. Res. 1996, 32, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Till, M.A.; Ghetie, V.; Gregory, T.; Patzer, E.J.; Porter, J.P.; Uhr, J.W.; Capon, D.J.; Vitetta, E.S. HIV-infected cells are killed by rCD4-ricin A chain. Science 1988, 242, 1166–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, Y.; Ogg, S.; Ge, H. Expression of novel fusion antiviral proteins ricin a chain-pokeweed antiviral proteins (RTA-PAPs) in Escherichia coli and their inhibition of protein synthesis and of hepatitis B virus in vitro. BMC Biotechnol. 2018, 18, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Matsushita, S.; Koito, A.; Maeda, Y.; Hattori, T.; Takatsuki, K. Selective Killing of HIV-Infected Cells by Anti-gp120 Immunotoxins. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 1990, 6, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.W.; Fung, M.S.; Sun, N.C.; Sun, C.R.; Chang, N.T.; Chang, T.W. Immunoconjugates that neutralize HIV virions kill T cells infected with diverse strains of HIV-1. J. Immunol. 1990, 144, 1257–1262. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus, S.H.; McClure, J. Soluble CD4 enhances the efficacy of immunotoxins directed against gp41 of the human immunodeficiency virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sadraeian, M.; Guimarães, F.E.G.; Araujo, A.P.U.; Worthylake, D.K.; Lecour, L.J.; Pincus, S.H. Selective cytotoxicity of a novel immunotoxin based on pulchellin A chain for cells expressing HIV envelope. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pincus, S.H.; Song, K.; Maresh, G.A.; Hamer, D.H.; Dimitrov, D.S.; Chen, W.; Zhang, M.-Y.; Ghetie, V.F.; Chan-Hui, P.-Y.; Robinson, J.E.; et al. Identification of Human Anti-HIV gp160 Monoclonal Antibodies That Make Effective Immunotoxins. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e01955-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pincus, S.H.; Cole, R.L.; Hersh, E.M.; Lake, D.; Masuho, Y.; Durda, P.J.; McClure, J. In vitro efficacy of anti-HIV immunotoxins targeted by various antibodies to the envelope protein. J. Immunol. 1991, 146, 4315–4324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Till, M.A.; Zolla-Pazner, S.; Gorny, M.K.; Patton, J.S.; Uhr, J.W.; Vitetta, E.S. Human immunodeficiency virus-infected T cells and monocytes are killed by monoclonal human anti-gp41 antibodies coupled to ricin A chain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 1987–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pincus, S.H.; Song, K.; Maresh, G.A.; Frank, A.; Worthylake, D.; Chung, H.-K.; Polacino, P.; Hamer, D.H.; Coyne, C.P.; Rosenblum, M.G.; et al. Design and In Vivo Characterization of Immunoconjugates Targeting HIV gp160. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e01360-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McCoig, C.; Van Dyke, G.; Chou, C.-S.; Picker, L.J.; Ramilo, O.; Vitetta, E.S. An anti-CD45RO immunotoxin eliminates T cells latently infected with HIV-1 in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 11482–11485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erice, A.; Balfour, H.H.; Myers, D.E.; Leske, V.L.; Sannerud, K.J.; Kuebelbeck, V.; Irvin, J.D.; Uckun, F.M. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity of an anti-CD4 immunoconjugate containing pokeweed antiviral protein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1993, 37, 835–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bell, K.D.; Ramilo, O.; Vitetta, E.S. Combined use of an immunotoxin and cyclosporine to prevent both activated and quiescent peripheral blood T cells from producing type 1 human immunodeficiency virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 1411–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barnett, B.B.; Smee, D.F.; Malek, S.M.; Sidwell, R.W. Selective cytotoxicity of ricin A chain immunotoxins towards murine cytomegalovirus-infected cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996, 40, 470–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caizhen, G.; Yan, G.; Ronron, C.; Lirong, Y.; Panpan, C.; Xuemei, H.; Yuanbiao, Q.; Li, Q.S. Zirconium phosphatidylcholine-based nanocapsules as an in vivo degradable drug delivery system of MAP30, a momordica anti-HIV protein. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 483, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Yan, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Xie, Y.; Lu, Y.; Kamata, M.; Chen, I.S.Y. Specific Elimination of Latently HIV-1 Infected Cells Using HIV-1 Protease-Sensitive Toxin Nanocapsules. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szafraniec-Szczęsny, J.; Janik-Hazuka, M.; Odrobińska, J.; Zapotoczny, S. Polymer Capsules with Hydrophobic Liquid Cores as Functional Nanocarriers. Polymers 2020, 12, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzo, E.; Di Maro, A. A new age for biomedical applications of Ribosome Inactivating Proteins (RIPs): From bioconjugate to nanoconstructs. J. Biomed. Sci. 2016, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Giansanti, F.; Flavell, D.J.; Angelucci, F.; Fabbrini, M.S.; Ippoliti, R. Strategies to Improve the Clinical Utility of Saporin-Based Targeted Toxins. Toxins 2018, 10, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nicaise, V. Crop immunity against viruses: Outcomes and future challenges. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, D.; Sudarshana, M.; Fuchs, M.; Rao, N.; Thottappilly, G. Genetically Engineered Virus-Resistant Plants in Developing Countries: Current Status and Future Prospects. Adv. Virus Res. 2009, 75, 185–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, G.Y.; Jin, D.M.; Weng, M.L.; Guo, B.T.; Wang, B. Transformation and expression of trichosanthin gene in tomato. Acta Bot. Sin. 1999, 41, 334–336. [Google Scholar]

- Tumer, N.E.; Hwang, D.-J.; Bonness, M. C-terminal deletion mutant of pokeweed antiviral protein inhibits viral infection but does not depurinate host ribosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 3866–3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pauli, S.; Rothnie, H.M.; Chen, G.; He, X.; Hohn, T. The Cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S Promoter Extends into the Transcribed Region. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 12120–12128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Activity | Example of RIP | References |

|---|---|---|

| Agglutinin | Ricin | [8] |

| Antiviral | PAP | [10] |

| rRNA N-glycosylase | Ricin | [11] |

| Adenine polynucleotide glycosylase | Saporin-L1 | [15] |

| rRNA N-glycosylase/lyase | Gypsophilin/RALyase | [16] |

| RNase | BBAP1 | [17] |

| DNase | BBAP1 | [17] |

| Phosphatase | Trichosanthin | [18] |

| Superoxide dismutase | Camphorin | [19] |

| Phospholipase | Ricin | [20] |

| Chitinase | TKC 28-I | [21] |

| DNA nicking | BE27 | [22] |

| Apoptosis induction | Stenodactylin | [4,23] |

| Necroptosis induction | Stenodactylin | [4,23] |

| Autophagia induction | Abrus Agglutinin | [24] |

| Senescence induction | JIP60 | [25] |

| Plant tissue necrosis | JIP60 | [26] |

| Species and RIP | Virus | References |

|---|---|---|

| POACEAE | ||

| Zea mays L. | ||

| Maize RIP | HIV, SHIV | [27,28] |

| EUPHORBIACEAE | ||

| Ricinus communis L. | ||

| Ricin A chain | HIV | [29] |

| Suregada multiflora (A.Juss.) Baill. (=Gelonium multiflorum A.Juss.) | ||

| Gelonin | HIV, HPV, HSV, PICV, | [2,30,31,32] |

| GAP31 | HIV | [33,34] |

| CUCURBITACEAE | ||

| Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim | ||

| Trichosanthin (TCS) | HBV, HIV, HSV | [32,35,36,37,38] |

| TAP29 | HIV | [36] |

| Trichobitacin | HIV | [36,39] |

| Momordica charantia L. | ||

| Momordin (M. charantia inhibitor) | HPV, HSV | [30] |

| Alpha-momorcharin (α-MMC) | HBV, HIV, HSV | [2,32,40,41] |

| Beta-momorcharin | HIV | [2,32] |

| Momordica antiviral protein (MAP30) | DENV-2, HHV8, HBV, HIV, HSV | [35,42,43,44,45,46] |

| Momordica balsamina L. | ||

| Balsamin | HIV | [47] |

| Luffa cylindrica (L.) M.Roem. | ||

| Luffin | HIV | [32] |

| Bryonia cretica subsp. dioica (Jacq.) Tutin (=Bryonia dioica Jacq.) | ||

| Bryodin | HIV | [48] |

| CARYOPHYLLACEAE | ||

| Saponaria officinalis L. | ||

| Saporin | HIV | [32,49,50] |

| Dianthus caryophyllus L. | ||

| Dianthin 32 (DAP32) | HIV, HPV, HSV | [30,34] |

| Dianthin 30 (DAP30) | HIV | [34] |

| Agrostemma githago L. | ||

| Agrostin | HIV | [2,32] |

| PHYTOLACCACEAE | ||

| Phytolacca americana L. | ||

| PAP (PAPI) | CHIKV, FLUV, HBV, HIV, HPV, | [10,35,51,52,53,54,55,56,57] |

| HSV, HTLV, JEV, LCMV | ||

| PAPII | HIV | [57] |

| PAPIII | HIV | [57] |

| PAP-S | HSV, HPV, HBV | [30,56] |

| Species and RIP | Virus | References |

|---|---|---|

| IRIDACEAE | ||

| Iris x hollandica Tub. | ||

| IRIP | TMV, TEV | [77] |

| IRAb | TMV, TEV | [77] |

| EUPHORBIACEAE | ||

| Jatropha curcas L. | ||

| Curcin 2 | TMV | [78] |

| CUCURBITACEAE | ||

| Trichosanthes kirilowii Maxim | ||

| Trichosanthin | TuMV, CMV, TMV | [79,80] |

| Momordica charantia L. | ||

| α-Momorcharin | CMV, ChiVMV, TMV, TuMV | [81,82] |

| LEGUMINOSAE | ||

| Senna occidentalis (L.) Link (=Cassia occidentalis L.) | ||

| Cassin | TMV | [83] |

| CARYOPHYLLACEAE | ||

| Saponaria officinalis L. | ||

| Saporin | BMV, TMV, AMV | [51] |

| Dianthus caryophyllus L. | ||

| Dianthin 30 | ACMV, TMV | [84,85] |

| Dianthin 32 | TMV | [85] |

| AMARANTHACEAE | ||

| Beta vulgaris L. | ||

| BE27 | TMV, AMCV | [86,87] |

| Amaranthus tricolor L. | ||

| AAP-27 | SHMV | [88] |

| Amaranthus viridis L. | ||

| Amaranthin | TMV | [89] |

| Celosia argentea L. (=Celosia cristata L., = Celosia plumosa (Voss) Burv.) | ||

| CCP 25 | BMV, PMV, TMV, SHMV, ICRSV | [90,91,92] |

| CCP 27 | TMV, SHMV, ICRSV | [92,93] |

| Chenopodium album L. | ||

| CAP-I | TMV, SHMV | [94] |

| CAP-II | TMV, SHMV | [94] |

| CAP30 | TMV | [95] |

| Salsola longifolia Forssk. | ||

| SLP-32 | BYMV, TNV | [96] |

| Spinacia oleracea L. | ||

| VI (SoRIP2) | TMV | [97,98] |

| PHYTOLACCACEAE | ||

| Phytolacca insularis Nakai | ||

| PIP | TMV, CMV, PVY, PVX, PLRV | [99] |

| Phytolacca dioica L. | ||

| Dioicin 2 | TMV | [87] |

| PD-S2 | TMV | [87] |

| PD-L1 | TNV | [100] |

| PD-L4 | TMV, TNV | [87,100] |

| Phytolacca americana L. | ||

| PAP (PAPI) | BMV, TMV, AMV, TBSV, SPMV, ZYMV | [51,58,101,102,103,104,105] |

| CMV, PVY, PVX, TEV, SBMV | ||

| PAPII | TMV, PVX | [104] |

| PAP-S | AMCV | [105] |

| NYCTAGINACEAE | ||

| Boerhaavia diffusa L. | ||

| BDP-30 | TMV | [106] |

| Mirabilis expansa (Ruiz & Pav.) Standl. | ||

| ME1 | TMV, BMV | [51] |

| Mirabilis jalapa L. | ||

| MAP | TMV | [107] |

| Bougainvillea spectabilis Willd. | ||

| Bouganin | ZYMV, AMCV | [105,108] |

| Bougainvillea buttiana Holttum & Standl. | ||

| BBAP1 | SHMV | [17] |

| BBP-24 | TMV, SHMV | [109,110] |

| BBP-28 | TMV, SHMV | [109,110] |

| BASELLACEAE | ||

| Basella alba L. (=Basella rubra L.) | ||

| RIP2 | AMCV | [105] |

| LAMIACEAE | ||

| Volkameria inermis L. (=Clerodendrum inerme (L.) Gaertn.) | ||

| CIP-29 | TMV, PRSV, SHMV | [111,112] |

| Volkameria aculeata L. (=Clerodendrum aculeatum (L.) Schltdl.) | ||

| CA-SRI (CAP-34) | TMV, SHMV, PRSV | [113,114,115] |

| ADOXACEAE | ||

| Sambucus nigra L. | ||

| SNAI’ | TMV | [116] |

| Nigrin b (SNAV) | TMV | [76] |

| Virus | Target | RIP | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| RIPs alone | |||

| HIV | HIV infected cells | TCS | [61,157,158] |

| SHIV | SHIV infected cells | Maize RIP | [27] |

| PEGylated RIPs | |||

| HSV-1 | HIV infected cells | α-MMC | [40] |

| HIV infected cells | MAP30 | [40] | |

| Immunotoxins | |||

| HIV | gp 120 | RAC, PAP-S, PAC, Gelonin | [168,169,170,171,172] |

| gp 41 | RAC, PAC, Gelonin | [170,171,172,173,174,175] | |

| gp 160 | RAC | [173] | |

| CD45RO | RAC | [176] | |

| CD4 | PAP | [143,177] | |

| CD25 | RAC | [178] | |

| PICV | PICV | Gelonin | [31] |

| EBV | CD30 | Saporin 6 | [163] |

| EBV/C3d receptor | Gelonin | [164] | |

| MCMV | MCMV | RAC | [165,179] |

| Conjugates | |||

| HIV | gp 120 | RAC | [166] |

| CD8+ T-cells | Saporin | [49] | |

| Engineered proteins | |||

| HIV | HIV protease | RAC | [29] |

| HIV protease | Maize RIP | [28] | |

| CHIKV | Viral life cycle | PAP | [53] |

| DENV | Viral life cycle | MAP30 | [42] |

| HBV | HBV infected cells | RAC-PAP | [167] |

| Nanocapsules | |||

| HIV | HIV infected cells | MAP30 | [180] |

| HIV protease | RAC | [181] |

| RIP | Host | Virus | Protection | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRIP | Nicotiana tabacum | TMV, TEV | 73% L.L. | [77] |

| IRAb | Nicotiana tabacum | TMV, TEV | 54% L.L. | [77] |

| Curcin 2 | Nicotiana tabacum | TMV | 9 D.D. | [78] |

| Trichosanthin | Nicotiana tabacum | TuMV | 100% L.L. | [79] |

| Nicotiana tabacum | TMV, CMV | 14 D.D. | [80] | |

| Lycopersicon esculentum | TMV, CMV | 100% L.I.P. | [187] | |

| Cassin | Nicotiana tabacum | TMV | 13 D.D. | [83] |

| Dianthin 30 | Nicotiana benthamiana | ACMV | 100% L.L. | [84] |

| PIP | Solanum tuberosum | PVY, PYX, PLRV | 98% L.V.L | [99] |

| PAP | Nicotiana tabacum | PVY, PYX, CMV | 100% L.I.P. | [102,188] |

| Nicotiana benthamiana | PVY | 67% L.I.P. | [102] | |

| Solanum tuberosum | PVY, PYX | 84% L.I.P. | [102] | |

| PAPII | Nicotiana tabacum | TMV, PVX | 89% L.L. | [104] |

| SNAI’ | Nicotiana tabacum | TMV | 59% L.L. | [116] |

| Nigrin b (SNAV) | Nicotiana tabacum | TMV | 43% L.L. | [76] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Citores, L.; Iglesias, R.; Ferreras, J.M. Antiviral Activity of Ribosome-Inactivating Proteins. Toxins 2021, 13, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins13020080

Citores L, Iglesias R, Ferreras JM. Antiviral Activity of Ribosome-Inactivating Proteins. Toxins. 2021; 13(2):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins13020080

Chicago/Turabian StyleCitores, Lucía, Rosario Iglesias, and José M. Ferreras. 2021. "Antiviral Activity of Ribosome-Inactivating Proteins" Toxins 13, no. 2: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins13020080

APA StyleCitores, L., Iglesias, R., & Ferreras, J. M. (2021). Antiviral Activity of Ribosome-Inactivating Proteins. Toxins, 13(2), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins13020080