“Two Cultures in Favor of a Dying Patient”: Experiences of Health Care Professionals Providing Snakebite Care to Indigenous Peoples in the Brazilian Amazon

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Characteristics of the Participants

2.2. HCPs’ General Perceptions of Indigenous Peoples

“I had to attend to a snakebite patient and I needed to travel by boat to the community. Another indigenous person who was nearby took possession of our boat because he wanted to be a boatman and told me that if I got on the boat without him, he would shoot me.” (AM, FGD1, P1)

“Yes, they are really strong, I’ve never… I’ve never seen a human being as strong as the indigenous.” (AM, FGD2, P3)

“They are wonderful, right? They (the Pirahã) are an ethnic group, a people that you fall in love with. I think that all professionals, if they could spend at least two months there, I think it would be enriching. It would even change your point of view of life.” (AM, FGD2, P2)

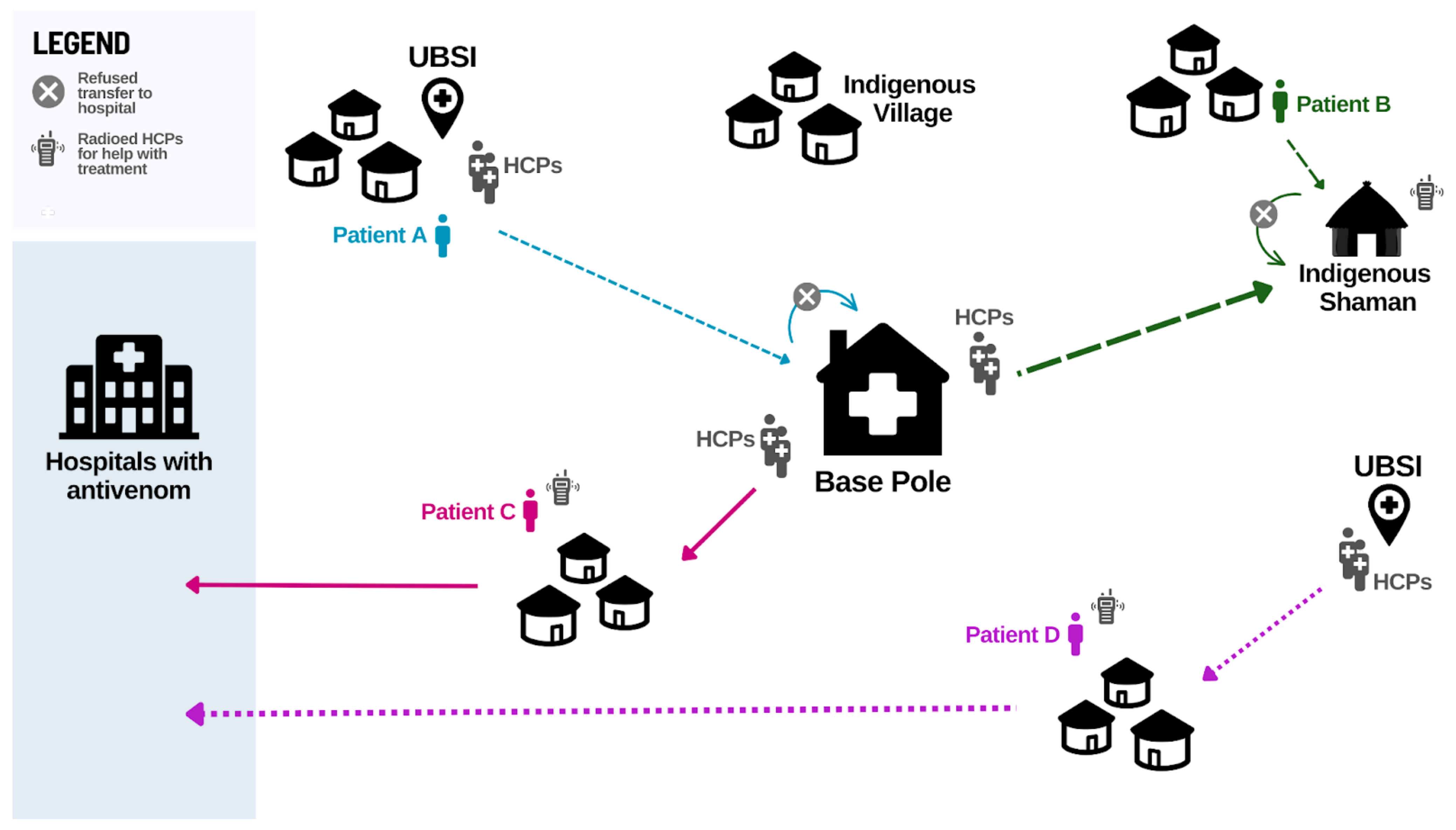

2.3. Care Pathways at the Intersection of the Professional and Indigenous Sectors

“If you look at the flowchart in 90% of the communities, the care flowchart would be… first it is traditional treatment at home. Second, [traditional treatment] didn’t work out, so he goes to look for a pajé in the villages that have a shaman; the shaman is the pajé. And then he goes to look for the pastor, and, as a last resort, he goes to the base hub.” (AM, FGD3, P8)

“Many times, it’s agonizing. You see, you have to wait, but it’s that eternal agony, you’re like ‘I want to help, I want to use my medicine, the medicine that we studied,’ but we have to respect them [their practices].” (AM, FGD4, P7)

2.4. Health Logistics within the Professional Sector

“I’ve had situations where we transported a patient two days after the bite, and sometimes it’s not because of [the patient] refusing [to leave the community], it’s not because of cultural issues, as colleagues mentioned. It is very much because of the logistics.” (AM, FGD3, P8)

“It’s difficult for us to win over the indigenous person so that they can come to the city for treatment, but then when you spend two, four, six hours [in the community] to win him over, when you win, you [submit the] request transport. And transport is only aerial. It takes five days of travel to get there in the flood season and seven days in the dry season, so transport is only by air. And then, when I manage to get an indigenous person to go, he has to take the whole family, everyone together… And then [the aircraft] takes two or three days to get here and [waiting] makes them give up.” (AM, FGD2, P8)

“Nearby units either don’t have it (medicine) or say they don’t have it, because [if] you have your patient and you give [the medicine] to my patient, [you could] lose yours. So, they don’t want to give it to us, because the moment it happens to them... And nobody knows the moment, they won’t have [the medicine].” (AM, FGD4, P4)

“The base hub where I work still has the Internet, for now, but sometimes it goes a week without it, it goes five days without it… To work properly, you send the notification immediately after use [of a medication] and then you receive the replacement, right? And [without Internet]... this can be much slower.” (AM, FGD1, P5)

“We don’t have a room for the patient to be admitted. We only have the support house, and sometimes we don’t even have a place for the patient to lie down, well-accommodated. I’ve had to cover the floor with a sheet or a simple towel.” (RR, FGD1, P5)

“That’s what I was going to ask (name of other participant), if she has a life, because even when I’m off duty, I can’t have a life. Because, unfortunately, we are all they have.” (AM, FGD1, P3)

“We are primary care workers. We are not authorized to do procedures other than primary care, but sometimes we do it because there is no one else to do it.” (RR, FGD1, P8)

“In addition to the risks of being bitten by snakes, by jaguars, or other accidents that can happen, that we walk under, the ones in the forest, we also have risks at night. Because at the [Base] hub, they always… knock on the window, or when we are sleeping in the shack they (indigenous peoples) knock on the door and call from afar. They keep calling my name, right? Then we leave at any time [and have to travel at night]… We are already sleeping in our uniform for when [the villager] calls. We already know.” (AM, FGD2, P3)

“Currently, our biggest difficulty is the lack of communication, because in the indigenous region there are some communities that have Internet, but not all of them, and our only means of communication is community radio. There are communities that don’t even have community radio and communication gets very complicated when a snakebite occurs. It takes a long time for the population to be able to ask for help and then get help for a patient” (RR, FGD1, P7)

2.5. Conflicts between the Professional and Indigenous Sectors

“Yanomâmi territory does not see this issue of the geographic area of the states, but that makes a difference for us. So, if there is a case in the Amazonas, and I have the serum here, I cannot say [to the indigenous people] that I will not give the serum because the serum is from Roraima and Amazonas has to give the serum” (RR, FGD2, P2).

“You have to create a bond, because if you don’t create a bond, they won’t go to you. That’s why I went back to my base hub.” (AM, FGD3, P2)

“Yeah, and they don’t let the team in there, all of a sudden, because of the bond, the great staff turnover within the DSEI, right? In the villages, today it is me, tomorrow it can be someone else, the day after tomorrow it is someone else.” (AM, FGD3, P1)

“What I wanted to convey is the importance of having the snakebite antivenom, of us having a [positive] solution. We need to be effective, because if he sees that I treated that person and that person died by accident, they won’t believe me anymore, understand?” (AM, FGD3, P3)

“The antivenom was four hours away by speedboat, but it all happened at night and the guy died there. We have nothing to do, right? What are we going to do? We can’t get out of there. It’s very far and then they start to pressure us. The people say ‘But you don’t provide assistance.’ They really blame us, [and say] ‘You let my son die, you let my father die.’” (AM, FGD2, P4)

“23 ethnicities, so 23 different cultures…The language is different, and for me, so far, I couldn’t get all the ethnicities... So, we have 23 difficulties in interacting, precisely because work planning doesn’t account for this and I get something new every year, every month.” (AM, FGD3, P1)

“I think we all do this. When we come in, we study the epidemiology of the place, the behavior… even for our clothes. Sometimes, I ask my bosses, ‘Where am I going to go?’ He says, ‘Does it matter?’ I say yes, because, depending on the place, even our clothes, what we are going to take is different.” (AM, FGD1, P1)

“There are ethnicities that are more imposing, aggressive, violent, others are not. There are ethnicities that attribute, for example, illness or death to the team. There are ethnicities that do not even seek care. There are ethnic groups that trust their traditional knowledge more than the team, no matter how much we’ve done there, you know? It’s as diverse as you can imagine.” (AM, FGD1, P5)

“This [patient] was a Hupda. Members of this indigenous ethnicity do not accept a woman touching him if he has been subjected to a snakebite, because, in their culture, if a woman is menstruating, she is unclean and he will die.” (AM, FGD3, P3)

“When the nurse is a woman, they want to intimidate. When it’s a team of men, they put themselves in their place; but, when it’s a team of women, they want to... really intimidate.” (AM, FGD1, P3)

“My first experience was... I was more scared than the patient, because I had arrived at the DSEI in the base hub and the patient had been bitten. He didn’t present anything, super mild symptoms, just a local pain, and I was desperate without knowing what to do.” (AM, FGD4, P5)

“I ended up learning to deal with everything, but the first time I was desperate, because you have a patient in your hands and you look at the nursing technician and the technician is you. [Then], the second time, more or less, the third time, it’s already becoming routine.” (AM, FGD4, P4)

2.6. HCPs’ Perceptions of Indigenous Amenability to Professional Care

“They always arrive with some herbs on the wound. There are a lot of snakebite cases at the clinic because the indigenous people already know that it is a serious thing and that their traditional medicine alone will not solve it. Need to accept western medicine.” (RR, FGD2, P5)

“They even found out I was here, and the indigenous people called me, right? Asking if I was going to come in with the antivenom. It’s because they don’t want to come to the city. They don’t like the cultural clashes of coming to the city.” (AM, FGD2, P4)

2.7. HCPs’ Recommendations for Improving Professional Care of Indigenous Patients

“I get along very well with the shamans, because I’ve been working with the ethnic group (Huni Kuin) for two years. So, it’s me and the shamans. We create bonds like this. First, he comes in and does the work. I let him do his work, for as long as he needs. Then he goes and says, ‘Doctor, now it’s up to you.’ … And today, what interferes the most is that they don’t want to leave the... the village, but other than that, my work and the shamans’ work, my work after the shaman leaves doesn’t interfere with anything.” (AM, FGD2, P8)

“We have to respect it because, for patients, it’s a matter of their millennia of tradition and knowledge. A Yanomâmi girl who we treated for snakebite also wanted to call the shamans and healers. And, in this situation, we had to talk and negotiate to perform our treatment along with their treatment. We had to prove that what we were doing with the patient would benefit him and that what the shaman and the healer were doing would also benefit him. In other words, we united the two beliefs—two cultures in favor of the health of a dying patient.” (RR, FGD1, P5)

“We are fighting for this to become a reality, for it to really happen, so that we can help, so that we can have a faster action, more resolution, in the area where I work… The valley is immense. We have several villages, [and] we’ve lost many patients because there was no plane. Imagine if you go to a village up there and take a boat for ten days, for six days. It’s complicated, so we really need this support in the area to be able to have a better result regarding the cases of ophidian accidents.” (AM, FGD4, P7)

“We have lost children, so this is exactly our greatest anguish. So, when this possibility of decentralization occurs, it is wonderful for us, because we know that if I have a vial of antivenom in (name of region) and [a snakebite] happens… I can do the logistics. But if there is no antivenom in (names of regions), and only in Manaus, then it is difficult.” (AM, FGD4, P4)

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Study Design

5.2. Study Setting

5.3. Research Team and Reflexivity

5.4. Recruitment

5.5. Focus Group Discussion Procedure

5.6. Data Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Snakebite Envenoming—A Strategy for Prevention and Control. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/snakebites/resources/9789241515641/en/ (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Longbottom, J.; Shearer, F.M.; Devine, M.; Alcoba, G.; Chappuis, F.; Weiss, D.J.; E Ray, S.; Ray, N.; A Warrell, D.; de Castañeda, R.R.; et al. Vulnerability to snakebite envenoming: A global mapping of hotspots. Lancet 2018, 392, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Feitosa, E.L.; Sampaio, V.; Salinas, J.L.; Queiroz, A.M.; Da Silva, I.M.; Gomes, A.A.; Sachett, J.; Siqueira, A.; Ferreira, L.C.L.; Dos Santos, M.C.; et al. Older Age and Time to Medical Assistance Are Associated with Severity and Mortality of Snakebites in the Brazilian Amazon: A Case-Control Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, F.H.; Monteiro, W.M.; Da Silva, A.M.M.; Tambourgi, D.V.; Da Silva, I.M.; Sampaio, V.S.; Dos Santos, M.C.; Sachett, J.; Ferreira, L.C.L.; Kalil, J.; et al. Snakebites and scorpion stings in the Brazilian Amazon: Identifying research priorities for a largely neglected problem. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003701. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M.C.; Min, K.-D.; Hamrick, P.N.; Montebello, L.R.; Ranieri, T.M.; Mardini, L.; Camara, V.M.; Luiz, R.R.; Liese, B.; Vuckovic, M.; et al. Overview of snakebite in Brazil: Possible drivers and a tool for risk mapping. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.; Isbister, G.K. Current research into snake antivenoms, their mechanisms of action and applications. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2020, 48, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pucca, M.B.; Cerni, F.A.; Janke, R.; Bermúdez-Méndez, E.; Ledsgaard, L.; Barbosa, J.E.; Laustsen, A.H. History of envenoming therapy and current perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gutiérrez, J.M.; Lomonte, B.; León, G.; Rucavado, A.; Chaves, F.; Angulo, Y. Trends in snakebite envenomation therapy: Scientific, technological and public health considerations. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007, 13, 2935–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, W.M.; Farias, A.S.; Val, F.; Neto, A.V.S.; Sachett, A.; Lacerda, M.; Sampaio, V.; Cardoso, D.; Garnelo, L.; Vissoci, J.R.N.; et al. Providing antivenom treatment access to all brazilian amazon indigenous areas: “every life has equal value”. Toxins 2020, 12, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristino, J.S.; Salazar, G.M.; Machado, V.A.; Honorato, E.; Farias, A.S.; Vissoci, J.R.N.; Neto, A.V.S.; Lacerda, M.; Wen, F.H.; Monteiro, W.M.; et al. A painful journey to antivenom: The therapeutic itinerary of snakebite patients in the Brazilian Amazon (The QUALISnake Study). PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.; Tyburn, B.; Ketterlé, J.; Biao, T.; Mehdaoui, H.; Moravie, V.; Rouvel, C.; Plumelle, Y.; Bucher, B.; Canonge, D.; et al. Prognostic significance of clinical grading of patients envenomed by Bothrops lanceolatus in Martinique. Members of the Research Group on Snake Bite in Martinique. Trans. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1998, 92, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.J.; Scheidt, J.F.H.C.; De Andrade, L.; Rocha, T.A.H.; Fan, H.W.; Monteiro, W.; Palacios, R.; Staton, C.A.; Vissoci, J.R.N.; Gerardo, C.J. Antivenom accessibility impacts mortality and severity of Brazilian snake 2 envenomation: A geospatial information systems analysis. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.S.; Sachett, J.A.G.; Alcântara, J.A.; Freire, M.; Alecrim, M.G.C.; Lacerda, M.; de Lima Ferreira, L.C.; Fan, H.W.; de Souza Sampaio, V.; Monteiro, W.M. Snakebites as cause of deaths in the Western Brazilian Amazon: Why and who dies? Deaths from snakebites in the Amazon. Toxicon 2018, 145, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucca, M.B.; Bernarde, P.S.; Rocha, A.M.; Viana, P.F.; Farias, R.E.S.; Cerni, F.A.; Oliveira, I.S.; Ferreira, I.G.; Sandri, E.A.; Sachett, J.; et al. Crotalus durissus ruruima: Current knowledge on natural history, medical importance, and clinical toxinology. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 659515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.C.; Vuckovic, M.; Montebello, L.; Sarpy, C.; Huang, Q.; Galan, D.I.; Min, K.-D.; Camara, V.; Luiz, R.R. Snakebites in rural areas of Brazil by race: Indigenous the most exposed group. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Os indígenas no Censo Demográfico 2010: Primeiras considerações com base no quesito cor ou raça. 2012. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/indigenas/indigena_censo2010.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Salazar, G.K.M.; Cristino, J..S.; Silva-Neto, A.V.; Farias, A.S.; Alcântara, J.A.; Machado, V.A.; Murta, F.; Sampaio, V.S.; Val, F.; Sachett, A.; et al. Snakebites in “Invisible Populations”: A cross-sectional survey in riverine populations in the remote western Brazilian Amazon. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009758. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.M.; Colombini, M.; Moura-da-Silva, A.M.; Souza, R.M.; Monteiro, W.M.; Bernarde, P.S. Ethno-knowledge and attitudes regarding snakebites in the Alto Juruá region, Western Brazilian Amazonia. Toxicon 2019, 171, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, A. Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture: An Exploration of the Borderland between Anthropology, Medicine, and Pyschiatry; University of California Press: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Moraes, E.B.; Dal Fabbro, D.R.; Oliveira, L.B.; Leão, E.R. Pain Management of Amazon Indigenous Peoples: A Community-Based Study. J. Pain Res. 2021, 14, 1969–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffinen, C.Z.; Sabidó, M.; Díaz-Bermúdez, X.P.; Lacerda, M.; Mabey, D.; Peeling, R.W.; Benzaken, A.S. Point-of-care screening for syphilis and HIV in the borderlands: Challenges in implementation in the Brazilian Amazon. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silva, D.M.; Nascimento, E.H.S.; Santos, L.A.; Martins, N.V.N.; Sousa, M.T.; Figueira, M.C.S. Dificuldades enfrentadas pelos indígenas durante a permanência em uma Casa de Saúde Indígena na região Amazônica/Brasil. Saude Soc. 2016, 25, 920–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grenfell, P.; Fanello, C.I.; Magris, M.; Goncalves, J.; Metzger, W.G.; Vivas-Martínez, S.; Curtis, C.; Vivas, L. Anaemia and malaria in Yanomami communities with differing access to healthcare. Trans. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2008, 102, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A.M.; Leite, M.S.; Langdon, E.J.; Grisotti, M. The challenge of providing primary healthcare care to indigenous peoples in Brazil. Rev. Panam Salud Publica 2018, 42, e184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fan, H.W.; Monteiro, W.M. History and perspectives on how to ensure antivenom accessibility in the most remote areas in Brazil. Toxicon 2018, 151, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça-da-Silva, I.; Tavares, A.M.; Sachett, J.; Sardinha, J.F.; Zaparolli, L.; Santos, M.F.G.; Lacerda, M.; Monteiro, W.M. Safety and efficacy of a freeze-dried trivalent antivenom for snakebites in the Brazilian Amazon: An open randomized controlled phase IIb clinical trial. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0006068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beck, T.P.; Tupetz, A.; Farias, A.S.; Silva-Neto, A.; Rocha, T.; Smith, E.R.; Murta, F.; Dourado, F.S.; Cardoso, D.; Ramos, T.A.; et al. Mapping of clinical management resources for snakebites and other animal envenomings in the Brazilian Amazon. Toxicon X 2022, 16, 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, G.D.S.; Farias, A.S.; Alcântara, J.A.; Machado, V.A.; Murta, F.; Val, F.; Cristino, J.S.; Santos, A.C.; Ferreira, M.B.; Marques, L.; et al. Validation of a culturally relevant snakebite envenomation clinical practice guideline in Brazil. Toxins 2022, 14, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herndon, C.N.; Uiterloo, M.; Uremaru, A.; Plotkin, M.J.; Emanuels-Smith, G.; Jitan, J. Disease concepts and treatment by tribal healers of an Amazonian forest culture. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santos, R.V.; Welch, J.R.; Pontes, A.L.; Garnelo, L.; Cardoso, A.M.; Coimbra, C.E.A., Jr. Health of Indigenous Peoples in Brazil: Inequities and the Uneven Trajectory of Public Policies. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://oxfordre.com/publichealth/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.001.0001/acrefore-9780190632366-e-33;jsessionid=ACEE147C1914EA579741F750A2A73553 (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Allen, L.; Hatala, A.; Ijaz, S.; Courchene, E.D.; Bushie, E.B. Indigenous-led health care partnerships in Canada. CMAJ 2020, 192, E208–E216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunu, W.N.; Makhado, L.; Mabunda, J.T.; Lebese, R.T. Developing strategies for integrating indigenous health and modern health systems for improved adolescent sexual health outcomes in umguza and mberengwa districts in Zimbabwe. Health Serv. Insights 2021, 14, 11786329211036018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlberg, B.M. Integrated Health Care Systems and Indigenous Medicine: Reflections from the Sub-Sahara African Region. Front. Sociol. 2017, 26, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carrie, H.; Mackey, T.K.; Laird, S.N. Integrating traditional indigenous medicine and western biomedicine into health systems: A review of Nicaraguan health policies and Miskitu health services. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pontes, A.L.M.; Santos, R.V. Health reform and Indigenous health policy in Brazil: Contexts, actors and discourses. Health Policy Plan. 2020, 35, i107–i114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussalleu, A.; King, N.; Pizango, P.; Ford, J.; Carcamo, C.P.; IHACC Research Team; Harper, S.L. Nuya kankantawa (we are feeling healthy): Understandings of health and wellbeing among Shawi of the Peruvian Amazon. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 281, 114107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, P.C.; Coimbra, C.E.A.; Welch, J.R.; Alves, L.C.C.; Santos, R.V.; Camacho, L.A.B. Tuberculosis among the Xavante Indians of the Brazilian Amazon: An epidemiological and ethnographic assessment. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2010, 37, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sánchez, A.I.; Rubiano-Mesa, Y.L. Meanings of “Tuberculosis” in Rural Indigenous Communities from a Municipality in the Colombian Amazon. Investig. Educ. Enferm. 2017, 35, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kitzinger, J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ 1995, 311, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, D.R. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Magalhães, S.F.V.; Peixoto, H.M.; Moura, N.; Monteiro, W.M.; Oliveira, M.R.F. Snakebite envenomation in the Brazilian Amazon: A descriptive study. Trans. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 113, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distrito Sanitário Especial Indígena—Ministério da Saúde. Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/composicao/sesai/estrutura/dsei (accessed on 26 January 2023).

- Ministério da Saúde. Política Nacional de Atenção à Saúde dos Povos Indígenas. 2002. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/politica_saude_indigena.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2023).

- Carter, N.; Bryant-Lukosius, D.; DiCenso, A.; Blythe, J.; Neville, A.J. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2014, 41, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Participants from Boa Vista, Roraima (n = 27) 1 | Participants from Manaus, Amazonas (n = 29) | Total Participants (n = 56) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 11 (41%) | 15 (52%) | 26 (46%) |

| Profession | |||

| Physician | 2 | 11 | 13 |

| Nurse | 14 | 18 | 32 |

| Nursing technician | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Veterinarian 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Biologist 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Ethnicities named in transcripts | Apurinã, Baniwa, Baré, Kokama, Hixkaryana, Huni Kuin, Hupda, Hupdes, Kanamari, Korubo, Kulina Pano, Macuxi, Marubo, Matis, Matsés, Paumari, Pirahã, Sateré-Mawé, Suruhuarrá, Tariano, Tenharim, Tsohom-dyapa, Tukano, Yamamadi, Yanomami | ||

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| 1. HCPs’ general perceptions of indigenous peoples | |

| 2. Care pathways at the intersection of professional and indigenous sectors | 2.a. HCPs’ perceptions of indigenous medicine for SBEs 2.b. Narrative of the care pathways of indigenous patients |

| 3. Health logistics within the professional sector | 3.a. Lack of transportation resources 3.b. Communication network failures 3.c. Insufficient medical supplies 3.d. Lack of human resources 3.e. Poor infrastructure of health facilities 3.f. Health risks or personal risks to HCPs |

| 4. Conflicts between the professional and indigenous sectors | 4.a. Issues arising from the misalignment between official borders 4.b. Importance of trust with indigenous communities 4.c. Short rotations and high turnover 4.d. Inability of HCPs to provide effective treatment 4.e. Lack of intercultural training for HCPs 4.f. Influence of diversity on HCP care delivery |

| 5. HCPs’ perceptions of indigenous peoples in relation to the acceptability of professional care | 5.a. Indigenous peoples’ amenability to receiving antivenom 5.b. Indigenous resistance to leaving their communities |

| 6. HCPs’ recommendations for improving professional care of indigenous patients | 6.a. Joint, bicultural approach to SBE treatment 6.b. Decentralizing antivenom to non-urban health facilities |

| Resistance to Hospitals | Illustrative Quote(s) |

|---|---|

| Spiritual beliefs regarding reincarnation | “She was coming from the field, but she was on the way, almost arriving home… She died. She came crawling to try to get there alive, desperate, without letting anyone touch her to get home. Why? Because they believe that if they die outside their home, their environment, their land, where they live… they, if they reincarnate, they will come as beings of the forest. They will not come in the afterlife to the physical human body. So, they cannot die outside [their lands] because they want to come back the same way.” (AM, FGDV, P3) |

| Fear of death | “They don’t like to go to the city at all. For them, it is, they think that if they go there, usually when they go it’s because they are already very critical patients, and they often don’t come back. They come back in the coffin. That’s why they’re so afraid to go to the city.” (AM, FGDM, P2) |

| Fear of amputation | “The reason they don’t like coming to the city is that they assimilate the city to the compartment syndrome. So, they say, ‘I don’t want to go. I want to treat myself here, because they’ll take my foot. They’ll take my leg. I’ll come back all cut.’ Our difficulty to get them out of there for treatment is that, because they can’t understand, right, this process… this negative evolution of the snakebite. So, they’re afraid of compartment syndrome, and sometimes they get compartment syndrome because they don’t go, and we don’t get access. The shaman goes there, the shaman sometimes sucks the area, makes a tourniquet, puts everything you can imagine on the skin that makes our work difficult, they do it. And you only have access after all possibilities are over.” (AM, FGDM, P8) “[It is] complex for them (amputees) to come back, because they will be rejected. It is as if they have no means of subsistence for themselves, becoming an invalid, and when they get the prosthesis, they also don’t feel well and wonder why they need to use it. And they already imagine that they will suffer rejection in the community, so that’s why they end up not returning to the community anymore.” (RR, FGDW, P2) |

| Cultural food preferences | “Because of these difficulties… we nurses, we got together and went to talk to the municipal health secretary to see if we could make a more cozy environment in the hospital. And we did, [we put] some paintings of the forest [and] put a hammock tie. We talked to the nutritionist at the hospital where the secretary gave support. For example, Pirahã food is just fish thrown in the water and that’s it. If you put black pepper and paprika, they won’t eat it.” (AM, FGDM, P8) |

| State | DSEI # | Area (km2) | Population | Health Care Units | Ethnicities and Villages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amazonas | Vale do Rio Javari | 91,384.29 | 6082 | 21 UBSIs *, 7 base hubs | 8 ethnicities, 66 villages |

| Manaus | 303,092.01 | 31,468 | 5 UBSIs, 17 Base hubs | 48 ethnicities, 263 villages | |

| Médio Rio Solimões and Tributaries | 297,616.37 | 20,867 | 19 UBSIs, 15 base hubs | 21 ethnicities, 186 villages | |

| Alto Rio Negro | 138,020.94 | 27,769 | 5 UBSIs, 25 base hubs | 23 ethnicities, 685 villages | |

| Alto Rio Solimões | 79,763.43 | 70,659 | 15 UBSIs, 12 base hubs | 7 ethnicities, 241 villages | |

| Médio Rio Purus | 105,806.98 | 8770 | 7 UBSIs, 10 base hubs | 11 ethnicities, 123 villages | |

| Parintins | 50,644.96 | 16,582 | 12 UBSIs, 12 base hubs | 11 ethnicities, 127 villages | |

| Amazonas and Roraima | Yanomami | 106,327.56 | 29,934 | 27 UBSIs, 37 base hubs | 2 ethnicities, 370 villages |

| Roraima | Eastern Roraima | 69,755.08 | 55,089 | 245 UBSI, 34 base hubs | 7 ethnicities, 342 villages |

| Question/Theme | Objective |

|---|---|

| Experience with SBEs | |

| Which of you here has seen or treated a person who was a victim of a snakebite? Could you share your experience? Explore answers:

| Assess the confidence level of professionals in the diagnosis and treatment of SBEs. |

| SBE patient itinerary | |

| How do patients who have been bitten by snakes usually arrive at the health facility where you work? Explore answers:

| Understanding SBEs and follow-up by hospital/facility |

| Treatment | |

| What would be the ideal treatment for a snakebite patient? Does it impact your workload? Is there anything that is missing at your current facility in order to provide the best care for patients? If yes, what? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murta, F.; Strand, E.; de Farias, A.S.; Rocha, F.; Santos, A.C.; Rondon, E.A.T.; de Oliveira, A.P.S.; da Gama, H.S.S.; Vieira Rocha, Y.; Rocha, G.d.S.; et al. “Two Cultures in Favor of a Dying Patient”: Experiences of Health Care Professionals Providing Snakebite Care to Indigenous Peoples in the Brazilian Amazon. Toxins 2023, 15, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins15030194

Murta F, Strand E, de Farias AS, Rocha F, Santos AC, Rondon EAT, de Oliveira APS, da Gama HSS, Vieira Rocha Y, Rocha GdS, et al. “Two Cultures in Favor of a Dying Patient”: Experiences of Health Care Professionals Providing Snakebite Care to Indigenous Peoples in the Brazilian Amazon. Toxins. 2023; 15(3):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins15030194

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurta, Felipe, Eleanor Strand, Altair Seabra de Farias, Felipe Rocha, Alícia Cacau Santos, Evellyn Antonieta Tomé Rondon, Ana Paula Silva de Oliveira, Hiran Satiro Souza da Gama, Yasmim Vieira Rocha, Gisele dos Santos Rocha, and et al. 2023. "“Two Cultures in Favor of a Dying Patient”: Experiences of Health Care Professionals Providing Snakebite Care to Indigenous Peoples in the Brazilian Amazon" Toxins 15, no. 3: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins15030194

APA StyleMurta, F., Strand, E., de Farias, A. S., Rocha, F., Santos, A. C., Rondon, E. A. T., de Oliveira, A. P. S., da Gama, H. S. S., Vieira Rocha, Y., Rocha, G. d. S., Ferreira, M., Azevedo Machado, V., Lacerda, M., Pucca, M., Cerni, F., Nickenig Vissoci, J. R., Tupetz, A., Gerardo, C. J., Moura-da-Silva, A. M., ... Monteiro, W. (2023). “Two Cultures in Favor of a Dying Patient”: Experiences of Health Care Professionals Providing Snakebite Care to Indigenous Peoples in the Brazilian Amazon. Toxins, 15(3), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins15030194