Real-Time CO2 Production Monitoring in Stored Oats as an Indicator of Type A Trichothecenes and Ochratoxin A Contamination Under Simulated Environmental Conditions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Fungal Populations and Isolations in Contaminated Oats

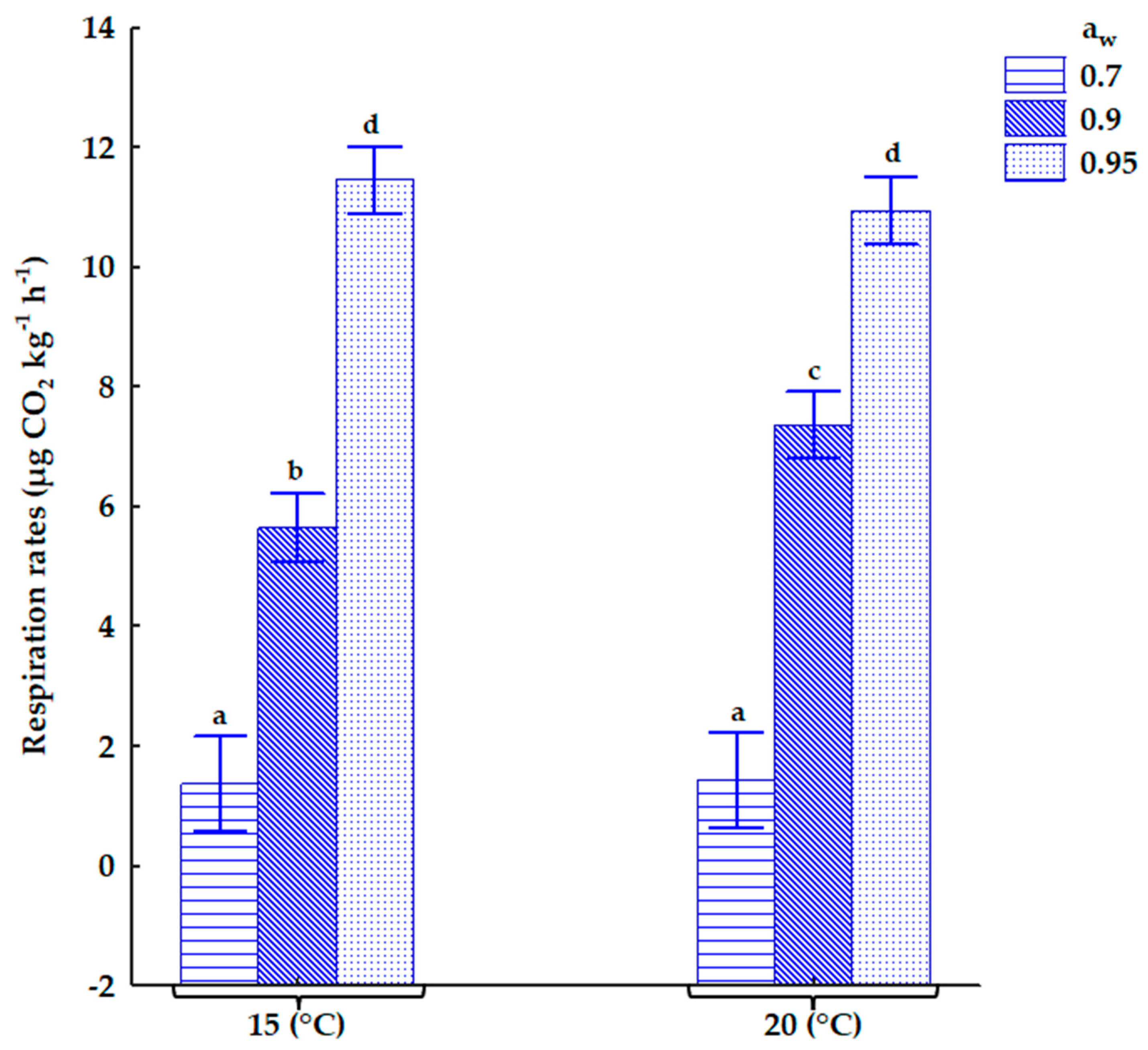

2.2. The Influence of Storage Conditions on Respiration Rates in Contaminated Oats

2.3. Method Validation Performance and the Influence of Storage Conditions on Mycotoxin Concentrations in Contaminated Oats

2.3.1. Method Validation Performance in the Oat Matrix

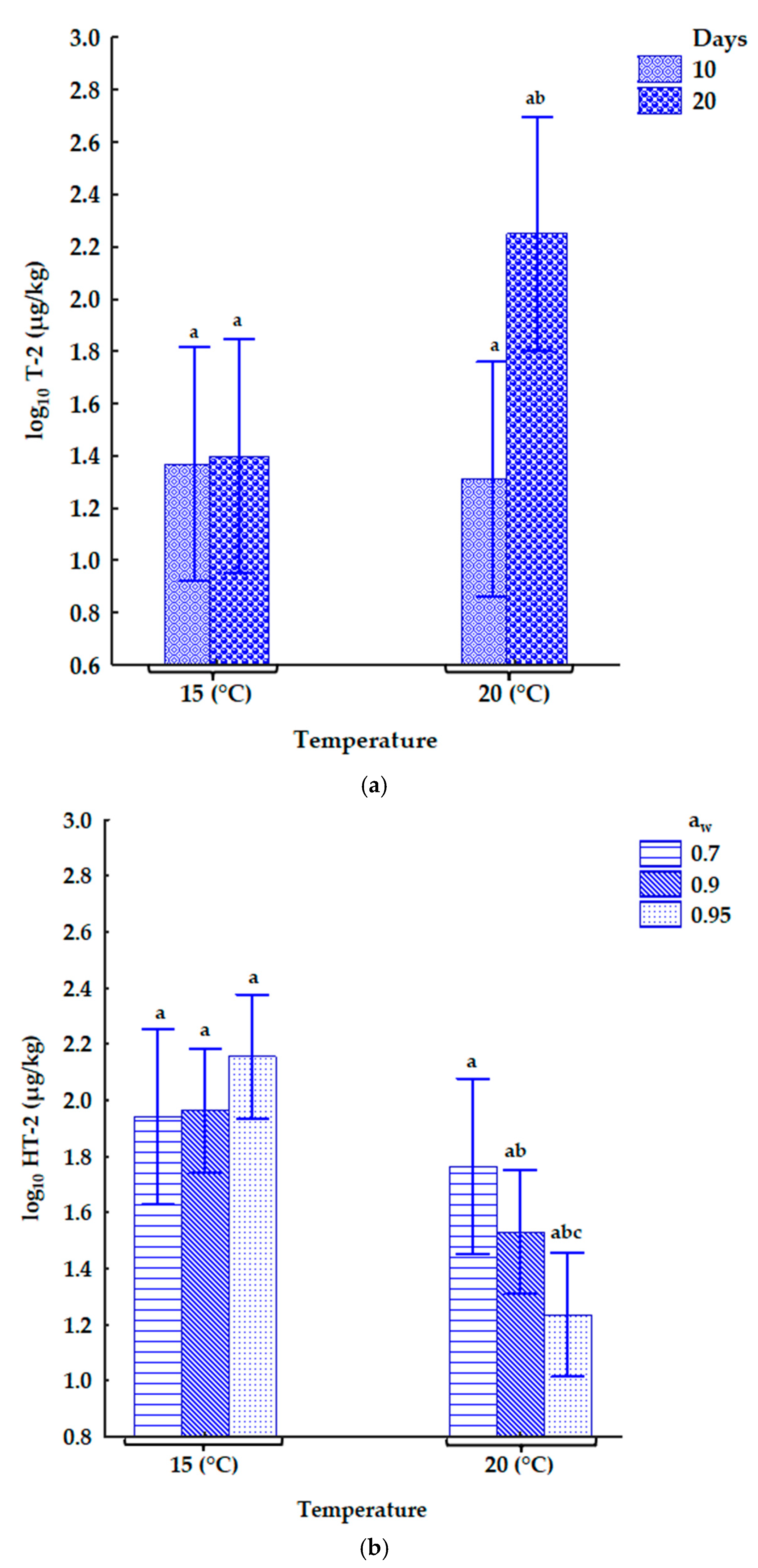

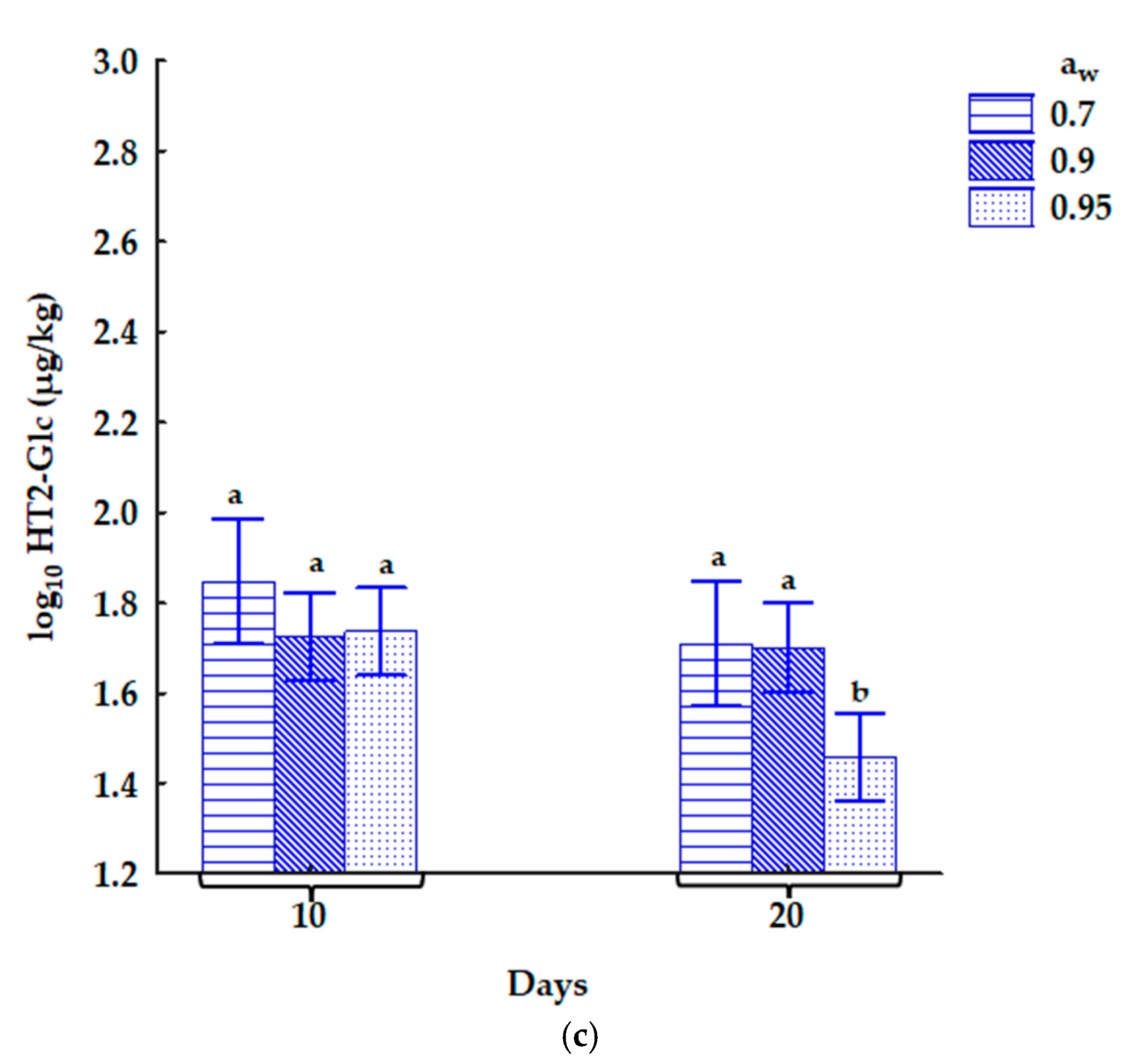

2.3.2. The Influence of Storage Conditions on Mycotoxin Concentrations in the Naturally Contaminated Oats

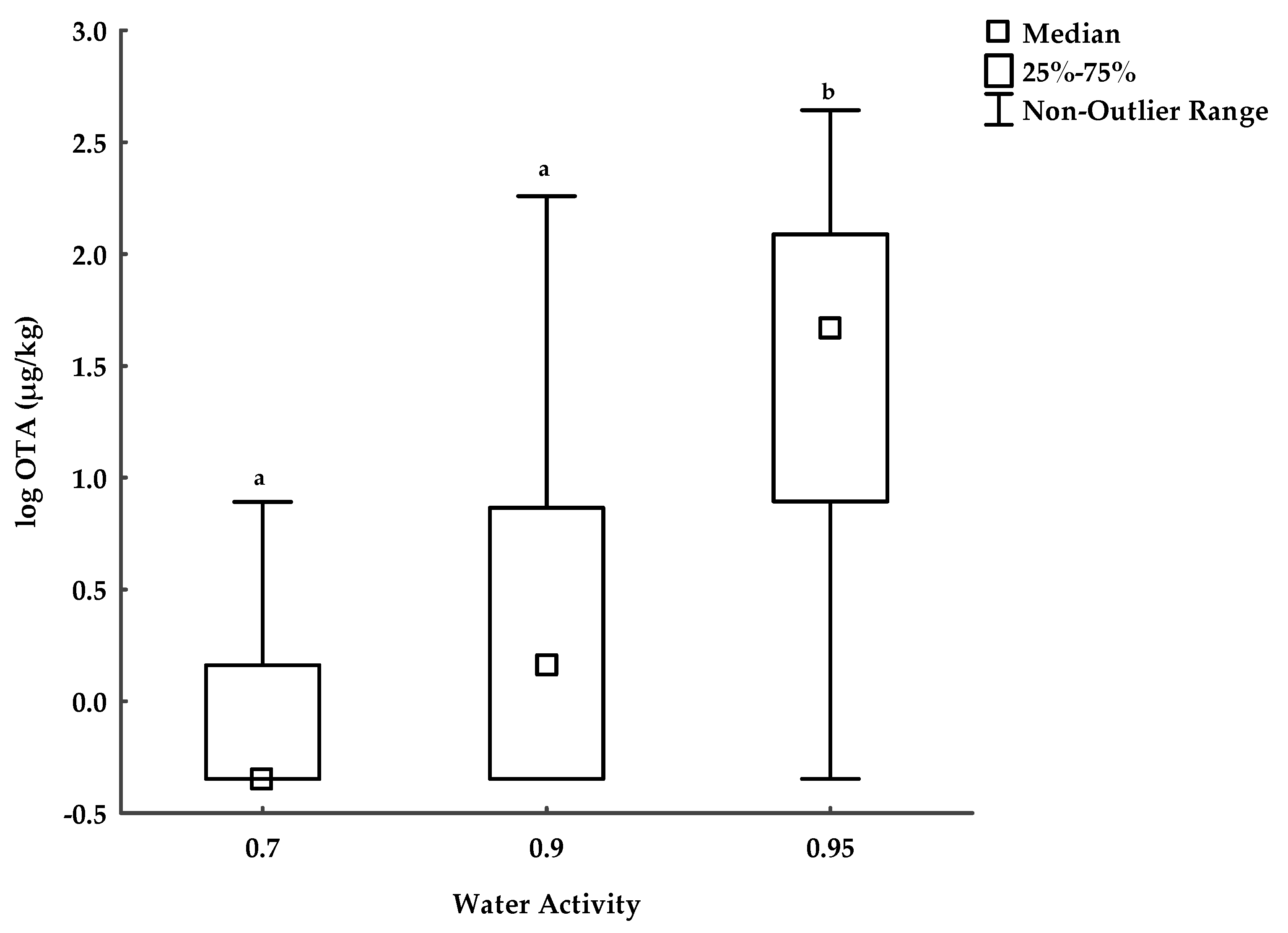

The Influence of Storage Conditions on OTA Concentrations in the Naturally Contaminated Oats

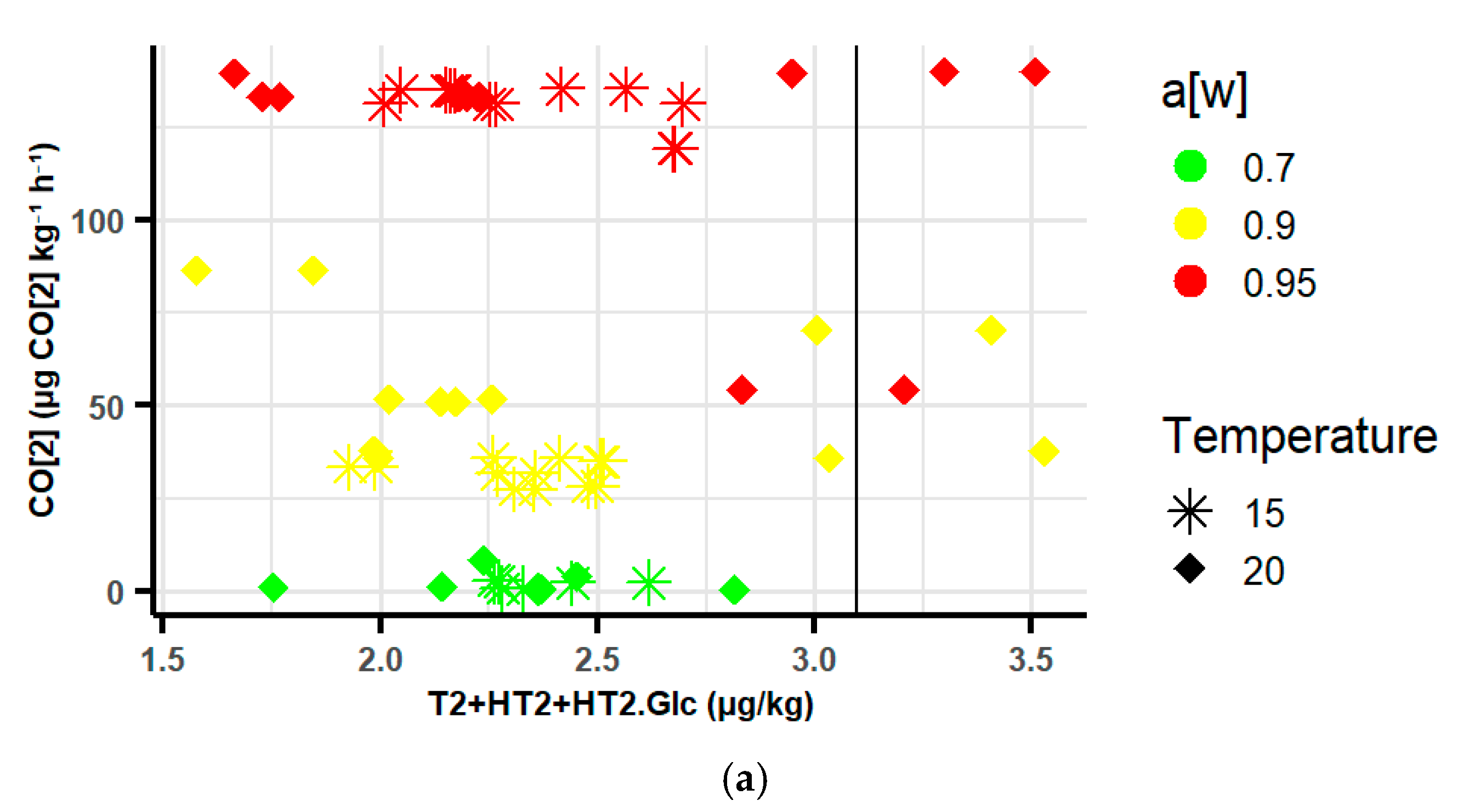

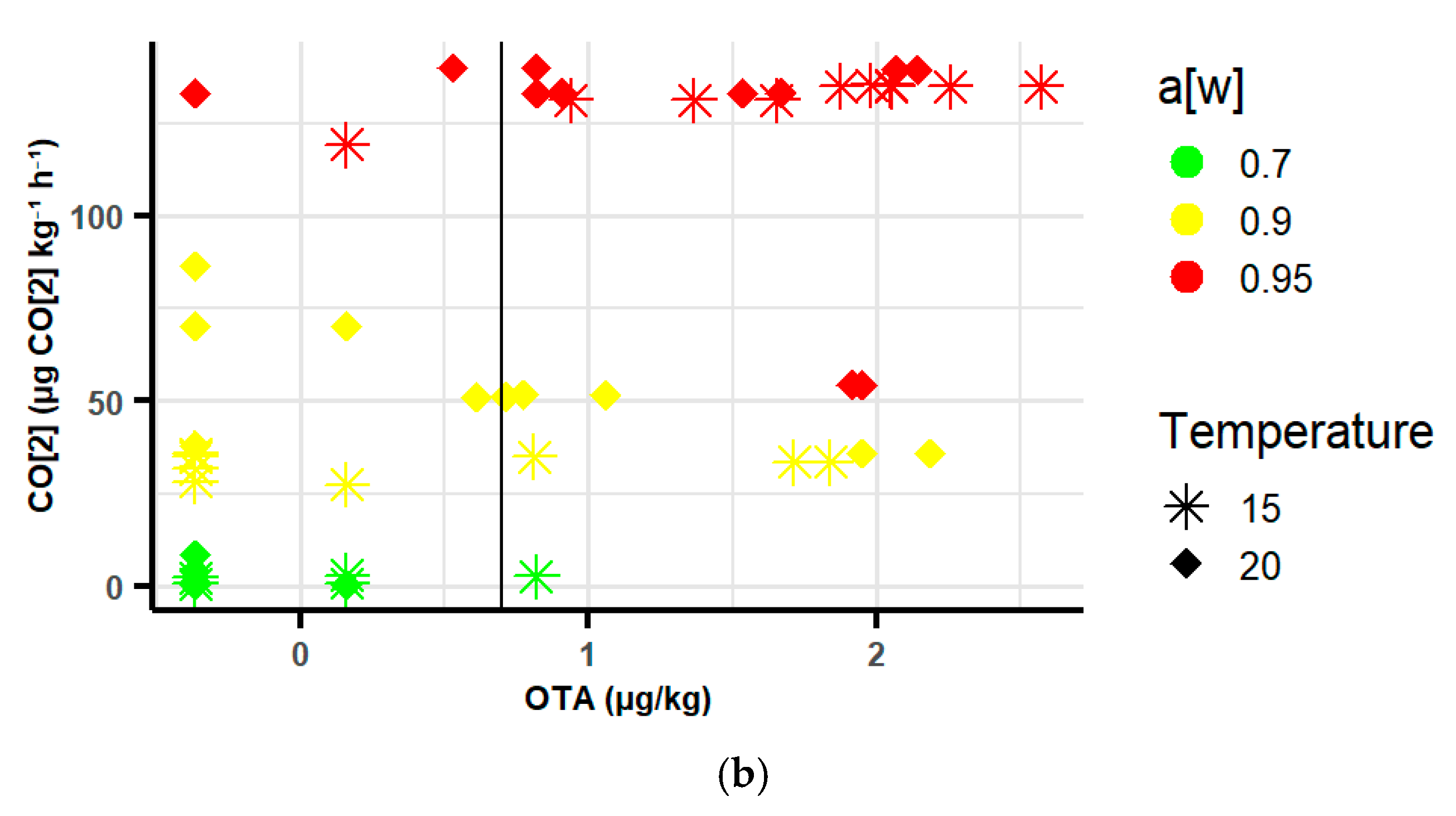

2.3.3. Relationship Between Respiration Rates (RR) and Type A Trichothecenes and Ochratoxins in Oats

3. Discussion

3.1. Respiration Rates in Contaminated Oats

3.2. Type A Trichothecenes in Naturally Contaminated Oats

3.3. OTA in Naturally Contaminated Oats

3.4. Relationship Between CO2 and Mycotoxins in Naturally Contaminated Oats

3.5. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methodology

4.1. Oat Grains and Moisture Adsorption Curve Analysis

4.2. Mini-Silo CO2 Sensing Storage Experiment

4.3. Fungal Populations and Isolations

4.4. Fungal Isolations

4.5. Mycotoxin Analysis

4.5.1. Chemical Reagents

4.5.2. LC-MS/MS

4.5.3. Method Validation

4.5.4. Sample Preparation and Extraction

4.6. Statistical Analyses

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- FMI. Future Market Insights. Oats Market Is Projected to Reach USD 10.8 Billion by 2032-Comprehensive Research Report by FMI. 2022. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2022/02/09/2382216/0/en/Oats-Market-is-projected-to-reach-USD-10-8-Billion-by-2032-Comprehensive-Research-Report-by-FMI.htmL (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Barcchiya, J.; Meena, R.K.; Lal, N. Oat is a multifunctional cereal crop. Innov. Farming 2017, 2, 114–116. [Google Scholar]

- FAO–Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. Global Food Loss Index. 2018. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/a551b26f-6d33-4e3e-ba29-122725ebe464/content (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Cinar, A.; Onbaşı, E. Mycotoxins: The hidden danger in foods. In Mycotoxins and Food Safety; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sacchi, C.; González, H.H.L.; Broggi, L.E.; Pacin, A.; Resnik, S.L.; Cano, G.; Taglieri, D. Fungal contamination and mycotoxin natural occurrence in oats for race horses feeding in Argentina. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2009, 152, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabañes, F.J.; Bragulat, M.R.; Castellá, G. Ochratoxin A producing species in the genus Penicillium. Toxins 2010, 2, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božik, M.; Císarová, M.; Tančinová, D.; Kouřimská, L.; Hleba, L.; Klouček, P. Selected essential oil vapours inhibit growth of Aspergillus spp. in oats with improved consumer acceptability. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 98, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautsalo, J.; Jauhiainen, L.; Hannukkala, A.; Manninen, O.; Veteläinen, M.; Pietilä, L.; Peltoniemi, K.; Jalli, M. Resistance to Fusarium head blight in oats based on analyses of multiple field and greenhouse studies. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 158, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofgaard, I.S.; Aamot, H.U.; Seehusen, T.; Riley, H.; Dill-Macky, R.; Holen, B.M.; Brodal, G. Fusarium and mycotoxin content of harvested grain was not related to tillage intensity in Norwegian spring wheat fields. World Mycotoxin J. 2020, 13, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imathiu, S.M.; Edwards, S.G.; Ray, R.V.; Back, M.A. Fusarium langsethiae—A HT-2 and T-2 toxins producer that needs more attention. J. Phytopathol. 2013, 161, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhungana, B.; Ali, S.; Byamukama, E.; Krishnan, P.; Caffe-TremL, M. Incidence of Penicillium verrucosum in grain samples from oat varieties commonly grown in South Dakota. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81, 898–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarazona, A.; Gómez, J.V.; Mateo, F.; Jiménez, M.; Mateo, E.M. Potential health risk associated with mycotoxins in oat grains consumed in Spain. Toxins 2021, 13, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattanzio, V.M.; Visconti, A.; Haidukowski, M.; Pascale, M. Identification, and characterization of new Fusarium masked mycotoxins, T2 and HT2 glycosyl derivatives, in naturally contaminated wheat and oats by liquid chromatography–high-resolution mass spectrometry. J. Mass. Spectrom. 2012, 47, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthiller, F.; Crews, C.; Dall’Asta, C.; Saeger, S.D.; Haesaert, G.; Karlovsky, P.; Oswald, I.P.; Seefelder, W.; Speijers, G.; Stroka, J. Masked mycotoxins: A review. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) 2024/1038 of 9 April 2024 amending Regulation (EU) 2023/915 as regards maximum levels of T-2 and HT-2 toxins in food. Off. J. Eur. Union 2024, L 94, 1–7. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1038/oj (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Coradi, P.C.; Maldaner, V.; Lutz, É.; da Silva Daí, P.V.; Teodoro, P.E. Influences of drying temperature and storage conditions for preserving the quality of maize postharvest on laboratory and field scales. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 22006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taher, H.; San Martino, S.; Abadia, M.B.; Bartosik, R.E. Respiration of barley seeds (Hordeum vulgare L.) under different storage conditions. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2023, 104, 102178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, A.; Magan, N. Comparisons of water activity and temperature impacts on growth of Fusarium langsethiae strains from northern Europe on oat-based media. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 142, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Jia, B.; Li, K.; Zhou, H.; Lai, W.; Tang, Y.; Yan, Z.; Sun, W.; Liu, N.; Yu, D.; et al. Pre-warning of abiotic factors in maize required for potential contamination of Fusarium mycotoxins via response surface analysis. Food Control 2021, 121, 107570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulongne-Oriol, M.; Garcia, M.A.; Mahmoud, R.; Bancal, M.O.; Bancal, P.; Bernillon, S.; Pinson-Gadais, L.; Richard-Forget, F. Ecophysiological Behaviour of Major Fusarium Species In Response To Combinations Of Temperature And Water Activity Constraints. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, R.P. Integrated approach on stored grain quality management with CO2 monitoring—A review. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2022, 96, 101950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, H.B.; Armstrong, P.R.; Maghirang, R.G. Simultaneous monitoring of stored grain with relative humidity, temperature, and carbon dioxide sensors. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2009, 25, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Danao, M.G.; Rausch, K.; Singh, V. Diffusion and production of carbon dioxide in bulk corn at various temperatures and moisture content. In Proceedings of the 2013, Kansas City, MI, USA, 21–24 July 2013; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2013; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Danao, M.G.C.; Zandonadi, R.S.; Gates, R.S. Development of a grain monitoring probe to measure temperature, relative humidity, carbon dioxide levels and logistical information during handling and transportation of soybeans. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2015, 119, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudienė, E.; Rušinskas, D.; Balčiūnas, G.; Juodeikienė, G.; Gailius, D. Carbon dioxide respiration rates in wheat at various temperatures and moisture contents. Mapan 2017, 32, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylona, K.; Sulyok, M.; Magan, N. Relationship between environmental factors, dry matter loss and mycotoxin levels in stored wheat and maize infected with Fusarium species. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2012, 29, 1118–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Cela, E.; Kiaitsi, E.; Sulyok, M.; Medina, A.; Magan, N. Fusarium graminearum in stored wheat: Use of CO2 production to quantify dry matter losses and relate this to relative risks of zearalenone contamination under interacting environmental conditions. Toxins 2018, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oluwakayode, A.; Sulyok, M.; Krska, R.; Medina, A. The effect of the interactions of water activity, and temperature on OTA, OTB, and OTα produced by Penicillium verrucosum in a mini silo of natural and inoculated wheat using CO2 production as fungal activity sentinel. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/808 of 22 March 2021 on the performance of analytical methods for residues of pharmacologically active substances used in food-producing animals and on the interpretation of results as well as on the methods. Off. J. Eur. Union 2021, 180, 84–109. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915 of 25 April 2023 on maximum levels for certain contaminants in food and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006. Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, 119, 103–157. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/915/oj/eng (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Arcella, D.; Gómez Ruiz, J.A. Use of cut-off values on the limits of quantification reported in datasets used to estimate dietary exposure to chemical contaminants. EFSA Support. Publ. 2018, 15, 1452E. [Google Scholar]

- Oluwakayode, A.; Greer, B.; He, Q.; Sulyok, M.; Meneely, J.; Krska, R.; Medina, A. The influence of different abiotic conditions on the concentrations of free and conjugated deoxynivalenol and zearalenone in stored wheat. Mycotoxin Res. 2024, 40, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chulze, S.N.; Palazzini, J.M.; Lullien-Pellerin, V.; Ramirez, M.L.; Cuniberti, M.; Magan, N. Fusarium species infection in wheat: Impact on quality and mycotoxin accumulation. In Wheat Quality for Improving Processing and Human Health; Igrejas, G., Ikeda, T., Guzmán, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 421–452. [Google Scholar]

- Verheecke-Vaessen, C.; Garcia-Cela, E.; Lopez-Prieto, A.; Jonsdottir, I.O.; Medina, A.; Magan, N. Water and temperature relations of Fusarium langsethiae strains and modelling of growth and T-2 and HT-2 mycotoxin production on oat-based matrices. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 348, 109203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audenaert, K.; Vanheule, A.; Höfte, M.; Haesaert, G. Deoxynivalenol: A major player in the multifaceted response of Fusarium to its environment. Toxins 2013, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijksterhuis, J. Fungal spores: Highly variable and stress-resistant vehicles for distribution and spoilage. Food Microbiol. 2019, 81, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuperlovic-Culf, M.; Vaughan, M.M.; Vermillion, K.; Surendra, A.; Teresi, J.; McCormick, S.P. Effects of atmospheric CO2 level on the metabolic response of resistant and susceptible wheat to Fusarium graminearum infection. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2019, 32, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, D.W.; Lute, A.M.; Gardner, R. Effect of relative humidity on viability, moisture content, and respiration of wheat, oats, and barley seed in storage. J. Agric. Res. 1939, 59, 281–291. [Google Scholar]

- Ramstad, P.E. The Relative Respiratory Rates and Hygroscopic Equilibria of Common And Hull-Less Oats. J. Agric. Res. 1942, 64, 237. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.M. Deterioration of stored grains by fungi. Bot. Rev. 1957, 23, 108–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, M.J.; Dobson, A.D. Molecular biology of mycotoxin biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999, 175, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, A.E. Fusarium Mycotoxins: Chemistry, Genetics and Biology; The American Phytopathological Society: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2006; 260p. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, S.G. Investigation of Fusarium mycotoxins in UK Barley and Oat Production. Project Report No.415; AHDB Cereals & Oilseeds: Stoneleigh, UK, 2007; Available online: https://ahdb.org.uk/investigation-of-fusarium-mycotoxins-in-uk-barley-and-oat-production (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Daud, N.; Currie, V.; Duncan, G.; Filipe, J.A.; Yoshinari, T.; Stoddart, G.; Roberts, D.; Gratz, S.W. Free and modified mycotoxins in organic and conventional oats (Avena sativa L.) grown in Scotland. Toxins 2023, 15, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattanzio, V.M.; Solfrizzo, M.; Visconti, A. Enzymatic hydrolysis of T-2 toxin for the quantitative determination of total T-2 and HT-2 toxins in cereals. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 395, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahla, A.; Verheecke-Vaessen, C.; Delpino-Deelias, M.; Gutierrez-Pozo, M.; Medina, A.; Magan, N.; Doohan, F. Acclimatisation of Fusarium langsethiae, F. poae and F. sporotrichioides to elevated CO2: Impact on fungal growth and mycotoxin production on oat-based media. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 394, 110176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns-Fuller, V.; Aldred, D.; Magan, N. Water, temperature and gas composition interactions affect growth and ochratoxin A production by isolates of Penicillium verrucosum on wheat grain. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 99, 1215–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, E.; Malet, M.; Marín, S.; Sanchis, V.; Ramos, A.J. Effects of water activity and temperature on germination and growth profiles of ochratoxigenic Penicillium verrucosum isolates on barley meal extract agar. International J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 106, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahouar, A.; Marin, S.; Crespo-Sempere, A.; Saïd, S.; Sanchis, V. Influence of temperature, water activity and incubation time on fungal growth and production of ochratoxin A and zearalenone by toxigenic Aspergillus tubingensis and Fusarium incarnatum isolates in sorghum seeds. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 242, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhungana, B.; Ali, S.; Byamukama, E.; Krishnan, P.; Wu, J.; Caffe-Treml, M. Effects of temperature, water activity, and fungal isolate on ochratoxin A accumulation in oat grain inoculated with Penicillium verrucosum and development of a methodology to screen oat cultivars for ochratoxin A accumulation. Cereal Chem. 2019, 96, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, R.A.; Houbraken, J.; Thrane, U.; Frisvad, J.C.; Andersen, B. Food and Indoor Fungi, 2nd ed.; Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Michlmayr, H.; Varga, E.; Malachová, A.; Fruhmann, P.; Piątkowska, M.; Hametner, C.; Šofrová, J.; Jaunecker, G.; Häubl, G.; Lemmens, M.; et al. UDP-glucosyltransferases from rice, Brachypodium, and barley: Substrate specificities and synthesis of type A and B trichothecene-3-O-β-D-glucosides. Toxins 2018, 10, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Fungal Genera | T (°C) | Days | 0.70 aw | 0.90 aw | 0.95 aw | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEA+ | DG18+ | MEA+ | DG18+ | MEA+ | DG18+ | |||

| Fusarium | 15 | 10 | - | - | - | 2.9 ± 2.7 | - | - |

| 20 | 3.3 ± 3.4 | 2.1 ± 2.3 | 3.3 ± 3.3 | 2.7 ± 2.6 | - | - | ||

| 20 | 10 | - | 2.8 ± 2.8 | 2.1 ± 2.3 | 2.6 ± 2.5 | 6.2 ± 6.4 | - | |

| 20 | 4.1 ± 4.0 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Penicillium | 15 | 10 | 3.1 ± 2.9 | - | 2.9 ± 3.1 | 2.8 ± 2.7 | 6.7 ± 6.2 | 6.8 ± 0.0 |

| 20 | 2.9 ± 0.0 | 2.1 ± 2.3 | 3.3 ± 3.4 | 2.9 ± 3 | 7.0 ± 6.6 | 6.9 ± 6.4 | ||

| 20 | 10 | 3.5 ± 3.4 | 3.6 ± 3.5 | 2.9 ± 3.0 | 3.2 ± 3.1 | 6.9 ± 6.2 | 6.9 ± 6.1 | |

| 20 | 3.1 ± 2.8 | 2.9 ± 2.6 | 5.3 ± 5.2 | 5.6 ± 0.0 | 7.0 ± 6.9 | 7.0 ± 6.9 | ||

| Fungal Genera | T (°C) | Days | 0.70 aw | 0.90 aw | 0.95 aw | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEA+ | DG18+ | MEA+ | DG18+ | MEA+ | DG18+ | |||

| Fusarium | 15 | 10 | 7 | 45 | 12 | 24 | - | - |

| 20 | 4 | 43 | 15 | 20 | 11 | - | ||

| 20 | 10 | - | 49 | - | 39 | 11 | - | |

| 20 | - | 49 | - | 64 | 1 | - | ||

| Penicillium | 15 | 10 | 85 | 96 | 83 | 96 | 100 | 100 |

| 20 | 77 | 87 | 81 | 91 | 100 | 100 | ||

| 20 | 10 | 79 | 99 | 81 | 97 | 89 | 100 | |

| 20 | 72 | 97 | 69 | 97 | 68 | 96 | ||

| Aspergillus. sect. Nigri | 15 | 10 | - | 3 | - | - | - | - |

| 20 | 3 | 1 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 20 | 10 | - | - | - | 1 | 17 | 9 | |

| 20 | 3 | - | - | 1 | 33 | 29 | ||

| Aspergillus. sect. Flavi | 15 | 10 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 20 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 20 | 10 | - | - | - | - | 51 | 29 | |

| 20 | - | - | - | - | 73 | 71 | ||

| T °C | Days | 0.70 aw | 0.90 aw | 0.95 aw | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naturally contaminated oats | 15 | 0 | 0.4 ± 0.3 a | 1.9 ± 0.5 b | 8.4 ± 2.3 c |

| 10 | 0.2 ± 0.6 a | 1.9 ± 0.6 b | 34.2 ± 4.0 c | ||

| 20 | 0.2 ± 0.6 a | 2.1 ± 1.9 b | 29.8 ± 0.1 c | ||

| 20 | 0 | 1.3 ± 0.4 a | 10.8 ± 1.0 b | 11.7 ± 2.3 b | |

| 10 | 2.0 ± 1.0 a | 63.0 ± 11.7 b | 133.0 ± 0.0 c | ||

| 20 | 3.4 ± 2.6 a | 48.0 ± 11.1 b | 111.2 ± 28.4 c |

| Components | RA (%) | RSD (%) | RE (%) | SSE (%) | LOD (µg/kg) | LOQ (µg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT-2 toxin | 88 | 7 | 92 | 96 | 4.1 | 13.6 |

| HT-2-glucoside | 97 | 6 | 104 | 93 | 3.9 | 13.2 |

| T-2 toxin | 81 | 9 | 79 | 102 | 3.7 | 12.4 |

| Ochratoxin A | 97 | 17 | 105 | 92 | 0.9 | 2.9 |

| Mycotoxins (µg/kg) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ochratoxin | Type A Trichothecenes | ||||||

| Treatment | T (°C) | Days | aw | OTA | HT-2-Glc | HT-2 | T-2 |

| Naturally contaminated oats | 15 | 10 | 0.7 | <LOQ * | 86.4 ± 41.8 a | 68.4 ± 34.6 a | 71.3 ± 67.1 a |

| 0.9 | <LOQ * | 73.0 ± 24.7 a | 134 ± 35 b | 41.1 ± 22.7 c | |||

| 0.95 | 17.1 ± 16.8 * | 67.2 ± 14.5 a | 231 ± 154 a | 16.9 ± 16.8 b | |||

| 20 | 0.7 | <LOQ * | 61.5 ± 6.5 a | 142 ± 93 a | 62.3 ± 47.3 a | ||

| 0.9 | 24.5 ± 31.2 * | 60.0 ± 14.8 a | 102 ± 73 a | 44.9 ± 24.8 a | |||

| 0.95 | 187 ± 131 * | 44.8 ± 19.2 a | 130 ± 72 b | 18.6 ± 19.1 c | |||

| 20 | 10 | 0.7 | <LOQ * | 62.7 ± 11.3 a | 91.6 ± 54.5 a | 66.5 ± 9.1 a | |

| 0.9 | 5.4 ± 4.9 * | 43.8 ± 17.9 a | 41.3 ± 25.7 a | 27.1 ± 23.5 a | |||

| 0.95 | 19.0 ± 19.5 ** | 47.5 ± 18.4 a | 58.0 ± 43.1 a | 18.1 ± 16.7 b | |||

| 20 | 0.7 | <LOD * | 47.9 ± 27.4 a | 46.8 ± 21.7 a | 224 ± 268 a | ||

| 0.9 | 48.2 ± 65.3 * | 46.1 ± 10.6 a | 36.7 ± 11.1 a | 1281 ± 1335 a | |||

| 0.95 | 86.2 ± 66.7 * | 22.8 ± 11.6 a | <LOD b | 1471 ± 1131 a | |||

| Variable | Correlations. Marked Correlations Are Significant at p < 0.05000 N = 60 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | OTA | HT-2 Toxin | T-2 Toxin | HT-2-Glc | Sum T2HT2HT2GLc | Sum T2HT-2 | |

| CO2 | 1.0000 | 0.5322 | −0.0916 | −0.1931 | −0.2902 | 0.0039 | −0.0192 |

| p = --- | p = 0.000 | p = 0.486 | p = 0.139 | p = 0.025 | p = 0.976 | p = 0.884 | |

| OTA | 0.5322 | 1.0000 | −0.0917 | −0.0763 | −0.2946 | −0.0009 | 0.0483 |

| p = 0.000 | p = --- | p = 0.486 | p = 0.562 | p = 0.022 | p = 0.995 | p = 0.714 | |

| HT-2 toxin | −0.0916 | −0.0917 | 1.0000 | −0.1646 | 0.6274 | 0.0181 | 0.1194 |

| p = 0.486 | p = 0.486 | p = --- | p = 0.209 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.891 | p = 0.364 | |

| T-2 toxin | −0.1931 | −0.0763 | −0.1646 | 1.0000 | −0.1716 | 0.8776 | 0.8708 |

| p = 0.139 | p = 0.562 | p = 0.209 | p = --- | p = 0.190 | p = 0.00 | p = 0.00 | |

| HT-2-Glc | −0.2902 | −0.2946 | 0.6274 | −0.1716 | 1.0000 | −0.0807 | −0.0963 |

| p = 0.025 | p = 0.022 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.190 | p = --- | p = 0.540 | p = 0.464 | |

| Sum T2HT2HT2Glc | 0.0039 | −0.0009 | 0.0181 | 0.8776 | −0.0807 | 1.0000 | 0.9799 |

| p = 0.976 | p = 0.995 | p = 0.891 | p = 0.00 | p = 0.540 | p = --- | p = 0.00 | |

| Sum t2ht2 | −0.0192 | 0.0483 | 0.1194 | 0.8708 | −0.0963 | 0.9799 | 1.0000 |

| p = 0.884 | p = 0.714 | p = 0.364 | p = 0.00 | p = 0.464 | p = 0.00 | p = --- | |

| Mycotoxins | Precursor Ion (m/z) | Product Ion (m/z) | DP (V) | CE (V) | CXP (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-2 toxin | 484.3 | 215.2 | 57 | 29 | 17 |

| 484.3 | 185.1 | 27 | 33 | 11 | |

| HT-2 toxin | 447.4 | 345.1 | 131 | 27 | 20 |

| 442.2 | 323.2 | 50 | 15 | 16 | |

| HT-2-Glucoside | 604.3 | 323.1 | 101 | 17 | 16 |

| 604.3 | 263.1 | 101 | 23 | 14 | |

| Ochratoxin A | 404.0 | 239.0 | 91 | 37 | 16 |

| 404.0 | 102.0 | 102 | 105 | 14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oluwakayode, A.; Sulyok, M.; Berthiller, F.; Verheecke-Vaessen, C.; Krska, R.; Medina, A. Real-Time CO2 Production Monitoring in Stored Oats as an Indicator of Type A Trichothecenes and Ochratoxin A Contamination Under Simulated Environmental Conditions. Toxins 2025, 17, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17030132

Oluwakayode A, Sulyok M, Berthiller F, Verheecke-Vaessen C, Krska R, Medina A. Real-Time CO2 Production Monitoring in Stored Oats as an Indicator of Type A Trichothecenes and Ochratoxin A Contamination Under Simulated Environmental Conditions. Toxins. 2025; 17(3):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17030132

Chicago/Turabian StyleOluwakayode, Abimbola, Michael Sulyok, Franz Berthiller, Carol Verheecke-Vaessen, Rudolf Krska, and Angel Medina. 2025. "Real-Time CO2 Production Monitoring in Stored Oats as an Indicator of Type A Trichothecenes and Ochratoxin A Contamination Under Simulated Environmental Conditions" Toxins 17, no. 3: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17030132

APA StyleOluwakayode, A., Sulyok, M., Berthiller, F., Verheecke-Vaessen, C., Krska, R., & Medina, A. (2025). Real-Time CO2 Production Monitoring in Stored Oats as an Indicator of Type A Trichothecenes and Ochratoxin A Contamination Under Simulated Environmental Conditions. Toxins, 17(3), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17030132