Trogocytosis in Unicellular Eukaryotes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Initial Discovery of Cell Nibbling in Unicellular Eukaryotes

3. General Role of Trogocytosis in Eukaryotes

3.1. Feeding/Nutrient Acquisition

3.2. Pathogenicity

3.3. Self-Nonself Discrimination

3.4. Intercellular Communication

4. Trogocytosis in Parasitic Protists

4.1. Trichomonas Vaginalis

4.2. Giardia Intestinalis

4.3. Trypanosoma and Leishmania

4.4. Plasmodium

4.5. Toxoplasma Gondii

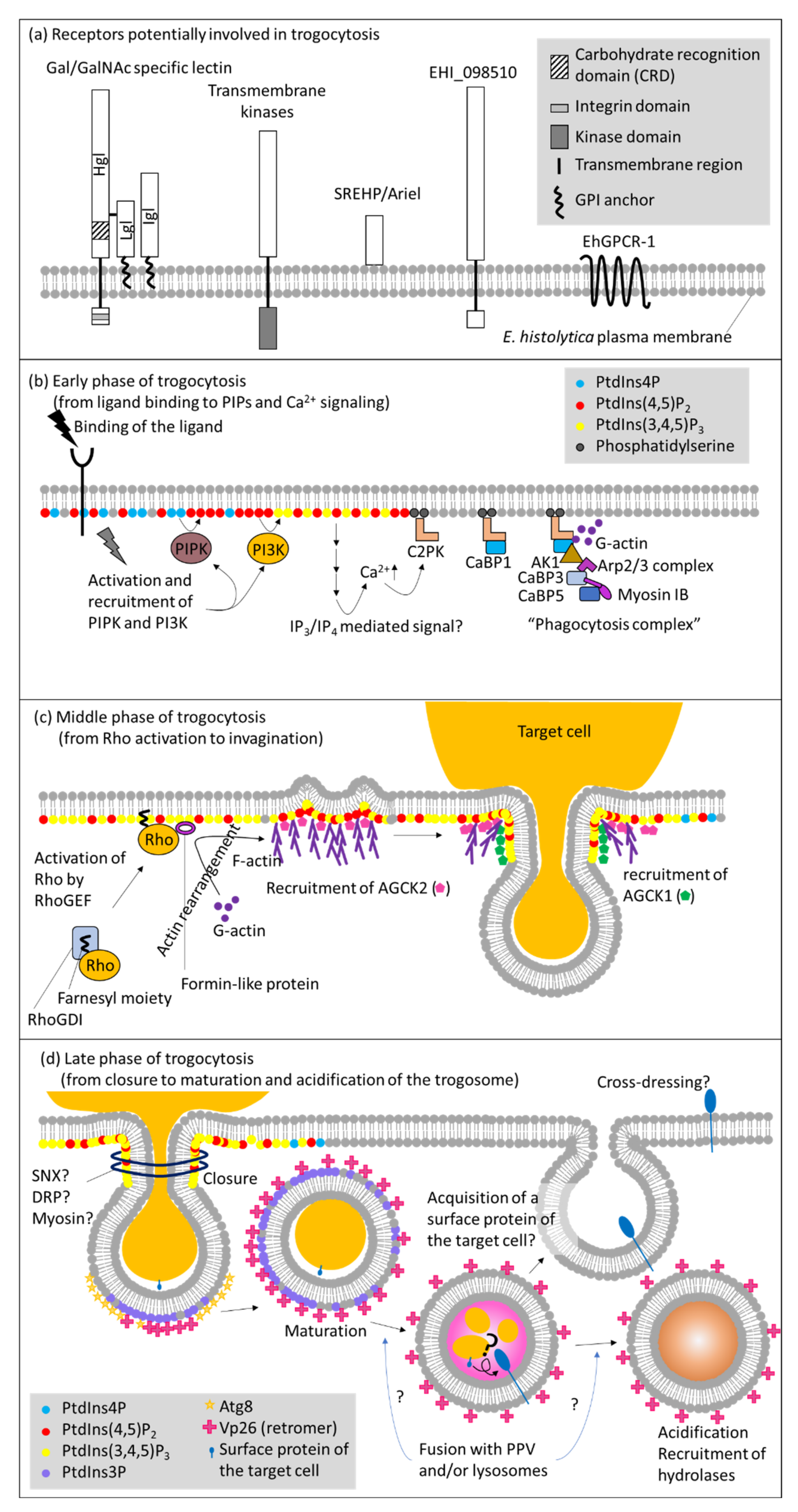

5. Molecular Mechanisms of Trogocytosis in E. histolytica

5.1. Receptors and Downstream Signaling

5.2. Phosphatidylinositol, Calcium Signaling, and Protein Kinases

5.3. Cytoskeletal Reorganization via Rho Small GTPases

5.4. Closure of Trogosomes

5.5. Maturation of Trogosomes vs. Phagosomes

5.6. Physiological Role of Trogocytosis in E. histolytica

6. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Cavalier-Smith, T. The Phagotrophic Origin of Eukaryotes and Phylogenetic Classification of Protozoa. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 297–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalier-Smith, T. Predation and Eukaryote Cell Origins: A Coevolutionary Perspective. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 41, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mast, S.O.; Root, F.M. Observations on Ameba Feeding on Infusoria, and Their Bearing on the Surface-Tension Theory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1916, 2, 188–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beers, C.D. Observations on Amoeba Feeding on the Ciliate Frontonia. J. Exp. Biol. 1924, 1, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, K.W.; Jeon, M.S. Generation of Mechanical Forces in Phagocytosing Amoebae: Light and Electron Microscopic Study 1. J. Protozool. 1983, 30, 536–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, D.R. A Predatory Slime Mould. Nature 1982, 298, 464–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, D.R.; Vogel, G. Phagocytic Behavior of the Predatory Slime Mold, Dictyostelium caveatum. Exp. Cell Res. 1985, 159, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culbertson, C.G. Pathogenic Naegleria and Hartmannella (Acanthamoeba). Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1970, 174, 1018–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culbertson, C.G. The Pathogenicity of Soil Amebas. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1971, 25, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. Observations by Immunofluorescence Microscopy and Electron Microscopy on the Cytopathogenicity of Naegleria fowleri in Mouse Embryo-Cell Cultures. J. Med. Microbiol. 1979, 12, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Councilman, W.T.; LaFleur, H.A. Amoebic Dysentery. Johns Hopkins Hosp. Rep. 1891, 2, 395. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco, E.; Guarneros, G.; Martinez-Palomo, A.; Sánchez, T. Entamoeba histolytica. Phagocytosis as a Virulence Factor. J. Exp. Med. 1983, 158, 1511–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Palomo, A.; Gonzalez-Robles, A.; Chavez, B.; Orozco, E.; Fernandez-Castelo, S.; Cervantes, A. Structural Bases of the Cytolytic Mechanisms of Entamoeba histolytica. J. Protozool. 1985, 32, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Palomo, A.; da Silva, P.P.; Chavez, B. Membrane Structure of Entamoeba histolytica: Fine Structure of Freeze-Fractured Membranes. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1976, 54, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejeune, A.; Gicquaud, C. Evidence for Two Mechanisms of Human Erythrocyte Endocytosis by Entamoeba histolytica-like Amoebae (Laredo Strain). Biol. Cell 1987, 59, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ralston, K.S.; Solga, M.D.; Mackey-Lawrence, N.M.; Somlata, N.; Bhattacharya, A.; Petri, W.A. Trogocytosis by Entamoeba histolytica Contributes to Cell Killing and Tissue Invasion. Nature 2014, 508, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, H.W.; Suleiman, R.L.; Ralston, K.S. Trogocytosis by Entamoeba histolytica Mediates Acquisition and Display of Human Cell Membrane Proteins and Evasion of Lysis by Human Serum. mBio 2019, 10, e00068-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibáñez-Escribano, A.; Nogal-Ruiz, J.J.; Pérez-Serrano, J.; Gómez-Barrio, A.; Escario, J.A.; Alderete, J.F. Sequestration of Host-CD59 as Potential Immune Evasion Strategy of Trichomonas vaginalis. Acta Trop. 2015, 149, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Chen, J.; Zhong, X.; Liang, P.; Lin, W. Ultrastructural and Immunohistochemical Studies on Trichomonas vaginalis Adhering to and Phagocytizing Genitourinary Epithelial Cells. Chin. Med. J. Engl. 2004, 117, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aikawa, M.; Hepler, P.K.; Huff, C.G.; Sprinz, H. The Feeding Mechanism of Avian Malarial Parasites. J. Cell Biol. 1966, 28, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudzinska, M.A.; Trager, W.; Bray, R.S. Pinocytotic Uptake and the Digestion of Hemoglobin in Malaria Parasites. J. Protozool. 1965, 12, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado, L.M.; Nadovich, C.T.; Spadafora, C. Malarial Hemozoin: From Target to Tool. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1840, 2032–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, M.D.; Schneider, T.G.; Taraschi, T.T.T.F. A New Model for Hemoglobin Ingestion and Transport by the Human Malaria Parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 1937–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, B.A.; Chiappino, M.L.; Pavesio, C.E. Endocytosis at the Micropore of Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitol. Res. 1994, 80, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, B.N.; Yasuda, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Saito-Nakano, Y.; Nozaki, T. Differences in Morphology of Phagosomes and Kinetics of Acidification and Degradation in Phagosomes between the Pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica and the Non-Pathogenic Entamoeba dispar. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 2005, 62, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito-Nakano, Y.; Yasuda, T.; Nakada-Tsukui, K.; Leippe, M.; Nozaki, T. Rab5-Associated Vacuoles Play a Unique Role in Phagocytosis of the Enteric Protozoan Parasite Entamoeba histolytica. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 49497–49507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, B.N.; Kobayashi, S.; Saito-Nakano, Y.; Nozaki, T. Entamoeba histolytica: Differences in Phagosome Acidification and Degradation between Attenuated and Virulent Strains. Exp. Parasitol. 2006, 114, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picazarri, K.; Nakada-Tsukui, K.; Tsuboi, K.; Miyamoto, E.; Watanabe, N.; Kawakami, E.; Nozaki, T. Atg8 Is Involved in Endosomal and Phagosomal Acidification in the Parasitic Protist Entamoeba histolytica. Cell Microbiol. 2015, 17, 1510–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, N.; Nakada-Tsukui, K.; Nozaki, T. Two Isotypes of Phosphatidylinositol 3-Phosphate-Binding Sorting Nexins Play Distinct Roles in Trogocytosis in Entamoeba histolytica. Cell Microbiol. 2020, 22, e13144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campillo, C.; Jerber, J.; Fisch, C.; Simoes-Betbeder, M.; Dupuis-Williams, P.; Nassoy, P.; Sykes, C. Mechanics of Membrane–Cytoskeleton Attachment In Paramecium. New, J. Phys. 2012, 14, 125016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomel, S.; Diogon, M.; Bouchard, P.; Pradel, L.; Ravet, V.; Coffe, G.; Viguès, B. The Membrane Skeleton in Paramecium: Molecular Characterization of a Novel Epiplasmin Family and Preliminary GFP Expression Results. Protist 2006, 157, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kissmehl, R.; Sehring, I.M.; Wagner, E.; Plattner, H. Immunolocalization of Actin in Paramecium Cells. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2004, 52, 1543–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorselen, D.; Labitigan, R.L.D.; Theriot, J.A. A Mechanical Perspective on Phagocytic Cup Formation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2020, 66, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmartin, A.A.; Ralston, K.S.; Petri, W.A. Inhibition of Amebic Cysteine Proteases Blocks Amebic Trogocytosis but Not Phagocytosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 221, 1734–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercer, F.; Ng, S.H.; Brown, T.M.; Boatman, G.; Johnson, P.J. Neutrophils Kill the Parasite Trichomonas vaginalis Using Trogocytosis. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2003885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S.J. Tissue Destruction by Neutrophils. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989, 320, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taggart, C.C.; Greene, C.M.; Carroll, T.P.; O’Neill, S.J.; McElvaney, N.G. Elastolytic Proteases: Inflammation Resolution and Dysregulation in Chronic Infective Lung Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 171, 1070–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Lessieur, E.M.; Saadane, A.; Lindstrom, S.I.; Taylor, P.R.; Kern, T.S. Neutrophil Elastase Contributes to the Pathological Vascular Permeability Characteristic of Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 2365–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellberg, A.; Nickel, R.; Lotter, H.; Tannich, E.; Bruchhaus, I. Overexpression of Cysteine Proteinase 2 in Entamoeba histolytica or Entamoeba dispar Increases Amoeba-Induced Monolayer Destruction in Vitro but Does Not Augment Amoebic Liver Abscess Formation in Gerbils. Cell Microbiol. 2001, 3, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thibeaux, R.; Dufour, A.; Roux, P.; Bernier, M.; Baglin, A.-C.; Frileux, P.; Olivo-Marin, J.C.; Guillén, N.; Labruyère, E. Newly Visualized Fibrillar Collagen Scaffolds Dictate Entamoeba histolytica Invasion Route in the Human Colon. Cell Microbiol. 2012, 14, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thibeaux, R.; Avé, P.; Bernier, M.; Morcelet, M.; Frileux, P.; Guillén, N.; Labruyère, E. The Parasite Entamoeba histolytica Exploits the Activities of Human Matrix Metalloproteinases to Invade Colonic Tissue. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M.; McKerrow, J.H. Cysteine Proteases of Parasitic Organisms. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2002, 120, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, H.J.; Babbitt, P.C.; Sajid, M. The Global Cysteine Peptidase Landscape in Parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2009, 25, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronado-Velázquez, D.; Betanzos, A.; Serrano-Luna, J.; Shibayama, M. An In Vitro Model of the Blood-Brain Barrier: Naegleria fowleri Affects the Tight Junction Proteins and Activates the Microvascular Endothelial Cells. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2018, 65, 804–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Kang, J.-M.; Joo, S.-Y.; Song, S.-M.; Lê, H.G.; Thái, T.L.; Lee, J.-Y.; Goo, Y.-K.; Chung, D.-I.; Sohn, W.-M.; et al. Molecular and Biochemical Properties of a Cysteine Protease of Acanthamoeba castellanii. Korean J. Parasitol. 2018, 56, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa, A.; Paz-y-Miño-C, G. Discrimination Experiments in Entamoeba and Evidence from Other Protists Suggest Pathogenic Amebas Cooperate with Kin to Colonize Hosts and Deter Rivals. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2019, 66, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, E.L. From Darwin and Metchnikoff to Burnet and Beyond. Trends Innate Immun. 2008, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzik, J.M. The Ancestry and Cumulative Evolution of Immune Reactions. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2010, 57, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.C.; Kusch, J. Communicative Functions of GPI-Anchored Surface Proteins in Unicellular Eukaryotes. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 39, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, D.R.; Duffy, K.T. Breakdown of Self/Nonself Recognition in Cannibalistic Strains of the Predatory Slime Mold, Dictyostelium caveatum. J. Cell Biol. 1986, 102, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benabentos, R.; Hirose, S.; Sucgang, R.; Curk, T.; Katoh, M.; Ostrowski, E.A.; Strassmann, J.E.; Queller, D.C.; Zupan, B.; Shaulsky, G.; et al. Polymorphic Members of the Lag Gene Family Mediate Kin Discrimination in Dictyostelium. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, S.; Benabentos, R.; Ho, H.-I.; Kuspa, A.; Shaulsky, G. Self-Recognition in Social Amoebae Is Mediated by Allelic Pairs of Tiger Genes. Science 2011, 333, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirose, S.; Chen, G.; Kuspa, A.; Shaulsky, G. The Polymorphic Proteins TgrB1 and TgrC1 Function as a Ligand-Receptor Pair in Dictyostelium Allorecognition. J. Cell Sci. 2017, 208, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, I.S.; Inouye, K. Species Recognition in Social Amoebae. J. Biosci. 2018, 43, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa, A.; Paz-Y-Miño-C, G.; Hackey, M.; Rutherford, S. Entamoeba Clone-Recognition Experiments: Morphometrics, Aggregative Behavior, and Cell-Signaling Characterization. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2016, 63, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, M.; Takeda, K.; Kawano, M.; Takai, T.; Ishii, N.; Ogasawara, K. Natural Killer (NK)-Dendritic Cell Interactions Generate MHC Class II-Dressed NK Cells That Regulate CD4+ T Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 18360–18365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Nakayama, M.; Kawano, M.; Amagai, R.; Ishii, T.; Harigae, H.; Ogasawara, K. Fratricide of Natural Killer Cells Dressed with Tumor-Derived NKG2D Ligand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 9421–9426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, K.; Shiozawa, N.; Nagao, T.; Yoshikawa, S.; Yamanishi, Y.; Karasuyama, H. Trogocytosis of Peptide-MHC Class II Complexes from Dendritic Cells Confers Antigen-Presenting Ability on Basophils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 1111–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamieh, M.; Dobrin, A.; Cabriolu, A.; van der Stegen, S.J.C.; Giavridis, T.; Mansilla-Soto, J.; Eyquem, J.; Zhao, Z.; Whitlock, B.M.; Miele, M.M.; et al. CAR T Cell Trogocytosis and Cooperative Killing Regulate Tumour Antigen Escape. Nature 2019, 568, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Sun, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhan, B.; Zhu, X. Complement Evasion: An Effective Strategy That Parasites Utilize to Survive in the Host. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooyman, D.; Byrne, G.; McClellan, S.; Nielsen, D.; Tone, M.; Waldmann, H.; Coffman, T.; McCurry, K.; Platt, J.; Logan, J. In Vivo Transfer of GPI-Linked Complement Restriction Factors from Erythrocytes to the Endothelium. Science 1995, 269, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, A.; Harris, C.L.; Court, J.; Mason, M.D.; Morgan, B.P. Antigen-Presenting Cell Exosomes Are Protected from Complement-Mediated Lysis by Expression of CD55 and CD59. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003, 33, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, G.A. The Release of Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchored Proteins from the Cell Surface. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2018, 656, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dance, A. Core Concept: Cells Nibble One Another via the under-Appreciated Process of Trogocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 17608–17610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissinger, P. Trichomonas vaginalis: A Review of Epidemiologic, Clinical and Treatment Issues. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midlej, V.; Benchimol, M. Trichomonas vaginalis Kills and Eats--Evidence for Phagocytic Activity as a Cytopathic Effect. Parasitology 2010, 137, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercer, F.; Johnson, P.J. Trichomonas vaginalis: Pathogenesis, Symbiont Interactions, and Host Cell Immune Responses. Trends Parasitol. 2018, 34, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira-Neves, A.; Benchimol, M. Phagocytosis by Trichomonas vaginalis: New Insights. Biol. Cell 2007, 99, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caterina, P.; Lynch, D.; Ashman, R.B.; Warton, A.; Papadimitriou, J.M. Complement-Mediated Regulation of Trichomonas vaginalis Infection in Mice. Exp. Clin. Immunogenet. 1999, 16, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livson, S.; Jarva, H.; Kalliala, I.; Lokki, A.I.; Heikkinen-Eloranta, J.; Nieminen, P.; Meri, S. Activation of the Complement System in the Lower Genital Tract During Pregnancy and Delivery. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 563073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchimol, M. Giardia intestinalis Can Interact, Change Its Shape and Internalize Large Particles and Microorganisms. Parasitology 2021, 148, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abodeely, M.; DuBois, K.N.; Hehl, A.; Stefanic, S.; Sajid, M.; DeSouza, W.; Attias, M.; Engel, J.C.; Hsieh, I.; Fetter, R.D.; et al. A Contiguous Compartment Functions as Endoplasmic Reticulum and Endosome/Lysosome in Giardia lamblia. Eukaryot. Cell 2009, 8, 1665–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faubert, G. Immune Response to Giardia duodenalis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans-Osses, I.; Ansa-Addo, E.A.; Inal, J.M.; Ramirez, M.I. Involvement of Lectin Pathway Activation in the Complement Killing of Giardia intestinalis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 395, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijo-Ferreira, F.; Takahashi, J.S. Sleeping Sickness: A Tale of Two Clocks. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 525097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messenger, L.A.; Miles, M.A.; Bern, C. Between a Bug and a Hard Place: Trypanosoma cruzi Genetic Diversity and the Clinical Outcomes of Chagas Disease. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2015, 13, 995–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gramiccia, M.; Gradoni, L. The Current Status of Zoonotic Leishmaniases and Approaches to Disease Control. Int. J. Parasitol. 2005, 35, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reithinger, R.; Dujardin, J.-C.; Louzir, H.; Pirmez, C.; Alexander, B.; Brooker, S. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2007, 7, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Guerrero, E.; Quintanilla-Cedillo, M.R.; Ruiz-Esmenjaud, J.; Arenas, R. Leishmaniasis: A Review. Research 2017, 6, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, H.; de Souza, W. On the Fine Structure of Trypanosoma cruzi in Tissue Cultures of Pigment Epithelium from the Chick Embryo. Uptake of Melanin Granules by the Parasite. J. Protozool. 1973, 20, 590–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, P.F.; de Souza, W.; Souto-Padrón, T.; da Silva, P.P. The Cell Surface of Trypanosoma cruzi: A Fracture-Flip, Replica-Staining Label-Fracture Survey. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1989, 50, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vidal, J.C.; Alcantara, C.d.L.; de Souza, W.; Cunha-e-Silva, N.L. Loss of the Cytostome-Cytopharynx and Endocytic Ability Are Late Events in Trypanosoma cruzi Metacyclogenesis. J. Struct. Biol. 2016, 196, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinert, M.; Novikoff, A.B. The Existence of a Cytostome and the Occurrence of Pinocytosis in the Trypanosome, Trypanosoma mega. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 1960, 8, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, T.M. The Form and Function of the Cytostome-Cytopharynx of the Culture Forms of the Elasmobranch Haemoflagellate Trypanosoma raiae Laveran & Mesnil. J. Protozool. 1969, 16, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milder, R.; Deane, M.P. The Cytostome of Trypanosoma cruzi and T. conorhini. J. Protozool. 1969, 16, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinman, D.; White, E.A.; Antipa, G.A. Trypanosoma lucknowi, a New Species of Trypanosome from Macaca mulatta with Observations on Its Fine Structure. J. Protozool. 1984, 31, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliday, C.; Billington, K.; Wang, Z.; Madden, R.; Dean, S.; Sunter, J.D.; Wheeler, R.J. Cellular Landmarks of Trypanosoma brucei and Leishmania mexicana. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2019, 230, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliday, C.; de Castro-Neto, A.; Alcantara, C.L.; Cunha-E.-Silva, N.L.; Vaughan, S.; Sunter, J.D. Trypanosomatid Flagellar Pocket from Structure to Function. Trends Parasitol. 2021, 37, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowman, A.F.; Healer, J.; Marapana, D.; Marsh, K. Malaria: Biology and Disease. Cell 2016, 167, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langreth, S.G.; Jensen, J.B.; Reese, R.T.; Trager, W. Fine Structure of Human Malaria in Vitro. J. Protozool. 1978, 25, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olliaro, P.; Castelli, F.; Milano, F.; Filice, G.; Carosi, G. Ultrastructure of Plasmodium falciparum “in Vitro”. I. Base-Line for Drug Effects Evaluation. Microbiologica 1989, 12, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bakar, N.A.; Klonis, N.; Hanssen, E.; Chan, C.; Tilley, L. Digestive-Vacuole Genesis and Endocytic Processes in the Early Intraerythrocytic Stages of Plasmodium falciparum. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, M.T.; Vaid, A.; Hosgood, H.D.; Vijay, J.; Bhattacharya, A.; Sahani, M.H.; Baevova, P.; Joiner, K.A.; Sharma, P. Traffic to the Malaria Parasite Food Vacuole. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 11499–11508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, D.A.; McIntosh, M.T.; Hosgood, H.D.; Chen, S.; Zhang, G.; Baevova, P.; Joiner, K.A. Four Distinct Pathways of Hemoglobin Uptake in the Malaria Parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2463–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, S.; Klemba, M. Amino Acid Efflux by Asexual Blood-Stage Plasmodium falciparum and Its Utility in Interrogating the Kinetics of Hemoglobin Endocytosis and Catabolism in Vivo. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2015, 201, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhakar, R.; Das, D.; Thanumalayan, S.; Gorde, S.; Sijwali, P.S. Plasmodium falciparum Atg18 Localizes to the Food Vacuole via Interaction with the Multi-Drug Resistance Protein 1 and Phosphatidylinositol 3-Phosphate. Biochem. J. 2021, 478, 1705–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya, J.G.; Liesenfeld, O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 2004, 363, 1965–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfert, E.A.; Blader, I.J.; Wilson, E.H. Brains and Brawn: Toxoplasma Infections of the Central Nervous System and Skeletal Muscle. Trends Parasitol. 2017, 33, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, Z.; McGovern, O.L.; Di Cristina, M.; Carruthers, V.B. Toxoplasma gondii Ingests and Digests Host Cytosolic Proteins. mBio 2014, 5, e01188-01114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannan, G.; Thaprawat, P.; Schultz, T.L.; Carruthers, V.B. Acquisition of Host Cytosolic Protein by Toxoplasma gondii Bradyzoites. mSphere 2021, 6, e00934-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGovern, O.L.; Rivera-Cuevas, Y.; Carruthers, V.B. Emerging Mechanisms of Endocytosis in Toxoplasma gondii. Life 2021, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, J.D.; Sonda, S.; Bergbower, E.; Smith, M.E.; Coppens, I. Toxoplasma gondii Salvages Sphingolipids from the Host Golgi through the Rerouting of Selected Rab Vesicles to the Parasitophorous Vacuole. Mol. Biol. Cell 2013, 24, 1974–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppens, I.; Dunn, J.D.; Romano, J.D.; Pypaert, M.; Zhang, H.; Boothroyd, J.C.; Joiner, K.A. Toxoplasma gondii Sequesters Lysosomes from Mammalian Hosts in the Vacuolar Space. Cell 2006, 125, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, J.D.; Nolan, S.J.; Porter, C.; Ehrenman, K.; Hartman, E.J.; Hsia, R.-C.; Coppens, I. The Parasite Toxoplasma Sequesters Diverse Rab Host Vesicles within an Intravacuolar Network. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 216, 4235–4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somlata, N.; Nakada-Tsukui, K.; Nozaki, T. AGC Family Kinase 1 Participates in Trogocytosis but Not in Phagocytosis in Entamoeba histolytica. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito-Nakano, Y.; Wahyuni, R.; Nakada-Tsukui, K.; Tomii, K.; Nozaki, T. Rab7D Small GTPase Is Involved in Phago-, Trogocytosis and Cytoskeletal Reorganization in the Enteric Protozoan Entamoeba histolytica. Cell Microbiol. 2021, 23, e13267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettadapur, A.; Miller, H.W.; Ralston, K.S. Biting Off What Can Be Chewed: Trogocytosis in Health, Infection, and Disease. Infect. Immun. 2020, 88, e00930-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe-Querol, E.; Rosales, C. Phagocytosis: Our Current Understanding of a Universal Biological Process. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.L.; Harrison, R.E. Microbial Phagocytic Receptors and Their Potential Involvement in Cytokine Induction in Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 662063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penberthy, K.K.; Ravichandran, K.S. Apoptotic Cell Recognition Receptors and Scavenger Receptors. Immunol. Rev. 2016, 269, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada-Tsukui, K.; Nozaki, T. Receptors for Phagocytosis and Trogocytosis in Entamoeba histolytica. In Eukaryome Impact on Human Intestine Homeostasis and Mucosal Immunology Overview of the First Eukaryome Congress at Insitut Pasteur Proceedings of the Overview of the First Eukaryome Congress at Insitut Pasteur, Paris, France, 16–18 October 2019, 1st ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-44825-7. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, M.T.; Agbedanu, P.N.; Zamanian, M.; Day, T.A.; Carlson, S.A. Evidence for a Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide-Recognizing G-Protein-Coupled Receptor in the Bacterial Engulfment by Entamoeba histolytica. Eukaryot. Cell 2013, 12, 1433–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ravdin, J.I.; Guerrant, R.L. Role of Adherence in Cytopathogenic Mechanisms of Entamoeba histolytica. Study with Mammalian Tissue Culture Cells and Human Erythrocytes. J. Clin. Investig. 1981, 68, 1305–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracha, R.; Mirelman, D. Adherence and Ingestion of Escherichia coli Serotype 055 by Trophozoites of Entamoeba histolytica. Infect. Immun. 1983, 40, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petri, W.A.; Smith, R.D.; Schlesinger, P.H.; Murphy, C.F.; Ravdin, J.I. Isolation of the Galactose-Binding Lectin That Mediates the in Vitro Adherence of Entamoeba histolytica. J. Clin. Investig. 1987, 80, 1238–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petri, W.A.; Ravdin, J.I. Cytopathogenicity of Entamoeba histolytica: The Role of Amebic Adherence and Contact-Dependent Cytolysis in Pathogenesis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1987, 3, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadee, K.; Petri, W.A.; Innes, D.J.; Ravdin, J.I. Rat and Human Colonic Mucins Bind to and Inhibit Adherence Lectin of Entamoeba histolytica. J. Clin. Investig. 1987, 80, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huston, C.D.; Boettner, D.R.; Miller-Sims, V.; Petri, W.A. Apoptotic Killing and Phagocytosis of Host Cells by the Parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 964–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadee, K.; Johnson, M.L.; Orozco, E.; Petri, W.A.; Ravdin, J.I. Binding and Internalization of Rat Colonic Mucins by the Galactose/N-Acetyl-n-Galactosamine Adherence Lectin of Entamoeba histolytica. J. Infect. Dis. 1988, 158, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vines, R.R.; Ramakrishnan, G.; Rogers, J.B.; Lockhart, L.A.; Mann, B.J.; Petri, W.A. Regulation of Adherence and Virulence by the Entamoeba histolytica Lectin Cytoplasmic Domain, Which Contains a Beta2 Integrin Motif. Mol. Biol. Cell 1998, 9, 2069–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, B.J. Structure and Function of the Entamoeba histolytica Gal/GalNAc Lectin. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2002, 216, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, M.A.; Lee, C.W.; Holm, C.F.; Ghosh, S.; Mills, A.; Lockhart, L.A.; Reed, S.L.; Mann, B.J. Identification of Entamoeba histolytica Thiol-Specific Antioxidant as a GalNAc Lectin-Associated Protein. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2003, 127, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, J.J.; Mann, B.J. Proteomic Analysis of Gal/GalNAc Lectin-Associated Proteins in Entamoeba histolytica. Exp. Parasitol. 2005, 110, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somlata, N.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhattacharya, A. A C2 Domain Protein Kinase Initiates Phagocytosis in the Protozoan Parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada-Tsukui, K.; Watanabe, N.; Maehama, T.; Nozaki, T. Phosphatidylinositol Kinases and Phosphatases in Entamoeba histolytica. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babuta, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhattacharya, A. Entamoeba histolytica and Pathogenesis: A Calcium Connection. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Samuelson, J. Involvement of P21racA, Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase, and Vacuolar ATPase in Phagocytosis of Bacteria and Erythrocytes by Entamoeba histolytica: Suggestive Evidence for Coincidental Evolution of Amebic Invasiveness. Infect. Immun. 1997, 65, 4243–4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raha, S.; Dalal, B.; Biswas, S.; Biswas, B.B. Myo-Inositol Trisphosphate-Mediated Calcium Release from Internal Stores of Entamoeba histolytica. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1994, 65, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, B.; Raha, S.; Bhattacharyya, B.; Biswas, S.; Biswas, B.B. Relative Importance of Inositol (1,4,5)Trisphosphate and Inositol (1,3,4,5)Tetrakisphosphate in Entamoeba histolytica. FEBS Lett. 1996, 393, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijken, P.; de Haas, J.R.; Craxton, A.; Erneux, C.; Shears, S.B.; Van Haastert, P.J. A Novel, Phospholipase C-Independent Pathway of Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate Formation in Dictyostelium and Rat Liver. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 29724–29731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prole, D.L.; Taylor, C.W. Identification of Intracellular and Plasma Membrane Calcium Channel Homologues in Pathogenic Parasites. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, M.; Enomoto, M.; Morales, J.; Kurebayashi, N.; Sakurai, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Nara, T.; Mikoshiba, K. Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate Receptor Regulates Replication, Differentiation, Infectivity and Virulence of the Parasitic Protist Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Microbiol. 2013, 87, 1133–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijken, P.V.; Bergsma, J.C.T.; Haastert, P.J.M.V. Phospholipase-C-Independent Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate Formation in Dictyostelium Cells—Activation of a Plasma-Membrane-Bound Phosphatase by Receptor-Stimulated Ca2+ Influx. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997, 244, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansuri, M.S.; Babuta, M.; Ali, M.S.; Bharadwaj, R.; Deep, J.G.; Gourinath, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhattacharya, A. Autophosphorylation at Thr279 of Entamoeba histolytica Atypical Kinase EhAK1 Is Required for Activity and Regulation of Erythrophagocytosis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 16969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somlata, J.; Bhradwaj, R.; Nozaki, T. PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 Binding Protein Screening Reveals Unique Molecules Involved in Endocytic Processes, 1st ed.; Guillen, N., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-44825-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, L.R.; Komander, D.; Alessi, D.R. The Nuts and Bolts of AGC Protein Kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anamika, K.; Bhattacharya, A.; Srinivasan, N. Analysis of the Protein Kinome of Entamoeba histolytica. Proteins 2008, 71, 995–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano-Sugaya, T.; Izumiyama, S.; Yanagawa, Y.; Saito-Nakano, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Kobayashi, S.; Nakada-Tsukui, K.; Nozaki, T. Near-Chromosome Level Genome Assembly Reveals Ploidy Diversity and Plasticity in the Intestinal Protozoan Parasite Entamoeba histolytica. BMC Gennomics 2020, 21, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A.B.; Hall, A. Rho Gtpases: Biochemistry and Biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005, 21, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rottner, K.; Stradal, T.E. Actin Dynamics and Turnover in Cell Motility. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2011, 23, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlach, B.D.; Marinello, M.; Heinz, J.; Rymut, N.; Sansbury, B.E.; Riley, C.O.; Sadhu, S.; Hosseini, Z.; Kojima, Y.; Tang, D.D.; et al. Resolvin D1 Promotes the Targeting and Clearance of Necroptotic Cells. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén, N.; Boquet, P.; Sansonetti, P. The Small GTP-Binding Protein RacG Regulates Uroid Formation in the Protozoan Parasite Entamoeba histolytica. J. Cell Sci. 1998, 111 Pt. 12, 1729–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, R.; Arya, R.; Shahid, M.M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhattacharya, A. EhRho1 Regulates Plasma Membrane Blebbing through PI3 Kinase in Entamoeba histolytica. Cell Microbiol. 2017, 19, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharadwaj, R.; Sharma, S.; Janhawi, J.; Arya, R.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhattacharya, A. EhRho1 Regulates Phagocytosis by Modulating Actin Dynamics through EhFormin1 and EhProfilin1 in Entamoeba histolytica. Cell Microbiol. 2018, 20, e12851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdu, Y.; Maniscalco, C.; Heddleston, J.M.; Chew, T.-L.; Nance, J. Developmentally Programmed Germ Cell Remodelling by Endodermal Cell Cannibalism. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makiuchi, T.; Santos, H.J.; Tachibana, H.; Nozaki, T. Hetero-Oligomer of Dynamin-Related Proteins Participates in the Fission of Highly Divergent Mitochondria from Entamoeba histolytica. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, J.A.; Johnson, M.T.; Beningo, K.; Post, P.; Mooseker, M.; Araki, N. A Contractile Activity That Closes Phagosomes in Macrophages. J. Cell Sci. 1999, 112(Pt. 3), 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhattacharya, A. The Calmodulin-like Calcium Binding Protein EhCaBP3 of Entamoeba histolytica Regulates Phagocytosis and Is Involved in Actin Dynamics. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1003055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada-Tsukui, K.; Saito-Nakano, Y.; Ali, V.; Nozaki, T. A Retromerlike Complex Is a Novel Rab7 Effector That Is Involved in the Transport of the Virulence Factor Cysteine Protease in the Enteric Protozoan Parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Mol. Biol. Cell 2005, 16, 5294–5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakada-Tsukui, K.; Okada, H.; Mitra, B.N.; Nozaki, T. Phosphatidylinositol-Phosphates Mediate Cytoskeletal Reorganization during Phagocytosis via a Unique Modular Protein Consisting of RhoGEF/DH and FYVE Domains in the Parasitic Protozoon Entamoeba histolytica. Cell Microbiol. 2009, 11, 1471–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, A.; Nakada-Tsukui, K.; Nozaki, T. Novel Transmembrane Receptor Involved in Phagosome Transport of Lysozymes and β-Hexosaminidase in the Enteric Protozoan Entamoeba histolytica. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nakada-Tsukui, K.; Tsuboi, K.; Furukawa, A.; Yamada, Y.; Nozaki, T. A Novel Class of Cysteine Protease Receptors That Mediate Lysosomal Transport. Cell Microbiol. 2012, 14, 1299–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, A.; Nakada-Tsukui, K.; Nozaki, T. Cysteine Protease-Binding Protein Family 6 Mediates the Trafficking of Amylases to Phagosomes in the Enteric Protozoan Entamoeba histolytica. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 1820–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marumo, K.; Nakada-Tsukui, K.; Tomii, K.; Nozaki, T. Ligand Heterogeneity of the Cysteine Protease Binding Protein Family in the Parasitic Protist Entamoeba histolytica. Int. J. Parasitol. 2014, 44, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yutin, N.; Wolf, M.Y.; Wolf, Y.I.; Koonin, E.V. The Origins of Phagocytosis and Eukaryogenesis. Biol. Direct 2009, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trogocyte | Life Style | Life Cycle | Trogocytosis Target | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoeba proteus | free-living | trophozoite | ciliate (Paramecium, Frontonia) | [3,4] |

| Chaos carolinensis | free-living | trophozoite | ciliate (Blapharisma) | [5] |

| Dictyostelium caveatum | free-living | trophozoite | other Dictyosterium (D. discoideum) | [6,7] |

| Naegleria fowleri | free-living/parasititc (extracellular) | trophozoite | mammalian cell | [8,9,10] |

| Hartmannella-Acanthamoeba | free-living/parasititc (extracellular) | trophozoite | mammalian cell | [8,9] |

| Entamoeba histolytica | extracellular parasite (intestine) | trophozoite | mammalian cell | [16,17] |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | extracellular parasite (urogenital tract) | trophozoite | mammalian cell | [18,19] |

| Plasmodium falciparum | intracellular parasite (erythrocyte) | erythrocytic (trophozoite) | parasitizing erythrocyte | [20,21,22,23] |

| Toxoplasma gondii | intracellular parasite (nucleated cells) | tachyzoites; bradizoites | parasitizing mammalian cell | [24] |

| Category | Molecules | Trogocytosis | Phagocytosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adherence | Surface Molecules | Gal lectin | Gal lectin Transmembranare kinases SREHP/Ariel EHI_098510 EhGPCR-1 |

| Signaling | Phosphatidylinositol kinases | PI3K | PIPKI PI3K |

| Protein kinases | C2PK AGCK1 AGCK2 | C2PK AGCK2 AK1 | |

| Calcium binding proteins | Unknown | CaBP1/3/5 | |

| Formation | Cytoskeletal proteins and regulators | actin | Actin Formin Arp2/3 complex EhRho1 EhRacA |

| Closure | Cytoskeletal proteins and regulators | Unknown | Myosin IB |

| Maturation | Phospholipids, vesicular traffic-related proteins | PtdIns3P Vps26 (retromer) Atg8 | PtdIns3P Vps26 (retromer) Atg8 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nakada-Tsukui, K.; Nozaki, T. Trogocytosis in Unicellular Eukaryotes. Cells 2021, 10, 2975. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10112975

Nakada-Tsukui K, Nozaki T. Trogocytosis in Unicellular Eukaryotes. Cells. 2021; 10(11):2975. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10112975

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakada-Tsukui, Kumiko, and Tomoyoshi Nozaki. 2021. "Trogocytosis in Unicellular Eukaryotes" Cells 10, no. 11: 2975. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10112975

APA StyleNakada-Tsukui, K., & Nozaki, T. (2021). Trogocytosis in Unicellular Eukaryotes. Cells, 10(11), 2975. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10112975