Mitochondrial Disruption by Amyloid Beta 42 Identified by Proteomics and Pathway Mapping

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Treatment

2.2. Liquid-Chromatography Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry

2.3. Protein Identification and Quantification

2.4. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) and Genomic Enrichment Analysis (GEA)

2.5. Statistics

3. Results

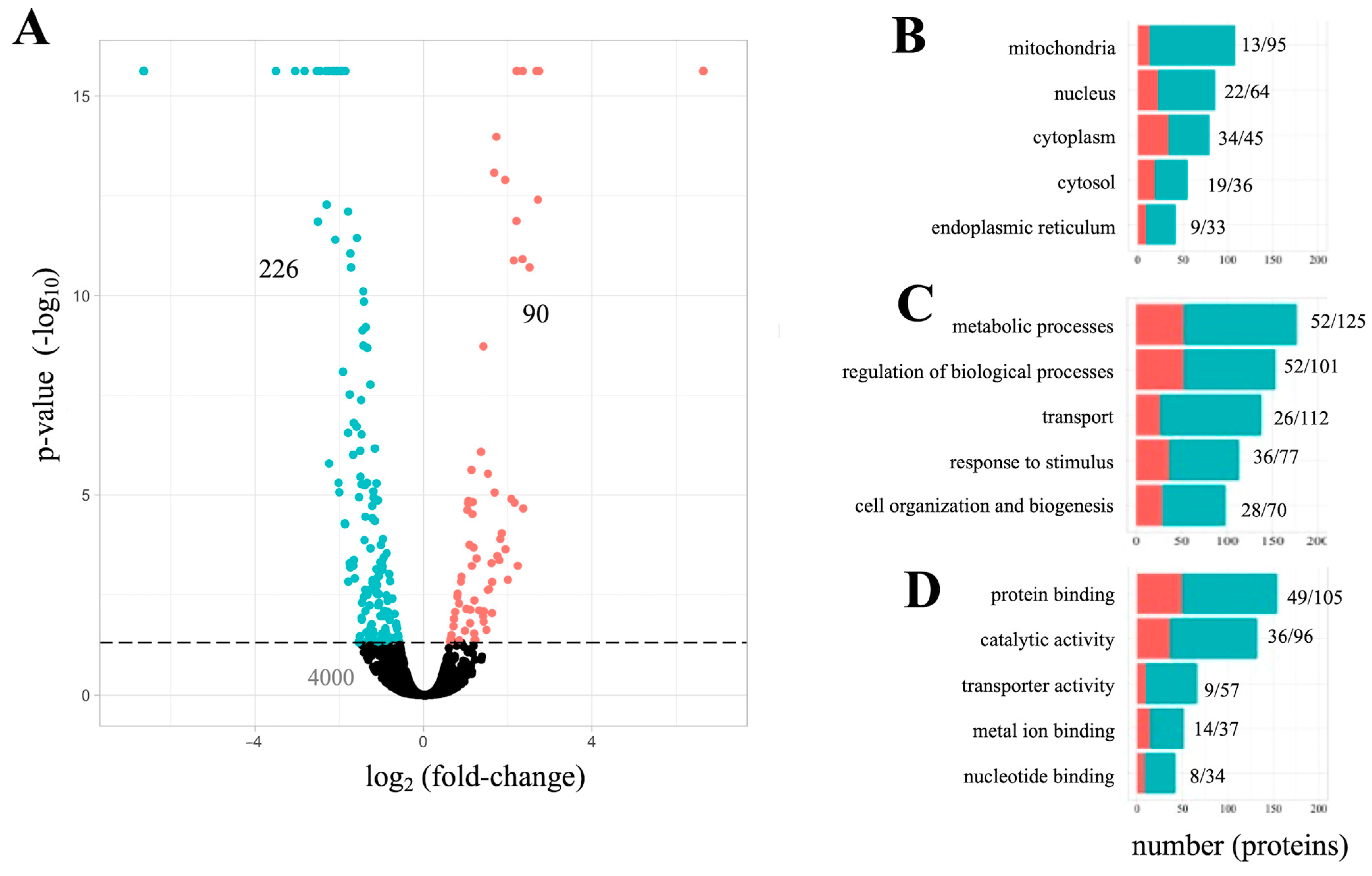

3.1. Whole-Cell Proteome Analysis of PC12 Cells Exposesd to Aβ42

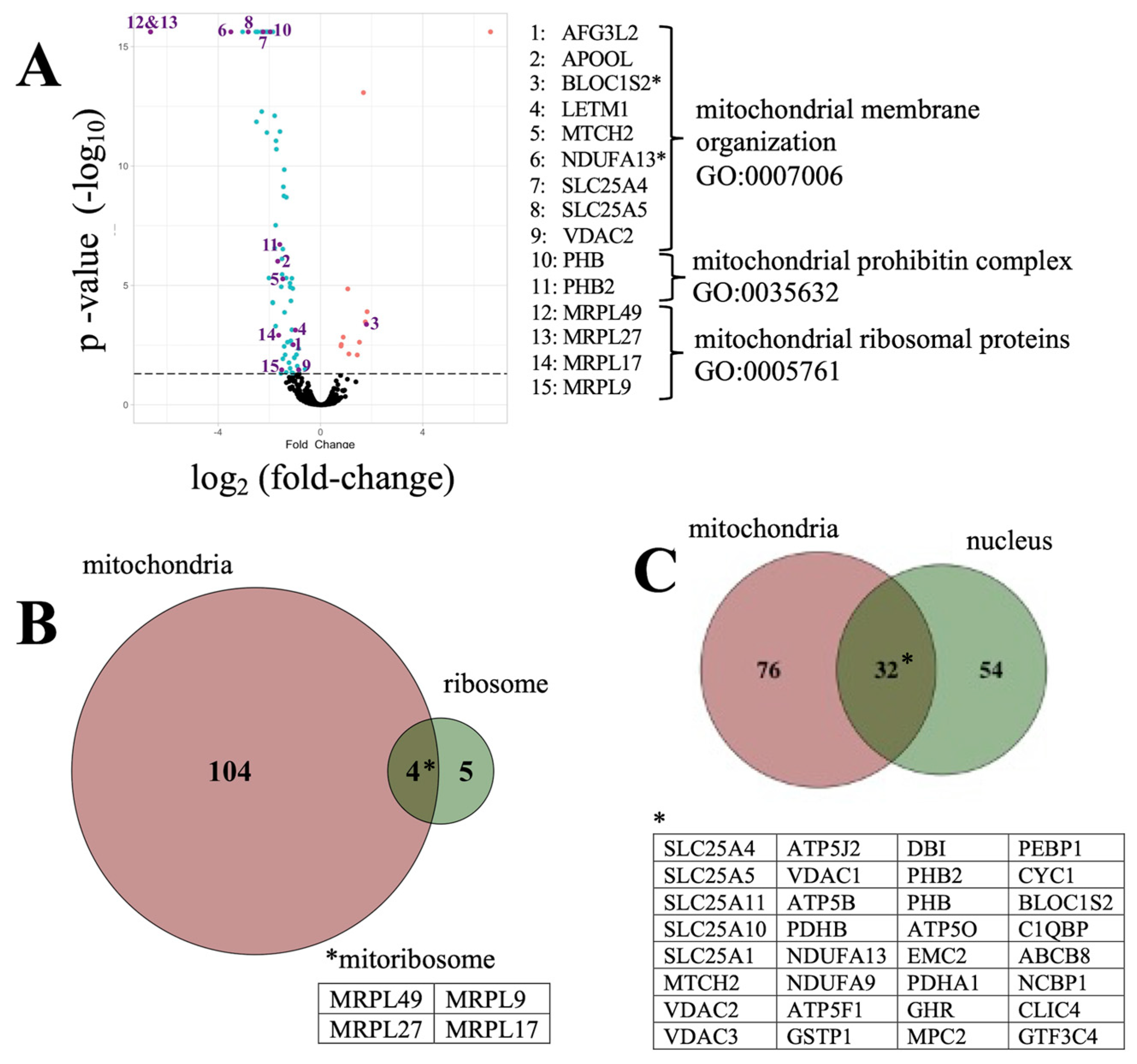

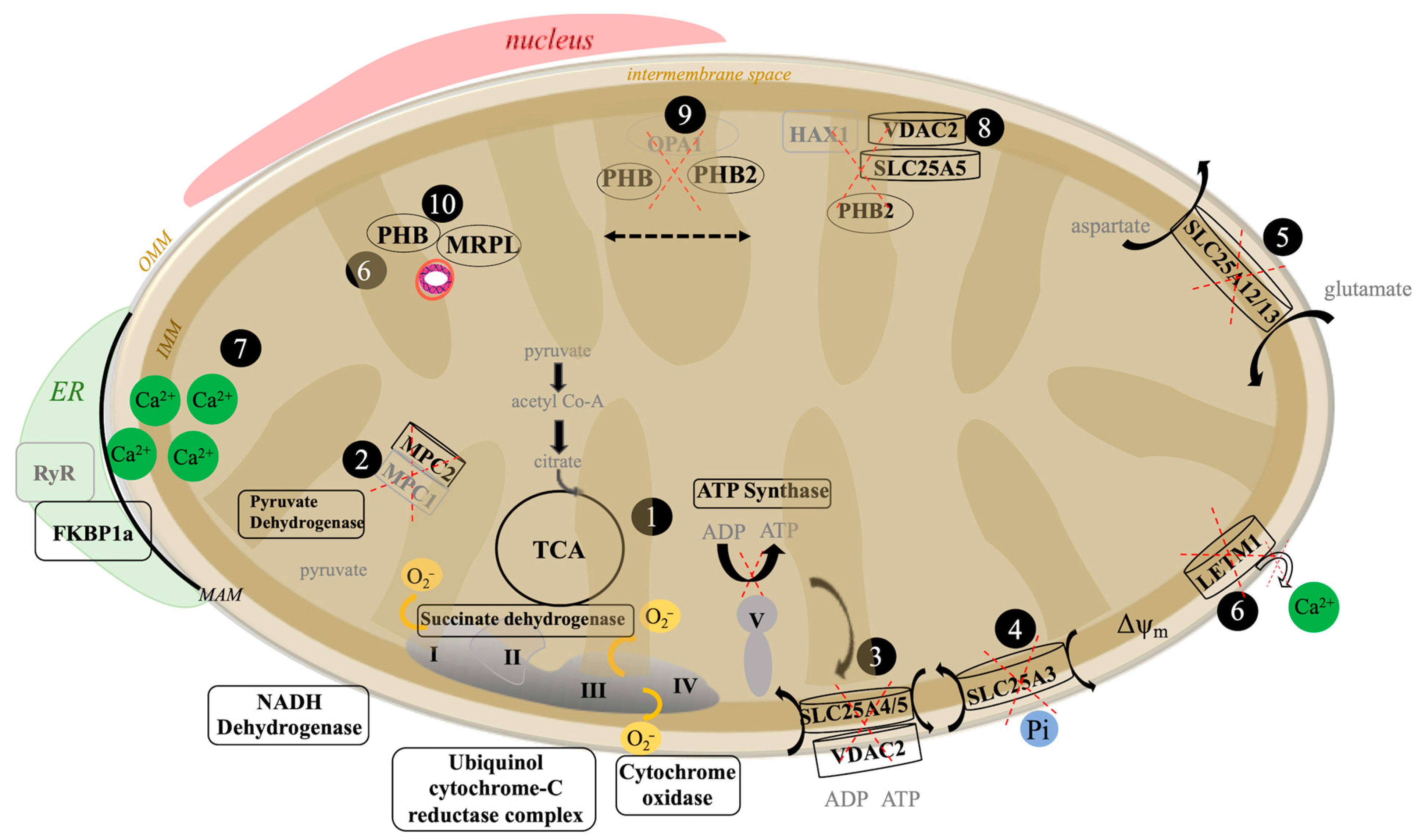

3.2. The Aβ42 Proteome Revolves around Mitochondria Function

3.3. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis of Amyloid-Associated Pathways

3.4. An Analysis of Aβ42 Proteome Associated Genes and Possible Relevance to Human Disease

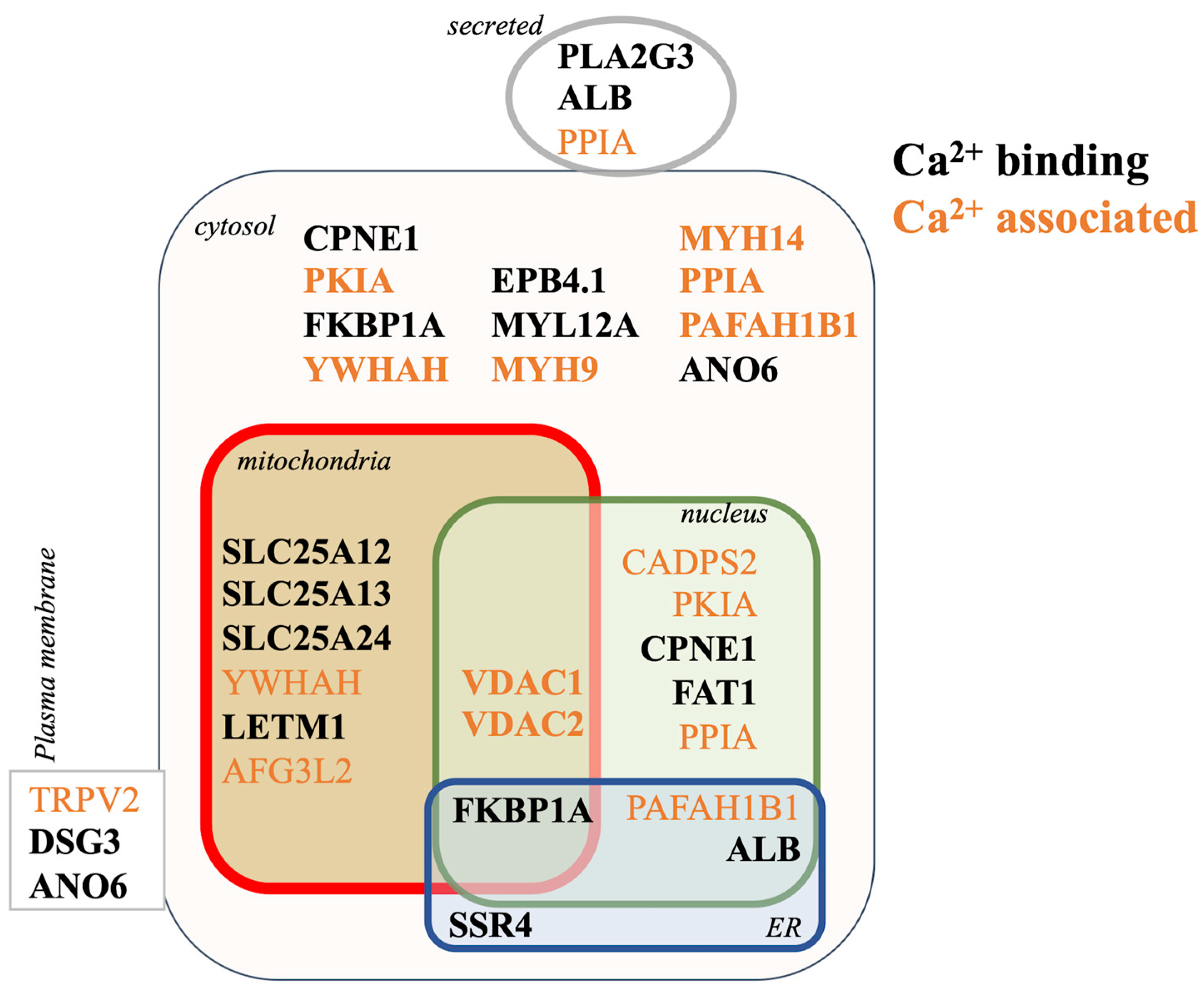

3.5. Proteomic Mechanisms of Aβ42 Cellular Calcium Signaling

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davis, J.; Couch, R. Strategizing the Development of Alzheimer’s Therapeutics. Adv. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2014, 3, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tolar, M.; Abushakra, S.; Hey, J.A.; Porsteinsson, A.; Sabbagh, M. Aducanumab, Gantenerumab, BAN2401, and ALZ-801—the First Wave of Amyloid-Targeting Drugs for Alzheimer’s Disease with Potential for near Term Approval. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perl, D.P. Neuropathology of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Transl. Pers. Med. 2010, 77, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, V.W.; Mattson, M.P.; Wong, P.C.; Gleichmann, M. An Overview of APP Processing Enzymes and Products. Neuromol. Med. 2010, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimas Almeida, C.; Sadat Mirfakhar, F.; Perdigão, C.; Burrinha, T. Impact of Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Genetic Risk Factors on Beta-Amyloid Endocytic Production. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 2577–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.-L.; Yang, F.; Rosario, E.R.; Ubeda, O.J.; Beech, W.; Gant, D.J.; Chen, P.P.; Hudspeth, B.; Chen, C.; Zhao, Y.; et al. β-Amyloid Oligomers Induce Phosphorylation of Tau and Inactivation of Insulin Receptor Substrate via c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase Signaling: Suppression by Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Curcumin. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 9078–9089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koistinaho, M.; Ort, M.; Cimadevilla, J.M.; Vondrous, R.; Cordell, B.; Koistinaho, J.; Bures, J.; Higgins, L.S. Specific Spatial Learning Deficits Become Severe with Age in β-Amyloid Precursor Protein Transgenic Mice That Harbor Diffuse β-Amyloid Deposits but Do Not Form Plaques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 14675–14680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, I.C.; Zimmer, A.R.; Rocha, A.S.; Gosmann, G.; Souza, D.O.; Lourenco, M.V.; Ferreira, S.T.; Zimmer, E.R. Amyloid-β Oligomers in Cellular Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurochem. 2020, 155, 348–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, K.L.; Radford, S.E. Amyloid Plaques beyond Aβ: A Survey of the Diverse Modulators of Amyloid Aggregation. Biophys. Rev. 2017, 9, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.-Q.; Mobley, W.C. Alzheimer Disease Pathogenesis: Insights From Molecular and Cellular Biology Studies of Oligomeric Aβ and Tau Species. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Xu, T.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Melcher, K.; Xu, H.E. Amyloid Beta: Structure, Biology and Structure-Based Therapeutic Development. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2017, 38, 1205–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Cheng, X.; Yi, R.; Gao, D.; Xiong, J. The Binding Receptors of Aβ: An Alternative Therapeutic Target for Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A.; Das, B.; Yao, A.Y.; Yan, R. Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors in Alzheimer’s Disease Synaptic Dysfunction: Therapeutic Opportunities and Hope for the Future. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 78, 1345–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Waring, J.F.; Gopalakrishnan, M.; Li, J. Role of GSK-3β Activation and A7 NAChRs in Aβ1–42-Induced Tau Phosphorylation in PC12 Cells. J. Neurochem. 2008, 106, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, K.; Belcaid, M.; Lantz, M.J.; Taketa, R.; Nichols, R.A. Transcriptome Profile of Nicotinic Receptor-Linked Sensitization of Beta Amyloid Neurotoxicity. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, G.M.; Tong, M.; Jhun, M.; Arora, K.; Nichols, R.A. β-Amyloid Activates Presynaptic A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors Reconstituted into a Model Nerve Cell System: Involvement of Lipid Rafts. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2010, 31, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordman, J.C.; Kabbani, N. An Interaction between A7 Nicotinic Receptors and a G-Protein Pathway Complex Regulates Neurite Growth in Neural Cells. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 5502–5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magni, R.; Almofee, R.; Yusuf, S.; Mueller, C.; Vuong, N.; Almosuli, M.; Hoang, M.T.; Meade, K.; Sethi, I.; Mohammed, N.; et al. Evaluation of Pathogen Specific Urinary Peptides in Tick-Borne Illnesses. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Grolemund, G. R for Data Science: Import, Tidy, Transform, Visualize, and Model Data, 1st ed.; O’Reilly: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4919-1039-9. [Google Scholar]

- Forest, K.H.; Alfulaij, N.; Arora, K.; Taketa, R.; Sherrin, T.; Todorovic, C.; Lawrence, J.L.M.; Yoshikawa, G.T.; Ng, H.-L.; Hruby, V.J.; et al. Protection against β-Amyloid Neurotoxicity by a Non-Toxic Endogenous N-Terminal β-Amyloid Fragment and Its Active Hexapeptide Core Sequence. J. Neurochem. 2018, 144, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shweiki, M.R.; Mönchgesang, S.; Majovsky, P.; Thieme, D.; Trutschel, D.; Hoehenwarter, W. Assessment of Label-Free Quantification in Discovery Proteomics and Impact of Technological Factors and Natural Variability of Protein Abundance. J. Proteome Res. 2017, 16, 1410–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramov, A.Y.; Canevari, L.; Duchen, M.R. Beta-Amyloid Peptides Induce Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Astrocytes and Death of Neurons through Activation of NADPH Oxidase. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasashima, K.; Ohta, E.; Kagawa, Y.; Endo, H. Mitochondrial Functions and Estrogen Receptor-Dependent Nuclear Translocation of Pleiotropic Human Prohibitin 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 36401–36410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, A.; Zhang, F.; Cao, H.; Baranova, A.; Slavin, M. In Silico Gene Set and Pathway Enrichment Analyses Highlight Involvement of Ion Transport in Cholinergic Pathways in Autism: Rationale for Nutritional Intervention. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 648410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadiya, P.; Kolmetzky, D.W.; Tomar, D.; Di Meco, A.; Lombardi, A.A.; Lambert, J.P.; Luongo, T.S.; Ludtmann, M.H.; Praticò, D.; Elrod, J.W. Impaired Mitochondrial Calcium Efflux Contributes to Disease Progression in Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rui, Y.; Tiwari, P.; Xie, Z.; Zheng, J.Q. Acute Impairment of Mitochondrial Trafficking by β-Amyloid Peptides in Hippocampal Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 10480–10487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, T.Q.; van Zomeren, K.C.; Ferrari, M.F.R.; Boddeke, H.W.G.M.; Copray, J.C.V.M. Impairment of Mitochondria Dynamics by Human A53T α-Synuclein and Rescue by NAP (Davunetide) in a Cell Model for Parkinson’s Disease. Exp. Brain Res. 2017, 235, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, F.; Scarcia, P.; Monné, M. Diseases Caused by Mutations in Mitochondrial Carrier Genes SLC25: A Review. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Tan, L.J.; Andoh, D.; Narita, T.; Seki, M.; Hirano, Y.; Narita, K.; Kuraoka, I.; Hiraoka, Y.; Tanaka, K. MMXD, a TFIIH-Independent XPD-MMS19 Protein Complex Involved in Chromosome Segregation. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, V.K.; Zaveri, H.P.; Scott, D.A. 1p36 Deletion Syndrome: An Update. Appl. Clin. Genet. 2015, 8, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertsen, H.; Plaetke, R.; Ballard, L.; Fujimoto, E.; Connolly, J.; Lawrence, E.; Rodriguez, P.; Robertson, M.; Bradley, P.; Milner, B. Genetic Mapping of the BRCA1 Region on Chromosome 17q21. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1994, 54, 516–525. [Google Scholar]

- Mullan, P.B.; Quinn, J.E.; Harkin, D.P. The Role of BRCA1 in Transcriptional Regulation and Cell Cycle Control. Oncogene 2006, 25, 5854–5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Z.S.; Neugebauer, V.; Dineley, K.T.; Kayed, R.; Zhang, W.; Reese, L.C.; Taglialatela, G. α-Synuclein Oligomers Oppose Long-Term Potentiation and Impair Memory through a Calcineurin-Dependent Mechanism: Relevance to Human Synucleopathic Diseases: Cognitive Effects of α-Synuclein Oligomers. J. Neurochem. 2012, 120, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Ogunbunmi, E.M.; Freund, E.A.; Timerman, A.P.; Fleischer, S. FK-Binding Protein Is Associated with the Ryanodine Receptor of Skeletal Muscle in Vertebrate Animals. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 34813–34819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiene-Fischer, C.; Yu, C. Receptor Accessory Folding Helper Enzymes: The Functional Role of Peptidyl Prolyl Cis/Trans Isomerases. FEBS Lett. 2001, 495, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirttimaki, T.M.; Codadu, N.K.; Awni, A.; Pratik, P.; Nagel, D.A.; Hill, E.J.; Dineley, K.T.; Parri, H.R. A7 Nicotinic Receptor-Mediated Astrocytic Gliotransmitter Release: Aβ Effects in a Preclinical Alzheimer’s Mouse Model. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeTure, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The Neuropathological Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nixon, R.A.; Wegiel, J.; Kumar, A.; Yu, W.H.; Peterhoff, C.; Cataldo, A.; Cuervo, A.M. Extensive Involvement of Autophagy in Alzheimer Disease: An Immuno-Electron Microscopy Study. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2005, 64, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John Peter, A.T.; Lachmann, J.; Rana, M.; Bunge, M.; Cabrera, M.; Ungermann, C. The BLOC-1 Complex Promotes Endosomal Maturation by Recruiting the Rab5 GTPase-Activating Protein Msb3. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 201, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, P.J.; Steinberg, F. To Degrade or Not to Degrade: Mechanisms and Significance of Endocytic Recycling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 679–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, M.; Ahumada-Castro, U.; Sanhueza, M.; Gonzalez-Billault, C.; Court, F.A.; Cárdenas, C. Mitochondria and Calcium Regulation as Basis of Neurodegeneration Associated with Aging. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtovich, A.P.; Smith, C.O.; Haynes, C.M.; Nehrke, K.W.; Brookes, P.S. Physiological Consequences of Complex II Inhibition for Aging, Disease, and the MKATP Channel. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1827, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorova, L.D.; Popkov, V.A.; Plotnikov, E.Y.; Silachev, D.N.; Pevzner, I.B.; Jankauskas, S.S.; Babenko, V.A.; Zorov, S.D.; Balakireva, A.V.; Juhaszova, M.; et al. Mitochondrial Membrane Potential. Anal. Biochem. 2018, 552, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCommis, K.S.; Finck, B.N. Mitochondrial Pyruvate Transport: A Historical Perspective and Future Research Directions. Biochem. J. 2015, 466, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevrollier, A.; Loiseau, D.; Reynier, P.; Stepien, G. Adenine Nucleotide Translocase 2 Is a Key Mitochondrial Protein in Cancer Metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2011, 1807, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| GO ID # | Pathway Name | p-Value | # Entities Overlap |

|---|---|---|---|

| BIOLOGICAL PROCESS | |||

| GO:0051503 | adenine nucleotide transport | 2.41 × 10−2 | 8 |

| GO:0015868 | purine ribonucleotide transport | 2.41 × 10−2 | 8 |

| GO:0015865 | purine nucleotide transport | 2.41 × 10−2 | 8 |

| GO:0006862 | nucleotide transport | 2.41 × 10−2 | 8 |

| GO:1902475 | L-alpha-amino acid transmembrane transport | 1.97 × 10−2 | 5 |

| GO:1903825 | organic acid transmembrane transport | 4.85 × 10−2 | 11 |

| GO:1905039 | carboxylic acid transmembrane transport | 4.85 × 10−2 | 11 |

| GO:0015748 | organophosphate ester transport | 3.71 × 10−2 | 12 |

| GO:0001889 | liver development | 4.33 × 10−2 | 6 |

| GO:1901565 | organonitrogen compound catabolic process | 4.10 × 10−2 | 18 |

| GO:0032774 | RNA biosynthetic process | 3.83 × 10−2 | 10 |

| GO:2000113 | negative regulation of cellular macromolecule biosynthetic process | 4.64 × 10−2 | 19 |

| GO:0045892 | negative regulation of transcription, DNA-templated | 3.94 × 10−2 | 15 |

| GO:0051252 | regulation of RNA metabolic process | 3.47 × 10−2 | 44 |

| CELLULAR COMPONENT | |||

| GO:0005762 | mitochondrial large ribosomal subunit | 4.86 × 10−2 | 5 |

| GO:0000315 | organellar large ribosomal subunit | 4.86 × 10−2 | 5 |

| GO:0005840 | ribosome | 2.88 × 10−2 | 8 |

| GO:0098687 | chromosomal region | 1.52 × 10−2 | 6 |

| GO:1990904 | ribonucleoprotein complex | 2.32 × 10−2 | 14 |

| GO:0000785 | chromatin | 6.42 × 10−3 | 8 |

| MOLECULAR FUNCTION | |||

| GO:0000295 | adenine nucleotide transmembrane transporter activity | 2.41 × 10−2 | 8 |

| GO:0015216 | purine nucleotide transmembrane transporter activity | 2.41 × 10−2 | 8 |

| GO:0015215 | nucleotide transmembrane transporter activity | 2.41 × 10−2 | 8 |

| GO:0005346 | purine ribonucleotide transmembrane transporter activity | 2.65 × 10−2 | 7 |

| GO:0015605 | organophosphate ester transmembrane transporter activity | 2.41 × 10−2 | 8 |

| GO:0015932 | nucleobase-containing compound transmembrane transporter activity | 2.41 × 10−2 | 8 |

| GO:1901505 | carbohydrate derivative transmembrane transporter activity | 2.65 × 10−2 | 7 |

| GO:0008514 | organic anion transmembrane transporter activity | 4.34 × 10−2 | 13 |

| GO:0008134 | transcription factor binding | 3.53 × 10−2 | 8 |

| GO:0016772 | transferase activity, transferring phosphorus-containing groups | 1.40 × 10−2 | 9 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sinclair, P.; Baranova, A.; Kabbani, N. Mitochondrial Disruption by Amyloid Beta 42 Identified by Proteomics and Pathway Mapping. Cells 2021, 10, 2380. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10092380

Sinclair P, Baranova A, Kabbani N. Mitochondrial Disruption by Amyloid Beta 42 Identified by Proteomics and Pathway Mapping. Cells. 2021; 10(9):2380. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10092380

Chicago/Turabian StyleSinclair, Patricia, Ancha Baranova, and Nadine Kabbani. 2021. "Mitochondrial Disruption by Amyloid Beta 42 Identified by Proteomics and Pathway Mapping" Cells 10, no. 9: 2380. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10092380

APA StyleSinclair, P., Baranova, A., & Kabbani, N. (2021). Mitochondrial Disruption by Amyloid Beta 42 Identified by Proteomics and Pathway Mapping. Cells, 10(9), 2380. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10092380