ANNEXIN A1: Roles in Placenta, Cell Survival, and Nucleus

Abstract

:1. Introduction

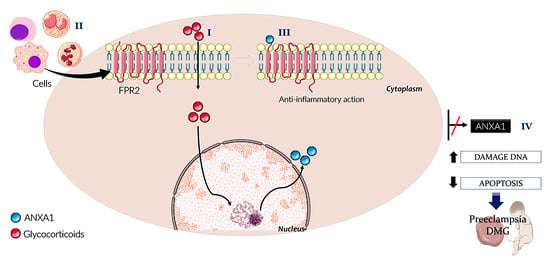

2. ANXA1 and Inflammatory Processes

3. ANXA1 in the Placenta

4. ANXA1 and Cell Survival

5. ANXA1 in the Nucleus

| ANXA1 in Nucleus | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model | Functions | Ref. |

| Ischemia-reperfusion injury | Nuclear translocation induced neuron and retinal ganglion cell apoptosis | [85,86,87] |

| Ischemic stroke | Nuclear translocation reduced BID expression and inhibited the activation of the caspase-3 apoptotic pathway, attenuating neuronal apoptosis | [88] |

| Cellular stress | Gene expression levels increased, and translocation of annexin I from the cytoplasm to the nucleus initiated, in cells treated under stress conditions | [90] |

| Oral and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | Patients with low nuclear ANXA1 expression had better prognoses than those with high protein expression | [67,91] |

| Gastric adenocarcinoma | Nuclear location correlated with the advanced stage of the disease and peritoneal dissemination | [92] |

6. Perspective and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flower, R.; Gaddum, E. Lipocortin and the mechanism of action of the glucocorticoids. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988, 94, 987–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perretti, M.; Gavins, F. Annexin 1: An endogenous anti- inflammatory protein. Physiology 2003, 18, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, T.Z.; Mues, G.I. Human lipocortin similar to ras gene products. Nature 1986, 322, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarbe, M.A.; Barrasa, J.I.; Olmo, N.; Gavilanes, F.; Turnay, J. Annexin-phospholipid interactions. Functional implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 2652–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berg Klenow, M.; Iversen, C.; Wendelboe Lund, F.; Mularski, A.; Busk Heitmann, A.S.; Dias, C.; Nylandsted, J.; Simonsen, A.C. Annexins A1 and A2 Accumulate and Are Immobilized at Cross-Linked Membrane–Membrane Interfaces. Biochemistry 2021, 60, 1248–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, A.K.; Rescher, U.; Gerke, V.; McNeil, P.L. Requirement for Annexin A1 in Plasma Membrane Repair. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 35202–35207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raynal, P.; Pollard, H.B. Annexins: The problem of assessing the biological role for a gene family of multifunctional calcium-and phospholipid-binding proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Rev. Biomembr. 1994, 1, 63–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’acquisto, F.; Perretti, M.; FLOWER, R.J. Annexin-A1: A pivotal regulator of the innate and adaptive immune systems. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 155, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hannon, R.; Croxtall, J.D.; Getting, S.J.; Roviezzo, F.; Yona, S.; Paul-Clark, M.J.; Gavins, F.N.; Perretti, M.; Morris, J.F.; Buckingham, J.C.; et al. Aberrant inflammation and resistance to glucocorticoids in annexin 1−/− mouse. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 253–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parente, L.; Solito, E. Annexin 1: More than an anti-phospholipase protein. Inflamm. Res. 2004, 4, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenes, A.D.; Andrade, T.R.M.; Mello, C.B.; Ramos, L.; Gil, C.D.; Oliani, S.M. Beneficial effect of annexin A1 in a model of experimental allergic conjunctivitis. Exp. Eye Res. 2015, 134, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, M.A.; Vago, J.P.; Teixeira, M.M.; Sousa, L.P. Annexin A1 and the resolution of inflammation: Modulation of neutrophil recruitment, apoptosis, and clearance. J. Immunol. Res. 2016, 2016, 8239258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Paula-Silva, M.; Barrios, B.E.; Macció-Maretto, L.; Sena, A.A.; Farsky, S.H.; Correa, S.G.; Oliani, S.M. Role of the protein annexin A1 on the efficacy of anti-TNF treatment in a murine model of acute colitis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016, 115, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Teixeira, R.A.P.; Mimura, K.K.; Araujo, L.P.; Greco, K.V.; Oliani, S.M. The essential role of annexin A1 mimetic peptide in the skin allograft survival. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2016, 10, E44–E53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinniah, A.; Yazid, S.; Bena, S.; Oliani, S.M.; Perretti, M.; Flower, R.J. Endogenous annexin-A1 negatively regulates mast cell-mediated allergic reactions. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, P.F.; Che, X.D.; Li, H.Z.; Gao, Y.Y.; Wei, X.C.; Li, P.C. Annexin A1 involved in the regulation of inflammation and cell signaling pathways. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2020, 23, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ma, W.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Li, H.; He, F. ANXA1 enhances tumor proliferation and migration by regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition and IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 pathway in papillary thyroid carcinoma. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 1295–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.H.; Solito, E. Annexin A1: Uncovering the many talents of an old protein. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gavins, F.N.E.; Dalli, J.; Flower, R.J.; Granger, D.N.; Perretti, M. Activation of the annexin 1 counter-regulatory circuit affords protection in the mouse brain microcirculation. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 1751–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facio, F.N., Jr.; Sena, A.A.; Araújo, L.P.; Mendes, G.E.; Castro, I.; Luz, M.A.; Yu, L.; Oliani, S.M.; Burdmann, E.A. Annexin 1 mimetic peptide protects against renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. J. Mol. Med. 2011, 89, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.B.; Kornerup, K.N.; Sampaio, A.L.; D’Acquisto, F.; Seed, M.P.; Girol, A.P. The impact of endogenous annexin A1 on glucocorticoid control of inflammatory arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012, 71, 1872–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lacerda, J.Z.; Drewes, C.C.; Mimura, K.K.O.; Zanon, C.F.; Ansari, T.; Gil, C.D. Annexin A12-26 treatment improves skin heterologous transplantation by modulating inflammation and angiogenesis processes. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cardin, L.T.; Sonehara, N.M.; Mimura, K.K.O.; Dos Santos, A.R.D.; da Silva Junior, W.A.; Sobral, L.M.; Leopoldino, A.M.; Cunha, B.R.; Tajara, E.H.; Oliani, S.M. Annexin A1 peptide and endothelial cell-conditioned medium modulate cervical tumorigenesis. FEBS Open Bio 2019, 9, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmorato, M.P.; Gimenes, A.D.; Andrade, F.E.C.; Oliani, S.M.; Gil, C.D. Involvement of the annexin A1-Fpr anti-inflammatory system in the ocular allergy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 842, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prates, J.; Moreli, J.B.; Gimenes, A.D.; Biselli, J.M.; Pires D’Avila, S.; Sandri, S.; Farsky, S.; Rodrigues-Lisoni, F.C.; Oliani, S.M. Cisplatin treatment modulates Annexin A1 and inhibitor of differentiation to DNA 1 expression in cervical cancer cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 129, 110331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, F.W.; Rikhi, A.; Wan, S.H.; Iyer, S.R.; Chakraborty, H.; McNulty, S.; Tang, W.; Felker, G.M.; Givertz, M.M.; Chen, H.H. Annexin A1 is a Potential Novel Biomarker of Congestion in Acute Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2020, 26, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yu, C.; Luo, J.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, C.; Zhang, H. The Role and Mechanism of the annexin A1 Peptide Ac2-26 in rats with cardiopulmonary bypass Lung injury. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2021, 128, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatelli, I.; Sutti, S.; Jindal, A.; Vacchiano, M.; Bozzola, C.; Reutelingsperger, C.; Kusters, D.; Bena, S.; Parola, M.; Paternostro, C.; et al. Endogenous Annexin A1 Is a Novel Protective Determinant in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in Mice. Hepatology 2014, 60, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferraro, B.; Leoni, G.; Hinkel, R.; Ormanns, S.; Paulin, N.; Ortega-Gomez, A.; Viola, J.R.; de Jong, R.; Bongiovanni, D.; Bozoglu, T.; et al. Pro-Angiogenic Macrophage Phenotype to Promote Myocardial Repair. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 2990–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, S.; Juban, G.; Gobbetti, T.; Desgeorges, T.; Theret, M.; Gondin, J.; Toller-Kawahisa, J.E.; Reutelingsperger, C.P.; Chazaud, B.; Perretti, M.; et al. Annexin A1 Drives Macrophage Skewing to Accelerate Muscle Regeneration through AMPK Activation. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 1156–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanches, J.M.; Correia-Silva, R.D.; Duarte, G.; Fernandes, A.; Sánchez-Vinces, S.; Carvalho, P.O.; Oliani, S.M.; Bortoluci, K.R.; Moreira, V.; Gil, C.D. Role of Annexin A1 in NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Murine Neutrophils. Cells 2021, 10, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuqui, B.; De Paula-Silva, M.; Carlos, C.P.; Ullah, A.; Arni, R.K.; Gil, C.D.; Oliani, S.M. Ac2-26 Mimetic Peptide of Annexin A1 Inhibits Local and Systemic Inflammatory Processes induced by Bothrops moojeni venom and the Lys- 49 phospholipase A2 in a rat model. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oliani, S.M.; Paul-Clark, M.J.; Christian, H.C.; Flower, R.J.; Perretti, M. Neutrophil Interaction with Inflamed Postcapillary Venule Endothelium Alters Annexin 1 Expression. Am. J. Pathol. 2001, 158, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliani, S.M.; Ciocca, G.A.; Pimentel, T.A.; Damazo, A.S.; Gibbs, L.; Perretti, M. Fluctuation of annexin-A1 positive mast cells in chronic granulomatous inflammation. Inflamm. Res. 2008, 57, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.B.; Mimura, K.; Freitas, A.A.; Hungria, E.M.; Sousa, A.; Oliani, S.M.; Stefani, M. Mast cell heterogeneity and anti-inflammatory annexin A1 expression in leprosy skin lesions. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 118, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parisi, J.; Corrêa, M.; Gil, C. Lack of endogenous Annexin A1 increases mast cell activation and exacerbates experimental atopic dermatitis. Cells 2019, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliani, S.M.; Damazo, A.S.; Perretti, M. Annexin 1 localization in tissue eosinophils as detected by electron microscopy. Mediat. Inflamm. 2002, 11, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ng, F.S.; Wong, K.Y.; Guan, S.P. Annexin-1-deficient mice exhibit spontaneous airway hyperresponsiveness and exacerbated allergen-specific antibody responses in a mouse model of asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2011, 41, 1793–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solito, E.; Romero, I.; Marullo, S.; Russo-Marie, F.; Weksler, B. Annexin 1 binds to U937 monocytic cells and inhibits their adhesion to microvascular endothelium: Involvement of the α4β1 integrin. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 1573–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bergström, I.; Lundberg, A.K.; Jönsson, S.; Särndahl, E.; Ernerudh, J.; Jonasson, L. Annexin A1 in blood mononuclear cells from patients with coronary artery disease: Its association with inflammatory status and glucocorticoid sensitivity. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ribeiro, A.; Caloi, C.; Pimenta, S.; Seshayyan, S.; Govindarajulu, S.; Souto, F.; Damazo, A. Expression of annexin-A1 in blood and tissue leukocytes of leprosy patients. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2020, 53, e20200277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, P. Interaction between ANXA1 and GATA-3 in Immunosuppression of CD4+ T Cells. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 1701059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liang, Z.; Li, X. Identification of ANXA1 as a potential prognostic biomarker and correlating with immune infiltrates in colorectal cancer. Autoimmunity 2021, 2, 7–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gastardelo, T.S.; Cunha, B.R.; Raposo, L.S. Inflammation and cancer: Role of annexin A1 and FPR2/ALX in proliferation and metastasis in human laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Perretti, M.; Getting, S.J.; Solito, E.; Murphy, P.M.; Gao, J.-L. Involvement of the Receptor for Formylated Peptides in the in Vivo Anti-Migratory Actions of Annexin 1 and Its Mimetics. Am. J. Pathol. 2001, 158, 1969–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ernst, S.; Lange, C.; Wilbers, A.; Goebeler, V.; Gerke, V.; Rescher, U. An Annexin 1 N-Terminal Peptide Activates Leukocytes by Triggering Different Members of the Formyl Peptide Receptor Family. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 7669–7676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gavins, F.N.; Yona, S.; Kamal, A.M.; Flower, R.J.; Perretti, M. Leukocyte antiadhesive actions of annexin 1: ALXR- and FPR-related anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Blood 2003, 101, 4140–4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perretti, M.; Godson, C. Formyl peptide receptor type 2 agonists to kick-start resolution pharmacology. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 4595–4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headland, S.E.; Norling, L.V. The resolution of inflammation: Principles and challenges. Semin. Immunol. 2015, 27, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headland, S.E.; Jones, H.R.; Norling, L.V. Neutrophil-derived microvesicles enter cartilage and protect the joint in inflammatoryarthritis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 315ra190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molás, R.B.; De Paula-Silva, M.; Masood, R.; Ullah, A.; Gimenes, A.D.; Oliani, S.M. Ac2-26 peptide and serine protease of Bothrops atrox similarly induces angiogenesis without triggering local and systemic inflammation in a murine model of dorsal skinfold chamber. Toxicon 2017, 137, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Oliveira Cardoso, M.F.; Moreli, J.B.; Gomes, A.O.; De Freitas Zanon, C.; Silva, A.E.; Paulesu, L.R. Annexin A1 peptide is able to induce an anti-parasitic effect in human placental explants infected by Toxoplasma gondii. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 123, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Molás, R.B.; Ribeiro, M.R.; Ramalho Dos Santos, M.J.C. The involvement of annexin A1 in human placental response to maternal Zika virus infection. Antiviral Res. 2020, 179, 104809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauster, M.; Desoye, G.; Tötsch, M.; Hiden, U. The placenta and gestational diabetes mellitus. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2012, 12, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Liu, Y.; Gibb, W. Distribution of annexin I and II in term human fetal membranes, decidua and placenta. Placenta 1996, 17, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myatt, L.; Hirth, J.; Everson, W.V. Changes in annexin (lipocortin) content in human amnion and chorion at parturition. J. Cell. Biochem. 1992, 50, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebeda, C.B.; Sandri, S.; Benis, C.M.; Paula-Silva, M.; Loiola, R.A.; Reutelingsperger, C.; Perretti, M.; Farsky, S.H.P. Annexin A1/Formyl Peptide Receptor Pathway Controls Uterine Receptivity to the Blastocyst. Cells 2020, 9, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreli, J.B.; Hebeda, C.B.; Machado, I.D.; Reif-Silva, I.; Oliani, S.M.; Perretti, M.; Bevilacqua, E.; Farsky, S.H.P. The role of endogenous annexin A1 (AnxA1) in pregnancy. Placenta 2017, 51, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Tang, Z. Silencing of Annexin A1 suppressed the apoptosis and inflammatory response of preeclampsia rat trophoblasts. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 3125–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruikar, K.; Aithal, M.; Shetty, P. Placental Expression and Relative Role of Anti-inflammatory Annexin A1 and Animal Lectin Galectin-3 in the Pathogenesis of Preeclampsia. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2022, 37, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrouz, G.F.; Farzaneh, G.S.; Leila, J.; Jaleh, Z.; Eskandar, K.S. Presence of auto-antibody against two placental proteins, annexin A1 and vitamin D binding protein, in sera of women with pre-eclampsia. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2013, 99, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perucci, L.O.; Carneiro, F.S.; Ferreira, C.N. Annexin A1 Is Increased in the Plasma of Preeclamptic Women. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moreli, J.; Paula-Silva, M.; Calderon, I.; Farsky, S.; Oliani, S.; Bevilacqua, E. Annexin A1 Localization and Relevance in Human Placenta from Pregnancies Complicated by Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Preliminary Results. Placenta 2016, 45, 108–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Lim, W.; Bist, P.; Perumalsamy, R.; Lukman, H.M.; Li, F.; Welker, L.B.; Yan, B.; Sethi, G.; Tambyah, P.A.; et al. Influenza A virus enhances its propagation through the modulation of Annexin-A1 dependent endosomal trafficking and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 1243–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swa, H.L.; Blackstock, W.P.; Lim, L.H.; Gunaratne, J. Quantitative proteomics profiling of murine mammary gland cells unravels impact of annexin-1 on DNA damage response, cell adhesion, and migration. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2012, 11, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vago, J.P.; Nogueira, C.R.; Tavares, L.P. Annexin A1 modulates natural and glucocorticoid-induced resolution of inflammation by enhancing neutrophil apoptosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2012, 92, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Tian, Y.; Duan, B.; Sheng, H.; Gao, H.J. Association of nuclear annexin A1 with prognosis of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 7, 751–759. [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg, E. DNA damage and repair. Nature 2003, 421, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berra, C.; Menck, C.; Mascio, P. Oxidative stress, genome lesions and signaling pathways in cell cycle control. Quím. Nova 2006, 29, 1340–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Su, N.; Xu, X.Y.; Chen, H.; Gao, W.C.; Ruan, C.P.; Wang, Q.; Sun, Y.P. Increased expression of annexin A1 is correlated with K-ras mutation in colorectal cancer. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2010, 222, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nair, S.; Hande, M.P.; Lim, L.H. Annexin-1 protects MCF7 breast cancer cells against heat-induced growth arrest and DNA damage. Cancer Lett. 2010, 294, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, R.M.; Chiganças, V.; Galhardo Rda, S.; Carvalho, H.; Menck, C.F. The eukaryotic nucleotide excision repair pathway. Biochimie 2003, 85, 1083–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hublarova, P.; Greplova, K.; Holcakova, J.; Vojtesek, B.; Hrstka, R. Switching p53-dependent growth arrest to apoptosis via the inhibition of DNA damage-activated kinases. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2010, 15, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgarbosa, F.; Barbisan, L.; Brasil, M.; Costa, E.; Calderon, I.; Gonçalves, C.; Bevilacqua, E.; Rudge, M. Changes in apoptosis and Bcl-2 expression in human hyperglycemic, term placental trophoblast. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2006, 73, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Srivas, R.; Fu, K.Y.; Hood, B.L.; Dost, B.; Gibson, G.A.; Watkins, S.C.; Van Houten, B.; Bandeira, N.; Conrads, T.P.; et al. Quantitative proteomics reveal ATM kinase-dependent exchange in DNA damage response complexes. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 4983–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckanna, J.A. Lipocortin 1 in apoptosis: Mammary regression. Anat. Rec. 1995, 242, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, T.; Repasky, W.; Uchida, K.; Hirata, A.; Hirata, F. Modulation of cell death pathways to apoptosis and necrosis of H2O2-treated rat thymocytes by lipocortin I. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996, 220, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solito, E.; Kamal, A.; Russo-Marie, F.; Buckingham, J.; Marullo, S.; Perretti, M. A novel calcium-dependent proapoptotic effect of annexin 1 on human neutrophils. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 1544–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debret, R.; Btaouri, H.; Duca, L.; Rahman, I.; Radke, S.; Haye, B.; Sallenave, J.; Antonicelli, F. Annexin A1 processing is associated with caspase-dependent apoptosis in BZR cells. FEBS Lett. 2003, 546, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliani, S.M.; Perretti, M. Cell localization of the anti-inflammatory protein annexin 1 during experimental inflammatory response. Ital. J. Anat. Embryol. 2001, 106, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mussunoor, S.; Murray, G.I. The role of annexins in tumour development and progression. J. Pathol. J. Pathol. Soc. G. B. Irel. 2008, 216, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oudhraa, Z.; Bouchon, B.; Viallard, C.; D’incan, M.; Degoul, F. Annexin A1 localization and its relevance to cancer. Clin. Sci. 2016, 130, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, L.H.K.; Pervaiz, S. Annexin 1: The New Face of an Old Molecule. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yuan, Y.; Anbalagan, D.; Lee, L.H.; Samy, R.P.; Shanmugam, M.K.; Kumar, A.P.; Sethi, G.; Lobie, P.E.; Lim, L.H. ANXA1 inhibits miRNA-196a in a negative feedback loop through NF-kB and c-Myc to reduce breast cancer proliferation. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 27007–27020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Gong, J.; Li, L.; Chen, L.; Zheng, L.; Chen, Z.; Shi, J.; Zhang, H. Annexin A1 nuclear translocation induces retinal ganglion cell apoptosis after ischemia-reperfusion injury through the p65/IL-1β pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 1350–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, Y. Ad-and AAV8-mediated ABCA1 gene therapy in a murine model with retinal ischemia/reperfusion injuries. Mol. Ther.-Methods Clin. Dev. 2021, 20, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zheng, L.; Xia, Q.; Liu, L.; Mao, M.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, J. A novel cell-penetrating peptide protects against neuron apoptosis after cerebral ischemia by inhibiting the nuclear translocation of annexin A1. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, Q.; Zheng, L.; Liu, L.; Zhao, B.; Shi, J. Nuclear translocation of annexin 1 following oxygen-glucose deprivation-reperfusion induces apoptosis by regulating Bid expression via p53 binding. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Li, X.; Zhou, H.; Zheng, L.; Shi, J. S100A11protects against neuronal cell apoptosis induced by cerebral ischemia via inhibiting the nuclear translocation of annexin A1. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 9, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, H.; Kim, G.; Huh, J.; Kkim, S.; Na, D. Annexin I is a stress protein induced by heat, oxidative stress and a sulfhydryl-reactive agent. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000, 267, 3220–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, C.Y.; Jeng, Y.M.; Chou, H.Y.; Hsu, H.C.; Yuan, R.H.; Chiang, C.P.; Kuo, M.Y. Nuclear localization of annexin A1 is a prognostic factor in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Surg. Oncol. 2008, 97, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, F.; Xu, C.; Jiang, Z.; Jin, M.; Wang, L.; Zeng, S.; Teng, L.; Cao, J. Nuclear localization of annexin A1 correlates with advanced disease and peritoneal dissemination in patients with gastric carcinoma. Anat. Rec. Adv. Integr. Anat. Evol. Biol. 2010, 293, 1310–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, A.; Corcoran, G.B.; Hirata, F. Carcinogenic heavy metals, As3+ and Cr6+, increase affinity of nuclear mono-ubiquitinated annexin A1 for DNA containing 8-oxo-guanosine, and promote translesion DNA synthesis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011, 252, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sousa, S.O.d.; Santos, M.R.d.; Teixeira, S.C.; Ferro, E.A.V.; Oliani, S.M. ANNEXIN A1: Roles in Placenta, Cell Survival, and Nucleus. Cells 2022, 11, 2057. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11132057

Sousa SOd, Santos MRd, Teixeira SC, Ferro EAV, Oliani SM. ANNEXIN A1: Roles in Placenta, Cell Survival, and Nucleus. Cells. 2022; 11(13):2057. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11132057

Chicago/Turabian StyleSousa, Stefanie Oliveira de, Mayk Ricardo dos Santos, Samuel Cota Teixeira, Eloisa Amália Vieira Ferro, and Sonia Maria Oliani. 2022. "ANNEXIN A1: Roles in Placenta, Cell Survival, and Nucleus" Cells 11, no. 13: 2057. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11132057

APA StyleSousa, S. O. d., Santos, M. R. d., Teixeira, S. C., Ferro, E. A. V., & Oliani, S. M. (2022). ANNEXIN A1: Roles in Placenta, Cell Survival, and Nucleus. Cells, 11(13), 2057. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11132057