LIM Kinases, Promising but Reluctant Therapeutic Targets: Chemistry and Preclinical Validation In Vivo

Abstract

:1. Introduction

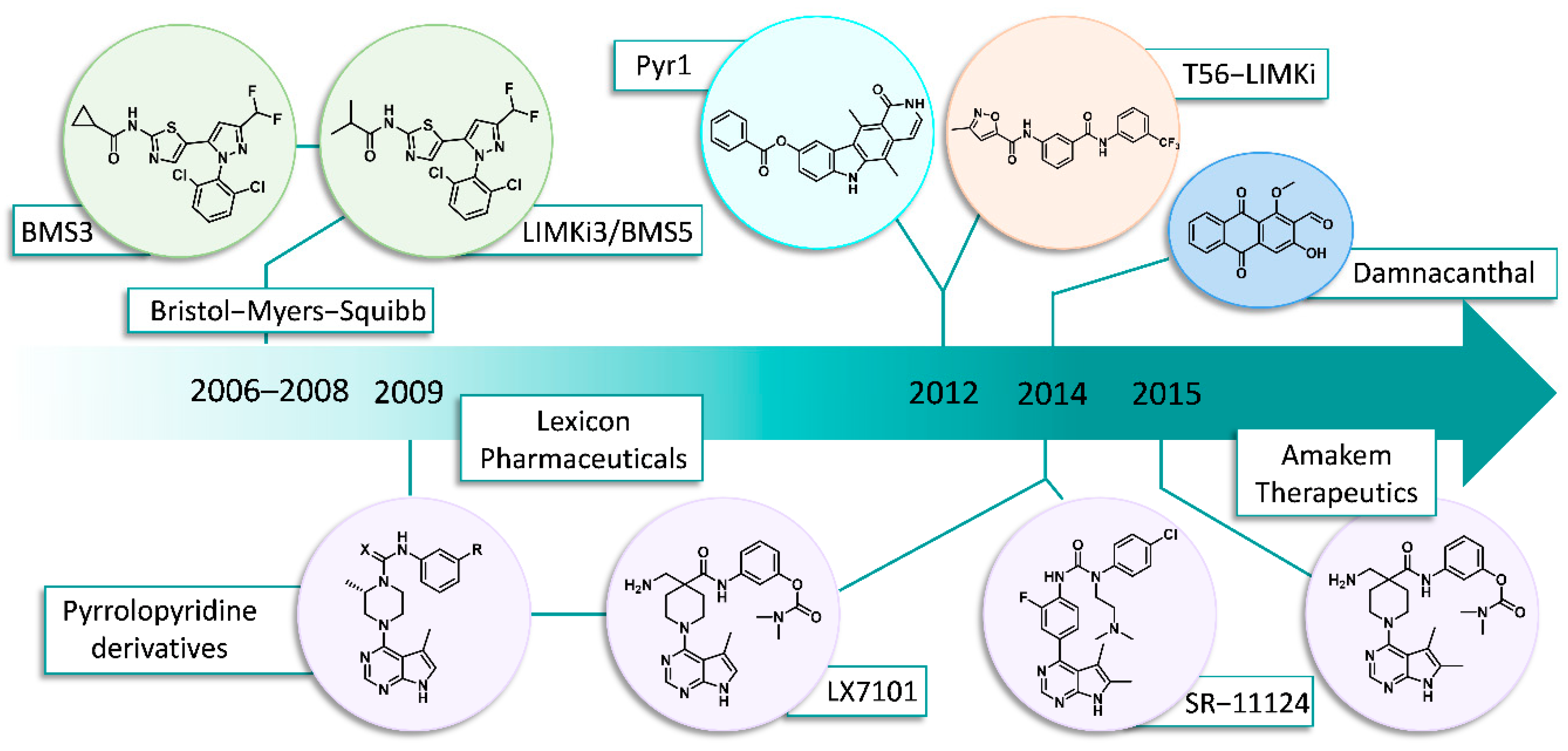

2. Chronology/Overview

2.1. Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS)

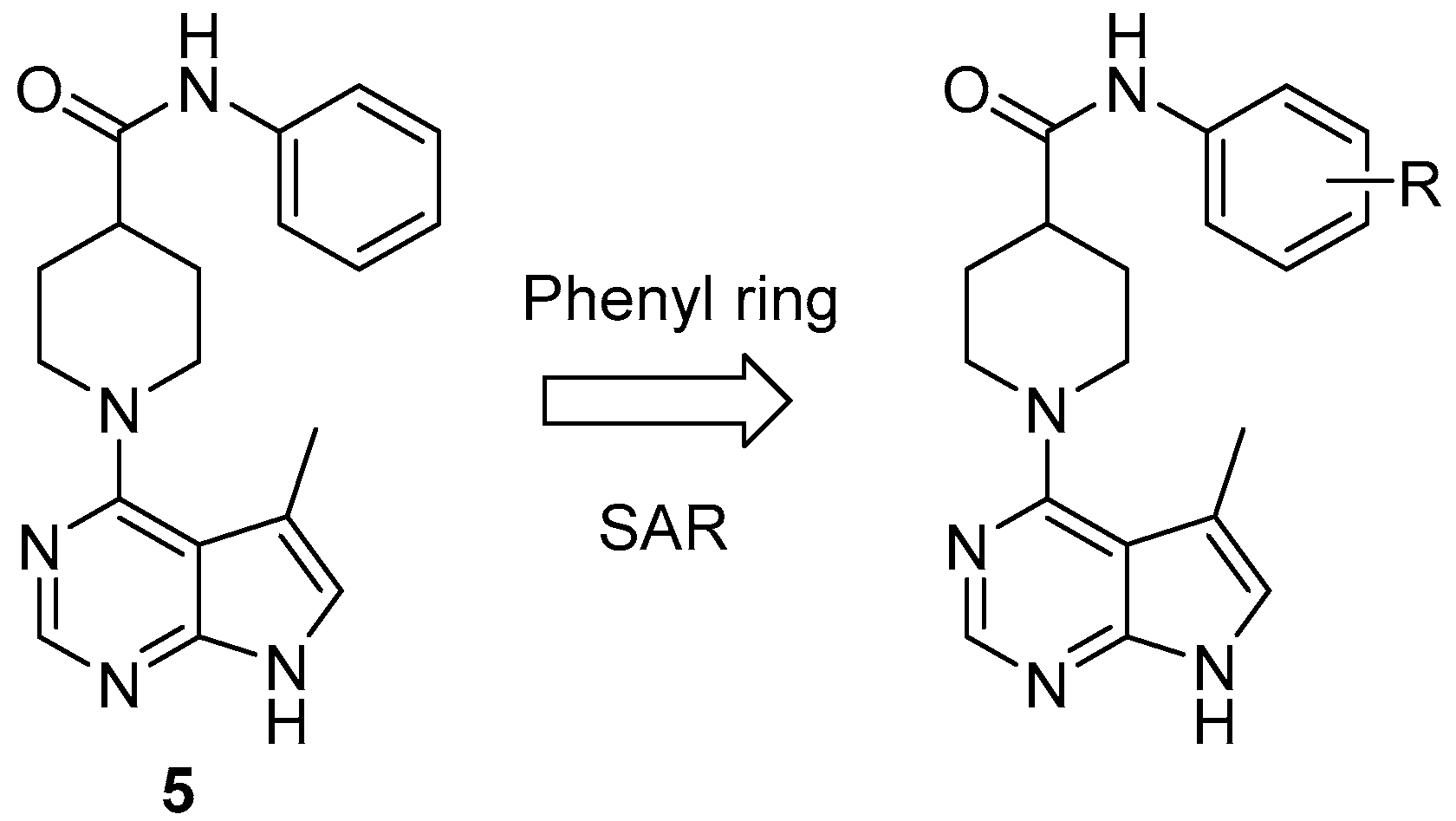

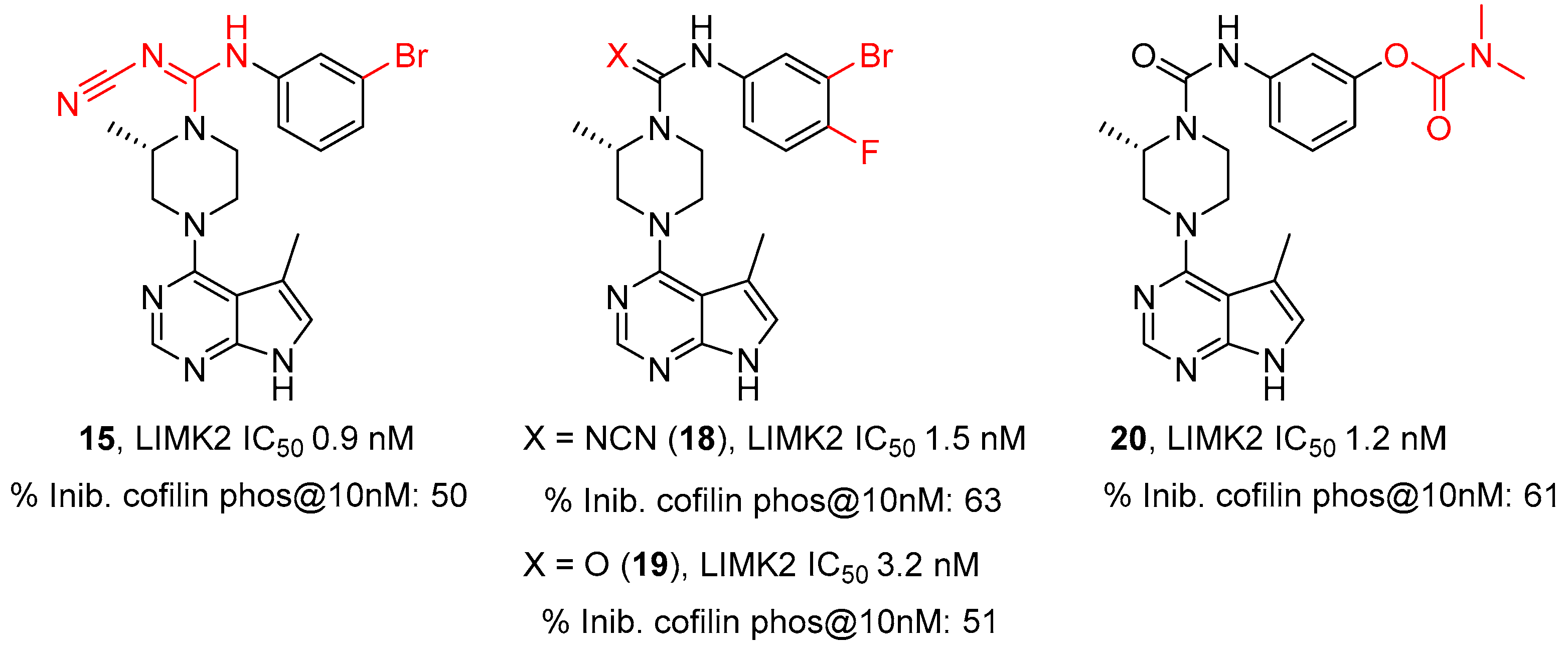

2.2. Lexicon Pharmaceuticals and Amakem Therapeutics

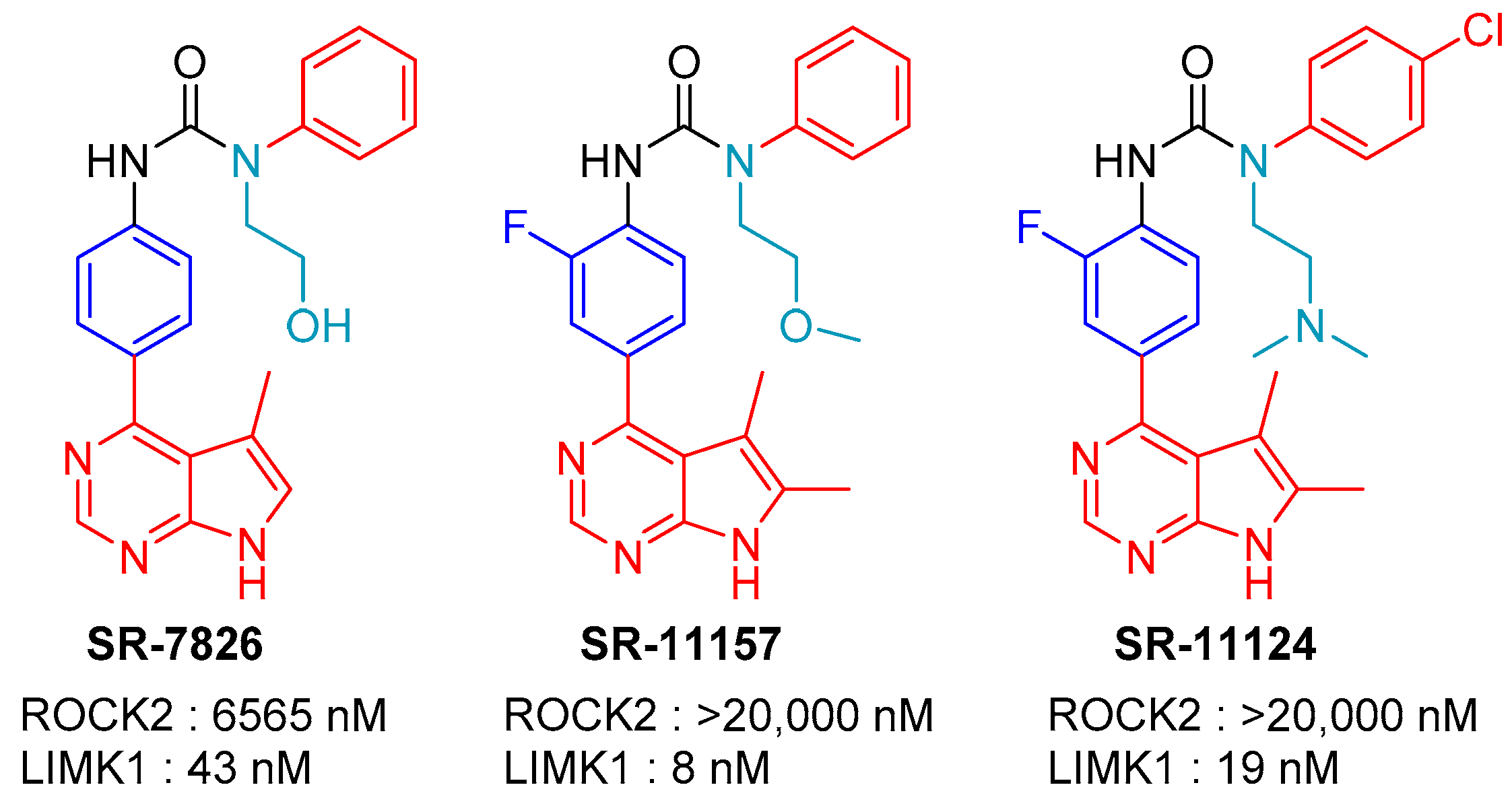

2.3. SR-11124 and SR-7826: Scripps Research Institute, Florida

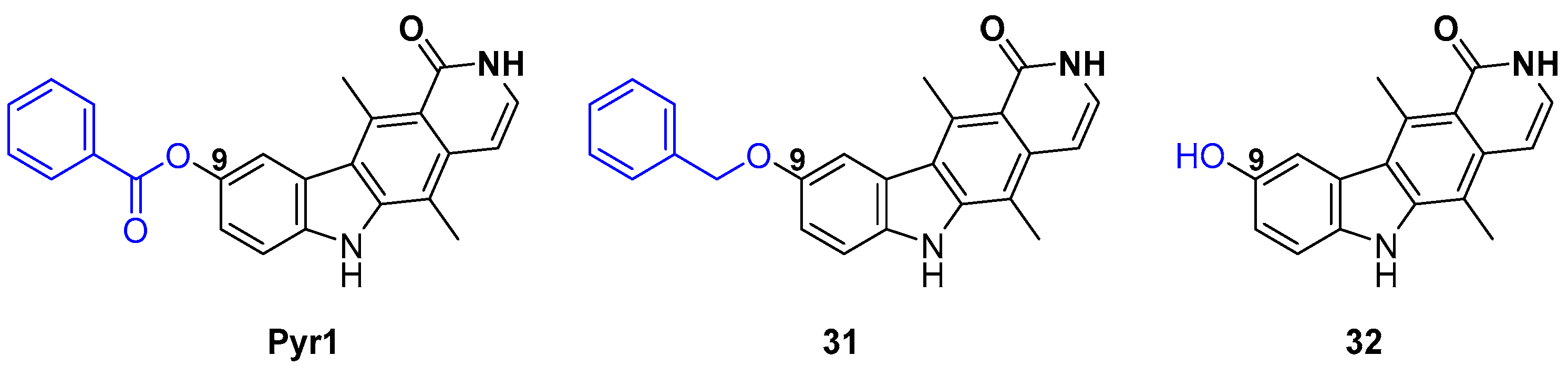

2.4. Pyr1 Derivatives

2.5. T56-LIMKi (T5601640)

2.6. Damnacanthal

2.7. CEL_Amide

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Manetti, F. LIM kinases are attractive targets with many macromolecular partners and only a few small molecule regulators. Med. Res. Rev. 2012, 32, 968–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, R.; Olson, M. LIM kinases: Function, regulation and association with human disease. J. Mol. Med. 2007, 85, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prunier, C.; Prudent, R.; Kapur, R.; Sadoul, K.; Lafanechère, L. LIM kinases: Cofilin and beyond. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 41749–41763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, M.-H.; Kundu, J.K.; Chae, J.-I.; Shim, J.-H. Targeting ROCK/LIMK/cofilin signaling pathway in cancer. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2019, 42, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acevedo, K.; Li, R.; Soo, P.; Suryadinata, R.; Sarcevic, B.; Valova, V.A.; Graham, M.E.; Robinson, P.J.; Bernard, O. The phosphorylation of p25/TPPP by LIM kinase 1 inhibits its ability to assemble microtubules. Exp. Cell Res. 2007, 313, 4091–4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardilovich, K.; Baugh, M.; Crighton, D.; Kowalczyk, D.; Gabrielsen, M.; Munro, J.; Croft, D.R.; Lourenco, F.; James, D.; Kalna, G.; et al. LIM kinase inhibitors disrupt mitotic microtubule organization and impair tumor cell proliferation. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 38469–38486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yi, F.; Guo, J.; Dabbagh, D.; Spear, M.; He, S.; Kehn-Hall, K.; Fontenot, J.; Yin, Y.; Bibian, M.; Park, C.M.; et al. Discovery of Novel Small-Molecule Inhibitors of LIM Domain Kinase for Inhibiting HIV-1. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e02418-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, Z.; Yin, X.; Ma, M.; Ge, H.; Lang, B.; Sun, H.; He, S.; Fu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yu, X.; et al. IP-10 Promotes Latent HIV Infection in Resting Memory CD4+ T Cells via LIMK-Cofilin Pathway. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 656663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, B.A.; Almstead, Z.Y.; Burgoon, H.; Gardyan, M.; Goodwin, N.C.; Healy, J.; Liu, Y.; Mabon, R.; Marinelli, B.; Samala, L.; et al. Discovery and Development of LX7101, a Dual LIM-Kinase and ROCK Inhibitor for the Treatment of Glaucoma. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, X.; He, G.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Kong, Y.; Xie, W.; Jia, Z.; Liu, W.-T.; Zhou, Z. Transient inhibition of LIMKs significantly attenuated central sensitization and delayed the development of chronic pain. Neuropharmacology 2017, 125, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romarowski, A.; Battistone, M.A.; La Spina, F.A.; Puga Molina, L.d.C.; Luque, G.M.; Vitale, A.M.; Cuasnicu, P.S.; Visconti, P.E.; Krapf, D.; Buffone, M.G. PKA-dependent phosphorylation of LIMK1 and Cofilin is essential for mouse sperm acrosomal exocytosis. Dev. Biol. 2015, 405, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Park, J.; Kim, S.W.; Cho, M.C. The Role of LIM Kinase in the Male Urogenital System. Cells 2022, 11, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrilli, A.; Copik, A.; Posadas, M.; Chang, L.S.; Welling, D.B.; Giovannini, M.; Fernández-Valle, C. LIM domain kinases as potential therapeutic targets for neurofibromatosis type 2. Oncogene 2014, 33, 3571–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Starinsky-Elbaz, S.; Faigenbloom, L.; Friedman, E.; Stein, R.; Kloog, Y. The pre-GAP-related domain of neurofibromin regulates cell migration through the LIM kinase/cofilin pathway. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2009, 42, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallée, B.; Doudeau, M.; Godin, F.; Gombault, A.; Tchalikian, A.; de Tauzia, M.-L.; Bénédetti, H. Nf1 RasGAP Inhibition of LIMK2 Mediates a New Cross-Talk between Ras and Rho Pathways. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cuberos, H.; Vallée, B.; Vourc’h, P.; Tastet, J.; Andres, C.R.; Bénédetti, H. Roles of LIM kinases in central nervous system function and dysfunction. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 3795–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ben Zablah, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gugustea, R.; Jia, Z. LIM-Kinases in Synaptic Plasticity, Memory, and Brain Diseases. Cells 2021, 10, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, D.; Preuss, F.; Dederer, V.; Knapp, S.; Mathea, S. Structural Aspects of LIMK Regulation and Pharmacology. Cells 2022, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamill, S.; Lou, H.J.; Turk, B.E.; Boggon, T.J. Structural Basis for Noncanonical Substrate Recognition of Cofilin/ADF Proteins by LIM Kinases. Mol. Cell 2016, 62, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salah, E.; Chatterjee, D.; Beltrami, A.; Tumber, A.; Preuss, F.; Canning, P.; Chaikuad, A.; Knaus, P.; Knapp, S.; Bullock, A.N.; et al. Lessons from LIMK1 enzymology and their impact on inhibitor design. Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 3197–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrobelski, S.T.; Lin, S.; Leftheris, K.; He, L.; Seitz, S.P.; Lin, T.-A.; Vaccaro, W. Phenyl-Substituted Pyrimidine Compounds Useful as Kinase Inhibitors. Patent WO 2006/084017 A2, 10 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ross-Macdonald, P.; de Silva, H.; Guo, Q.; Xiao, H.; Hung, C.-Y.; Penhallow, B.; Markwalder, J.; He, L.; Attar, R.M.; Lin, T.-A.; et al. Identification of a nonkinase target mediating cytotoxicity of novel kinase inhibitors. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 3490–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manetti, F. Recent Findings Confirm LIM Domain Kinases as Emerging Target Candidates for Cancer Therapy. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2012, 12, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manetti, F. Recent advances in the rational design and development of LIM kinase inhibitors are not enough to enter clinical trials. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 155, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, N.A.S.; Tandiary, A.M.; Al-Sanea, M.M.; Abdelgawad, A.M.; Chee, F.C.; Hussain, A.M. Small Molecules as LIM Kinase Inhibitors. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Seitz, S.P.; Trainor, G.L.; Tortolani, D.; Vaccaro, W.; Poss, M.; Tarby, C.M.; Tokarski, J.S.; Penhallow, B.; Hung, C.-Y.; et al. Modulation of cofilin phosphorylation by inhibition of the Lim family kinases. Biorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 5995–5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baell, J.B.; Street, I.P.; Sleebs, B.E. Pyrido [3′,2′:4,5]thieno [3,2-D]pyrimidin-4-ylamine Derivatives and Their Therapeutical Use. Patent WO 2012/131297 A1, 4 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sleebs, B.E.; Ganame, D.; Levit, A.; Street, I.P.; Gregg, A.; Falk, H.; Baell, J.B. Development of substituted 7-phenyl-4-aminobenzothieno[3,2-d] pyrimidines as potent LIMK1 inhibitors. MedChemComm 2011, 2, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleebs, B.E.; Levit, A.; Street, I.P.; Falk, H.; Hammonds, T.; Wong, A.C.; Charles, M.D.; Olson, M.F.; Baell, J.B. Identification of 3-aminothieno[2,3-b]pyridine-2-carboxamides and 4-aminobenzothieno[3,2-d]pyrimidines as LIMK1 inhibitors. MedChemComm 2011, 2, 977–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleebs, B.E.; Nikolakopoulos, G.; Street, I.P.; Falk, H.; Baell, J.B. Identification of 5,6-substituted 4-aminothieno[2,3-d]pyrimidines as LIMK1 inhibitors. Biorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 5992–5994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sleebs, B.E.; Street, I.P.; Bu, X.; Baell, J.B. De Novo Synthesis of a Potent LIMK1 Inhibitor. Synthesis 2010, 2010, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoon, H.; Goodwin, N.; Harrison, B.; Healy, J.; Liu, Y.; Mabon, R.; Marinelli, B.; Rawlins, D.; Rice, D.; Whitlock, N. LIMK Inhibitors, Compositions Comprising Them, and Methods of Their Use. Patent WO 2009/131940 A1, 29 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, B.A.; Whitlock, N.A.; Voronkov, M.V.; Almstead, Z.Y.; Gu, K.-j.; Mabon, R.; Gardyan, M.; Hamman, B.D.; Allen, J.; Gopinathan, S.; et al. Novel Class of LIM-Kinase 2 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Ocular Hypertension and Associated Glaucoma. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6515–6518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, S.; Bourin, A.; Alen, J.; Geraets, J.; Schroeders, P.; Castermans, K.; Kindt, N.; Boumans, N.; Panitti, L.; Vanormelingen, J.; et al. Design, synthesis and biological characterization of selective LIMK inhibitors. Biorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 4005–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourin, A.P.J.; Boland, S.; Defert, O. Lim Kinase Inhibitors. Patent WO 2015150337, 8 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

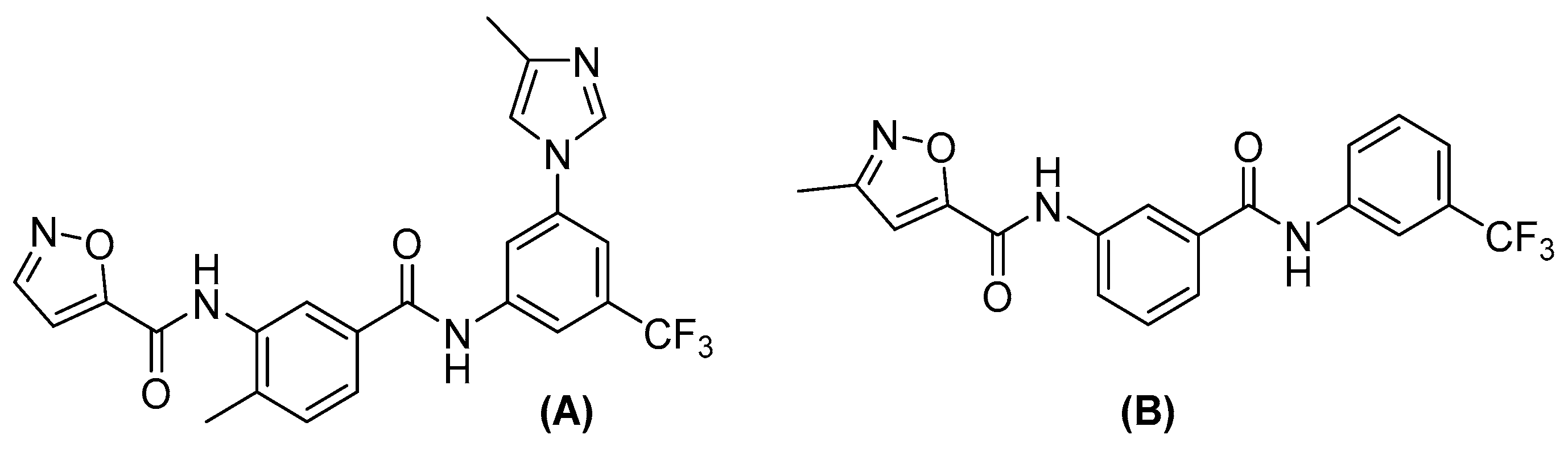

- Cui, J.; Ding, M.; Deng, W.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Sun, G.; Jiang, Y.; Feng, Y. Discovery of bis-aryl urea derivatives as potent and selective Limk inhibitors: Exploring Limk1 activity and Limk1/ROCK2 selectivity through a combined computational study. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 7464–7477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, N.C.; Cianchetta, G.; Burgoon, H.A.; Healy, J.; Mabon, R.; Strobel, E.D.; Allen, J.; Wang, S.; Hamman, B.D.; Rawlins, D.B. Discovery of a Type III Inhibitor of LIM Kinase 2 That Binds in a DFG-Out Conformation. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yin, Y.; Zheng, K.; Eid, N.; Howard, S.; Jeong, J.-H.; Yi, F.; Guo, J.; Park, C.M.; Bibian, M.; Wu, W.; et al. Bis-aryl Urea Derivatives as Potent and Selective LIM Kinase (Limk) Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 1846–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alen, J.; Bourin, A.; Boland, S.; Geraets, J.; Schroeders, P.; Defert, O. Tetrahydro-pyrimido-indoles as selective LIMK inhibitors: Synthesis, selectivity profiling and structure-activity studies. MedChemComm 2016, 7, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routier, S.; Bénédetti, H.; Vallée-Meheust, B.; Bonnet, P.; Plé, K.; Aci-Sèche, S.; Ruchaud, S.; Braka, A.; Champiré, A.; Andrès, C.; et al. 4-(7H-pyrrolo[2,3-D]pyrimidin-4-yl)-3,6-dihydropyridine-(2H)-carboxamide Derivatives as Limk and/or Rock Kinases Inhibitors for Use in the Treatment of Cancer. Patent WO 2021239727 A1, 2 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rybin, M.J.; Laverde-Paz, M.J.; Suter, R.K.; Affer, M.; Ayad, N.G.; Feng, Y.; Zeier, Z. A dual aurora and lim kinase inhibitor reduces glioblastoma proliferation and invasion. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 61, 128614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariawan, D.; Au, C.; Paric, E.; Fath, T.; Ke, Y.D.; Kassiou, M.; van Eersel, J.; Ittner, L.M. The Nature of Diamino Linker and Halogen Bonding Define Selectivity of Pyrrolopyrimidine-Based LIMK1 Inhibitors. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 781213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Doherty, J.; Antonipillai, J.; Chen, S.; Devlin, M.; Visser, K.; Baell, J.; Street, I.; Anderson, R.L.; Bernard, O. LIM kinase inhibition reduces breast cancer growth and invasiveness but systemic inhibition does not reduce metastasis in mice. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2013, 30, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, C.; de la Fuente, V.; tom Dieck, S.; Nassim-Assir, B.; Dalmay, T.; Bartnik, I.; Lunardi, P.; de Oliveira Alvares, L.; Schuman, E.M.; Letzkus, J.J.; et al. LIMK, Cofilin 1 and actin dynamics involvement in fear memory processing. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2020, 173, 107275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanihara, H.; Inatani, M.; Honjo, M.; Tokushige, H.; Azuma, J.; Araie, M. Intraocular Pressure–Lowering Effects and Safety of Topical Administration of a Selective ROCK Inhibitor, SNJ-1656, in Healthy Volunteers. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2008, 126, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvi, P.; Janostiak, R.; Chava, S.; Manrai, P.; Yoon, E.; Singh, K.; Harigopal, M.; Gupta, R.; Wajapeyee, N. LIMK2 promotes the metastatic progression of triple-negative breast cancer by activating SRPK1. Oncogenesis 2020, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Lin, L.; Ruiz, C.; Khan, S.; Cameron, M.D.; Grant, W.; Pocas, J.; Eid, N.; Park, H.; Schröter, T.; et al. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Urea Derivatives as Highly Potent and Selective Rho Kinase Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 3568–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Cameron, M.D.; Lin, L.; Khan, S.; Schröter, T.; Grant, W.; Pocas, J.; Chen, Y.T.; Schürer, S.; Pachori, A.; et al. Discovery of Potent and Selective Urea-Based ROCK Inhibitors and Their Effects on Intraocular Pressure in Rats. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Henderson, B.W.; Greathouse, K.M.; Ramdas, R.; Walker, C.K.; Rao, T.C.; Bach, S.V.; Curtis, K.A.; Day, J.J.; Mattheyses, A.L.; Herskowitz, J.H. Pharmacologic inhibition of LIMK1 provides dendritic spine resilience against beta-amyloid. Sci. Signal. 2019, 12, eaaw9318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, S.; Vernos, I. Microtubule assembly during mitosis—From distinct origins to distinct functions? J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 2805–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, J.; Giannakakou, P. Targeting Microtubules for Cancer Chemotherapy. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005, 5, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dumontet, C.; Jordan, M.A. Microtubule-binding agents: A dynamic field of cancer therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Čermák, V.; Dostál, V.; Jelínek, M.; Libusová, L.; Kovář, J.; Rösel, D.; Brábek, J. Microtubule-targeting agents and their impact on cancer treatment. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 99, 151075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudent, R.; Vassal-Stermann, E.; Nguyen, C.-H.; Pillet, C.; Martinez, A.; Prunier, C.; Barette, C.; Soleilhac, E.; Filhol, O.; Beghin, A.; et al. Pharmacological Inhibition of LIM Kinase Stabilizes Microtubules and Inhibits Neoplastic Growth. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 4429–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vassal, E.; Barette, C.; Fonrose, X.; Dupont, R.; Sans-Soleilhac, E.; Lafanechère, L. Miniaturization and Validation of a Sensitive Multiparametric Cell-Based Assay for the Concomitant Detection of Microtubule-Destabilizing and Microtubule-Stabilizing Agents. J. Biomol. Screen. 2006, 11, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rivalle, C.; Wendling, F.; Tambourin, P.; Lhoste, J.M.; Bisagni, E.; Chermann, J.C. Antitumor amino-substituted pyrido[3′,4′:4,5]pyrrolo[2,3-g]isoquinolines and pyrido[4,3-b]carbazole derivatives: Synthesis and evaluation of compounds resulting from new side chain and heterocycle modifications. J. Med. Chem. 1983, 26, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafanechere, L.; Vassal, E.; Barette, C.; Nguyen, C.H.; Rivalle, C.; Prudent, R. Pyridocarbazole Type Compounds and Applications Thereof. U.S. Patent 8604048 B2, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Prunier, C.; Kapur, R.; Lafanechère, L. Targeting LIM kinases in taxane resistant tumors. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 50816–50817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gory-Fauré, S.; Powell, R.; Jonckheere, J.; Lanté, F.; Denarier, E.; Peris, L.; Nguyen, C.H.; Buisson, A.; Lafanechère, L.; Andrieux, A. Pyr1-Mediated Pharmacological Inhibition of LIM Kinase Restores Synaptic Plasticity and Normal Behavior in a Mouse Model of Schizophrenia. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 627995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashiach Farkash, E.; Rak, R.; Elad-Sfadia, G.; Haklai, R.; Carmeli, S.; Kloog, Y.; Wolfson, H. Computer-Based Identification of a Novel LIMK1/2 Inhibitor that Synergizes with Salirasib to Destabilize the Actin Cytoskeleton. Oncotarget 2012, 3, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janes, P.W.; Slape, C.I.; Farnsworth, R.H.; Atapattu, L.; Scott, A.M.; Vail, M.E. EphA3 biology and cancer. Growth Factors 2014, 32, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Syeda, F.; Walker, J.R.; Finerty, P.J.; Cuerrier, D.; Wojciechowski, A.; Liu, Q.; Dhe-Paganon, S.; Gray, N.S. Discovery and structural analysis of Eph receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Biorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 4467–4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rak, R.; Haklai, R.; Elad-Tzfadia, G.; Wolfson, H.J.; Carmeli, S.; Kloog, Y. Novel LIMK2 Inhibitor Blocks Panc-1 Tumor Growth in a mouse xenograft model. Oncoscience 2014, 1, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demyanenko, S.V.; Uzdensky, A. LIM kinase inhibitor T56-LIMKi protects mouse brain from photothrombotic stroke. Brain Injury 2021, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faltynek, C.R.; Schroeder, J.; Mauvais, P.; Miller, D.; Wang, S.; Murphy, D.; Lehr, R.; Kelley, M.; Maycock, A. Damnacanthal Is a Highly Potent, Selective Inhibitor of p56lck Tyrosine Kinase Activity. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 12404–12410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, K.; Sampei, K.; Nakagawa, M.; Uchiumi, N.; Amanuma, T.; Aiba, S.; Oikawa, M.; Mizuno, K. Damnacanthal, an effective inhibitor of LIM-kinase, inhibits cell migration and invasion. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 828–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djamai, H.; Berrou, J.; Dupont, M.; Kaci, A.; Ehlert, J.E.; Weber, H.; Baruchel, A.; Paublant, F.; Prudent, R.; Gardin, C.; et al. Synergy of FLT3 inhibitors and the small molecule inhibitor of LIM kinase1/2 CEL_Amide in FLT3-ITD mutated Acute Myeloblastic Leukemia (AML) cells. Leuk. Res. 2021, 100, 106490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Pu, W.; Zheng, Q.; Ai, M.; Chen, S.; Peng, Y. Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) in cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Cai, M.; Shao, L.; Zhang, J. Targeting Protein Kinases Degradation by PROTACs. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 679120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, K.A.; Ferguson, F.M.; Bushman, J.W.; Eleuteri, N.A.; Bhunia, D.; Ryu, S.; Tan, L.; Shi, K.; Yue, H.; Liu, X.; et al. Mapping the Degradable Kinome Provides a Resource for Expedited Degrader Development. Cell 2020, 183, 1714–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compd | R | LIMK2 IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | H | 800 |

| 6 | 2-Me | 11,500 |

| 7 | 3-Me | 650 |

| 8 | 4-Me | 1300 |

| 9 | 3-OMe | 520 |

| 10 | 3-Oph | 64 |

| 11 | 3-Br | 300 |

| Compd | R | LIMK2 | LIMK1 | ROCK1 | ROCK2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (nM) a | ||||||

| 21 | Me (trans) | -- | 210 | -- | -- | -- |

| 22 | Me (cis) | -- | 110 | -- | -- | -- |

| 23 | -- | Allyl | 2.2 | -- | -- | -- |

| 24 | -- | OH | 138 | -- | -- | -- |

| 25 | -- | NMe2 | 5.1 | -- | -- | -- |

| 26 | -- | CH2CH2NMe2 | 7.3 | 134 | 139 | ND |

| LX7101 | -- | CH2NMe2 | 4.3 (7.5) | 32 (54) | 69 (2200) | 32 (340) |

| Molecule | Disease | Animal Model | Treatment Procedure | Observations and Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMS3 | Breast cancer | Balb/c or NSG mice with 4T1.2 cells injected into the mammary gland | - 20 control, 20 treated - 20 mg/kg in 10% DMSO/0.5% soln. in saline - IP daily for 30 days (day after cell injection) | - Still detectable in plasma 24 h after injection, half time of 5.6 h - Reduced level of phospho-cofilin - No effect on primary tumor growth - More numerous and larger tumor nodules in the lung | Li et al., 2013 [43] |

| Breast cancer | SCID mice with MDA-MB-23 cells injected into the mammary gland | - 5 control, 5 treated - 20 mg/kg in 10% DMSO/0.5% soln. in saline - IP daily for 29 days | - Reduced phospho-cofilin (60%) - Slight lag in tumor growth | Li et al., 2013 [43] | |

| BMS5-LIMKi3 | Memory reconsolidation | C57BL/6 male mice conditioned using a contextual fear paradigm, 24 h later were re-exposed to the training context for 5 min | - 10 mM (0.5 µL) bilateral injection in the hippocampus before the training session | - Memory reconsolidation impairment after context re-exposure | Medina et al., 2020 [44] |

| Chronic pain | C57BL/6 intraplantar injection of saline/CFA (complete Freund’s adjuvant) 1/1 | - 2, 5, and 10 µg intrathecal injection | - Alleviation of chronic pain development | Yang et al., 2017 [10] | |

| Lexicon | Glaucoma | Dexamethasone-induced ocular hypertensive mouse perfused pig eye | - 5 µL of 1 mg/mL xanthan gum suspension of compound - Infusion of 100 nM soln. at constant pressure | - Reduced increased intraocular pressure to normal level - Increased outflow capacities | Harrison et al., 2009 [33] |

| LX7101 | Glaucoma ocular hypertension | Dexamethasone-induced ocular hypertensive mouse clinical trial phase I | - 3 µL of 5 mg/mL HPMC based aqueous soln. | - 99% stability in an aqueous soln. after 14 days at 60 °C - Reduced increased of intraocular pressure | Harrison et al., 2015 [9] |

| LX7101 | Breast cancer | NSG mice injected with MDA-MB-231 | - 4 mice - 5 mg/kg in 0.5% methyl cellulose in PBS - Oral gavage for 4 weeks every other day 4 weeks after cell injection | - No inhibition of primary tumor growth - Reduced metastatic progression | Malvi et al., 2020 [46] |

| Compound 27 Amakem | Ocular hypertension | Ocular normotensive New Zealand White Rabbit | - 5 animals - 0.5% w/v soln. in PEG 400/water 1/1 - 40 µL eye drop (200 µg/eye drop) | - No significant reduction of intraocular pressure | Boland et al., 2015 [34] |

| SR11124 | Ocular hypertension | Old brown Norway rats initial elevated Intraocular Pressure (IOP) of 28 mm Hg | - 6 rats left eye control, right eye treated) - 50 µg applied once - Topical admin. | - Reduced intraocular pressure in rat eyes 4 h upon treatment | Yin et al., 2015 [38] |

| SR7826 | Alzheimer’s disease | hAPPJ20 mice | - 5 control, 5 treated - 10 mg/kg in 90% H2O/10% DMSO - Oral admin. daily for 11 days | - Rescued Aβ-induced hippocampal spine loss and morphological aberrations | Henderson et al., 2019 [49] |

| Pyr1 | Leukemia | B6D2F1 female mice were injected subcutaneously in the right flank with 2 × 106 L1210 cells | - 6 control, 6 treated - 10 mg/kg/d in PEG 400 - Intraperitoneally, on the left flank, daily for 10 days | - No apparent toxicity - 100% vehicle-treated mice dead at day 70 - 100% Pyr1-treated mice alive at day 90 => complete survival gain | Prudent et al., 2012 [54] |

| Breast cancer | NMRI nude mice with TS/A-pGL3 cells stably transfected with luciferase injected into the mammary fat pad | - 10 control, 10 treated - 10 mg/kg in 36% PEG 400, 10% DMSO, 54% NaCl 0.9% - IP daily for 14 days (7 days after cell injection) | - Tumor followed by bioluminescence - Pyr1 metabolization into 9-OH metabolite M1, which disappeared within 2 h - In the tumor: acetyl and detyrosinated tubulin increase, phospho-cofilin unaffected - Pyr1 stopped tumor growth | Prunier et al., 2016 [58] | |

| Breast cancer | NMRI nude mice with MDA-MB-231 injected into the right flank | - 10 control, 10 treated - 10 mg/kg in 36% PEG 400, 10% DMSO, 54% NaCl 0.9% - IP daily for 7 days (21 days after cell injection) | In the tumor: significant decrease in volume, reduced cellular density, acetyl and detyrosinated tubulin increase, phospho-cofilin unaffected | Prunier et al., 2016 [58] | |

| Breast cancer | NSG female injected in the mammary fat pad with MDA-MB-231 Dendra2 | - 3 control, 4 treated - 10 mg/kg in 36% PEG 400, 10% DMSO, 54% NaCl 0.9% - IP daily for 14 days (30 to 45 after cell injection) | - In the tumor: cells were rounder and less packed, cell proliferation was decreased, apoptotic cells were more numerous - Rounder cells had higher velocity compared to elongated ones - No effect on the number of lung metastases, but sizes were reduced | Prunier et al., 2016 [58] | |

| Breast cancer | NMRI nude mice with MDA-MB-231-ZNF217rvLuc2 stably transfected with luciferase injected into the left ventricle | - 9 control, 15 treated - 10 mg/kg in 36% PEG 400, 10% DMSO, 54% NaCl 0.9%—IP daily for 35 days (3 days before cell injection) | - No effect on the number of metastases - Strong reduction of metastatic growth | Prunier et al., 2016 [58] | |

| Schizophrenia | C57BL6/129SvPas-F1 MAP6 KO male mice | - 100 mg/kg/week in 0.43% NaCl, 32% PEG 400 - IP twice a week for at least 6 weeks | - Restored normal dendritic spine density - Improved long-term potentiation - Improved long-term synaptic plasticity - Reduced social withdrawal and depressive/anxiety-like behavior | Gory-Fauré et al., 2021 [59] | |

| T56-LIMKi | Pancreatic cancer | Nude CD1-Nu mice injected with 5 × 106 Panc-1 cells | - 8 control, 8 treated - 30 or 60 mg/kg in 0.5% CarboxyMethylCellulose: CMC - Oral admin. daily for 22 days (7 days after cell injection) | - No toxicity up to 100 mg/kg - Dose- and time-dependent decrease in tumor volume with a stronger effect for the 60 mg/kg dose. For 50% of the animals, tumor completely disappeared upon 35 day treatment - 25% decrease of phospho-cofiline for the dose 60 mg/kg | Rak et al., 2014 [63] |

| T56-LIMKi | Photothrombotic stroke | CD-1 mice 14–15 weeks photothrombotic stroke (PTS) | - 30 mg/kg in 0.5% CMC - Oral admin. daily for 5 days after PTS. 1st admin. 1 h upon PTS | - Reduction of the infarction volume by 2 or 3.4 times at 7 or 14 days after PTS - Rescued morphological changes in the brain - Reduced number of pathologically altered cells - Increased number of normochromic neurons | Demyanenko and Uzdensky 2021 [64] |

| Damnacanthal | Cutaneous immune response | BALB/c mice; ears painted with 2,4,6-trinitrochlorobenzene (TNCB) | - 20 µM 30 min. before TNCB treatment, immediately after and 12 h later - Topical admin. | - Suppressed hapten-induced migration of Langerhans cells in ears | Ohashi et al., 2014 [66] |

| CEL-Amide | Acute Myeloblastic Leukemia | FLT3-ITD+ NOD-SCID mice injected intravenously with MOLM-13-LUC | - 10 control, 10 treated - 10 mg/kg in 0.15 M NaCl - Oral admin. until death (11 days upon cell injection) | - Delay of MOLM-13-LUC engraftment for the combination of CEL-Amide and midostaurin | Djamai et al., 2021 [67] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berabez, R.; Routier, S.; Bénédetti, H.; Plé, K.; Vallée, B. LIM Kinases, Promising but Reluctant Therapeutic Targets: Chemistry and Preclinical Validation In Vivo. Cells 2022, 11, 2090. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11132090

Berabez R, Routier S, Bénédetti H, Plé K, Vallée B. LIM Kinases, Promising but Reluctant Therapeutic Targets: Chemistry and Preclinical Validation In Vivo. Cells. 2022; 11(13):2090. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11132090

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerabez, Rayan, Sylvain Routier, Hélène Bénédetti, Karen Plé, and Béatrice Vallée. 2022. "LIM Kinases, Promising but Reluctant Therapeutic Targets: Chemistry and Preclinical Validation In Vivo" Cells 11, no. 13: 2090. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11132090