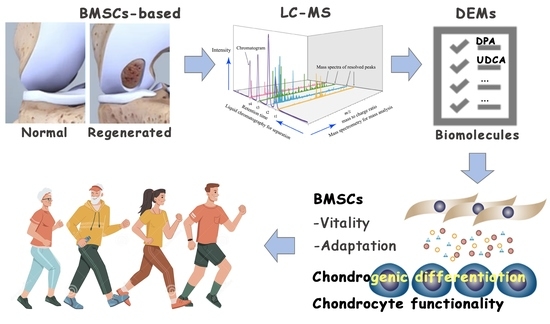

Cartilaginous Metabolomics Reveals the Biochemical-Niche Fate Control of Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rabbit Microfracture Model

2.2. Tissue Collection

2.3. Histochemistry

2.4. Metabolomics

2.4.1. Sample Preparation for Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry

2.4.2. Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry

2.4.3. Bioinformatics Data Processing

2.4.4. Identification of the Differentially Expressed Metabolites

2.4.5. Pathway Enrichment Analysis

2.5. Cell Culture and Differentiation Induction

2.5.1. Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cell Culture

2.5.2. Chondrogenic Differentiation

2.6. Stimuli and Chemicals Administrated

2.7. Cell Vitality

2.8. Immunofluorescence

2.9. Real-Time PCR

3. Results

3.1. The Histomorphologic Changes in the Regenerated Cartilage

3.2. The Metabolomic Changes in the Regenerated Cartilage

3.3. Differentially Expressed Metabolites Involved in Promoting the Vitality and Adaptation of BMSCs

3.4. Differentially Expressed Metabolites Involved in Promoting Chondrogenic Differentiation

3.5. Differentially Expressed Metabolites Involved in Promoting Chondrocyte Functionality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roseti, L.; Desando, G.; Cavallo, C.; Petretta, M.; Grigolo, B. Articular Cartilage Regeneration in Osteoarthritis. Cells 2019, 8, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, T.S.; Yee, Y.M.; Khan, I.M. Chondrocyte Aging: The Molecular Determinants and Therapeutic Opportunities. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 625497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andia, I.; Maffulli, N. Biological Therapies in Regenerative Sports Medicine. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 807–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Mackay, A.M.; Beck, S.C.; Jaiswal, R.K.; Douglas, R.; Mosca, J.D.; Moorman, M.A.; Simonetti, D.W.; Craig, S.; Marshak, D.R. Multilineage Potential of Adult Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Science 1999, 284, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, G.-I. Endogenous Cartilage Repair by Recruitment of Stem Cells. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2016, 22, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, J.R.; Briggs, K.K.; Rodrigo, J.J.; Kocher, M.S.; Gill, T.J.; Rodkey, W.G. Outcomes of microfracture for traumatic chondral defects of the knee: Average 11-year follow-up. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2003, 19, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Kim, B.-S.; Lee, H.; Im, G.-I. In Vivo Tracking of Mesechymal Stem Cells Using Fluorescent Nanoparticles in an Osteochondral Repair Model. Mol. Ther. 2012, 20, 1434–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armiento, A.R.; Alini, M.; Stoddart, M.J. Articular fibrocartilage—Why does hyaline cartilage fail to repair? Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 146, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, S.J.; Spradling, A.C. Stem Cells and Niches: Mechanisms That Promote Stem Cell Maintenance throughout Life. Cell 2008, 132, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Lee, Y.D.; Wagers, A.J. Stem cell aging: Mechanisms, regulators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ward, O.P.; Singh, A. Omega-3/6 fatty acids: Alternative sources of production. Process Biochem. 2005, 40, 3627–3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.Y.; Ryu, J.M.; Lee, S.H.; Park, J.H.; Han, H.J. Lipid rafts play an important role for maintenance of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 2082–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.K. Control of Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Senescence by Tryptophan Metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denu, R.A.; Hematti, P. Effects of Oxidative Stress on Mesenchymal Stem Cell Biology. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 2989076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Hirao, A.; Arai, F.; Matsuoka, S.; Takubo, K.; Hamaguchi, I.; Nomiyama, K.; Hosokawa, K.; Sakurada, K.; Nakagata, N.; et al. Regulation of oxidative stress by ATM is required for self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 2004, 431, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Shi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yang, J. The replicative senescent mesenchymal stem/stromal cells defect in DNA damage response and anti-oxidative capacity. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 15, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepetsos, P.; Papavassiliou, A.G. ROS/oxidative stress signaling in osteoarthritis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Basis Dis. 2016, 1862, 576–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, Z.; Longman, A.; Hurst, S.; Duggan, K.; Caterson, B.; Hughes, C.; Harwood, J. Relative efficacies of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in reducing expression of key proteins in a model system for studying osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2009, 17, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chevrier, A.; Hoemann, C.; Sun, J.; Lascau-Coman, V.; Buschmann, M. Bone marrow stimulation induces greater chondrogenesis in trochlear vs condylar cartilage defects in skeletally mature rabbits. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2013, 21, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, Y.; Mu, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, S.-T.; Yan, H.-J. Icariin alleviates osteoarthritis by inhibiting NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2019, 14, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorp, H.; Kim, K.; Kondo, M.; Grainger, D.W.; Okano, T. Fabrication of hyaline-like cartilage constructs using mesenchymal stem cell sheets. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Cheng, J.; Li, Y.; Ni, G. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry-Based Plasma Metabolomics Study of the Effects of Moxibustion with Seed-Sized Moxa Cone on Hyperlipidemia. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 1231357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhl, T.; Beier, J.P. Quantification of chondrogenic differentiation in monolayer cultures of mesenchymal stromal cells. Anal. Biochem. 2019, 582, 113356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremers, N.A.J.; Lundvig, D.M.S.; Van Dalen, S.C.M.; Schelbergen, R.F.; Van Lent, P.L.E.M.; Szarek, W.A.; Regan, R.F.; Carels, C.E.; Wagener, F.A.D.T.G. Curcumin-Induced Heme Oxygenase-1 Expression Prevents H2O2-Induced Cell Death in Wild Type and Heme Oxygenase-2 Knockout Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 17974–17999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.-Y.; Seo, J.; Huang, B.T.; Napolitano, T.; Champeil, E. Mitomycin C and decarbamoyl mitomycin C induce p53-independent p21WAF1/CIP1 activation. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 49, 1815–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Kuang, S.; Applegate, T.J.; Lin, T.-L.; Cheng, H.-W. Prenatal Serotonin Fluctuation Affects Serotoninergic Development and Related Neural Circuits in Chicken Embryos. Neuroscience 2021, 473, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, I.; Takeshita, N.; Yoshida, M.; Seki, D.; Oyanagi, T.; Kimura, S.; Jiang, W.; Sasaki, K.; Sogi, C.; Kawatsu, M.; et al. Ten-m/Odz3 regulates migration and differentiation of chondrogenic ATDC5 cells via RhoA-mediated actin reorganization. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 236, 2906–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, I.; Ikegawa, S. SOX9-dependent and -independent Transcriptional Regulation of Human Cartilage Link Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 50942–50948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerosch, J. Effects of Glucosamine and Chondroitin Sulfate on Cartilage Metabolism in OA: Outlook on Other Nutrient Partners Especially Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Int. J. Rheumatol. 2011, 2011, 969012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parate, D.; Kadir, N.D.; Celik, C.; Lee, E.H.; Hui, J.H.P.; Franco-Obregón, A.; Yang, Z. Pulsed electromagnetic fields potentiate the paracrine function of mesenchymal stem cells for cartilage regeneration. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadet, J.; Wagner, J.R. DNA Base Damage by Reactive Oxygen Species, Oxidizing Agents, and UV Radiation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a012559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Esdaille, C.J.; Bhattacharjee, M.; Kan, H.-M.; Laurencin, C.T. The synthetic artificial stem cell (SASC): Shifting the paradigm of cell therapy in regenerative engineering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2116865118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M. Citric acid cycle and role of its intermediates in metabolism. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 68, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeske, S.S.; Theodoraki, M.N.; Boelke, E.; Laban, S.; Brunner, C.; Rotter, N.; Jackson, E.K.; Hoffmann, T.K.; Schuler, P.J. Adenosine production in mesenchymal stromal cells in relation to their developmental status. HNO 2020, 68, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamante, L.; Martello, G. Metabolic regulation in pluripotent stem cells. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2022, 75, 101923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, S.; Milstien, S. Functions of the Multifaceted Family of Sphingosine Kinases and Some Close Relatives. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 2125–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Subbarao, R.B.; Rho, G.J. Human mesenchymal stem cells—Current trends and future prospective. Biosci. Rep. 2015, 35, e00191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalvilla, A.; Gómez, R.; Largo, R.; Herrero-Beaumont, G. Lipid Transport and Metabolism in Healthy and Osteoarthritic Cartilage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 20793–20808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, D.A.; Yaspelkis, B.B., III.; Hawley, J.A.; Lessard, S.J. Lipid-induced mTOR activation in rat skeletal muscle reversed by exercise and 5′-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-d-ribofuranoside. J. Endocrinol. 2009, 202, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, H.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, W.; He, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, H.; Lin, J.; Chen, Y.; Xing, D.; et al. Targeted cell therapy for partial-thickness cartilage defects using membrane modified mesenchymal stem cells by transglutaminase 2. Biomaterials 2021, 275, 120994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielson, B.T.; Knudson, C.B.; Knudson, W. Extracellular Processing of the Cartilage Proteoglycan Aggregate and Its Effect on CD44-mediated Internalization of Hyaluronan. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 9555–9570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentili, C.; Tutolo, G.; Pianezzi, A.; Cancedda, R.; Cancedda, F.D. Cholesterol secretion and homeostasis in chondrocytes: A liver X receptor and retinoid X receptor heterodimer mediates apolipoprotein A1 expression. Matrix Biol. 2005, 24, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primer |

|---|---|

| SOX9 | F: TAAGCTAAAGGCAACTCGTACC |

| R: TAGAGAATATTCCTCACAGAGGACT | |

| ACAN | F: TGAGCGGCAGCACTTTGAC |

| R: TGAGTACAGGAGGCTTGAGG | |

| COL2A1 | F: TCCAGATGACCTTCCTACGC |

| R: GGTATGTTTCGTGCAGCCAT | |

| β-actin | F: CCCTGGAGAAGAGCTACGAG |

| R: CGTACAGGTCTTTGCGGATG |

| Category | Metabolite | m/za | RT b (min) | Error c (ppm) | VIP d | p-Value e | FC f | Trend | Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipids and lipid-like molecules (47) | (7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z)-docosatetraenoate | 333.2783 | 13.8609 | −2.0938 | 2.0825 | 0.0247 | 2.0327 | up | C22H36O2 |

| Arachidonic acid | 305.2472 | 13.0585 | −1.1653 | 5.4988 | 0.0064 | 1.8881 | up | C20H32O2 | |

| Fludrocortisone acetate | 405.2081 | 1.5828 | 2.2102 | 1.1184 | 0.0280 | 3.0242 | up | C23H31FO6 | |

| L-Palmitoylcarnitine | 400.3419 | 10.9240 | −0.6476 | 2.5445 | 0.0051 | 2.4512 | up | C23H45NO4 | |

| LysoPC(18:1(11Z)) | 522.3545 | 11.1461 | −1.7806 | 2.8324 | 0.0022 | 1.6622 | up | C26H52NO7P | |

| LysoPC(20:4(8Z,11Z,14Z,17Z)) | 544.3386 | 10.7015 | −2.1933 | 4.1157 | 0.0028 | 2.7755 | up | C28H50NO7P | |

| LysoPC(22:5(7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z,19Z)) | 570.3543 | 10.8646 | −1.8896 | 1.1338 | 0.0039 | 5.7136 | up | C30H52NO7P | |

| Prostaglandin E2 | 351.2173 | 8.2029 | −1.5090 | 1.6011 | 0.0441 | 6.5508 | up | C20H32O5 | |

| SM(d18:1/24:1(15Z)) | 813.6829 | 13.1903 | −1.8179 | 9.4552 | 0.0485 | 9.0986 | up | C47H93N2O6P | |

| Sphingosine | 282.2784 | 10.4050 | −2.4257 | 1.4741 | 0.0028 | 1.8594 | up | C18H37NO2 | |

| DPA | 331.2630 | 13.2346 | −0.4486 | 1.2545 | 0.0349 | 5.5002 | up | C22H34O2 | |

| Oleamide | 304.2607 | 13.1326 | −1.4413 | 2.3222 | 0.0257 | 1.6991 | up | C18H35NO | |

| Ursodeoxycholic acid | 391.2857 | 10.7032 | 0.8484 | 1.0112 | 0.0472 | 12.4921 | up | C24H40O4 | |

| PI(O-18:0/0:0) | 604.3833 | 14.9395 | −1.7930 | 3.2441 | 0.0000 | 0.6783 | down | C34H50O8 | |

| LysoPE(0:0/20:4(8Z,11Z,14Z,17Z)) | 502.2918 | 10.6718 | −2.0758 | 7.3932 | 0.0004 | 1.7392 | up | C25H44NO7P | |

| 6-[3]-ladderane-1-hexanol | 280.2635 | 12.3763 | −1.9348 | 6.3252 | 0.0251 | 1.7063 | up | C18H30O | |

| PS(14:0/24:1(15Z)) | 840.5728 | 11.4733 | 0.3863 | 1.6386 | 0.0196 | 14.4043 | up | C44H84NO10P | |

| LysoPE(22:4(7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z)/0:0) | 530.3229 | 11.2206 | −2.3436 | 4.2432 | 0.0010 | 1.7410 | up | C27H48NO7P | |

| PS(14:1(9Z)/24:0) | 840.5734 | 12.8225 | 1.0620 | 3.3834 | 0.0114 | 53.3843 | up | C44H84NO10P | |

| Linoelaidic Acid | 263.2365 | 13.2051 | −1.6593 | 3.3825 | 0.0354 | 1.6614 | up | C18H32O2 | |

| Pelargonidin 3-(6″-p-coumarylglucoside)-5-(6‴-acetylglucoside) | 763.1887 | 0.9317 | 0.9657 | 1.7822 | 0.0417 | 0.4288 | down | C38H38O18 | |

| PC(O-16:0/0:0) | 482.3591 | 11.3248 | −2.8591 | 2.1609 | 0.0008 | 2.6328 | up | C24H52NO6P | |

| LysoPC(18:2(9Z,12Z)) | 520.3395 | 10.6718 | −0.4349 | 2.1558 | 0.0049 | 2.6192 | up | C26H50NO7P | |

| LysoPE(0:0/18:2(9Z,12Z)) | 476.2778 | 10.6394 | −1.0077 | 1.3499 | 0.0031 | 3.4070 | up | C23H44NO7P | |

| LysoPE(22:5(7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z,19Z)/0:0) | 528.3073 | 10.8350 | −2.1896 | 2.5262 | 0.0015 | 4.1787 | up | C27H46NO7P | |

| 1-O-(2R-hydroxy-hexadecyl)-sn-glycerol | 355.2815 | 12.7332 | −2.7314 | 2.4189 | 0.0170 | 0.8881 | down | C19H40O4 | |

| 2,3,4,5,2′,3′,4′,6′-Octamethoxychalcone | 895.3420 | 0.7166 | 2.9042 | 1.6332 | 0.0189 | 0.7754 | down | C23H28O9 | |

| 15-hydroxy-tetracosa-6,9,12,16,18-pentaenoic acid | 357.2786 | 10.7015 | −0.4361 | 1.5497 | 0.0168 | 4.0203 | up | C24H38O3 | |

| Xestoaminol C | 230.2473 | 9.4959 | −2.5076 | 1.9590 | 0.0078 | 1.4550 | up | C14H31NO | |

| LysoPE(18:2(9Z,12Z)/0:0) | 478.2919 | 10.6421 | −1.8674 | 1.8550 | 0.0005 | 2.6353 | up | C23H44NO7P | |

| 1,2-(8R,9R-epoxy-17E-octadecen-4,6-diynoyl)-3-(hexadecanoyl)sn-glycerol | 839.5820 | 11.9032 | −0.0844 | 1.4486 | 0.0101 | 3.2667 | up | C54H80O8 | |

| 1-(11Z,14Z-eicosadienoyl)-glycero-3-phosphate | 507.2730 | 11.5926 | 0.2704 | 1.2619 | 0.0014 | 4.1891 | up | C23H43O7P | |

| Stearoylcarnitine | 428.3724 | 11.4139 | −2.4569 | 1.5537 | 0.0045 | 4.1705 | up | C25H49NO4 | |

| 1-O-(2R-hydroxy-tetradecyl)-sn-glycerol | 327.2499 | 11.9180 | −3.8832 | 1.1413 | 0.0050 | 0.8497 | down | C17H36O4 | |

| LysoPE(0:0/22:5(7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z,19Z)) | 528.3073 | 11.0426 | −2.2949 | 1.3834 | 0.0059 | 2.6454 | up | C27H46NO7P | |

| 1-(2-methoxy-eicosanyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine | 508.3751 | 11.5454 | −2.0199 | 1.5825 | 0.0022 | 2.4697 | up | C26H56NO7P | |

| PC(0:0/18:1(9Z)) | 566.3471 | 11.1411 | 1.5304 | 1.5653 | 0.0258 | 2.0328 | up | C26H52NO7P | |

| N-(3-oxo-butanoyl)-homoserine lactone | 186.0753 | 0.9084 | −4.0254 | 1.1941 | 0.0065 | 1.7216 | up | C8H11NO4 | |

| PS(17:0/0:0) | 512.2973 | 11.6489 | −1.9114 | 1.0334 | 0.0236 | 0.2002 | down | C23H46NO9P | |

| Oleoylcarnitine | 426.3569 | 11.0426 | −2.1469 | 1.1955 | 0.0417 | 1.4961 | up | C25H47NO4 | |

| Linoleamide | 302.2448 | 12.3763 | −2.2846 | 1.0171 | 0.0368 | 1.6485 | up | C18H33NO | |

| 1-Arachidonoylglycerophosphoinositol | 603.2915 | 10.9093 | −2.2292 | 1.1105 | 0.0037 | 3.4729 | up | C29H49O12P | |

| Dodecanoylcarnitine | 344.2790 | 9.7305 | −1.6266 | 1.3234 | 0.0324 | 0.2012 | down | C19H37NO4 | |

| 1-(2-methoxy-13-methyl-tetradecanyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine | 522.2814 | 10.7905 | 2.3016 | 1.1583 | 0.0050 | 1.7855 | up | C22H46NO9P | |

| Europinidin | 330.0742 | 4.4330 | −1.1294 | 1.1275 | 0.0143 | 1.8673 | up | C16H13O5+ | |

| LysoPC(P-16:0) | 480.3432 | 11.3099 | −3.5157 | 1.5174 | 0.0234 | 1.8926 | up | C24H50NO6P | |

| (E)-2-Penten-1-ol | 104.1067 | 0.7885 | −3.0443 | 2.9246 | 0.0097 | 1.3086 | up | C5H10O | |

| Organic oxygen compounds (16) | D-Myoinositol 4-phosphate | 259.0220 | 0.7671 | −1.6433 | 2.6807 | 0.0147 | 0.1456 | down | C6H13O9P |

| N-Acetylgalactosamine | 244.0790 | 0.8485 | −0.5407 | 1.0594 | 0.0236 | 1.7493 | up | C8H15NO6 | |

| D-glycero-L-galacto-Octulose | 279.0470 | 0.7739 | −2.7275 | 1.2166 | 0.0385 | 0.6264 | down | C8H16O8 | |

| Pelargonidin | 272.0673 | 4.4259 | −2.2420 | 2.8195 | 0.0058 | 0.4624 | down | C15H11O5+ | |

| Malvidin | 332.0888 | 4.4543 | 1.6129 | 3.5305 | 0.0099 | 2.1895 | up | C17H15O7+ | |

| Cellotetraose | 684.2545 | 0.9383 | −1.7043 | 3.2822 | 0.0375 | 0.4180 | down | C24H42O21 | |

| N-Acetylgalactosaminyl lactose | 546.2017 | 0.9232 | −2.0868 | 2.2153 | 0.0058 | 0.4044 | down | C20H35NO16 | |

| Isopropyl β-D-ThiogalactoPyranoside | 221.0837 | 2.0908 | −1.9212 | 4.9497 | 0.0033 | 0.8273 | down | C9H18O5S | |

| 3,5-dihydroxy-4-(sulfooxy)benzoic acid | 250.9848 | 0.8485 | −3.1660 | 1.6067 | 0.0008 | 1.7730 | up | C7H6O8S | |

| 1,2,3,4-Tetramethoxy-5-(2-propenyl)benzene | 261.1095 | 8.1917 | −0.7636 | 2.3229 | 0.0175 | 0.8684 | down | C13H18O4 | |

| Vicianose | 295.1024 | 2.0365 | 0.1620 | 1.6166 | 0.0289 | 0.8576 | down | C11H20O10 | |

| 2-Deoxy-D-ribose 1,5-bisphosphate | 292.9836 | 8.1902 | 1.0583 | 1.3599 | 0.0082 | 0.7965 | down | C5H12O10P2 | |

| Lacto-N-triaose | 590.1927 | 0.9317 | −2.5947 | 1.0686 | 0.0309 | 0.3734 | down | C20H35NO16 | |

| 2-(5,8-Tetradecadienyl)cyclobutanone | 245.2258 | 13.2051 | −2.3519 | 1.1487 | 0.0368 | 1.7212 | up | C18H30O | |

| 4-Acetylzearalenone | 361.1658 | 13.0585 | 3.5409 | 1.1157 | 0.0164 | 1.8800 | up | C20H24O6 | |

| Myrigalone H | 304.1544 | 11.4883 | 0.2525 | 1.0970 | 0.0436 | 1.7111 | up | C17H18O4 | |

| Organic acids and derivatives (12) | L-Arginine | 175.1181 | 0.7447 | −4.9509 | 1.1077 | 0.0232 | 1.4089 | up | C6H14N4O2 |

| L-Phenylalanine | 166.0856 | 3.5249 | −4.1785 | 2.1999 | 0.0140 | 1.7636 | up | C9H11NO2 | |

| L-Tryptophan | 203.0824 | 4.3576 | −1.1300 | 1.1625 | 0.0066 | 1.8097 | up | C11H12N2O2 | |

| L-Tyrosine | 180.0665 | 2.2998 | −0.8408 | 1.9941 | 0.0065 | 1.7151 | up | C9H11NO3 | |

| 7,8-diaminononanoic acid | 171.1484 | 6.5341 | −4.3633 | 1.8274 | 0.0198 | 0.7210 | down | C9H20N2O2 | |

| Dopaxanthin | 779.2082 | 0.9317 | 3.6779 | 1.0294 | 0.0464 | 0.4276 | down | C18H18N2O8 | |

| 6-(5-carboxy-2-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenoxy)-3,4,5-trihydroxyoxane-2-carboxylic acid | 361.0779 | 0.9383 | 3.8961 | 1.3373 | 0.0374 | 0.5079 | down | C14H16O11 | |

| S-Glutathionyl-L-cysteine | 427.0942 | 0.9232 | −2.2858 | 1.7851 | 0.0390 | 4.6303 | up | C13H22N4O8S2 | |

| Cysteineglutathione disulfide | 425.0798 | 0.9189 | −2.0096 | 1.7524 | 0.0369 | 4.9326 | up | C13H22N4O8S2 | |

| Propanoyl phosphate | 306.9978 | 9.7584 | −3.7713 | 1.3013 | 0.0154 | 0.7428 | down | C3H7O5P | |

| 2-Hydroxycinnamic acid | 182.0804 | 2.3357 | −4.7335 | 2.6129 | 0.0184 | 1.9098 | up | C9H8O3 | |

| Hydroxymethylphosphonate | 110.9848 | 0.8047 | −3.7569 | 1.1112 | 0.0311 | 1.5147 | up | CH5O4P | |

| Heterocyclic Compounds (15) | Uracil | 113.0342 | 1.2618 | −3.2771 | 1.4253 | 0.0280 | 1.7119 | up | C4H4N2O2 |

| Deethylatrazine | 188.0701 | 4.3813 | −0.5980 | 2.6772 | 0.0062 | 2.5574 | up | C6H10ClN5 | |

| dirithromycin | 563.5503 | 13.1326 | −4.2918 | 3.0670 | 0.0497 | 2.1749 | up | C39H72 | |

| 2′-O-Methyladenosine | 282.1185 | 3.3656 | −4.2975 | 1.1541 | 0.0233 | 0.3554 | down | C11H15N5O4 | |

| FAPy-adenine | 171.0985 | 14.2547 | −2.7181 | 10.0091 | 0.0045 | 0.7720 | down | C5H7N5O | |

| Pectachol | 460.2687 | 10.2578 | −1.3892 | 3.0608 | 0.0237 | 0.8238 | down | C26H34O6 | |

| 1-(1,2,3,4,5-Pentahydroxypent-1-yl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-beta-carboline-3-carboxylate | 367.1491 | 3.3656 | −2.4233 | 1.6882 | 0.0314 | 0.4717 | down | C17H22N2O7 | |

| Nocodazole | 300.0449 | 0.8047 | 0.1909 | 1.7345 | 0.0100 | 0.4874 | down | C14H11N3O3S | |

| Dipyridamole | 527.3043 | 12.0652 | 1.5729 | 1.2210 | 0.0388 | 0.8693 | down | C20H39N5O10 | |

| 6-Methyltetrahydropterin | 204.0861 | 0.9084 | 2.7681 | 1.2488 | 0.0079 | 1.8114 | up | C7H11N5O | |

| Gravacridonetriol | 396.0855 | 0.0425 | 3.1419 | 1.5097 | 0.0248 | 0.8872 | down | C19H19NO6 | |

| Nicorandil | 256.0578 | 0.9062 | 1.3308 | 1.0936 | 0.0068 | 2.2259 | up | C8H9N3O4 | |

| Ethosuximide M5 | 200.0562 | 2.2873 | −1.8422 | 1.1403 | 0.0168 | 1.9016 | up | C7H9NO3 | |

| Dihydrofolic acid | 424.1355 | 2.2873 | −4.4941 | 1.2621 | 0.0016 | 3.0187 | up | C19H21N7O6 | |

| AFN911 | 550.2322 | 0.9232 | −1.0333 | 1.0043 | 0.0310 | 0.5018 | down | C29H33N7O2 | |

| Organosulfur compounds (2) | Ethyl isopropyl disulfide | 137.0456 | 1.4293 | 1.9879 | 5.5947 | 0.0027 | 1.5142 | up | C5H12S2 |

| Ethyl propyl disulfide | 135.0312 | 1.4392 | 3.3806 | 2.2132 | 0.0018 | 1.3007 | up | C5H12S2 | |

| Hydrocarbons and derivatives (4) | 2-(Fluoromethoxy)-1,1,3,3,3-pentafluoro-1-propene (Compound A) | 358.9943 | 8.0025 | −1.1090 | 2.5442 | 0.0177 | 0.7840 | down | C4H2F6O |

| (+/−)-N,N-Dimethyl menthyl succinamide | 186.2209 | 14.2250 | −4.3869 | 2.2373 | 0.0327 | 0.8893 | down | C12H24 | |

| 2-Hexylidenecyclopentanone | 331.2642 | 13.8606 | −0.0544 | 1.2698 | 0.0331 | 2.6671 | up | C11H18O | |

| Aluminium dodecanoate | 663.4544 | 14.9840 | 0.4274 | 1.1638 | 0.0042 | 1.1576 | up | C36H69AlO6 |

| NO. | Annotation | p-Value a | Match Status b | Rich Factor c | Matching IDs | DEMs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Amoebiasis | 0.0000 | 4/13 | 0.3077 | C00062 C00219 C00584 C01074 | L-Arginine, Arachidonic acid, Prostaglandin E2, N-Acetylgalactosamine |

| 2 | Necroptosis | 0.0000 | 3/9 | 0.3333 | C00219 C00319 C00550 | Arachidonic acid, Sphingosine, SM(d18:1/24:1(15Z)) |

| 3 | Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis | 0.0001 | 4/52 | 0.0769 | C00062 C00078 C00079 C00082 | L-Arginine, L-Tryptophan, L-Phenylalanine, L-Tyrosine |

| 4 | Leishmaniasis | 0.0004 | 2/6 | 0.3333 | C00219 C00584 | Arachidonic acid, Prostaglandin E2 |

| 5 | Phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis | 0.0006 | 3/34 | 0.0882 | C00078 C00079 C00082 | L-Tryptophan, L-Phenylalanine, L-Tyrosine |

| 6 | African trypanosomiasis | 0.0007 | 2/8 | 0.2500 | C00078 C00584 | L-Tryptophan, Prostaglandin E2 |

| 7 | Oxytocin signaling pathway | 0.0017 | 2/12 | 0.1667 | C00219 C00584 | Arachidonic acid, Prostaglandin E2 |

| 8 | Regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes | 0.0023 | 2/14 | 0.1429 | C00219 C00584 | Arachidonic acid, Prostaglandin E2 |

| 9 | Sphingolipid signaling pathway | 0.0026 | 2/15 | 0.1333 | C00319 C00550 | Sphingosine, SM(d18:1/24:1(15Z)) |

| 10 | Serotonergic synapse | 0.0034 | 2/17 | 0.1176 | C00078 C00219 | L-Tryptophan, Arachidonic acid |

| 11 | Phenylalanine metabolism | 0.0034 | 3/60 | 0.0500 | C00079 C00082 C01772 | L-Phenylalanine, L-Tyrosine, 2-Hydroxycinnamic acid |

| 12 | Sphingolipid metabolism | 0.0072 | 2/25 | 0.0800 | C00319 C00550 | Sphingosine, SM(d18:1/24:1(15Z)) |

| 13 | Inflammatory mediator regulation of TRP channels | 0.0090 | 2/28 | 0.0714 | C00219 C00584 | Arachidonic acid, Prostaglandin E2 |

| 14 | Protein digestion and absorption | 0.0097 | 2/29 | 0.0690 | C00062 C00079 | L-Arginine, L-Phenylalanine |

| 15 | Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids | 0.0494 | 2/69 | 0.0290 | C00219 C16527 | Arachidonic acid |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Z.; Wei, Z.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Yu, T. Cartilaginous Metabolomics Reveals the Biochemical-Niche Fate Control of Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells. Cells 2022, 11, 2951. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11192951

Peng H, Zhang Y, Ren Z, Wei Z, Chen R, Zhang Y, Huang X, Yu T. Cartilaginous Metabolomics Reveals the Biochemical-Niche Fate Control of Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells. Cells. 2022; 11(19):2951. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11192951

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Haining, Yi Zhang, Zhongkai Ren, Ziran Wei, Renjie Chen, Yingze Zhang, Xiaohong Huang, and Tengbo Yu. 2022. "Cartilaginous Metabolomics Reveals the Biochemical-Niche Fate Control of Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells" Cells 11, no. 19: 2951. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11192951

APA StylePeng, H., Zhang, Y., Ren, Z., Wei, Z., Chen, R., Zhang, Y., Huang, X., & Yu, T. (2022). Cartilaginous Metabolomics Reveals the Biochemical-Niche Fate Control of Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells. Cells, 11(19), 2951. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11192951