Sympathetic Stimulation Upregulates the Ca2+ Channel Subunit, CaVα2δ1, via the β1 and ERK 1/2 Pathway in Neonatal Ventricular Cardiomyocytes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Animal Ethics Approval

2.2. Isolation of Neonatal Ventricular Cardiomyocytes

2.3. Treatment of Neonatal Ventricular Cardiomyocytes

2.4. Immunofluorescence and Surface Area Assessment

2.5. Western Blot

2.6. Patch-Clamp

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

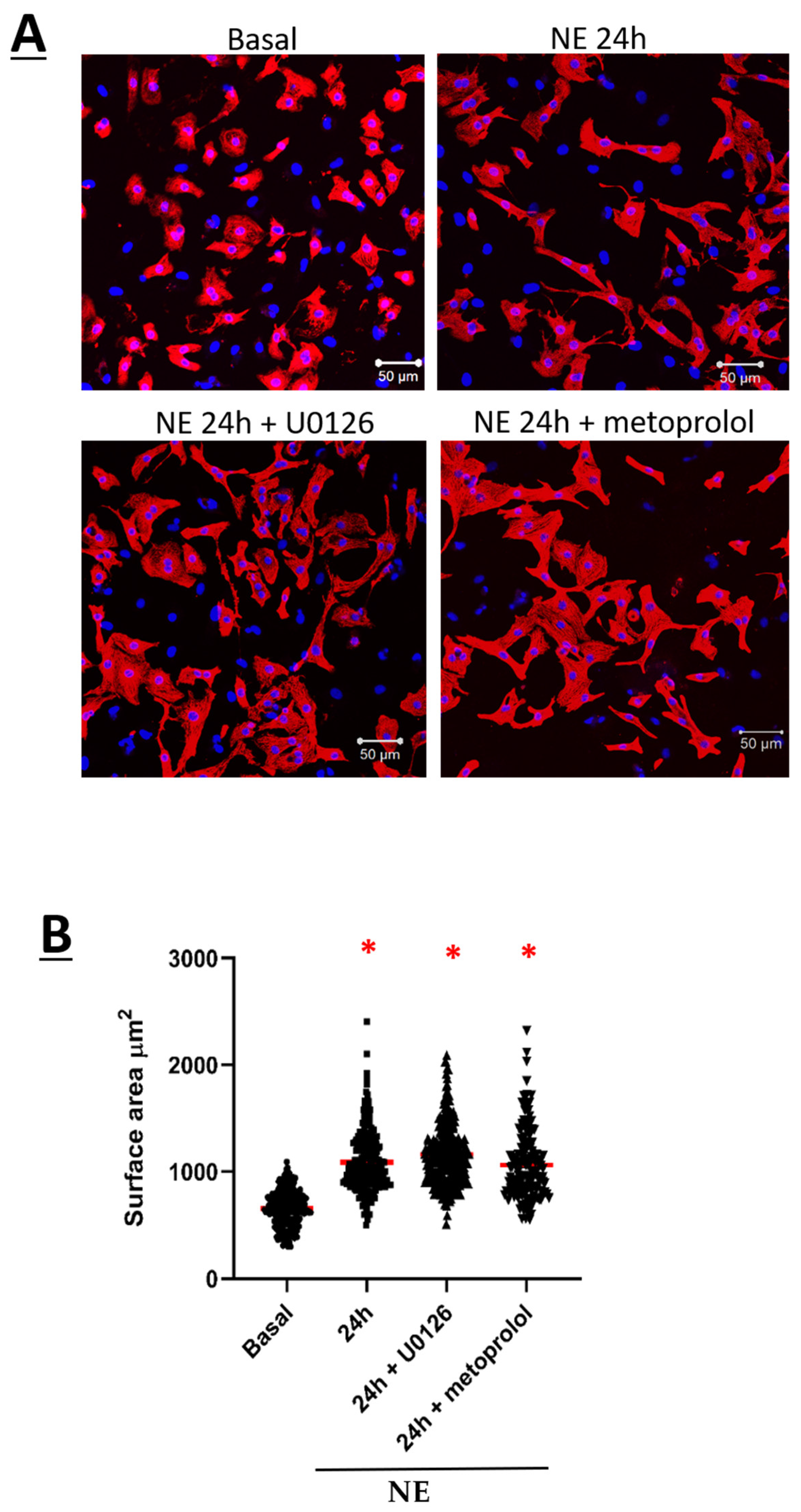

3.1. Norepinephrine Induced Neonatal Rat Ventricular Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy and Increased CaV1.2 Peak Current Density

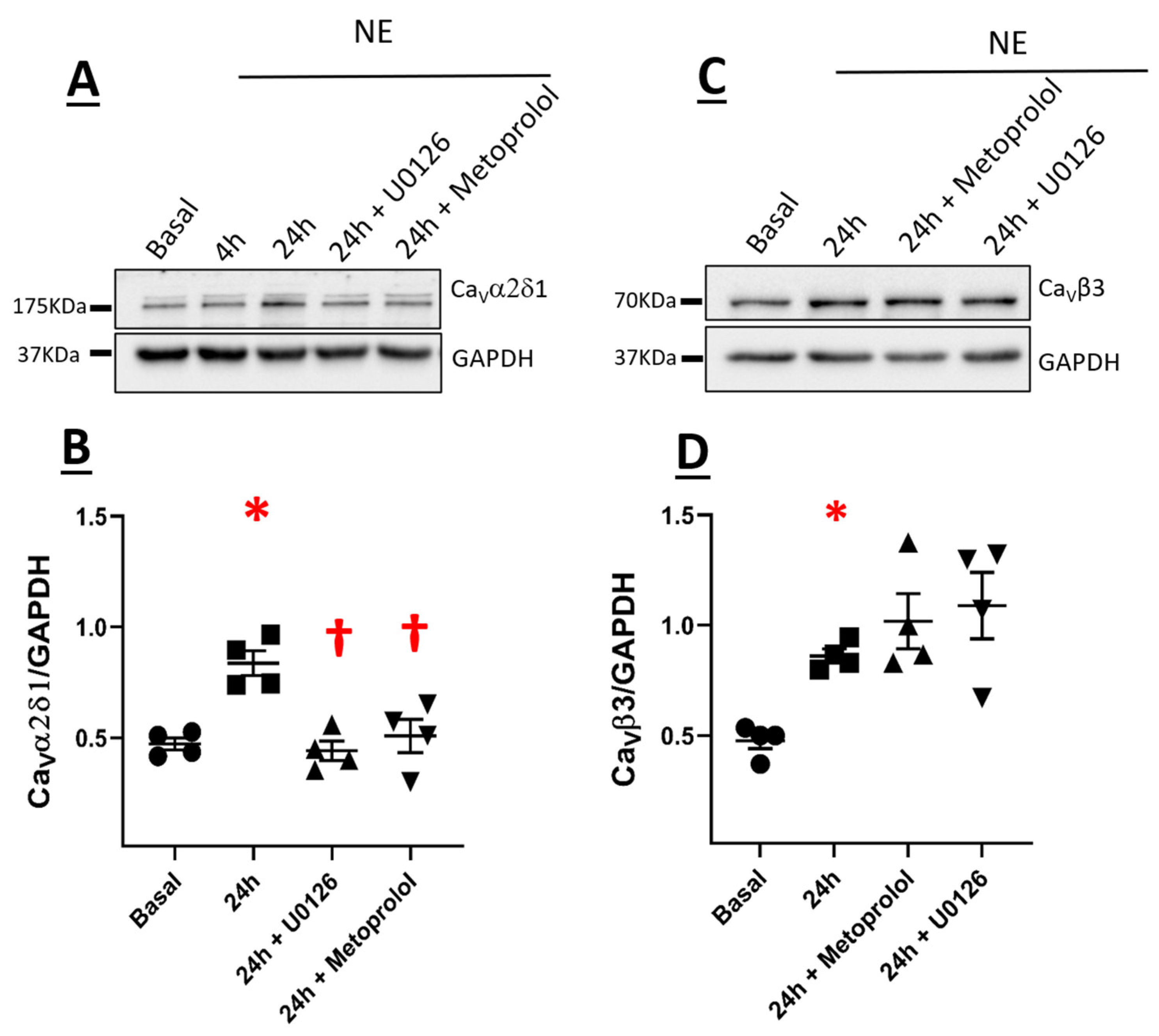

3.2. CaVα2δ1 and CaVβ3 Are Upregulated in Norepinephrine-Induced Hypertrophy of Neonatal Rat Ventricular Cardiomyocytes

3.3. The Subcellular Localization of CaVα2δ1 or CaVα1C Was Not Altered in Hypertrophic Neonatal Rat Ventricular Cardiomyocytes

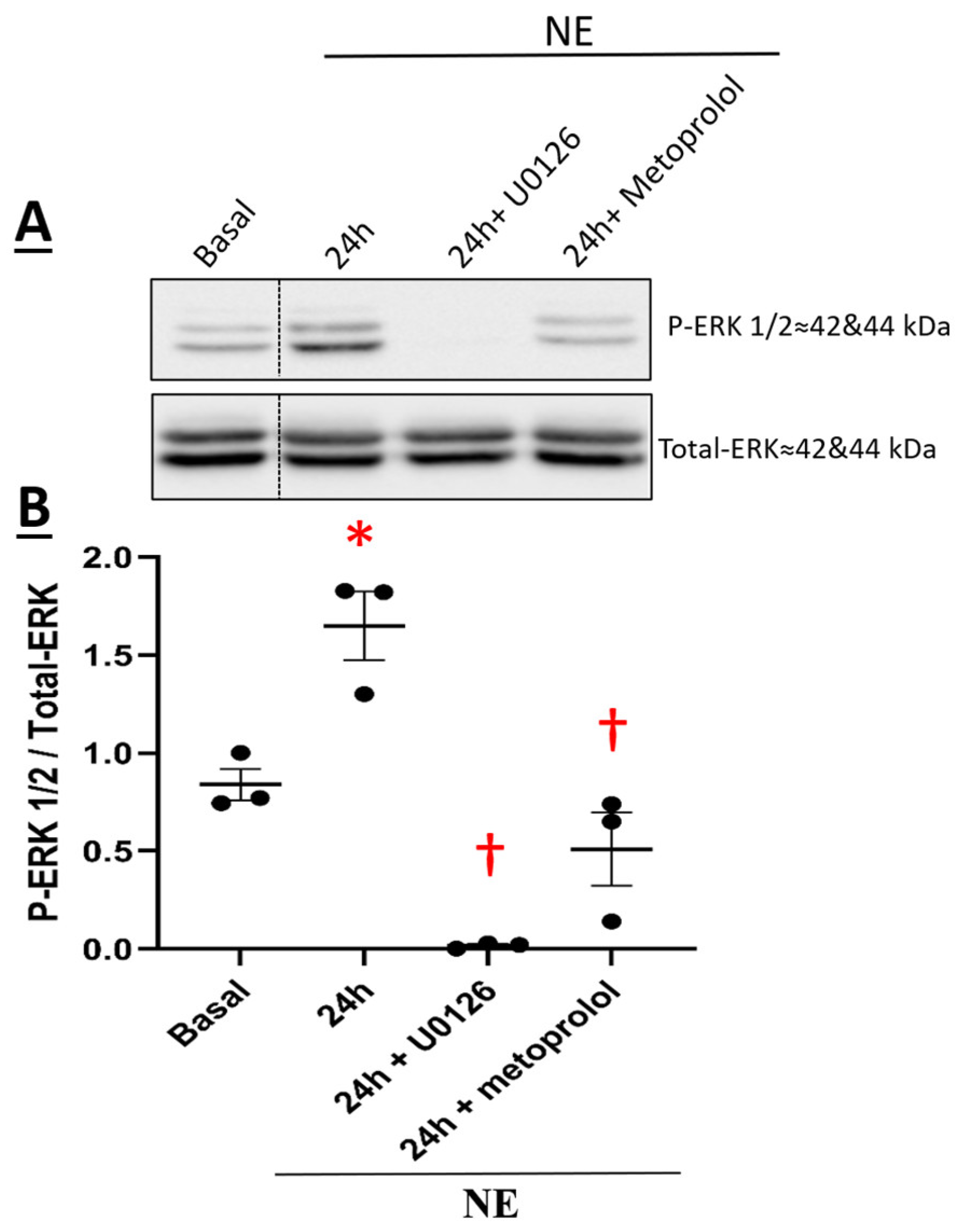

3.4. β1-Adrenergic Receptor-Mediated NE-Induced Upregulation of CaVα2δ1 via Recruitment of the Downstream Signaling Kinase ERK 1/2

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luo, M.; Anderson, M.E. Mechanisms of Altered Ca2+ Handling in Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2013, 113, 690–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eisner, D.A.; Caldwell, J.L.; Kistamás, K.; Trafford, A.W. Calcium and Excitation-Contraction Coupling in the Heart. Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkins, B.J.; Dai, Y.-S.; Bueno, O.F.; Parsons, S.A.; Xu, J.; Plank, D.M.; Jones, F.; Kimball, T.R.; Molkentin, J.D. Calcineurin/NFAT Coupling Participates in Pathological, but not Physiological, Cardiac Hypertrophy. Circ. Res. 2004, 94, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molkentin, J.; Lu, J.; Antos, C.L.; Markham, B.; Richardson, J.; Robbins, J.; Grant, S.R.; Olson, E.N. A Calcineurin-Dependent Transcriptional Pathway for Cardiac Hypertrophy. Cell 1998, 93, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, T. Role of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004, 63, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderone, A. Myocardial Hypertrophy and Regeneration. In Pathobiology of Human Disease; McManus, L.M., Mitchell, R.N., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderone, A. p38 MAPK and the compromised regenerative response of the infarcted adult heart. Cardiovasc. Regen. Med. 2017, 4, e1508. Available online: https://www.smartscitech.com/index.php/CRM/article/view/797 (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Fiedler, B. Interference of antihypertrophic molecules and signaling pathways with the Ca2+—calcineurin—NFAT cascade in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004, 63, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdin, B.; Shakeri, B.; Tétreault, M.-P.; Sauvé, R.; Lesage, S.; Parent, L. Functional Characterization of CaVα2δ Mutations Associated with Sudden Cardiac Death. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 2854–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katat, A.A.; Segura, E.; Parent, L. L-Type Calcium Channels in Health and Disease: The Case of Heart Failure. In Reference Module in Life Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briot, J.; Mailhot, O.; Bourdin, B.; Tétreault, M.-P.; Najmanovich, R.; Parent, L. A three-way inter-molecular network accounts for the CaVα2δ1-induced functional modulation of the pore-forming CaV1.2 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 7176–7188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, J.; Yan, Z.; Li, Z.; Qian, X.; Lu, S.; Dong, M.; Zhou, Q.; Yan, N. Structure of the voltage-gated calcium channel CaV1.1 at 3.6 Å resolution. Nature 2016, 537, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catterall, W.A. Structure and Regulation of Voltage-Gated Ca2+ Channels. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2000, 16, 521–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, T.; Puri, T.S.; Gerhardstein, B.L.; Chien, A.J.; Green, R.D.; Hosey, M.M. Identification and Subcellular Localization of the Subunits of L-type Calcium Channels and Adenylyl Cyclase in Cardiac Myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 19401–19407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Perez-Reyes, E.; Castellano, A.; Kim, H.S.; Bertrand, P.; Baggstrom, E.; Lacerda, A.E.; Wei, X.Y.; Birnbaumer, L. Cloning and expression of a cardiac/brain beta subunit of the L-type calcium channel. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hullin, R.; Singer-Lahat, D.; Freichel, M.; Biel, M.; Dascal, N.; Hofmann, F.; Flockerzi, V. Calcium channel beta subunit heterogeneity: Functional expression of cloned cDNA from heart, aorta and brain. EMBO J. 1992, 11, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolphin, A.C. The α2δ subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1828, 1541–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Briot, J.; Tétreault, M.-P.; Bourdin, B.; Parent, L. Inherited Ventricular Arrhythmias: The Role of the Multi-Subunit Structure of the L-Type Calcium Channel Complex. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 966, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templin, C.; Ghadri, J.-R.; Rougier, J.-S.; Baumer, A.; Kaplan, V.; Albesa, M.; Sticht, H.; Rauch, A.; Puleo, C.; Hu, D.; et al. Identification of a novel loss-of-function calcium channel gene mutation in short QT syndrome (SQTS6). Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buraei, Z.; Yang, J. The β Subunit of Voltage-Gated Ca2+ Channels. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 1461–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shakeri, B.; Bourdin, B.; Demers-Giroux, P.-O.; Sauvé, R.; Parent, L. A Quartet of Leucine Residues in the Guanylate Kinase Domain of CaVβ Determines the Plasma Membrane Density of the CaV2.3 Channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 32835–32847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bourdin, B.; Marger, F.; Wall-Lacelle, S.; Schneider, T.; Klein, H.; Sauvé, R.; Parent, L. Molecular Determinants of the CaVβ-induced Plasma Membrane Targeting of the CaV1.2 Channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 22853–22863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bourdin, B.; Briot, J.; Tétreault, M.-P.; Sauvé, R.; Parent, L. Negatively charged residues in the first extracellular loop of the L-type CaV1.2 channel anchor the interaction with the CaVα2δ1 auxiliary subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 17236–17249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tétreault, M.-P.; Bourdin, B.; Briot, J.; Segura, E.; Lesage, S.; Fiset, C.; Parent, L. Identification of Glycosylation Sites Essential for Surface Expression of the CaVα2δ1 Subunit and Modulation of the Cardiac CaV1.2 Channel Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 4826–4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Segura, E.; Bourdin, B.; Tétreault, M.-P.; Briot, J.; Allen, B.; Mayer, G.; Parent, L. Proteolytic cleavage of the hydrophobic domain in the CaVα2δ1 subunit improves assembly and activity of cardiac CaV1.2 channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 11109–11124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papa, A.; Kushner, J.; Hennessey, J.A.; Katchman, A.N.; Zakharov, S.I.; Chen, B.-X.; Yang, L.; Lu, R.; Leong, S.; Diaz, J.; et al. Adrenergic CaV1.2 Activation via Rad Phosphorylation Converges at α 1C I-II Loop. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meus, M.-A.; Hertig, V.; Villeneuve, L.; Jasmin, J.-F.; Calderone, A. Nestin Expressed by Pre-Existing Cardiomyocytes Recapitulated in Part an Embryonic Phenotype; Suppressive Role of p38 MAPK. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017, 232, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertig, V.; Matos-Nieves, A.; Garg, V.; Villeneuve, L.; Mamarbachi, M.; Caland, L.; Calderone, A. Nestin expression is dynamically regulated in cardiomyocytes during embryogenesis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 3218–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, H.; Fujio, Y.; Yamaguchi, O. Calcium dependent signaling in cardiac hypertrophy and cell death. Clin. Calcium 2013, 23, 505–515. [Google Scholar]

- Houser, S.R.; Carnell, L.H. Ca2+ Signaling Domains Responsible for Cardiac Hypertrophy and Arrhythmias. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanaka, S.; Fujio, Y.; Nakayama, H. Caveolae-Specific CaMKII Signaling in the Regulation of Voltage-Dependent Calcium Channel and Cardiac Hypertrophy. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fu, Y.; Westenbroek, R.E.; Scheuer, T.; Catterall, W.A. Basal and β-adrenergic regulation of the cardiac calcium channel CaV1.2 requires phosphorylation of serine 1700. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 16598–16603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simpson, P. Norepinephrine-stimulated hypertrophy of cultured rat myocardial cells is an alpha 1 adrenergic response. J. Clin. Investig. 1983, 72, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duran, P.; Sandoval, A.; González-Ramírez, R.; Zarco, N.; Felix, R. Regulation of the Ca2+ channel α2δ-1 subunit expression by epidermal growth factor via the ERK/ELK-1 signaling pathway. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 319, E232–E244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.; Reddy, G.R.; Wallukat, G.; Xiang, Y.K.; Steinberg, S.F. β1-adrenergic receptor O-glycosylation regulates N-terminal cleavage and signaling responses in cardiomyocytes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Post, G.R.; Goldstein, D.; Thuerauf, D.J.; Glembotski, C.C.; Brown, J.H. Dissociation of p44 and p42 Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Activation from Receptor-induced Hypertrophy in Neonatal Rat Ventricular Myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 8452–8457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lymperopoulos, A.; Rengo, G.; Koch, W.J. Adrenergic Nervous System in Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2013, 113, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Katat, A.; Zhao, J.; Calderone, A.; Parent, L. Sympathetic Stimulation Upregulates the Ca2+ Channel Subunit, CaVα2δ1, via the β1 and ERK 1/2 Pathway in Neonatal Ventricular Cardiomyocytes. Cells 2022, 11, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11020188

Al Katat A, Zhao J, Calderone A, Parent L. Sympathetic Stimulation Upregulates the Ca2+ Channel Subunit, CaVα2δ1, via the β1 and ERK 1/2 Pathway in Neonatal Ventricular Cardiomyocytes. Cells. 2022; 11(2):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11020188

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Katat, Aya, Juan Zhao, Angelino Calderone, and Lucie Parent. 2022. "Sympathetic Stimulation Upregulates the Ca2+ Channel Subunit, CaVα2δ1, via the β1 and ERK 1/2 Pathway in Neonatal Ventricular Cardiomyocytes" Cells 11, no. 2: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11020188