The Promising Therapeutic and Preventive Properties of Anthocyanidins/Anthocyanins on Prostate Cancer

Abstract

:1. Introduction

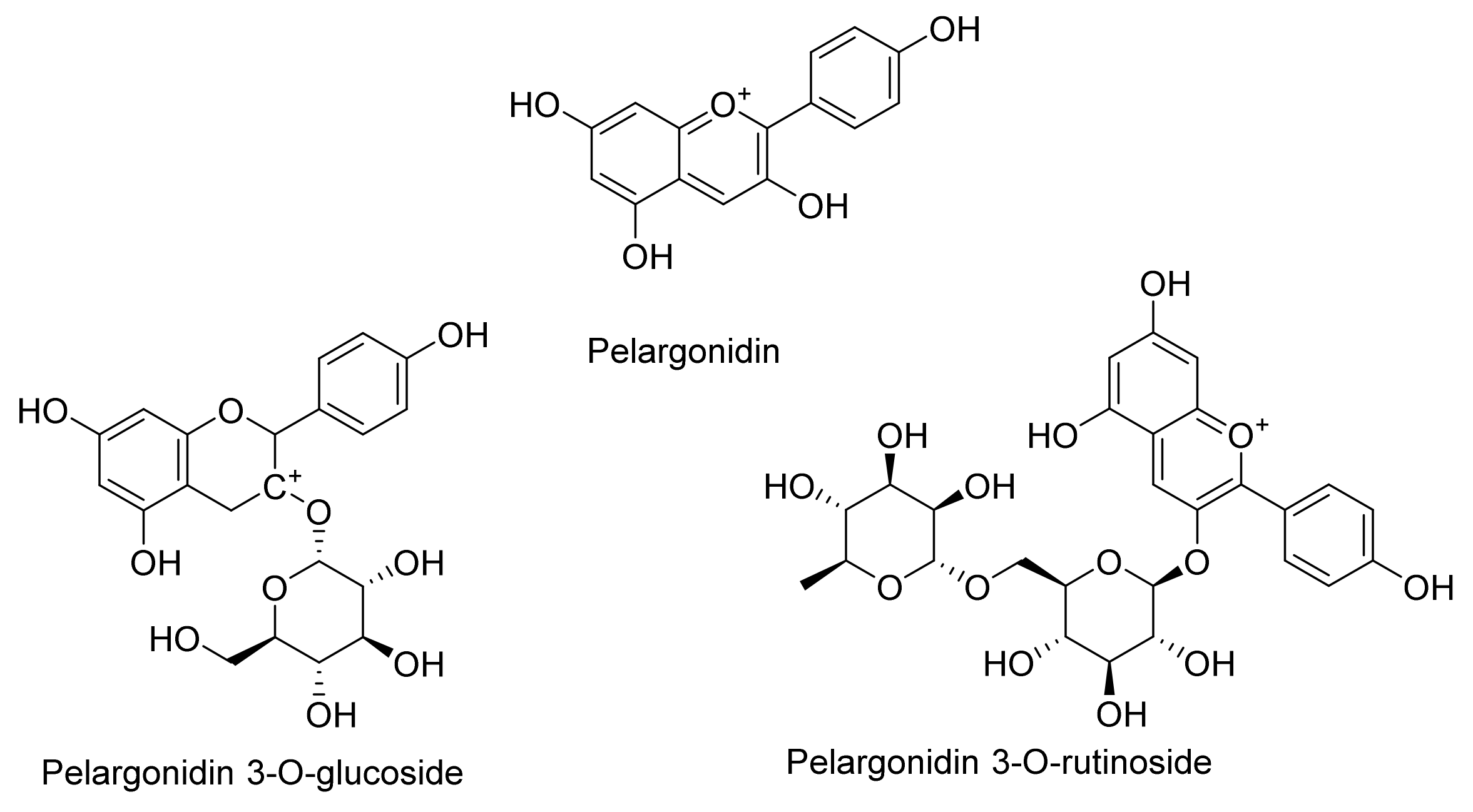

2. Chemistry of Anthocyanidins and Anthocyanins

Chemical Stability and Bioavailability of Anthocyanidins/Anthocyanins

3. Natural Sources of Anthocyanidins/Anthocyanins

4. Anti-Prostate Cancer Properties of Anthocyanidins/Anthocyanins

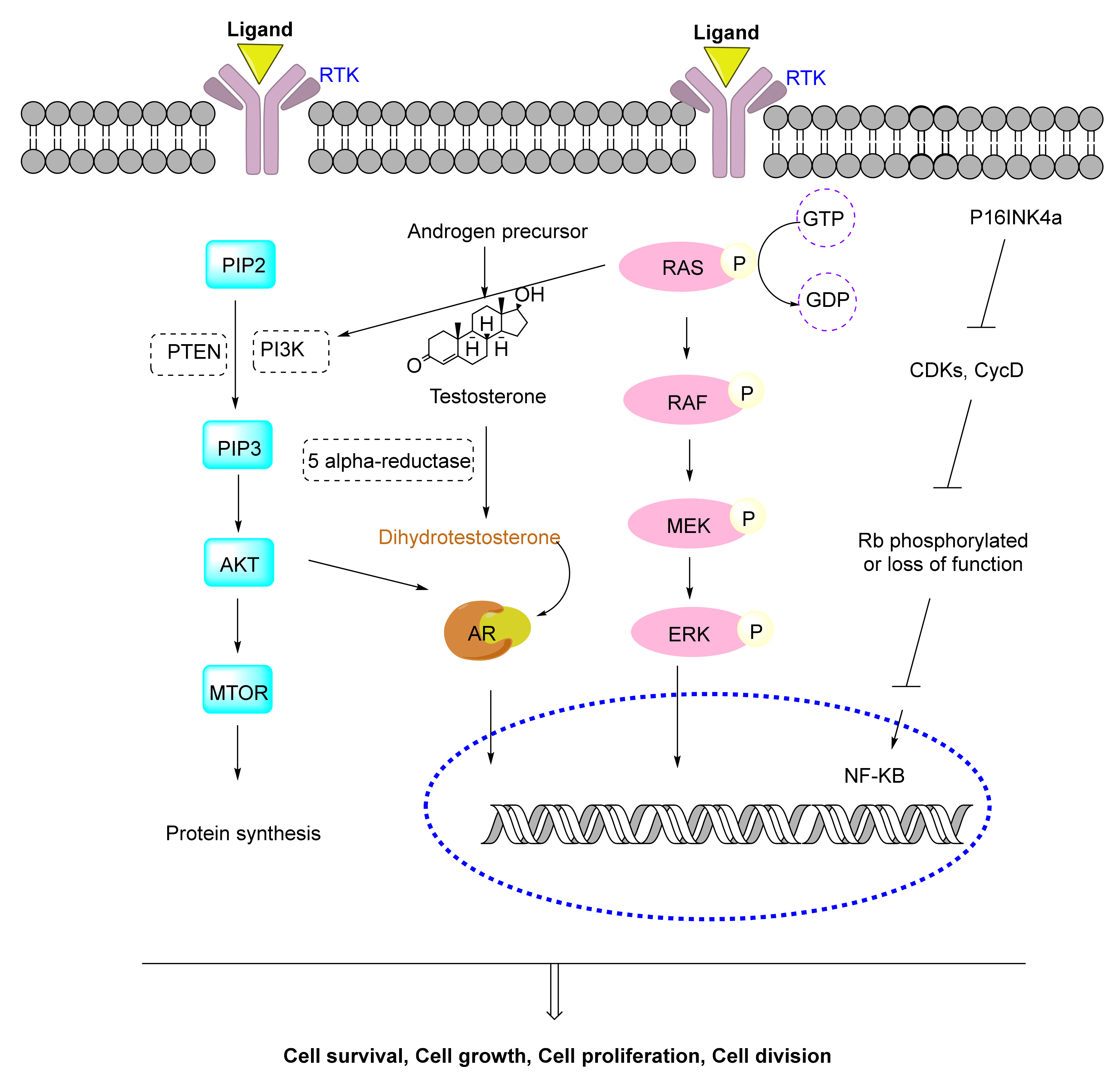

4.1. Metabolic Pathways of Prostate Cancer

4.2. In Vitro Screening of Anthocyanidins/Anthocyanins on Prostate Cancer

4.2.1. Rich Anthocyanidins/Anthocyanins Plant Extracts

Rice

Grape

Cranberry

Rhoeo discolor

Maize

Strawberry

Cherry

Ixora coccinea

Potato

Acanthopanax senticosus

Lycium ruthenicum

Hibiscus sabdariffa

Blueberry

Blackberry and Raspberry

Pomegranate

Black Carrots

4.2.2. In Vitro Screening of Pure Anthocyanidin/Anthocyanin Derivatives on Prostate Cancer Cell Lines

Delphinidin

Cyanidin-3-O-Glucoside

4.3. In Vivo Experiments Evaluating the Effectiveness of Anthocyanidins/Anthocyanins on Prostate Cancer

4.3.1. Mice Model Experiments

4.3.2. Rat Model Experiments

4.4. The Efficacy Assessment of Anthocyanidins/Anthocyanins on Prostate Cancer through Clinical Trials

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACD | anthocyanidin |

| ACN | anthocyanin |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| STAT-3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| CatL | cathepsin L |

| ER-α | Estrogen receptor-alpha |

| CDK | Cyclin-dependent kinase |

| PrEC | Normal prostate epithelial cells |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| PSA | Prostate-specific antigen |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa B |

| MMP-9 | Matrix metallopeptidase 9 |

| DU14 | Androgen-sensitive prostate cancer |

| LnCap | Androgen-independent prostate cancer |

| CRPC | castrate-resistant prostate cancer |

| BPH-1 | Epithelial cells of benign prostatic hypertrophy |

| LNCaP | Androgen-dependent tumoral prostatic cells |

| DU145 | Androgen-resistant tumoral prostatic cells |

| AIF | Apoptosis-inducing factor |

| C3G | Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside |

| PGG | petunidin 3-O-[6-O-(4-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl)-β-d- glucopyranoside]-5-O-[β-d-glucopyranoside] |

| MMP | matrix metalloproteinase |

| PC | prostate cancer |

| pSTAT3 | phosphorylated-Signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, M.Y.; Rathkopf, D.E.; Kantoff, P. Treatment of Advanced Prostate Cancer. Annu. Rev. Med. 2019, 70, 479–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIH. A Story of Discovery: Natural Compound Helps Treat Breast and Ovarian Cancers. Published 31 March 2015. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/research/progress/discovery/taxol (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Kwok, K.K.; Vincent, E.C.; Gibson, J.N. Antineoplastic Drugs. In Pharmacology and Therapeutics for Dentistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 530–562. [Google Scholar]

- Pullaiah, T.; Raveendran, V. Camptothecin: Chemistry, biosynthesis, analogs, and chemical synthesis. In Camptothecin and Camptothecin Producing Plants; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 47–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dockery, L.; Daniel, M.-C. Dendronized Systems for the Delivery of Chemotherapeutics. Adv. Cancer Res. 2018, 139, 85–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Bhandari, C.; Sharma, P.; Agnihotri, N. Role of Piperine in Chemoresistance. In Role of Nutraceuticals in Chemoresistance to Cancer; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 259–286. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.S.; Stoner, G.D. Anthocyanins and their role in cancer prevention. Cancer Lett. 2008, 269, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, B.-W.; Gong, C.-C.; Song, H.-F.; Cui, Y.-Y. Effects of anthocyanins on the prevention and treatment of cancer. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1226–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, J.; Zhou, H.; Song, L.; Yang, Z.; Qiu, M.; Wang, J.; Shi, S. Anthocyanins: Promising natural products with diverse pharmacological activities. Molecules 2021, 26, 3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattioli, R.; Francioso, A.; Mosca, L.; Silva, P. Anthocyanins: A Comprehensive Review of Their Chemical Properties and Health Effects on Cardiovascular and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2020, 25, 3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Ovando, A.; de Pacheco-Hernández, M.L.; Páez-Hernández, M.E.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Galán-Vidal, C.A. Chemical studies of anthocyanins: A review. Food Chem. 2009, 113, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Cappellini, F.; Reiner, Z.; Zorzan, D.; Imran, M.; Sener, B.; Kilic, M.; El-Shazly, M.; Fahmy, N.M.; et al. The Therapeutic Potential of Anthocyanins: Current Approaches Based on Their Molecular Mechanism of Action. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, H.E.; Azlan, A.; Tang, S.T.; Lim, S.M. Anthocyanidins and anthocyanins: Colored pigments as food, pharmaceutical ingredients, and the potential health benefits. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 61, 1361779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faria, A.; Fernandes, I.; Mateus, N.; Calhau, C. Bioavailability of anthocyanins. In Natural Products: Phytochemistry, Botany and Metabolism of Alkaloids, Phenolics and Terpenes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 2465–2487. ISBN 9783642221446. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J. Bioavailability of anthocyanins. Drug Metab. Rev. 2014, 46, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eker, M.E.; Aaby, K.; Budic-Leto, I.; Brncic, S.R.; El, S.N.; Karakaya, S.; Simsek, S.; Manach, C.; Wiczkowski, W.; De Pascual-Teresa, S. A review of factors affecting anthocyanin bioavailability: Possible implications for the inter-individual variability. Foods 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, J.; Celli, G.B.; Brooks, M.S. Chapter 1. Natural Sources of Anthocyanins. In Anthocyanins from Natural Sources: Exploiting Targeted Delivery for Improved Health; The Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, Y.S.; Guan, Y.; Hwan Moon, K.; Williams, L.L. Anthocyanins: Natural Sources and Traditional Therapeutic Uses. In Flavonoids—A Coloring Model for Cheering Up Life; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, S.; Song, Q.; Chen, G.; Cheng, E.; Chen, W.; Cole, R.; Wu, Z.; Pascal, L.E.; Wang, K.; Wipf, P.; et al. Regulation and targeting of androgen receptor nuclear localization in castration-resistant prostate cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, 141335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonergan, P.; Tindall, D. Androgen receptor signaling in prostate cancer development and progression. J. Carcinog. 2011, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, M.E.; Li, J.; Xu, H.E.; Melcher, K.; Yong, E.L. Androgen receptor: Structure, role in prostate cancer and drug discovery. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2015, 36, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Toren, P.; Zoubeidi, A. Targeting the PI3K/Akt pathway in prostate cancer: Challenges and opportunities (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 45, 1793–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Phin, S.; Moore, M.W.; Cotter, P.D. Genomic rearrangements of PTEN in prostate cancer. Front. Oncol. 2013, 3, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Basnet, R.; Basnet, B.B. Overview of Protein Kinase B Enzyme:a Potential Target for breast and Prostate Cancer. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2020, 13, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.J.; Der, C.J. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene 2007, 26, 3291–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cargnello, M.; Roux, P.P. Activation and Function of the MAPKs and Their Substrates, the MAPK-Activated Protein Kinases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 50–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kitajima, S.; Li, F.; Takahashi, C. Tumor milieu controlled by RB tumor suppressor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Subramanian, M.; Jones, M.F.; Lal, A. Long non-coding RNAs embedded in the Rb and p53 pathways. Cancers 2013, 5, 1655–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jin, X.; Ding, D.; Yan, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, B.; Ma, L.; Ye, Z.; Ma, T.; Wu, Q.; Rodrigues, D.N.; et al. Phosphorylated RB Promotes Cancer Immunity by Inhibiting NF-κB Activation and PD-L1 Expression. Mol. Cell 2019, 73, 22–35.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ranjan, A.; Ramachandran, S.; Gupta, N.; Kaushik, I.; Wright, S.; Srivastava, S.; Das, H.; Srivastava, S.; Prasad, S.; Srivastava, S.K. Role of Phytochemicals in Cancer Prevention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Flora, S.; Ferguson, L.R. Overview of mechanisms of cancer chemopreventive agents. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2005, 591, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banjerdpongchai, R.; Wudtiwai, B.; Sringarm, K. Cytotoxic and apoptotic-inducing effects of purple rice extracts and chemotherapeutic drugs on human cancer cell lines. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 6541–6548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Burton, L.J.; Smith, B.A.; Smith, B.N.; Loyd, Q.; Nagappan, P.; McKeithen, D.; Wilder, C.L.; Platt, M.O.; Hudson, T.; Odero-Marah, V.A. Muscadine grape skin extract can antagonize Snail-cathepsin L-mediated invasion, migration and osteoclastogenesis in prostate and breast cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 2015, 36, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, V.C.; Boff, L.; Vizzotto, M.; Calvete, E.; Reginatto, F.H.; Simões, C.M.O. Berries grown in Brazil: Anthocyanin profiles and biological properties. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 4331–4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Bubba, M.; Di Serio, C.; Renai, L.; Scordo, C.V.A.; Checchini, L.; Ungar, A.; Tarantini, F.; Bartoletti, R. Vaccinium myrtillus L. extract and its native polyphenol-recombined mixture have anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects on human prostate cancer cell lines. Phyther. Res. 2021, 35, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Déziel, B.; MacPhee, J.; Patel, K.; Catalli, A.; Kulka, M.; Neto, C.; Gottschall-Pass, K.; Hurta, R. American cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) extract affects human prostate cancer cell growth via cell cycle arrest by modulating expression of cell cycle regulators. Food Funct. 2012, 3, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdowska, M.; Leszczyńska, T.; Koronowicz, A.; Piasna-Słupecka, E.; Dziadek, K. Comparative study of young shoots and the mature red headed cabbage as antioxidant food resources with antiproliferative effect on prostate cancer cells. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 43021–43034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Seeram, N.P.; Lee, R.; Feng, L.; Heber, D. Isolation and identification of strawberry phenolics with antioxidant and human cancer cell antiproliferative properties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, J.; Briscoe, T.; Hou, M.; Goodman, C.; Kata, S.; Ross, H.; McDougall, G.; Stewart, D.; Richers, A. Strawberry polyphenols are equally cytotoxic to tumourigenic and normal human breast and prostate cell lines. Int. J. Oncol. 2009, 34, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Urias-Lugo, D.A.; Heredia, J.B.; Muy-Rangel, M.D.; Valdez-Torres, J.B.; Serna-Saldívar, S.O.; Gutiérrez-Uribe, J.A. Anthocyanins and Phenolic Acids of Hybrid and Native Blue Maize (Zea mays L.) Extracts and Their Antiproliferative Activity in Mammary (MCF7), Liver (HepG2), Colon (Caco2 and HT29) and Prostate (PC3) Cancer Cells. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2015, 70, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambrano, A.; Raybaudi-Massilia, R.; Arvelo, F.; Sojo, F. Cytotoxic and antioxidant properties in vitro of functional beverages based on blackberry (Rubus glaucus Benth) and soursop (Annona muricata L.) pulps. Funct. Foods Health Dis. 2018, 8, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.R.; Vaz, C.V.; Catalão, B.; Ferreira, S.; Cardoso, H.J.; Duarte, A.P.; Socorro, S. Sweet Cherry Extract Targets the Hallmarks of Cancer in Prostate Cells: Diminished Viability, Increased Apoptosis and Suppressed Glycolytic Metabolism. Nutr. Cancer 2020, 72, 917–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreelakshmi, S.V.; Chaitrashree, N.; Kumar, S.S.; Shetty, N.P.; Giridhar, P. Fruits of Ixora coccinea are a rich source of phytoconstituents, bioactives, exhibit antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity against human prostate carcinoma cells and development of RTS beverage. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, 15656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettig, M.B.; Heber, D.; An, J.; Seeram, N.P.; Rao, J.Y.; Liu, H.; Klatte, T.; Belldegrun, A.; Moro, A.; Henning, S.M.; et al. Pomegranate extract inhibits androgen-independent prostate cancer growth through a nuclear factor- B-dependent mechanism. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 2662–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reddivari, L.; Vanamala, J.; Chintharlapalli, S.; Safe, S.H.; Miller, J.C. Anthocyanin fraction from potato extracts is cytotoxic to prostate cancer cells through activation of caspase-dependent and caspase-independent pathways. Carcinogenesis 2007, 28, 2227–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jongsomchai, K.; Leardkamolkarn, V.; Mahatheeranont, S. A rice bran phytochemical, cyanidin 3-glucoside, inhibits the progression of PC3 prostate cancer cell. Anat. Cell Biol. 2020, 53, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevimli-Gur, C.; Cetin, B.; Akay, S.; Gulce-Iz, S.; Yesil-Celiktas, O. Extracts from Black Carrot Tissue Culture as Potent Anticancer Agents. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2013, 68, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-H.; Chan, K.-C.; Sheu, J.-Y.; Hsuan, S.-W.; Wang, C.-J.; Chen, J.-H. Hibiscus sabdariffa leaf induces apoptosis of human prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 880–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matchett, M.D.; MacKinnon, S.L.; Sweeney, M.I.; Gottschall-Pass, K.T.; Hurta, R.A.R. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase activity in DU145 human prostate cancer cells by flavonoids from lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium): Possible roles for protein kinase C and mitogen-activated protein-kinase- mediated events. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2006, 17, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite-Legatti, A.V.; Batista, A.G.; Dragano, N.R.V.; Marques, A.C.; Malta, L.G.; Riccio, M.F.; Eberlin, M.N.; Machado, A.R.T.; de Carvalho-Silva, L.B.; Ruiz, A.L.T.G.; et al. Jaboticaba peel: Antioxidant compounds, antiproliferative and antimutagenic activities. Food Res. Int. 2012, 49, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karna, P.; Gundala, S.R.; Gupta, M.V.; Shamsi, S.A.; Pace, R.D.; Yates, C.; Narayan, S.; Aneja, R. Polyphenol-rich sweet potato greens extract inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Carcinogenesis 2011, 32, 1872–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Long, N.; Suzuki, S.; Sato, S.; Naiki-Ito, A.; Sakatani, K.; Shirai, T.; Takahashi, S. Purple corn color inhibition of prostate carcinogenesis by targeting cell growth pathways. Cancer Sci. 2013, 104, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Lim, J.D.; Choung, M.G. Studies on the anthocyanin profile and biological properties from the fruits of Acanthopanax senticosus (Siberian Ginseng). J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-L.; Mi, J.; Lu, L.; Luo, Q.; Liu, X.; Yan, Y.-M.; Jin, B.; Cao, Y.-L.; Zeng, X.-X.; Ran, L.-W. The main anthocyanin monomer of Lycium ruthenicum Murray induces apoptosis through the ROS/PTEN/PI3K/Akt/caspase 3 signaling pathway in prostate cancer DU-145 cells. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 1818–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeram, N.P.; Adams, L.S.; Hardy, M.L.; Heber, D. Total Cranberry Extract versus Its Phytochemical Constituents: Antiproliferative and Synergistic Effects against Human Tumor Cell Lines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 2512–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrenti, V.; Vanella, L.; Acquaviva, R.; Cardile, V.; Giofrè, S.; Di Giacomo, C. Cyanidin induces apoptosis and differentiation in prostate cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 47, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bin Hafeez, B.; Asim, M.; Siddiqui, I.A.; Adhami, V.M.; Murtaza, I.; Mukhtar, H. Delphinidin, a dietary anthocyanidin in pigmented fruits and vegetables: A new weapon to blunt prostate cancer growth. Cell Cycle 2008, 7, 3320–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonina, A.F.; Bonina, C. Compositions Based on Plant Extracts for Inhibition of the 5-Alpha Reductase. WO Patent WO2015132755A1, 5 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yeewa, R.; Naiki-Ito, A.; Naiki, T.; Kato, H.; Suzuki, S.; Chewonarin, T.; Takahashi, S. Hexane insoluble fraction from purple rice extract retards carcinogenesis and castration-resistant cancer growth of prostate through suppression of androgen receptor mediated cell proliferation and metabolism. Nutrients 2020, 12, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nassiri-Asl, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Review of the Pharmacological Effects of Vitis vinifera (Grape) and its Bioactive Constituents: An Update. Phyther. Res. 2016, 30, 1392–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signoretto, C.; Canepari, P.; Pruzzo, C.; Gazzani, G. Anticaries and antiadhesive properties of food constituents and plant extracts and implications for oral health. In Food Constituents and Oral Health: Current Status and Future Prospects; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 240–262. ISBN 9781845694180. [Google Scholar]

- García-Varela, R.; Fajardo Ramírez, O.R.; Serna-Saldivar, S.O.; Altamirano, J.; Cardineau, G.A. Cancer cell specific cytotoxic effect of Rhoeo discolor extracts and solvent fractions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 190, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capocchi, A.; Bottega, S.; Spanò, C.; Fontanini, D. Phytochemicals and antioxidant capacity in four Italian traditional maize (Zea mays L.) varieties. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 68, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Sotero, M.; González-Cortés, F.; García-Galindo, H.; Juarez-Aguilar, E.; Dorantes, M.R.; Chávez-Servia, J.; Oliart-Ros, R.; Guzmán-Gerónimo, R. Anthocyanin Profile of Red Maize Native from Mixteco Race and Their Antiproliferative Activity on Cell Line DU145. In From Biosynthesis to Human Health; BoD—Books on Demand: London, UK, 2017; pp. 393–404. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Sotero, M.Y.; Cruz-Hernández, C.D.; Oliart-Ros, R.M.; Chávez-Servia, J.L.; Guzmán-Gerónimo, R.I.; González-Covarrubias, V.; Cruz-Burgos, M.; Rodríguez-Dorantes, M. Anthocyanins of Blue Corn and Tortilla Arrest Cell Cycle and Induce Apoptosis on Breast and Prostate Cancer Cells. Nutr. Cancer 2020, 72, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.; Mortazavi, S.M.H.; Ramezanian, A.; Mahmoodi Sourestani, M.; Mottaghipisheh, J.; Iriti, M.; Vitalini, S. Prevention of decay and maintenance of bioactive compounds in strawberry by application of UV-C and essential oils. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 5310–5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampieri, F.; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Battino, M. Strawberry and human health: Effects beyond antioxidant activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 3867–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, F.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Alves, G.; Silva, L.R. Health Benefits of Prunus avium Plant Parts: An Unexplored Source Rich in Phenolic Compounds. Food Rev. Int. 2020, 36, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezekiel, R.; Singh, N.; Sharma, S.; Kaur, A. Beneficial phytochemicals in potato—A review. Food Res. Int. 2013, 50, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Kong, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, C.; Qu, Z.; Jin, L.; Wang, H. Composition Changes in Lycium ruthenicum Fruit Dried by Different Methods. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 737521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da-Costa-Rocha, I.; Bonnlaender, B.; Sievers, H.; Pischel, I.; Heinrich, M. Hibiscus sabdariffa L.—A phytochemical and pharmacological review. Food Chem. 2014, 165, 424–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vega, E.N.; Molina, A.K.; Pereira, C.; Dias, M.I.; Heleno, S.A.; Rodrigues, P.; Fernandes, I.P.; Barreiro, M.F.; Stojković, D.; Soković, M.; et al. Anthocyanins from Rubus fruticosus L. and Morus nigra L. applied as food colorants: A natural alternative. Plants 2021, 10, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaume, L.; Howard, L.R.; Devareddy, L. The blackberry fruit: A review on its composition and chemistry, metabolism and bioavailability, and health benefits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 5716–5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskra, J.N.; Schlicht, M.J.; Bosland, M.C. Effects of Black Raspberries and Their Ellagic Acid and Anthocyanin Constituents on Taxane Chemotherapy of Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottaghipisheh, J.; Ayanmanesh, M.; Babadayei-Samani, R.; Javid, A.; Sanaeifard, M.; Vitalini, S.; Iriti, M. Total anthocyanin, flavonoid, polyphenol and tannin contents of seven pomegranate cultivars grown in Iran. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2018, 17, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Özen, C.; Abu-Reidah, I.M.; Chigurupati, S.; Patra, J.K.; Horbanczuk, J.O.; Józwik, A.; Tzvetkov, N.T.; Uhrin, P.; Atanasov, A.G. Vasculoprotective effects of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.). Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smeriglio, A.; Denaro, M.; Barreca, D.; D’Angelo, V.; Germanò, M.P.; Trombetta, D. Polyphenolic profile and biological activities of black carrot crude extract (Daucus carota L. ssp. sativus var. atrorubens Alef.). Fitoterapia 2018, 124, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonesi, M.; Loizzo, M.R.; Menichini, F.; Tundis, R. Flavonoids in treating psoriasis. In Immunity and Inflammation in Health and Disease: Emerging Roles of Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods in Immune Support; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 281–294. ISBN 9780128054178. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, A.; Afaq, F.; Adhami, V.M.; Sarfaraz, S.; Mukhtar, H. Delphinidin, a major anthocyanin in pigmented fruits and vegetables induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells PC3. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 536–537. [Google Scholar]

- Bin Hafeez, B.; Siddiqui, I.A.; Asim, M.; Malik, A.; Afaq, F.; Adhami, V.M.; Saleem, M.; Din, M.; Mukhtar, H. A dietary anthocyanidin delphinidin induces apoptosis of human prostate cancer PC3 cells in vitro and in vivo: Involvement of nuclear factor-κB signaling. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 8564–8572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jang, H.; Ha, U.S.; Kim, S.J.; Il Yoon, B.; Han, D.S.; Yuk, S.M.; Kim, S.W. Anthocyanin extracted from black soybean reduces prostate weight and promotes apoptosis in the prostatic hyperplasia-induced rat model. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 12686–12691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, H.; Bae, W.J.; Kim, S.J.; Yuk, S.M.; Han, D.S.; Ha, U.S.; Hwang, S.Y.; Yoon, S.H.; Wang, Z.; Kim, S.W. The Effect of Anthocyanin on the Prostate in an Andropause Animal Model: Rapid Prostatic Cell Death by Apoptosis Is Partially Prevented by Anthocyanin Supplementation. World J. Men’s Health 2013, 31, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.F.; Tang, L.P.; He, R.R.; Xu, Z.; He, Q.Q.; Xiang, F.J.; Su, W.W.; Kurihara, H. Anthocyanins extract from bilberry enhances the therapeutic effect of pollen of Brassica napus L. on stress-provoked benign prostatic hyperplasia in restrained mice. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 1357–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.I.; Bae, W.J.; Choi, Y.S.; Kim, S.J.; Ha, U.S.; Hong, S.H.; Sohn, D.W.; Kim, S.W. Anti-inflammatory and Antimicrobial Effects of Anthocyanin Extracted from Black Soybean on Chronic Bacterial Prostatitis Rat Model. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2018, 24, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Bae, W.J.; Yuk, S.M.; Han, D.S.; Ha, U.S.; Hwang, S.Y.; Yoon, S.H.; Kim, S.W.; Han, C.H. Seoritae extract reduces prostate weight and suppresses prostate cell proliferation in a rat model of benign prostate hyperplasia. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 475876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ha, U.S.; Bae, W.J.; Kim, S.J.; Il Yoon, B.; Hong, S.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Hwang, T.K.; Hwang, S.Y.; Wang, Z.; Kim, S.W. Anthocyanin induces apoptosis of du-145 cells in vitro and inhibits xenograft growth of prostate cancer. Yonsei Med. J. 2015, 56, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, Y.J.; Fan, M.; Tang, Y.; Yang, H.P.; Hwang, J.Y.; Kim, E.K. In vivo effects of polymerized anthocyanin from grape skin on benign prostatic hyperplasia. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, N.H.; Jegal, J.; Kim, Y.N.; Heo, J.D.; Rho, J.R.; Yang, M.H.; Jeong, E.J. The effects of Aronia melanocarpa extract on testosterone-induced benign prostatic hyperplasia in rats, and quantitative analysis of major constituents depending on extract conditions. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamas, C.A.; Kido, L.A.; Hermes, T.A.; Nogueira-Lima, E.; Minatel, E.; Collares-Buzato, C.B.; Maróstica, M.R.; Cagnon, V.H.A. Brazilian berry extract (Myrciaria jaboticaba): A promising therapy to minimize prostatic inflammation and oxidative stress. Prostate 2020, 80, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.N.; Xie, W.H.; Zheng, Y.X.; Cao, J.P.; Cao, P.R.; Chen, Q.J.; Li, X.; Sun, C. De The growth of SGC-7901 tumor xenografts was suppressed by Chinese bayberry anthocyanin extract through upregulating KLF6 gene expression. Nutrients 2016, 8, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ganesan, K.; Xu, B. A critical review on polyphenols and health benefits of black soybeans. Nutrients 2017, 9, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gu, J.; Ahn-Jarvis, J.H.; Riedl, K.M.; Schwartz, S.J.; Clinton, S.K.; Vodovotz, Y. Characterization of black raspberry functional food products for cancer prevention human clinical trials. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 3997–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hamilton, K.; Bennett, N.C.; Purdie, G.; Herst, P.M. Standardized cranberry capsules for radiation cystitis in prostate cancer patients in New Zealand: A randomized double blinded, placebo controlled pilot study. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herst, P.M.; Aumata, A.; Sword, V.; Jones, R.; Purdie, G.; Costello, S. Cranberry capsules are not superior to placebo capsules in managing acute non-haemorrhagic radiation cystitis in prostate cancer patients: A phase III double blinded randomised placebo controlled clinical trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2020, 149, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Ozleyen, A.; Boyunegmez Tumer, T.; Oluwaseun Adetunji, C.; El Omari, N.; Balahbib, A.; Taheri, Y.; Bouyahya, A.; Martorell, M.; Martins, N.; et al. Natural Products and Synthetic Analogs as a Source of Antitumor Drugs. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, M.A. Phytochemicals as Potential Anticancer Drugs: Time to Ponder Nature’s Bounty. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 8602879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Anthocyanin Source | Cell Line | Effect | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purple rice extract | LNCaP | Extract at 200 µg/mL significantly reduced the viability of prostate cancer cells after 48 h | [33] |

| Muscadine grape skin extract | LNCaP | The extract decreased Snail and pSTAT3 expression and abrogated Snail-mediated CatL activity, migration, and invasion | [34] |

| ARCaP-E | |||

| Brazilian native fruits, pitanga (red and purple) and araçá (yellow and red), as well as strawberry cultivars Albion, Aromas, and Camarosa, blackberry cultivar Tupy, and blueberry cultivar Bluegen | DU145 | No cytotoxicity was found | [35] |

| Vaccinium myrtillus berry extract | LNCaP | Apoptotic rate (early and late) was statistically higher in tested cell lines exposed to Vaccinium myrtillus berry extract compared to control. | [36] |

| PC3 and DU-145 | Anchorage-dependent and anchorage-independent growth inhibition were seen | ||

| American cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) extract | DU145 | 10, 25 and 50 µg/mL of the extract significantly decreased the cellular viability of DU145 cells. | [37] |

| The extract at 25 and 50 µg/mL also lessened the proportion of cells in the G2-M phase of the cell cycle and increased the proportion of cells in the G1 phase after 6h in prostate carcinoma. | |||

| Red cabbage | DU145 | After 48 and 72 h 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5% juice reduced the proliferation of prostate cancer cell lines compared to the control group. | [38] |

| LNCaP | |||

| Strawberries (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) | LNCaP | Crude extracts (250 µg/mL) and pure compounds including C3G, pelargonidin, pelargonidin-3-glucoside, and pelargonidin-3-rutinoside (100 µg/mL) inhibited the growth of tested cancer cells significantly | [39] |

| DU145 | |||

| Strawberry | P21 | The strawberry extract was cytotoxic with doses of ~5 μg/mL causing a 50% reduction in cell survival in both the normal and the tumor lines. | [40] |

| P21 tumor cell line 1 and 2 | |||

| LNCaP | |||

| PC3 | |||

| Blue Maize (Zea mays L.) | PC3 | PC3 treated with 5 mg/mL of acidified and non-acidified extracts demonstrated cell viability in the range of ~30 to 70% | [41] |

| Blackberry (Rubus glaucus B.) and soursop (Annona muricata L.) | PC3 | Blackberry pulp and soursop pulp recorded cytotoxic effect with an IC50 of 1.81 ± 1.68% v/v and 1.34 ± 1.06% v/v, respectively | [42] |

| Sweet Cherry | PNT1A | The extract reduced the cell viability after 72 h at 2, 20, and 200 µg/mL compared to the control group MTT assay. | [43] |

| LNCaP | |||

| PC3 | |||

| Ixora coccinea (fruits) | LNCaP.FGC | The fruit extract exhibited anticancer activity against LNCaP.FGC cells with an IC50 value of 34.09 mg/mL. | [44] |

| Pomegranate extract | LNCaP | 240 mL solution inhibited NF-κB and cell viability of prostate cancer cell lines in a dose-dependent fashion. | [45] |

| LAPC4 | |||

| DU145 | |||

| Potato phenolics and their fractions | LNCaP | 5 mg chlorogenic acid eq/mL inhibited cell proliferation and increased the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 levels in both LNCaP and PC3 cells. | [46] |

| PC3 | |||

| Thai rice (Luempua cultivar) | PC3 | Thai rice showed cell viability with IC50 value of 167.8 ± 0.06 µM. | [47] |

| Black carrots | PC3 | Cell viabilities were between 58 and 77% at a concentration of 100 μg/mL of extract. | [48] |

| Hibiscus sabdariffa | LNCaP | IC50 = 2.5 mg/mL against LNCaP cells viability. | [49] |

| PC3 | |||

| DU145 | |||

| Lowbush blueberry | DU145 | Inhibition of MMP9 activity at 0.5 and 1.0 mg of crude fraction/mL was seen. Also, 1.0 mg/mL extract decreased the gelatinolytic activity of the activated isoforms of MMP-2 and complete inhibition of the pro-MMP-2, with an increase in TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 action. | [50] |

| (Vaccinium angustifolium): | |||

| Jaboticaba peel | PC3 | The non-polar extract was the most active agents against prostate cancer cells with GI50 = 13.8 μg/mL. | [51] |

| Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) | C4-2 | The extract significantly inhibited cell proliferation of all prostate cancer cells with IC50 values in the range of 145–315 µg/mL. IC50 of extract in normal prostate epithelial cells (PrEC and RWPE-1) was between 1000 and 1250 µg/mL. | [52] |

| LNCaP | |||

| DU145 | |||

| C4-2B | |||

| PC3 | |||

| PrEC | |||

| RWPE-1 | |||

| Purple corn | LNCaP | Purple corn color at 50 and 100 ppm inhibited the proliferation of LNCaP cells by decreasing the expression of cyclin D1 and inhibiting the G1 stage of the cell cycle. | [53] |

| Acanthopanax senticosus (Siberian Ginseng) | LNCap | Cyanidin-3-O-(2″-O-xylosyl) glucoside showed potent anticancer effects with IC50 of 5.2 µg/mL | [54] |

| petunidin 3-O-[6-O-(4-O-(trans-p-coumaroyl)- α-L-rhamnopyranosyl)- β-D-glucopyranoside]-5-O-[ β-D-glucopyranoside] extracted from Lycium ruthenicum Murray | DU145 | The IC50 viability of the compound against DU145 cells was about 361.58 µg/mL. The main anthocyanin monomer also inhibited cell proliferation, induced apoptosis, and promoted cell cycle arrest at the S phase. | [55] |

| Cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon Ait.) | RWPE-1, RWPE-2, 22Rv1 | Total cranberry extract and all fractions (200 µg/mL) showed ≥50% antiproliferative activity against prostate cancer cells. Total polyphenols fraction as the most active one exhibited RWPE-1, 95%; RWPE-2, 95%; 22Rv1, 99.6% anti-proliferation potentials. | [56] |

| C3G | DU145 | Compound produced significant anti-proliferative effects at 6 µM compared to the control group. Also, activation of caspase-3 and induction of p21 protein expression were seen at 50 and 100 µM. | [57] |

| LnCap | |||

| Delphinidin | PC3 | Pure compound at 30–300 μM resulted in the induction of cyclin kinase inhibitors p21/WAF1 and p27/KIP1, down-regulation of cyclin E, D1, and D2, and cyclin-dependent kinase 2, 4, and 6. | [58] |

| Applied Species | Diet | Supplement | Anthocyanin Dosage | Effect/Observation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athymic (nu/nu) male nude mice | An autoclaved diet ad libitum | Delphinidin | 2 mg/animal in 100 AL of 1:10 ratio of DMSO three times a week for 12 weeks | Reduced the expression of NF-κB/p65, Bcl-2, Ki67, and PCNA | [81] |

| 12-week-old Sprague-Dawley male rats | A diet ad libitum | Anthocyanin extracted from black soybean | 40, 80, and 160 mg/kg of anthocyanin daily for 4 weeks | Decreased the volume and suppressing the proliferation of the prostate | [82] |

| 6-week-old male nude mice | Normal diet | Polyphenol-rich sweet potato greens extract | 400 mg/kg polyphenol-rich sweet potato greens extract daily for 6 weeks | Inhibited growth and progression of prostate tumor xenografts by 69% in nude mice | [52] |

| 12-week-old male Sprague-Dawley rats | n.d | Anthocyanin extracted from the seed coat of the black soybean | 160 mg/kg of anthocyanin daily for 8 weeks | Prevented the rapid prostatic cell death by apoptosis in the prostate in an animal model of andropause | [83] |

| 7-week-old male Kunming mice | Standard diet | Anthocyanin extract from bilberry | 200 mg/kg of anthocyanins extract from bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) | Enhanced the therapeutic effect of Pollen of Brassica napus L. on stress-provoked benign prostatic hyperplasia | [84] |

| Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Anthocyanin extracted from black soybean | 50 mg/kg of anthocyanin extracted from black soybean twice a day for 2 weeks | Showed the anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects, as well as the synergistic effect with ciprofloxacin in chronic bacterial prostatitis | [85] | |

| 16-week-old Sprague Dawley male rats | Seoritae extract including isoflavone and anthocyanin | 228 and 457 mg/kg of seoritae extract in 1 mL distilled water daily for 5 weeks | Reduced the prostate weight, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and 5α-reductase activity | [86] | |

| 6-week-old male BALB/c nude mice | Anthocyanin from black soybean | 8 mg/kg of anthocyanin dissolved in 1 mL of distilled water daily for 14 weeks | Inhibited the progression of prostate cancer in a xenograft model. | [87] | |

| 8-week-old male Sprague–Dawley rats | Standard laboratory diet | Polymerized anthocyanin from grape skin | 100 mg/kg of polymerized anthocyanin from polymerized anthocyanin daily for 4 weeks | Reduced the prostate weight in rats with testosterone propionate–induced BPH, decreased the AR, 5AR2, SRC1, PSA, PCNA, and cyclin D1 expression in prostate tissues, ameliorated the BPH-mediated increase of Bcl-2 expression, and increased the Bax expression. | [88] |

| 7-week-old male Wistar rats | A diet ad libitum | Aronia melanocarpa containing C3G and cyanidin-3-xylose | 100 mg/kg of Aronia melanocarpa extract daily for 6 weeks | Attenuated the development of testosterone-induced prostatic hyperplasia | [89] |

| Male FVB mice | Standard diet | Brazilian berry extract (Myrciaria jaboticaba) | 2.9 and 5.8 g/kg of jaboticaba peel extract daily for 60 days | Exerted a dose-dependent effect controlling inflammation and oxidative-stress in aging and high-fat diet-fed aging mice prostate | [90] |

| Male heterozygous TRAP rats | A diet ad libitum | Anthocyanin-rich fraction from purple rice | 0.2 or 1% of hexane insoluble fraction from a purple rice ethanolic extract daily for 10 weeks | Retarded carcinogenesis and castration-resistant cancer growth of prostate through suppression of androgen receptor mediated cell proliferation and metabolism | [60] |

| Population | Number of Populations + Age Range | Study Type | Diet | Source of Anthocyanin | Anthocyanin Daily Dose | Association between Anthocyanin Intake and CRC Risk | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients newly diagnosed with resectable prostate cancer | 56 men/average age: 61.6 ± 1.02 years | Interventional | n.d | Nectar of BRB | 10 g BRB/day (8 men): 10 g BRB in 1 bottle (total: 320 bottle) | n.a | [93] |

| Nectar of BRB | 20 g BRB/day (8 men): 20 g BRB in 1 bottle (total: 320 bottle) | ||||||

| Confection of BRB | 10 g BRB/day (8 men): 10 g BRB in 5 pieces (total: 1600 pieces) | ||||||

| Confection of BRB | 20 g BRB/day (8 men): 20 g BRB in 10 pieces (total: 3200 pieces) | ||||||

| Patients receiving image guided intensity modulated radiation therapy to their prostate, prostate and regional lymph nodes or prostate bed were included | 41 men/average age: 68 years | Observational | Mostly New Zealand European | cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpo) capsules | 1 capsule/day at breakfast during radiation therapy treatment, and for 2 weeks post-treatment (9 weeks for prostate bed, 10 weeks for prostate and prostate nodes) | 65% of patients taking cranberry capsules developed cystitis compared to the placebo group (90% patients) | [94] |

| 30% of patients taking cranberry capsules Developed severe cystitis compared to the placebo group (45% patients) None of them developed urinary tract infections | |||||||

| Patients receiving external beam radiation therapy to their prostate bed or prostate only and had not received previous pelvic radiation therapy | 101 men/average age: 68 years (range 51–85) | Observational | Mostly New Zealand European | cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpo) capsules | 2 capsules at breakfast during radiation therapy treatment, For 2 weeks after | Three measurements of cystitis severity: modified RTOG, O’Leary interstitial cystitis scale, RICAS. No significant differences were observed between cranberry treated and placebo groups | [95] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mottaghipisheh, J.; Doustimotlagh, A.H.; Irajie, C.; Tanideh, N.; Barzegar, A.; Iraji, A. The Promising Therapeutic and Preventive Properties of Anthocyanidins/Anthocyanins on Prostate Cancer. Cells 2022, 11, 1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11071070

Mottaghipisheh J, Doustimotlagh AH, Irajie C, Tanideh N, Barzegar A, Iraji A. The Promising Therapeutic and Preventive Properties of Anthocyanidins/Anthocyanins on Prostate Cancer. Cells. 2022; 11(7):1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11071070

Chicago/Turabian StyleMottaghipisheh, Javad, Amir Hossein Doustimotlagh, Cambyz Irajie, Nader Tanideh, Alireza Barzegar, and Aida Iraji. 2022. "The Promising Therapeutic and Preventive Properties of Anthocyanidins/Anthocyanins on Prostate Cancer" Cells 11, no. 7: 1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11071070

APA StyleMottaghipisheh, J., Doustimotlagh, A. H., Irajie, C., Tanideh, N., Barzegar, A., & Iraji, A. (2022). The Promising Therapeutic and Preventive Properties of Anthocyanidins/Anthocyanins on Prostate Cancer. Cells, 11(7), 1070. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11071070