Current Therapeutic Options and Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Alcoholic Liver Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

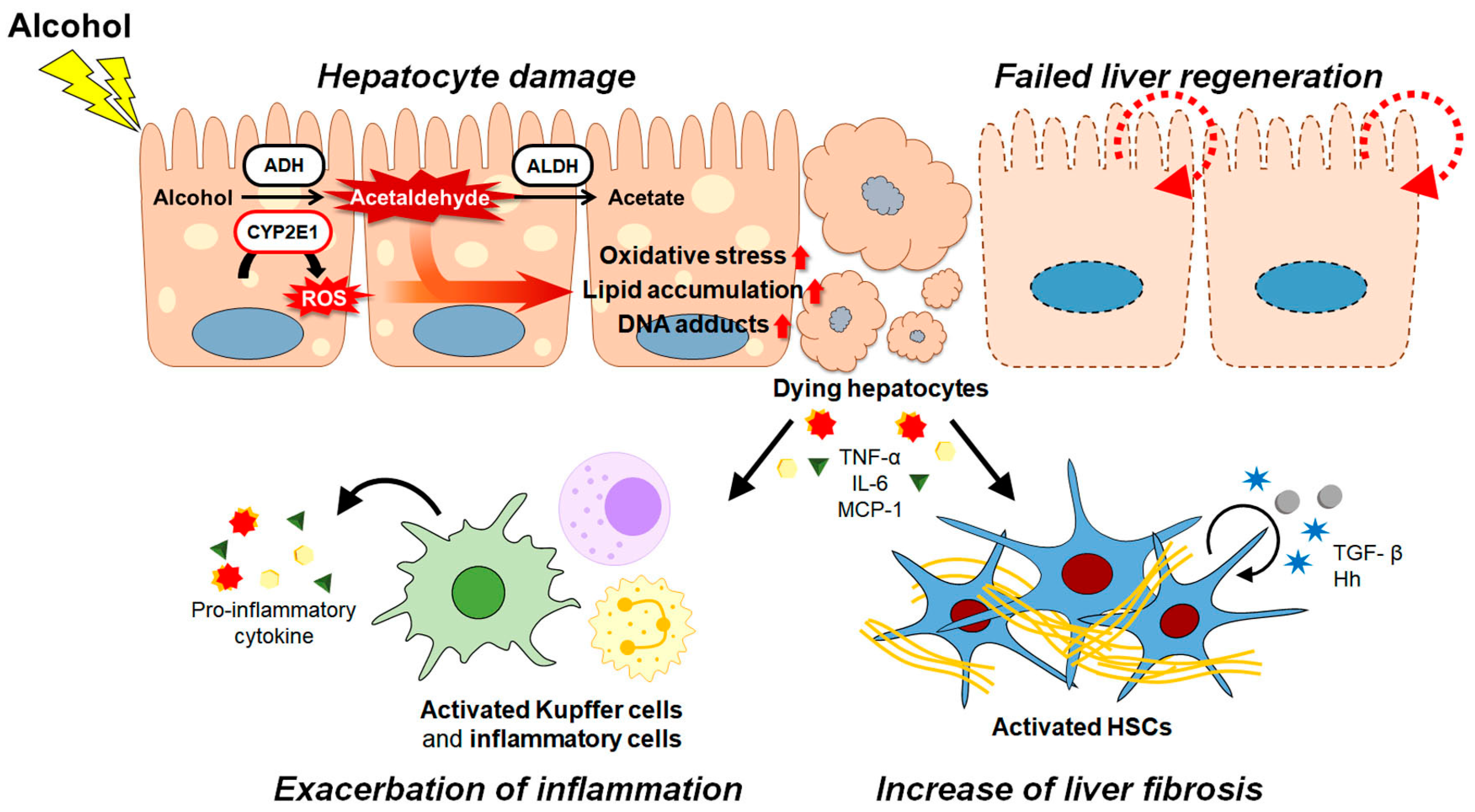

2. Pathogenesis of ALD

3. Current Therapies and New Targets for ALD

3.1. Management of Alcohol Abuse

3.2. Antioxidants Alleviating Oxidative Stress in ALD

3.3. Promoting Successful Liver Regeneration in ALD

3.4. Strategies to Relieve Inflammation in ALD

4. Stem Cell Therapy for ALD

4.1. Direct Transplantation of MSCs in ALD Treatment

4.2. Potential of Cell-Free Strategies for ALD Treatment

5. Limitations of Stem Cells Including MSCs Therapy

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rehm, J. The risks associated with alcohol use and alcoholism. Alcohol Res. Health 2011, 34, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Shield, K.D.; Parry, C.; Rehm, J. Chronic diseases and conditions related to alcohol use. Alcohol Res. 2013, 35, 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm, J.; Shield, K.D. Global Burden of Disease and the Impact of Mental and Addictive Disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.F.; Heilig, M.; Perez, A.; Probst, C.; Rehm, J. Alcohol use disorders. Lancet 2019, 394, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, J.; Shield, K.D. Global Burden of Alcohol Use Disorders and Alcohol Liver Disease. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rehm, J.; Samokhvalov, A.V.; Shield, K.D. Global burden of alcoholic liver diseases. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramkissoon, R.; Shah, V.H. Alcohol Use Disorder and Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease. Alcohol Res. 2022, 42, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J.; Han, J.; Lee, C.; Yoon, M.; Jung, Y. Pathophysiological Aspects of Alcohol Metabolism in the Liver. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederbaum, A.I. Alcohol metabolism. Clin. Liver Dis. 2012, 16, 667–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lieber, C.S. Ethanol metabolism, cirrhosis and alcoholism. Clin. Chim. Acta 1997, 257, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osna, N.A.; Donohue, T.M., Jr.; Kharbanda, K.K. Alcoholic Liver Disease: Pathogenesis and Current Management. Alcohol Res. 2017, 38, 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Byun, J.S.; Jeong, W.I. Involvement of hepatic innate immunity in alcoholic liver disease. Immune Netw. 2010, 10, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chacko, K.R.; Reinus, J. Spectrum of Alcoholic Liver Disease. Clin. Liver Dis. 2016, 20, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkiewitz, K.; Litten, R.Z.; Leggio, L. Advances in the science and treatment of alcohol use disorder. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deutsch-Link, S.; Curtis, B.; Singal, A.K. COVID-19 and alcohol associated liver disease. Dig. Liver Dis. 2022, 54, 1459–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuittonet, C.L.; Halse, M.; Leggio, L.; Fricchione, S.B.; Brickley, M.; Haass-Koffler, C.L.; Tavares, T.; Swift, R.M.; Kenna, G.A. Pharmacotherapy for alcoholic patients with alcoholic liver disease. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2014, 71, 1265–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, M.; Chang, B.; Mathews, S.; Gao, B. New drug targets for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatol. Int. 2014, 8, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, M.C.; Kerr, T.; Herlong, H.F. Current Management and Future Treatment of Alcoholic Hepatitis. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 16, 178–189. [Google Scholar]

- Singal, A.K.; Mathurin, P. Diagnosis and Treatment of Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease: A Review. JAMA 2021, 326, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Bataller, R. Alcoholic liver disease: Pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1572–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kong, L.Z.; Chandimali, N.; Han, Y.H.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, S.U.; Kim, T.D.; Jeong, D.K.; Sun, H.N.; Lee, D.S.; et al. Pathogenesis, Early Diagnosis, and Therapeutic Management of Alcoholic Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, X.; Meng, Y.; Han, Z.; Ye, F.; Wei, L.; Zong, C. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for liver disease: Full of chances and challenges. Cell Biosci. 2020, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, C.; Wang, Y.; Luebke-Wheeler, J.; Nyberg, S.L. Stem Cell Therapies for Treatment of Liver Disease. Biomedicines 2016, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Sun, M.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Li, M. Stem Cell-Based Therapies for Liver Diseases: An Overview and Update. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 16, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.H.; Kim, M.Y.; Eom, Y.W.; Baik, S.K. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for the Treatment of Liver Disease: Present and Perspectives. Gut Liver 2020, 14, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Li, L. The Application of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Treatment of Liver Diseases: Mechanism, Efficacy, and Safety Issues. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 655268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Bao, Q.; Li, L. Mesenchymal stem cell-based cell-free strategies: Safe and effective treatments for liver injury. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.C.; Shyu, W.C.; Lin, S.Z. Mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Transplant. 2011, 20, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Volarevic, V.; Markovic, B.S.; Gazdic, M.; Volarevic, A.; Jovicic, N.; Arsenijevic, N.; Armstrong, L.; Djonov, V.; Lako, M.; Stojkovic, M. Ethical and Safety Issues of Stem Cell-Based Therapy. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 15, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, C.; Kim, M.; Han, J.; Yoon, M.; Jung, Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Influence Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells, and Constitute a Promising Therapy for Liver Fibrosis. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holford, N.H. Clinical pharmacokinetics of ethanol. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1987, 13, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louvet, A.; Mathurin, P. Alcoholic liver disease: Mechanisms of injury and targeted treatment. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Cederbaum, A.I. CYP2E1 and oxidative liver injury by alcohol. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 723–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leung, T.M.; Nieto, N. CYP2E1 and oxidant stress in alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2013, 58, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieber, M.; Chandel, N.S. ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R453–R462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Migdal, C.; Serres, M. Reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress. Med. Sci. 2011, 27, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichoż-Lach, H.; Michalak, A. Oxidative stress as a crucial factor in liver diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 8082–8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Carr, R. Alcohol effects on hepatic lipid metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2020, 61, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baraona, E.; Lieber, C.S. Effects of ethanol on lipid metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 1979, 20, 289–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.K.; Yates, E.; Lilly, K.; Dhanda, A.D. Oxidative stress in alcohol-related liver disease. World J. Hepatol. 2020, 12, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Cederbaum, A.I. Alcohol and oxidative liver injury. Hepatology 2006, 43, S63–S74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Cederbaum, A.I. Alcohol, oxidative stress, and free radical damage. Alcohol Res. Health 2003, 27, 277–284. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Zhai, Q.; Shi, X. Alcohol-induced oxidative stress and cell responses. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 21, S26–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsermpini, E.E.; Plemenitaš Ilješ, A.; Dolžan, V. Alcohol-Induced Oxidative Stress and the Role of Antioxidants in Alcohol Use Disorder: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, J.B.; Cahill, A.; Pastorino, J.G. Alcohol and mitochondria: A dysfunctional relationship. Gastroenterology 2002, 122, 2049–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantena, S.K.; King, A.L.; Andringa, K.K.; Eccleston, H.B.; Bailey, S.M. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of alcohol- and obesity-induced fatty liver diseases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 1259–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abdallah, M.A.; Singal, A.K. Mitochondrial dysfunction and alcohol-associated liver disease: A novel pathway and therapeutic target. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lv, Y.; So, K.F.; Xiao, J. Liver regeneration and alcoholic liver disease. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, A.M. Recent events in alcoholic liver disease V. effects of ethanol on liver regeneration. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2005, 288, G1–G6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michalopoulos, G.K.; Bhushan, B. Liver regeneration: Biological and pathological mechanisms and implications. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiseleva, Y.V.; Antonyan, S.Z.; Zharikova, T.S.; Tupikin, K.A.; Kalinin, D.V.; Zharikov, Y.O. Molecular pathways of liver regeneration: A comprehensive review. World J. Hepatol. 2021, 13, 270–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horiguchi, N.; Ishac, E.J.; Gao, B. Liver regeneration is suppressed in alcoholic cirrhosis: Correlation with decreased STAT3 activation. Alcohol 2007, 41, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duguay, L.; Coutu, D.; Hetu, C.; Joly, J.G. Inhibition of liver regeneration by chronic alcohol administration. Gut 1982, 23, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kawaratani, H.; Tsujimoto, T.; Douhara, A.; Takaya, H.; Moriya, K.; Namisaki, T.; Noguchi, R.; Yoshiji, H.; Fujimoto, M.; Fukui, H. The effect of inflammatory cytokines in alcoholic liver disease. Mediat. Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 495156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, M.G. Cytokines—Central factors in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Res. Health 2003, 27, 307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, T.; Zhang, C.L.; Xiao, M.; Yang, R.; Xie, K.Q. Critical Roles of Kupffer Cells in the Pathogenesis of Alcoholic Liver Disease: From Basic Science to Clinical Trials. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiguchi, N.; Wang, L.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Park, O.; Jeong, W.I.; Lafdil, F.; Osei-Hyiaman, D.; Moh, A.; Fu, X.Y.; Pacher, P.; et al. Cell type-dependent pro- and anti-inflammatory role of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 in alcoholic liver injury. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nowak, A.J.; Relja, B. The Impact of Acute or Chronic Alcohol Intake on the NF-κB Signaling Pathway in Alcohol-Related Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, Y.; Brenner, D.A. Liver inflammation and fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, E.; Schwabe, R.F. Hepatic inflammation and fibrosis: Functional links and key pathways. Hepatology 2015, 61, 1066–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brenner, D.A. Molecular pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 2009, 120, 361–368. [Google Scholar]

- Dhar, D.; Baglieri, J.; Kisseleva, T.; Brenner, D.A. Mechanisms of liver fibrosis and its role in liver cancer. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020, 245, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, U.E.; Friedman, S.L. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2011, 25, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, T.; Friedman, S.L.; Hoshida, Y. Hepatic stellate cells as key target in liver fibrosis. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 2017, 121, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Brown, K.D.; Witek, R.P.; Omenetti, A.; Yang, L.; Vandongen, M.; Milton, R.J.; Hines, I.N.; Rippe, R.A.; Spahr, L.; et al. Accumulation of hedgehog-responsive progenitors parallels alcoholic liver disease severity in mice and humans. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 1532–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kurys-Denis, E.; Prystupa, A.; Luchowska-Kocot, D.; Krupski, W.; Bis-Wencel, H.; Panasiuk, L. PDGF-BB homodimer serum level—A good indicator of the severity of alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2020, 27, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flisiak, R.; Pytel-Krolczuk, B.; Prokopowicz, D. Circulating transforming growth factor β1 as an indicator of hepatic function impairment in liver cirrhosis. Cytokine 2000, 12, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, A.C.; Ilangovan, N.; Rajma, J. Risk factors for alcohol use relapse after abstinence in patients with alcoholic liver disease. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 5995–5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrill, C.; Markham, H.; Templeton, A.; Carr, N.J.; Sheron, N. Alcohol-related cirrhosis—Early abstinence is a key factor in prognosis, even in the most severe cases. Addiction 2009, 104, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggio, L.; Lee, M.R. Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder in Patients with Alcoholic Liver Disease. Am. J. Med. 2017, 130, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arab, J.P.; Izzy, M.; Leggio, L.; Bataller, R.; Shah, V.H. Management of alcohol use disorder in patients with cirrhosis in the setting of liver transplantation. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, R.M.; Aston, E.R. Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder: Current and emerging therapies. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry. 2015, 23, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Crowley, P. Long-term drug treatment of patients with alcohol dependence. Aust. Prescr. 2015, 38, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Anton, R.F. Naltrexone for the management of alcohol dependence. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lobmaier, P.P.; Kunøe, N.; Gossop, M.; Waal, H. Naltrexone depot formulations for opioid and alcohol dependence: A systematic review. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2011, 17, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Beaurepaire, R. A Review of the Potential Mechanisms of Action of Baclofen in Alcohol Use Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mason, B.J.; Heyser, C.J. Acamprosate: A prototypic neuromodulator in the treatment of alcohol dependence. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2010, 9, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutschler, J.; Grosshans, M.; Soyka, M.; Rösner, S. Current Findings and Mechanisms of Action of Disulfiram in the Treatment of Alcohol Dependence. Pharmacopsychiatry 2016, 49, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haass-Koffler, C.L.; Akhlaghi, F.; Swift, R.M.; Leggio, L. Altering ethanol pharmacokinetics to treat alcohol use disorder: Can you teach an old dog new tricks? J. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 31, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yen, M.H.; Ko, H.C.; Tang, F.I.; Lu, R.B.; Hong, J.S. Study of hepatotoxicity of naltrexone in the treatment of alcoholism. Alcohol 2006, 38, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramer, L.; Tihy, M.; Goossens, N.; Frossard, J.L.; Rubbia-Brandt, L.; Spahr, L. Disulfiram-Induced Acute Liver Injury. Case Rep. Hepatol. 2020, 2020, 8835647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parés, A.; Caballería, J.; Bruguera, M.; Torres, M.; Rodés, J. Histological course of alcoholic hepatitis. Influence of abstinence, sex and extent of hepatic damage. J. Hepatol. 1986, 2, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, T.I.; Orholm, M.; Bentsen, K.D.; Høybye, G.; Eghøje, K.; Christoffersen, P. Prospective evaluation of alcohol abuse and alcoholic liver injury in men as predictors of development of cirrhosis. Lancet 1984, 2, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteel, G.E. Oxidants and antioxidants in alcohol-induced liver disease. Gastroenterology 2003, 124, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sid, B.; Verrax, J.; Calderon, P.B. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of alcohol-induced liver disease. Free Radic. Res. 2013, 47, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thursz, M.; Morgan, T.R. Treatment of Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1823–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kurutas, E.B. The importance of antioxidants which play the role in cellular response against oxidative/nitrosative stress: Current state. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Herbay, A.; de Groot, H.; Hegi, U.; Stremmel, W.; Strohmeyer, G.; Sies, H. Low vitamin E content in plasma of patients with alcoholic liver disease, hemochromatosis and Wilson’s disease. J. Hepatol. 1994, 20, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, M.A.; Rosman, A.S.; Lieber, C.S. Differential depletion of carotenoids and tocopherol in liver disease. Hepatology 1993, 17, 977–986. [Google Scholar]

- Masalkar, P.D.; Abhang, S.A. Oxidative stress and antioxidant status in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Clin. Chim. Acta 2005, 355, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Huang, J.; Luo, Z.; Jiang, M.; Lu, Y.; Lin, Q.; Liu, H.; Cheng, N.; et al. Endoplasmic reticulum-targeted inhibition of CYP2E1 with vitamin E nanoemulsions alleviates hepatocyte oxidative stress and reverses alcoholic liver disease. Biomaterials 2022, 288, 121720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, J.; Shalini, S.; Bansal, M.P. Influence of vitamin E on alcohol-induced changes in antioxidant defenses in mice liver. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2010, 20, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altavilla, D.; Marini, H.; Seminara, P.; Squadrito, G.; Minutoli, L.; Passaniti, M.; Bitto, A.; Calapai, G.; Calò, M.; Caputi, A.P.; et al. Protective effects of antioxidant raxofelast in alcohol-induced liver disease in mice. Pharmacology 2005, 74, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Maza, M.P.; Petermann, M.; Bunout, D.; Hirsch, S. Effects of long-term vitamin E supplementation in alcoholic cirrhotics. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1995, 14, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezey, E.; Potter, J.J.; Rennie-Tankersley, L.; Caballeria, J.; Pares, A. A randomized placebo controlled trial of vitamin E for alcoholic hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2004, 40, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashima, Y.; Shibata, M.; Honma, Y.; Matsuoka, H.; Hiura, M.; Abe, S.; Harada, M. Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis Effectively Treated with Vitamin E as an Add-on to Corticosteroids. Intern. Med. 2017, 56, 3293–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atkuri, K.R.; Mantovani, J.J.; Herzenberg, L.A.; Herzenberg, L.A. N-Acetylcysteine—A safe antidote for cysteine/glutathione deficiency. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2007, 7, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lebourgeois, S.; González-Marín, M.C.; Antol, J.; Naassila, M.; Vilpoux, C. Evaluation of N-acetylcysteine on ethanol self-administration in ethanol-dependent rats. Neuropharmacology 2019, 150, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebourgeois, S.; González-Marín, M.C.; Jeanblanc, J.; Naassila, M.; Vilpoux, C. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on motivation, seeking and relapse to ethanol self-administration. Addict. Biol. 2018, 23, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squeglia, L.M.; Tomko, R.L.; Baker, N.L.; McClure, E.A.; Book, G.A.; Gray, K.M. The effect of N-acetylcysteine on alcohol use during a cannabis cessation trial. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2018, 185, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshbaten, M.; Aliasgarzadeh, A.; Masnadi, K.; Tarzamani, M.K.; Farhang, S.; Babaei, H.; Kiani, J.; Zaare, M.; Najafipoor, F. N-acetylcysteine improves liver function in patients with non-alcoholic Fatty liver disease. Hepat. Mon. 2010, 10, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nabi, T.; Nabi, S.; Rafiq, N.; Shah, A. Role of N-acetylcysteine treatment in non-acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure: A prospective study. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walayat, S.; Shoaib, H.; Asghar, M.; Kim, M.; Dhillon, S. Role of N-acetylcysteine in non-acetaminophen-related acute liver failure: An updated meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2021, 34, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, K.C.; Baillie, A.; Van Den Brink, W.; Chitty, K.E.; Brady, K.; Back, S.E.; Seth, D.; Sutherland, G.; Leggio, L.; Haber, P.S. N-acetyl cysteine in the treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with liver disease: Rationale for further research. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2018, 27, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaras, R.; Tahan, V.; Aydin, S.; Uzun, H.; Kaya, S.; Senturk, H. N-acetylcysteine attenuates alcohol-induced oxidative stress in the rat. World J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 9, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Checa, J.C.; Hirano, T.; Tsukamoto, H.; Kaplowitz, N. Mitochondrial glutathione depletion in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol 1993, 10, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, H.; Lu, S.C. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver injury. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 1335–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lauterburg, B.H.; Velez, M.E. Glutathione deficiency in alcoholics: Risk factor for paracetamol hepatotoxicity. Gut 1988, 29, 1153–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ronis, M.J.; Butura, A.; Sampey, B.P.; Shankar, K.; Prior, R.L.; Korourian, S.; Albano, E.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M.; Petersen, D.R.; Badger, T.M. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity in rats fed via total enteral nutrition. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005, 39, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Khac, E.; Thevenot, T.; Piquet, M.A.; Benferhat, S.; Goria, O.; Chatelain, D.; Tramier, B.; Dewaele, F.; Ghrib, S.; Rudler, M.; et al. Glucocorticoids plus N-acetylcysteine in severe alcoholic hepatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1781–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stewart, S.; Prince, M.; Bassendine, M.; Hudson, M.; James, O.; Jones, D.; Record, C.; Day, C.P. A randomized trial of antioxidant therapy alone or with corticosteroids in acute alcoholic hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2007, 47, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Keisham, A.; Bhalla, A.; Sharma, N.; Agarwal, R.; Sharma, R.; Singh, A. Efficacy of Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor and N-Acetylcysteine Therapies in Patients With Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 1650–1656.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stoops, W.W.; Strickland, J.C.; Hays, L.R.; Rayapati, A.O.; Lile, J.A.; Rush, C.R. Influence of n-acetylcysteine maintenance on the pharmacodynamic effects of oral ethanol. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2020, 198, 173037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.C.; Mato, J.M. S-adenosylmethionine in liver health, injury, and cancer. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 1515–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.L.; Chen, L.J.; Bair, M.J.; Yao, M.L.; Peng, H.C.; Yang, S.S.; Yang, S.C. Antioxidative status of patients with alcoholic liver disease in southeastern Taiwan. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duce, A.M.; Ortíz, P.; Cabrero, C.; Mato, J.M. S-adenosyl-L-methionine synthetase and phospholipid methyltransferase are inhibited in human cirrhosis. Hepatology 1988, 8, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederbaum, A.I. Hepatoprotective effects of S-adenosyl-L-methionine against alcohol- and cytochrome P450 2E1-induced liver injury. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 1366–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieber, C.S.; Casini, A.; DeCarli, L.M.; Kim, C.I.; Lowe, N.; Sasaki, R.; Leo, M.A. S-adenosyl-L-methionine attenuates alcohol-induced liver injury in the baboon. Hepatology 1990, 11, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaldi, A.; Gluud, C. S-adenosyl-L-methionine for alcoholic liver diseases. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006, Cd002235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anstee, Q.M.; Day, C.P. S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) therapy in liver disease: A review of current evidence and clinical utility. J. Hepatol. 2012, 57, 1097–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stickel, F.; Datz, C.; Hampe, J.; Bataller, R. Pathophysiology and Management of Alcoholic Liver Disease: Update 2016. Gut Liver 2017, 11, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, K.H.; Hashimoto, N.; Fukushima, M. Relationships among alcoholic liver disease, antioxidants, and antioxidant enzymes. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singal, A.K.; Jampana, S.C.; Weinman, S.A. Antioxidants as therapeutic agents for liver disease. Liver Int. 2011, 31, 1432–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jadeja, R.N.; Devkar, R.V.; Nammi, S. Oxidative Stress in Liver Diseases: Pathogenesis, Prevention, and Therapeutics. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 8341286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, B.G.; Henderson, G.I.; Frosto, T.A.; Schenker, S. Effect of ethanol on rat fetal hepatocytes: Studies on cell replication, lipid peroxidation and glutathione. Hepatology 1993, 18, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berasain, C.; Arechederra, M.; Argemí, J.; Fernández-Barrena, M.G.; Avila, M.A. Loss of liver function in chronic liver disease: An identity crisis. J. Hepatol. 2022, in press. [CrossRef]

- Deotare, U.; Al-Dawsari, G.; Couban, S.; Lipton, J.H. G-CSF-primed bone marrow as a source of stem cells for allografting: Revisiting the concept. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2015, 50, 1150–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spahr, L.; Lambert, J.F.; Rubbia-Brandt, L.; Chalandon, Y.; Frossard, J.L.; Giostra, E.; Hadengue, A. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor induces proliferation of hepatic progenitors in alcoholic steatohepatitis: A randomized trial. Hepatology 2008, 48, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Sharma, A.K.; Narasimhan, R.L.; Bhalla, A.; Sharma, N.; Sharma, R. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in severe alcoholic hepatitis: A randomized pilot study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 1417–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Park, Y.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, W.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, D.J. Efficacy of granulocyte colony stimulating factor in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis with partial or null response to steroid (GRACIAH trial): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2018, 19, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baig, M.; Walayat, S.; Dhillon, S.; Puli, S. Efficacy of Granulocyte Colony Stimulating Factor in Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2020, 12, e10474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, C.X.; Tang, J.; Wang, X.Y.; Wu, F.R.; Ge, J.F.; Chen, F.H. Role of interleukin-22 in liver diseases. Inflamm. Res. 2014, 63, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, Y.; Min, J.; Ge, C.; Shu, J.; Tian, D.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, D. Interleukin 22 in Liver Injury, Inflammation and Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 2405–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, T.; Ishihara, K.; Hibi, M. Roles of STAT3 in mediating the cell growth, differentiation and survival signals relayed through the IL-6 family of cytokine receptors. Oncogene 2000, 19, 2548–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radaeva, S.; Sun, R.; Pan, H.N.; Hong, F.; Gao, B. Interleukin 22 (IL-22) plays a protective role in T cell-mediated murine hepatitis: IL-22 is a survival factor for hepatocytes via STAT3 activation. Hepatology 2004, 39, 1332–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Hu, B.; Colletti, L.M. IL-22 is involved in liver regeneration after hepatectomy. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010, 298, G74–G80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arab, J.P.; Sehrawat, T.S.; Simonetto, D.A.; Verma, V.K.; Feng, D.; Tang, T.; Dreyer, K.; Yan, X.; Daley, W.L.; Sanyal, A.; et al. An Open-Label, Dose-Escalation Study to Assess the Safety and Efficacy of IL-22 Agonist F-652 in Patients with Alcohol-associated Hepatitis. Hepatology 2020, 72, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cobleigh, M.A.; Lian, J.Q.; Huang, C.X.; Booth, C.J.; Bai, X.F.; Robek, M.D. A proinflammatory role for interleukin-22 in the immune response to hepatitis B virus. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1897–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abassa, K.K.; Wu, X.Y.; Xiao, X.P.; Zhou, H.X.; Guo, Y.W.; Wu, B. Effect of alcohol on clinical complications of hepatitis virus-induced liver cirrhosis: A consecutive ten-year study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Ahmad, M.F.; Nagy, L.E.; Tsukamoto, H. Inflammatory pathways in alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, M.J.; Zhou, Z.; Parker, R.; Gao, B. Targeting inflammation for the treatment of alcoholic liver disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 180, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, P.; Pritchard, M.T.; Nagy, L.E. Anti-inflammatory pathways and alcoholic liver disease: Role of an adiponectin/interleukin-10/heme oxygenase-1 pathway. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 1330–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaratani, H.; Moriya, K.; Namisaki, T.; Uejima, M.; Kitade, M.; Takeda, K.; Okura, Y.; Kaji, K.; Takaya, H.; Nishimura, N.; et al. Therapeutic strategies for alcoholic liver disease: Focusing on inflammation and fibrosis (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 40, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smart, L.; Gobejishvili, L.; Crittenden, N.; Barve, S.; McClain, C.J. Alcoholic Hepatitis: Steroids vs. Pentoxifylline. Curr. Hepatol. Rep. 2013, 12, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saberi, B.; Dadabhai, A.S.; Jang, Y.Y.; Gurakar, A.; Mezey, E. Current Management of Alcoholic Hepatitis and Future Therapies. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2016, 4, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spahr, L.; Rubbia-Brandt, L.; Pugin, J.; Giostra, E.; Frossard, J.L.; Borisch, B.; Hadengue, A. Rapid changes in alcoholic hepatitis histology under steroids: Correlation with soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in hepatic venous blood. J. Hepatol. 2001, 35, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taïeb, J.; Mathurin, P.; Elbim, C.; Cluzel, P.; Arce-Vicioso, M.; Bernard, B.; Opolon, P.; Gougerot-Pocidalo, M.A.; Poynard, T.; Chollet-Martin, S. Blood neutrophil functions and cytokine release in severe alcoholic hepatitis: Effect of corticosteroids. J. Hepatol. 2000, 32, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddrey, W.C.; Boitnott, J.K.; Bedine, M.S.; Weber, F.L., Jr.; Mezey, E.; White, R.I., Jr. Corticosteroid therapy of alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 1978, 75, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louvet, A.; Thursz, M.R.; Kim, D.J.; Labreuche, J.; Atkinson, S.R.; Sidhu, S.S.; O’Grady, J.G.; Akriviadis, E.; Sinakos, E.; Carithers, R.L., Jr.; et al. Corticosteroids Reduce Risk of Death within 28 Days for Patients with Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis, Compared with Pentoxifylline or Placebo-a Meta-analysis of Individual Data From Controlled Trials. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 458–468.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, A.K.; Walia, I.; Singal, A.; Soloway, R.D. Corticosteroids and pentoxifylline for the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis: Current status. World J. Hepatol. 2011, 3, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Louvet, A.; Diaz, E.; Dharancy, S.; Coevoet, H.; Texier, F.; Thévenot, T.; Deltenre, P.; Canva, V.; Plane, C.; Mathurin, P. Early switch to pentoxifylline in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis is inefficient in non-responders to corticosteroids. J. Hepatol. 2008, 48, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assimakopoulos, S.F.; Thomopoulos, K.C.; Labropoulou-Karatza, C. Pentoxifylline: A first line treatment option for severe alcoholic hepatitis and hepatorenal syndrome? World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 3194–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, M.; Wheeler, M.D.; Kono, H.; Bradford, B.U.; Gallucci, R.M.; Luster, M.I.; Thurman, R.G. Essential role of tumor necrosis factor alpha in alcohol-induced liver injury in mice. Gastroenterology 1999, 117, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akriviadis, E.; Botla, R.; Briggs, W.; Han, S.; Reynolds, T.; Shakil, O. Pentoxifylline improves short-term survival in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2000, 119, 1637–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Parker, R.; Armstrong, M.J.; Corbett, C.; Rowe, I.A.; Houlihan, D.D. Systematic review: Pentoxifylline for the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 37, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whitfield, K.; Rambaldi, A.; Wetterslev, J.; Gluud, C. Pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 2009, Cd007339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClain, C.J.; Barve, S.; Barve, S.; Deaciuc, I.; Hill, D.B. Tumor necrosis factor and alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1998, 22, 248s–252s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iimuro, Y.; Gallucci, R.M.; Luster, M.I.; Kono, H.; Thurman, R.G. Antibodies to tumor necrosis factor alfa attenuate hepatic necrosis and inflammation caused by chronic exposure to ethanol in the rat. Hepatology 1997, 26, 1530–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, C.; Nanchahal, J.; Taylor, P.; Feldmann, M. Anti-TNF therapy: Past, present and future. Int. Immunol. 2015, 27, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.B.; Agrawal, R.; Attar, B.M.; Abu Omar, Y.; Gandhi, S.R. Safety and Efficacy of Infliximab in Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2019, 11, e5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonnel, A.R.; Bunchorntavakul, C.; Reddy, K.R. Immune dysfunction and infections in patients with cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 9, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunchorntavakul, C.; Chavalitdhamrong, D. Bacterial infections other than spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis. World J. Hepatol. 2012, 4, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naveau, S.; Chollet-Martin, S.; Dharancy, S.; Mathurin, P.; Jouet, P.; Piquet, M.A.; Davion, T.; Oberti, F.; Broët, P.; Emilie, D. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of infliximab associated with prednisolone in acute alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 2004, 39, 1390–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathews, S.; Gao, B. Therapeutic potential of interleukin 1 inhibitors in the treatment of alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 2013, 57, 2078–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tilg, H.; Moschen, A.R.; Szabo, G. Interleukin-1 and inflammasomes in alcoholic liver disease/acute alcoholic hepatitis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2016, 64, 955–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barbier, L.; Ferhat, M.; Salamé, E.; Robin, A.; Herbelin, A.; Gombert, J.M.; Silvain, C.; Barbarin, A. Interleukin-1 Family Cytokines: Keystones in Liver Inflammatory Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrasek, J.; Bala, S.; Csak, T.; Lippai, D.; Kodys, K.; Menashy, V.; Barrieau, M.; Min, S.Y.; Kurt-Jones, E.A.; Szabo, G. IL-1 receptor antagonist ameliorates inflammasome-dependent alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 3476–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tilg, H.; Wilmer, A.; Vogel, W.; Herold, M.; Nölchen, B.; Judmaier, G.; Huber, C. Serum levels of cytokines in chronic liver diseases. Gastroenterology 1992, 103, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Castejon, G.; Brough, D. Understanding the mechanism of IL-1β secretion. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011, 22, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Kanneganti, T.D. Function and regulation of IL-1α in inflammatory diseases and cancer. Immunol. Rev. 2018, 281, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, G.; Mitchell, M.; McClain, C.J.; Dasarathy, S.; Barton, B.; McCullough, A.J.; Nagy, L.E.; Kroll-Desrosiers, A.; Tornai, D.; Min, H.A.; et al. IL-1 receptor antagonist plus pentoxifylline and zinc for severe alcohol-associated hepatitis. Hepatology 2022, 76, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergis, N.; Patel, V.; Bogdanowicz, K.; Czyzewska-Khan, J.; Fiorentino, F.; Day, E.; Cross, M.; Foster, N.; Lord, E.; Goldin, R.; et al. IL-1 Signal Inhibition In Alcoholic Hepatitis (ISAIAH): A study protocol for a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial to explore the potential benefits of canakinumab in the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis. Trials 2021, 22, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ćurčić, I.B.; Kizivat, T.; Petrović, A.; Smolić, R.; Tabll, A.; Wu, G.Y.; Smolić, M. Therapeutic Perspectives of IL1 Family Members in Liver Diseases: An Update. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2022, 10, 1186–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawar, M.B.; Azam, F.; Sheikh, N.; Abdul Mujeeb, K. How Does Interleukin-22 Mediate Liver Regeneration and Prevent Injury and Fibrosis? J. Immunol. Res. 2016, 2016, 2148129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ki, S.H.; Park, O.; Zheng, M.; Morales-Ibanez, O.; Kolls, J.K.; Bataller, R.; Gao, B. Interleukin-22 treatment ameliorates alcoholic liver injury in a murine model of chronic-binge ethanol feeding: Role of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. Hepatology 2010, 52, 1291–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, T.T.; Wang, Z.R.; Yao, W.Q.; Linghu, E.Q.; Wang, F.S.; Shi, L. Stem Cell Therapies for Chronic Liver Diseases: Progress and Challenges. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2022, 11, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Mao, Y.; Xie, Y.; Wei, J.; Yao, J. Stem cells for treatment of liver fibrosis/cirrhosis: Clinical progress and therapeutic potential. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallanna, S.K.; Duncan, S.A. Differentiation of hepatocytes from pluripotent stem cells. Curr. Protoc. Stem Cell Biol. 2013, 26, 1g.4.1–1g.4.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woo, D.H.; Kim, S.K.; Lim, H.J.; Heo, J.; Park, H.S.; Kang, G.Y.; Kim, S.E.; You, H.J.; Hoeppner, D.J.; Kim, Y.; et al. Direct and indirect contribution of human embryonic stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells to liver repair in mice. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamoto, Y.; Takayama, K.; Ohashi, K.; Okamoto, R.; Sakurai, F.; Tachibana, M.; Kawabata, K.; Mizuguchi, H. Transplantation of a human iPSC-derived hepatocyte sheet increases survival in mice with acute liver failure. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, Y.; Yang, J.; Fang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Candi, E.; Wang, J.; Hua, D.; Shao, C.; Shi, Y. The secretion profile of mesenchymal stem cells and potential applications in treating human diseases. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2022, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, K.; Shi, C.; Fan, B.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Ji, G. Bone marrow derived-mesenchymal stem cell improves diabetes-associated fatty liver via mitochondria transformation in mice. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Huang, B.; Miao, G.; Yan, X.; Gao, G.; Luo, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, W.; Yang, L. Mesenchymal stem cells reverse high-fat diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease through suppression of CD4+ T lymphocytes in mice. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 3769–3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rezabakhsh, A.; Sokullu, E.; Rahbarghazi, R. Applications, challenges and prospects of mesenchymal stem cell exosomes in regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, P.; McDaniel, K.; Francis, H.; Kennedy, L.; Alpini, G.; Meng, F. Molecular mechanisms of stem cell therapy in alcoholic liver disease. Dig. Liver Dis. 2014, 46, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezquer, F.; Bruna, F.; Calligaris, S.; Conget, P.; Ezquer, M. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells: A promising strategy to manage alcoholic liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Fu, Q.L. Mechanisms underlying the protective effects of mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 2771–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoang, D.M.; Pham, P.T.; Bach, T.Q.; Ngo, A.T.L.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Phan, T.T.K.; Nguyen, G.H.; Le, P.T.T.; Hoang, V.T.; Forsyth, N.R.; et al. Stem cell-based therapy for human diseases. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2022, 7, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, R.M. Current state of stem cell-based therapies: An overview. Stem Cell Investig. 2020, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaifi, M.; Eom, Y.W.; Newsome, P.N.; Baik, S.K. Mesenchymal stromal cell therapy for liver diseases. J. Hepatol. 2018, 68, 1272–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wan, Y.M.; Li, Z.Q.; Liu, C.; He, Y.F.; Wang, M.J.; Wu, X.N.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.H. Mesenchymal stem cells reduce alcoholic hepatitis in mice via suppression of hepatic neutrophil and macrophage infiltration, and of oxidative stress. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ge, L.; Chen, D.; Chen, W.; Cai, C.; Tao, Y.; Ye, S.; Lin, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Xu, L.; et al. Pre-activation of TLR3 enhances the therapeutic effect of BMMSCs through regulation the intestinal HIF-2α signaling pathway and balance of NKB cells in experimental alcoholic liver injury. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 70, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Lv, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Li, H.; Xiao, J. Co-stimulation of LPAR1 and S1PR1/3 increases the transplantation efficacy of human mesenchymal stem cells in drug-induced and alcoholic liver diseases. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Fan, L.; Zhang, F.; Li, L. The clinical application of mesenchymal stem cells in liver disease: The current situation and potential future. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, Y.O.; Kim, Y.J.; Baik, S.K.; Kim, M.Y.; Eom, Y.W.; Cho, M.Y.; Park, H.J.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, B.R.; Kim, J.W.; et al. Histological improvement following administration of autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for alcoholic cirrhosis: A pilot study. Liver Int. 2014, 34, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk, K.T.; Yoon, J.H.; Kim, M.Y.; Kim, C.W.; Kim, J.K.; Park, H.; Hwang, S.G.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, B.S.; Lee, S.H.; et al. Transplantation with autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for alcoholic cirrhosis: Phase 2 trial. Hepatology 2016, 64, 2185–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharaziha, P.; Hellström, P.M.; Noorinayer, B.; Farzaneh, F.; Aghajani, K.; Jafari, F.; Telkabadi, M.; Atashi, A.; Honardoost, M.; Zali, M.R.; et al. Improvement of liver function in liver cirrhosis patients after autologous mesenchymal stem cell injection: A phase I-II clinical trial. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 21, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Yuan, Z.; Weng, J.; Pei, D.; Du, X.; He, C.; Lai, P. Challenges and advances in clinical applications of mesenchymal stromal cells. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaram, R.; Subramani, B.; Abdullah, B.J.J.; Mahadeva, S. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for advanced liver cirrhosis: A case report. JGH Open 2017, 1, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahr, L.; Chalandon, Y.; Terraz, S.; Kindler, V.; Rubbia-Brandt, L.; Frossard, J.L.; Breguet, R.; Lanthier, N.; Farina, A.; Passweg, J.; et al. Autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation in patients with decompensated alcoholic liver disease: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikfarjam, S.; Rezaie, J.; Zolbanin, N.M.; Jafari, R. Mesenchymal stem cell derived-exosomes: A modern approach in translational medicine. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eleuteri, S.; Fierabracci, A. Insights into the Secretome of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Its Potential Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, S.; Lee, J.S.; Hyun, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.U.; Cha, H.J.; Jung, Y. Tumor necrosis factor-inducible gene 6 promotes liver regeneration in mice with acute liver injury. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2015, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, S.; Lee, C.; Kim, J.; Hyun, J.; Lim, M.; Cha, H.J.; Oh, S.H.; Choi, Y.H.; Jung, Y. Tumor necrosis factor-inducible gene 6 protein ameliorates chronic liver damage by promoting autophagy formation in mice. Exp. Mol. Med. 2017, 49, e380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, C.; Oh, D.; Han, J.; Kim, T.J.; Kim, S.W.; Seo, Y.S.; Oh, S.H.; Jung, Y. Tumor necrosis factor-inducible gene 6 reprograms hepatic stellate cells into stem-like cells, which ameliorates liver damage in mouse. Biomaterials 2019, 219, 119375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Y.M.; Li, Z.Q.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, C.; Wang, M.J.; Wu, H.X.; Mu, Y.Z.; He, Y.F.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.N.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells alleviate liver injury induced by chronic-binge ethanol feeding in mice via release of TSG6 and suppression of STAT3 activation. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wan, Y.M.; Wu, H.M.; Li, Y.H.; Xu, Z.Y.; Yang, J.H.; Liu, C.; He, Y.F.; Wang, M.J.; Wu, X.N.; Zhang, Y. TSG-6 Inhibits Oxidative Stress and Induces M2 Polarization of Hepatic Macrophages in Mice with Alcoholic Hepatitis via Suppression of STAT3 Activation. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chung, J.S.; Hwang, S.; Hong, J.E.; Jo, M.; Rhee, K.J.; Kim, S.; Jung, P.Y.; Yoon, Y.; Kang, S.H.; Ryu, H.; et al. Skeletal muscle satellite cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate acute alcohol-induced liver injury. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 19, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamas-Paz, A.; Hao, F.; Nelson, L.J.; Vázquez, M.T.; Canals, S.; Gómez Del Moral, M.; Martínez-Naves, E.; Nevzorova, Y.A.; Cubero, F.J. Alcoholic liver disease: Utility of animal models. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 5063–5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon-Warner, E.; Schrum, L.W.; Schmidt, C.M.; McKillop, I.H. Rodent models of alcoholic liver disease: Of mice and men. Alcohol 2012, 46, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, B.; Xu, M.J.; Bertola, A.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Liangpunsakul, S. Animal Models of Alcoholic Liver Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Relevance. Gene Expr. 2017, 17, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Fan, X.; Wang, Y.; Shen, M.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, S.; Yang, L. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Liver Immunity and Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 833878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Tan, Y.; Cai, M.; Zhao, T.; Mao, F.; Zhang, X.; Xu, W.; Yan, Z.; Qian, H.; Yan, Y. Human Umbilical Cord MSC-Derived Exosomes Suppress the Development of CCl4-Induced Liver Injury through Antioxidant Effect. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 6079642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yan, Y.; Jiang, W.; Tan, Y.; Zou, S.; Zhang, H.; Mao, F.; Gong, A.; Qian, H.; Xu, W. hucMSC Exosome-Derived GPX1 Is Required for the Recovery of Hepatic Oxidant Injury. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lou, G.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Y. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes as a new therapeutic strategy for liver diseases. Exp. Mol. Med. 2017, 49, e346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.Y.; Lai, R.C.; Wong, W.; Dan, Y.Y.; Lim, S.K.; Ho, H.K. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote hepatic regeneration in drug-induced liver injury models. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2014, 5, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jun, J.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, J.H.; Lim, J.Y.; Kim, K.; Kim, G.J. Exosomes from Placenta-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Are Involved in Liver Regeneration in Hepatic Failure Induced by Bile Duct Ligation. Stem Cells Int. 2020, 2020, 5485738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Xu, R.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, L.; Shi, M.; Wang, F.S. Implications of the immunoregulatory functions of mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of human liver diseases. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2011, 8, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arabpour, M.; Saghazadeh, A.; Rezaei, N. Anti-inflammatory and M2 macrophage polarization-promoting effect of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 97, 107823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xia, J.; Huang, R.; Hu, Y.; Fan, J.; Shu, Q.; Xu, J. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles alter disease outcomes via endorsement of macrophage polarization. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, J.; Patel, T. The mesenchymal stem cell secretome as an acellular regenerative therapy for liver disease. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 54, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, H.Y.; Zhang, X.C.; Jia, B.B.; Cao, Y.; Yan, K.; Li, J.Y.; Tao, L.; Jie, Z.G.; Liu, Q.W. Exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells alleviate acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure through activating ERK and IGF-1R/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 147, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Song, P.; Pan, W.; Xu, P.; Wang, G.; Hu, P.; Wang, Z.; Huang, K.; et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived Extracellular Vesicles Alleviate Traumatic Hemorrhagic Shock Induced Hepatic Injury via IL-10/PTPN22-Mediated M2 Kupffer Cell Polarization. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 811164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.Y.; Jang, Y.J.; Lim, H.J.; Han, J.; Lee, J.; Lee, G.; Park, J.Y.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Do, B.R.; et al. Milk Fat Globule-EGF Factor 8, Secreted by Mesenchymal Stem Cells, Protects Against Liver Fibrosis in Mice. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 1174–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, S.; Bi, Y.; Duan, Z.; Chang, Y.; Hong, F.; Chen, Y. Stem cell transplantation for treating liver diseases: Progress and remaining challenges. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 3954–3966. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Foo, J.B.; Looi, Q.H.; Chong, P.P.; Hassan, N.H.; Yeo, G.E.C.; Ng, C.Y.; Koh, B.; How, C.W.; Lee, S.H.; Law, J.X. Comparing the Therapeutic Potential of Stem Cells and their Secretory Products in Regenerative Medicine. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 2616807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veerman, R.E.; Teeuwen, L.; Czarnewski, P.; Güclüler Akpinar, G.; Sandberg, A.; Cao, X.; Pernemalm, M.; Orre, L.M.; Gabrielsson, S.; Eldh, M. Molecular evaluation of five different isolation methods for extracellular vesicles reveals different clinical applicability and subcellular origin. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.M.; Wang, M.Z. Overview of Extracellular Vesicles, Their Origin, Composition, Purpose, and Methods for Exosome Isolation and Analysis. Cells 2019, 8, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kou, M.; Huang, L.; Yang, J.; Chiang, Z.; Chen, S.; Liu, J.; Guo, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Xu, X.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles for immunomodulation and regeneration: A next generation therapeutic tool? Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhinaraset, M.; Wigglesworth, C.; Takeuchi, D.T. Social and Cultural Contexts of Alcohol Use: Influences in a Social-Ecological Framework. Alcohol Res. 2016, 38, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

| Strategy for Treatment | Therapeutic Agent | Mechanism | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blocking alcohol binge | Naltrexone | Blocking opioid receptor to reduce craving for alcohol | Increasing risk of drug-related hepatoxicity Persistent progression of ALD despite of abstinence from alcohol |

| Baclofen | Interfering GABA to reduce craving for alcohol | ||

| Acamprosate | Interfering GABA to reduce craving for alcohol | ||

| Disulfiram | Inhibiting ADH to cause great hangover after drink | ||

| Lowering oxidative stress | Vitamin E | Neutralizing free radicals, Preventing lipid peroxidation, Inhibiting activation of NF-κB | Insignificant therapeutic effect |

| NAC | Increasing glutathione level, Stabilizing glutamate system | Insignificant therapeutic effect in long term study | |

| SAMe | Regulating glutathione synthesis, Improving mitochondria dysfunction | Insignificant therapeutic effect, Insufficient clinical trials | |

| Promoting liver regeneration | G-CSF | Increasing CD34+ cells, hepatic progenitor cells and HGF level | Unveiled therapeutic mechanism |

| IL-22 | Promoting cell proliferation | Risk of liver cancer | |

| Alleviating Inflammation | Corticosteroid | Reducing inflammatory cytokine | Insignificant effects to corticosteroid non-responding patients |

| Pentoxifylline | Suppressing TNF-α synthesis | Insignificant therapeutic effect | |

| Infliximab | Binding with TNF-α to block its action Ameliorating leukocyte infiltration | Risk of infection | |

| IL-1β antagonist (anakinra) | Inhibiting IL-1β by binding with IL-1R1 | Insufficient study in ALD | |

| Canakinumab | Binding with IL-1β to block its action | Insufficient study in ALD | |

| IL-22, F-652 | Activating STAT3 | Insufficient clinical trials |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, J.; Lee, C.; Hur, J.; Jung, Y. Current Therapeutic Options and Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Alcoholic Liver Disease. Cells 2023, 12, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12010022

Han J, Lee C, Hur J, Jung Y. Current Therapeutic Options and Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Alcoholic Liver Disease. Cells. 2023; 12(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Jinsol, Chanbin Lee, Jin Hur, and Youngmi Jung. 2023. "Current Therapeutic Options and Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Alcoholic Liver Disease" Cells 12, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12010022