Cardiovascular and Metabolic Benefits of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Phenolic Compounds: Mechanistic Insights from In Vivo Studies

Abstract

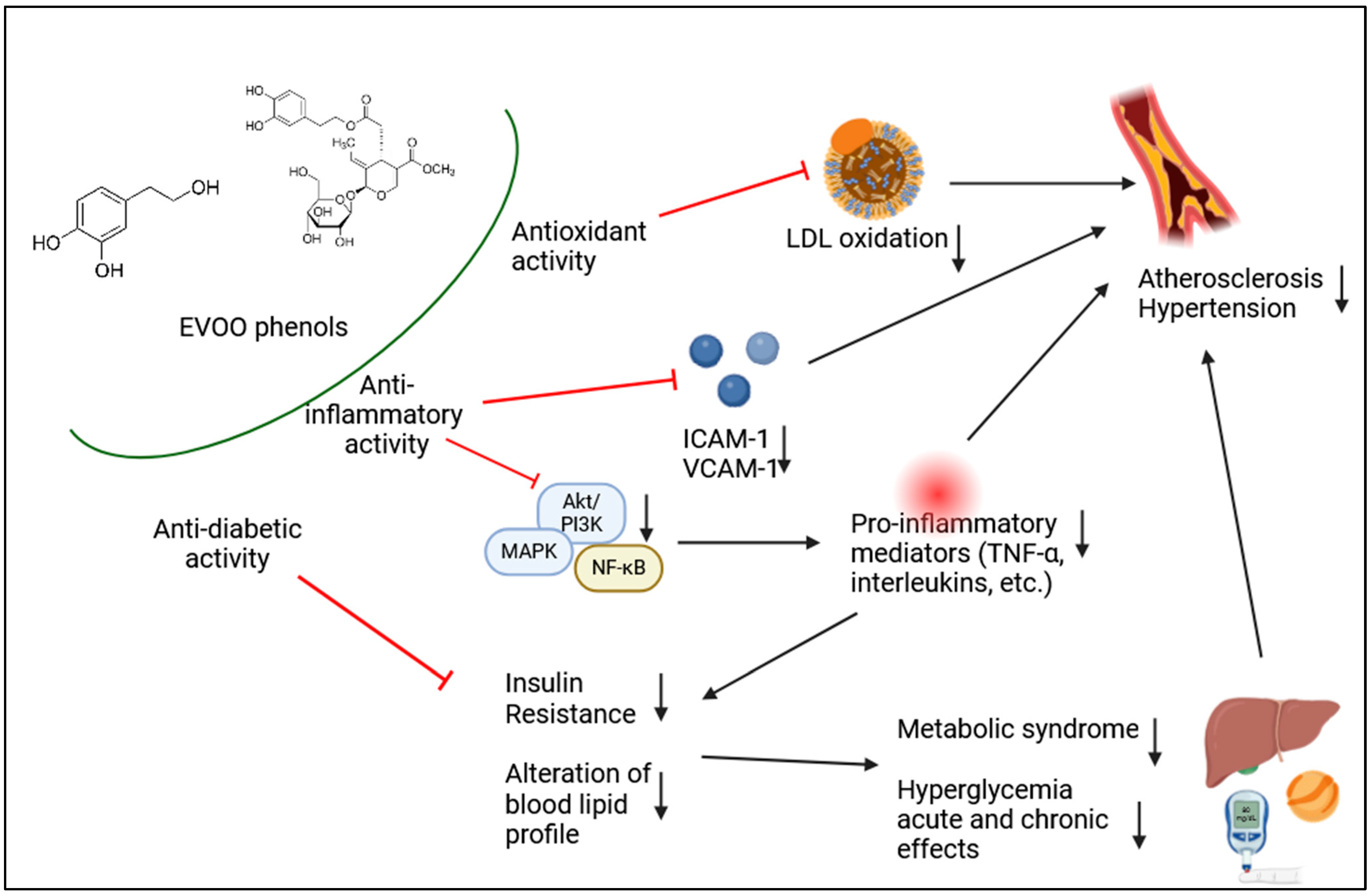

:1. Introduction

2. Clinical and Animal Studies

2.1. Nutraceuticals Formulations Containing HT

2.1.1. Safety of HT Used as Novel Food

2.1.2. Animal Studies

2.1.3. Human Clinical Trials

2.2. Nutraceuticals Formulations Containing Other EVOO Polyphenols

2.2.1. Animal Studies

2.2.2. Human Clinical Trials

2.3. Studies Using Functional Oils Enriched with EVOO Phenolic Fraction

Clinical Studies

3. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Carpena, M.; Lourenco-Lopes, C.; Gallardo-Gomez, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Bioactive Compounds and Quality of Extra Virgin Olive Oil. Foods 2020, 9, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicerale, S.; Conlan, X.A.; Sinclair, A.J.; Keast, R.S. Chemistry and health of olive oil phenolics. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 49, 218–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicerale, S.; Lucas, L.; Keast, R. Biological activities of phenolic compounds present in virgin olive oil. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 458–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Lopez, P.; Lozano-Sanchez, J.; Borras-Linares, I.; Emanuelli, T.; Menendez, J.A.; Segura-Carretero, A. Structure-Biological Activity Relationships of Extra-Virgin Olive Oil Phenolic Compounds: Health Properties and Bioavailability. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucciantini, M.; Leri, M.; Nardiello, P.; Casamenti, F.; Stefani, M. Olive Polyphenols: Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leri, M.; Scuto, M.; Ontario, M.L.; Calabrese, V.; Calabrese, E.J.; Bucciantini, M.; Stefani, M. Healthy Effects of Plant Polyphenols: Molecular Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finicelli, M.; Squillaro, T.; Galderisi, U.; Peluso, G. Polyphenols, the Healthy Brand of Olive Oil: Insights and Perspectives. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendini, A.; Cerretani, L.; Carrasco-Pancorbo, A.; Gomez-Caravaca, A.M.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernandez-Gutierrez, A.; Lercker, G. Phenolic molecules in virgin olive oils: A survey of their sensory properties, health effects, antioxidant activity and analytical methods. An overview of the last decade. Molecules 2007, 12, 1679–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanali, C.; Della Posta, S.; Vilmercati, A.; Dugo, L.; Russo, M.; Petitti, T.; Mondello, L.; de Gara, L. Extraction, Analysis, and Antioxidant Activity Evaluation of Phenolic Compounds in Different Italian Extra-Virgin Olive Oils. Molecules 2018, 23, 3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkoula, E.; Skantzari, A.; Melliou, E.; Magiatis, P. Direct measurement of oleocanthal and oleacein levels in olive oil by quantitative (1)H NMR. Establishment of a new index for the characterization of extra virgin olive oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 11696–11703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, A.; Rodriguez-Morato, J.; Olesti, E.; Pujadas, M.; Perez-Mana, C.; Khymenets, O.; Fito, M.; Covas, M.I.; Sola, R.; Motilva, M.J.; et al. Analysis of free hydroxytyrosol in human plasma following the administration of olive oil. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1437, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boronat, A.; Rodriguez-Morato, J.; Serreli, G.; Fito, M.; Tyndale, R.F.; Deiana, M.; de la Torre, R. Contribution of Biotransformations Carried Out by the Microbiota, Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes, and Transport Proteins to the Biological Activities of Phytochemicals Found in the Diet. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 2172–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serreli, G.; Le Sayec, M.; Diotallevi, C.; Teissier, A.; Deiana, M.; Corona, G. Conjugated Metabolites of Hydroxytyrosol and Tyrosol Contribute to the Maintenance of Nitric Oxide Balance in Human Aortic Endothelial Cells at Physiologically Relevant Concentrations. Molecules 2021, 26, 7480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serreli, G.; Melis, M.P.; Corona, G.; Deiana, M. Modulation of LPS-induced nitric oxide production in intestinal cells by hydroxytyrosol and tyrosol metabolites: Insight into the mechanism of action. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2019, 125, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Exposito, M.J.; Carrera-Gonzalez, M.P.; Mayas, M.D.; Martinez-Martos, J.M. Gender differences in the antioxidant response of oral administration of hydroxytyrosol and oleuropein against N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-induced glioma. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 110023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaduganathan, M.; Mensah, G.A.; Turco, J.V.; Fuster, V.; Roth, G.A. The Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk: A Compass for Future Health. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 2361–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cesare, M.; Perel, P.; Taylor, S.; Kabudula, C.; Bixby, H.; Gaziano, T.A.; McGhie, D.V.; Mwangi, J.; Pervan, B.; Narula, J.; et al. The Heart of the World. Glob. Heart 2024, 19, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aunon-Calles, D.; Canut, L.; Visioli, F. Toxicological evaluation of pure hydroxytyrosol. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2013, 55, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aunon-Calles, D.; Giordano, E.; Bohnenberger, S.; Visioli, F. Hydroxytyrosol is not genotoxic in vitro. Pharmacol. Res. 2013, 74, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efsa Panel on Dietetic Products, N.; Allergies; Turck, D.; Bresson, J.L.; Burlingame, B.; Dean, T.; Fairweather-Tait, S.; Heinonen, M.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Mangelsdorf, I.; et al. Safety of hydroxytyrosol as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EC) No 258/97. EFSA J.. Eur. Food Saf. Auth. 2017, 15, e04728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Almazan, M.; Pulido-Moran, M.; Moreno-Fernandez, J.; Ramirez-Tortosa, C.; Rodriguez-Garcia, C.; Quiles, J.L.; Ramirez-Tortosa, M. Hydroxytyrosol: Bioavailability, toxicity, and clinical applications. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acin, S.; Navarro, M.A.; Arbones-Mainar, J.M.; Guillen, N.; Sarria, A.J.; Carnicer, R.; Surra, J.C.; Orman, I.; Segovia, J.C.; Torre Rde, L.; et al. Hydroxytyrosol administration enhances atherosclerotic lesion development in apo E deficient mice. J Biochem 2006, 140, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez de Las Hazas, M.C.; Del Saz-Lara, A.; Cedo, L.; Crespo, M.C.; Tome-Carneiro, J.; Chapado, L.A.; Macia, A.; Visioli, F.; Escola-Gil, J.C.; Davalos, A. Hydroxytyrosol Induces Dyslipidemia in an ApoB100 Humanized Mouse Model. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, e2300508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Correa, J.A.; Navas, M.D.; Munoz-Marin, J.; Trujillo, M.; Fernandez-Bolanos, J.; de la Cruz, J.P. Effects of hydroxytyrosol and hydroxytyrosol acetate administration to rats on platelet function compared to acetylsalicylic acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 7872–7876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Marin, J.; De la Cruz, J.P.; Reyes, J.J.; Lopez-Villodres, J.A.; Guerrero, A.; Lopez-Leiva, I.; Espartero, J.L.; Labajos, M.T.; Gonzalez-Correa, J.A. Hydroxytyrosyl alkyl ether derivatives inhibit platelet activation after oral administration to rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2013, 58, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirozzi, C.; Lama, A.; Simeoli, R.; Paciello, O.; Pagano, T.B.; Mollica, M.P.; Di Guida, F.; Russo, R.; Magliocca, S.; Canani, R.B.; et al. Hydroxytyrosol prevents metabolic impairment reducing hepatic inflammation and restoring duodenal integrity in a rat model of NAFLD. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 30, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Xu, J.; Zou, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, C.; Zheng, A.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Szeto, I.M.; Shi, Y.; et al. Hydroxytyrosol prevents diet-induced metabolic syndrome and attenuates mitochondrial abnormalities in obese mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 67, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Cruz Cortes, J.P.; Vallejo-Carmona, L.; Arrebola, M.M.; Martin-Aurioles, E.; Rodriguez-Perez, M.D.; Ortega-Hombrados, L.; Verdugo, C.; Fernandez-Prior, M.A.; Bermudez-Oria, A.; Gonzalez-Correa, J.A. Synergistic Effect of 3‘,4’-Dihidroxifenilglicol and Hydroxytyrosol on Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress and Some Cardiovascular Biomarkers in an Experimental Model of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo, A.; Alvarez-Soria, M.J.; Aranda-Villalobos, P.; Martinez-Rodriguez, A.M.; Martinez-Lara, E.; Siles, E. Hydroxytyrosol, a Promising Supplement in the Management of Human Stroke: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Fogacci, F.; Di Micoli, A.; Veronesi, M.; Grandi, E.; Borghi, C. Hydroxytyrosol-Rich Olive Extract for Plasma Cholesterol Control. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D‘Addato, S.; Scandiani, L.; Mombelli, G.; Focanti, F.; Pelacchi, F.; Salvatori, E.; Di Loreto, G.; Comandini, A.; Maffioli, P.; Derosa, G. Effect of a food supplement containing berberine, monacolin K, hydroxytyrosol and coenzyme Q(10) on lipid levels: A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2017, 11, 1585–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiros-Fernandez, R.; Lopez-Plaza, B.; Bermejo, L.M.; Palma Milla, S.; Zangara, A.; Candela, C.G. Oral Supplement Containing Hydroxytyrosol and Punicalagin Improves Dyslipidemia in an Adult Population without Co-Adjuvant Treatment: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled and Crossover Trial. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiros-Fernandez, R.; Lopez-Plaza, B.; Bermejo, L.M.; Palma-Milla, S.; Gomez-Candela, C. Supplementation with Hydroxytyrosol and Punicalagin Improves Early Atherosclerosis Markers Involved in the Asymptomatic Phase of Atherosclerosis in the Adult Population: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colica, C.; Di Renzo, L.; Trombetta, D.; Smeriglio, A.; Bernardini, S.; Cioccoloni, G.; Costa de Miranda, R.; Gualtieri, P.; Sinibaldi Salimei, P.; De Lorenzo, A. Antioxidant Effects of a Hydroxytyrosol-Based Pharmaceutical Formulation on Body Composition, Metabolic State, and Gene Expression: A Randomized Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 2473495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Huertas, E.; Fonolla, J. Hydroxytyrosol supplementation increases vitamin C levels in vivo. A human volunteer trial. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leger, C.L.; Carbonneau, M.A.; Michel, F.; Mas, E.; Monnier, L.; Cristol, J.P.; Descomps, B. A thromboxane effect of a hydroxytyrosol-rich olive oil wastewater extract in patients with uncomplicated type I diabetes. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 727–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobili, V.; Alisi, A.; Mosca, A.; Crudele, A.; Zaffina, S.; Denaro, M.; Smeriglio, A.; Trombetta, D. The Antioxidant Effects of Hydroxytyrosol and Vitamin E on Pediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, in a Clinical Trial: A New Treatment? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2019, 31, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fytili, C.; Nikou, T.; Tentolouris, N.; Tseti, I.K.; Dimosthenopoulos, C.; Sfikakis, P.P.; Simos, D.; Kokkinos, A.; Skaltsounis, A.L.; Katsilambros, N.; et al. Effect of Long-Term Hydroxytyrosol Administration on Body Weight, Fat Mass and Urine Metabolomics: A Randomized Double-Blind Prospective Human Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binou, P.; Stergiou, A.; Kosta, O.; Tentolouris, N.; Karathanos, V.T. Positive contribution of hydroxytyrosol-enriched wheat bread to HbA(1)c levels, lipid profile, markers of inflammation and body weight in subjects with overweight/obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023, 62, 2165–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coni, E.; Di Benedetto, R.; Di Pasquale, M.; Masella, R.; Modesti, D.; Mattei, R.; Carlini, E.A. Protective effect of oleuropein, an olive oil biophenol, on low density lipoprotein oxidizability in rabbits. Lipids 2000, 35, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreadou, I.; Iliodromitis, E.K.; Mikros, E.; Constantinou, M.; Agalias, A.; Magiatis, P.; Skaltsounis, A.L.; Kamber, E.; Tsantili-Kakoulidou, A.; Kremastinos, D.T. The olive constituent oleuropein exhibits anti-ischemic, antioxidative, and hypolipidemic effects in anesthetized rabbits. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 2213–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreadou, I.; Benaki, D.; Efentakis, P.; Bibli, S.I.; Milioni, A.I.; Papachristodoulou, A.; Zoga, A.; Skaltsounis, A.L.; Mikros, E.; Iliodromitis, E.K. The natural olive constituent oleuropein induces nutritional cardioprotection in normal and cholesterol-fed rabbits: Comparison with preconditioning. Planta Med. 2015, 81, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Yang, Z.; Fang, K.; Shi, Z.L.; Ren, D.H.; Sun, J. Oleuropein prevents the development of experimental autoimmune myocarditis in rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 48, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.X.; Zhang, Y.H.; Guo, R.N.; Zhao, S.N. Inhibition of MEK/ERK/STAT3 signaling in oleuropein treatment inhibits myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Azzawie, H.F.; Alhamdani, M.S. Hypoglycemic and antioxidant effect of oleuropein in alloxan-diabetic rabbits. Life Sci. 2006, 78, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murotomi, K.; Umeno, A.; Yasunaga, M.; Shichiri, M.; Ishida, N.; Koike, T.; Matsuo, T.; Abe, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Nakajima, Y. Oleuropein-Rich Diet Attenuates Hyperglycemia and Impaired Glucose Tolerance in Type 2 Diabetes Model Mouse. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 6715–6722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuem, N.; Song, S.J.; Yu, R.; Yun, J.W.; Park, T. Oleuropein attenuates visceral adiposity in high-fat diet-induced obese mice through the modulation of WNT10b- and galanin-mediated signalings. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 2166–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepore, S.M.; Maggisano, V.; Bulotta, S.; Mignogna, C.; Arcidiacono, B.; Procopio, A.; Brunetti, A.; Russo, D.; Celano, M. Oleacein Prevents High Fat Diet-Induced Adiposity and Ameliorates Some Biochemical Parameters of Insulin Sensitivity in Mice. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, G.E.; Lepore, S.M.; Morittu, V.M.; Arcidiacono, B.; Colica, C.; Procopio, A.; Maggisano, V.; Bulotta, S.; Costa, N.; Mignogna, C.; et al. Effects of Oleacein on High-Fat Diet-Dependent Steatosis, Weight Gain, and Insulin Resistance in Mice. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Garcia, R.; Sanchez-Hidalgo, M.; Alcarranza, M.; Vazquez-Roman, M.V.; de Sotomayor, M.A.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, M.L.; de Andres, M.C.; Alarcon-de-la-Lastra, C. Effects of Dietary Oleacein Treatment on Endothelial Dysfunction and Lupus Nephritis in Balb/C Pristane-Induced Mice. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hou, J.; Li, X.; Chen, P.; Chen, F.; Pan, Y.; Deng, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, R.; Luo, T. Tyrosol regulates hepatic lipid metabolism in high-fat diet-induced NAFLD mice. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 3752–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Wang, X.; Hou, C.; Yang, L.; Li, H.; Guo, J.; Huo, C.; Wang, M.; Miao, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Oleuropein improves mitochondrial function to attenuate oxidative stress by activating the Nrf2 pathway in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Neuropharmacology 2017, 113, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Frost, B.; Liu, J. Oleuropein, unexpected benefits! Oncotarget 2017, 8, 17409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visioli, F.; Caruso, D.; Galli, C.; Viappiani, S.; Galli, G.; Sala, A. Olive oils rich in natural catecholic phenols decrease isoprostane excretion in humans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 278, 797–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Morato, J.; Boronat, A.; Serreli, G.; Enriquez, L.; Gomez-Gomez, A.; Pozo, O.J.; Fito, M.; de la Torre, R. Effects of Wine and Tyrosol on the Lipid Metabolic Profile of Subjects at Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: Potential Cardioprotective Role of Ceramides. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boronat, A.; Mateus, J.; Soldevila-Domenech, N.; Guerra, M.; Rodriguez-Morato, J.; Varon, C.; Munoz, D.; Barbosa, F.; Morales, J.C.; Gaedigk, A.; et al. Cardiovascular benefits of tyrosol and its endogenous conversion into hydroxytyrosol in humans. A randomized, controlled trial. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 143, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Morato, J.; Robledo, P.; Tanner, J.A.; Boronat, A.; Perez-Mana, C.; Oliver Chen, C.Y.; Tyndale, R.F.; de la Torre, R. CYP2D6 and CYP2A6 biotransform dietary tyrosol into hydroxytyrosol. Food Chem. 2017, 217, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bock, M.; Derraik, J.G.; Brennan, C.M.; Biggs, J.B.; Morgan, P.E.; Hodgkinson, S.C.; Hofman, P.L.; Cutfield, W.S. Olive (Olea europaea L.) leaf polyphenols improve insulin sensitivity in middle-aged overweight men: A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patti, A.M.; Carruba, G.; Cicero, A.F.G.; Banach, M.; Nikolic, D.; Giglio, R.V.; Terranova, A.; Soresi, M.; Giannitrapani, L.; Montalto, G.; et al. Daily Use of Extra Virgin Olive Oil with High Oleocanthal Concentration Reduced Body Weight, Waist Circumference, Alanine Transaminase, Inflammatory Cytokines and Hepatic Steatosis in Subjects with the Metabolic Syndrome: A 2-Month Intervention Study. Metabolites 2020, 10, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsa, M.E.; Ketselidi, K.; Kalliostra, M.; Ioannidis, A.; Rojas Gil, A.P.; Diamantakos, P.; Melliou, E.; Magiatis, P.; Nomikos, T. Acute Antiplatelet Effects of an Oleocanthal-Rich Olive Oil in Type II Diabetic Patients: A Postprandial Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, K.; Melliou, E.; Li, X.; Pedersen, T.L.; Wang, S.C.; Magiatis, P.; Newman, J.W.; Holt, R.R. Oleocanthal-rich extra virgin olive oil demonstrates acute anti-platelet effects in healthy men in a randomized trial. J. Funct Foods 2017, 36, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Garcia, I.; Ortiz-Flores, R.; Badia, R.; Garcia-Borrego, A.; Garcia-Fernandez, M.; Lara, E.; Martin-Montanez, E.; Garcia-Serrano, S.; Valdes, S.; Gonzalo, M.; et al. Rich oleocanthal and oleacein extra virgin olive oil and inflammatory and antioxidant status in people with obesity and prediabetes. The APRIL study: A randomised, controlled crossover study. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Aros, F.; Gomez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutierrez, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. New Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billingsley, H.E.; Carbone, S. The antioxidant potential of the Mediterranean diet in patients at high cardiovascular risk: An in-depth review of the PREDIMED. Nutr. Diabetes 2018, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaner, O.; Covas, M.I.; Khymenets, O.; Nyyssonen, K.; Konstantinidou, V.; Zunft, H.F.; de la Torre, R.; Munoz-Aguayo, D.; Vila, J.; Fito, M. Protection of LDL from oxidation by olive oil polyphenols is associated with a downregulation of CD40-ligand expression and its downstream products in vivo in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1238–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaner, O.; Fito, M.; Lopez-Sabater, M.C.; Poulsen, H.E.; Nyyssonen, K.; Schroder, H.; Salonen, J.T.; De la Torre-Carbot, K.; Zunft, H.F.; De la Torre, R.; et al. The effect of olive oil polyphenols on antibodies against oxidized LDL. A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 30, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covas, M.I.; Nyyssonen, K.; Poulsen, H.E.; Kaikkonen, J.; Zunft, H.J.; Kiesewetter, H.; Gaddi, A.; de la Torre, R.; Mursu, J.; Baumler, H.; et al. The effect of polyphenols in olive oil on heart disease risk factors: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 145, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernaez, A.; Remaley, A.T.; Farras, M.; Fernandez-Castillejo, S.; Subirana, I.; Schroder, H.; Fernandez-Mampel, M.; Munoz-Aguayo, D.; Sampson, M.; Sola, R.; et al. Olive Oil Polyphenols Decrease LDL Concentrations and LDL Atherogenicity in Men in a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1692–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covas, M.I.; de la Torre, K.; Farre-Albaladejo, M.; Kaikkonen, J.; Fito, M.; Lopez-Sabater, C.; Pujadas-Bastardes, M.A.; Joglar, J.; Weinbrenner, T.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M.; et al. Postprandial LDL phenolic content and LDL oxidation are modulated by olive oil phenolic compounds in humans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 40, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, W.; George, E.S.; Mayr, H.L.; Thomas, C.J.; Sarapis, K.; Moschonis, G.; Kennedy, G.; Pipingas, A.; Willcox, J.C.; Prendergast, L.A.; et al. Effect of high polyphenol extra virgin olive oil on markers of cardiovascular disease risk in healthy Australian adults (OLIVAUS): A protocol for a double-blind randomised, controlled, cross-over study. Nutr. Diet. J. Dietit. Assoc. Aust. 2020, 77, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarapis, K.; George, E.S.; Marx, W.; Mayr, H.L.; Willcox, J.; Esmaili, T.; Powell, K.L.; Folasire, O.S.; Lohning, A.E.; Garg, M.; et al. Extra virgin olive oil high in polyphenols improves antioxidant status in adults: A double-blind, randomized, controlled, cross-over study (OLIVAUS). Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 1073–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarapis, K.; George, E.S.; Marx, W.; Mayr, H.L.; Willcox, J.; Powell, K.L.; Folasire, O.S.; Lohning, A.E.; Prendergast, L.A.; Itsiopoulos, C.; et al. Extra-virgin olive oil improves HDL lipid fraction but not HDL-mediated cholesterol efflux capacity: A double-blind, randomized, controlled, cross-over study (OLIVAUS). Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 130, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarapis, K.; Thomas, C.J.; Hoskin, J.; George, E.S.; Marx, W.; Mayr, H.L.; Kennedy, G.; Pipingas, A.; Willcox, J.C.; Prendergast, L.A.; et al. The Effect of High Polyphenol Extra Virgin Olive Oil on Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffness in Healthy Australian Adults: A Randomized, Controlled, Cross-Over Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandouzi, N.; Zahedmehr, A.; Nasrollahzadeh, J. Effect of polyphenol-rich extra-virgin olive oil on lipid profile and inflammatory biomarkers in patients undergoing coronary angiography: A randomised, controlled, clinical trial. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 72, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farras, M.; Valls, R.M.; Fernandez-Castillejo, S.; Giralt, M.; Sola, R.; Subirana, I.; Motilva, M.J.; Konstantinidou, V.; Covas, M.I.; Fito, M. Olive oil polyphenols enhance the expression of cholesterol efflux related genes in vivo in humans. A randomized controlled trial. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 1334–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Luna, R.; Munoz-Hernandez, R.; Miranda, M.L.; Costa, A.F.; Jimenez-Jimenez, L.; Vallejo-Vaz, A.J.; Muriana, F.J.; Villar, J.; Stiefel, P. Olive oil polyphenols decrease blood pressure and improve endothelial function in young women with mild hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2012, 25, 1299–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls, R.M.; Farras, M.; Suarez, M.; Fernandez-Castillejo, S.; Fito, M.; Konstantinidou, V.; Fuentes, F.; Lopez-Miranda, J.; Giralt, M.; Covas, M.I.; et al. Effects of functional olive oil enriched with its own phenolic compounds on endothelial function in hypertensive patients. A randomised controlled trial. Food Chem. 2015, 167, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, H.M.; de Deus Mendonca, R.; Laclaustra, M.; Moreno-Franco, B.; Akesson, A.; Guallar-Castillon, P.; Donat-Vargas, C. The intake of flavonoids, stilbenes, and tyrosols, mainly consumed through red wine and virgin olive oil, is associated with lower carotid and femoral subclinical atherosclerosis and coronary calcium. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 2697–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, Y.M.; Bemudez, B.; Lopez, S.; Abia, R.; Villar, J.; Muriana, F.J. Minor compounds of olive oil have postprandial anti-inflammatory effects. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 98, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruano, J.; Lopez-Miranda, J.; de la Torre, R.; Delgado-Lista, J.; Fernandez, J.; Caballero, J.; Covas, M.I.; Jimenez, Y.; Perez-Martinez, P.; Marin, C.; et al. Intake of phenol-rich virgin olive oil improves the postprandial prothrombotic profile in hypercholesterolemic patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 86, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidou, V.; Covas, M.I.; Munoz-Aguayo, D.; Khymenets, O.; de la Torre, R.; Saez, G.; Tormos Mdel, C.; Toledo, E.; Marti, A.; Ruiz-Gutierrez, V.; et al. In vivo nutrigenomic effects of virgin olive oil polyphenols within the frame of the Mediterranean diet: A randomized controlled trial. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2010, 24, 2546–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.S.; Marshall, S.; Mayr, H.L.; Trakman, G.L.; Tatucu-Babet, O.A.; Lassemillante, A.M.; Bramley, A.; Reddy, A.J.; Forsyth, A.; Tierney, A.C.; et al. The effect of high-polyphenol extra virgin olive oil on cardiovascular risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2772–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel, S.; Mesa, M.D.; de la Torre, R.; Espejo, J.A.; Fernandez-Navarro, J.R.; Fito, M.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, E.; Rosa, C.; Marchal, R.; Alche, J.D.; et al. The NUTRAOLEOUM Study, a randomized controlled trial, for achieving nutritional added value for olive oils. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Rodriguez, E.; Biel-Glesson, S.; Fernandez-Navarro, J.R.; Calleja, M.A.; Espejo-Calvo, J.A.; Gil-Extremera, B.; de la Torre, R.; Fito, M.; Covas, M.I.; Vilchez, P.; et al. Effects of Virgin Olive Oils Differing in Their Bioactive Compound Contents on Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Healthy Adults: A Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njike, V.Y.; Ayettey, R.; Treu, J.A.; Doughty, K.N.; Katz, D.L. Post-prandial effects of high-polyphenolic extra virgin olive oil on endothelial function in adults at risk for type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled crossover trial. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021, 330, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, C.; Filesi, C.; Vari, R.; Scazzocchio, B.; Filardi, T.; Fogliano, V.; D‘Archivio, M.; Giovannini, C.; Lenzi, A.; Morano, S.; et al. Consumption of extra-virgin olive oil rich in phenolic compounds improves metabolic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A possible involvement of reduced levels of circulating visfatin. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2016, 39, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, S.; Cariello, M.; Piccinin, E.; Sabba, C.; Moschetta, A. Extra Virgin Olive Oil: Lesson from Nutrigenomics. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Intervention | Concentration Tested | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal models | |||

| Homozygous apoE KO mice | 10 mg/kg/day for ten weeks | Harmful effects by decreasing apolipoprotein A-I and increasing atherosclerotic lesion areas circulating monocytes expressing Mac-1 and total cholesterol | [22] |

| Human APOB100 transgenic (HAPOB100Tg) male mice on the C57BL/6 background | Purified control diet (n = 8) without or with HT (0.03%) for 8 weeks | Induced systemic dyslipidemia and impaired glucose metabolism. Accumulation of triacylglycerols in mesenteric and epididymal white adipose tissues | [23] |

| Healthy male Wistar rats | 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 mg/kg/day for seven days. | No toxicity observed and inhibition of platelet aggregation (ID50 48.25 mg/kg) and of platelet synthesis of TxB2. Increase in NO release | [24] |

| Healthy male Wistar rats | HT esterified derivatives, 20 mg/kg/day for seven days | Inhibition of platelet aggregation, TxB2, and plasma concentration of lipid peroxides. Increase in nitrites and GSH in red blood cells | [25] |

| Nutritional rat model of insulin resistance (IR) and NAFLD by HFD | 10 mg/kg/day for five weeks | Reduction in serum cholesterol, AST, and ALT. Improvement of insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance. Increase in hepatic PPAR-α. Reduction in liver inflammation and the nitrosylation of proteins, ROS release, and lipid peroxidation | [26] |

| HFD in C57BL/6J mice | 10 mg/kg/day for seventeen weeks | Counteraction of oxidative stress by inducing antioxidant enzyme activities, and modulation of the expression of mitochondrial fission marker Drp1 and mitochondrial complex subunits | [27] |

| C57BL/6J mice db/db diabetic model | 10 mg/kg/day for seventeen weeks | Decrease in fasting glucose, serum lipids, and the oxidation levels of proteins and lipids | [27] |

| Experimental adult male Wistar rats model of T1D | HT 0.5 mg/kg/day for two months | Reduction in platelet aggregation, myeloperoxidase, oxidative and nitrosative stress, production of prostacyclin, and VCAM-1 | [28] |

| Clinical studies | |||

| Randomized, controlled, double-blind pilot study involving eight individuals with minor or moderately severe acute ischemic stroke | Treatment with a daily nutritional supplement containing 15 mg of HT (or placebo for 45 days) | Decrease in the percentage of diastolic blood pressure and glycated hemoglobin. Modulation of NO production and the expression of apolipoproteins | [29] |

| Single-arm, non-controlled, non-randomized, prospective pilot clinical trial with thirty hypercholesterolemic volunteers | Dietary supplementation with highly standardized phenols (100 mg olive extract, 4–9% HT/day for four weeks) | Modulation of total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, systolic blood pressure, pulse pressure, uric acid, and fasting plasma glucose | [30] |

| Multicenter, randomized, double-blind controlled study involving 158 patients with mild or moderate hypercholesterolemia | Treatment with food supplement “Body Lipid” preparation (5 mg HT/day for four weeks) | Lowering of LDL levels with a reduction of −26.3% | [31] |

| Randomized, double-blind, controlled, crossover trial involving eighty-four subjects with hypertriglyceridemia, men and women, aged 45–65 years | Treatment with supplement containing 3.3 mg of HT from an olive fruit extract (three capsules/day for twenty weeks) | Decrease in LDL and triglycerides in plasma | [32] |

| Randomized, double-blind, controlled, crossover trial involving eighty-four subjects with hypertriglyceridemia, men and women, aged 45–65 years | Treatment with supplement containing 9.9 mg of HT (three capsules/day for twenty weeks) | Increase in endothelial function and reduced ox-LDL. Decreased systolic and diastolic blood pressure | [33] |

| Randomized double-blinded, placebo-controlled crossover trial involving twenty-eight patients, aged 18–65 years | Capsules incorporating 15 mg HT/day for three weeks | Increase in oxidation biomarkers, total antioxidant status, and SOD1. Decrease in NO metabolites and MDA | [34] |

| Intervention in fourteen volunteers with mild hyperlipidemia | 45 mg/day for eight weeks | No influence on biomarkers of CVD and inflammation, electrolyte balance, blood lipids, and liver or kidney functions. Increase in endogenous vitamin C concentration | [35] |

| Intervention in five 32–68 years old male patients | 25 mg of HT the first day and 12.5 mg/day the following three days | Decrease (46%) in serum TXB2 production. Enhancement of plasma antioxidant capacity. No effects on urinary 8-isoPGF2a and plasmatic albumin, bilirubin, uric acid, vitamin E, vitamin A, and β-carotene | [36] |

| Randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial involving eighty adolescent patients with biopsy-proven NAFLD | Pharmaceutical capsules containing 3.75 mg of HT, two capsules/day for four months | Decrease in triglyceride levels, oxidative stress parameters, insulin resistance, and steatosis | [37] |

| Randomized, double-blind prospective design including twenty-nine women with overweight/obesity | HT in two different doses (15 and 5 mg/day) for six months | Weight and visceral fat mass loss after four weeks | [38] |

| Sixty adults with overweight/obesity and T2D mellitus | 60 g of conventional whole wheat bread or whole wheat bread enriched with HT (54 mg/100 g) | HT-enriched bread group showed greater fat mass, glucose, blood lipid, insulin, TNF-α, adiponectin, and HbA1c decrease than whole wheat bread group | [39] |

| Compound Tested | Type of Intervention/Model | Concentration Tested | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal studies | ||||

| Oleuropein (Olp) | Female New Zealand white rabbits | 0.4 mg/kg b.w. daily for six weeks | Increase in the capacity of LDL to counteract oxidation and reduction in plasmatic levels of total, esterified, and free cholesterol | [40] |

| Male healthy or hypercholesterolemic New Zealand white rabbits | 10–20 mg/kg b.w. daily for six weeks | Reduction in infarct extent. Decrease in protein carbonyl and plasma lipid peroxidation product concentrations Reduction in total cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations in plasma | [41] | |

| Male New Zealand white rabbits preconditioned with ischemia/reperfusion | 20 mg/kg b.w. daily for six weeks | Increase in PI3K/Akt, eNOS, AMPK, and STAT 3 phosphorylation | [42] | |

| Adult male Lewis rats with experimental autoimmune myocarditis | 20 mg/kg b.w. daily for four weeks | Limitation of left ventricular end-systolic diameters, left ventricular end-diastolic diameters, left ventricular end-diastolic pressures, and improvement of ejection fractions. Inhibition of macrophage, CD4+, and CD8+ infiltration in myocardium. Decrease in serum IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6. Reduction in myocardial levels of p-IκBα, IKKα, and NF-κB p65 | [43] | |

| Experimental ischemia/reperfusion (myocardial I/R) in adult male Sprague-Dawley rats | 20 mg/kg b.w. daily for two days | Inhibition of myocardial infarction extent, LDH and CK MB serum levels, and attenuation of p53, ERK, caspase 3, MEK, and p-IκBα protein expression. Decrease in MDA, IL-1β, IL 6, and TNF-α; increase in GSH, SOD, and catalase levels | [44] | |

| Alloxan-induced diabetic male New Zealand rabbits | 20 mg/kg b.w. for sixteen weeks | Reduction in oxidative stress and hyperglycemia. Restoration of MDA levels, blood glucose, and most of the non-enzymatic and enzymatic antioxidant defenses | [45] | |

| Male TSOD mice | Olp-containing formulation “OPIACE”, Olp content exceeding 35% (w/w) for twenty-four weeks | Attenuation of impaired glucose tolerance and hyperglycemia from 10 to 24 weeks of age. No effects on obesity. Mild reduction in plasmatic oxidative stress by 26.2% | [46] | |

| HFD five-week-old male C57BL/6N mice | Olp-supplemented diet plus 0.03% (w/w) Olp | Reduction in body weight increment and visceral adiposity. Counteraction of elevations of adipogenic-related gene expression involved in WNT10b- and galanin-mediated signaling in adipose tissue | [47] | |

| Eight-week-old male normotensive Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats or spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) | 2 mL saline or oral gavage of Olp (60 mg/kg/day) | Significantly lowered blood pressure and modulation of Nrf-2 at hypothalamic level | [52] | |

| Oleacein (Ole) | HFD male C57BL/6JOlaHsd mice | 20 mg/kg b.w. daily for five weeks | Prevention of the enhancement of adipocyte size and reduction in the inflammatory infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages in adipose tissue. Restoration of the expression of PPARγ, FAS, adiponectin, SREBP-1, and Glut-4 | [48] |

| HFD male C57BL/6JolaHsd mice | 20 mg/kg b.w. daily for five weeks | Down-regulation of plasma glucose, cholesterol, and triglyceride serum levels in comparison with normocaloric diet-treated mice. Modulation of FAS and SREBP-1 | [49] | |

| 12-week-old female BALB/c pristane-treated mice | Ole-enriched diet (0.01% (w/w)) for 24 weeks | Normalization of eNOS synthase and NADPH oxidase-1 overexpression | [50] | |

| Tyrosol (Tyr) | LFD or HFD male C57BL/6J mice | LFD, HFD, or HFD supplemented with 0.025% (w/w) Tyr for 16 weeks | Binding with PPARα and activation of the transcription of downstream genes leading to lowered body weight and hepatic lipid accumulation | [51] |

| Human clinical studies | ||||

| Oleuropein (Olp) | Six healthy volunteers (males, non-smokers, aged 27–33) | 12.6, 23.7, 33.7, and 39.5 mg conveyed through olive oil, four times after one month of washout | Decrease in urinary excretion of 8-iso-PGF2a, | [54] |

| Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled crossover study involving forty-six middle-aged overweight men | Four capsules as a single dose (51.1 mg), daily for twelve weeks | 28% increase in pancreatic β-cell responsiveness and 15% increase in insulin sensitivity. Increase in IGFBP-1, IGFBP-2, and IL-6 concentrations. No effects on lipid profile, blood pressure, body composition, ultra-sensitive CRP, TNF-α, IL-8, carotid intima-media thickness, and liver function | [58] | |

| Tyrosol (Tyr) | Thirty-three volunteers (twelve women, twenty-one men) aged 50–80 with at least three major CVD risk factors | 1.4 + 25 mg Tyr + 0.2 HT (female volunteers) or 2.8 + 50 mg Tyr + 0.4 mg HT (male volunteers) conveyed through white wine, daily for four weeks | Lowering of three circulating ceramide (Cer) ratio levels and the alterations in plasma diacylglycerols concentrations | [55] |

| Oleocanthal (Olc) | Randomized, single-blinded crossover study, involving ten T2D patients | 120 g white bread combined with 39 g butter, 39 g butter, and 400 mg ibuprofen, 40 mL OO (phenolic content < 10 mg/Kg), 40 mL OO with 250 mg/Kg Olc or 40 mL OO with 500 mg/Kg Olc | Postprandial dose-dependent reduction in platelets’ sensitivity | [60] |

| Double-blind, randomized, controlled crossover study involving nine healthy men | 40 mL of EVOO matched for total phenolic content, either Tyr-poor with 1:2 Ole/Olc or 2:1 Ole/Olc, or predominantly Tyr | Inhibition of collagen-stimulated platelet aggregation consumption of EVOO rich in Olc. Enrichment with Ole and Tyr did not lead to significant changes | [61] | |

| Randomized, double-blind, crossover trial performed on people aged 40–65 years with obesity and prediabetes | EVOO rich in Ole and Olc or OO for 1 month | Decrease in weight, BMI, and blood glucose and increase in antioxidant defenses after treatment with EVOO in comparison with OO group | [62] |

| Type of Intervention | Concentration Tested | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical studies | |||

| EUROLIVE study: crossover, controlled trial involving 200 healthy male volunteers aged 20–60 | 3-week sequences of 25 mL/day of three OO with low (2.7 mg/kg), medium (164 mg/kg), and high (366 mg/kg) phenolic content | Counteraction of LDL oxidation with a significant decrease in IL8RA, ADRB2, OLR1, and CD40 gene expression and a decrease in LDL oxidation and intercellular adhesion molecule 1. Decrease in plasma apo B-100 concentrations and the number of small and total LDL particles | [65,66,67,68] |

| Crossover study design involving twelve male volunteers aged 20 to 22 | 40 mL of OO with low (2.7 mg/kg), moderate (164 mg/kg), and high (366 mg/kg) phenolic content (single administration) | Decrease in the degree of LDL oxidation proportionally to the phenolic content of OO | [69] |

| OLIVAUS study: double-blind, crossover, randomized, controlled trial involving fifty healthy volunteers (seventeen men, thirty-three women) aged 18–75 | 60 mL/day of either low-polyphenol EVOO (86 mg/kg) or high-polyphenol EVOO (360 mg/kg) for three weeks | Decrease in peripheral and central systolic blood pressure and plasma ox-LDL. Increase in TAC only in the high-polyphenol EVOO consumption. Decrease in hs-CRP levels only in the high-polyphenol EVOO-treated group | [70,71,72,73]. |

| Randomized, controlled, parallel-arm clinical trial involving forty men and post-menopausal women aged 20–75 with at least one classic CVD risk factor | Daily amount of 25 mL of ROO or EVOO with meals for 6 weeks | Reduction in plasma LDL-cholesterol and plasma CRP | [74] |

| Randomized, controlled, crossover trial involving thirteen pre-/hypertensive patients aged 20 to 75 (7 men and 6 women) | 30 mL of two similar OOs with moderate- (289 mg/kg) or high- (961 mg/kg) polyphenol content (single administration) | Postprandial enhancement of PPARα-, PPARγ-, PPARδ-, (PPAR)BP-, CD3-, 6ATP-binding cassette transporter-A1 and scavenger receptor class B type 1 gene expression in white blood cells | [75] |

| Double-blind, randomized, crossover dietary intervention study involving twenty-four young women with stage 1 essential hypertension or high-normal blood pressure | 30 mg/day of polyphenols from OO for four months | Decrease in diastolic and systolic blood pressure, associated with reduction in serum asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), plasma CRP, and ox-LDL only through the polyphenol-rich OO diet. Increase in plasma NO metabolites and hyperemic area after ischemia | [76] |

| Randomized, controlled, crossover study involving thirteen pre/hypertensive patients aged 20 to 75 (7 men and 6 women) | 30 mL of two similar OOs with moderate- (289 mg/kg) or high- (961 mg/kg) polyphenol content (single administration) | Improvement of endothelial function measured as ischemic reactive hyperemia, and decrease in ox-LDL in plasma after intake of EVOO with high-polyphenol content | [77] |

| Aragon Workers’ Health Study: prospective cohort study involving 2318 participants | Normal diet for four years | Lowering of the risk of CVD measured as presence of plaques in carotid and femoral arteries and coronary calcium associated with higher intake of polyphenols from EVOO | [78] |

| Randomized crossover and blind trial on fourteen healthy and fourteen male hypertriacylglycerolaemic subjects, aged 21–38 | Diet supplemented with ROO with no polyphenols or tocopherols or EVOO containing 1125 mg polyphenols/kg and 350 mg tocopherols/kg, for one week | Hypertriacylglycerolaemic and healthy volunteers showed lower incremental area under the curve for sVCAM-1 and sICAM-1 after the EVOO intervention | [79] |

| Randomized, sequential crossover study involving twenty-one hypercholesterolemic volunteers (five men and sixteen women) aged 53 to 68 | Breakfasts including 40 mL VOO with either a low (80 ppm) or high (400 ppm) polyphenolic content | Higher decrease in plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 PAI-1 activity in plasma 2 h following the high-phenol meal than after the low-phenol meal | [80] |

| Randomized, parallel, controlled clinical trial in ninety healthy subjects aged 20 to 50 | Mediterranean diet with washed virgin olive oil (WOO, 55 mg/kg) or VOO (328 mg/kg) for three months | Down-regulation of proatherogenic genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and decrease in plasma inflammatory and oxidative status and the expression of related genes | [81] |

| Randomized, crossover, and controlled study involving fifty-one healthy adults | 30 mL per day of standard VOO (124 ppm of phenolic compounds and 86 ppm of triterpenes), functional OO (487 ppm of phenolic compounds and enriched with 389 ppm of triterpenes), or optimized VOO (490 ppm of phenolic compounds and 86 ppm of triterpenes) for three weeks | Plasmatic reduction in oxidized lipids, inflammatory biomarkers (TNF-α and other cytokines), indicators of DNA damage and vascular damage | [84] |

| Randomized, controlled, double-blind crossover trial involving twenty adults (mean age 56.1 years; ten women, ten men) at risk for T2D | 50 mL of ROO without polyphenols or high-polyphenolic EVOO (single administration) | Improvement of endothelial function assessed as flow-mediated dilatation. No significant activity on diastolic or systolic blood pressure | [85] |

| Eleven overweight T2D patients | First four weeks (wash-out period) administration of ROO (polyphenols not detectable), second four weeks with EVOO (25 mL/day, 577 mg of phenolic compounds/kg) | Reduction in fasting plasma HbA1c levels and glucose as well as body weight, BMI, and serum levels of ALT and AST | [86] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serreli, G.; Boronat, A.; De la Torre, R.; Rodriguez-Moratò, J.; Deiana, M. Cardiovascular and Metabolic Benefits of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Phenolic Compounds: Mechanistic Insights from In Vivo Studies. Cells 2024, 13, 1555. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13181555

Serreli G, Boronat A, De la Torre R, Rodriguez-Moratò J, Deiana M. Cardiovascular and Metabolic Benefits of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Phenolic Compounds: Mechanistic Insights from In Vivo Studies. Cells. 2024; 13(18):1555. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13181555

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerreli, Gabriele, Anna Boronat, Rafael De la Torre, Josè Rodriguez-Moratò, and Monica Deiana. 2024. "Cardiovascular and Metabolic Benefits of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Phenolic Compounds: Mechanistic Insights from In Vivo Studies" Cells 13, no. 18: 1555. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13181555

APA StyleSerreli, G., Boronat, A., De la Torre, R., Rodriguez-Moratò, J., & Deiana, M. (2024). Cardiovascular and Metabolic Benefits of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Phenolic Compounds: Mechanistic Insights from In Vivo Studies. Cells, 13(18), 1555. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13181555