Gait Training in Virtual Reality: Short-Term Effects of Different Virtual Manipulation Techniques in Parkinson’s Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects, Clinical Data, and Questionnaires

- Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale of the Movement Disorder Society (MDS-UPDRS) part III [25] as a general motor score

- Ziegler’s freezing of gait course [27] as an objective assessment of FOG in PD

- Short, 7-item version of the Berg balance scale [28] as an objective measure of balance as a parameter of gait stability

- German version of the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA, [20], http://www.mocatest.org) as a measure of cognitive function in PD

- Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ [31]) before and after the experiment

- Slater, Usoh, and Steed Questionnaire (SUS [32]) as a measure of presence in the virtual environment

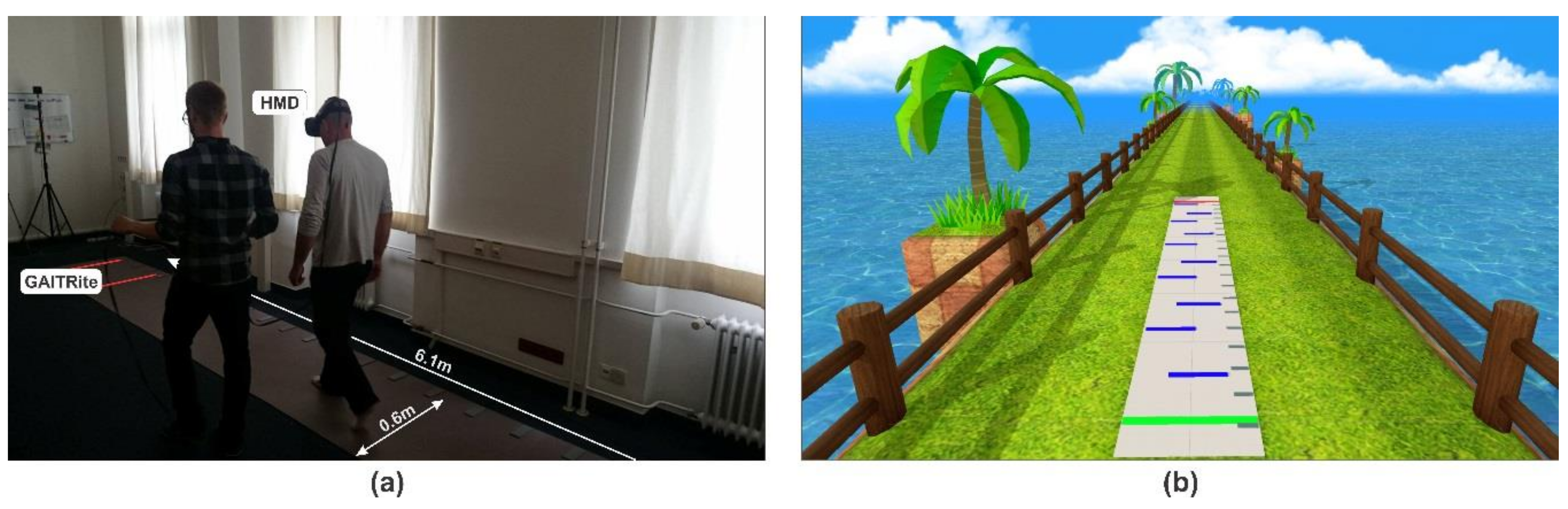

2.2. GAITRite® and Virtual Reality (VR)

2.3. Experimental Procedure

2.4. Gait Modulation Conditions

- Conditions without gait asymmetry equalization as a motor learning strategy (non-MLS): consisting of three walking conditions 1. Natural walk, 2. Walk with diving glasses to detect the influence of field of view (FOV), and 3. Walk with HTC Vive without specific gait asymmetry manipulation in VR.

- Conditions with gait asymmetry equalization as a motor learning strategy (MLS): including 4 walking conditions to assess the effects of different VR gait manipulation strategies using visual targets and proprioceptive signals on gait asymmetry and other gait parameters (see Table 2).

2.5. Gait Parameters

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Aspects

3.2. Objective Gait Parameters in Virtual Reality (VR)

3.2.1. Conditions Without Asymmetry Equalization as Motor Learning Strategy (non-MLS): Effects of Field of View and “Pure” Virtual Environment

3.2.2. Conditions With Asymmetry Equalization as Motor Learning Strategy (MLS): Effects of Different VR Gait Manipulation Conditions on Gait

3.2.3. After-Effects of VR Gait Modulation Conditions on Gait and Gait Asymmetry

3.3. Simulator Sickness and Presence

3.4. Correlations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hely, M.A.; Reid, W.G.; Adena, M.A.; Halliday, G.M.; Morris, J.G. The sydney multicenter study of parkinson’s disease: The inevitability of dementia at 20 years. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2008, 23, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudzinska, M.; Bukowczan, S.; Stozek, J.; Zajdel, K.; Mirek, E.; Chwala, W.; Wojcik-Pedziwiatr, M.; Banaszkiewicz, K.; Szczudlik, A. The incidence and risk factors of falls in parkinson disease: Prospective study. Neurol. I Neurochir. Pol. 2013, 47, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudzinska, M.; Bukowczan, S.; Stozek, J.; Zajdel, K.; Mirek, E.; Chwala, W.; Wojcik-Pedziwiatr, M.; Banaszkiewicz, K.; Szczudlik, A. Causes and consequences of falls in parkinson disease patients in a prospective study. Neurol. I Neurochir. Pol. 2013, 47, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giladi, N.; Horak, F.B.; Hausdorff, J.M. Classification of gait disturbances: Distinguishing between continuous and episodic changes. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2013, 28, 1469–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, L.; Ricciardi, D.; Lena, F.; Plotnik, M.; Petracca, M.; Barricella, S.; Bentivoglio, A.R.; Modugno, N.; Bernabei, R.; Fasano, A. Working on asymmetry in parkinson’s disease: Randomized, controlled pilot study. Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2015, 36, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausdorff, J.M. Gait dynamics in parkinson’s disease: Common and distinct behavior among stride length, gait variability, and fractal-like scaling. Chaos 2009, 19, 026113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazzitta, G.; Pezzoli, G.; Bertotti, G.; Maestri, R. Asymmetry and freezing of gait in parkinsonian patients. J. Neurol. 2013, 260, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plotnik, M.; Giladi, N.; Balash, Y.; Peretz, C.; Hausdorff, J.M. Is freezing of gait in parkinson’s disease related to asymmetric motor function? Ann. Neurol. 2005, 57, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano Porras, D.; Siemonsma, P.; Inzelberg, R.; Zeilig, G.; Plotnik, M. Advantages of virtual reality in the rehabilitation of balance and gait: Systematic review. Neurology 2018, 90, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dockx, K.; Bekkers, E.M.; Van den Bergh, V.; Ginis, P.; Rochester, L.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Mirelman, A.; Nieuwboer, A. Virtual reality for rehabilitation in parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 12, CD010760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffe, D.L.; Brown, D.A.; Pierson-Carey, C.D.; Buckley, E.L.; Lew, H.L. Stepping over obstacles to improve walking in individuals with poststroke hemiplegia. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2004, 41, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parijat, P.; Lockhart, T.E.; Liu, J. Effects of perturbation-based slip training using a virtual reality environment on slip-induced falls. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 43, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, J.; Richards, C.L.; Malouin, F.; McFadyen, B.J.; Lamontagne, A. A treadmill and motion coupled virtual reality system for gait training post-stroke. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirelman, A.; Maidan, I.; Herman, T.; Deutsch, J.E.; Giladi, N.; Hausdorff, J.M. Virtual reality for gait training: Can it induce motor learning to enhance complex walking and reduce fall risk in patients with parkinson’s disease? J. Gerontol. Ser. Abiol. Sci. Med Sci. 2011, 66, 234–240. [Google Scholar]

- Ehgoetz Martens, K.A.; Shine, J.M.; Walton, C.C.; Georgiades, M.J.; Gilat, M.; Hall, J.M.; Muller, A.J.; Szeto, J.Y.Y.; Lewis, S.J.G. Evidence for subtypes of freezing of gait in parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2018, 33, 1174–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, A.; Herzog, J.; Seifert, E.; Stolze, H.; Falk, D.; Reese, R.; Volkmann, J.; Deuschl, G. Modulation of gait coordination by subthalamic stimulation improves freezing of gait. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2011, 26, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, A.; Schlenstedt, C.; Herzog, J.; Plotnik, M.; Rose, F.E.M.; Volkmann, J.; Deuschl, G. Split-belt locomotion in parkinson’s disease links asymmetry, dyscoordination and sequence effect. Gait Posture 2016, 48, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.J.; Daniel, S.E.; Kilford, L.; Lees, A.J. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic parkinson’s disease: A clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1992, 55, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehn, M.M.; Yahr, M.D. Parkinsonism: Onset, progression, and mortality. Neurology 1967, 57, S11–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bedirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The montreal cognitive assessment, moca: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, E.J.; Chu, H.; Gaunt, D.M.; Whone, A.L.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Lyell, V. Comparison of test your memory and montreal cognitive assessment measures in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s Dis. 2016, 2016, 1012847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.; Funk, M.; Crossley, M.; Basran, J.; Kirk, A.; Dal Bello-Haas, V. The potential of gait analysis to contribute to differential diagnosis of early stage dementia: Current research and future directions. Can. J. Aging 2007, 26, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giladi, N.; Shabtai, H.; Simon, E.S.; Biran, S.; Tal, J.; Korczyn, A.D. Construction of freezing of gait questionnaire for patients with parkinsonism. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2000, 6, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Martin, D.; Sama, A.; Perez-Lopez, C.; Catala, A.; Moreno Arostegui, J.M.; Cabestany, J.; Bayes, A.; Alcaine, S.; Mestre, B.; Prats, A.; et al. Home detection of freezing of gait using support vector machines through a single waist-worn triaxial accelerometer. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171764. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz, C.G.; Tilley, B.C.; Shaftman, S.R.; Stebbins, G.T.; Fahn, S.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Poewe, W.; Sampaio, C.; Stern, M.B.; Dodel, R.; et al. Movement disorder society-sponsored revision of the unified parkinson’s disease rating scale (mds-updrs): Scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2008, 23, 2129–2170. [Google Scholar]

- Vogler, A.; Janssens, J.; Nyffeler, T.; Bohlhalter, S.; Vanbellingen, T. German translation and validation of the “freezing of gait questionnaire” in patients with parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s Dis. 2015, 2015, 982058. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, K.; Schroeteler, F.; Ceballos-Baumann, A.O.; Fietzek, U.M. A new rating instrument to assess festination and freezing gait in parkinsonian patients. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2010, 25, 1012–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, C.Y.; Chien, C.W.; Hsueh, I.P.; Sheu, C.F.; Wang, C.H.; Hsieh, C.L. Developing a short form of the berg balance scale for people with stroke. Phys. Ther. 2006, 86, 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson, C.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Peto, V.; Greenhall, R.; Hyman, N. The parkinson’s disease questionnaire (pdq-39): Development and validation of a parkinson’s disease summary index score. Age Ageing 1997, 26, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, K.; Broll, S.; Winkelmann, J.e.a. Untersuchung zur reliabilität der deutschen version des pdq-39: Ein krankheitsspezifischer fragebogen zur erfassung der lebensqualität von parkinson-patienten. Akt Neurol. 1999, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.L.; Berbaum, K.S.; Lilienthal, M.G. Simulator sickness questionnaire: An enhanced method for quantifying simulator sickness. Int. J. Aviat. Psychol. 1993, 3, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M; Usoh, M.; Steed, A. Depth of presence in virtual environments. Presence 1994, 3, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.J. Gaitrite Operating Manual; CIR Systems, Inc.: Havertown, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, K.K.; Gage, W.H.; Brooks, D.; Black, S.E.; McIlroy, W.E. Evaluation of gait symmetry after stroke: A comparison of current methods and recommendations for standardization. Gait Posture 2010, 31, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, M.S.; Rintala, D.H.; Hou, J.G.; Charness, A.L.; Fernandez, A.L.; Collins, R.L.; Baker, J.; Lai, E.C.; Protas, E.J. Gait variability in parkinson’s disease: Influence of walking speed and dopaminergic treatment. Neurol. Res. 2011, 33, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchet, O.; Annweiler, C.; Lecordroch, Y.; Allali, G.; Dubost, V.; Herrmann, F.R.; Kressig, R.W. Walking speed-related changes in stride time variability: Effects of decreased speed. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2009, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretz, H.R.; Doering, L.L.; Quinn, J.; Raftopoulos, M.; Nelson, A.J.; Zwick, D.E. Functional ambulation performance testing of adults with down syndrome. NeuroRehabilitation 1998, 11, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Taylor & Francis Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ehgoetz Martens, K.A.; Ellard, C.G.; Almeida, Q.J. Does anxiety cause freezing of gait in parkinson’s disease? PloS ONE 2014, 9, e106561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janeh, O.; Langbehn, E.; Steinicke, F.; Bruder, G.; Gulberti, A.; Poetter-Nerger, M. Walking in virtual reality: Effects of manipulated visual self-motion on walking biomechanics. Acm Trans. Appl. Percept. 2010, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeh, O.; Bruder, G.; Steinicke, F.; Gulberti, A.; Poetter-Nerger, M. Analyses of gait parameters of younger and older adults during (non-)isometric virtual walking. Ieee Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2018, 24, 2663–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Darakjian, N.; Finley, J.M. Walking in fully immersive virtual environments: An evaluation of potential adverse effects in older adults and individuals with parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2017, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebersbach, G.; Ebersbach, A.; Edler, D.; Kaufhold, O.; Kusch, M.; Kupsch, A.; Wissel, J. Comparing exercise in parkinson’s disease—The berlin lsvt(r)big study. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 1902, 25, 1902–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.S.; Horak, F.B. Neural control of walking in people with parkinsonism. Physiology 2016, 31, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisman, D.S.; Wityk, R.; Silver, K.; Bastian, A.J. Locomotor adaptation on a split-belt treadmill can improve walking symmetry post-stroke. Brain A J. Neurol. 2007, 130, 1861–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisman, D.S.; McLean, H.; Keller, J.; Danks, K.A.; Bastian, A.J. Repeated split-belt treadmill training improves poststroke step length asymmetry. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2013, 27, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Palmer, C.J.; Hohwy, J.; Youssef, G.J.; Paton, B.; Tsuchiya, N.; Stout, J.C.; Thyagarajan, D. Parkinson’s disease alters multisensory perception: Insights from the rubber hand illusion. Neuropsychologia 2017, 97, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano Porras, D.; Plotnik, M.; Inzelberg, R.; Zeilig, G. Gait adaptation to conflictive visual flow in virtual environments. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Virtual Rehabilitation (ICVR), Montreal, QC, Canada, 19–22 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, H.; O’Connor, D.P.; Lee, B.C.; Layne, C.S.; Gorniak, S.L. Alterations in over-ground walking patterns in obese and overweight adults. Gait Posture 2017, 53, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.E.; Iansek, R.; Matyas, T.A.; Summers, J.J. Stride length regulation in parkinson’s disease. Normalization strategies and underlying mechanisms. Brain 1996, 119, 551–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

= significant difference between short and long side

= significant difference between short and long side  = significant difference between different gait modulations conditions for short and long sides

= significant difference between different gait modulations conditions for short and long sides  = significant difference between gait modulations conditions for either the short or the long side.

= significant difference between gait modulations conditions for either the short or the long side.

= significant difference between short and long side

= significant difference between short and long side  = significant difference between different gait modulations conditions for short and long sides

= significant difference between different gait modulations conditions for short and long sides  = significant difference between gait modulations conditions for either the short or the long side.

= significant difference between gait modulations conditions for either the short or the long side.

| Patient Characteristics and Clinical Data | Mean ± SD (min–max) |

|---|---|

| Age | 67.6 years ± 7 (49–77) |

| Gender | 15 male |

| Handedness | 1 ambidextrous, 14 right handed |

| Hoehn & Yahr Scale | 2–3 |

| Levodopa (Minutes After Intake) | 58.3 minutes ± 19.8 (40–120) |

| Leg Length | Left: 93.8cm ± 3.7 (88–102cm) Right: 93.7cm ± 4.0 (88–102cm) Leg with shorter step length: 93.7 cm ± 4.0 (89–102 cm) Leg with longer step length: 93.8 cm ± 3.8 (88–102 cm) |

| Onset of PD Symptoms | 11.5 years ± 4.9 (2–19) |

| PD Diagnosis | 9.5 years ± 4.9 (1–17) |

| Onset of Gait Disturbance | 5.5 years ± 4.4 (1–17) |

| MDS-UPDRS part III | 25.5 ± 7.2 (12–37) |

| Giladi’s FOG | 27.5 ± 10.6 (12–47) |

| Berg Balance | 24.7 ± 1.8 (19–26) |

| Ziegler’s FOG | 7.2 ± 5.9 (0–17) |

| MoCA | 27.5 ± 2.0 (23–31) |

| Pre-SSQ | 16.45 ± 16.59 (3.74–52.36) |

| Post-SSQ | 15.21 ± 17.04 (3.74–56.1) |

| SUS | 3.5 ± 0.8 (1–5.83) |

| PDQ-39 | 25.31 ± 12.83 (5.76–45.21) |

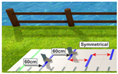

| Condition | Specification | Hypothesis and Purpose | Example (Step Length) | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Non-MLS conditions | ||||

| (1) Real World Natural Walk (“Baseline“) | Walking naturally on the GAITRite® pad without glasses * * The glasses were reversed and positioned on the participants’ head to ensure the same weight and posture during each condition | Baseline measurement | Step length of the longer side: 60 cm Step length of the shorter side: 54 cm | - |

| (2) Real World Natural Walk with Diving Glasses (“Diving Glasses”) | Walking naturally on the GAITRite® pad with diving glasses * * The diving glasses had a similar weight and field of view compared to the HTC Vive® | To detect a possible impact of a peripheral limitation of the participants’ field of view on gait, e.g., gait instability or slowing down of gait. | Step length of the longer side: 60 cm * Step length of the shorter side: 54 cm * * optimally, gait parameters should not be affected by the diving glasses | |

| (3) Natural Walk in Virtual Reality without visual targets (“Real Virtual”) | Walking naturally on the GAITRite® pad with HTC Vive 3D glasses presenting the virtual environment without visual targets | To detect possible influences of the virtual environment on gait, e.g., gait stability | Step length of the longer side: 60 cm * Step length of the shorter side: 54 cm * * Optimally, gait parameters should not be affected by the 3D glasses |  |

| B. MLS conditions | ||||

| (4) Walking in Virtual Reality with symmetric setup without presenting the feet(“Symmetrical without feet”) | Walking on the GAITRite® pad with HTC Vive 3D glasses. Lines are presented each with a distance (d) that corresponds to the individuals’ step length of the longer side - there are no feet presented on the screen. Distance = step length of the longer side – step length of the shorter side (d= SLl – SLs) New step length = old step length + distance (SLs_new = SLs_old + d) | Participants are asked to step on the lines, but walk at the natural speed. To evaluate if the visual target signals might lead to greater gait symmetry. | Step length of the longer side: 60 cm * Step length of the shorter side: 60 cm * * optimally, step length of the shorter side should adapt to that of the longer leg |  |

| (5) Walking in Virtual Reality with a symmetric setup while presenting the feet (“Symmetrical with feet”) | Walking on the GAITRite® pad with HTC Vive 3D glasses. Lines are presented each with a distance that corresponds to the individuals’ step length of the longer leg - two feet are presented on the screen. Distance = step length of the longer side – step length of the shorter side (d = SLl − SLs) New step length = old step length + distance (SLs_new = SLs_old + d) | Participants are asked to step on the lines with the middle of their feet, but walk as normal as possible while remaining in the middle of the pad. To evaluate if multiple visual signals (target and proprioceptive signals) might influence gait symmetry. | Step length of the longer side: 60 cm * Step length of the shorter side: 60 cm * * optimally, step length of the shorter leg should adapt to that of the longer leg |  |

| (6) Walking in Virtual Reality with an asymmetric setup while presenting the feet (“Asymmetrical with feet”) | Walking on the GAITRite® pad with HTC Vive 3D glasses. Lines are presented with asymmetrical distances: Step length of shorter leg (SLs) is exaggerated: New step length = step length of the shorter side + (2* (step length of the longer side – step length of the shorter side) (SLs_new = SLs+ (2*(SLI-SLs))) 2 feet are presented on the screen moving kinematically similar to the participants feet | Participants are asked to step on the lines with the middle of their feet, but walk as normal as possible while remaining in the middle of the pad. To evaluate if an exaggeration of step lengths of the shorter leg is needed to achieve gait symmetry. | New step length of the shorter side: 66 cm Step length of the longer side: 60 cm * * optimally, step length of the shorter leg should adapt to that of the longer leg |  |

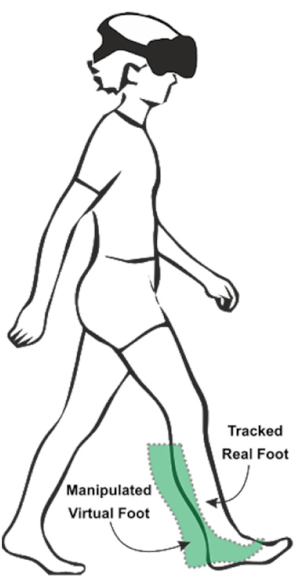

| (7) Walking in Virtual Reality with a symmetric setup while manipulating the feet of the shorter side (“visual-proprioceptive dissociation”) | Walking on the GAITRite® pad with HTC Vive 3D glasses. Lines are presented with a distance that corresponds to the individuals’ step length of the longer leg. Two feet are presented on the screen. However, the foot on the shorter side is visually shifted backwards. Shift of the manipulated virtual foot = step length of the longer side – step length of the shorter side (Shift_m = SLI-SLs) | To evaluate if a visual shifting of the proprioceptive signal leads to a greater gait symmetry. | Distance between lines: 60 cm Shift: 6 cm Step length of the longer side: 60 cm * Step length of the shorter side: 60 cm * * Optimally, step length of the shorter side should adapt to that of the longer side. |  |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Janeh, O.; Fründt, O.; Schönwald, B.; Gulberti, A.; Buhmann, C.; Gerloff, C.; Steinicke, F.; Pötter-Nerger, M. Gait Training in Virtual Reality: Short-Term Effects of Different Virtual Manipulation Techniques in Parkinson’s Disease. Cells 2019, 8, 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8050419

Janeh O, Fründt O, Schönwald B, Gulberti A, Buhmann C, Gerloff C, Steinicke F, Pötter-Nerger M. Gait Training in Virtual Reality: Short-Term Effects of Different Virtual Manipulation Techniques in Parkinson’s Disease. Cells. 2019; 8(5):419. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8050419

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaneh, Omar, Odette Fründt, Beate Schönwald, Alessandro Gulberti, Carsten Buhmann, Christian Gerloff, Frank Steinicke, and Monika Pötter-Nerger. 2019. "Gait Training in Virtual Reality: Short-Term Effects of Different Virtual Manipulation Techniques in Parkinson’s Disease" Cells 8, no. 5: 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8050419

APA StyleJaneh, O., Fründt, O., Schönwald, B., Gulberti, A., Buhmann, C., Gerloff, C., Steinicke, F., & Pötter-Nerger, M. (2019). Gait Training in Virtual Reality: Short-Term Effects of Different Virtual Manipulation Techniques in Parkinson’s Disease. Cells, 8(5), 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8050419