PPM1A Controls Diabetic Gene Programming through Directly Dephosphorylating PPARγ at Ser273

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Expression Plasmids and RNA Interference

2.3. Lentivirus Production and Infection

2.4. Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

2.5. In Vitro Phosphatase Assay

2.6. Dot Blot Assay

2.7. Subcellular Fractionation

2.8. In Vitro Insulin-Resistance (IR) Model

2.9. Real-Time RT-PCR (Quantitative PCR, qPCR)

2.10. Correlation Analysis in Human Adipose Tissues

2.11. Animals

3. Results

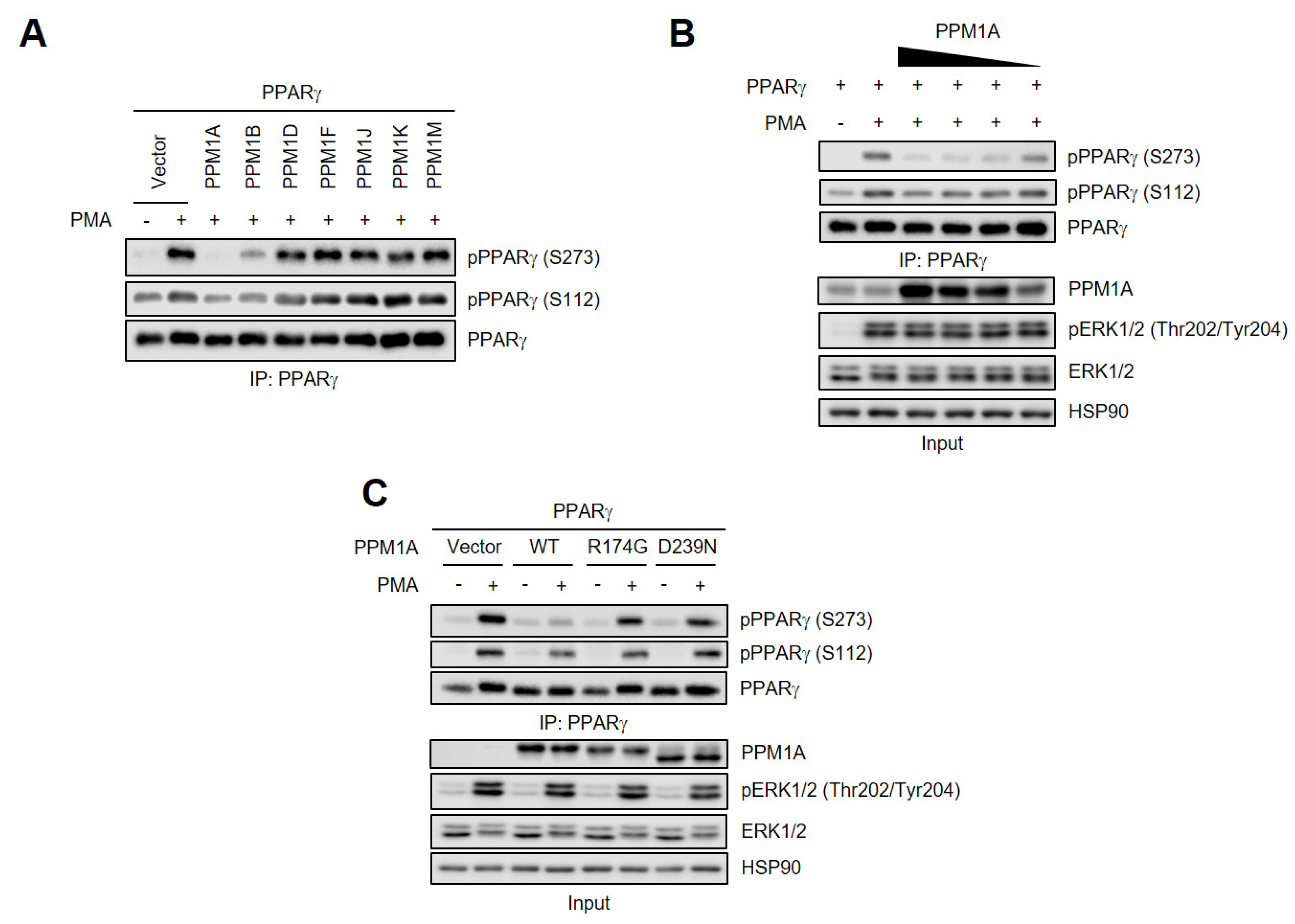

3.1. PPM1A is a Phosphatase that Acts on PPARγ

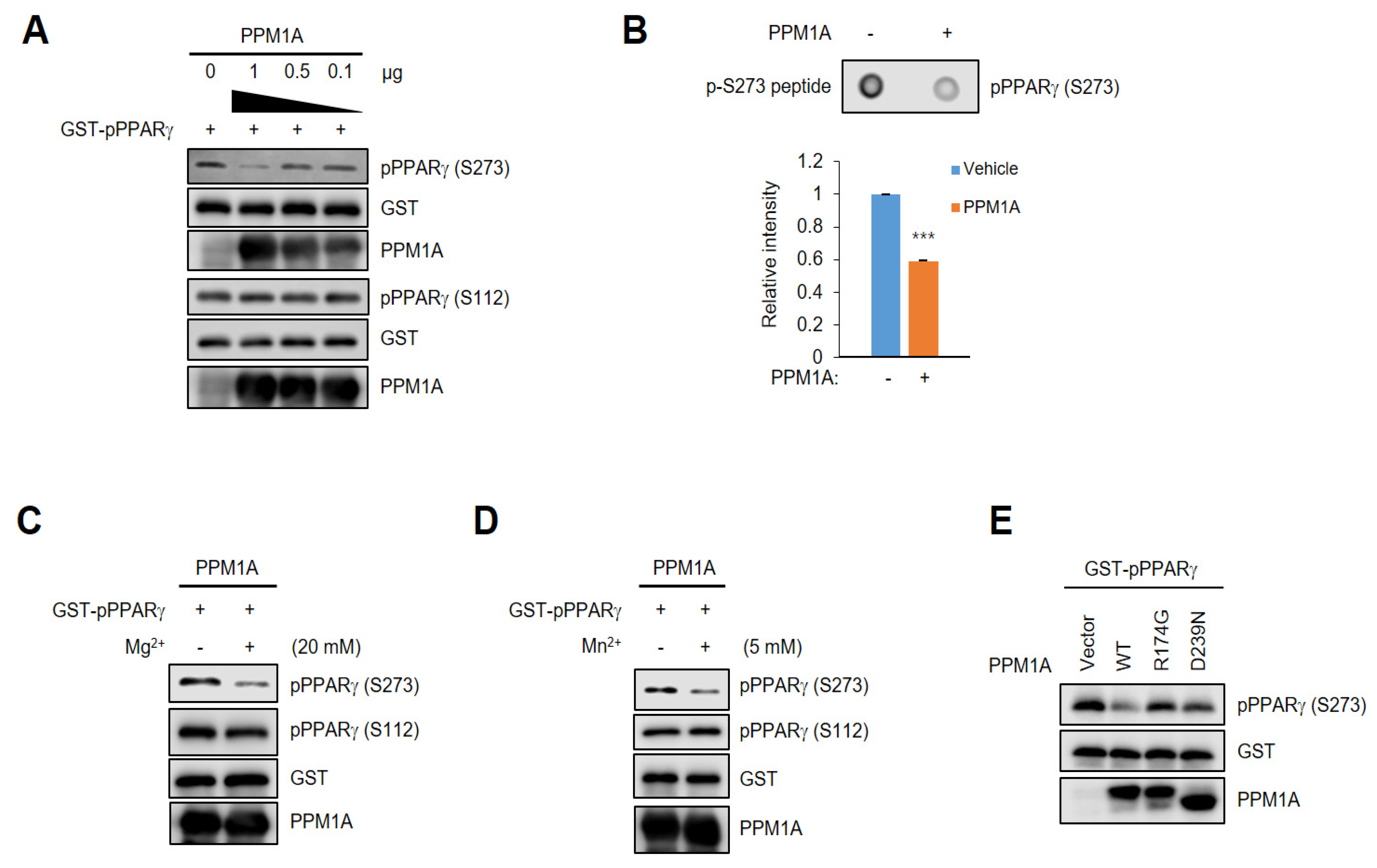

3.2. PPM1A Directly Dephosphorylates PPARγ at Ser273 but not Ser112

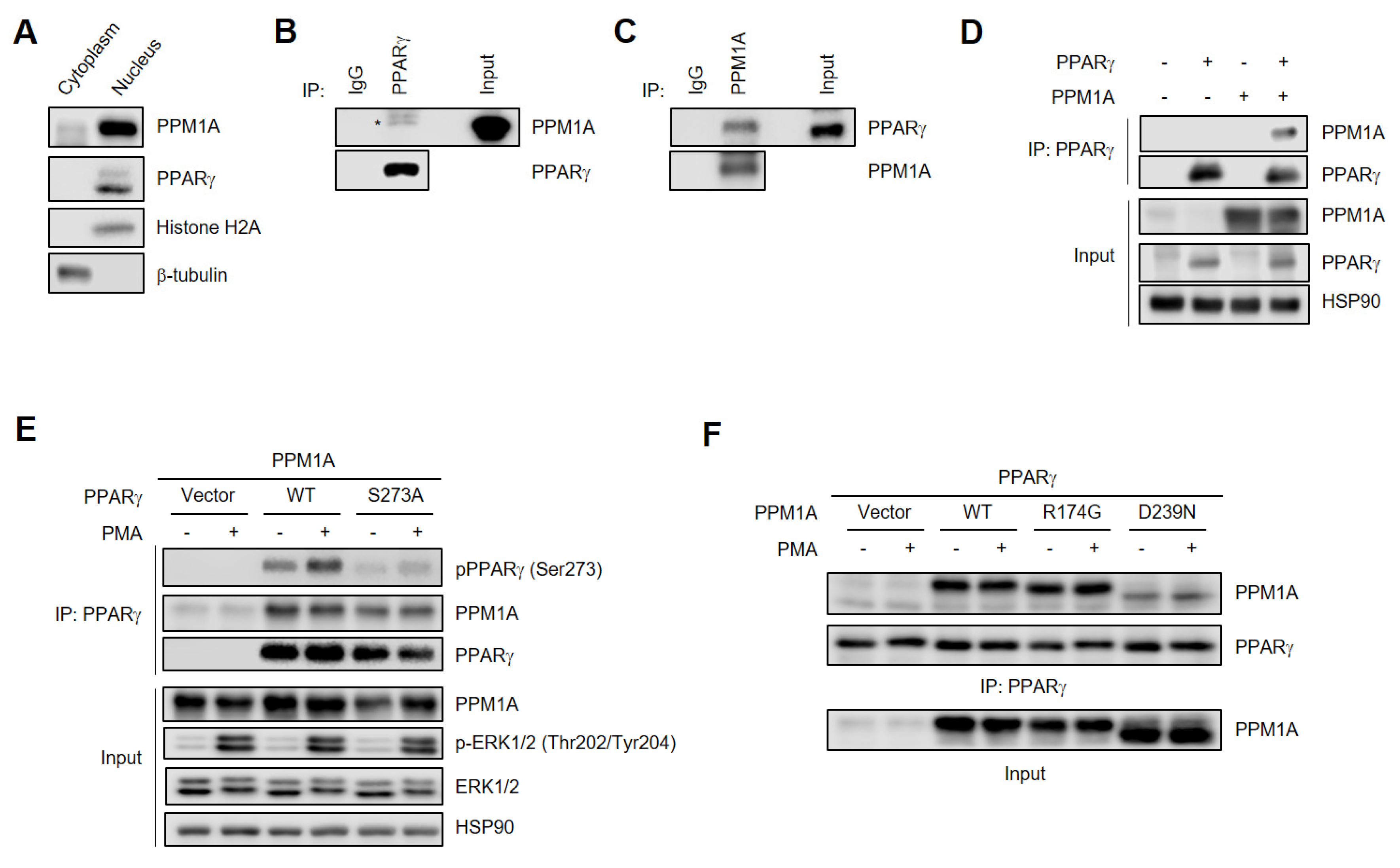

3.3. PPM1A Physically Interacts with PPARγ

3.4. PPM1A Specifically Regulates the Expression of a Diabetic Gene Set that is Dysregulated by pSer273

3.5. Knockdown of PPM1A Devastates Insulin Resistant Status in Adipocytes

3.6. PPM1A is Negatively Correlated with pSer273

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spiegelman, B.M.; Flier, J.S. Adipogenesis and obesity: Rounding out the big picture. Cell 1996, 87, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kusminski, C.M.; Bickel, P.E.; Scherer, P.E. Targeting adipose tissue in the treatment of obesity-associated diabetes. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 639–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gaal, L.F.; Mertens, I.L.; De Block, C.E. Mechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular disease. Nature 2006, 444, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes. Res. 1998, 6 Suppl 2, 51S–209S.

- Kershaw, E.E.; Flier, J.S. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 2548–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, M.E.; Scherer, P.E. Adipose tissue-derived factors: Impact on health and disease. Endocr. Rev. 2006, 27, 762–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sharma, A.M.; Staels, B. Review: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and adipose tissue--understanding obesity-related changes in regulation of lipid and glucose metabolism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 2000, 894, 1–253.

- Jung, U.J.; Choi, M.S. Obesity and its metabolic complications: The role of adipokines and the relationship between obesity, inflammation, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 6184–6223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balistreri, C.R.; Caruso, C.; Candore, G. The role of adipose tissue and adipokines in obesity-related inflammatory diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2010, 2010, 802078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil, G.S.; Shargill, N.S.; Spiegelman, B.M. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: Direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science 1993, 259, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagathu, C.; Yvan-Charvet, L.; Bastard, J.P.; Maachi, M.; Quignard-Boulange, A.; Capeau, J.; Caron, M. Long-term treatment with interleukin-1beta induces insulin resistance in murine and human adipocytes. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 2162–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rull, A.; Camps, J.; Alonso-Villaverde, C.; Joven, J. Insulin resistance, inflammation, and obesity: Role of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (or CCL2) in the regulation of metabolism. Mediators Inflamm. 2010, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berg, A.H.; Combs, T.P.; Du, X.; Brownlee, M.; Scherer, P.E. The adipocyte-secreted protein Acrp30 enhances hepatic insulin action. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.; Liang, P.; Spiegelman, B.M. AdipoQ is a novel adipose-specific gene dysregulated in obesity. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 10697–10703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamauchi, T.; Kamon, J.; Waki, H.; Terauchi, Y.; Kubota, N.; Hara, K.; Mori, Y.; Ide, T.; Murakami, K.; Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N.; et al. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, B.S.; Cook, K.S.; Yaglom, J.; Groves, D.L.; Volanakis, J.E.; Damm, D.; White, T.; Spiegelman, B.M. Adipsin and complement factor D activity: An immune-related defect in obesity. Science 1989, 244, 1483–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, M.; Suh, J.M.; Hah, N.; Liddle, C.; Atkins, A.R.; Downes, M.; Evans, R.M. PPARgamma signaling and metabolism: The good, the bad and the future. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, R.M.; Barish, G.D.; Wang, Y.X. PPARs and the complex journey to obesity. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tontonoz, P.; Spiegelman, B.M. Fat and beyond: The diverse biology of PPARgamma. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008, 77, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R.F.; Farmer, S.R. Hormonal signaling and transcriptional control of adipocyte differentiation. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 3116S–3121S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tontonoz, P.; Hu, E.; Spiegelman, B.M. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPAR gamma 2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell 1994, 79, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willson, T.M.; Lambert, M.H.; Kliewer, S.A. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and metabolic disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001, 70, 341–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, J.M.; Moore, L.B.; Smith-Oliver, T.A.; Wilkison, W.O.; Willson, T.M.; Kliewer, S.A. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR gamma). J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 12953–12956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, S.S.; Park, J.; Choi, J.H. Revisiting PPARgamma as a target for the treatment of metabolic disorders. BMB Rep. 2014, 47, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, S.H.; Chung, S.S.; Park, K.S. Re-highlighting the action of PPARgamma in treating metabolic diseases. F1000Res 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, E.; Kim, J.B.; Sarraf, P.; Spiegelman, B.M. Inhibition of adipogenesis through MAP kinase-mediated phosphorylation of PPARgamma. Science 1996, 274, 2100–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, J.H.; Banks, A.S.; Estall, J.L.; Kajimura, S.; Bostrom, P.; Laznik, D.; Ruas, J.L.; Chalmers, M.J.; Kamenecka, T.M.; Bluher, M.; et al. Anti-diabetic drugs inhibit obesity-linked phosphorylation of PPARgamma by Cdk5. Nature 2010, 466, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banks, A.S.; McAllister, F.E.; Camporez, J.P.; Zushin, P.J.; Jurczak, M.J.; Laznik-Bogoslavski, D.; Shulman, G.I.; Gygi, S.P.; Spiegelman, B.M. An ERK/Cdk5 axis controls the diabetogenic actions of PPARgamma. Nature 2015, 517, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hinds, T.D., Jr.; Stechschulte, L.A.; Cash, H.A.; Whisler, D.; Banerjee, A.; Yong, W.; Khuder, S.S.; Kaw, M.K.; Shou, W.; Najjar, S.M.; et al. Protein phosphatase 5 mediates lipid metabolism through reciprocal control of glucocorticoid receptor and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARgamma). J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 42911–42922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tasdelen, I.; van Beekum, O.; Gorbenko, O.; Fleskens, V.; van den Broek, N.J.; Koppen, A.; Hamers, N.; Berger, R.; Coffer, P.J.; Brenkman, A.B.; et al. The serine/threonine phosphatase PPM1B (PP2Cbeta) selectively modulates PPARgamma activity. Biochem. J. 2013, 451, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, D.; Zhang, L.; Xu, L.; Liu, L.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhao, T.; Wu, L.; Zhao, Y.; et al. WIP1 phosphatase is a critical regulator of adipogenesis through dephosphorylating PPARgamma serine 112. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 2067–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjeld, C.C.; Denu, J.M. Kinetic analysis of human serine/threonine protein phosphatase 2Calpha. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 20336–20343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jackson, M.D.; Fjeld, C.C.; Denu, J.M. Probing the function of conserved residues in the serine/threonine phosphatase PP2Calpha. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 8513–8521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barford, D. Molecular mechanisms of the protein serine/threonine phosphatases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1996, 21, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Helps, N.R.; Cohen, P.T.; Barford, D. Crystal structure of the protein serine/threonine phosphatase 2C at 2.0 A resolution. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 6798–6809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lammers, T.; Lavi, S. Role of type 2C protein phosphatases in growth regulation and in cellular stress signaling. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007, 42, 437–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Duan, X.; Liang, Y.Y.; Su, Y.; Wrighton, K.H.; Long, J.; Hu, M.; Davis, C.M.; Wang, J.; Brunicardi, F.C.; et al. PPM1A functions as a Smad phosphatase to terminate TGFbeta signaling. Cell 2006, 125, 915–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lo, K.A.; Labadorf, A.; Kennedy, N.J.; Han, M.S.; Yap, Y.S.; Matthews, B.; Xin, X.; Sun, L.; Davis, R.J.; Lodish, H.F.; et al. Analysis of in vitro insulin-resistance models and their physiological relevance to in vivo diet-induced adipose insulin resistance. Cell Rep. 2013, 5, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rocca-Serra, P.; Brazma, A.; Parkinson, H.; Sarkans, U.; Shojatalab, M.; Contrino, S.; Vilo, J.; Abeygunawardena, N.; Mukherjee, G.; Holloway, E.; et al. ArrayExpress: A public database of gene expression data at EBI. C R Biol. 2003, 326, 1075–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Choi, S.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Khim, K.W.; Yoon, S.; Kim, B.G.; Nam, D.; Suh, P.G.; Myung, K.; Choi, J.H. The E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM25 regulates adipocyte differentiation via proteasome-mediated degradation of PPARgamma. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mazur, S.J.; Gallagher, E.S.; Debnath, S.; Durell, S.R.; Anderson, K.W.; Miller Jenkins, L.M.; Appella, E.; Hudgens, J.W. Conformational Changes in Active and Inactive States of Human PP2Calpha Characterized by Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange-Mass Spectrometry. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 2676–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Choi, J.H.; Banks, A.S.; Kamenecka, T.M.; Busby, S.A.; Chalmers, M.J.; Kumar, N.; Kuruvilla, D.S.; Shin, Y.; He, Y.; Bruning, J.B.; et al. Antidiabetic actions of a non-agonist PPARgamma ligand blocking Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation. Nature 2011, 477, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.S.; Kim, E.S.; Koh, M.; Lee, S.J.; Lim, D.; Yang, Y.R.; Jang, H.J.; Seo, K.A.; Min, S.H.; Lee, I.H.; et al. A novel non-agonist peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) ligand UHC1 blocks PPARgamma phosphorylation by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5) and improves insulin sensitivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 26618–26629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, S.S.; Kim, E.S.; Jung, J.E.; Marciano, D.P.; Jo, A.; Koo, J.Y.; Choi, S.Y.; Yang, Y.R.; Jang, H.J.; Kim, E.K.; et al. PPARgamma Antagonist Gleevec Improves Insulin Sensitivity and Promotes the Browning of White Adipose Tissue. Diabetes 2016, 65, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iankova, I.; Petersen, R.K.; Annicotte, J.S.; Chavey, C.; Hansen, J.B.; Kratchmarova, I.; Sarruf, D.; Benkirane, M.; Kristiansen, K.; Fajas, L. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma recruits the positive transcription elongation factor b complex to activate transcription and promote adipogenesis. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006, 20, 1494–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compe, E.; Drane, P.; Laurent, C.; Diderich, K.; Braun, C.; Hoeijmakers, J.H.; Egly, J.M. Dysregulation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor target genes by XPD mutations. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 25, 6065–6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pondugula, S.R.; Flannery, P.C.; Apte, U.; Babu, J.R.; Geetha, T.; Rege, S.D.; Chen, T.; Abbott, K.L. Mg2+/Mn2+-dependent phosphatase 1A is involved in regulating pregnane X receptor-mediated cytochrome p450 3A4 gene expression. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2015, 43, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, Y. Serine/threonine phosphatases: Mechanism through structure. Cell 2009, 139, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, G.; Wang, Y. Functional diversity of mammalian type 2C protein phosphatase isoforms: New tales from an old family. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2008, 35, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Kusminski, C.M.; Scherer, P.E. Adipose tissue remodeling and obesity. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 2094–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Castoldi, A.; Naffah de Souza, C.; Camara, N.O.; Moraes-Vieira, P.M. The Macrophage Switch in Obesity Development. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lumeng, C.N.; DelProposto, J.B.; Westcott, D.J.; Saltiel, A.R. Phenotypic switching of adipose tissue macrophages with obesity is generated by spatiotemporal differences in macrophage subtypes. Diabetes 2008, 57, 3239–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boutens, L.; Stienstra, R. Adipose tissue macrophages: Going off track during obesity. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 879–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nishimura, S.; Manabe, I.; Nagai, R. Adipose tissue inflammation in obesity and metabolic syndrome. Discov. Med. 2009, 8, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Stolarczyk, E. Adipose tissue inflammation in obesity: A metabolic or immune response? Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2017, 37, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, S.M.; Saltiel, A.R. Adapting to obesity with adipose tissue inflammation. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluher, M. Adipose tissue inflammation: A cause or consequence of obesity-related insulin resistance? Clin. Sci. (Lond) 2016, 130, 1603–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.R.; Schaaf, K.; Rajabalee, N.; Wagner, F.; Duverger, A.; Kutsch, O.; Sun, J. The phosphatase PPM1A controls monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, W.; Yu, Y.; Dotti, G.; Shen, T.; Tan, X.; Savoldo, B.; Pass, A.K.; Chu, M.; Zhang, D.; Lu, X.; et al. PPM1A and PPM1B act as IKKbeta phosphatases to terminate TNFalpha-induced IKKbeta-NF-kappaB activation. Cell Signal. 2009, 21, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barbagallo, M.; Dominguez, L.J. Magnesium and type 2 diabetes. World J. Diabetes 2015, 6, 1152–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hassan, S.A.U.; Ahmed, I.; Nasrullah, A.; Haq, S.; Ghazanfar, H.; Sheikh, A.B.; Zafar, R.; Askar, G.; Hamid, Z.; Khushdil, A.; et al. Comparison of Serum Magnesium Levels in Overweight and Obese Children and Normal Weight Children. Cureus 2017, 9, e1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jahnen-Dechent, W.; Ketteler, M. Magnesium basics. Clin. Kidney J. 2012, 5, i3–i14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Romani, A.M. Cellular magnesium homeostasis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011, 512, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, W.; Zhu, X.; Song, Y.; Fan, L.; Wu, L.; Kabagambe, E.K.; Hou, L.; Shrubsole, M.J.; Liu, J.; Dai, Q. Intakes of magnesium, calcium and risk of fatty liver disease and prediabetes. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 2088–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lipner, A. Symptomatic magnesium deficiency after small-intestinal bypass for obesity. Br. Med. J. 1977, 1, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bertinato, J.; Lavergne, C.; Rahimi, S.; Rachid, H.; Vu, N.A.; Plouffe, L.J.; Swist, E. Moderately Low Magnesium Intake Impairs Growth of Lean Body Mass in Obese-Prone and Obese-Resistant Rats Fed a High-Energy Diet. Nutrients 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, B.; Lawson, A.B.; Liese, A.D.; Bell, R.A.; Mayer-Davis, E.J. Dairy, magnesium, and calcium intake in relation to insulin sensitivity: Approaches to modeling a dose-dependent association. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 164, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, J.; Folsom, A.R.; Melnick, S.L.; Eckfeldt, J.H.; Sharrett, A.R.; Nabulsi, A.A.; Hutchinson, R.G.; Metcalf, P.A. Associations of serum and dietary magnesium with cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, insulin, and carotid arterial wall thickness: The ARIC study. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1995, 48, 927–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, H.; Wanner, C. Magnesium in disease. Clin. Kidney J. 2012, 5, i25–i38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, D.S.; Puntel, R.L.; Aschner, M. Manganese in health and disease. Met. Ions Life Sci. 2013, 13, 199–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khairi, T.; Amer, S.; Spitalewitz, S.; Alasadi, L. Severe Symptomatic Hypermagnesemia Associated with Over-the-Counter Laxatives in a Patient with Renal Failure and Sigmoid Volvulus. Case Rep. Nephrol. 2014, 2014, 560746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bowman, A.B.; Kwakye, G.F.; Herrero Hernandez, E.; Aschner, M. Role of manganese in neurodegenerative diseases. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2011, 25, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Affymetrix ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Name | log2 FC (vs. Lean Healthy) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16784909 | Ppm1a | Protein phosphatase, Mg2+/Mn2+ dependent, 1A | –0.02583 | 0.004725 ** |

| 17117110 | Cd24a | CD24 molecule, type A | –0.03623 | 0.291983 |

| 16669796 | Txnip | Thioredoxin interacting protein | –0.02935 | 0.005334 ** |

| 16844294 | Nr1d1 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group D member 1 | 0.054739 | 0.042975 * |

| 16733435 | Aplp2 | Amyloid beta precursor like protein 2 | 0.012981 | 0.048507 * |

| 17048563 | Peg10 | Paternally expressed 10 | 0.158202 | 0.018165 * |

| 16852660 | Acyl | ATP citrate lyase | −0.10524 | 0.037731 * |

| 16950609 | Cidec | Cell death inducing DFFA like effector C | −0.04005 | 0.000383 *** |

| 17001100 | Nr3c1 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 3 group C member 1 | −0.07386 | 0.000149 *** |

| 17064251 | Rarres2 | Retinoic acid receptor responder 2 | −0.08898 | 0.011576 * |

| 17070441 | Car3 | Carbonic anhydrase 3 | −0.394 | 0.001141 ** |

| 16693082 | Selenbp1 | Selenium binding protein 1 | −0.04191 | 0.034659 * |

| 16938378 | Nr1d2 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group D member 2 | −0.02497 | 0.070348 |

| 16935042 | Ddx17 | DEAD-box helicase 17 | −0.00854 | 0.177737 |

| 16956244 | Rybp | RING1 And YY1 binding protein | 0.002819 | 0.427001 |

| 16949397 | Adipoq | Adiponectin, C1Q annd collagen domain containing | −0.02938 | 0.000331 *** |

| 16856299 | Cfd | Complement factor D, adipsin | 0.00749 | 0.227859 |

| 16830343 | Slc2a4 | Solute carrier family 2 member 4, GLUT4 | −0.46174 | 1.4 × 10−7 *** |

| 17001763 | Tnf | Tumor necrosis factor | 0.055804 | 2.1 × 10−5 **** |

| 16833204 | Ccl2 | C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 | 0.364464 | 4.52 × 10−5 **** |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khim, K.W.; Choi, S.S.; Jang, H.-J.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, E.; Hyun, J.-M.; Eom, H.-J.; Yoon, S.; Choi, J.-W.; Park, T.-E.; et al. PPM1A Controls Diabetic Gene Programming through Directly Dephosphorylating PPARγ at Ser273. Cells 2020, 9, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9020343

Khim KW, Choi SS, Jang H-J, Lee YH, Lee E, Hyun J-M, Eom H-J, Yoon S, Choi J-W, Park T-E, et al. PPM1A Controls Diabetic Gene Programming through Directly Dephosphorylating PPARγ at Ser273. Cells. 2020; 9(2):343. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9020343

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhim, Keon Woo, Sun Sil Choi, Hyun-Jun Jang, Yo Han Lee, Eujin Lee, Ji-Min Hyun, Hye-Jin Eom, Sora Yoon, Jeong-Won Choi, Tae-Eun Park, and et al. 2020. "PPM1A Controls Diabetic Gene Programming through Directly Dephosphorylating PPARγ at Ser273" Cells 9, no. 2: 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9020343