Candidalysin Is a Potent Trigger of Alarmin and Antimicrobial Peptide Release in Epithelial Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

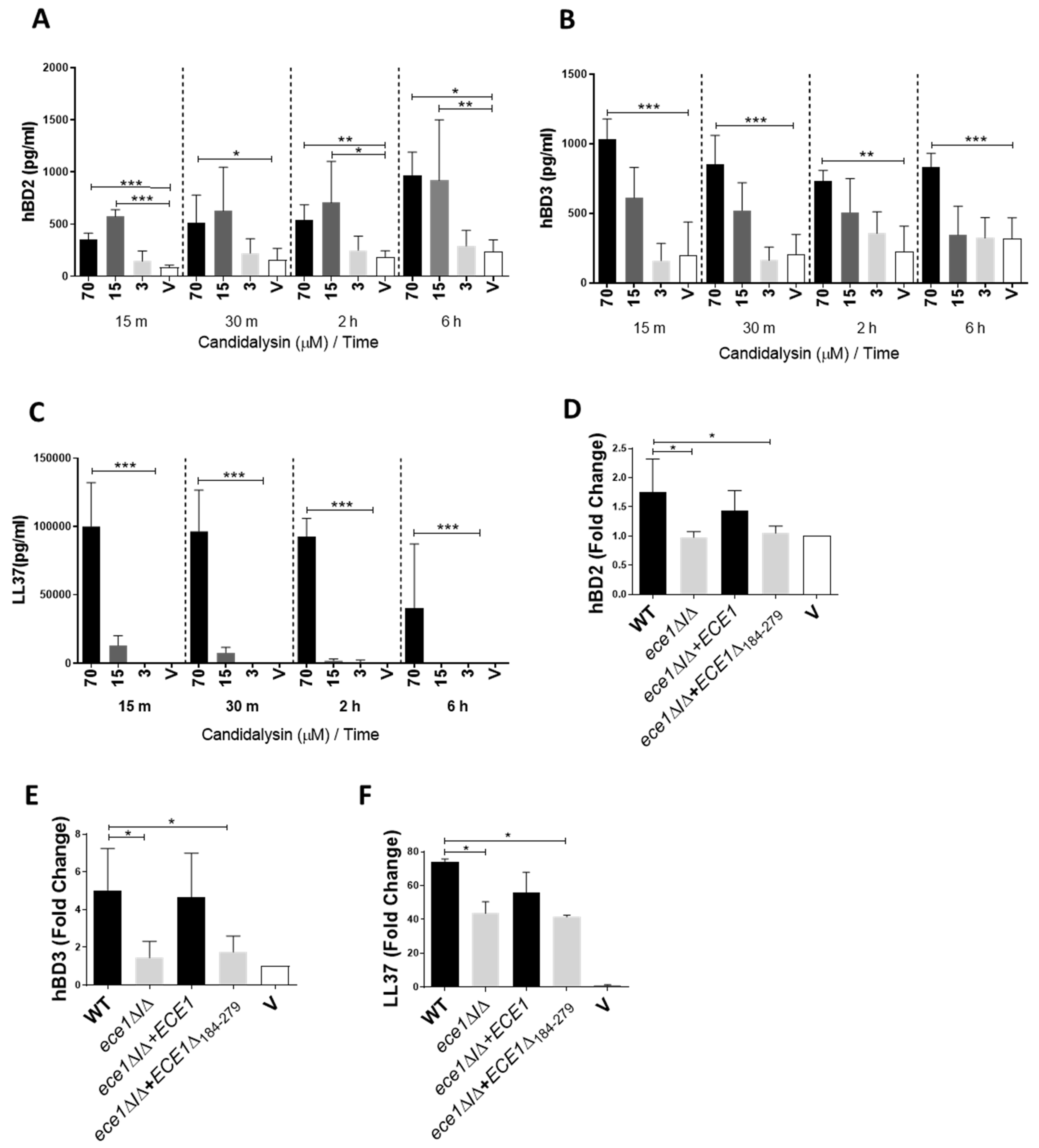

3.1. Candidalysin Induces hBD2, hBD3 and LL37 Release during Oral C. Albicans Infection In Vitro

3.2. Candidalysin Promotes ATP, ROS/RNS and S100A8 Release

3.3. ATP Contributes to Epithelial Cell Activation and Signalling

3.4. Candidalysin-Induced Responses Are Specific and Not a Consequence of General Pore Formation

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Janus, M.M.; Willems, H.M.E.; Krom, B.P. Candida albicans in Multispecies Oral Communities; A Keystone Commensal? Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 931, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Allert, S.; Förster, T.M.; Svensson, C.-M.; Richardson, J.; Pawlik, T.; Hebecker, B.; Rudolphi, S.; Juraschitz, M.; Schaller, M. Candida albicans-Induced Epithelial Damage Mediates Translocation through Intestinal Barriers. MBio 2018, 9, e00915–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.Y. Murine models of Candida gastrointestinal colonization and dissemination. Eukaryot. Cell 2013, 12, 1416–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, S.M.; Gianetti, B.A.; Witchley, J.N. Candida albicans cell-type switching and functional plasticity in the mammalian host. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyes, D.L.; Wilson, D.; Richardson, J.P.; Mogavero, S.; Tang, S.X.; Wernecke, J.; Höfs, S.; Gratacap, R.L.; Robbins, J.; Runglall, M.; et al. Candidalysin is a fungal peptide toxin critical for mucosal infection. Nature 2016, 532, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naglik, J.R.; Gaffen, S.L.; Hube, B. Candidalysin: Discovery and function in Candida albicans infections. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 52, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikou, S.A.; Kichik, N.; Brown, R.; Ponde, N.O.; Ho, J.; Naglik, J.R.; Richardson, J.P. Candida albicans interactions with mucosal surfaces during health and disease. Pathogens 2019, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.P.; Moyes, D.L.; Ho, J.; Naglik, J.R. Candida innate immunity at the mucosa. Seminars Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 89, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.P.; Ho, J.; Naglik, J.R. Candida-Epithelial Interactions. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naglik, J.R.; König, A.; Hube, B.; Gaffen, S.L. Candida albicans-epithelial interactions and induction of mucosal innate immunity. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017, 40, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.; Naglik, J.R.; Hube, B. The Missing Link between Candida albicans Hyphal Morphogenesis and Host Cell Damage. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, J.; Yang, X.; Nikou, S.-A.; Kichik, N.; Donkin, A.; Ponde, N.O.; Richardson, J.P.; Gratacap, R.L.; Archambault, L.S.; Zwirner, C.P.; et al. Candidalysin activates innate epithelial immune responses via epidermal growth factor receptor. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, J.; Moyes, D.L.; Tavassoli, M.; Naglik, J.R. The Role of ErbB Receptors in Infection. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyes, D.L.; Runglall, M.; Murciano, C.; Shen, C.; Nayar, D.; Thavaraj, S.; Kohli, A.; Islam, A.; Mora-Montes, H.; Naglik, J.R.; et al. A biphasic innate immune MAPK response discriminates between the yeast and hyphal forms of Candida albicans in epithelial cells. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 8, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyes, D.L.; Murciano, C.; Runglall, M.; Islam, A.; Thavaraj, S.; Naglik, J.R. Candida albicans Yeast and Hyphae are Discriminated by MAPK Signaling in Vaginal Epithelial Cells. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murciano, C.; Moyes, D.L.; Runglall, M.; Islam, A.; Mille, C.; Fradin, C.; Poulain, D.; Gow, N.A.; Naglik, J.R. Candida albicans cell wall glycosylation may be indirectly required for activation of epithelial cell proinflammatory responses. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 4902–4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyes, D.L.; Murciano, C.; Runglall, M.; Kohli, A.; Islam, A.; Naglik, J.R. Activation of MAPK/c-Fos induced responses in oral epithelial cells is specific to Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis hyphae. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2012, 201, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyes, D.L.; Shen, C.; Murciano, C.; Runglall, M.; Richardson, J.P.; Arno, M.; Aldecoa-Otalora, E.; Naglik, J.R. Protection Against Epithelial Damage During Candida albicans Infection Is Mediated by PI3K/Akt and Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Signaling. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 209, 1816–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.P.; Mogavero, S.; Moyes, D.L.; Blagojevic, M.; Krüger, T.; Verma, A.H.; Coleman, B.M.; De La Cruz Diaz, J.; Schulz, D.; Ponde, N.O.; et al. Processing of Candida albicans Ece1p Is Critical for Candidalysin Maturation and Fungal Virulence. MBio 2018, 9, e02178-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.H.; Zafar, H.; Ponde, N.O.; Hepworth, O.W.; Sihra, D.; Aggor, F.E.Y.; Ainscough, J.S.; Ho, J.; Richardson, J.P.; Coleman, B.M.; et al. IL-36 and IL-1/IL-17 Drive Immunity to Oral Candidiasis via Parallel Mechanisms. J. Immunol. 2018, 201, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.H.; Richardson, J.P.; Zhou, C.; Coleman, B.M.; Moyes, D.L.; Ho, J.; Huppler, A.R.; Ramani, K.; McGeachy, M.J.; Mufazalov, I.A.; et al. Oral epithelial cells orchestrate innate type 17 responses to Candida albicans through the virulence factor candidalysin. Sci. Immunol. 2017, 2, eaam8834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swidergall, M.; Khalaji, M.; Solis, N.V.; Moyes, D.L.; Drummond, R.A.; Hube, B.; Lionakis, M.S.; Murdoch, C.; Filler, S.G.; Naglik, J.R. Candidalysin Is Required for Neutrophil Recruitment and Virulence During Systemic Candida albicans Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 220, 1477–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond, R.A.; Swamydas, M.; Oikonomou, V.; Zhai, B.; Dambuza, I.M.; Schaefer, B.C.; Bohrer, A.C.; Mayer-Barber, K.D.; Lira, S.A.; Iwakura, Y.; et al. CARD9+ microglia promote antifungal immunity via IL-1β- and CXCL1-mediated neutrophil recruitment. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, J.P.; Willems, H.M.E.; Moyes, D.L.; Shoaie, S.; Barker, K.S.; Tan, S.L.; Palmer, G.E.; Hube, B.; Naglik, J.R.; Peters, B.M.; et al. Candidalysin Drives Epithelial Signaling, Neutrophil Recruitment, and Immunopathology at the Vaginal Mucosa. Infect. Immun. 2017, 86, e00645-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidel, P.L.; Barousse, M.; Espinosa, T.; Ficarra, M.; Sturtevant, J.; Martin, D.H.; Quayle, A.J.; Dunlap, K. An intravaginal live Candida challenge in humans leads to new hypotheses for the immunopathogenesis of vulvovaginal candidiasis. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 2939–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swidergall, M.; Ernst, J.F. Interplay between Candida albicans and the Antimicrobial Peptide Armory. Eukaryot Cell 2014, 13, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lorenzo, G.; Ferrari, S.; Cervone, F.; Okun, E. Extracellular DAMPs in Plants and Mammals: Immunity, Tissue Damage and Repair. Trends Immunol. 2018, 39, 937–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Hooper, L.V. Antimicrobial Defense of the Intestine. Immunity 2015, 42, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, J.; Palmer, G.E.; Eberle, K.E.; Peters, B.M.; Vogl, T.; McKenzie, A.N.; Fidel, P.L., Jr. Vaginal Epithelial Cell-Derived S100 Alarmins Induced by Candida albicans via Pattern Recognition Receptor Interactions Are Sufficient but Not Necessary for the Acute Neutrophil Response during Experimental Vaginal Candidiasis. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, J.; Lilly, E.; Barousse, M.; Fidel, P.L. Epithelial Cell-Derived S100 Calcium-Binding Proteins as Key Mediators in the Hallmark Acute Neutrophil Response during Candida Vaginitis. Infect. Immun. 2010, 78, 5126–5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, H.R.; Bruno, V.M.; Childs, E.E.; Daugherty, S.; Hunter, J.P.; Mengesha, B.G.; Saevig, D.L.; Hendricks, M.R.; Coleman, B.M.; Brane, L.; et al. IL-17 Receptor Signaling in Oral Epithelial Cells Is Critical for Protection against Oropharyngeal Candidiasis. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiehne, K.; Brunke, G.; Meyer, D.; Harder, J.; Herzig, K.H. Oesophageal defensin expression during Candida infection and reflux disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 40, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casaroto, A.R.; da Silva, R.A.; Salmeron, S.; Rezende, M.L.R.; Dionísio, T.J.; Santos, C.F.D.; Pinke, K.H.; Klingbeil, M.F.G.; Salomão, P.A.; Lopes, M.M.R.; et al. Candida albicans-Cell Interactions Activate Innate Immune Defense in Human Palate Epithelial Primary Cells via Nitric Oxide (NO) and β-Defensin 2 (hBD-2). Cells 2019, 8, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gácser, A.; Tiszlavicz, Z.; Németh, T.; Seprényi, G.; Mándi, Y. Induction of human defensins by intestinal Caco-2 cells after interactions with opportunistic Candida species. Microbes. Infect. 2014, 16, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Järvå, M.; Phan, T.K.; Lay, F.T.; Caria, S.; Kvansakul, M.; Hulett, M.D. Human β-defensin 2 kills Candida albicans through phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate-mediated membrane permeabilization. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaat0979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupniak, H.; Rowlatt, C.; Lane, E.; Steele, J.G.; Trejdosiewicz, L.K.; Laskiewicz, B.; Povey, S.; Hill, B.T. Characteristics of four new human cell lines derived from squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1985, 75, 621–635. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, F.L.; Wilson, D.; Jacobsen, I.D.; Miramón, P.; Große, K.; Hube, B. The Novel Candida albicans Transporter Dur31 Is a Multi-Stage Pathogenicity Factor. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshlukova, S.E.; Lloyd, T.L.; Araujo, M.W.B.; Edgerton, M. Salivary histatin 5 induces non-lytic release of ATP from Candida albicans leading to cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 18872–18879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, D.G. Melittin triggers apoptosis in Candida albicans through the reactive oxygen species-mediated mitochondria/caspase-dependent pathway. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014, 355, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sham, D.; Wesley, U.V.; Hristova, M.; van der Vliet, A. ATP-Mediated Transactivation of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor in Airway Epithelial Cells Involves DUOX1-Dependent Oxidation of Src and ADAM17. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, I.; Petersen, R.M.; Thompson, E.W.; Roberts-Thomson, S.J.; Monteith, G.R. Hypoxia-induced reactive oxygen species mediate N-cadherin and SERPINE1 expression, EGFR signalling and motility in MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Chen, L.; Bai, L.; Xia, Y.; Yang, X.; Jiang, W.; Sun, W. Reactive oxygen species mediates 50-Hz magnetic field-induced EGF receptor clustering via acid sphingomyelinase activation. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2018, 94, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Cui, A.; Song, P.; Hua, H.; Luo, T.; Jiang, Y. Reactive oxygen species-mediated activation of the Src-epidermal growth factor receptor-Akt signaling cascade prevents bortezomib-induced apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 712–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Chen, Q.; Tang, R.; Shen, Y.; Liu, W.D. The expression of β-defensin-2, 3 and LL-37 induced by Candida albicans phospholipomannan in human keratinocytes. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2011, 61, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonfim-Mendonça P de, S.; Ratti, B.A.; Godoy J da, S.R.; Negri, M.; Lima, N.C.; Fiorini, A.; Hatanaka, E.; Consolaro, M.E.; de Oliveira Silva, S.; Svidzinski, T.I. β-Glucan Induces Reactive Oxygen Species Production in Human Neutrophils to Improve the Killing of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata Isolates from Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Lee, D.G. Role of calcium in reactive oxygen species-induced apoptosis in Candida albicans: An antifungal mechanism of antimicrobial peptide, PMAP-23. Free Radic. Res. 2019, 53, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, P.W.; Cheng, Y.L.; Hsieh, W.P.; Lan, C.Y. Responses of Candida albicans to the human antimicrobial peptide LL-37. J. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.W.; Yang, C.Y.; Chang, H.T.; Lan, C.Y. Human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 inhibits adhesion of Candida albicans by interacting with yeast cell-wall carbohydrates. PLoS ONE 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, S.; Edgerton, M. How does it kill?: Understanding the candidacidal mechanism of salivary histatin 5. Eukaryot. Cell 2014, 13, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, A.D.S.; Day, A.; Ikeh, M.; Kos, I.; Achan, B.; Quinn, J. Oxidative stress responses in the human fungal pathogen, Candida albicans. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 142–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ho, J.; Wickramasinghe, D.N.; Nikou, S.-A.; Hube, B.; Richardson, J.P.; Naglik, J.R. Candidalysin Is a Potent Trigger of Alarmin and Antimicrobial Peptide Release in Epithelial Cells. Cells 2020, 9, 699. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9030699

Ho J, Wickramasinghe DN, Nikou S-A, Hube B, Richardson JP, Naglik JR. Candidalysin Is a Potent Trigger of Alarmin and Antimicrobial Peptide Release in Epithelial Cells. Cells. 2020; 9(3):699. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9030699

Chicago/Turabian StyleHo, Jemima, Don N. Wickramasinghe, Spyridoula-Angeliki Nikou, Bernhard Hube, Jonathan P. Richardson, and Julian R. Naglik. 2020. "Candidalysin Is a Potent Trigger of Alarmin and Antimicrobial Peptide Release in Epithelial Cells" Cells 9, no. 3: 699. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9030699

APA StyleHo, J., Wickramasinghe, D. N., Nikou, S.-A., Hube, B., Richardson, J. P., & Naglik, J. R. (2020). Candidalysin Is a Potent Trigger of Alarmin and Antimicrobial Peptide Release in Epithelial Cells. Cells, 9(3), 699. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9030699