Proanthocyanidins Limit Adipose Accrual Induced by a Cafeteria Diet, Several Weeks after the End of the Treatment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Proanthocyanidin Extract

2.2. Animal Treatments

2.2.1. Short Cafeteria (SC) Experiment

2.2.2. Long Cafeteria (LC) Experiment

2.3. Blood and Tissue Collection

2.4. Plasma Metabolites and Hormones

2.5. Tissue Triglycerides and mRNA Quantification

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

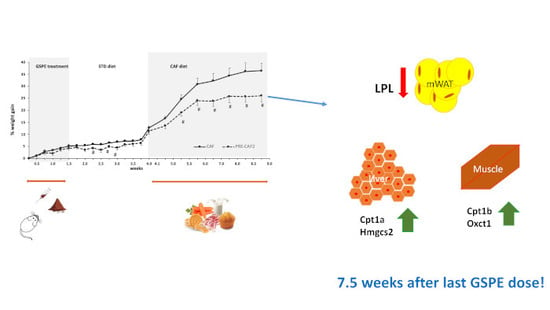

3.1. Sub-Chronic Treatment with GSPE Reduces Food Intake in Rats on a Palatable Diet

3.2. A Reduction in the Expression of Adipose Lpl might Explain the Lower Amount of Adipose Tissue in GSPE Pre-Treated Rats

3.3. Lipid Oxidation in Liver and Muscle Is Higher

3.4. Hormonal Status of GSPE-Treated Rats after the Short-Cafeteria Study

3.5. Duration of GSPE Effects

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization WHO. Obesity and overweight. World Health Organ. Media Cent. Fact Sheet No. 311. 2015. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/ (accessed on 14 August 2019).

- Williams, E.P.; Mesidor, M.; Winters, K.; Dubbert, P.M.; Wyatt, S.B. Overweight and Obesity: Prevalence, Consequences, and Causes of a Growing Public Health Problem. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2015, 4, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvadó, M.J.; Casanova, E.; Fernández-Iglesias, A.; Arola, L.; Bladé, C. Roles of proanthocyanidin rich extracts in obesity. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 1053–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lamothe, S.; Azimy, N.; Bazinet, L.; Couillard, C.; Britten, M. Interaction of green tea polyphenols with dairy matrices in a simulated gastrointestinal environment. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 2621–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada, H.; Del Bas, J.M.; Pajuelo, D.; Díaz, S.; Fernandez-Larrea, J.; Pinent, M.; Arola, L.; Salvadó, M.J.; Bladé, C. Grape seed proanthocyanidins correct dyslipidemia associated with a high-fat diet in rats and repress genes controlling lipogenesis and VLDL assembling in liver. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Casanova, E.; Baselga-Escudero, L.; Ribas-Latre, A.; Cedó, L.; Arola-Arnal, A.; Pinent, M.; Bladé, C.; Arola, L.; Salvadó, M.J. Chronic intake of proanthocyanidins and docosahexaenoic acid improves skeletal muscle oxidative capacity in diet-obese rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, J.; Casanova-Martí, À.; Gual, A.; Pérez-Vendrell, A.M.; Blay, M.T.; Terra, X.; Ardévol, A.; Pinent, M.; Casanova-Martí, À.; Gual, A.; et al. A specific dose of grape seed-derived proanthocyanidins to inhibit body weight gain limits food intake and increases energy expenditure in rats. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 56, 1629–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, J.; Casanova-Martí, À.; Depoortere, I.; Blay, M.T.; Terra, X.; Pinent, M.; Ardévol, A. Subchronic treatment with grape-seed phenolics inhibits ghrelin production despite a short-term stimulation of ghrelin secretion produced by bitter-sensing flavanols. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 2554–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Cardoso, K.; Ginés, I.; Pinent, M.; Ardévol, A.; Arola, L.; Blay, M.; Terra, X. Chronic supplementation with dietary proanthocyanidins protects from diet-induced intestinal alterations in obese rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1601039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bladé, C.; Aragonès, G.; Arola-Arnal, A.; Muguerza, B.B.; Bravo, F.I.; Salvadó, M.J.; Arola, L.; Suárez, M.; Blade, C.; Aragones, G.; et al. Proanthocyanidins in health and disease. Biofactors 2016, 42, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Puiggros, F.; Llópiz, N.; Ardévol, A.; Bladé, C.; Arola, L.; Salvadó, M.J.J.; Puiggròs, F.; Llópiz, N.; Ardévol, A.; Bladé, C.; et al. Grape Seed Procyanidins Prevent Oxidative Injury by Modulating the Expression of Antioxidant Enzyme Systems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 6080–6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Abuin, N.; Pinent, M.; Casanova-Marti, A.; Arola, L.; Blay, M.; Ardevol, A. Procyanidins and their healthy protective effects against type 2 diabetes. Curr. Med. Chem. 2015, 22, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terra, X.; Montagut, G.; Bustos, M.; Llopiz, N.; Ardèvol, A.; Bladé, C.; Fernández-Larrea, J.; Pujadas, G.; Salvadó, J.; Arola, L.; et al. Grape-seed procyanidins prevent low-grade inflammation by modulating cytokine expression in rats fed a high-fat diet. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2009, 20, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castell-Auvi, A.; Cedo, L.; Pallares, V.; Blay, M.; Pinent, M.; Ardevol, A.; Castell-Auví, A.; Cedó, L.; Pallarès, V.; Blay, M.; et al. Grape seed procyanidins improve β-cell functionality under lipotoxic conditions due to their lipid-lowering effect. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Abuin, N.; Martinez-Micaelo, N.; Blay, M.; Ardevol, A.; Pinent, M. Grape-seed procyanidins prevent the cafeteria diet-induced decrease of glucagon-like peptide-1 production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 1066–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crescenti, A.; Del Bas, J.M.; Arola-Arnal, A.; Oms-Oliu, G.; Arola, L.L.; Caimari, A. Grape seed procyanidins administered at physiological doses to rats during pregnancy and lactation promote lipid oxidation and up-regulate AMPK in the muscle of male offspring in adulthood. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginés, I.; Gil-Cardoso, K.; Serrano, J.; Casanova-Martí, À.; Blay, M.; Pinent, M.; Ardévol, A.; Terra, X.; Gin, I.; Gil-Cardoso, K.; et al. Effects of an Intermittent Grape-Seed Proanthocyanidin (GSPE) Treatment on a Cafeteria Diet Obesogenic Challenge in Rats. Nutrients 2018, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalef, M.; Pons, Z.; Iglesias-Carres, L.; Arola, L.; Muguerza, B.; Arola-Arnal, A. Gender-related similarities and differences in the body distribution of grape seed flavanols in rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.; Priego, T.; Palou, M.; Tobaruela, A.; Palou, A.; Picó, C.; Sa, J.; Priego, T.; Palou, M.; Tobaruela, A.; et al. Oral Supplementation with Physiological Doses of Leptin During Lactation in Rats Improves Insulin Sensitivity and Affects Food Preferences Later in Life. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampey, B.P.; Vanhoose, A.M.; Winfield, H.M.; Freemerman, A.J.; Muehlbauer, M.J.; Fueger, P.T.; Newgard, C.B.; Makowski, L. Cafeteria Diet Is a Robust Model of Human Metabolic Syndrome With Liver and Adipose Inflammation: Comparison to High-Fat Diet. Obesity 2011, 19, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.; Casanova-Martí, À.; Gil-Cardoso, K.; Blay, M.T.; Terra, X.; Pinent, M.; Ardévol, A. Acutely administered grape-seed proanthocyanidin extract acts as a satiating agent. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castell-Auvi, A.; Cedo, L.; Pallares, V.; Blay, M.; Ardevol, A.; Pinent, M. The effects of a cafeteria diet on insulin production and clearance in rats. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova-Martí, À.; Serrano, J.; Portune, K.J.; Sanz, Y.; Blay, M.T.; Terra, X.; Ardévol, A.; Pinent, M. Grape seed proanthocyanidins influence gut microbiota and enteroendocrine secretions in female rat. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 1672–1682. [Google Scholar]

- Del Bas, J.M.M.; Fernández-larrea, J.; Blay, M.; Ardèvol, A.; Salvadó, M.J.; Arola, L.; Bladé, C.; Fernandez-Larrea, J.; Blay, M.; Ardevol, A.; et al. Grape seed procyanidins improve atherosclerotic risk index and induce liver CYP7A1 and SHP expression in healthy rats. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 479–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, S.K.; Russell, C.D.; Grauso, N.L.; Brolin, R.E. Omental Adipose. Insulin 1993, 92, 2191–2198. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock, P.H.; Bisgaier, C.L.; Aalto-Set„l„, K.; Radner, H.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Levak-Frank, S.; Essenburg, A.D.; Zechner, R.; Breslow, J.L. Severe hypertriglyceridemia, reduced high density lipoprotein, and neonatal death in lipoprotein lipase knockout mice. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 96, 2555–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Bas, J.M.J.M.; Ricketts, M.L.M.L.; Baiges, I.; Quesada, H.; Ardevol, A.; Salvado, M.J.; Pujadas, G.; Blay, M.; Arola, L.; Blade, C.; et al. Dietary procyanidins lower triglyceride levels signaling through the nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008, 52, 1172–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga-Escudero, L.; Arola-Arnal, A.; Pascual-Serrano, A.; Ribas-Latre, A.; Casanova, E.; Salvadó, M.-J.J.; Arola, L.; Blade, C. Chronic Administration of Proanthocyanidins or Docosahexaenoic Acid Reversess the Increase of miR-33a and miR-122 in Dyslipidemic Obese Rats. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.I.; Chung, M.; Hwang, J.S.; Han, M.; Goo, T.W.; Yun, E.Y. Allomyrina dichotoma (Arthropoda: Insecta) Larvae Confer Resistance to Obesity in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. Nutrients 2015, 7, 1978–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.X.; Han, T.T.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Hu, Y.M. Insulin resistance caused by lipotoxicity is related to oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress in LPL gene knockout heterozygous mice. Atherosclerosis 2015, 239, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardévol, A.; Motilva, M.J.J.; Serra, A.; Blay, M.; Pinent, M.; Ardevol, A.; Motilva, M.J.J.; Serra, A.; Blay, M.; Pinent, M.; et al. Procyanidins target mesenteric adipose tissue in Wistar lean rats and subcutaneous adipose tissue in Zucker obese rat. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalef, M.; Pons, Z.; Bravo, F.I.; Muguerza, B.; Arola-Arnal, A. Tissue distribution of rat flavanol metabolites at different doses. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roland, W.S.U.; Gouka, R.J.; Gruppen, H.; Driesse, M.; Van Buren, L.; Smit, G.; Vincken, J.P. 6-methoxyflavanones as bitter taste receptor blockers for hTAS2R39. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova-Marti, A. Grape seed proanthocyanidins influence gut microbiota and enteroendocrine secretions in rats. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 1672–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margalef, M.; Pons, Z.; Bravo, F.I.; Muguerza, B.; Arola-Arnal, A. Plasma kinetics and microbial biotransformation of grape seed flavanols in rats. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 12, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalef, M.; Pons, Z.; Iglesias-Carres, L.; Bravo, F.I.; Muguerza, B.; Arola-Arnal, A. Lack of Tissue Accumulation of Grape Seed Flavanols after Daily Long-Term Administration in Healthy and Cafeteria-Diet Obese Rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 9996–10003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baselga-Escudero, L.; Pascual-Serrano, A.; Ribas-Latre, A.; Casanova, E.; Salvadó, M.J.; Arola, L.; Arola-Arnal, A.; Bladé, C. Long-term supplementation with a low dose of proanthocyanidins normalized liver miR-33a and miR-122 levels in high-fat diet-induced obese rats. Nutr. Res. 2015, 35, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milenkovic, D.; Deval, C.; Gouranton, E.; Landrier, J.F.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Mazur, A. Modulation of miRNA expression by dietary polyphenols in apoE deficient mice: A new mechanism of the action of polyphenols. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, L.E.; Ferguson, B.S.; Rodriguez, K.; Ricketts, M.L. A grape seed procyanidin extract inhibits HDAC activity leading to increased Pparα phosphorylation and target-gene expression. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bas, J.M.; Crescenti, A.; Arola-Arnal, A.; Oms-Oliu, G.; Arola, L.; Caimari, A. Grape seed procyanidin supplementation to rats fed a high-fat diet during pregnancy and lactation increases the body fat content and modulates the inflammatory response and the adipose tissue metabolism of the male offspring in youth. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castell-Auvi, A.; Cedo, L.; Movassat, J.; Portha, B.; Sanchez-Cabo, F.; Pallares, V.; Blay, M.; Pinent, M.; Ardevol, A.; Castell-Auví, A.; et al. Procyanidins Modulate MicroRNA Expression in Pancreatic Islets. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, R.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.W.; Xu, C.R.; Gradwohl, G.; Tang, X. Differentially expressed microRNA-483 confers distinct functions in pancreatic β -and α-Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 19955–19966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cafeteria | GSPE Pre-Treated Rats | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial treatment: 10 days, tasty diet | ||

| Chow ingested (g) | 8.34 ± 0.4 | 9.10 ± 0.5 |

| Hypercaloric emulsion ingested (g) | 14.01 ± 0.8 | 10.54 ±1.1 * |

| Carbohydrates (Kcal) | 43.04 ± 0.8 | 39.15 ± 0.6 * |

| Lipids (Kcal) | 6.84 ± 0.2 | 5.90 ± 0.2 * |

| Protein (Kcal) | 7.07 ± 0.2 | 7.12 ± 0.2 |

| Final treatment: 35-day cafeteria diet | ||

| Carbohydrates (Kcal) | 43 ± 4.0 | 38 ± 2.0 |

| Lipids (Kcal) | 28 ± 1.0 | 28 ± 0.6 |

| Protein (Kcal) | 8.4 ± 0.3 | 8.0 ± 0.2 |

| Cafeteria | GSPE Pre-Treated Rats | |

|---|---|---|

| Subcutaneous WAT | ||

| Cpt1b | 1.03 ± 0.09 | 1.09 ± 0.12 |

| Lipe | 0.94 ± 0.09 | 0.70 ± 0.05 # |

| Fasn | 1.03 ± 0.09 | 0.74 ± 0.18 |

| Dgat2 | 0.98 ± 0.08 | 0.90 ± 0.08 |

| Cpt1b/Fasn (ratio between them) | 0.93 ± 0.06 | 1.40 ± 0.15 * |

| Periovaric WAT | ||

| Cpt1b | 1.01 ± 0.07 | 1.17 ± 0.05 |

| Retroperitoneal WAT | ||

| Cpt1b | 1.15 ± 0.20 | 1.27 ± 0.29 |

| Fasn | 1.00 ± 0.08 | 0.95 ± 0.12 |

| Dgat2 | 1.00 ± 0.05 | 0.99 ± 0.09 |

| Cpt1b/Fasn (ratio between them) | 1.26 ± 0.24 | 1.56 ± 0.41 |

| Mesenteric WAT | ||

| Cpt1b | 1.05 ± 0.08 | 0.97 ± 0.1 |

| Fasn | 0.95 ± 0.13 | 0.62 ± 0.1 # |

| Dgat2 | 1.01 ± 0.09 | 0.78 ± 0.16 |

| Cpt1b/Fasn (ratio between them) | 1.22 ± 0.27 | 1.50 ± 0.18 |

| Chow Diet | Cafeteria Diet | GSPE Pre-Treated Rats | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cpt1a (A.U.) | 0.34 ± 0.12 * | 1.01 ± 0.08 | 0.35 ± 0.09 * |

| Fasn (A.U.) | 4.24 ± 0.80 * | 0.92 ± 0.18 | 2.69 ± 0.87 # |

| Dgat2 (A.U.) | 1.23 ± 0.10 | 1.04 ± 0.12 | 1.36 ± 0.07 * |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ginés, I.; Gil-Cardoso, K.; Serrano, J.; Casanova-Marti, À.; Lobato, M.; Terra, X.; Blay, M.T.; Ardévol, A.; Pinent, M. Proanthocyanidins Limit Adipose Accrual Induced by a Cafeteria Diet, Several Weeks after the End of the Treatment. Genes 2019, 10, 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10080598

Ginés I, Gil-Cardoso K, Serrano J, Casanova-Marti À, Lobato M, Terra X, Blay MT, Ardévol A, Pinent M. Proanthocyanidins Limit Adipose Accrual Induced by a Cafeteria Diet, Several Weeks after the End of the Treatment. Genes. 2019; 10(8):598. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10080598

Chicago/Turabian StyleGinés, Iris, Katherine Gil-Cardoso, Joan Serrano, Àngela Casanova-Marti, Maria Lobato, Ximena Terra, M Teresa Blay, Anna Ardévol, and Montserrat Pinent. 2019. "Proanthocyanidins Limit Adipose Accrual Induced by a Cafeteria Diet, Several Weeks after the End of the Treatment" Genes 10, no. 8: 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10080598

APA StyleGinés, I., Gil-Cardoso, K., Serrano, J., Casanova-Marti, À., Lobato, M., Terra, X., Blay, M. T., Ardévol, A., & Pinent, M. (2019). Proanthocyanidins Limit Adipose Accrual Induced by a Cafeteria Diet, Several Weeks after the End of the Treatment. Genes, 10(8), 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10080598